By William E. Welsh

Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, was troubled by reports he was receiving in March 1471 that an invasion by King Edward IV was imminent. Warwick had driven his former protégé, the 29-year-old Yorkist king, from the realm six months before, but the earl knew it was only a matter of time before the willful Edward returned to fight for the throne.

Forty-three-year-old Warwick, the most powerful magnate in the English realm, sent mounted messengers galloping to his allies in every corner of the kingdom. The riders delivered messages in which the earl exhorted his allies to redouble their patrols of the coast to ensure that Edward and his foreign army of “Flemings, Easterlings, and Danes,” to use Warwick’s words, should be driven into the sea and not allowed to gain a foothold on English soil. His reference to foreign mercenaries was a ploy to stir up resentment against Edward.

Warwick had deployed his forces carefully against the invasion. A strong Lancastrian fleet patrolled the English Channel, making a landing in the south unlikely, and Lancastrian armies in the North, East Anglia, and the West Country were prepared to contest a landing in those areas. He prayed his lieutenants and captains would be able to crush the invasion at the coast.

People in the towns and on farms throughout England felt that Edward might land at any moment. They imagined a great battle would take place that would determine once and for all whether the House of York or the House of Lancaster was to rule the land. Warwick and Edward, who had once fought side by side in the name of the House of York, were going to do everything in their power to kill each other and put an end to a 16-year civil war that had drenched the countryside in blood and cast a crimson veil over the throne.

The Act of Accord

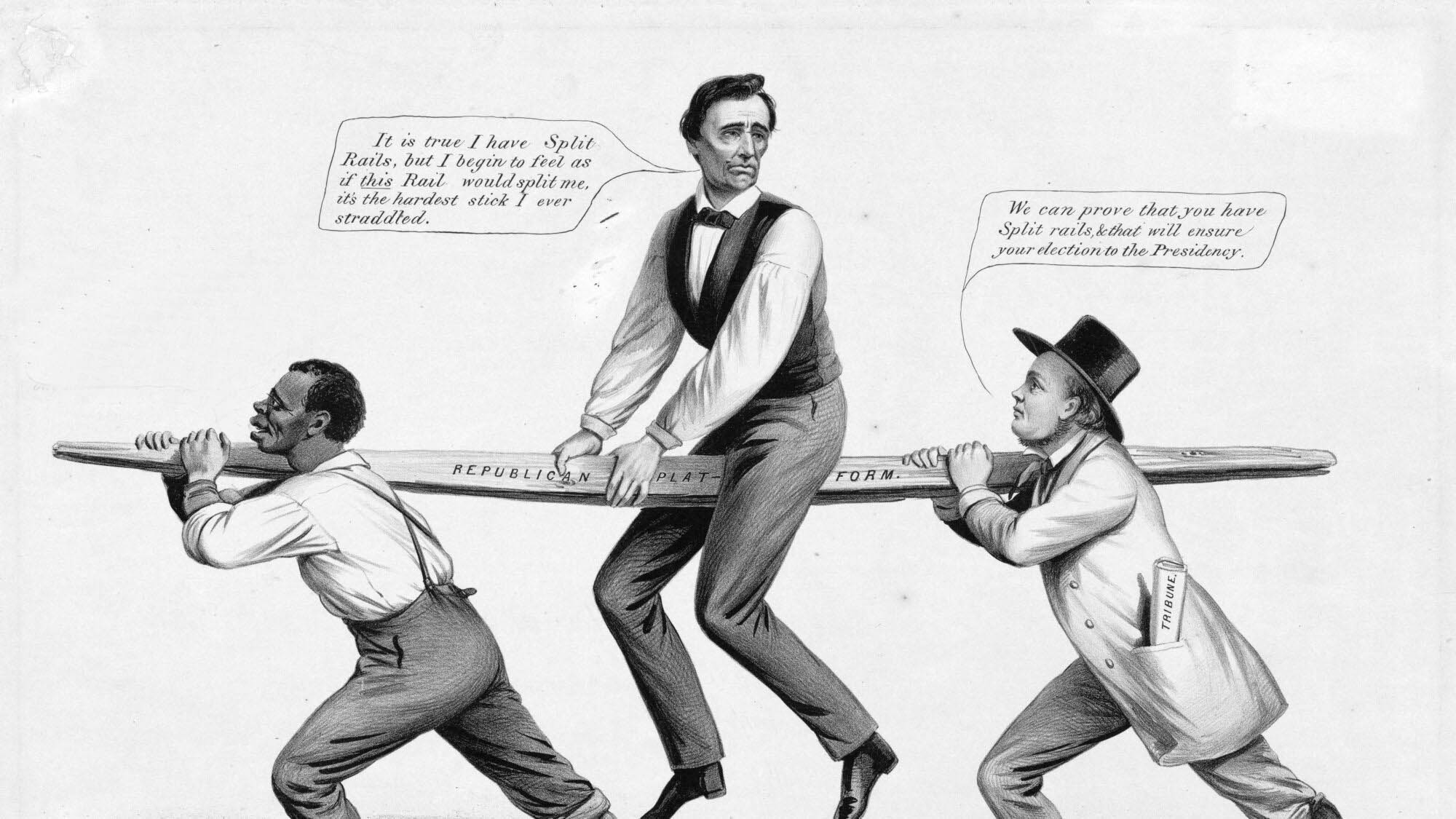

The seeds of England’s civil war, which later generations refer to as the Wars of the Roses, grew out of the discontent of the most powerful peers of the realm with the rule of Lancastrian King Henry VI, whom they blamed for the defeat of English forces in the Hundred Years War with France.

Chief among the critics of Henry VI and his advisers was Richard Plantagenet, Third Duke of York, who in 1450 began pressuring the king to rid himself of his closest councilor, Edmund Beaufort, Second Duke of Somerset, whom York accused of treason for his failings as the leader of English forces in France. York attempted unsuccessfully to seize control of the government on the king’s behalf in 1452, but was unable to get sufficient support from other English peers to prevail. But when the king went mad the following year, York pressed his case to become the protector again, an office he obtained in March 1454. However, Henry VI recovered the following year, which put an end to the First Protectorate.

Initially, blood was shed at the First Battle of St. Albans when York and Warwick broke up a meeting of Henry VI’s court and slew a number of powerful Lancastrian magnates, including Somerset. York took Henry VI prisoner and established the Second Protectorate.

In the fall of 1459, the Lancastrians forced York and his supporters, including Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, and his son, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, to flee the country. By that time, Henry’s wife, Margaret of Anjou, had become his chief adviser. The following spring, the Yorkists defeated the Lancastrians at the Battle of Northampton. This victory paved the way for York to not only reestablish himself as lord protector but also to arrange through the Act of Accord the disinheritance of Henry’s son, Edward, Prince of Lancaster, and stipulated that York and his heirs were to succeed to the throne on Henry’s death.

Although the act called for the Yorkists to support Henry VI as king until his death, it remained unsatisfactory to the Lancastrian faction. When York marched north the following year to suppress a large Lancastrian army, he and Salisbury were slain at the Battle of Wakefield.

Edward IV Ascends to the Throne

The slain duke’s eldest son, Edward, Fourth Duke of York, quickly took up where his father left off. Despite the Act of Accord’s provision that Henry was to remain on the throne until his death, Warwick had Edward declared king on March 4, 1461, while Henry and Margaret were with the Lancastrian army in northern England. Edward subsequently secured his claim to the throne as the first king of the House of York in a decisive defeat of the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton on March 29.

Edward ruled under the guidance of Warwick, who served as his chief adviser in both domestic and foreign matters. Henry was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London, and Margaret took refuge first in Scotland and later in France.

Edward’s mother, Cecily Neville, gave birth to him in 1442 in Rouen in English-held Normandy. The birth took place during his father’s second term as lord lieutenant in charge of English forces in France. On his 12th birthday in 1454, young Edward received the title, Earl of March. He subsequently gained military experience in the company of his father and cousin, Warwick, during the first major period of warfare between 1459 and 1461.

Because of the confidence Edward had gained during the tumultuous period following his father’s death, it wasn’t long before he felt that as king he was better qualified than his cousin Warwick, who was 14 years older than him, to make decisions on behalf of the realm.

Conflict Between Edward and Warwick

Three years after ascending to the throne, the headstrong young monarch secretly wed Elizabeth Woodville, a widow of the lesser nobility who had appealed to him for assistance after she had been denied the inheritance of her late husband’s estates following his death fighting with the Lancastrians at the Second Battle of St. Albans in 1461. Edward became quite fond of her, and he decided to marry her in 1464 even though it was a well-established tradition for the English king to marry a woman of noble birth from the Continent to gain a diplomatic advantage with another royal family.

The marriage, which Warwick and others learned about after the fact, also had another major repercussion; namely, it gave the large Woodville family access to titles and lands as part of the system of royal patronage that they would not otherwise have gained. The increased influence of the Woodville family in Edward’s royal court meant diminished influence and wealth for Warwick.

The rift between Edward and Warwick became greater as the decade progressed. When Warwick sought to marry his two daughters to Edward’s brothers, Clarence and Richard, to strengthen his ties to the royal family, he was rebuffed. Edward and Warwick also clashed over foreign affairs. Warwick favored an alliance with French King Louis XI, while Edward favored closer ties with the Duke of Burgundy. On this matter, Edward once again did as he felt was in the best interests of the realm by arranging for his younger sister, Margaret of York, to wed Charles, Duke of Burgundy, in 1468.

Edward’s Capture, Lancastrian Rebellion

Not content with his diminished importance in Edward’s court, Warwick plotted with Edward’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence, to unseat Edward the following year. In the spring of 1469, a group of Yorkist rebels in northern England, led by an anonymous knight who called himself Robin of Redesdale, rose up against Edward and demanded in a manifesto that the king rid himself of all advisers other than Warwick and the Neville family. Warwick, who secretly guided the rebellion, was able to recruit Clarence to his cause. When Edward found himself isolated without sufficient military forces to resist Warwick and Clarence, he surrendered himself that summer to George Neville, Archbishop of York, who was one of Warwick’s brothers. After his surrender, Edward became Warwick’s prisoner.

The following months were difficult for Warwick. He had not foreseen that the majority of the English were satisfied with Edward’s rule, which had lasted for nearly a decade, and many peers of the realm refused to cooperate with him. What’s more, a small Lancastrian rebellion broke out in the North, which the earl found difficult to crush without Edward’s support. For these reasons, in the fall of 1469 Warwick and Clarence struck a deal with Edward in which he was freed in exchange for pardoning them. The Lancastrian revolt was crushed, and Edward was restored to the throne.

Flight to Continental Europe

Warwick had no interest in reconciling himself with Edward. Allying himself once more with Clarence, the two magnates lured Edward away from London in March 1470 to stamp out another manufactured rebellion in Lincolnshire led by Warwick crony Sir Robert Welles. This time Warwick intended to dethrone Edward in favor of Clarence, who was now his son-in-law following his marriage to Neville’s eldest daughter, Isabella.

Warwick’s strategy called for trapping Edward’s army between Welles’s force marching south and a force raised by Warwick and Clarence marching from the Midlands. The earl’s strategy quickly unraveled. First, he and Clarence couldn’t raise sufficient men to form an army. Second, Edward learned of Welles’s perfidy and threatened to execute his father unless the son surrendered. Anxious to free his father, Welles prematurely attacked Edward’s army. At the Battle of Losecote Field on March 12, 1470, the king’s army routed Welles’s force. Perhaps disgusted with Warwick’s second betrayal, Edward acted in a more ruthless manner against his opponents. Lord Welles, the father, was executed before the battle, and his captured son, who had led the rebels, was executed after the battle.

Lacking sufficient forces to resist Edward, Warwick, Clarence, and their ally John de Vere, the 13th Earl of Oxford, rode south to Dartmouth and sailed to the Continent. When the English garrison at Calais refused to let them land, they instead went to France. Louis XI, who was anxious to have an ally on the English throne to reduce support for Burgundy, granted asylum to Warwick and Clarence. Still convinced that he was the most qualified to rule, Warwick entered negotiations with Margaret of Anjou for an invasion in which Yorkist King Edward would be removed and replaced with her son, Edward, Prince of Wales.

To bind his family to the Lancastrians, Warwick agreed in the Angers Agreement—an agreement he signed in July with Margaret—to restore Henry VI to the throne. In return, Margaret agreed to wed her 17-year-old son, Edward, Prince of Wales, to Warwick’s younger daughter, Anne. Warwick’s ultimate intention as a kingmaker, despite his vow to put the feeble-minded Henry back on the throne, was to install Prince Edward on the throne. If Prince Edward and Warwick’s daughter had children, then Warwick would be the maternal grandfather of future royal blood.

The terms of the agreement stipulated that Warwick was to invade England, remove Edward from the throne by force, and restore Henry to the throne. Once this was accomplished, Margaret and Edward would return to London, where they would be reunited with Henry VI, who was Edward’s prisoner in the Tower of London.

Edward Flees England

While Warwick was plotting his return, yet another rebellion broke out in northern England, orchestrated by some of his Yorkist supporters. Edward arrived in Yorkshire on August 14 with a small army with the intent of putting down the rebellion.

Meanwhile, Louis furnished Warwick and Clarence with vessels to transport them to England. They departed France on September 9 and landed several days later at Dartmouth. They immediately marched north to rendezvous with the earl’s retainers in the Midlands.

At that point, a crucial event occurred that altered the balance of power among the Yorkists. Warwick’s younger brother, John Neville, Marquis of Montagu, defected to the Lancastrian side to join his older brother in attempting to dethrone Edward.

Montagu previously had been Earl of Northumberland. The earldom, which traditionally had resided with the rival Percy family, had been given by Edward to John Neville in 1464 in recognition for his service repelling Lancastrian forays from Scotland following Edward’s ascension to the throne. Following Warwick’s betrayal, in March 1470 Edward returned the earldom to Henry Percy, whose father had been slain fighting for the Lancastrians at Towton. To compensate John Neville for his loss of the earldom, Edward gave him the title Marquis of Montagu, which, unlike the earldom, did not come with any estates. Edward’s move was done to reduce the power of the Neville family in the North.

Torn between his loyalty to both Edward and his older brother, Montagu took an army of 6,000 that Edward had raised and led it against his former benefactor. This left Edward to face him with only 2,000 men. Realizing that Warwick had substantially larger forces than he could raise, Edward fled south to King’s Lynn in Norfolk, which was under the control of his ally, Anthony Woodville, the Earl of Rivers. With most of England under the control of either the Lancastrians or Yorkists loyal to Warwick, the king had no other option than to leave the country. Edward was able to arrange for three ships to transport his small force to Holland. On October 2, the ships set sail. Accompanying Edward on the voyage were Rivers, Lord William Hastings, and Edward’s youngest brother, Richard Plantaganet, Duke of Gloucester.

The Readeption of Henry VI

On October 5, Archbishop Neville entered London with a sizable force and secured control of the tower in preparation for the arrival of Warwick and Clarence. The following day the earl and duke arrived in the city to take control of the government. Keeping his promise to Margaret, Warwick promptly released Henry VI from the tower and restored him to the throne. The event became known as the Readeption of Henry VI.

Warwick made as few changes as possible in the lower echelons of Edward’s government to maintain popular support for the new Neville-directed throne of England. For the most part, the individuals who had been serving in judicial and law enforcement functions were reappointed. As negotiated in the Angers Agreement, Warwick became the king’s lieutenant of the realm. To increase his ability to control the military, Warwick took for himself key positions, such as chamberlain of England, captain of Calais, and lord high admiral.

To maintain a careful balance of power, Warwick did not redistribute Yorkist lands and titles to prominent Lancastrians. He did not give Lancastrian nobles, such as Montagu, Oxford, William Stanley (Lord Stanley), and George Talbot (Earl of Shrewsbury) either a role in the government or a seat on the royal council. To avoid alienating the Lancastrians, he also delayed as long as possible Clarence’s reappointment as lieutenant of Ireland. Even though the Neville-directed throne was short of funds, Warwick paid for many expenses out of his own pocket rather than alienate Parliament by asking it for a large grant.

Edward spent his time in Holland writing to supporters in England and working with those who had accompanied him, such as Rivers, to arrange for the assembly of ships necessary to eventually transport him back to England. Whereas Duke Charles of Burgundy had tried to remain neutral in the dispute between the two English houses, the realization that a Lancastrian England allied with his enemy, Louis XI, compelled him to secretly finance Edward in the belief that Edward, now his brother-in-law, would remain a staunch ally if he was returned to the English throne. To help Edward procure ships and hire a small mercenary force to ensure he gained a foothold on English soil, Charles gave his brother-in-law 50,000 florins. In addition, Edward secured loans from English merchants keen on retaining strong commercial ties with the Burgundian Netherlands.

Edward perceived that his brother, Clarence, was feeling insecure about his position in the Neville-led Lancastrian government. He therefore wrote multiple letters to Clarence, which were delivered by Edward’s sympathizers, imploring him to support a Yorkist invasion. While Edward continued the secret correspondence, his supporters began assembling an invasion fleet at Flushing in February.

Edward’s Return

On March 2, 1471, Edward boarded his flagship. Unfortunately, the fleet could not gain favorable winds for more than a week, which meant that three dozen ships of various sizes had to remain in protected waters ready to sail once the wind turned. Aboard the ships were 1,200 mercenaries, including a contingent of handgunners. On March 11, the fleet sailed into the North Sea bound for East Anglia.

The following evening, Edward’s fleet anchored off the coast of Norfolk. Unsure of the measure of local support he might receive, he sent a small party ashore to ascertain whether circumstances were favorable for landing his entire force. Upon learning that the area was tightly controlled by Warwick’s ally, the Earl of Oxford, the party boarded again, and on March 13 the fleet sailed north in search of a more favorable place to land. That evening a great storm arose that scattered the ships. Rather than try to reassemble the fleet, the various groups landed wherever they were along the coast once the seas were calm enough to allow them to go ashore.

Edward’s force landed the following day in three groups near Ravenspur in East Yorkshire. Initially inclined to immediately march south where he had the most supporters, Edward agreed to follow the advice of his lieutenants that he should establish his presence first in the Lancastrian-controlled North to show that he was confident of success no matter where he landed in England.

March to Sandal Castle

The small Yorkist army struck out for the nearest major town in East Yorkshire, which was Hull. The Yorkists had predicted correctly that they were generally unwelcome in the North even though Edward’s father had held the title of Duke of York. When Edward’s army reached Hull, it was denied entry. The countryside was full of Lancastrian levies, but they lacked a leader to organize them to resist Edward’s invasion.

Edward continued east, and on March 18 his army arrived at York, which was located in North Yorkshire. In a meeting with Lancastrian officials of the town, Edward told them that he had returned only to reclaim his dukedom. Believing the falsehood, the officials allowed Edward and his brother to enter with a small escort. By denying entry to his army, they sought to prevent Edward from occupying the walled town and using it as a base.

The following day, Edward led his army on a southwest course to Sandal Castle, the site of his father’s defeat by a large Lancastrian army in December 1460. There he was reinforced on March 20 by a small number of troops loyal to him in the North. He was aware that Montagu was at Pontefract Castle a short distance to the east. For reasons unknown to Edward, Montagu did not pursue or attempt to block Edward’s attempt to reach Sandal Castle.

Still wary that Montagu might attack his column, Edward pushed it hard on its march to Nottingham in the Midlands. With scouts guarding its flanks, the Yorkist army tramped southeast to Doncaster and then south for Nottingham. Warwick was sorely disappointed to learn that his brother had not attacked the Yorkists before they left the North.

The most likely reason that Montagu failed to attack Edward was that he was reluctant to strike Edward by himself. He probably preferred that his brother be the one to lead an army in battle against Edward.

Edward and the Lancastrians Assemble Their Armies

Montagu’s northern army was not the only Lancastrian army that was mobilizing against Edward. Upon learning that Edward had landed, Oxford had sent letters to his supporters instructing them to assemble at King’s Lynn in Norfolk for a march to intercept Edward’s army. While Edward was on his way to Nottingham, Oxford arrived in King’s Lynn and made a quick inspection of his army. On March 22, Oxford led his force west. His destination was Newark-on-Trent, which lay a day’s march from Nottingham.

At Newark, Oxford was joined by large contingents led by two other Lancastrian nobles. One was Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, a staunch Lancastrian who had fled abroad following Towton and returned to England to support the readeption. The other was Lord William Beaumont, who had lost his estates when Edward transferred them to Hastings following the Yorkist victory at Towton. Despite the loss of their estates, these men still had hundreds of loyal followers. Altogether, the Lancastrian army at Newark numbered 4,000 men.

At Doncaster, Edward was joined by a pair of Yorkist knights who brought 600 men with them and news that more were on the way from Lancashire. Arriving in Nottingham on March 24, Edward learned from his scouts that a substantial Lancastrian force under Oxford was located at Newark. The following day, Edward’s army tramped north to attack the Lancastrians. Even though he was outnumbered, Edward hoped that he could surprise and rout Oxford’s army.

But the clash never occurred. Oxford ordered his entire force to withdraw under cover of night. Like Montagu, he most likely was reluctant to fight Edward until he had united with Warwick.

When the Yorkist king learned that Oxford’s army had withdrawn, Edward countermarched south to Leicester, where he received 3,000 additional reinforcements from Lancashire. The Lancashire men were loyal to Hastings, who was the recipient of the Lancastrian estates during Edward’s rule.

At the time, Warwick was at Warwick Castle where he was assembling forces from his vast estates in the Midlands. Once he had organized his personal army, he marched to Coventry, which was the second strongest walled town in England after London. While Edward was at Leicester, the other two Lancastrian armies, one led by Montagu and the other by Oxford, marched around Edward and joined Warwick. The combined Lancastrian army in Coventry numbered 15,000.

On March 29, Edward arrived with his 6,000-strong army outside Coventry. He had his army deploy for battle on the outskirts of the city. This was a customary invitation to battle. But Warwick refused even though his army was more than twice the size of Edward’s. The earl had received a letter from Clarence advising him to await his arrival with reinforcements before accepting Edward’s invitation to battle. What’s more, Warwick respected Edward’s qualities as a military leader, and he knew that the opposing army had a block of professional soldiers from the Continent.

Edward Aims For London

Located in the heart of the Midlands, the important commercial center of Coventry was an intimidating stronghold. Work on the city’s 31/2-kilometer circuit of eight-foot-thick red sandstone walls had begun in 1350 and taken a half century to complete. The walls bristled with 32 guard towers. Edward’s only hope was that Warwick would march out to meet him. The Yorkist king had neither the weapons nor the time to conduct a lengthy siege of a strongly held town.

Edward also sent word to Warwick that he would grant him a pardon. But Warwick spurned the offer as he had resolved not to serve as one of Edward’s counselors, but rather as the de facto leader under the readeption.

Clarence had been in the West Country raising his own force when Edward landed. About the time Edward arrived before Coventry, Clarence led his 4,000-man army northwest toward the contested Midlands. On April 2, the duke’s army arrived in Burford in Oxfordshire.

Edward had no intention of allowing Clarence to reinforce Warwick. On the same day Clarence reached Burford, Edward quit Coventry and shifted his forces south to Warwick Castle. By capturing Warwick’s primary residence, he hoped to anger the earl into marching to its relief. But the earl was not so easily manipulated. His army remained securely behind Coventry’s thick walls awaiting Clarence’s arrival.

On April 3, Clarence and his personal army arrived in Banbury, which lay a day’s march from Edward’s position at Warwick. That afternoon Edward and Richard met with their brother on the Banbury Road to discuss a possible reconciliation. Clarence was bitter because Warwick had not given him a role in the new Lancastrian government. Furthermore, his mother, Cecily Neville, and his sister had urged him to resolve his differences with Edward upon his brother’s return to England in 1471. Heeding the advice of his family, Clarence reconciled with Edward, and his large group of retainers and levies nearly doubled Edward’s Yorkist army.

On April 4, Clarence rode with his brothers to Coventry. Upon their arrival, Clarence beseeched Warwick to accept Edward’s pardon, but the earl again declined the offer. Having tried their best to solve the dispute by words rather than force of arms, Edward on April 5 marched south toward London where he hoped to recruit more men, as well as capture Henry VI, thus removing him once more as a willing pawn in the game of dynastic chess.

Guarded Only by Militia

Unwittingly, a well-led Lancastrian army that had been in the vicinity of London left the region the same day headed for the West Country. The army, led by Edmund Beaufort, Fourth Duke of Somerset, planned to rendezvous with Queen Margaret, her son, Prince Edward, and a small force of men at arms. Beaufort and his lieutenants, who had been dealt with harshly by Warwick under Edward’s reign, had no desire to overtly assist him. In their minds it was his responsibility to vanquish Edward with his own forces. Their allegiance lay primarily with Henry VI and Margaret. Although Margaret and her troops boarded their vessels at Honfleur on March 24, repeated storms in the Channel kept them bottled up in port for three weeks.

When news reached Warwick of Edward’s destination, he sent a messenger to his brother, Archbishop George, to muster the city’s militia to prevent its capture by Edward. The archbishop called up the militia, but there were no military leaders of note to organize a stout defense against the Yorkist king.

Edward’s march to London was a slow affair. Believing that Warwick might attack his column from behind, the king handpicked some of his best mounted men-at-arms and archers to create a strong rear guard to ensure that his army would not be vulnerable to attack. He also conducted a slow march to allow those who wanted to join his army from the counties through which he marched to have sufficient time to be incorporated into the ranks.

On April 8, Edward’s army, having passed through Northampton the previous day, arrived in Dunstable in Bedfordshire. Edward occupied St. Albans on April 10 after a short march. There the king waited for his Yorkist supporters to do what they could to persuade the militia to allow Edward to enter unopposed. Municipal officials loyal to Edward were able to persuade the troops to go home to dinner that night and await a summons to return to their posts. The officials had no intention of calling them out again. A dispatch was sent to Edward telling him to arrive the following morning.

“I Know in Your Hands My Life Will Not be in Danger”

With the troops still billeted in their homes the morning of April 11, Edward entered London at the head of his army through Bishopsgate. Marching behind Edward in the vanguard were 500 Flemish handgunners who scowled and cast looks about designed to make any dissenters think twice about disrupting the king’s intentions.

A band of Edward’s soldiers accepted the surrender of Archbishop Neville, who had sent a note to the Yorkist king the previous day indicating that he would cooperate with him once he entered London. The archbishop was removed to the Tower of London. Edward later pardoned him.

Meanwhile, Edward sought out Henry VI, who was ensconced at the Bishop’s Palace where he had been under the watch and care of the archbishop. “My cousin of York, you are welcome,” said Henry. “I know in your hands my life will not be in danger.” Henry was correct. Edward ordered the pathetic, dethroned Lancastrian king taken to the tower for safekeeping.

Encamping Near the Enemy

On April 12, which was Good Friday, Edward learned from his scouts that Warwick was marching to London hoping to attack the Yorkist king on Easter Sunday, when it was assumed Edward would be resting his army. But Edward was not a naïve military commander, and he fully appreciated the possibility of Warwick’s launching such an attack.

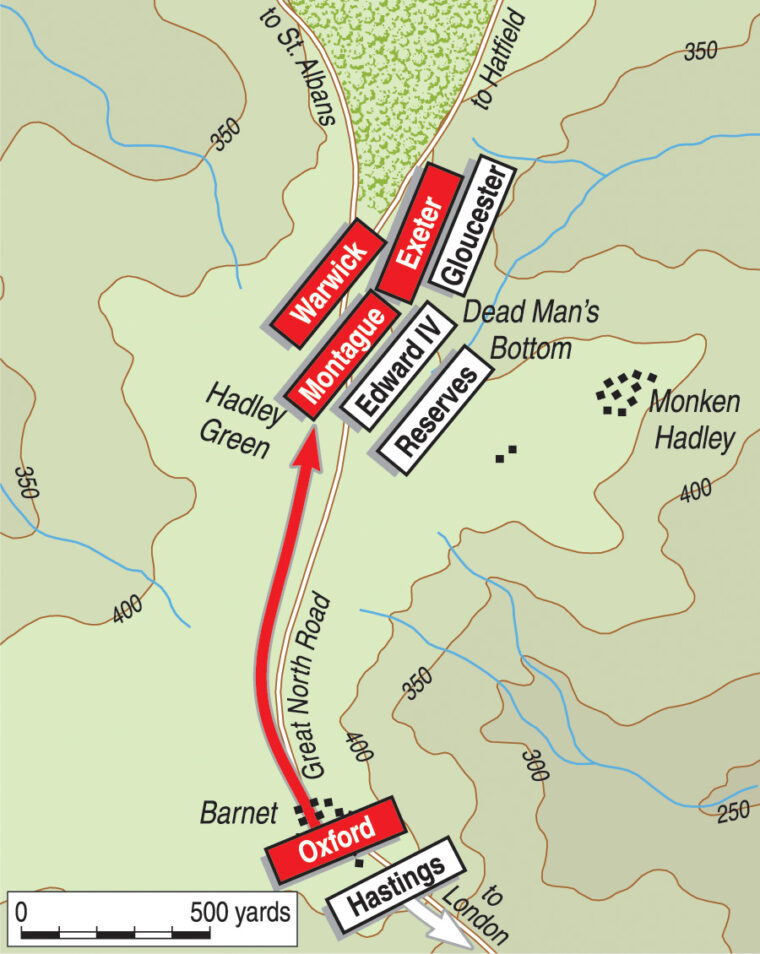

The following day, April 13, Edward’s army marched north on the Great North Road. His scouts skirmished that afternoon with Warwick’s scouts at the village of Barnet, 12 miles north of London. The Yorkist scouts got the better of their Lancastrian counterparts, and when they chased them through the village and beyond, they saw Warwick’s 15,000-strong Lancastrian army assembled on a slight ridge a half mile north of the town. The scouts returned to Edward with news that the enemy host had been located.

Edward marched his army after darkness as quietly as possible to a position a quarter of a mile from Warwick’s army. The decision to camp so close to the enemy, which was done to ensure that the Yorkists would be in position to attack at daylight, had an unexpected benefit.

Warwick, who learned that Edward was encamped just to the south, ordered his gunners to bombard the enemy throughout the night. The stone shells passed harmlessly over the camp. It was a novel use of artillery for the time, as medieval field artillery generally was used only at the beginning of a battle. Edward ordered his gunners not return fire so as not to reveal his exact position.

Warwick accompanied by Oxford, Montagu, and Exeter and their troops. As for Edward, he had his two brothers, Hastings and Rivers, fighting on his side. Other peers who contributed substantial troops to Edward’s army were Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex; John Bourchier, Lord Berners; Humphrey Bourchier, Lord Cromwell; and William Fiennes, Lord Say and Sele. The large number of peers in Edward’s army substantially raised the morale of his troops and instilled them with the belief that they were fighting for a just cause.

A Battle on Foot

Both sides would fight dismounted because the accuracy of the English longbows made it impossible for mounted knights to reach an enemy line before their horses had been stopped by a storm of arrows. An added benefit of having the men-at-arms fight dismounted was that it stiffened the resolve of the green levies in the infantry ranks. Warwick liked to direct the battle from the saddle, but his brother John convinced him that it would hearten the Lancastrian levies to have the earl fight on foot among them.

Since both armies were made up of Englishmen who dressed in a similar manner for battle and carried similar weapons, the retainers and levies of each peer of the realm wore the livery or badge, or both, of their noble. In the case of men-at-arms encased in plate armor, they might wear the livery over their armor, and the levies would do the same over their jackets. At Barnet, Warwick’s men wore red livery and had a badge showing a ragged staff. Edward’s men had livery of blue and red with a badge showing a sun with streamers.

Both armies were divided into three “battles,” of which the closest comparison in modern armies would be the division. Each battle comprised an unspecified number of companies, each of which was led by a captain. Companies ranged from several dozen men to several hundred.

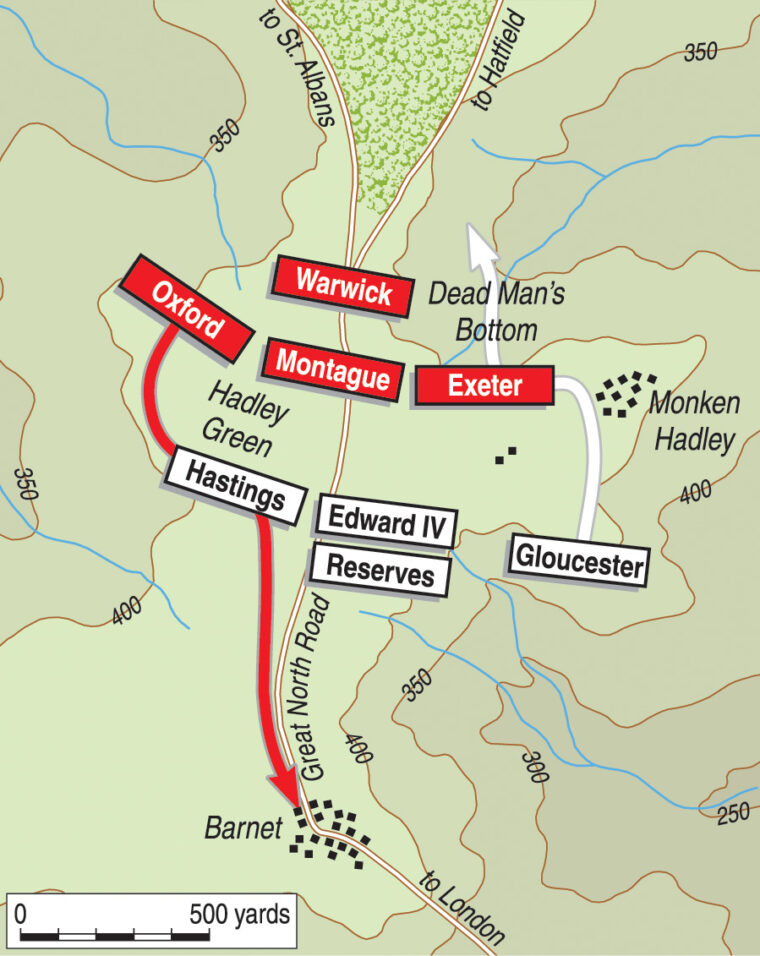

The Battle Lines are Drawn

Warwick’s Lancastrian force had the advantage of the high ground, and nearly half of the army was protected by the lay of the land. The Lancastrian line, which was situated about a half mile north of Barnet, was astride the Great North Road. From right to left the battles were led by Oxford, Montagu, and Exeter. Oxford’s men, who were deployed on the right, enjoyed the advantage of deploying behind a hedgerow, which served as a natural entrenchment. Warwick established a reserve behind Montagu’s battle. The earl then joined his brother in the center of the battlefield.

The hedgerow was one of many in the area that divided the open ground north of Barnet known as Gladsmuir Heath into a large number of separate fields. Behind the Lancastrian line was a small manor house known as Old Fold Manor, which had a moat around it. Beyond the house to the north the Great North Road bent northeast, while another road branched off toward St. Albans to the northwest. Two copses were behind the Lancastrian line, one of them between the fork in the two roads to the north and the other to the east along a side road that led to Enfield.

The Yorkist line from right to left consisted of the battles of Gloucester, Edward, and Hastings. Edward also established a dismounted reserve behind his division.

Barnet would be the first battle in which 19-year-old Gloucester would lead a battle of his own. Richard, who had been schooled in the art of warfare since childhood, would meet his first real test as a military leader. Edward ordered Clarence and his retainers to join his battle to keep a close eye on his brother and ensure he did not commit an act of treachery during the clash of arms. Hastings had the difficult task of attacking uphill against Oxford’s troops behind the hedgerow.

Although Edward had done an admirable job the night before of shaking out his marching column into a line of battle, he was not able to get his force directly opposite the enemy. Edward’s line was slightly east of Warwick’s line, which meant that each army’s right flank overlapped the other, giving Gloucester an advantage on the Yorkist side and Oxford an advantage on the Lancastrian side.

Edward had previously issued orders to his lieutenants to inform their troops that in the event of a victory they were only to only kill lords and spare the enemy levies. At some point before the battle began, though, he changed his mind and ordered no quarter given to any of the enemy in the event of a victory. His reason for the change of heart was probably to make sure that no survivors of Barnet joined the second Lancastrian army located in the West Country.

Fighting in the Fog

Both sides slept on the damp, cold ground unsure of whether the morning would bring exhilarating victory or dismal defeat for their side. Edward ordered his troops to fall in at 4 am.

During the night a fog had settled over the battlefield. The fog would make it impossible for each side to judge the other’s strength in the morning. When the sun rose at 5 am on Sunday, April 14, Warwick ordered his artillery and archers to fire on the Yorkists, even though it was impossible to see their exact position through the fog. Edward ordered his archers and handgunners to return fire. The handgunners, as they had in previous battles, proved to be largely ineffective.

Edward ordered the trumpeters to sound a general advance. Shouts and cries mingled with the sound of trumpets and drums, and the din that the voices and instruments made as they mingled together could be heard in nearby villages.

Hastings’ division encountered considerable difficulty closing with Oxford’s division behind the hedge. His troops, the majority of whom were recruited from the Midlands where Hastings had large estates in Leicester and Northampton counties, had to hack their way through bramble to reach their foe. Unknown to them, farther west beyond their flank several hundred of Oxford’s men, who were clad in the red livery with a star with streamers for their badge, plunged through the thicket and appeared unexpectedly on Hastings’ flank. With loud shouting the Lancastrians began slashing their way into the side of Hastings’ line.

Breakthroughs on the Flanks

After 30 minutes of fighting, the left of Hastings’ division crumbled. Before Hastings could redeploy his men to meet the flank attack, his entire line broke. Oxford’s men charged into the broken line swinging their swords and axes in an orgy of gore and death. The survivors streamed south across the heath leaving a bloody tangle of their dead and dying comrades to be trampled by Oxford’s exultant troops. The rout on the Yorkist left was not surprising considering that Hastings and his captains had not had sufficient time to drill the large number of green levies in their ranks before the battle.

Oxford’s men chased the fleeing Yorkists through the fog. When they overtook individuals or groups, they struck them down from behind and hacked them to death as they lay on the ground. A significant number of the survivors fled through Barnet and continued south toward London.

The same advantage of overlapping the enemy flank that Oxford’s men exploited on the west end of the battlefield was afforded to Gloucester’s troops on the east end of the battlefield. Gloucester led his men forward along ground that gently sloped upward toward Exeter’s men, who were deployed on open ground. They were clad in blue and red livery and wore a boar badge. Exeter’s men, clad in the duke’s red and white livery adorned with a fiery yellow beacon for a badge, braced themselves for the assault.

Ironically, Gloucester had been trained to be a knight under Warwick’s instruction at Middleham Castle. Having been informed before the fighting began that morning that there appeared to be no resistance opposite his extreme right flank, Gloucester had directed several companies to take advantage of the exposed nature of Exeter’s left flank. The flankers were to get behind Exeter’s line and assail it from three sides.

While Oxford’s troops were pursuing Hastings’s fleeing men, Gloucester’s men were steadily pushing back Exeter’s troops. As the fighting rose in fury, those that fell dead or wounded were trampled by others pushing forward to make the most of a local success. When he learned that Exeter’s line was wavering, Warwick ordered the reserve to march to Exeter’s assistance.

Rotating the Line

Edward’s troops in the center benefitted from the king’s presence. Their morale surged like high tide on a full moon. Swinging their swords, axes, and bills, they forced Montagu’s troops backward in the opening minutes of the fight. Edward repeatedly led fresh charges into Montagu’s line, swinging his sword with mighty strokes. He and his household troops made great inroads in Montagu’s line. When Warwick observed Montagu’s troops giving ground, he gathered up whatever fresh men he could find and led them forward to assist his brother. Then, he returned to the rear to try to get some feel for how the fighting was going on other parts of the battlefield. By the end of the first hour of fighting, Montagu’s larger numbers enabled him to halt the backward movement of his battle.

The two sides had begun the battle facing each other on an east-west axis, but with the left flank of each army either retreating or in rout, the line gradually rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise so that it was aligned with the Great North Road. Edward, who was in the thick of confused fighting in the center, did not discern through the thick fog that his left flank had been routed.

Since Oxford had no way of knowing that his men would so easily overrun Hastings’s command, he certainly had not given his men permission to pursue the fleeing Yorkists. While the rest of the Lancastrian line remained heavily engaged with the enemy, it was his responsibility to try to halt the pursuit to the extent possible. Thus, Oxford and his captains ran after their men. After a long delay, which must have seemed a lifetime to the earl, he and his captains regrouped 800 men in the fog-choked heath and led them back toward the hedge.

Oxford most likely thought he would be able to lead his reorganized command directly into the rear of the center of the Yorkist army. However, he was not aware that the line of battle had dramatically shifted and was now on a north-south axis. This meant he was actually leading his men toward the right flank of Montagu’s battle.

“Treason! Treason!”

By this time Montagu was acutely aware that his right flank was undefended. After nearly two hours of hard fighting, he and some of his men noticed a body of troops approaching from the south. Flying above them were banners with what appeared to be Edward’s badge of the sun with streamers, but in actuality was Oxford’s badge of a star with streamers. Believing he had been outflanked by Edward’s men, Montagu ordered a group of archers nearby to fire on the advancing column.

Montagu’s archers fired several volleys into the advancing troops. The arrows killed and wounded a number of Oxford’s men.

Under fire by Montagu’s archers, Oxford’s men were quick to believe that Warwick had switched sides in the middle of the battle, and they shouted, “Treason! Treason!” Oxford’s troops, which he had labored so hard to reform, immediately broke ranks and fled from the battlefield. The shouts of treason were heard by Montagu’s men, and the Lancastrians began to fall back as they tried to comprehend what was happening around them.

Edward sensed a pivotal moment had arrived, and he ordered his reserve into the fight. Despite the commitment of Warwick’s reserve to the Lancastrian left, Gloucester’s troops also sensed that the tide had shifted and laid into Hastings’s battle. Montagu’s battle gave way under the added pressure of the Yorkist reserve. His line broke, and the men fled north. Exeter’s troops also fled.

Death of the Kingmaker

The fighting was over well before noon. Yorkist men-at-arms had closed on Montagu’s position and cut him down. After briefly trying to rally the retreating Lancastrians, Warwick realized the day was lost and tried to make his way to where the horses were tethered. Encumbered by his armor while moving on foot, Warwick was easily overtaken. The Yorkists knocked him down. One of them pulled up his visor and stabbed him in the throat. The Kingmaker was dead.

Exeter, who lay seriously wounded on the battlefield, initially was stripped of his armor by Yorkist levies who were systematically plundering the dead and wounded. He was identified among the wounded later in the day and taken to a safe place so that his wounds could be dressed. Edward subsequently imprisoned Exeter in the Tower of London. Oxford, Beaumont, and Oxford’s two brothers were able to escape and in time made their way to Scotland with a small body of men.

The surviving Lancastrians fled north. They hoped to reach various forests along either the Great North or St. Albans roads where they might hide until darkness. Many of them were slain before they could reach the copses.

As for the Yorkists, Lords Say and Cromwell were among the dead. In addition, Edward’s household troops, who made many charges into the enemy line with the king, had suffered heavy casualties. Edward dispatched messengers to London to convey news of his victory. When they arrived they found that some of Oxford’s men, who had ransacked homes in Barnet and failed to return to their unit, had continued to London and mistakenly reported that the Lancastrians had won the battle.

The casualties on both sides were about 1,500. That Warwick as Henry VI’s lieutenant was able to bring so large a host against rival Edward was a feat in itself. Nevertheless, he lacked Edward’s charisma and ability to spur his troops to great feats despite the odds.

Rather than order the bodies of Warwick and Montagu mutilated and displayed on the gates of London, Edward ordered them taken into the city. It was said that Edward afforded them the courtesy because he believed that Montagu, who had done him great service, had reluctantly taken up arms against him. The bodies were loaded in a farm cart and hauled into the city where they were displayed for three days at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Afterward, Edward ordered the bodies taken to Bisham’s Abbey in Berkshire, where they were buried alongside their parents.

The same day that Edward destroyed Warwick’s army north of London, Princess Margaret and her son landed at Weymouth in Dorset. After a period of recruiting in the West Country, the Lancastrians marched toward Wales, where they hoped to raise additional troops. Edward moved to block them, and on May 4 the two armies met in battle at Tewkesbury. The death of Prince Edward of Wales during the battle and Somerset after the battle meant an end to Lancastrian claimants to the throne. The only remaining heir was 14-year-old Henry Tudor. Two years after Edward’s death in 1483, King Richard III would face Henry Tudor in battle at Bosworth Field.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments