By David A. Norris

Before dawn on September 21, 1745, the dragoons and infantry of King George II stood in line of battle in a freshly harvested wheat field. Only occasional drum rolls signaling some last-minute shuffling of troops disturbed the silence. It was too dark to see much of anything to begin with, and the field was shrouded in fog rising from the waters of the Firth of Forth on one side and a stretch of marshland on the other. The first light of the new day seemed to reveal a long hedgerow slowly materializing several dozen yards ahead of them. It soon became apparent that the “hedge” was moving. In a few moments, wielding Highland broadswords, daggers, and frightening edged weapons forged from scythes, the army of “Bonnie Prince Charlie” hurried the redcoats. That dark, misty morning at Prestonpans, Scotland, marked the beginning of the last great uprising of the Scottish clans in favor of the House of Stuart.

The Glorious Revolution

When James II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution in 1688, the House of Stuart remained in control of Great Britain. James’s eldest daughter took the throne as Mary II, ruling with her husband, William of Orange. On their deaths, Mary’s sister Anne ruled Great Britain. Queen Anne died in 1714, leaving no heir. The nearest Protestant claimant was the little-known ruler of a German duchy: George, the Elector of Hanover. In London he reigned as George I, beginning the House of Hanover. The new King George had been 52nd in line to the British throne, but he was the first non-Catholic male in the line of succession.

Numerous opponents in Scotland and England, among them British Catholics and Scottish nationalists, still supported the Stuart claims. In 1715, after some smaller failed attempts, a major uprising called “The Fifteen” broke out in favor of James Francis Stuart, James II’s son. He was considered to be James VIII of Scotland and James III of England by his followers, who were called Jacobites (Jacobus was the Latin equivalent of James). James Francis Stuart was called “the Old Pretender” by the Hanoverians. The would-be king lived in exile at the Palazzo Muti, a residence in Rome supplied by the Papacy to whom they regarded as the rightful (and Catholic) ruler of Great Britain.

After “The Fifteen” was crushed, another Jacobite plan failed in 1719. Thirty years after “The Fifteen,” the year 1745 found England entangled with France in the War of the Austrian Succession. The moment seemed favorable for another push to restore the Stuarts.

Support For Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Rebellion

James Francis Stuart was still living in 1745, but this time his son Charles Edward Stuart, known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” “the Young Prince,” or “the Young Chevalier,” led the rebellion. Born in the Palazzo Muti in 1720, the Stuart prince was raised in Italy. His education was haphazard, but he picked up several languages and was a skilled horseman and marksman. Jacobites began to see the bright lad as a potential champion to restore the Stuarts to the British throne.

Britain’s rivals, France and Spain, offered support to the Jacobites, but this support was always limited and subject to sudden withdrawal for diplomatic or strategic concerns.

In January 1744, the French were at last ready to aid the Stuarts again. Prince Charles slipped away from Rome while pretending to be on a hunting trip to join the French invasion fleet. A storm battered the ships while they were at anchor, and plans for official French help were set aside once again. Months of delay followed, until the patience of the Young Prince ran out. He vowed to journey to Scotland the next summer, even if he had only a single footman to go with him.

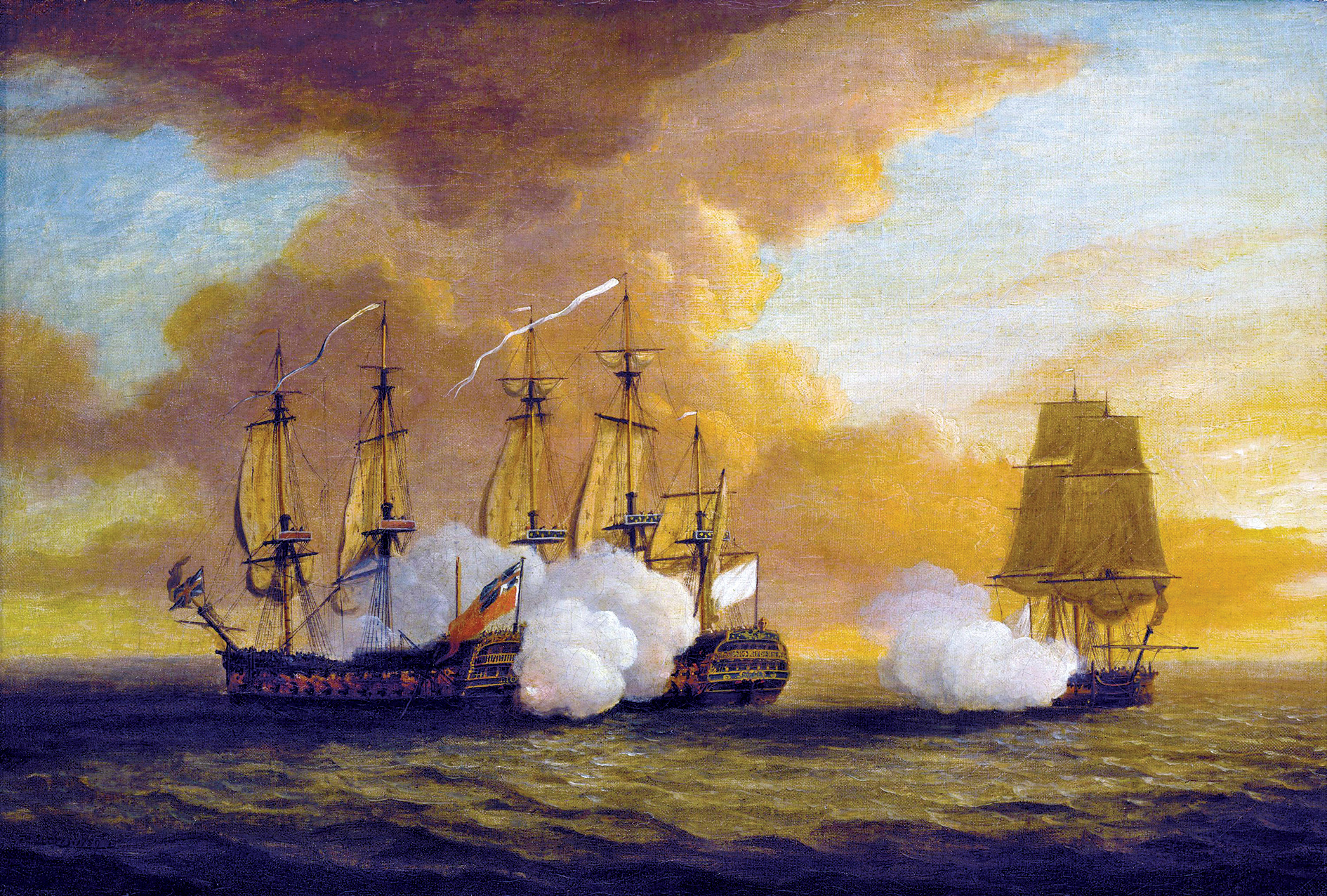

Charles Edward Stuart began putting together his own plans with donations and loans from Jacobite backers. Franco-Irish merchant Antoine Walsh provided an 18-gun vessel called the Du Teillay (also spelled Doutelle). France provided help in the form of a 64-gun ship-of-the-line, the Elizabeth. Aboard the Elizabeth were a few hundred soldiers of Clare’s Regiment, a unit of Irish soldiers in the French service. Also aboard the Elizabeth were 3,500 muskets, 2,400 broadswords, 20 guns, and a financial war chest of 4,000 gold louis d’or. They sailed from Nantes on June 22, 1745.

A chance encounter with the Royal Navy nearly ended the rebellion before it started. The Lion, a 58-gun Royal Navy ship-of-the-line, sighted the prince’s ships in the English Channel on July 9. About 5 pm, the Lion and the Elizabeth drew within range of each other and commenced a five-hour duel with cannons. The little 18-gun Du Teillay was driven back by the stern-chasers of the Lion and took no part in the battle. After dark, the Elizabeth was so badly damaged that she could never make it to Scotland. She steered for France carrying the Irish troops and most of the military equipment. The prince, though, brushed aside suggestions that he return to Europe and wait for another chance to start over. Fortunately for the rebellion’s planners, the Lion had been knocked around so much that her crew could only watch as the Du Teillay escaped.

Setting Foot in Scotland

On July 23, the Du Teillay anchored off the Outer Hebrides island of Eriskay. Charles Edward Stuart went ashore and, for the first time in his life, set foot in Scotland. Eriskay today has an unusual concentration of pink convolvulus, a wild flower said to grow nowhere else on the Hebrides. Known there as “the Prince’s Flowers,” they are traditionally said to descend from seeds dropped from the pockets of Bonnie Prince Charlie on that hopeful day.

Disguised as an Irish priest, the prince took shelter on a small farm that belonged to an islander named Angus MacDonald. Asked if he could furnish them a place to sleep, MacDonald had no idea who he was addressing when he bragged that his humble stone cottage had a bed and sheets that “a prince need not be ashamed to lie in.”

Leaving Eriskay, the prince landed secretly on the mainland of western Scotland at Moidart on July 25. With his troops on the Elizabeth lost to him, the rebellion started with only a handful of comrades, later known as “the Seven Men of Moidart,” standing by the Stuart claimant. The Young Chevalier hoped to persuade the leaders and the people of Scotland to rally to him.

The nobility of Scotland held titles as part of the peerage of Great Britain, but more important to the prince was their status as heads of the ancient Scottish clans. Each chief who joined the rebellion could bring hundreds of men with him. But for some days, the prince found the Scottish chiefs skeptical about risking everything to join another rebellion. The first important convert to the cause was Ranald MacDonald, the 23-year-old son of the Baron Clanranald. Although his father declined to join the rebellion, the son was so moved by the determination of the prince that he threw in his lot with the Jacobites, bringing 250 men with him.

News of the landing of Charles Edward Stuart began to attract more allies as well as to alarm the Crown’s officers in Scotland. Two companies of infantry under Captain John Scott were ordered from Fort Augustus to reinforce Fort William. By August 16, they were at Highbridge, a crossing of the River Spean about eight miles from their destination. Scott’s companies ran into Donald MacDonald of Tiendrish and a dozen men of the MacDonalds of Keppoch, one of whom was a piper. The MacDonalds drove the redcoats from the bridge and captured them.

On August 19, at Glenfinnan on Loch Shiel, Prince Charles openly raised his standard for the first time. He had barely 300 men, mostly the adherents of young Clanranald. Hope arrived on the scene when the prince and his men heard the sound of bagpipes. It was Donald Cameron, Lord Lochiel, with 800 men. Soon, 300 more men marched to the scene, the Keppoch MacDonalds who had captured the British at Highbridge.

Advantages and Drawbacks of the Jacobite Forces

Within a month, the Jacobite army had grown to about 2,500 men. Often referred to as a Highland army, it did indeed draw its initial support from that region of Scotland. But the Stuart cause drew support in the Lowlands of southern Scotland as well, and there were English adherents who disliked the House of Hanover for religious or political reasons. Meanwhile, many new soldiers for the Crown regiments raised to put down the rebellion were recruited in Scotland. Far from being the mob of wild barbarians depicted in Hanoverian propaganda, the Jacobites were organized into companies and regiments similar to the comparable English units. Some men came under obligations to their feudal lords, while others were volunteers.

At this stage of the rebellion, the high morale of the Jacobites was unaffected by some serious drawbacks. There were only about three dozen cavalry, and not a single piece of artillery. Most of the muskets supplied by the French were lost when the Elizabeth turned back, and only part of the rebel volunteers owned firearms to bring along.

At any rate, in those days the Highlanders did not rely on the flintlock as heavily as English or other European troops. In combat, they typically discharged their firearms at the beginning of a battle, then dropped them and rushed the enemy troops with swords and other edged weapons. In an age of short-range, single-shot muskets, such a bold onrush might well overwhelm one’s adversaries.

Foot soldiers who did not own swords carried improvised weapons fashioned from threefoot-long scythe blades mounted on long poles. The Jacobite infantry also carried a traditional Scots weapon used for defense as well as attack, the targe (or target). A small shield about 20 inches or so in diameter, the targe was made of animal hide stretched over a wooden frame. Turning the shield into a deadly offensive weapon was a sharp, foot-long metal spike fastened in the center of the outside of the targe.

The targe was an effective counter to the bayonet. A Scots foot soldier would crouch and deflect a musket and bayonet upward, pushing an infantryman’s only weapon out of the way and opening the path to a fatal stroke from a dagger or a broadsword.

Sir John Cope of the British Army

Leading the Crown’s response to the growing threat was Lt. Gen. Sir John Cope. Born in 1690, Cope was commissioned as a cornet in the Royal Regiment of Dragoons in 1707. He rose steadily through the ranks and was knighted for his service in the War of the Austrian Succession. His long service was adequate rather than brilliant, and he rose to high rank and a seat in Parliament through patience and influence rather than proven skill. He was appointed commander in chief of the British Army in Scotland in 1745.

On paper, Cope held considerable advantages over the insurgents. After the uprisings of the 1710s, the Crown built new military roads for quick transfers of troops into the Highlands. Three large strongholds, Forts William, Augustus, and George, helped cement a tighter grip on the conquered territory. But the demands of the War of the Austrian Succession took nearly all of the redcoats from Scotland to fight in Europe. Cope later referred to the forts’ remaining manpower as “the standing Garrisons of Invalids in the Castles.”

The Crown’s forces had definite news of the landing of Charles Edward Stuart by August 9. After losing several days to gather rations and horses, Cope marched his four regiments of infantry out of Stirling on August 20, bound for Fort Augustus.

The “Canter of Coltbridge”

On August 26, learning that the Jacobites held Corrieyairack Pass and blocked his march to Fort Augustus, Cope changed his plans and marched east to Inverness. This move left only two dragoon regiments near Edinburgh between the rebel army and southern Scotland and England. The rebels took advantage of the situation and marched south toward the Lowlands of Scotland.

The Jacobite army took Perth on September 4 and turned its eyes on Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. No troops were available to defend the city except for Gardiner’s Dragoons and Hamilton’s Dragoons, two horse regiments encamped just outside of town at Coltbridge. Lt. Col. James Gardiner was an experienced officer, but he knew his men were likely to prove unreliable. His regiment had just been recruited in Ireland for the war, and his men so far had little training.

On September 16, a handful of Jacobite horsemen rode ahead to survey the enemy positions outside Edinburgh. When the horsemen of the Young Prince encountered a small picket detachment of dragoons, the Highlanders drew their pistols and fired. This small flurry of shots put the guards into flight. Rushing toward the main dragoon camp, they infected the entire force with their panic. With their officers shouting at them in vain, both regiments stampeded away in a disgraceful show called the “Canter of Coltbridge.”

Rather than make for the walls of the city or Edinburgh Castle, the dragoons rode helter-skelter away from town. The road they took was “strewed … with accoutrements of every kind—pistols, swords, skullcaps, &c.,” according to Alexander Carlyle, a volunteer for the king’s army who was also the son of a local minister. Their flight ended after nightfall at the village of Preston, about 10 miles east of Edinburgh. Around Preston, coal seams ran right to the surface, and the ground had been pocked with shallow coal mining pits since the Middle Ages. When the dragoons halted to make camp, a man bumbling about in the darkness splashed into a coal pit partly filled with water. The unfortunate soldier’s shouts for help were taken as war cries of attacking Jacobites and ignited a fresh round of panic.

Cope’s Forces of the Crown

After Cope heard that the rebels were marching south, he left Inverness for Aberdeen on September 4. The march took a week, and after four more days getting his forces aboard ships, they sailed from Aberdeen on September 15. Two days later, they landed at Dunbar, roughly 30 miles east of Edinburgh. The dragoons of Hamilton’s and Gardiner’s regiments joined him at Dunbar.

In addition to officers, British infantry regiments of this era officially had 10 companies of 70 men each, and dragoon regiments had six troops of 59 men. In practice, regiments tended to be terribly understrength. To meet the rebel army, Cope had four foot and two dragoon regiments, which were the ones that had bolted from Coltbridge, and several other infantry companies. This totaled only about 1,400 foot, 600 dragoons, and 80 volunteers, according to Cope.

Most of them were infantry from four regiments: Murray, Lascelle, Guise, and Lee. At this time, British regiments were usually referred to by the commanders’ names rather than numerical designations. Some of the officers had decades of military experience, but the great majority of the rank and file were green recruits who had little training.

Six small 11/2-pounder field pieces, four coehorn mortars, and two larger royal mortars made up Cope’s artillery. Two staff officers, Lt. Col. Charles Whitefoord and Eaglesford Griffith, the Master Gunner of Edinburgh Castle, supervised the guns. In fact, the pair of officers had to fire the guns themselves because there were not enough trained men to have even one experienced hand at each gun. Cope’s pleas for more artillerists went unheeded. All of the enlisted personnel that could be provided were six gunners from the navy and four retired army artillerymen, three of whom were invalids. Whitefoord later complained that the “gunners who were borrowed from the men of war were generally drunk upon the march.”

Taking Position at Prestonpans

On September 20, Cope marched west along the road from Dunbar to Edinburgh. Coming to a large open field “about a Mile in Length, and three Quarters of a Mile in Breadth,” Cope believed he had found a spot “being very proper for us,” where he could deploy his cavalry and guns to good advantage. The field was bound to the north by the waters of the Firth of Forth and on the south by a ditch at the edge of a marsh. Carlyle described the field as “entirely clear of the crop, the last sheaves having been carried in the night before.” The field was empty of “cottage, tree, or bush … except one solitary thorn tree.”

Several villages were clustered around the broad meadow. At the western edge was the village of Preston, which was the place where the Coltbridge Canter had ended. Five hundred yards northwest of the village of Preston, Prestonpans was a somewhat larger village spread along the shore of the Firth of Forth. That place got its name from the iron pans used for the local salt making industry. North of the field, east of Prestonpans on the firth, were Cockenzie and Port Seaton; to the northeast was Seaton; and across the marsh to the south was Tranent. From the closeness of the other villages, the battle was also known as Preston, Tranent, or Gladsmuir, which was another village farther east of the battlefield.

Cope expected the Highland troops to attack from the direction of Edinburgh. So he deployed his men facing west in a line running roughly north and south, with his left protected by the marsh. Some distance in their front, the end of the field was blocked by a high park wall around the grounds of a manor called Preston House. A narrow passage separated the walls of Preston House from the walls around another manor, Bankton House. This 17th-century residence was the home of Colonel James Gardiner of the dragoons.

Cope was pleased with the position, declaring, “There was not in the whole of the Ground between Edinburgh, and Dunbar, a better Spot for both Horse and Foot to act upon.”

The Young Chevalier’s army approached Prestonpans, and the prince and his commanders also liked the ground they saw. Instead of confronting the king’s troops from the west as Cope expected, the Highlanders approached from the south, finding an advantageous position on high ground in the village of Tranent. The redcoat battle line shifted to face south, behind the ditch running along the northern edge of the swamp. Cope reported that during the afternoon he observed rebels occupying the churchyard at Tranent. Two field guns opened fire on the Jacobites, “which killed some of them, and soon dislodged them,” according to a royal government account.

Highlanders Moving Through the Marshes

Because of the marsh and the ditch running along its northern edge that formed a natural moat for the redcoats, the Highland commanders abandoned the idea of attacking from Tranent. Maneuvering continued all night as both sides shuffled their troops. British patrols reported about 3 am that the rebels were moving toward the eastern edge of the plain as if to attack the Hanoverian left flank. Cope redeployed his forces, shifting to the east and placing them in a line running north to south.

During the night, Lord George Murray had proposed the army move to attack from the east. Robert Anderson, a local whose father owned the marshland south of the redcoats’ position, told the Highlanders of a shortcut through Riggonhead Farm at the eastern part of the marshes, which would save them considerable time in marching. In the lead was the Duke of Perth, leading the troops of the Clan MacDonald. Following were Lord Murray and his men, with the Young Prince himself marching with them. Crossing one of the ditches in the dark, the prince stumbled and had to be helped back on his feet.

By 5 am, the Highlanders were through the marshes and arranged in two lines for the attack. Centuries-old custom placed the MacDonalds on the right of the front line. The Camerons and the Appin Stuarts made up the left, and the MacGregors and the Duke of Perth’s regiment held the center. Commanding the right was the Duke of Perth, while Lord George Murray led the left. Perth moved considerably to his right to allow Murray’s men to keep clear of the marsh. By a stroke of good fortune, this permitted Perth’s line to extend 100 yards beyond Cope’s left. Fifty yards behind the front was the second battle line, with the Young Prince in front.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart briefly addressed the men, telling them, “By the blessing of God I will this day make you a free and happy people!” The first faint glow of the day’s light barely illuminated the assembled Highlanders. Mist rose from the marshes as the Highlander battle line pushed forward. At first, there was no noise to be heard from the Jacobites other than the sound of their feet going through the stubble in the recently harvested wheat field.

The Highlanders in the front line crouched low, using their shields as cover. At their first sight of the enemy in the dim half-light, the approaching battle line looked to the government troops like a hedge, but its true nature was gradually becoming apparent as the light increased. Dragoons covered the flanks of the king’s infantry. Rather than spreading the field guns and mortars throughout the line, the Hanoverian guns were all deployed on the right flank. Whitefoord and Griffiths being the only experienced artillerists, the pieces were kept together for them to handle.

“Fire on My Lads, and Fear Nothing”

As the Highland troops advanced, Whitefoord looked for his naval gunners, but they were nowhere to be found. All 10 of the enlisted men assigned to the guns had fled. Whitefoord fired five of the 1½-pounders himself. The fleeing gunners had taken the priming for the sixth gun, leaving it mute and useless. Griffiths fired each of his mortars once. In the darkness and confusion, he never knew whether any of his “shells broke or not … they having been long in store in Edinburgh Castle, prepared, and many of the fuzes damnified,” according to a government account.

On Cope’s left, Hamilton’s Dragoons turned and fled when the firing began. Left without their support, few of the infantry reloaded after firing their first single volley. The redcoat line disintegrated as the soldiers fled or tried to surrender. So quick was the collapse that the second line of the Highlanders, 50 yards behind the front formation, found no enemies save the dead or wounded.

On the Hanoverian right, the little guns had done little to slow down the advancing Jacobites. Whitefoord and Griffiths were captured as the Highland tide swept over and past their guns.

A squadron of Gardiner’s Dragoons posted near the guns fled, riding through and over the troops guarding the artillery. Gardiner led another squadron personally, but as he feared, his men quickly melted away. Near the ground abandoned by the dragoons was a small cluster of infantrymen who were holding fast. Gardiner rode toward the resolute foot soldiers, shouting to encourage them, “Fire on my lads, and fear nothing.” A moment later, a Jacobite slashed the colonel’s arm with a scythe fastened to a long pole. Gardiner’s sword fell from his hand. Dragged off his horse, he received a mortal blow, probably from a broadsword. The colonel’s servant heard his last words: “Take care of yourself,” as the officer fell near the lone thorn tree on the field.

Most of Hamilton’s and Gardiner’s Dragoons rode around or through the village of Preston. As the Highlanders had almost no cavalry, the dragoons made their escape. Cope and some other officers were swept along with perhaps 400 horse soldiers. Efforts to rally the men were in vain until the mob reached St. Clement’s Wells, two miles from the battlefield. There, Cope and the officers halted and gathered a small force of dragoons by threatening them with drawn pistols. But a pistol accidentally fired and threw the whole lot again into panic.

The British Rout

As the infantry regiments crumbled, their men ran toward the west. An officer in Lee’s Regiment, Captain Sir Peter Halket, kept his company together in the maelstrom. Retreating to Tranent Meadow, Halket’s company found cover in a ditch and held on for some time until the Jacobites let them surrender on terms. Halket later rose to the rank of colonel but did not survive another disaster 10 years later. With many men of Lee’s Regiment, which was by then designated the 44th Regiment of Foot, he was killed at the Battle of the Monongahela, or “Braddock’s Defeat,” at the beginning of the French and Indian War in 1755.

Carlyle wrote, “Hardly more than ten or fifteen minutes after firing the first cannon, the whole prospect was filled with runaways, and Highlanders pursuing them. Many had their coats turned as prisoners, but were still trying to reach the town in hopes of escaping.” But for most of Cope’s foot soldiers, any hope of escape was fatally blocked by the walls surrounding Preston and Bankton Houses. Trapped by masonry that was too high to climb over, scores of redcoats “huddled together … in a confused drove” were slaughtered.

The Scots poet Dougal Graham wrote:

The poor foot, left here, paid for all,

Not in fair battle, with powder and ball;

But horrid swords of dreadful length,

So fast came on, with spite and strength,

Lochabar axes and rusty scythes….

According to most accounts, the Battle of Prestonpans was over within 10 minutes. Indeed, as Graham wrote, it was the infantry that “paid for all.” Estimates of the king’s losses ran from 150 to 300 or more dead and 1,300 or more taken prisoner. Perhaps a quarter of the royal dragoons and nearly all of the infantry were casualties. In contrast, the army of the Young Prince lost about 30 dead and 70 to 80 wounded.

Prince Charles ordered his men to spare the lives of their prisoners, halting the slaughter by the walls of Preston House. He insisted that the wounded get the best possible treatment. Most of the dead were buried near where they fell, along the park walls, or around the lone thorn tree near the original battle line. Local folk buried the bodies by “carting quantities of earth, and emptying it upon the bloody heaps,” according to one account of the battle.

Gardiner’s servant secured a cart and returned to the battlefield disguised as a servant of a local miller. He found the colonel unconscious but breathing, plundered of his watch, his upper garments, and boots. The servant conveyed Gardiner to the church at Tranent. Placed in a bed in the minister’s house, Gardiner died about 11 am. While Gardiner lay dying, his house nearby was first plundered and then hastily converted into a makeshift hospital.

Also captured were the supply wagons and the regimental records and papers of the king’s forces. Some of the victorious Jacobites turned their attention to plunder after the battle. Poor men wearing shabby and ragged clothing picked up fine laced coats and cocked hats. A considerable supply of chocolate was captured with Cope’s baggage. Chocolate was so unfamiliar to the Highlanders that some of this loot was sold as a medicinal ointment called “Johnny Cope’s Salve.” Another fellow was said to have gladly sold a captured gold watch for a pittance, for it had, in his words, “died the night before.” The captor didn’t know that he had to wind the watch to keep it working.

Word of the Defeat at Prestonpans

Cope halted for the night in Coldstream before riding to Berwick and sheltering in the fortifications. “He everywhere,” wrote historian John Home, “brought the first news of his defeat.”

Some of the townspeople of Edinburgh received their first news of the battle about one hour after the first shots were fired, when they saw a party of dragoons galloping up the principal street. The townsfolk saw the dispirited men fleeing from a single rider, a Jacobite named Colquhoun Grant who rode a horse taken from a slain English officer. Foiled by finding his quarry bolted safe in Edinburgh Castle, Grant stuck his bloody knife into the gate. He then rode out of town, and no one bothered him.

As news of Prestonpans crossed the English Channel, France was willing to openly aid the Jacobites. By October, French cannon, arms, and soldiers were being landed in Scotland. Deciding to make a bold push for London, the Jacobite army crossed the border into England on November 8 and took Derby on December 4. London and the British throne were only 120 miles away.

Turning Back the Jacobite Tide

Derby was to be the highwater mark for the Jacobite cause. With only 5,000 men and little success adding English recruits, their forces were threatened by armies that numbered 30,000 men. Heeding cautious counsel, the Young Prince ordered a withdrawal to Scotland.

In another battle fought at Falkirk on January 17, 1746, the Jacobites again defeated a royal army, this one led by Lt. Gen. Henry Hawley. According to legend, Cope had bet Hawley that he, too, would lose a battle with the rebels. After the defeat at Falkirk, it was said, Cope collected 10,000 pounds.

Despite the Jacobite successes at Prestonpans and Falkirk, their defeat at the April 16, 1746, Battle of Culloden shattered their cause once and for all. The army of George II that confronted the Jacobites at Culloden was not the poorly prepared army of Prestonpans. Replacing the lost amateur redcoats of the early disaster, a new army assembled by the Duke of Cumberland was made up of experienced veterans of the fighting against the French and their allies on the Continent.

Cope went through a court of inquiry in September 1746. After considerable testimony, he was exonerated. Blame went to the hastily mustered and poorly trained troops under his command. In the popular mind, exoneration was not so easily won. The general is now also remembered for a mocking Scots folk song, “Hey, Johnnie Cope! Are Ye Waukin’ [Awake] Yet?”

Prince Charles Edward Stuart managed to escape capture after Culloden, but the rebellion that began so promisingly with the victory at Prestonpans would never be repeated. The Young Chevalier became a king at last, in name only, when his father died in 1766. When he died in exile on January 21, 1788, the last breath of “Bonnie Prince Charlie” was drawn in the same place he took his first, far from Scotland in the Palazzo Muti in Rome.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments