By Robert Heege

Almost from the beginning, the short, violent reign of Paraguayan strongman Francisco Solano Lopez devolved into a nightmare from which his unfortunate people could not awake. While still in his twenties, the youthful Lopez spent 18 months in Europe, an experience that made a deep impression on him. He was particularly taken with the glittering martial splendor of the court of French Emperor Napoleon III. Returning home, Lopez brought back with him several steamships to fill out the embryonic Paraguayan fleet, along with all the guns, ammunition, and gold braid that his deep pockets could purchase. He also brought back a new mistress, an Irish adventuress named Eliza Lynch, who, like many a gold digger before her, catered to her meal ticket’s outsized ego, recklessly encouraging his delusions of grandeur and dreams of imperial glory.

Latin America had only recently cast off the colonial yoke of the once mighty empires of Spain and Portugal. For many of the infant nations of South America, national borders were far from finalized and were often the subject of increasingly acrimonious debates. Worse still, the unseemly haste with which their former colonial masters had set sail for home had left the new nations with little experience in self-government, much less democracy. It was little surprise, then, that almost the entire continent soon became the domain of regional strongmen who ruled and plundered like modern-day mafiosi. Diplomacy consisted largely of machismo-laden ultimatums and gilt-edged saber rattling.

Sabre Rattling in South America

Lopez was one of the worst. In 1864, two years into his reign, the self-proclaimed Protector of the Equilibrium of the La Plata became miffed when Brazilians began meddling in the affairs of Paraguay’s southern neighbor, Uruguay. At the time, Uruguay was locked in a violent dispute between two rival oligarchies that were vying for control of the country. The Blanco faction, headed by Uruguay President Atanasio Aguirre, was fighting hard to stay in power. When Brazil threw its support behind the Blancos’ would-be replacements, the Colorado faction led by Venancio Flores, Lopez took it as a personal insult that he had not been consulted beforehand. If anybody was going to throw their weight around in Uruguay, it ought to be him. Lopez immediately declared his support for Aguirre and demanded that Brazil cease military support of the Floristos. The demand was pointedly ignored.

In an effort to drive home his point, Lopez in November 1864 seized a Brazilian merchant ship, the Marques de Olinda, which happened to be sitting at anchor in the harbor of Asuncion, the Paraguayan capital. On board was the governor of the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso, whom Lopez promptly threw into a dungeon. Scarcely a month later, in December 1864, Lopez ordered his armed forces to invade mineral-rich Mato Grosso, which was extremely underdeveloped, underpopulated, and undefended. After sacking the provincial capital at Cuiaba, Lopez smugly declared the entire province to be Paraguayan property.

As the self-appointed savior of the Aguirre government, Lopez, now calling himself El Supremo, rashly decided to send his army marching through the Argentine province of Corrientes to attack his perceived foes in Uruguay. When Argentinian President Bartolome Mitre coolly refused to allow Lopez to use his territory as a land bridge into Paraguay’s back door, Lopez abandoned all reason. On April 13, 1865, he had his rubber-stamp Congress elevate him to the status of Marshal of Paraguay and grant him extraordinary war powers. These he used to declare war promptly on Argentina.

Lopez followed the declaration by capturing two Argentine naval vessels in the Bay of Corrientes, then occupied the sleepy little town of the same name. Not content with anointing himself the new master of Corrientes province on the basis of this petty triumph, Lopez declared himself the new ruler of the adjoining province of Entre Rios as well. It was then that the would-be warlord’s luck began to run out. By this time, the Flores faction had managed to come out on top in Uruguay, whereupon the new regime promptly announced its intention to stand shoulder to shoulder with Argentina in its hour of need.

El Supremo Goes to War

On April 18, Argentina and Uruguay declared war on Paraguay. Two weeks later, with its own axe to grind, Brazil secretly threw in with Argentina and Uruguay, pledging to help bring all their forces to bear until the existing government of Paraguay should be overthrown and “no arms or elements of war should be left to it.” The stage was now set for a wide-reaching South American war. What had started as petty border squabbling among four countries united by history and (in three cases) a common language, was about to take a terrible turn. The little-known tragedy of the Paraguayan genocide was about to begin.

The opening shots in the conflict belonged to the Paraguayan navy. On June 8, 1865, Lopez, all gold braid and moustache wax, stepped out of his carriage in the harbor of Asuncion, ready to take the bit of history in his gnashing teeth. With all the hyper-inflated brio he could muster, he strutted down the queue and bounded up the gangplank of his flagship, the small gunboat Tacuari. The order was given to make way at once. With that, Tacuari, the gunboat Alhambay, and 16 other motley vessels of varying size and description set sail for Humaita, a fortress on the Parana River. Not far from there, at a wide point in the Bay of Corrientes known as Riachuelo, a Brazilian naval squadron consisting of nine ships was already preparing to support a ground force charged with driving the Paraguayans out of Corrientes and Entre Rios.

For two days, Lopez holed up in Humaita. Then, in the predawn hours of June 11, despite his utter ignorance of naval strategy and tactics, he personally ordered an attack force of nine ships (about half his navy) under the command of Commodore Pedro Inacio Meza to move against the Brazilians at a wide point in the river called the Riachuelo. Trailing the squadron into the fray were a half dozen floating coffins known as chatas. These were low slung, flat-bottomed barges, each armed with a small cannon, that were being towed out to meet the enemy. In all, the Paraguayan ships had a total complement of 36 disparate guns. To support them, Lopez had a shore battery wheeled into place along the banks of the Parana. Lopez himself never left the fortress.

Naval Duel For the Parana

Facing off against Meza was Brazilian Admiral Francisco Manuel Barroso. He, too, had nine vessels. There the similarities ended. The Brazilians had better ships, better trained seamen, and above all, better firepower—a total of 59 guns. Making way at 2 am, the Paraguayan fleet chugged down the Parana in the vain hope of catching the Brazilians off guard at first light. Mechanical problems, including a temperamental engine on one of the ships, scotched Lopez’s rudimentary battle plan. At nine o’clock in the morning, under a glaring, unforgiving sun, before Meza and his attack force reached Riachuelo, the chatas slid into position along the river bank to form a makeshift shore battery. The Brazilians, anchored nearby, watched with open mouths.

With the element of surprise irretrievably lost, Meza, though far from being a Nelsonian tactician, proved that he was a man who knew how to obey orders. He simply pointed his ships directly at the Brazilians and launched them like torpedoes at the enemy vessels. Then he had each of his commanders face off against a particular ship and open fire. The Brazilians, for their part, were quick to return fire. The bay seemed to shudder as the two sides began pounding away at each other in a thunderous bombardment. In the midst of the melee, the Brazilians forced a breakout from the channels. Barroso was no fool. He knew that if the Paraguayans continued boring in on him, his squadron was in danger of being split in two.

Each Meza commander continued to dog a particular enemy ship during the fight. The Riachuelo began to resemble a kind of murderous square dance. At one point, the two sides actually exchanged positions. Meza spent the rest of the battle desperately trying to lure the Brazilians back into the narrower channels, where his smaller ships’ superior maneuverability might enable them to gain the upper hand against the larger Brazilian vessels.

The strategy almost succeeded. One of the Brazilian ships, Belmonte, got too close to the shore batteries, and the chatas, flimsy though they were, managed to put several cannonballs into her side. Recoiling from the fusillade, two of Belmonte’s sister ships, Parnaiba and Jequitinhonha, got caught on sandbars in the shallows. The Paraguayan ships closed in like piranhas and managed to sink the lumbering Jequitinhonha. Parnaiba was boarded, and a fierce hand-to-hand struggle erupted on her decks for control of the ship.

In the end, Parnaiba’s crew managed to repel the invaders, and the superior firepower of the Brazilians carried the day. After sustaining the loss of five of his nine ships and all of the chatas either taken or blown out of the water, Meza, who had been gravely wounded in the fighting, was compelled to withdraw. He gave the order, and at one o’clock in the afternoon, a scant four hours after he had joined the Brazilians in battle, Meza and what was left of his command limped back to Humaita, where the admiral succumbed to his wounds a few days later.

The Birth of South America’s Triple Alliance

Lopez’s failure to gain control of the Parana had grave consequences for his territorial ambitions. Although his troops had begun making inroads into Corrientes and the Rio Grande area, capturing a few sleepy towns and villages, Meza’s defeat made their situation untenable. With the river at their backs on one side and the Brazilians on the other, a well-ordered tactical withdrawal was the only option that made sense. Predictably, Lopez wouldn’t hear of it. Flying in the face of military logic, he ordered his soldiers to continue their village-hopping campaign. The situation deteriorated rapidly.

On August 17, a combined force of 8,390 Brazilian, Argentinian, and Uruguayan troops under the command of the newly minted president of Uruguay, Venancio Flores, met the 2,700-man-strong second column of Lopez’s invasion force at Yatay and promptly broke its back. While Paraguayan casualties were not insubstantial, most of the column decided to simply cut and run, literally swimming for their lives back across the river into Paraguay. Four weeks later, Lopez’s remaining troops in the region, numbering about 5,200 broken men who were low on food, ammunition, and just about everything else, gave up and surrendered. The slow, inexorable immolation of Paraguay was about to begin.

Apart from a few desultory skirmishes, the Allies were content to let Lopez stew in his own juices for several months. Then, on April 16, 1866, the forces of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, officially christened as the Triple Alliance, staged a combined assault by land and sea across the Parana. The relative lack of martial subtlety in their battle plan was amply compensated by the sheer pugnacity of the forces making the attack. They went energetically about their task, scattering what was left of Paraguay’s naval defenses and completely overwhelming the fortress of Itapiru, whose less than stalwart defenders threw in the towel and evacuated on April 19. The day before, Argentina had sent an additional 60,000 men, led by their own president, onto Paraguayan soil. The gateway to Lopez’s kingdom had been forced wide open.

Slaughter at Tuyuti

As the Allied forces moved farther inland into Paraguay proper, Lopez and his army continued to pull back deeper into the interior. Except for a quickly repulsed Paraguayan attempt at ambush on a mud-soaked floodplain called the Estero Blanco, the only major hostilities were those that erupted between Argentine President Mitre and his Uruguayan counterpart, Flores. Each man considered himself the overall commander of the invasion. The two were continually at loggerheads.

Meanwhile, Lopez was marshalling his forces to the north, at Tuyuti, where he was hoping to reverse his fortunes. The ensuing Battle of Tuyuti, which began in earnest on May 24, would be the largest battle of the war. For Lopez, it was also an unmitigated disaster. In principle, the difficult, swampy terrain should have favored the Paraguayans, had they opted for a defensive posture. Against all military sense, however, Lopez bullied his officers into going on the offense. It was a terrible miscalculation. By ordering his troops to attack, El Supremo forced them to advance through the same natural obstacles that might have given his adversaries pause. Instead, the Allies dug in, and the Paraguayans were left with no alternative but to hurl themselves at an entrenched position with virtually no artillery support.

Blundering forward in a series of waves, the heat of the noonday sun beating down upon them, Lopez’s troops doggedly slogged through the reed-choked thickets as their adversaries opened fire. For every yard they gained, the Paraguayan ranks were decimated by shot and shell. The closer they got to the Allied positions, the more terrible the carnage became. Those few hardy souls who managed to get within reach of the Allied positions found themselves blasted to pieces by withering volleys of rifle fire. Entire battalions were lost.

It was a pointless slaughter. By the time the order to retreat was finally given, 6,000 Paraguayans lay dead in a hideous sprawl with an equal number of wounded thrashing about in the blood-soaked mud. In a single afternoon, Lopez had managed to throw away an entire army; he would never field another of equal strength. His predictable response was apoplectic defiance. He withdrew his remaining forces to a brace of fortified trenches and moats at Curuzu and Curupaity, which guarded the approaches to Lopez’s personal fortress at Humaita.

Paraguayans Besieged

Beginning in the last week of May and continuing through August, Allied forces made an ever-enfolding encirclement of Humaita. On September 2, the honor of leading the attack went to Brazil, when Admiral Joaquim, Marques Lisboa, threaded a fleet of 20 ships through mine-laced waters up the Parana until they loomed over the 2,500 Paraguayans huddling in the trench line at Curuzu. As soon as Lisboa’s ships began bombarding Curuzu, the 14,000 men of the 2nd Brazilian Infantry Corps commanded by the Viscount de Porto Alegre were transported via landing craft, D-Day style, onto the bank, whereupon they stormed the Paraguayan trenches and overwhelmed the defenders in vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

After Curuzu, the Allies paused to lick their wounds and gather reinforcements. Ten days passed, and on September 12, Lopez asked for a parley and actually met with the presidents of Argentina and Uruguay. Too much blood had been spilled for either side to stomach the notion of negotiating peace with the other, and the talks yielded nothing. After 10 days, hostilities resumed in earnest. At dawn on the 22nd, the Allies opened with another naval bombardment, which was answered in kind by the Paraguayans. Shelling continued on and off for the rest of the day. Then, at the stroke of midnight, the Allied forces, some five columns strong, pressed forward to Curupaity, where 5,000 Paraguayans arrayed in two lines of trenches were waiting for them.

The Allies breached the first trench but soon bogged down in the moat directly behind it. Lopez’s artillery batteries and riflemen began to pour fire onto the invaders. After losing at least one-fifth of their men, the Allies were compelled to call off the attack. The Paraguayan losses were a mere 54 men. After the debacle, neither Mitre nor Flores nourished any further desire for command. Blaming each other for the humiliation at Curupaity, both men beat an unseemly retreat back to their respective presidential palaces—and took most of their troops with them. Only 4,000 Argentinians and a token force of 200 Uruguayans remained behind in Paraguay to fight on with the Brazilians. It would be another 10 months before the Allies were ready to make another run at Curupaity and Humaita.

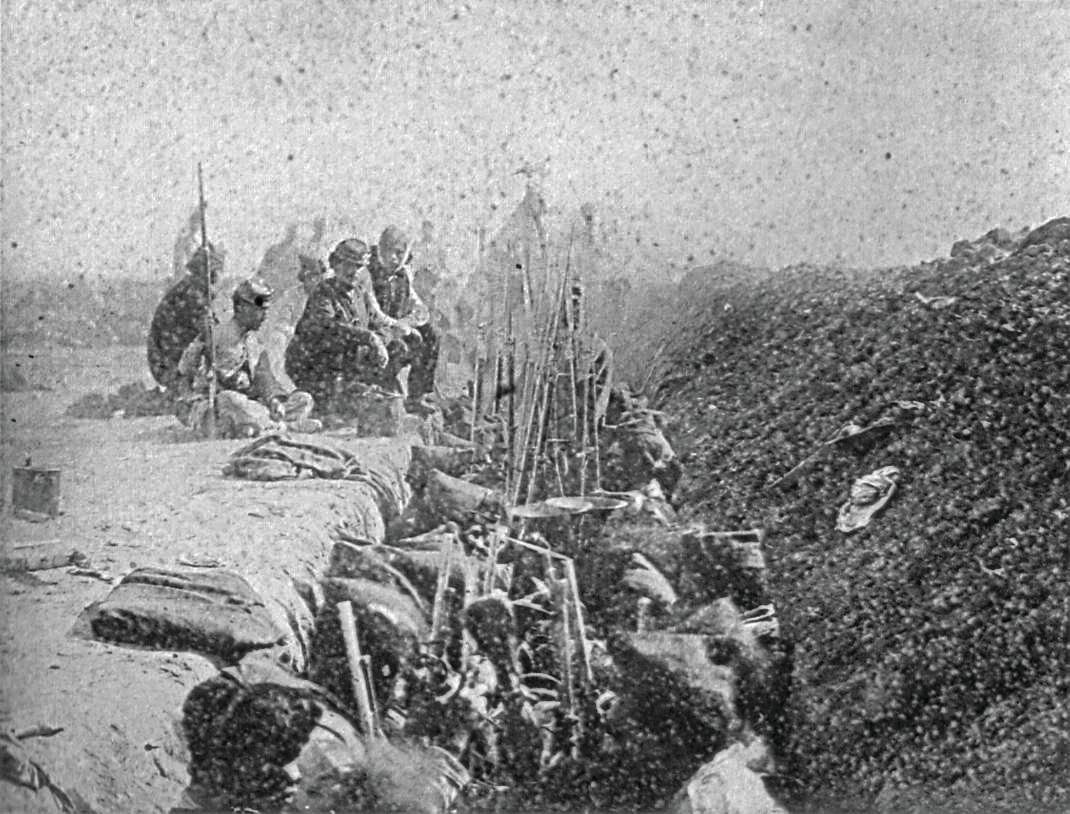

Meanwhile, the river blockade, which had been in effect since the early summer of 1865, forced Lopez to rely solely upon his ever-dwindling stores of men and materiel. While the Brazilians and their coalition partners had been amply reinforced and could now boast over 45,000 well-armed soldiers, Lopez’s troops were beginning to look like an army of saplings and old men. Almost all of them were manning what had become an even more elaborate system of trench works known as the Quadrilatero. At this point, they were relying in large measure on whatever captured ordnance they could scrounge from the dead on occasional nightly forays into the no-man’s-land between them and the enemy. Even unexploded shells from the Brazilian warships were dragged back to the Paraguayan lines. The siege dragged on through the summer of 1867.

The Capture of Humaita

The Triple Alliance gained a new commander-in-chief in the person of General Luis Alves de Lima e Silva, the Marquis de Caxias. Belying his noble birth, Caxias was a capable professional soldier who immediately drew up plans for a full-scale assault on the Quadrilatero. In order to outflank and encircle the Paraguayan trenches, Caxias dispatched his 1st and 3rd Corps north of Humaita through chest-high swamp water to knock out a gun battery that had been placed there, clearing the upper Parana of Paraguayan troops. On August 18, the Brazilian Navy forced passage around Curupaity. The Paraguayans manning the Quadrilatero hunkered down in their innermost positions and waited for the inevitable attack. By November 2, the encirclement was complete. At that point, communications between Humaita and Asuncion were cut.

The next day, Lopez and his vanguard surprised the Brazilians with an attempted breakout at a perceived weak point in their lines but were soon beaten back, at which point the siege was not only maintained, it was tightened. After a fierce struggle, the Brazilians captured the strategic redoubt at La Cierva and closed to within two miles north of the walls of Humaita. Paraguayan resistance was tenacious, however, and it took the Allies another three months before they managed to close the last two miles and start knocking out the trench works of the Quadrilatero one by one. The Brazilian fleet positioned itself just above the fortress and continue the naval bombardment with increased vigor.

On March, 3, 1868, with the Allies closing in fast, Lopez retreated, somehow managing to take between 10,000 and 12,000 men with him. Under the Allies’ collective noses, they slipped out of the fortress in the dead of night and hightailed it into the jungle, leaving behind Colonel Paulino Alen and some 3,000 unfortunates with orders to resist to the last man. Alen promptly retired to his quarters and shot himself. His second-in-command, a colonel named Martinez, managed to hold the fort until August 24, when, low on food and ammunition, he too attempted an evacuation under cover of darkness. Humaita fell that same night. By that time, Martinez had lost more than half his soldiers. He was captured along with the shattered remnant of his command on August 25. These men, at least, escaped the horror of what was to come.

The Child Soldiers of Francisco Lopez

After the fall of Humaita, the Brazilians devoted the next several months to a grueling village-hopping campaign of their own that ravaged the Paraguayan countryside. Following in their wake, a cholera epidemic further decimated the local population. In December 1868, the last few nails in Lopez’s coffin were ready to be driven home. After the ignominious fall of Humaita, the Allies chased Lopez northward for 140 miles through the green hell of the Paraguayan countryside. Reaching the port of Villeta, Lopez once again set his bedraggled troops to the task of digging defensive trenches. By now they must have felt as if they were digging their own graves.

On December 6, with Caxias moving ever closer, Lopez sent another hapless colonel, Bernardino Cabellero, and a force of 5,000 conscripts to intercept the Brazilians at a small bridge spanning the Ytororo River. The Paraguayans got there first, concealed themselves in the foliage, and waited. In short order, the Brazilians arrived on the scene. They were halfway across when the brush at the opposite end erupted with gunfire. Despite the hail of bullets, Caxias continued to urge his men on. A seesaw battle ensued, but each time the Brazilian troopers fell back, their commander exhorted them to press forward, personally leading the final push himself. The Paraguayans soon started running out of ammunition.

At that point, Cabellero and about 4,000 of his troops withdrew, leaving the remainder, including a handful of middle-aged campesinos and a host of underage boys, to face the enemy. As Caxias and his soldiers reached the far end of the span, the desperate Paraguayans, down to mostly machetes and rusty bayonets, left their positions and rushed forward to meet the enemy head-on in a suicidal charge. From there, the action quickly degenerated into a vicious, murderous brawl. The Brazilians’ superior numbers—and the simple fact that they still had bullets—carried the day. In a matter of minutes, the fight at Ytororo was over. Afterward, when the weary Brazilians began inspecting the enemy dead and realized that a sickening number of them were boys no older than 15, many of the soldiers wept.

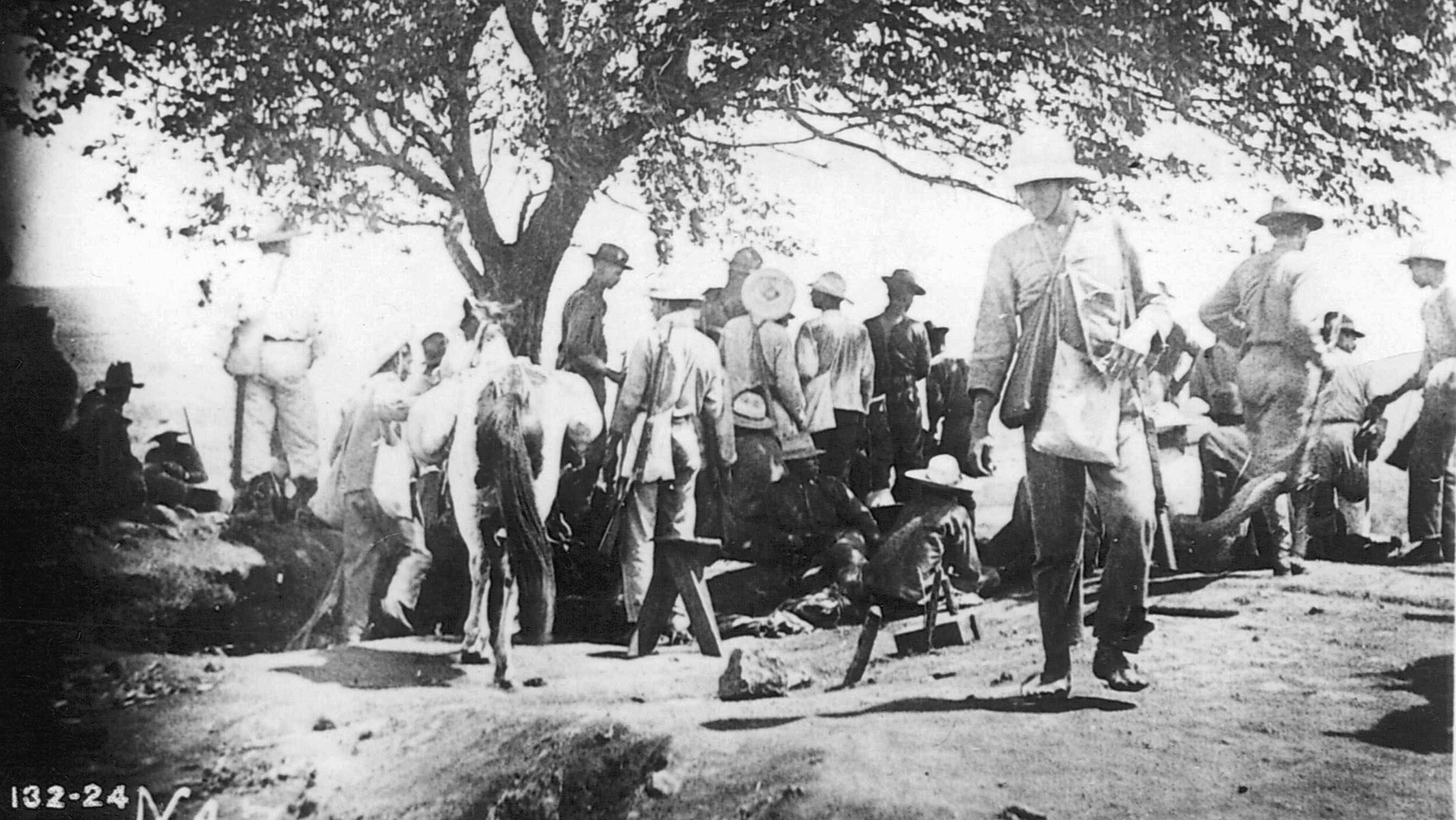

While 1,000 child soldiers were sacrificing themselves back at the bridgehead at Ytororo, Cabellero and the bulk of his force returned to Villeta. Lopez immediately ordered them to take up defensive positions once again, this time in an area alongside a stream that bordered the town of Avahy. On December 11, the Brazilians reached Villeta. Lashed by sudden torrential rains, Caxias and his army squared off against Cabellero and his ragged, ill-equipped expendables, whom they outnumbered 4-to-1. In heartrending contrast to the manpower at Caxias’ disposal, Lopez and his minions were scraping the bottom of the barrel. Cabellero’s remaining command was now comprised almost entirely of old men and children. Forced conscription under these conditions amounted to a death sentence. Whole battalions were cobbled together ad hoc, made up entirely of boys as young as 13 or 14. Untrained, barefoot innocents were made to face an army of battle-hardened veterans.

At Avahy, the adolescent volunteers struggled vainly for nearly four hours to hold back the enemy in a contest they only partially understood. With all the obstinacy of youth, they would not yield. Refusing all quarter, they received no mercy. Only a few hundred of Avahy’s defenders lived to see another day. The rest, numbering well over 3,000, were cut down. When the Brazilians entered Villeta, they found that Lopez had once again used his human shields to cover his escape. Caxias’ army was joined by 4,000 troops from Brazil’s reluctant ally, Argentina, and another 600 Uruguayans. Everybody, it seemed, wanted to be in on the kill.

Capturing the Capital

Increasingly bad weather hampered operations, but on December 21 a general mopping up of Paraguay’s scattered, disparate forces began in the Ita-Ibate hills of northern Paraguay and on the banks of the Pikisiri, another nondescript waterway in a land of jungle streams and snake-infested rivers. Just beyond the Pikisiri lay Angostura, Lopez’s last remaining stronghold. Attacking each of the positions simultaneously, Caxias spent the next six days of Christmas week grinding them down to powder. Two days after Christmas, on the morning of the 27th, having scoured the Ita-Ibate hills of Lopez’s loyalists, the Allies overwhelmed the remaining 6,000 Paraguayan troops. Yet again, Lopez himself was nowhere to be found.

Three days later, Colonel George Thompson, an English soldier of fortune who had hitched his cart to Lopez’s wagon, had the dubious distinction of surrendering the garrison at Angostura and its full complement of 1,750 beleaguered defenders, 400 of whom were female. The presence of so many women in the garrison was not a happenstance. Throughout the long ordeal of Lopez’ cycle of withdrawals and retreats, women had been routinely forced at bayonet point to carry stores and ammunition through the trackless tropical wilderness of the Paraguayan interior. Those who couldn’t keep up in the malarial heat were left to their fates.

On January 5, 1869, Caxias entered Asuncion, the Paraguayan capital. By then, the city had acquired the look and feel of a haunted ghost town. As things had begun to fall apart for El Supremo, each new setback only served to fuel his rage and paranoia. He became convinced that his steady and dramatic reversals of fortune could only be the work of a cabal of conspirators and fifth columnists. In his search for scapegoats no one was safe. Hundreds of the country’s leading citizens, including cabinet ministers, prefects, judges, civil servants, military officers, and priests were rounded up and summarily shot. Foreigners were another target. Nearly 200 of them, including several diplomats, were murdered. Finally, Lopez turned on his own family, having his brothers and brothers-in-law put to death for treason.

Caxias lent his considerable organizational talents to the task of setting up a provisional government from what was left of the Paraguayan intelligentsia. He returned to Rio de Janeiro on January 24 and was replaced by Count d’Eu, the 26-year-old son-in-law of the Brazilian emperor. After spending nearly a year resting and reprovisioning the army, d’Eu prepared to reinvade Paraguay and pursue Lopez until he was either captured or destroyed. Lopez, for his part, fled into Azcurra Heights in the jungle hinterland of the country and set up a new capital in the tiny hamlet of Piribebuy. There, surrounded by a retinue of diehard sycophants, he held court protected by a new “army” of women and young boys, most of whom had been shanghaied at gunpoint.

Catching Up With Lopez

That summer, tipped off as to Lopez’s whereabouts, d’Eu crossed the border with 27,000 fresh, combat ready troops and moved in for the kill. On August 11, they surrounded Piribebuy and proceeded to subject the inhabitants to a general bombardment. At 8 am the following day, the task force began making its way up the heights. The Paraguayan defenders opened fire, but they soon ran out of ammunition and had to resort to throwing stones at their attackers. By noon, the Allied army entered Piribebuy over the lifeless bodies of 700 soldiers. D’Eu and his army had killed them all.

All but Lopez. Once again, he had used the destruction of women and children to cover his escape. This time he headed northeast toward Bolivia, one of the few countries in South America that was not at war with him. As El Supremo and a cohort of loyalists made their way into the rain forest, the rear guard charged with covering his retreat was quickly mowed down by d’Eu and the army of avenging nations. On March 1, 1870, the Allies finally caught up with Lopez as he was preparing to cross the Aquidaban River, not far from the Bolivian border. While his henchmen died in a last stand on the banks of the river, Lopez, true to form, met his ignoble end in the water. Wounded by a lance, he thrashed into the shallows, where a bullet smashed into the back of his head as he tried to swim across the river.

In the end, Lopez’s five-year war completely ravaged his own country. Various statistics place the death count as high as 1.2 million—or 90 percent of the prewar population of Paraguay. Other estimates reduce the death toll to 300,000. Only 28,000 adult males survived the conflagration. Whatever the exact numbers, it is inarguable that El Supremo’s misguided war was proportionally one of the costliest conflicts in history, and one from which the hard-pressed nation of Paraguay has yet to fully recover.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments