By Kelly Bell

April 1, 1945, was Easter Sunday and April Fool’s Day. It was also the day the U.S. Army and Marine Corps launched Operation Iceberg, their massive amphibious assault on the Japanese island of Okinawa. Private First Class L.B. Bell was an artilleryman with the Marine 2nd Division, and at dawn he and his buddies were waiting in the chow line for their breakfast before clambering into the landing craft bobbing beside their troop transport.

He later remembered his first acquaintance with the kamikaze, Japanese suicide pilots bent on crashing their aircraft into U.S. Navy ships to sink or disable them. The suicide pilots in had been named in reference to a “Divine Wind” that had destroyed an invasion fleet centuries earlier and saved Japan from conquest. These modern kamikaze, it was hoped, could do the same.

Bell remembered, “The Zero came in on a shallow dive and hit the water approximately 200 yards shy of our LST, skipped over us, and hit a troop transport about 300 yards past, severely damaging it and killing a number of Marines.”

Operation Ten-Go: The Defense of Okinawa

By the spring of 1945, the Rykuyu Islands, the largest of which is Okinawa, were Japan’s last line of defense between its home islands and the inexorably advancing Allied fleets encircling the shrinking Imperial domain. However, Emperor Hirohito’s military commanders were not quite finished dishing out destruction.

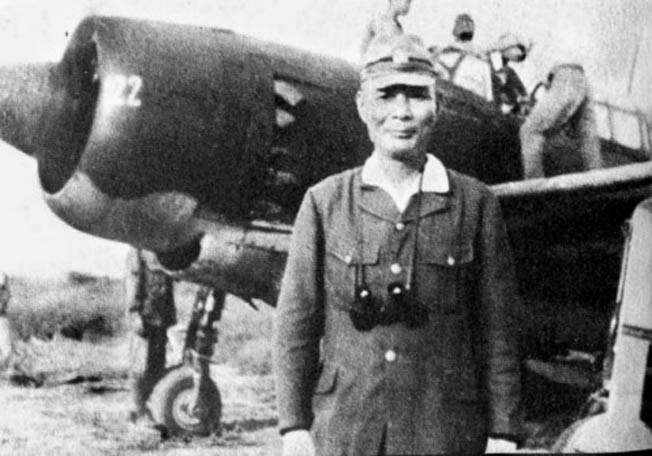

The previous October in Tokyo, Rear Admiral Takajiro Ohnishi, commander of the Ministry of Munitions Naval Aviation Division, had been assigned command of the First Air Fleet, then based in the Philippines. After arriving in Manila to assume his new post he began campaigning for what he correctly believed was his military’s last hope of inflicting substantial damage on the encroaching Allies.

A strong believer in the pseudo-religious Bushido cult with its accompanying code of conduct, he regarded the 1871 abolition of the samurai caste a serious miscarriage of Japanese culture and something to be defied. He and a few of his like-minded comrades devised a lethal new addition to their country’s dwindling arsenal. Suicide aircraft and boats seemed the last hope of seriously challenging the growing might of American arms. What could be more lethal that a bomb-packed craft whose guidance system was an endlessly calculating and fanatical human brain? Not only would the kamikaze pack a pulverizing wallop, but such an honorable loss of life was well suited to a philosophy that glorified self-sacrifice.

Ohnishi and his supporters had to argue their point long and convincingly to overcome considerable opposition from more conventionalminded commanders. Eventually, they won their case when Admiral Soemu Toyoda, commander of the Combined Fleet, had to abandon his anti-kamikaze position when asked what alternative existed besides surrender. He had no answer, and formations of suicide planes and their pilots were soon bound for the empire’s forward outposts.

The Rykuyus were a rich prize. Should they fall, the Allies would have a stranglehold on Japanese supply lines and a base for heavy bomber raids against Japan’s major cities and military installations. Only 340 miles from the home islands, Okinawa had to be held at all costs. If Tokyo kept refusing to surrender, the Rykuyus would also serve well as a staging point for a potential invasion of the home islands. The Japanese realized Okinawa was bound to be the Allies’ next target, but the Americans and British never dreamed of the ghastly reception awaiting them on, over, and off the island.

Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, commander of the Fifth Air Fleet, was given tactical responsibility for Okinawa’s defense, which was codenamed Operation Ten-Go. Ugaki was dismayed to learn his suicide attackers were to concentrate on attacks against Allied supply and troop ships. In earlier campaigns he had witnessed the devastation wrought by U.S. carrier-based warplanes. He lobbied hard and long to have priorities changed to attacks on aircraft carriers, but his superiors ignored his counsel. They did give the carriers equal attention to the supply fleet, but events would prove Ugaki’s fear of the Allied flattops was justified. With attacks divided between the carriers and supply fleet, the kamikazes were spread too thinly, and American carrier aircraft shot Japanese planes down in great numbers.

The CAP: Defending From Kamikaze Attacks

On March 24, the Americans attacked the Kerama Islands, 15 miles southwest of Okinawa. The move surprised the Japanese and distracted Ugaki and his commanders, who were surprised a second time when U.S. Task Force 58 set its planes on the airfields and harbors of Okinawa. Most of the Japanese aircraft available were either designated as kamikaze or engaged in the defense of Okinawa itself. The Keramas were secured on the 26th.

This was also the day the first kamikazes participated in the Okinawa campaign, but their scattered strikes inflicted little damage. The suicide squadrons were still assembling and not yet ready to seriously challenge these earlier-than-expected invaders. Furthermore, the initial attacks tipped off the Allies that there might be serious suicide opposition to Operation Iceberg, so they began making preparations. However, there was not enough time to adequately prepare the large ring of radar stations and specially prepared antiaircraft destroyers manned by fighter detection units to vector combat air patrol (CAP) fighters to Japanese targets. The anti-kamikaze defenses were complicated, especially in overlapping sectors. They also proved rather ineffective against night attacks because the CAP pilots had trouble seeing their targets even when vectoring was accurate.

Exactly 24 hours before the landings were to commence, the defenders almost pulled off a major coup when a solitary kamikaze penetrated all the defenses and crashed into the Allied flagship, the cruiser USS Indianapolis. Admiral Raymond Spruance, overall Allied naval commander, was aboard when the kamikaze struck but was not injured.

Because of their thick, heavy armor plating British carriers were unable to carry as many planes as their American counterparts with their wooden decks, but off Okinawa this added protection proved a fair swap. As the landings were getting underway on April 1, four Mitsubishi Zeros on a flight out of Formosa targeted the British carrier HMS Indefatigable. The screening CAP flamed three, but the fourth scored a direct hit, only to crumple harmlessly on Indefatigable’s three-inch-thick steel shield.

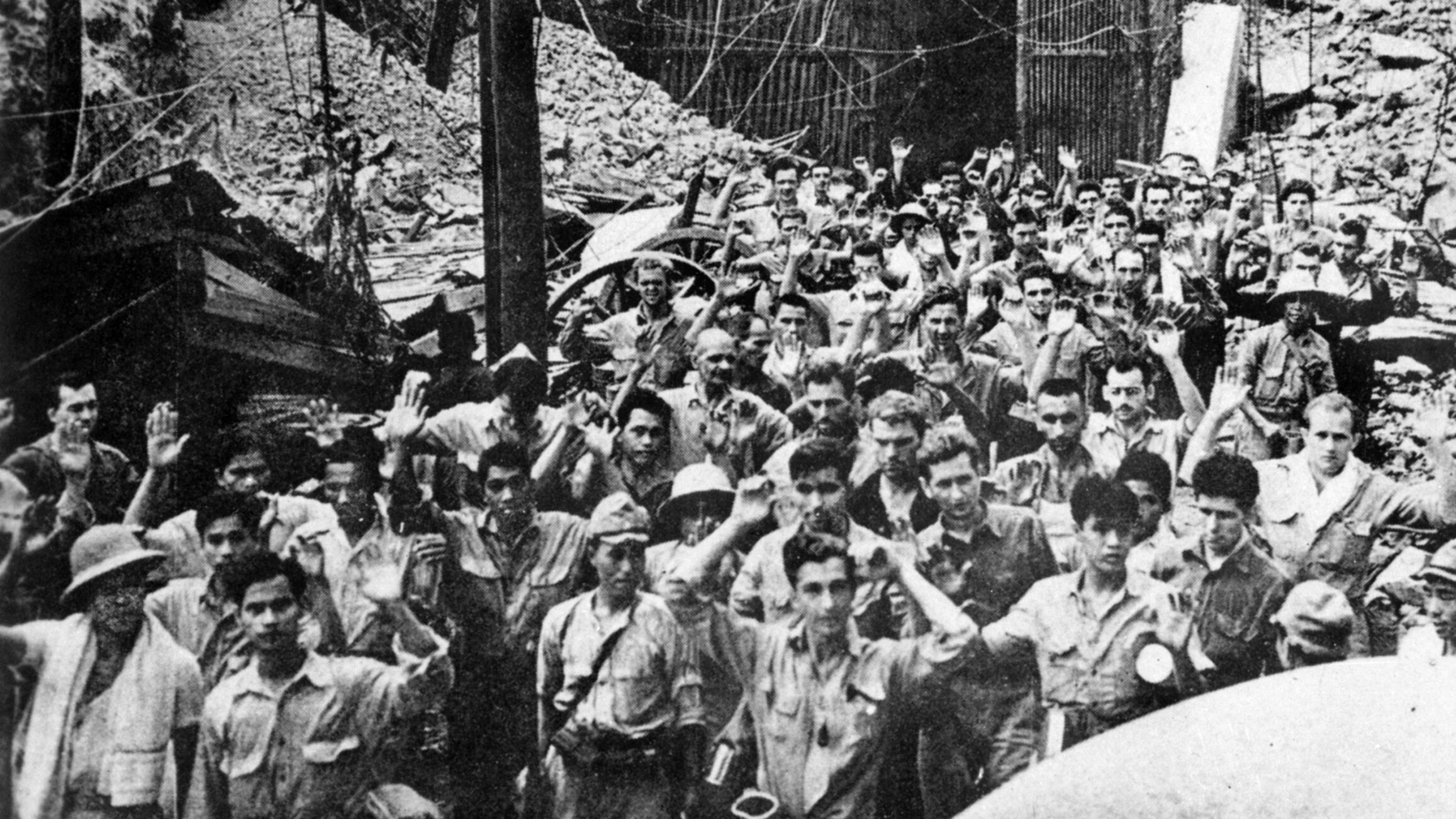

As the cloudless Easter Sunday dawned, other GIs and Marines saw repeats of the kamikaze attack recounted by Pfc. Bell. Many kamikazes either missed their targets or fell easy prey to the CAP and shipboard antiaircraft gunners. This was because nearly all the Japanese one-way pilots were half-trained adolescents. Many had never before flown solo or landed a plane. The empire’s few remaining veteran airmen were far too valuable to expend in suicide attacks, but enough of the rookies were getting through to make a blazing contribution.

Kamikazes reached the battleship USS West Virginia and the destroyer USS Adams on the first day, drydocking Adams for the rest of the war. That night the Japanese launched what they thought would be a surprise attack, sending multiple formations of death divers. Radar detected the approaching flights, however, and alerted a force of Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters that were modified for night fighting. These interceptors ranged destructively through the inexperienced attackers before they could reach Okinawa, downing nearly all of them. It was a brief respite.

A 700-Aircraft Suicide Attack

As the invasion expanded so did the magnitude of the kamikaze attacks. On the afternoon of April 3, a diving Zero grazed the carrier USS Wake Island and inflicted sufficient damage to force her to withdraw to Guam for repairs. That same day a Shinyo suicide boat blew up a landing craft filled with Marines. Then, on April 5, Ugaki was ready to deploy his entire kamikaze fleet.

He code-named the first major offensive Kikusui 1. It was a massive flotilla of more than 700 suicide and conventional aircraft, and on the afternoon of April 5 it fell upon the Allied fleet in numbers that overwhelmed its defenses. The Japanese tried unsuccessfully to use chaff, strips of aluminum dropped from aircraft, to blind the American radar, and carrier-based planes from Task Force 58 met the attackers before they reached the picket ring of radar destroyers. Although these initial Hellcat pilots shot down more than 200 planes and another 200 fell to later arriving interceptors and antiaircraft fire, 180 planes penetrated the American defenses from 3 pm to 7 pm.

The inexperience of the Japanese airmen again was evident as the vast majority of them missed their targets. Only two cargo ships and one landing craft were sunk, but one Japanese plane crashed into the carrier HMS Illustrious just below her waterline, inflicting considerable damage that her crew somehow overlooked until much later in the campaign.

Unwittingly, Japanese officers had aided the defenders by ordering their pilots to attack the first enemy vessels they encountered. The logic here was that by doing so the suicide planes would not be airborne as long, giving the Allies less time to shoot them down. This strategy backfired when, repeatedly, pilots plunged into destroyers that already were severely damaged or dead in the water, and thus essentially worthless targets.

Although the attacks of April 5 knocked out radar destroyers Bush and Calhoun, they also sank the crippled and nonparticipating destroyers Emmons, Newcomb, Leutze, Morris, and Witter while overlooking or ignoring targets of much greater value. The U.S. invasion of Okinawa might have stalled if the troops ran low on supplies, but the neophyte suicide pilots rarely made it to the inner battle zone. American supply ships continued to deliver arms, ammunition, medical provisions, food, and reinforcements while the Imperial defenders ashore were steadily depleted.

Sinking the Yamato

On April 7, the Imperial Japanese Navy sent its super battleship Yamato on an ambitious mission to Okinawa. With just enough fuel for a one-way voyage, the 70,000-ton warship was to be used as bait to lure the Allies’ carriers out to sea where they not only would be more vulnerable to kamikaze attack but too far from Okinawa to support the ground forces fighting there. When the kamikaze formations appeared above the American carriers, Yamato would dash full speed for Okinawa, beach herself in shallow water so she could not be sunk, and then use her 18-inch guns to shell the American-held sector.

This tactic failed when the carrier captains saw through the ruse and only sortied far enough out to sea for their aircraft to be in range of the gargantuan battleship. American torpedo planes and dive-bombers sank Yamato while she was still in deep water. The entire, massive invasion fleet then turned its attention back to Okinawa.

Kikusui 2: Debut of the Ohka Manned Missile

With dependable air support and a steady flow of supplies, U.S. ground forces captured Yontan airfield on Okinawa. Marine Air Group 33 immediately arrived with a complement of 82 Chance Vought F4U Corsair fighters to bolster ground support and strengthen the anti-kamikaze screen.

On April 10, violent thunderstorms grounded all planes on both sides, but the next day the sun came out. Ugaki’s pilots managed a major coup when two Yokosuka Judy divebombers survived the CAP and dense antiaircraft fire and hit the carrier USS Enterprise just below the waterline. Working frantically, damage control parties managed to seal off the holed section of hull before the flattop capsized, but she had to withdraw.

Kikusui 2 kicked off on the 12th when 150 fighters escorted 185 suicide aircraft, including nine of the newly developed Ohka manned missiles, fell upon the Allied armada. Still going after the first targets they encountered, they decimated the destroyers of Radar Stations 1, 2, and 14. The first Ohka ever to strike a hostile ship nearly cut the destroyer USS Mannert L. Abele in two, sinking her with 79 of her crewmen in a twinkling.

The kamikazes had crippled or sunk seven destroyers by 2:30 pm, and that evening late-arriving planes hit the battleships Idaho and Tennessee. Yet, Ugaki still failed to realize his strategy was faulty as his pilots continued to expend themselves on the outer perimeter while ignoring plum targets closer to shore.

Only 11 Carriers Left

April 12 was also the day the Americans learned of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After spending 12 years in the White House, Roosevelt was the only president many of the young men fighting on Okinawa could remember. Disheartened that their chief had not lived to see the final victory, the Army and Marine troops fought with gusto the next day when the Japanese launched a violent counteroffensive. The Japanese land and air forces failed to coordinate their actions, however, as the ground attack began between aerial offensives, and no kamikazes or conventional warplanes came to the support of the ground troops.

Kikusui 3 kicked off April 16 and deployed just 300 conventional and kamikaze planes reinforced by a flight from Formosa. When these planes descended on Task Force 58 most of the pilots repeated their predecessors’ errors, wasting themselves on low-priority targets. One of them did manage to strike the carrier USS Intrepid and punch through her deck. The plane’s bomb exploded in the hangar and ignited a raging conflagration that killed 10 men and sent Intrepid off for repairs that were not completed until after Japan’s surrender.

Despite their imprudent target selection, the kamikazes had now left the Allies with just 11 carriers to support the Okinawa campaign. Fearing further attrition, Spruance dispersed his precious flattops so they would not present a conspicuous, collective objective. For the time being no more kamikazes appeared.

After using up more than 800 planes in suicide attacks since the first of the month, Ugaki and Ohnishi had to wait for additional aircraft to be delivered before they could resume more than occasional attacks. This gave the U.S. troops ashore a crucial respite they used to overrun the adjacent island of Ie Shima and Okinawa’s northern sector. They wasted no time installing radar posts in both areas.

The next major kamikaze flight arrived just before dusk on April 22. After a six-day lapse in attacks, the Japanese hoped this one, launched from airfields on Kyushu and Formosa, would take the Allies by surprise, but the new radar sets detected the raiders just in time for a squadron of Corsairs to rise to the defense. The Marines shot down 34 planes and dispersed most of the rest. A minesweeper and landing craft were lost along with 60 men.

With just 115 planes, Kikusui 4 was small, but it finally targeted the invasion forces’ vital transport and supply elements. The freighter Canada Victory was sunk, the merchantman Rathburn was crippled, and the destroyer Ralph Talbot sunk. The following afternoon a large flight attacked the radar installations but was decimated when Station 2 vectored in Corsairs that scattered the suicide planes before they reached the perimeter.

Starting at 10 pm a lone kamikaze spent 15 minutes circling the floodlit and red-cross-emblazoned hospital ship Comfort, looking her over and coming to an informed decision before pulling up and heartlessly diving into her. Thirty died in this wanton act of murder. About half were homebound wounded soldiers, but the pilot also killed a whole surgical team and an additional six Army nurses.

On April 30, a ragged pack of kamikazes targeted the minelayer USS Terror. Enough got through to cripple the vessel and kill 48 of her sailors while wounding another 173. It was one of the campaign’s most devastating attacks, bringing April’s total to 115 Allied ships sunk. Another 61 had been compelled to leave for repairs. Most of these needed such extensive work that they were forced to retire to distant Pearl Harbor or San Francisco to find adequate repair facilities.

An Overextended CAP

The Japanese had wrought this destruction at a cost of slightly more than 1,000 novice pilots who, considering their extremely limited qualifications, could not have been used for any other purpose. Back in Tokyo news of this success essentially killed all remaining opposition to the suicide attacks. Okinawa was turning out to be much more expensive for the Allies than either side had anticipated. Still, the forces of liberation doggedly kept up the pressure.

As daylight was fading on May 3, Kikusui 5 roared in from Formosa immediately after the Marine CAP had left for the evening. Their marks were Radar Stations 9 and 10 west of Okinawa. The outposts’ crews, not expecting an attack so late in the day, had just shut down their sets when the yellow-painted warplanes dove on them. The attackers sank the destroyer Little, left her sister ship Aaron Ward dead in the water, and killed or wounded 241 sailors. A tug towed Aaron Ward to an anchorage Spruance had set aside off Kerama for crippled ships. It was crowded with vessels awaiting work crews that would cut them up for scrap.

May 1 dawned with an attack on Radar Station 12 that sank the destroyer Luce with 149 of her men. Minutes later the overextended CAP could not save the destroyer Morrison. Two bomb-carrying Zeros crashed into her from 12 o’clock high, destroying her engines and boilers. Before most of the men below decks could get topside, two old Kawanishi floatplanes out of Kyushu plowed into her hull. Morrison’s after turret exploded like a volcano, disintegrating her stern and sending her under with 159 crewmen. Bobbing in the debris-cluttered sea, 103 of her horrified survivors watched helplessly as three Zeros slammed into their sister ship Ingraham, transforming her into a floating bonfire. A landing craft tried to tow her out to sea, but yet another suicide plane hit and sank it.

The weather was helping the Japanese because CAP pilots and antiaircraft gunners could not see through a thick haze that had formed just before dawn. The kamikaze pilots, however, were having no trouble picking out the highly visible white wakes of their frantically maneuvering targets. A large number of planes then took aim at a group of minesweepers north of Kerama. While the available interceptors were distracted by this raid, a single unnoticed Nakajima Oscar flew at treetop level over Okinawa, pulled up as it crossed the beach and plunged into the cruiser Birmingham at 8:41 am. Penetrating the deck, its bomb detonated deep inside the ship, causing flooding and fires that killed 51 men. Birmingham limped out of action.

By the morning of May 4, this latest suicide offensive had sunk or crippled another 12 ships. Allied naval casualties included 420 dead or missing and another 470 wounded.

That evening the Royal Navy felt the kamikazes’ sting as Formosa-based planes attacked the carriers Indomitable and Formidable southwest of Okinawa. Formidable’s radar operators mistook an approaching Zero for a friendly plane and allowed its pilot to take careful aim. Using the favored tactic of pulling up at the last moment, he went into a dive, revved his engine to full power, and crashed into the flight deck at extreme speed. The armor plating was hardly dented, but the impact dislodged a large slab of steel that had been improperly welded to the deck’s underside. It fell onto and ruptured the carrier’s central boiler, reducing her speed to 18 knots. The Zero’s bomb exploded topside, killing eight men and destroying 12 of the flattop’s limited store of fighters. Kikusui 5 was over. It had bled the Allies badly, but at great cost to the Japanese.

Kikusui 6: Striking the USS Bunker Hill

The Japanese had hoped the violent suicide attacks offshore would assist their army’s latest offensive by cutting into the Americans’ supply lifeline to their ground forces, but this strategy overlooked the impact of the Allies’ pulverizing naval firepower. Shelling from their warships broke the Japanese offensive and fatally depleted the defenders’ manpower reserves. Against this weakened defense, the U.S. Marines and Army began to break out of Okinawa’s southern sector.

For a while the Japanese were able to launch only sporadic suicide attacks. On May 8, both sides received word of Germany’s unconditional surrender. This was expected but very welcome news for the Allies, but the Japanese seemed to take it as a signal to display their defiance.

On the 11th a typhoon of kamikazes crowded the sky as Kikusui 6 arrived. The first victims were the destroyers Hugh W. Hadley and Evans, both of which were reduced to drifting wreckage. Just after 10 am a Zero and a Judy dive-bomber evaded the CAP by approaching through low cloud cover and hit the carrier USS Bunker Hill. The Zero impacted first and set the after deck ablaze. The Judy crashed onto the same spot and tore a huge hole in the weakened deck. The Judy’s bomb came loose and tumbled into the ship’s interior before exploding.

For the next five hours a raging conflagration enveloped the carrier’s stern, killing 404 men, wounding another 256, and very nearly sinking the vessel. The grievously hurt Bunker Hill would not have survived another direct hit, but frantic Corsair and Hellcat pilots knocked down every other enemy plane that approached until darkness halted the attacks.

The next day the Japanese lulled the Allies into a false sense of security by not appearing at all … until sunset. Then two kamikazes crashed into the battleship New Mexico and killed 54 of her crew.

Air Assault on Kyushu

By this point U.S. ground forces had captured enough airstrips on Okinawa for land-based warplanes to deploy for CAP service and infantry support. This enabled the carriers to depart for Kyushu to assault the airfields of the 5th Air Fleet. Despite losing 130 of his aircraft both on the ground and in the air in these strikes, Ugaki quickly retaliated. On the 14th, Enterprise returned after having her earlier damage repaired and was immediately set upon by 24 kamikazes. Just one plane survived the antiaircraft fire and CAP, but it scored a direct hit on the carrier’s essential elevator, knocking it out and igniting a damaging fire. Enterprise again turned for the drydocks.

Still, the aerial attacks on Ugaki’s airfields temporarily took the edge off the suicide offensive. Scattered attacks resumed on the 17th. Corporal Fred Reese, a rifleman in the 2nd Marine Division, later recalled that a Zero charged his LST so low it was “skimming the waves,” but the coxswain yanked the craft around so that only the plane’s wing struck it, inflicting little damage.

On the 20th, 40 Japanese aimed for the supply fleet moored just off Okinawa’s west coast but again displayed poor target selection. They dove on the encircling destroyers, crippling Chase, Register, and Thatcher. One pilot crashed his Zero into the drifting hulk of an abandoned LST.

The Allies again targeted the sprawling Kyushu airfields on May 23, this time using a just-arrived squadron of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. Renowned and dreaded for their pulverizing .50-caliber firepower, these fighters destroyed 84 parked aircraft, including a number of the twin-engine Betty bombers used to launch the Ohka rockets. This destructive preemptive strike left Ugaki with just 65 aircraft for Kikusui 7.

The small number of available planes coupled with violent thunderstorms to severely limit the damage done by the next attacks. Just eight ships, none larger than a destroyer, were damaged, and none sunk. Ugaki tried to achieve the element of surprise by sending the next offensive immediately, but this wave, too, flew into dirty weather. Two Aichi Val divebombers did manage to strike the destroyer Braine off Ie Shima, setting her afire and killing 66 sailors, and a lone kamikaze crashed into the destroyer Forrest, killing five men and leaving her dead in the water.

The following dawn a suicide flight of Nakajima Irving night fighters and Yokosuka Frances bombers (all twin-engine planes) attacked Radar Station 15, virtually disintegrating the destroyer Drexler and killing 158 of her crew. Two hours later another formation made a potentially crippling assault on the Allies’ main supply anchorage but because of poor aim sank only one freighter, Josiah Snelling, and slightly damaged four other merchantmen.

Operation Ten-Go’s Final Attack

The final attack of Kikusui 8 came just after midnight when a twin-engine plane spent 15 minutes slowly circling the destroyer Shubrick, lulling her crew into assuming it was a reconnaissance plane. The pilot suddenly turned and plowed into the stern just over the engine room, ripping a 30-foot hole in her deck and hull. Surprisingly, only 32 men were killed, but damage control could not stanch the gaping wound and she began to settle in the water. She foundered just after the last of her crew were removed. Shubrick was one of the last victims of Operation Ten-Go.

Although the kamikazes would keep coming through the first three weeks of June, the Allies declared Okinawa secure on the 18th. The last major campaign of World War II ground to a conclusion as Ugaki, Ohnishi, and their fellow commanders began hoarding their remaining warplanes and approximately 5,000 pilots in training for the anticipated amphibious invasion of Japan’s home islands. Then the Americans used a horrific new martial technology to immolate the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A cease-fire went into effect August 16, 1945.

This was also the day Ugaki practiced what he had been preaching, flying a Zero in a final attack on Task Force 58. He never made it. An American flying a Corsair shot him down before he reached the fleet. Ohnishi followed suit. On that morning he wrote a final message to his country’s young people: “You are the treasure of the nation. With all the fervor of the special attackers, strive for the welfare of Japan and for peace throughout the world.”

Perhaps he did not notice the incongruity of an adjuration for peace coming from a warlord who had sent a multitude of young men to flaming death and then committed suicide himself, leaving the next generation to rebuild their ravaged islands without him. He likely saw no place for himself there in peacetime.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments