By Christopher Miskimon

On the morning of November 6, 1942, a force of 267 Marines took its first steps into the jungle from a landing point at Aola Bay, roughly 30 miles east of the American perimeter on Guadalcanal. The Marines within the perimeter had suffered long and hard to establish that perimeter around Henderson Field, the airstrip used to launch attacks against Japanese forces in the area and defend the Marine position. Still, outside the secure area Japanese troops moved at will. While the dreadful battles of previous weeks had drained them, they were still a force to be reckoned with, and the Japanese high command was yet trying to reinforce and supply them.

The men leaving Aola Bay were Marine Raiders, a new type of Marine unit, led by Lt. Col. Evans Carlson. They had trained using new and controversial concepts pioneered by Carlson himself. Now those ideas were being put to the test. The Raiders’ orders came from Marine Maj. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift, commanding the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal. An aircraft dropped the order to Carlson on November 5. The Raiders were to conduct reconnaissance to determine what Japanese forces existed to the east of Henderson Field. Also, they were to engage any Japanese troops fleeing southward into the jungle from Koli Point, where substantial enemy forces had been pinned down by American action.

They were going in practically blind. There was almost no information about the number of enemy soldiers in the area the Raiders were to cover. No one knew where they might be hiding or what routes they were using. It mattered little; in the absence of such information, that was what the Raiders were for. The mission would turn into an epic month-long fight, elevating the reputation of the controversial Raiders to near legendary status even among the elite Marine Corps.

Carlson’s Raiders: Guerrilla Warriors of the Marine Corps

The journey that brought the Raiders to Guadalcanal began in the dark days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Evans Carlson had been calling for the formation of a commando-style unit of Marines to carry out hit-and-run, guerrilla-style missions based on theories of leadership and teamwork he had witnessed in China during the 1930s. While assigned to China, Carlson had observed Mao Tse-tung’s Eighth Route Army and was impressed by its teamwork and ethics, which he felt would be compatible with those of a democratic society based on justice and equality, namely the United States. In the Communist Chinese Army, Carlson observed, leaders explained to their troops the reasons why they were fighting and encouraged their soldiers to speak out with any ideas or criticisms that could make the army more effective. Carlson thought this would mesh perfectly into the American military since Americans did not have a culture of blind obedience to authority and took pride in thinking for themselves. In Carlson’s mind these concepts could be blended to make troops who would use their initiative in support of overall goals since they would be informed of the reasons and goals of their missions.

While a few were supportive of his theories, many Marine officers felt Carlson’s ideas went against the discipline and hierarchy a military organization needed. They considered Carlson himself foolish at best and at worst a communist sympathizer.

Carlson had an ally, however, in the Roosevelt family. The Marine officer had been part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s security guard detachment in the early 1930s and developed a sort of friendship with the commander-in-chief. Carlson also took the president’s son, James Roosevelt, under his wing when the young man obtained a Marine commission shortly before the war. For some this made Carlson even less trustworthy because he had a direct link to the president that circumvented the regular chain of command.

However it occurred, Carlson did get his battalion, which began forming in February 1942 near San Diego. Marines started hearing of an unconventional officer forming a new type of unit that would see action sooner rather than later. The eager and adventurous began filtering in. They were put through a rigorous interview process which asked them if they could “starve and suffer and go without food and sleep.” Many recalled being asked if they thought they could cut an enemy’s throat or strangle him. Those who were indecisive or hesitant were sent away.

Those who were accepted were sent to train at Jacques Farm south of Camp Elliott, California, part of what is now Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. Carlson gathered his new recruits and explained to them why they were there and what they were fighting for. He also promised them nothing but “rice, raisins, and Japanese” and “danger, despair and death.” The men were also introduced to the Raiders’ motto “Gung Ho!” from the Chinese term for working together.

The new Raiders did indeed learn to work together. There were no facilities at Jacques Farm; the Marines built the camp themselves. For six weeks they ran, hiked, swam, scaled cliffs, and learned to use their various weapons, from hands and feet to explosives. Eventually they could move seven miles an hour in full equipment, and 70-mile hikes took place weekly. Before long the Raiders were tough and confident. Carlson also indoctrinated the men with his notions of equality. Officers lived in the same conditions as their Marines, ate the same food, and got few of the perks officers were accustomed to. There were frequent meetings to discuss training and current events. Enlisted men were encouraged to speak up, even with criticisms. Despite the fears of more conventionally minded officers, the Raiders quickly became a cohesive, skilled unit. Within a few months they were ready for active service.

Makin: First Combat For the Marine Corps Raiders

The first operation for the Raiders came on August 17-18, 1942, on Makin Island, nearly 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii. A small Japanese garrison had occupied the island with plans to construct a seaplane base. A decision was made to raid the island; while it was a small, non-vital outpost, such a strike would boost morale at home, still uncertain despite the victory at Midway two months earlier.

Carlson and his executive officer, Major James Roosevelt, led two companies of Raiders in the attack. They traveled in a pair of submarines to the island and planned to go ashore in rubber boats. Once ashore they would kill or capture the garrison and destroy anything of military value before returning to the subs for the trip back to Hawaii. It was thought to be a perfect mission for a fast, hard-hitting commando group.

In the event, the raid was completed but there were numerous difficulties. The surf was extremely rough; the boats’ motors were quickly waterlogged, and the Marines had to paddle to shore in the pitching waves, losing weapons and equipment along the way. Once ashore, the enemy garrison acted quickly and boldly in its defense, resulting in stiff fighting. The Raiders fought bravely, but being new to actual combat the fog of war set in and there were problems in communication and some later decried a lack of aggressiveness. When the time came to return to the subs the surf again proved an enormous obstacle to the tired Raiders, delaying their rendezvous with the vessels until the next day. Controversy came later when claims Carlson considered surrendering were brought forward; the debate over this issue continued for decades.

Still, the Marines did considerable damage on the island and killed much of the garrison. Upon their return they were greeted as heroes, and much was made of Carlson and his methods in the press. This further rankled some of Carlson’s detractors, and some of the difficulties, known only to members of the high command such as Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander-in-chief Pacific Ocean Areas, were used to quietly criticize the Raider unit and concept.

“Behind Enemy Lines” on Guadalcanal

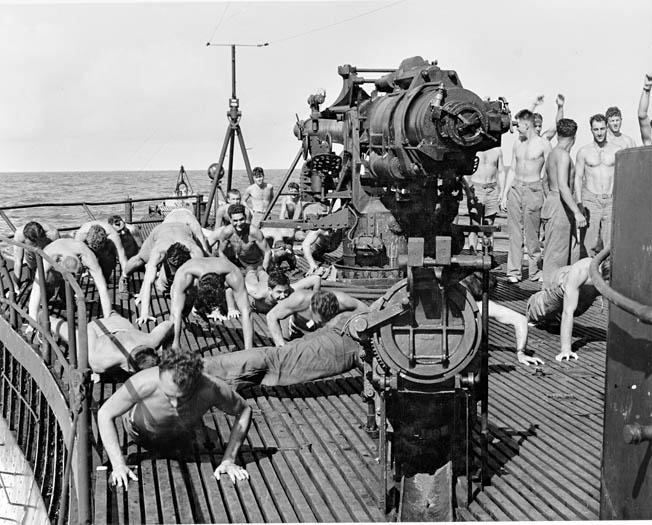

Even Carlson longed for another chance to prove his unit and his methods. That opportunity would come at Guadalcanal. When General Vandegrift wanted someone to operate outside the Marine perimeter, essentially “behind enemy lines,” the Raiders seemed to fit the bill. It was what Carlson longed for. They would operate essentially on their own, patrolling, hitting the enemy, and then fading into the jungle to strike again elsewhere. By this time the Raiders had moved to a camp on the island of Espiritu Santo, where Carlson selected two of his companies to move to Guadalcanal to begin operations with the idea that other companies would follow. Captain Harold Throneson’s C Company and E Company under Captain Richard Washburn were chosen. On October 31 they went aboard the converted destroyer transport USS Manley for the journey to embattled Guadalcanal. Along the way a storm struck, the little ship was tossed about over and through the powerful waves; almost every Raider became seasick.

Finally at 0530 on November 4, Manley arrived in Aola Bay, and the Marines disgorged from the ship in Higgins boats. Approaching the shore they could see the lush jungle that grew right up against the beach. It was beautiful from a distance, but the Marines would shortly learn the jungle’s beauty was also fraught with danger, sickness, and hardship unlike anything they had seen before. They also worried about the enemy. Did they hide just inside the green foliage, were they waiting even now to pour deadly machine-gun fire and mortar bombs into the fragile landing craft?

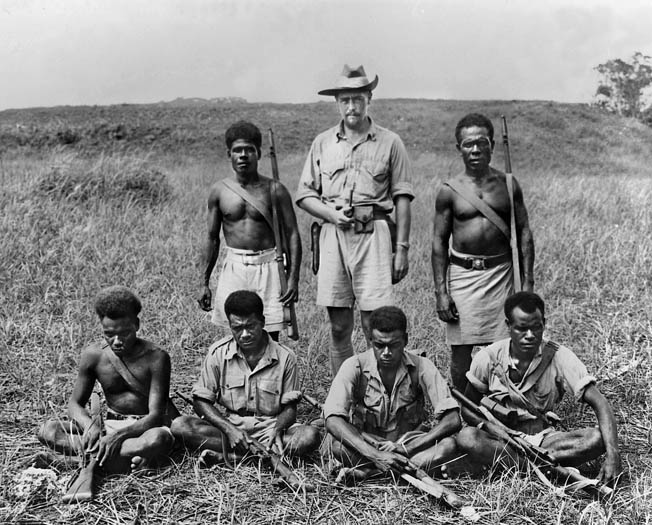

Luckily the Japanese were not there to greet them. Instead, two Allied personnel stood waiting for them near a bonfire lit as a prearranged signal to guide the Marines to shore. They were Martin Clemens, a British citizen responsible for organizing the native scouts in the Solomon Islands, and Australian intelligence officer Major John Mather. As they watched, the Raiders exited the boats and came ashore, traveling rather lightly in terms of equipment and comfort items but festooned with weaponry. Each Marine rifle squad was divided into fire teams of three men, one with an M1 rifle, one with a Thompson submachine gun, and the third carrying a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). Added to this mix was a liberal dose of shotguns and .45-caliber pistols. Such heavy firepower would prove an advantage in the jungle. Clemens looked at the nearest Marine and said, “I say, what kept you chaps?”

The Raiders spread out and formed a perimeter. There was little sleep their first night in the jungle; they had not yet learned to distinguish the normal sounds of the jungle from those of a creeping enemy. The next morning Vandegrift’s orders were airdropped, and Carlson finalized his plan. Mather and Clemens would take charge of 150 native scouts and bearers; the scouts would lead the Raiders on their patrol route while the bearers would carry fresh supplies from designated points along the coast. Carlson left a small group at Aola to deliver those supplies via Higgins boats. Some supplies would be air dropped as well.

The Raider companies would move gradually west toward Henderson Field. They would scout through areas of reported Japanese presence, stopping at villages along the way. Wherever possible they would harass and hurt the enemy to ease the strain on the Marines at Henderson. It was the chance Carlson had been waiting for. He was about to prove his Raiders worthy.

First Clash on Guadalcanal

On the morning of the 6th, the Raiders walked into the jungle, native scouts at the lead. The trails were so narrow they had to move single file through the sweltering heat, sweat running off them in rivulets. Swamps and streams slowed them and Liana vines, their long thin shapes covered with tiny barbs, cut at uniform cloth and skin alike. The Raiders’ worst enemy that first day was the jungle itself; they made only five miles. When the Marines stopped for the day the pouring rain made no difference. They fell asleep anyway. Still, there was tension. At night nervous sentries fired shots at imagined enemies.

The next day they sped up their pace at Carlson’s urging. The older Marine moved with the point squad to set an example. The day started out the same: heat, rivers to cross, and more foliage to fight. Soon they arrived at Reko village on the banks of the Bokokimbo River. It was devoid of inhabitants, but Japanese cigarette wrappers and ration boxes were strewn over the ground. The main body of Raiders was still several hours from the village, so Carlson posted sentries and let the rest bathe and wash their sweat-encrusted uniforms.

At first it was an almost peaceful scene, but the Raiders were warned the situation was about to turn deadly when the birds in the area suddenly went silent. Scant seconds later rifle shots shattered the quiet, and the Marines scrambled to action. They waded the neck-deep waters, weapons held over their heads, as bullet impacts raised plumes around them. The fire was thankfully inaccurate, and the entire group made it to the other side. One Marine, Pfc. Warren Alger, jumped toward cover when the shooting started but landed in a tangled web of Liana vines that left him hanging three feet above the jungle floor. Unable to free himself, he had to wait until his fellow Raiders helped him.

Other Marines began searching for the Japanese, among them Private Darrell Loveland. Soon they came to a small clearing. In it were 10 Japanese soldiers gathered around a dead pig they were in the process of skinning. Perhaps the prospect of a meal was too tempting to the hungry Japanese, but Loveland and his fellow Marines were not going to waste their good luck at catching the enemy unawares. They opened fire, killing two in the first volley and causing the rest to flee. The Raiders gave chase, and Private Lowell Bulger found one of them, wounded, lying in the jungle. He pulled the injured Japanese to the trail. The soldier’s intestines hung grotesquely out of his open stomach, and he soon died. Bulger found a small oilskin envelope sewn into the folds of his uniform. It contained some papers and a bit of money.

Fighting on the Metapona River

Their first fight was over. Carlson moved his Raiders to Binu, a village a few miles west of Reko. They had found no substantial sign of Japanese troops from Binu east to Aola Bay. Now they could concentrate their efforts to the west toward Henderson. Binu was also the last inhabited village along their route. Only the Japanese enemy stood in their path now, and it seemed those enemy would be coming their way. Army and Marine troops had advanced east from Henderson Field against some 1,500 Japanese who had been emplaced northwest of Binu. The intent was to keep them fixed along the coast where they could be destroyed, but two-thirds of the enemy force slipped through the trap into the interior of Guadalcanal to the area Carlson and his Raiders were to cover.

Carlson decided to send his men on a series of patrols toward the River Metapona. This seemed the area most likely for the retiring Japanese to travel through. They would begin the next morning, November 11. The current day, November 10, was the Marine Corps’ birthday. The celebration feast was the normal ration of rice and bacon. Ironically, the following day was Armistice Day, celebrating the end of World War I. By this time C and E Companies had been joined by D Company under Captain Charles McAuliffe and Captain William Schwerin’s F Company. At dawn the Marines were up and ready to move, Carlson moving to each company to give them their instructions for the day. Company B would remain at Binu to act as the battalion reserve, while the other four, C, D, E, and F, would patrol along separate routes to search for the retreating Japanese.

The patrols encountered nothing until 1000 hours, when C Company ran into a determined Japanese defense. Corporal John D. Bennett was leading his men across a field of Kunai grass when an unseen machine gun shattered the air with its hammering. Bennett was killed immediately along with several others while fellow Marine Private Pete Arias and two other survivors hit the dirt. Another fire team under Private Darrell Loveland tried to advance but was also pinned in the field. Small arms fire, mortars, and grenades pelted the Marines. Arias was pinned down only 20 yards from a Japanese machine gun. Fortunately, the enemy could not see him. Other Marines were not so lucky. Private James Van Winkle was hit three times as he tried to get to cover. Captain Throneson radioed Carlson that his company was engaged.

Almost simultaneously mortar bombs began falling on Company E as it crossed a field northeast of Asamana village. Captain Washburn led his Marines into the jungle and out of the mortar fire. He could hear C Company’s fight nearby. Still, C Company seemed to be the unit decisively engaged. Carlson came up with a plan. He ordered Throneson to hold in place, thus fixing the Japanese and drawing their focus to his company. Washburn and E Company were told to move south toward Asamana and hit the enemy force in its rear. Company D under McAuliffe would likewise turn south and hit the Japanese left flank. Schwerin and F Company would come back to Binu and await developments. To ensure C Company could hold, Carlson reinforced it with a platoon from the battalion reserve.

The plan went into motion with one problem. As McAuliffe and his Marines began moving toward C Company, they came under fire themselves. McAuliffe had elected to travel with the point and found himself and one squad cut off from the rest of his company. It was now up to Washburn and his men.

Sending native Jacob Vouza ahead with his scouts, Washburn led his Marines through the jungle along the winding Metapona River toward the furious battle ahead. The scouts reported Asamana village was deserted except for a few Japanese. As the Americans entered the village checking for hidden enemy soldiers, Washburn saw a group of men crossing the river south of the village. At first he thought they were Marines from C Company, but he quickly realized they were Japanese who had no idea the Marines were there. Suspecting the group crossing the river was part of the Japanese main body and the group engaging C Company was a blocking force, Washburn set up his men to defend against flank attacks and gave the order to fire on the group crossing the river.

The Marines tore into their enemy with BARs and chattering .30-caliber machine guns. Pfc. Jesse Vanlandingham recalled, “It was like shooting birds. The guys in the front lines were mowing them down.” Caught in the water, many Japanese troops never even had the chance to fire back. Still, the seasoned enemy veterans reacted quickly, setting up a machine gun of their own on the far bank. It drew Marine fire, but determined Japanese soldiers kept manning it. Each time the shooter was killed, another Japanese would take his place. Finally, several Marines led by Lieutenant Cleland Early crept close enough to throw grenades, silencing the machine gun for good. Checking the position, Early was almost killed when he turned over an enemy body and exposed a grenade the man was holding. Luckily the young Marine only took some fragments in one hand.

“He Knew He Would Die… But He Kept Firing.”

Within a short time the expected counterattack happened, as two Japanese companies moved on Washburn’s flank at 1130 hours. Washburn pulled his company back into the jungle a short distance and radioed a report to Carlson. The Japanese, believing they had repulsed a small enemy patrol, resumed crossing the river; some even paused to bathe. The Marines were not finished yet, though. Washburn reorganized his men and sent two platoons into a new attack while a third moved around to the north for a flank attack of its own.

Having let their guard down, the Japanese were completely surprised, and many were killed in the Marines’ deadly crossfire. As before, however, they recovered quickly and fought back, sending more mortar fire crashing into the American positions. Small attacks and counterattacks went back and forth in the humid, hot jungle. Marine Lieutenant Robert Burnette used his deadly shotgun to kill a Japanese only 10 yards away. Machine guns ripped from both sides, and grenades tore through foliage and human flesh alike. This went on for some six hours until the Marines began running out of ammunition. Now the greater enemy numbers started to tell. Washburn decided to pull back rather than risk being outflanked. The Japanese were slowly surrounding them.

A trail going north through a gully provided the Raiders with a way out. Washburn placed a machine gun at its mouth to cover the retreat then pulled his platoons out one at a time. A young Marine, Private Joseph Auman, manned the gun and lay down covering fire as his Raider brethren escaped the Japanese trap. Before the 20-year-old Marine could make his escape, he was overwhelmed and killed. “He knew he would die,” said Private Lathrop Gay. “But he kept firing.” Auman was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for his sacrifice, which allowed his company to fight again.

Elsewhere, the pinned Captain McAuliffe eventually extracted himself and what remained of the squad from their cut-off position but could not rejoin the rest of the company. Eventually, he led nine Marines back toward Binu, arriving a few hours before a platoon sergeant returned with the rest of the company. Throneson likewise managed to extricate his Raiders from their position with some difficulty and fell back. In the confusion Pete Arias did not get the word to retreat but eventually crawled to safety through the enemy fire.

At Binu Carlson gathered B and F Companies and moved toward the fighting, unsure of exactly what was happening in the confusion. Within an hour he found C Company, disorganized and apparently leaderless, Throneson wandering in a daze. The colonel called for an air strike from Henderson Field, his Raiders indicating the Japanese position with a makeshift arrow formed from Marine t-shirts. Within 10 minutes a half dozen planes roared overhead and dropped their ordnance on the enemy. When Carlson sent scouts into the jungle, however, the Japanese were gone, having withdrawn south. He left the comparatively fresh F Company (with a platoon from Company B attached) to form a defensive line for the night while he took the rest of his weary command back to Binu.

It had been a long and confusing action. Carlson was disappointed in Throneson and McAuliffe’s actions and relieved them a few days later. Still, the Raiders felt they had won the day. The American casualties amounted to 10 dead and 13 wounded. In comparison, 160 Japanese lay dead on the battlefield, 120 killed by Washburn’s company. Carlson promoted him to major for his quick thinking and courage, clearly believing the young officer had retrieved the situation for the Marines.

No Prisoners

The next day they returned to the battlefield to look for remaining pockets of the enemy. Since the Japanese had mostly fled south, time was devoted to finding and burying fallen Americans. While searching the area where Company C had fought, the disfigured, mutilated corpse of Private Owen Barber was found. His face was slashed horribly, and his testicles had been cut off and shoved into his mouth. Another Marine, Pfc. James Clusker, cut off from escape, hid in the Kunai grass that night near the wounded Barber. When the Japanese found the injured man, Clusker had no choice but to hide helplessly in the grass, listening while the hapless Barber was tortured and killed.

The tortured form of Private Barber had a transformative effect on the Raiders. They knew what they could expect if captured, and most resolved not to take prisoners themselves anymore. Two Japanese taken the day before were summarily killed with Carlson’s assent. Some Marines argued that taking prisoners was unfeasible; they could not feed or watch them with their limited resources. Others maintained if they had not killed the Japanese it would have damaged their relations with Jacob Vouza and his scouts, whose families had suffered at Japanese hands. It was brutal war with little quarter given by either side.

The Raiders retook Asamana, recovering the body of Private Auman and finding his machine gun thrown in the river. They decided to occupy the village overnight. In the darkness, Japanese stragglers wandered into the village unaware it was in American hands. Twenty-five of them died that night, victims of both ignorance and Marine rifles.

The next day, November 13, the Raiders fought in and around Asamana. Scouts reported enemy troops to the north, south, and west. In a scene that could have come from a movie, a sentry saw bushes moving toward the Marine positions. Carlson looked for himself and indeed saw what appeared to be vegetation creeping closer. Heavily camouflaged Japanese were sneaking closer, stopping every 100 yards to see if they had been spotted. Letting them close to 100 yards, Carlson coordinated a mass of machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire that crushed the enemy attack and sent the survivors into headlong retreat, trailing blasted bits of flora behind them. Four more attacks were similarly beaten back before the Marines retired to Binu that afternoon. On November 14, Captain Schwerin led a patrol that ambushed 15 Japanese who had stopped to rest and eat, killing them all.

Taking Out Pistol Pete

A change of mission occurred on November 17, when General Vandegrift met with Carlson and ordered him to clear the area around the Nalimbiu and Tenaru Rivers inland from the mouth of the Tenaru. Afterward, he was to find the trail the Japanese were using to move men and matériel eastward. This trail was thought to be behind Mount Austen. Finally, somewhere on Mount Austen hid “Pistol Pete,” enemy artillery that constantly harassed the Marines around Henderson Field.

The Raiders began their new mission the next day. For the next week they found themselves involved in skirmishes, patrols, and firefights mostly in squad- and platoon-sized elements. The Raiders used their tactics of fix-and-flank, and the Japanese tried to do the same. Jungle encounters were usually at close range due to the thick foliage, which provided concealment but little actual protection from bullets and shrapnel. The Marines had a deadly advantage in their semiautomatic M1 rifles, submachine guns, and BARs. Squad for squad the Americans could throw a much heavier volume of fire at their opponents, who had bolt-action rifles and relatively few automatic arms. The Raiders also issued shotguns liberally; many of Carlson’s men had used them to hunt back home, and they proved excellent for quick, short-range work.

As the patrol wore on, the Raiders found disease to be a much more implacable foe than the Japanese. Over six times as many Marines were evacuated due to disease and illness than were killed or wounded in action. Poor diet, little sleep, and the stress of combat conditions only made it worse for them, but the Americans kept going, supporting and encouraging each other, even bullying and cajoling when necessary. The spirit of teamwork and pride Carlson had worked so hard to foster in his men paid off in the jungles of Guadalcanal. A lesser force, not possessed of their determination and endurance, could not have stayed in the jungle so long or accomplished so much.

By November 25, the Japanese had been pushed back sufficiently for Carlson to begin the final part of his mission. It was time to conquer Mount Austen, the looming mountain abode of Pistol Pete. Removing the Japanese artillery from its elevated perch would make the Henderson Field perimeter that much more secure. Additionally, cutting the trail used to move supplies and troops for the Japanese would leave any enemy east of Henderson cut off, starving, and isolated. Already the Japanese troops seemed to be at the limit of their endurance. Patrols regularly found abandoned weapons and ammunition, things the normally disciplined Japanese soldiers would not discard casually. Soon Jacob Vouza’s scouts all had new rifles, courtesy of the Imperial Army.

Slowly the Raiders closed in on Pistol Pete, determined to find the elusive guns. On November 28, A and F Companies were advancing when they found a dug-in artillery emplacement stocked with 75mm shells—but no cannon. It was frustrating not to find their target, but at the same time Captain Schwerin was heartened—cannon could not be moved easily in this terrain. Pistol Pete had to be close. Meanwhile, Companies B and D searched for the trail. With dusk approaching, Lieutenant Oscar Peatross and his Raiders came out of the jungle onto a path. They followed it a short way up Mount Austen before darkness stopped them for the night. It was too dangerous to move in the dark; a close-range encounter with Japanese soldiers would be bloody and confusing. They could not be sure if it was the main supply route.

Finally, on November 30, a patrol winding its way down a slender ravine made an important discovery: a thin, barely noticeable length of wire, exactly the kind used to connect an artillery field telephone to its command element. Carefully, wary of enemy ambushes, the patrol followed the wire to the Lunga River. There, on the south bank, was a Japanese encampment devoid of enemy soldiers. Searching, the Marines found Pistol Pete sitting near a 37mm antitank gun. The overjoyed Raiders tore the gun apart, disassembling every part they could. At a nearby hill, they threw the components down into the thick jungle undergrowth, where the Japanese would have the devil’s own time finding them again. Pistol Pete was gone, its parts left to slowly rust away into the fetid soil.

“The Most Spectacular of Any of Our Engagements”

The same day, a short squad of six Raiders led by Corporal John Yancey made another discovery. A bivouacked Japanese company, 100 strong, sat on one of Mount Austen’s slopes, dozing with its guard down. Small arms leaned against trees in the middle of the campsite, and rain beat down heavily. Though badly outnumbered, Yancey was counting on the BARs and Thompsons his men carried to overcome the odds. With the advantage of surprise, the Marine squad ran right into the middle of the encampment and sprayed everyone with automatic fire. Unarmed, shocked, and with no chance to retrieve their weapons, those Japanese troops who did not fall where they lay tried to run uphill into the jungle or down into the nearby river.

The Raiders chased them and killed as many as they could. When the fight ended, the Marines could look out over the steaming barrels of their weapons and see the carnage they had wrought. Three-quarters of the enemy lay dead or dying where only moments before they had rested. Later, native scouts and a few Raiders moved among the Japanese, ramming their bayonets into any who yet drew breath. The bodies were dumped into a mass grave. Carlson was proud of the young corporal for showing such initiative, calling it “the most spectacular of any of our engagements.” For his actions, Yancey was later awarded a Navy Cross.

Peatross’ Patrol

Another sign the Japanese were weakening came on December 2. A patrol led by Lieutenant Peatross stumbled upon a small unit of enemy soldiers during a stout rainstorm. They had not bothered to post sentries around their perimeter, and all of them sat around an apparently sheltered fire they had built. Silently the Raiders moved in on their lulled quarry until they were a scant 50 yards away. Then, at the officer’s signal the entire patrol opened up with automatic weapons, unleashing a torrent of lead. Ten Japanese were felled within seconds.

Peatross moved among the bodies, searching for anything of intelligence value. The mere sight of them told him much. They were “emaciated beyond words, pale and sickly looking. Their uniforms were in rags, and although each had a rifle, not one had a full clip of ammunition..,” he later recalled. Between the generally poor state of Japanese logistics and the efforts of the Raiders to interdict their supplies and harass them, the Japanese around Mount Austen were reaching the end of their endurance.

One more piece of luck graced the Peatross patrol. Moving on from the battle site, they found a trail twisting through open fields and the slopes of Mount Austen toward the Mantanikau River. The path showed signs of frequent use. Peatross believed this was the main supply route they had been searching for. Though the Raiders were due to withdraw to the perimeter, Carlson requested permission to remain longer, in part to determine whether this trail was the supply route. Vandegrift allowed the Raiders to stay.

Six-Hours Uphill

Whatever Vandegrift allowed, Carlson had to sell the extra time in the jungle to his Marines, who expected to move back to Henderson Field. Many officers would have simply expected their troops to follow orders without question or complaint. Carlson had built his Raider battalion on the idea of shared hardship and camaraderie wherein even the lowest private knew the reason behind his orders. The grizzled Marine officer gathered his men and told them what he needed them to do.

There were six companies of Raiders present. Carlson said he was sending the three that had been in the jungle the longest to Henderson. These were C, D, and E Companies. He appointed Captain Washburn to lead them back. Since the Raiders were now located on the south side of the mountain, they would retrace their steps around it and back to the main American position. Carlson would lead Companies A, B, and F to Mount Austen, where a final mission had to be carried out.

One of the scout patrols had found an unoccupied Japanese defensive position on a ridge near the top of the mountain. Carlson hoped to get his Raiders there first and ambush the Japanese when they arrived. They would have to climb 1,500 feet up steep and difficult slopes and ridges, a task requiring all their strength and determination. After eliminating the enemy, this group would climb down the northern side of Mount Austen and proceed the two miles to Henderson Field.

The journey up the mountain on December 3 was a six-hour uphill slog through the jungle, struggling to ascend slopes slippery with wet leaves and vegetation. The almost daily rain added thick layers of mud. The sweating Marines were soon caked in grime as they hauled ammunition, supplies, and their own equipment doggedly upward. Carlson, apparently wanting to reach the summit quickly, allowed only one 20-minute rest during the march.

His sense of urgency paid off when they finally reached the empty position near the top. No sooner had the leading Raiders arrived to survey the opposite slope leading down toward Henderson than a group of Japanese troops was spotted coming up. Quickly the Raiders took cover and prepared to ambush their enemy, but the Japanese point man must have spotted something out of place. He signaled his comrades to take cover. For him it was too late; a burst of Raider fire cut him and two others down within seconds.

“I Made a Human Target of Myself But I Did the Job”

What followed was a classic example of Raider-Japanese jungle fighting. The Japanese formed a base of fire with machine guns that Carlson tried to outflank by sending a squad to each side. The Japanese responded with a flanking attack of their own, so Carlson replied by dispatching a platoon to each Japanese flank.

One of the flanking platoons was led by Lieutenant Jack Miller. He sent a native scout ahead as point with Pfc. Ray Bauml next in line and Miller himself third. The Marines moved single file through the thick foliage, a method often necessary to keep control of the group. The scout stopped and gestured that enemy troops were ahead. Miller stopped the platoon and issued his orders. He sent Bauml to one side of the trail with four Marines, while he took the rest to the opposite side. With Miller was his platoon sergeant, Victor Maghakian, nicknamed “Transport” due to his skill at obtaining vehicles, sometimes legitimately, sometimes not.

Bauml and the others pushed slowly forward in the dense vegetation, unable to see the enemy or even each other. The corporal heard some branches moving and made ready to shoot. It was a moment of tension, broken when Lieutenant Miller emerged and asked if Bauml had spotted anything yet. Since neither had, Miller began to move away. He had only gone a few steps when a burst of automatic fire shattered the quiet, tearing into the young officer. Bullets plunged into his chest, arms, and throat and shattered his jaw. He fell into the tall grass as Bauml lunged for cover behind some trees, firing as he ran. Enemy fire chased him, but the trees were thick enough to stop the bullets. Miller’s runner ran off to find a corpsman.

A short firefight erupted, and the Japanese were killed with two bursts by a BAR man who spotted them. Maghakian rushed through enemy fire to pull another wounded Marine out of harm’s way. He had no idea his lieutenant had also been hit. When the engagement ended, someone told him Miller had been hit as well. Maghakian and Miller were close, their relationship more of a friendship than a strict command affiliation. The platoon sergeant rushed to his fallen officer and found him being tended by a corpsman, who had given Miller morphine. Looking at Maghakian, Miller muttered his nickname, “Transport,” but could say no more. Nearby, a Raider found the weapon used to fell the platoon leader, a captured American Thompson.

It was more than Maghakian could bear. Wanting vengeance, the Marine began a war of his own. A nearby enemy machine-gun nest was firing on the Raiders, and somewhere a sniper was concealed in the trees. Maghakian told two Raiders to cover him as he moved down a ravine toward the machine gun. Armed with a grenade, the sergeant knew he would be exposing himself to the sniper but thought it was the only way to get him to give away his position. He ran down the ravine, zigzagging as the sniper tried to kill him. A bullet found Maghakian’s wrist, but the Marine silenced the machine gun. The sniper did indeed expose his location and was dead from American fire in a moment.

Maghakian later wrote, “I made a human target of myself but I did the job…. I did not care as long as I revenged [sic] Jack.” The corpsman tried to get Maghakian to evacuate to the rear, but the tough sergeant refused to leave until later when he had lost too much blood to continue.

The battle continued as Carlson brought the rest of the Raiders forward. Twenty-five Japanese died in one slight draw alone. Bodies lay scattered around, and Peatross had the job of checking them for intelligence. As he did so, one Japanese soldier sprang up and aimed his rifle. Carlson was nearby and instinctively shouted, “Shoot the bastard!” Peatross needed no encouragement, however. He raised his shotgun and blasted the enemy soldier at point-blank range. Private Ashley Fisher was wounded by a grenade tossed by a Japanese soldier playing dead. That soldier was also quickly shot down.

“Ahoy Raider!”

By the next morning, Miller was still hanging on and even joked about wanting a beer when they got to Henderson Field. When a fellow officer promised to find him a bottle, Miller said he wanted a case. Still, he and the other wounded needed care, and Carlson decided to move to Henderson Field right away. The enemy on Mount Austen had been defeated, and now it was time to go back. There was a trail leading back to the perimeter some two miles away; the Raiders could cover the distance in a few hours. They set out with B Company leading the way.

After moving some 500 yards, the trail straightened, and the Raiders worried about an ambush. Corporal Albert Hermiston led his fire team cautiously forward, checking for lurking enemy soldiers. Something was waiting for them. Just as Hermiston motioned for those behind to get down, a blast of machine-gun fire killed him and one other Marine. Another fire team moved to flank the enemy. One Marine, Pfc. Cyrill Matelski, saw an American helmet poking through the foliage. He gave the recognition signal, “Ahoy Raider!” and was promptly shot in the head. A Japanese soldier had used the helmet as a trick.

A third fire team was able to knock out the machine gun but was quickly outflanked itself by a Japanese riposte. Carlson ordered another flanking move, and this was successful in pushing the enemy back. There was one more casualty of the fight, however. While the wounded waited for the battle to end, Miller died. Carlson held a brief ceremony, and the young officer was buried alongside the trail to await retrieval by graves registration troops. Miller would receive a posthumous Navy Cross for his actions against the Japanese on December 3.

The End of Carlson’s Long Patrol

The rest of the journey to Henderson proved uneventful. When the Raiders ran into the Marine sentries at the perimeter, they looked like scarecrows. While they moved with pride, they were unshaven, emaciated, and covered with sores and all the minor injuries the jungle can inflict. Carlson cautioned his Raiders not to take any food or candy from anyone. He knew their stomachs could not take it. They did take new canteens as the Marines in the perimeter cheered them. Rumors had circulated claiming the Raiders had all died.

Carlson had achieved all his objectives for the long patrol and done great damage to the Japanese on Guadalcanal. He felt vindication for his training methods and the steadfast courage of his Raiders. The press seized upon the daring patrol and praised Carlson and the Raiders in newspapers across the country. It was the high point of Carlson’s career, and his battalion was awarded a unit citation by General Vandegrift.

Unfortunately, the Raider concept Carlson had pioneered soon became a casualty of war itself. The battalion was made part of the new 1st Marine Raider Regiment with a new commander, Lt. Col. Alan Shapley, who promptly instituted his own, more conventional way of running the unit. Carlson was made the regimental executive officer. By the summer of 1943, he was rotated home, ostensibly for medical treatment. He had ruffled too many feathers in the Marine high command with his unorthodox ways. By early 1944, the Raider Regiment itself was disbanded and reformed as a conventional regiment.

Still, the Raider concept eventually made headway in the Marine Corps. The fire team idea took hold, and both Marine and U.S. Army units use them in the rifle squad today. The discussions and critiques Carlson held with his Raiders after a mission or training event survive today as the AAR (After Action Review), used by military units to determine what went right or wrong and to suggest improvements.

Modern Marine special forces elements consider themselves descendants of Carlson’s unit, although the Marine Corps does not officially call them Raiders. Nevertheless, the men who called themselves Raiders earned their place in history.

How can I find out if my dad, William Junior Hazelton Jr. was in Carlson’s Raiders?

What’s not mentioned is that Carlson left behind 9 men on Makin who were later captured and executed. He also tried surrendering to a Japanese garrison that had been wiped out.

We’ve published at least a couple of stories on Carlson’s Makin Raid that might interest you. Here are links to them:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-makin-raid-what-really-happened-to-the-marines/

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/raid-on-makin/

Thanks. I found the links in my own after I posted that comment.