As the early days of the American Civil War were unfolding and the destiny of the republic was being contested on the battlefield, President Abraham Lincoln was engaged in a no less perilous type of battle. For Lincoln, the maintenance of Union loyalty within the border states of Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri and Delaware was of critical importance to the ultimate preservation of the nation.

“I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky,” he observed in the early days of the Civil War.

A difficult task, to be sure, and the Western Department’s commander sure didn’t make it easy for him.

As you’ll read inside “Lincoln vs. Frémont,” Lawrence Weber’s feature article in the Early Summer edition of the Civil War Quarterly, the Major General nicknamed “The Pathfinder” had his own plans for part of the nation’s contested regions.

A “Hasty Emancipation”

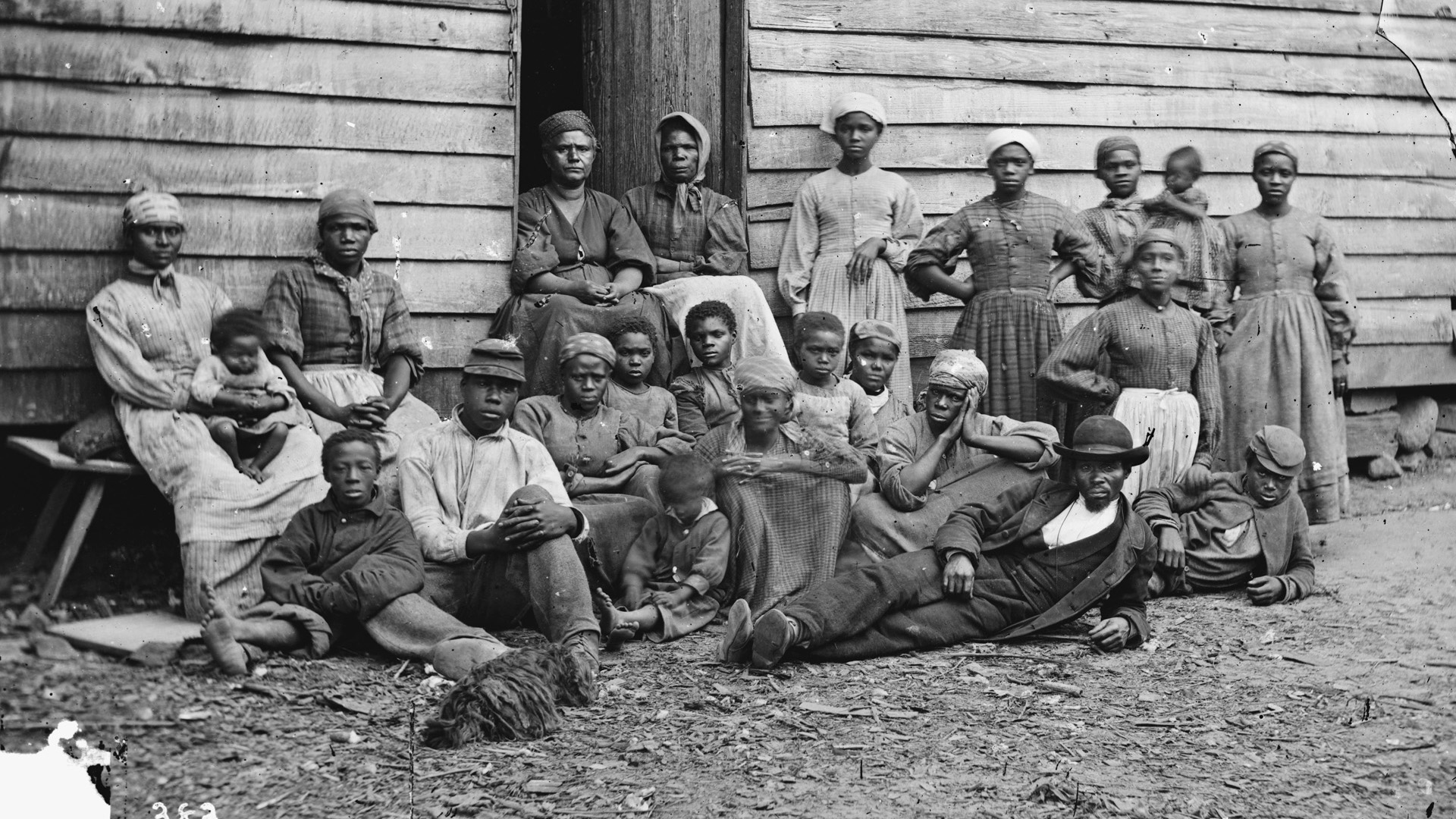

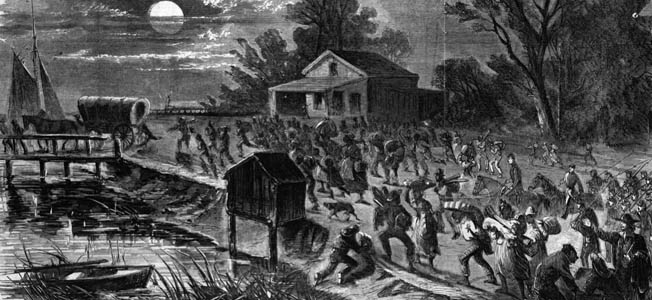

In less than three weeks after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, citing concerns for the public safety in Missouri, Frémont declared martial law in the state “in order to suppress disorders, to maintain as far as now practicable the public peace, and to give security and protection to the persons and property of loyal citizens.” That was all well and good, but what he said next threatened the entire course of the war. “The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken an active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use,” Fremont declared, “and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.”

Frémont’s de facto emancipation proclamation sent a shockwave through the Union. If the initial military failures at Fort Sumter, Bull Run, and Wilson’s Creek were not enough to pull the states of Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky away from the Union, targeting the institution of slavery within those states might effectively do the trick.

So what was the public’s reaction to Frémont’s radical declaration? What was President Lincoln’s? You can read all about it inside our current issue.

Of course, this is only one of many in-depth stories you’ll find in the Early Summer edition. Other features include:

“Brawl at Brawner’s Farm“

With Union and Confederate forces massing around a key railroad junction of Manassas, Stonewall Jackson’s II Corps confronted Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s Iron Brigade at the tiny hamlet of Groveton; it was a prelude of what was to come.

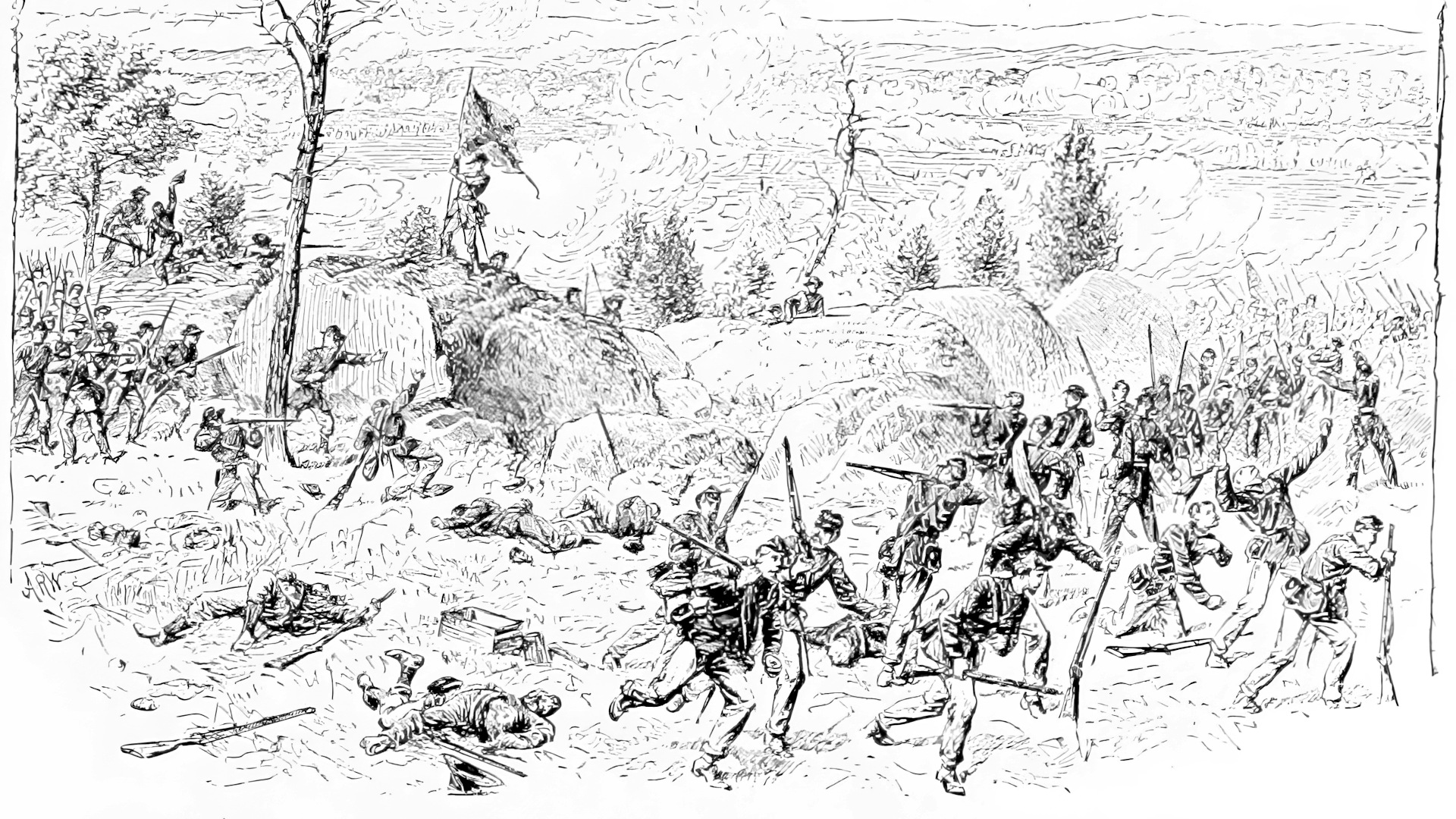

“4th U.S. Regulars at Gettysburg”

The proud Regulars in Company H, 4th U.S. Infantry, made a gallant stand in the blood-soaked wheatfield on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

“The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862”

Outraged by corrupt Indian agents and slow-arriving subsidies, Sioux warriors in Minnesota went on a bloody rampage in the summer of 1862, spreading panic throughout the North already at war.

“Invasion at Sabine Pass”

A clutch of Confederate Irishmen faced thousands of Federals in the battle for Texas.

What do you think of Frémont’s proclamation? Did you find President Lincoln’s response surprising? Let us know what you think about this and other features in this Civil War Quarterly issue in our comments section.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments