By David Lippman

In her previous life, she had been the Hansa-line freighter Goldenfels. She was launched in 1937 and displaced 7,862 tons. With her single stack, she looked like many other freighters traveling the world’s sea lanes.

When the German Navy requisitioned her as Hilfskreuzer 16—Auxiliary Cruiser 16—the Hansa crew just had time to unload her last cargo before the Bremen dockworkers started to tear her insides apart. They had to increase her fuel capacity from 1,268 tons to 3,000, water tanks to 1,200, and coal bunkers for her condensers to 1,000.

Hilfskreuzer 16 also required space to hold 92 mines, sand ballast, prisoners, live chickens, refrigerators, crew quarters, a seaplane, artificial ventilation, four torpedo tubes, six 5.9-inch guns, pigpens, potatoes, cabbages, charts of every ocean in the world, radio transmitters, and toilet paper. The guns were secondhand, coming from the old battleship Schlesien complete with pre-World War I rangefinders.

The ship also required a variety of camouflage devices. The guns had to be hidden behind flaps that could drop at seconds notice. At the touch of a lever, heavy steel flaps would slide upward to reveal the 5.9-inch guns. The rangefinder was hidden inside a water tank above the wheelhouse. Collapsible ventilators, removable posts, telescoping funnels, and masts all helped the ship change its identity.

When the work was done, only one thing remained, and that was her name. On December 14, 1939, Kapitan zur See Bernhard Rogge provided that at the ship’s commissioning ceremony, naming her Atlantis. Under that title, Hilfskreuzer 16 would set out on the longest ocean voyage in history and become the most successful disguised merchant raider in the history of warfare.

Rogge Assembles His Crew

Rogge needed men who could withstand a variety of climates, long hours and days of boredom, months at sea, and provide unquestioning obedience. Fortunately he could veto the Navy’s choices. More fortunately for Rogge, the personnel desks sent him capable men. Kapitanleutnant Erich Kühn, the executive officer, was a regular Navy man with strong character and leadership style. Rogge had known Kühn since 1936. Oberleutnant Lorenz Kasch, the gunnery officer, was another career man. Radio officer Oberleutnant Adolf Wenzel and demolition officer Johann-Heinrich Fehler were less experienced but impressed Rogge with their military bearing.

But Rogge vetoed other officers, demanding men from other warships and commands. Korvettenkapitan Fritz Lorenzen came aboard as administrative officer, Dr. Wolfgang Collmann as weather officer. The latter was a family friend.

Other officers were called up from the merchant navy. Navigation officer Kapitanleutnant Paul Kamenz had commanded merchant ships. The other merchant officers given commissions held master pilot’s or first mate’s certificates. Doctors Georg Reil and Hans-Bernhard Sprung were assigned to provide quality medical care.

Finally, an adjutant. Rogge rejected the Navy’s choice, an art professor, in favor of Leutnant Ulrich Mohr, a cheery chemistry Ph.D. who spoke a number of languages and had traveled in America, China, and Japan.

The Atlantis: A Master of Disguises

Rogge was told to proceed to sea to attack unescorted British shipping, sailing Friday, March 13, 1940. To avoid bad luck, he gained permission to weigh anchor at 11:55 pm on Thursday the 12th.

Amid darkness and cold, Atlantis sailed for Süderpiep in the North Sea right on time. To preserve secrecy, a sailor was left behind to pick up the ship’s mail every day and store it in an unused back room. At Süderpiep, Atlantis sailors repainted their ship to resemble a Norwegian freighter, Knute Nelson, and held a last gunnery drill. To scare off snoopers, Atlantis flew a yellow quarantine flag, while Rogge awaited bad weather for his breakout.

On March 31, Rogge’s men turned Knute Nelson into the Soviet Navy fleet auxiliary Kim. Rogge inspected his ship from a launch. He returned to report that everything looked fine, but the Soviet flag was flying upside down. A crewman changed that, and Atlantis sailed off to war amid gathering drizzle and heavy seas escorted by two S-boats and the submarine U-37.

The warships steamed into the Denmark Strait, evading floating ice chunks, amid water temperatures of 27 degrees Fahrenheit and air temperatures of minus 20. U-37 finally reached her point of departure and signaled “Best of luck and a safe return” before heading back to the Reich.

Atlantis changed disguises once again. Mohr broke out Lloyd’s Register of International Shipping and studied profiles. He needed a ship of about 8,000 tons with a cruiser stern, built after 1927. He eliminated those with white waterlines—impossible to paint at sea—and those that regularly worked with the Royal Navy or operated in the area. Of all the world’s shipping, there were only 26 candidates. Five were American, and Mohr did not know American call signs. Greek ships had far too specific a paint scheme to replicate. Rogge eliminated British, French, Belgian, and Dutch ships, whose locations were well known to the British. That left eight ships of Japanese registry.

Mohr disguised Atlantis as the Kokusai Company’s Kasii Maru, a four-year-old, 8,408-ton passenger freighter. On April 27, Kühn sent his petty officers into action, and Atlantis sailors converted the raider’s disguise. The Germans slapped yellow paint on the masts, black paint on the gray hull, and a large white K on the red-and-black smokestack. To paint the waterline properly, Rogge stopped his ship, pumped fuel from one side to another, and exposed the hull down to the waterline. Sailors scrambled down ropes and scaffolds to repaint the exposed surfaces.

“Heave to or I Will Fire”

On April 30, Atlantis entered her patrol area on the Cape Town-Freetown shipping lane. On May 2, a lookout spotted a contact. Crewmen in kimonos, some pushing prams, wandered the deck trying to look Japanese. At the last minute the ship turned out to be an Ellerman liner, the City of Exeter, which mounted guns and carried more than 200 passengers. Rogge declared there would be no attack.

The crew was disappointed, but Rogge’s reasons were simple. Atlantis could not accommodate 200 women, children, and elderly prisoners. Keeping its Japanese disguise, Atlantis watched the 9,654-ton liner rumble past, expecting a courtesy flag dip. None came. The Germans thought the British were being snooty. In fact, they were suspicious of seeing a Japanese ship in the South Atlantic and reported that fact, giving a full description of the “Japanese ship.”

The next day at 2 pm, about 500 miles off Cape Frio in Portuguese West Africa, Atlantis’ coxswain spotted a thin smoke cloud. Rogge cranked up his engines and cut the range quickly. The ship was clearly British. At 2:55 pm, Rogge dropped his false walls and camouflage, hoisted the German battle ensign and signaled with flags, “Heave to or I will fire,” and “Do not use your radio.” The transformation took two seconds. The British kept sailing on, so Rogge opened fire to warn the ship. It answered, “I understand your signal.” It then blew off steam as if to stop, faked a stop, and took off to starboard at flank speed.

Rogge opened fire and smashed the ship’s stern. Then Atlantis radiomen heard the ship broadcasting “QQQ,” the signal for a ship being stopped by a raider. Atlantis began broadcasting gibberish on the same frequency. Rogge ordered Kasch to resume firing. Finally, the British ship stopped.

At 3:26, Mohr, Fehler, and 10 men in Kriegsmarine uniforms went over in boats to seize the 6,199-ton freighter Scientist, under Captain Windsor, one of three men left aboard. The rest had abandoned ship. Fehler set charges to sink Scientist, but the ship refused to go down. Rogge tried 150mm guns to no avail and finally sank Scientist with a torpedo.

Capturing the Tirranna

The next stop was the tip of Africa and the Cape of Good Hope. On Friday, May 10, 1940, at 8:30 pm, Atlantis began laying mines 30 miles from the visible Cape Agulhas light. Lookouts could see car headlights on a coastal road. On an exceptionally calm and flat sea, Fehler laid neat rows of 92 Type-C electric mines, finishing the task at 1:17 am on May 11. Then Atlantis steamed off to the Indian Ocean at 10 knots to avoid British minesweepers.

Rogge ordered Mohr to hit the books again and find a new disguise. Mohr recommended and Rogge approved the year-old Dutch two-master Abbekerk, 7,906 tons. On May 21, Rogge massed his crew. Despite a squall, they whipped up the scaffolding. Japanese bright colors gave way to the Dutch browns and olive drab of the “Abbekerk.”

On June 10, lookouts spotted mastheads off the starboard beam. Rogge accelerated to 17.5 knots and a converging course, guns manned. At 11:35 am, the range was down to 5,400 yards and Rogge ordered the camouflage dropped. The guns trained out, and signalmen hoisted the German battle flag and signaled the order “Heave to.” The target ignored the command, so Rogge ordered Kasch to open fire. The target kept running. The chase finally ended with the Norwegian motor ship Tirranna surrendering, the crew trapped on their ship by splintered lifeboats.

The boarding party found shattered decks covered with blood, five dead, and many injured. The two-year-old 7,230-ton fast merchant ship Tirranna was sailing from Melbourne to Mombasa under Captain Gundersen and British Admiralty orders.

Rogge decided to keep Tirranna as a prize ship, hoping to capture a tanker that could fuel its voyage home to the Reich and put Lieutenant Waldmann, 12 Germans, seven Norwegians, and eight lascars aboard as a prize crew. They were to sail to a rendezvous point and wait for Atlantis until August 31. If Atlantis did not show up by then, they were to sail to the closest port sympathetic to Germany.

The two ships sailed off, Tirranna south, Atlantis north, in loose zigzags, hunting for Britons until they learned Tirranna had been seized. With that, Rogge had his men repaint their ship as if it was sailing under British orders, in accordance with papers found on Tirranna. Atlantis now masqueraded as the Norwegian 7,229-ton motor ship Tarifa.

“What Can You Expect From a Window Cleaner”

Rogge sailed toward the Sunda Strait-Mauritius route, cruising back and forth along it with no luck until 6:43 am on July 11, when lookouts reported smoke ahead. At 7,500 yards, the vessel sailed across Atlantis’s bow. It had one funnel, dark hull, dirty brown upper works, no flag … but an aft gun platform. It was British. But Mund, Goldenfels’s old first officer, said the ship looked like a former Hansa line ship. Mohr boarded the 7,506-ton City of Baghdad, an Ellerman liner, formerly the Hansa liner Geierfels, a British World War I reparation gain. Captain Armstrong White had not had time to destroy his secret papers.

On July 13, at 9:43 am, smoke was seen to the misty gray portside, a ship abaft. Atlantis turned 20 degrees to starboard, slowed to seven knots, and forced the other ship to pass astern. When the range dropped to 5,400 yards, Rogge opened fire with his 150mm guns. Four straight salvos missed. Salvos five and six hit the target just below the bridge and just above the waterline. The enemy hoisted, “I am stopping.”

It was the British 7,769-ton liner Kemmendine sailing from Cape Town to Rangoon. As the two ships stopped, Rogge saw women and children and felt relieved that the gunfire was over, hoping he could take a prize. Suddenly a lookout shouted, “She’s opened fire!” and a 75mm shell whizzed from Kemmendine toward Atlantis.

Enraged at this duplicity, Rogge opened fire, setting Kemmendine ablaze. Kamenz yelled, “There’s only one man on the gun. Some bloody lunatic who doesn’t know what’s going on.”

To complete the fiasco, Kemmendine sent up blazing piles of smoke, refusing to sink. Kasch put two torpedoes into the liner, and it finally broke in half, sinking in a classic V. Fortunately, nobody was injured, but there were 147 prisoners to care for: 26 officers, 86 lascars, and 35 passengers, which included five women and two children, the families of British servicemen and Indian merchants.

After the POWs were squared away, the next order of business was a court of inquiry on why Kemmendine fired on Atlantis nine minutes after surrendering. The board included Kemmendine’s skipper, Captain R.R. Reid, and City of Baghdad’s captain, Armstrong White.

The court determined that when Kemmendine was hit a steam pipe ruptured, which drowned out all communications to the stern gun. The gunner was a peacetime London window cleaner who simply ran up to the gun and pulled the lanyard on his own initiative.

“What can you expect from a window cleaner,” Rogge said, shrugging, as he endorsed and logged the report, ending the matter.

Sinking the Talleyrand

The following day, Berlin ordered Rogge to break radio silence and report his activities. He did so on July 15, saying he had sunk 30,000 tons of enemy shipping and had provisions for 85 more days. The British picked up the message but did not get a good fix.

On July 29, Atlantis hooked up with Tirranna and Rogge transferred his POWs and 420 tons of fuel to the captured Norwegian ship. Both Tirranna and Atlantis continued needed refits on August 2. Everyone was taking a break when Tirranna’s lookout blew the warning siren—mastheads approaching out of a rain cloud 400 yards away. Atlantis had only one working engine. Atlantis sailors dropped tools, brushes, and buckets. Crewmen in small boats raced over to their home ships and accommodation ladders.

On the bridge, Rogge ordered Kasch to open fire before realizing Kasch was on Tirranna. Kasch’s leading petty officer opened fire and missed the target by 400 yards. Rogge bellowed at the petty officer, and the second shots were near-misses. The third and fourth shots hit the target, and it stopped.

The visitor turned out to be the 13-year-old, German-built, 6,732-ton liner Talleyrand, now a Norwegian freighter. Captain Mathias Foyn said that he had seen Tirranna’s silhouette near another ship and thought his identical sister Norwegian had stopped to assist another vessel with engine trouble. Talleyrand had sailed over to help and was sunk with scuttling charges. Rogge continued the refit and ordered Tirranna home to St. Nazaire in France.

“I Require Medical Care”

On August 11, Atlantis was on the move, heading east toward Colombo, Singapore, and the Sunda Strait. For two weeks, nothing. At 2:45 am on August 24, Atlantis was 200 miles north of Rodriguez Island when smoke was sighted. Rogge headed at 14 knots on a course abaft of the enemy ship and closed in.

At 5:30, the enemy’s black-banded red funnel was clearly in view, and Rogge ordered Kasch to launch a torpedo. It ran wild, and Rogge ordered gunfire. Three direct hits, a wall of flame, and the enemy crew immediately abandoned ship. The enemy turned out to be an ordinary merchant ship, the 1928-built, 4,744-ton King City. The battered ship rolled over and slid to the bottom, leaving patches of coal burning on the oil-covered water.

Rogge kept moving around the Indian Ocean, and on September 9 at 9:30 am a lookout spotted a yellow funnel 14 miles away. It was a British tanker, and Atlantis changed course to intercept, running up to 17 knots, approaching the enemy through a rain squall. When the rain ended half an hour later, Rogge was 8,500 yards away and the tanker’s gun was trained on Atlantis.

At 8:01 am, the Briton raised his red ensign and hauled it down, requesting Atlantis to identify herself. Atlantis hoisted her battle flag and flipped out her guns, opening fire. The shots missed. The British sent out a QQQ message. Two minutes later, Atlantis lost electric steering and got locked into a starboard turn. The Briton tried to wriggle away, but Rogge sent men to the after steering flat. In minutes, Atlantis was answering helm orders and charged after the Briton, finally scoring hits.

The British QQQ messages stopped, and it signaled by flag, “I require medical care.” Rogge ceased fire. The British radio seemed to start up again, and Atlantis hurled more shells into the British ship, setting it ablaze and silencing the radio.

Mohr headed over to find the British ship a mess. Hot fuel oil was leaking everywhere. Mohr brought back 37 survivors from the 9,557-ton Athelking. Her skipper, Captain A.E. Tomkins, had been killed and the ship was subsequently sunk.

SS Benarty Scuttled

At noon the next day, Atlantis spotted another ship off the port quarter, 18 miles away. The two ships sailed on slightly converging courses for half an hour until the target spotted Atlantis. Then it headed north. Rogge, to fool the target, headed south. The target saw that and returned to its original heading. When Atlantis tried a converging course, the target sailed off.

Rogge summoned Pilot Officer Bulla and told him to attack and destroy the enemy ship’s radio antenna, using his trailing hook to swoop down between the masts and yank it away. If that failed, he would shoot up the funnel to scare the lascar crewmen.

Bulla’s attack did not work. He landed his plane next to Atlantis, but Rogge left the floating plane there, racing through a rain squall at 17 knots to attack. Battle flags snapping, Kasch fired warning shots at 3,400 yards. The Briton ignored them. The next shots went directly over the bridge of the ship, which then stopped.

As Mohr and his boarding party sailed over, the ship transmitted, “QQQ SS Benarty bombed by plane from ship…” Kasch opened fire and blasted open the ship’s number three hatch cover abaft of the bridge, setting the cargo on fire.

Just as Mohr arrived, Benarty’s crew was abandoning ship. Mohr ordered the British back aboard to help put out the fires. Benarty was a 5,800-ton coal-burner sailing from Rangoon to Liverpool under Captain Watt. Three scuttling charges sent Benarty to the bottom.

The Durmitor: Another Prize for the Atlantis

Atlantis sailed south-southeast toward the Australian trade routes at nine knots. At 10:33 pm on September 19, the port bridge lookout spotted a thick cloud of smoke. At 12:08 am on September 20, Atlantis attacked the British steamer Commissaire Ramel. As Mohr got ready to go over, Commissaire Ramel’s radio operator began sending an RRR report. Then 56 German shells shredded Commissaire Ramel and set her ablaze. Bad news came later when it was reported that Tirranna had been sunk by a British submarine, HMS Tuna, while anchored off Cap Le Ferret on the French coast, waiting for an escort of German patrol craft.

On October 22, just before dawn, Rogge saw a ship flying a neutral Yugoslavian flag. He decided to check its cargo. If it carried contraband, he could capture it and use it as a prison ship.

The ship turned out to be the 5,623-ton tramp Durmitor with a crew of 37 and a cargo of 8,200 tons of salt. Rogge decided to claim Durmitor as a prize. Lieutenant Emil Dehnel and 12 Germans went aboard the ship and were ordered to sail to a rendezvous point 200 miles south of Christmas Island.

The next day, Atlantis and Durmitor hooked up, and Rogge explained to his officer prisoners that conditions on Durmitor were bad. But if they put up with it, Durmitor would take them to the safety of Italian East Africa. More than 300 prisoners transferred to Durmitor that day. With Dehnel in command, the vessel completed an arduous trek to safety in Italian Somaliland.

“You Are My Prisoners!”

Meanwhile, Atlantis stayed in Sunda Strait until November 1 and then sailed for the Bay of Bengal. On the night of November 8, she spotted an eastbound ship against the moon on the Colombo-Singapore route. The target identified itself as the Norwegian tanker Teddy from Oslo and asked Atlantis for its identity. Rogge flashed back as HMS Antenor, a British armed merchant cruiser that closely resembled Atlantis. Teddy stopped, and Mohr sailed over in his cutter, wearing a Royal Navy jacket. As he stepped onto the Teddy, Mohr ripped open his jacket, slapped on a German Navy officer’s cap, and said, “I am an officer of the German Navy! You are my prisoners!”

The 6,748-ton tanker was captured without firing a shot. Aboard were 10,000 tons of fuel oil and 500 tons of diesel fuel. Rogge took Teddy as a prize and sent it to “Point Mangrove.”

Late on November 10, the He-114 seaplane spotted another tanker, and Rogge moved to intercept that night. The tanker spotted Atlantis and got off a QQQ with its location. Rogge let the broadcast continue but once again posed as HMS Antenor, hoping to seize another tanker through deception.

Mohr and Kamenz went over with 10 sailors clutching MP-40 submachine guns concealed under a tarpaulin. The tanker’s crew manned the rail in British helmets.

Mohr clambered up the accommodation ladder, ripped off his Royal Navy jacket, charged a Norwegian sailor, grabbed his rifle, and yelled “Hands up!” That did it. The Norwegians surrendered. Mohr raced up to the bridge, where Captain Leif Christian Krogh yielded the 8,306-ton tanker Ole Jacob and its 11,000 barrels of high-octane aviation fuel.

Rogge put Kamenz and a prize crew aboard. He sent Ole Jacob to “Point Rattang” 300 miles south and sailed away, listening to British shore stations calling for Ole Jacob.

Rogge’s Jeweled Samurai Sword

On November 11, Atlantis held a memorial for Armistice Day. Later, 250 miles southwest of Achin Head, Atlantis spotted a thin smoke cloud against the blue sky—an enemy ship 18 miles away. Rogge raced in.

The two ships converged at 9:04 am. The Briton broadcast a QQQ report, and Atlantis fired 5.9-inch shells into its bridge and radio room, killing everyone there. Mohr and his boarding party found blasted bodies all over the bridge of the 7,528-ton Automedon. They also found 15 bags of secret mail, including British merchant decoding tables, fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and naval intelligence reports. Next to the shattered radio console Mohr found a bag marked “Highly Confidential … To Be Destroyed.” Inside was a report addressed to “C-in-C Far East … To Be Opened Personally.”

Back on Atlantis, Mohr and Rogge broke open the bags. Mohr easily translated British merchant ship codes, Admiralty instructions, sailing orders, and a real prize, the War Cabinet Planning Division’s latest appreciation of the British Empire’s strength in the Far East. He gaped at deployments of Royal Air Force units and naval strength in Malaya, along with vast notes on the Singapore fortifications.

Having bagged three ships in four days, running his total up to 13, Rogge decided to head south. Two days later, Atlantis hooked up with Teddy, and Rogge decided to sink the ship. Despite her valuable fuel, he had no way of locating other German ships that could benefit from it.

Atlantis met Ole Jacob on November 14. Rogge ordered this ship to Japan, knowing the oil-thirsty Japanese could use her cargo of aviation fuel as well as the top secret documents on British Far East defenses. After taking on most of Ole Jacob’s diesel fuel, Rogge unloaded his latest prisoners on her.

Ole Jacob reached Kobe, Japan, on December 6. The Japanese took the secret British documents and at first could not believe them. Then, on April 27, 1942, they presented Rogge with a jeweled samurai sword, making him one of three Germans—the other two being Hermann Göring and Erwin Rommel—to receive such an award from Japan.

Christmas on the Atlantis

Rogge decided to give his crew a break for Christmas, sailing south to the desolate Kerguelen Islands. The Germans had surveyed the islands as part of their late 1930s Antarctic surveys and determined it had fresh water and no human beings.

On the way down, Atlantis’s radiomen picked up a signal from their sister raider, Pinguin, to Berlin, reporting she was sending the captured tanker Storstadt back to the Reich with 400 prisoners and 10,000 tons of diesel fuel. Rogge fired off a quick request for a rendezvous and was given grid square “Tulip.”

That evening, Storstadt arrived to fuel Atlantis and take on her 124 prisoners as well as food and water. During the fueling, a signal came from Berlin. Rogge had been awarded the Knight’s Cross. The next day was one of celebration.

Then Atlantis sailed for the Kerguelens. All hands took a break to celebrate Christmas, complete with artificial trees, caroling, Rogge reading the nativity, 14 more Iron Crosses, and bags of presents for the crew. These consisted of socks, ties, and tobacco from Atlantis’s various prizes.

On January 10, 1941, Atlantis ended 26 days in Gazelle Bay and put to sea with tanks full of fresh water and engines reconditioned. Rogge picked the Norwegian 7,256-ton freighter Tamesis, just one year old, as a new disguise for his ship.

“Stop, Don’t Use Radio”

On January 23, Bulla’s plane spotted a new target 60 miles north. Atlantis steamed after it. At nightfall, Rogge set course to intercept and found nothing. At dawn, he shot off Bulla’s seaplane again. Ten minutes later, the Briton was located 25 miles to the north. Bulla, armed with 110-pound bombs and a grappling hook to rip out the ship’s radio antenna, swooped in. He ripped the aerial from its mountings, then dropped his bombs and scored two direct hits.

At noon Atlantis began hurling 61 shells and scored eight hits. Blazing, the 5,144-ton Mandasor stopped engines. Mohr and Fehler sailed over to take off her crew. Fehler’s scuttling charges went off, and Mandasor slid into the water bow first, leaving a patch of debris and floating tea on the surface.

Now Atlantis steamed in circles on the Persian Gulf’s tanker routes. At 6:11 pm on January 31, Matrose Willi Freiwald spotted the 5,154-ton Speybank. The Briton also spotted Atlantis and swung away. In three minutes, Rogge opened fire. Mohr and his team took Speybank as a prize.

On February 2, Atlantis lookouts spotted an enemy ship heading west at 16 knots. Atlantis struck a parallel course, and the enemy sent off a “suspicious ship” report with her name, the Blue Funnel liner Troilus, a sister to Automedon. Troilus’s Captain R.S. Braddon kept his lookouts sharp, and they reported Atlantis’s movements at the horizon’s edge. Braddon’s radio crew fired off reports. Studying the reports, Rogge decided not to attack, a very wise move as the British aircraft carrier Formidable and the cruiser Hawkins were racing to answer the call.

Instead, Atlantis headed south and spotted another tanker. Rogge worked up a heading that would bring Atlantis and the tanker together just after nightfall. Atlantis and other German ships operating in the Indian Ocean badly needed fuel.

Rogge’s officers suggested making up a big sign that would read “Stop, Don’t Use Radio” in English, and draping that over Atlantis’s side, fully lit by searchlights as the crew unveiled its guns. Kasch would fire a warning shot. The British would fear their volatile cargo might explode and would surrender. Rogge agreed to try it, and the action was successful. Mohr ran up a ladder to find 43 Chinese and nine Norwegians on the 7,031-ton tanker Ketty Brovig racing around in terror. With a prize crew aboard, Ketty Brovig steamed off after makeshift repairs.

Rogge fired off a message to Berlin reporting 111,000 tons captured or sunk to date. He also asked to send Speybank home and rendezvous with the raider Kormoran and the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, both operating in the Indian Ocean, so the other ships could refuel from Ketty Brovig. Berlin ordered Atlantis instead to meet the supply ship Tannenfels and the Italian submarine Perla at “Nelke.” Both were short on fuel after fleeing Italian Somaliland one step ahead of the advancing British Army. Then Atlantis could meet Kormoran and Scheer.

Commandeering the Dresden

On February 8, Atlantis hooked up with Speybank and Ketty Brovig. The 7,480-ton Tannenfels, a sister to Atlantis in peacetime, showed up on the 10th, three days late due to a navigational error. She brought Lieutnant Dehnel and his Durmitor prize crew back to Atlantis. Dehnel took over Ketty Brovig, Tannenfels took over 103 prisoners, and everyone passed around food, sextants, charts, water, signal gear, even lifeboats.

On February 12, Atlantis and its flotilla puffed southward into worsening weather. Rogge did not tell anyone they were about to rendezvous with a German battleship. At noon, a lookout spotted a ship heading straight for them across heavy gray seas. When the 13,660-ton Admiral Scheer under Captain Theodor Krancke steamed up, it was the largest gathering of German warships outside European waters in the entire war. Soon enough, the ships parted.

A few days later, after an aborted attempt to rendezvous with Scheer for a second time, Rogge sent Speybank home, and she reached Bordeaux on May 12. Berlin ordered Rogge to send Ketty Brovig to rendezvous with the German ship Coburg and act as support for the raider Pinguin operating off Antarctica. Ketty Brovig was soon detached to rendezvous with Coburg; however, both were sunk by Commonwealth cruisers.

Atlantis sailed on through muggy heat. In his cabin, Rogge noted that he had so far captured or sunk 16 enemy ships, captured 919 prisoners, and caused 33 deaths. Atlantis was disrupting British trade routes as planned.

In the Atlantic, Atlantis met with the supply ship Dresden, which was supposed to bring fresh food. She did not. An idiotic German naval attaché in Brazil had loaded the fresh food on another ship, which lacked a refrigerator. Rogge was enraged. He ordered Dresden to stand by in case he picked up some prisoners.

The Diverse Passengers of the Zam Zam

A few hours after midnight on April 17, Rogge spotted a blacked-out ship with four masts. Rogge recognized it as a British Union Castle liner. He followed the ship as it zigzagged erratically. After nine minutes of gunfire, the ship blew off steam, started spewing lifeboats full of women and children, and ran out its flag—the banner of the neutral kingdom of Egypt.

Once the British troopship Leicestershire, the 8,299-ton ship was now the Egyptian liner Zam Zam, and she was carrying a passenger list of 202 that reflected the craziness of war, including American missionary families, 24 American ambulance drivers for a Free French brigade in Libya, 100 clergymen of 20 different denominations, 76 women, five of whom were pregnant, and 35 babies. The haul included several elderly Britons, four Belgians, two Greeks, one Italian, one Norwegian, six North Carolina tobacco merchants headed for Rhodesia, Fortune magazine editor Charles J.V. Murphy, and Life magazine photographer David E. Scherman.

The German 5.9-inch shells caught the liner by surprise and the ambulance drivers hung-over. One shell maimed ambulance group leader Frank Vicovari and British chiropractor Dr. Robert Starling. Another splinter landed in the brain of tobaccoman “Uncle Ned” Laughinghouse. He later died on Atlantis.

On Atlantis’s bridge, Rogge realized he was sitting on a major diplomatic disaster, and there was a writer and photographer from the Luce empire to record this whole affair for the American press. Rogge summoned his officers and ordered the entire crew to be on their best behavior and to treat the civilians with maximum generosity and kindness. Already, Zam Zam’s passengers were asking, “When is tea time?” “Where is the baby food?” and “When will the bar be open?”

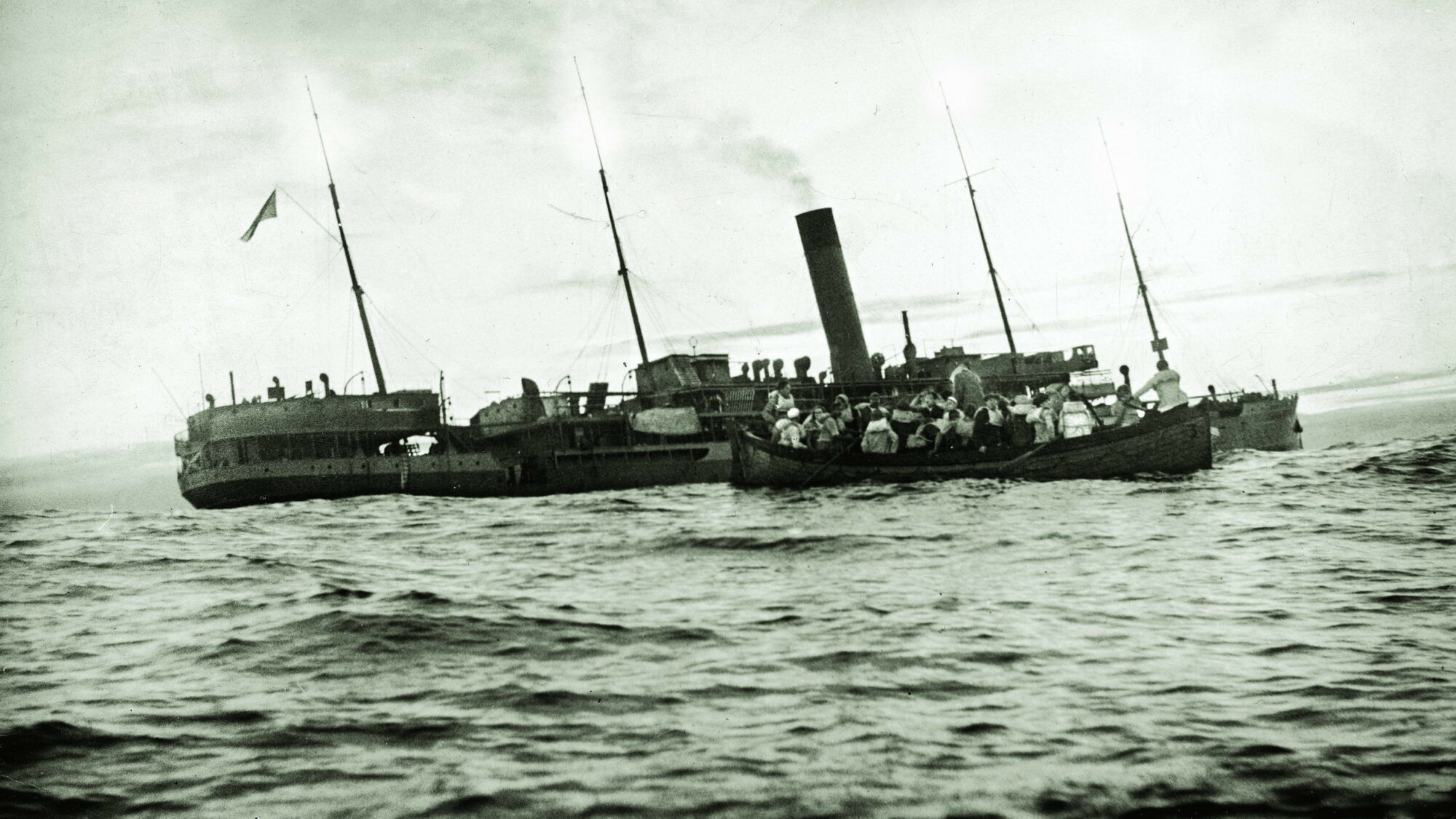

At 2 pm, Mohr was done, Zam Zam was ready for scuttling, and Mohr gave Scherman special permission to photograph the sinking, showing him where to stand.

The three charges on Zam Zam went off in quick succession, providing Scherman with dramatic images of the liner rolling over on her side. Then Rogge cranked up his engines and headed straight for Dresden. Zam Zam’s passengers complained about the sinking, and Rogge answered that Zam Zam had been sailing without lights on Admiralty orders and her $3 million worth of cargo was all for British troops fighting Germany from bases in Egypt.

The following morning Atlantis met up with Dresden and the 2,729-ton supply ship Alsterufer, which had a complete load of supplies for Atlantis, including three new Arado Ar-196A seaplanes and a load of personal mail for the crew.

The Zam Zam passengers went to Dresden. Atlantis then steamed back to war. For nine days, Dresden meandered the Atlantic with the passengers fighting tension and boredom. On April 26, the two German ships regrouped, and Rogge ordered Dresden to the nearest neutral port to release the captives. Atlantis kept the wounded Zam Zam passengers, including the American Vicovari.

Atlantis then plodded off with Alsterufer to meet the tanker Nordmark, while Dresden sailed for France. As Dresden sailed away, Scherman snapped a perfect bow-quarter, full-length shot of Atlantis.

On May 21, 1941, Dresden sailed into Saint-Jean-de-Luz in France, one day after the British Admiralty announced that Zam Zam was a month overdue and considered sunk. The Germans interrogated all aboard, held the Britons and Allied nationals, and freed the Americans, following direct orders from Hitler and Grand Admiral Erich Raeder not to enflame American public opinion. The Germans grabbed 1,000 frames of Scherman’s film to censor in Berlin, but he kept four rolls in a tube of toothpaste, another of shaving cream and two boxes of surgical gauze in a missionary doctor’s bag until they reached neutral Portugal.

From there, Murphy and Scherman flew to New York with their exclusive and their photograph of Atlantis, which the Royal Navy eagerly circulated to all of its commands.

A Record-Breacking 445 Days at Sea

Atlantis’s crew gave its ship yet another identity change. As Tamesis’s cover had been blown, Atlantis now became the four-year-old Dutch motor ship Brastagi. Just after midnight on May 14, Atlantis spotted a merchant ship on the Cape Town-Freetown route. Atlantis signaled the ship to stop, but it refused. Rogge swung a searchlight on the ship but it sailed right on. He opened fire with a warning shot, and the ship tried to escape. Further rounds hit home, and the ship began to sink. Mohr’s boarding party had no time to do anything but pull survivors out of the water. Within 30 minutes, the 25-year-old British steamship Rabaul, 5,618 tons, had gone down.

Atlantis had drifted along the Cape Town route for two days when Steuermannsmaat Rudolf de Graff spotted two ships on the horizon at 10 minutes past midnight on May 17, sailing on calm seas under a brilliant moon. Rogge sounded action stations. The British battleship HMS Nelson and the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle steamed by without incident.

On the 24th, Rogge launched his seaplane, and it found a British merchant ship. He steamed up to attack just after nightfall, and Atlantis’s first shot blasted open the radio room. The Briton tried to run, and Rogge hurled 10 more salvos, setting off massive explosions. The merchant headed right for Atlantis. Rogge ordered a torpedo attack. The torpedo malfunctioned and headed back to Atlantis. Kasch fired another one, which also did not work. The first torpedo swept past Atlantis’s bow. The second shot went wide. The third stopped the 4,530-ton SS Trafalgar. Mohr had time to rescue the crew before Trafalgar went down.

By now morale on Atlantis was sagging. Sixty percent of the crew were reservists with wives and families back home. By June 11, the ship had been at sea for 445 days, setting German and world records for consecutive days at sea.

Four Hits Out of a Hundred

On June 17, there was a break in the gloom when Bulla spotted the 4,762-ton British steamship Tottenham. Atlantis hurled a shell across her bow, but Tottenham sent out an RRR call and fired a shell back in defiance. Rogge opened fire and sank the Briton.

On June 22 Rogge spotted another ship and swooped in to attack right after dark. Only four of Rogge’s 100 rounds fired were hits. Rogge’s guns overheated and jammed. He was ready to give up the fight—and then the Briton surrendered. Mohr steamed over to grab the 21-year-old 5,372-ton motor vessel Balzac. Mohr brought back 47 of Balzac’s crew, and the ship sank.

On July 1, Atlantis met up with the raider Orion. Berlin signaled Atlantis, giving Rogge authority to stop in Dakar and to sail home. Heading home to Germany in mid-summer was dangerous. Instead, Atlantis would sail into the Pacific, continue to operate until mid-winter, and then head home for Germany under cover of cold and storms.

The crew accepted the order without complaint, which impressed Rogge. He made a note of that fact in his war log, calling their conduct “exemplary.” The raider headed east, and Rogge marked Atlantis’s 500th day at sea with a full-dress inspection. After that Atlantis swung around Australia and New Zealand.

On September 10, lookouts saw a poorly blacked-out ship popping out of a squall 700 miles north of Kermadec Island. The ship had a British silhouette, and Rogge raced after it. The Briton fired off a stream of QQQ radio messages, identifying it as the Norwegian 4,793-ton Silvaplana.

Rogge sent his latest prize to a rendezvous point 400 miles south of Tubusi Island. Hopefully, he could capture a tanker. He had no luck, so he sailed back to the meeting point. Meanwhile, Berlin informed him that the supply ship Munsterland was to cross paths with Atlantis. Rogge decided to meet Munsterland and then transfer stores to Silvaplana.

600th Day at Sea

On September 21, Rogge reached the rendezvous point to find another German raider, the Komet, under Rear Admiral Robert Eyssen, along with its Dutch prize, the Kota Nopan, lining up for fuel. Munsterland was late, delayed by a typhoon.

When Munsterland turned up, Eyssen demanded the bulk of the supplies. Rogge presented charts showing his men’s dietary requirements. Atlantis had not received a supply of fresh vegetables in 540 days. His men had only eaten a potato dish 16 times, and none for four months. Komet’s sailors had eaten potatoes three days ago.

Eyssen caved in but insisted that Komet get the bulk of Munsterland’s beer supply. Rogge transferred all but one of his 64 prisoners on Atlantis, the wounded American Vicovari, to Munsterland.

Then Rogge and Eyssen discussed their next moves. Rogge could not keep his men at sea much longer. He intended to operate in the Pacific until October 19, then sail into the South Atlantic. He planned a few more days of raiding there, and then home to Germany, arriving on December 20.

Atlantis then headed off still seeking enemy shipping. Nothing. Rogge proposed to stop off at an empty tropical island, give the men shore leave there, and use the seaplane for some air search. Mohr picked out an atoll named Vana Vana. On October 18, after a few days of rest, Atlantis hoisted anchor for the last time and headed for Cape Horn. Once past the South Shetland Islands, Rogge cranked Atlantis’s diesels to flank speed for the dash home. On Halloween, the crew marked its 600th day at sea.

“Enemy cruiser in sight!”

Now that Atlantis was headed home, it had excess fuel, and Berlin ordered the raider to act as a supply vessel for U-boats. Rogge also told Kuhn to do one more quick change—turn Atlantis into the Dutch motor ship Polyphemus.

Rogge was not happy to resupply U-boats on his way home. He believed such missions would only alert the British. He was right. The British knew that German U-boats were using that area as a rendezvous. A hunter group centered on the heavy cruisers HMS Dorsetshire and HMS Devonshire, which packed 8-inch guns, had been sent to the area.

On November 22, Atlantis lay waiting for U-126. Nobody noticed a speck in the sky. It was a British seaplane operating from Devonshire. The aircraft spotted Atlantis and reported her location to Devonshire’s Captain R.D. Oliver. The 9,750-ton cruiser moved to investigate.

Meanwhile, U-126 arrived and working parties connected fuel hoses and turned to. Whaleboats hauled supplies to the U-boat, while its skipper, Kapitanleutnant Ernst Bauer, and seven of his crewmen came aboard Atlantis for breakfast. Kielhorn asked permission to disassemble the Atlantis’s portside engine for repairs to a seized piston. Granted.

At 8:16 am, an Atlantis lookout shouted, “Enemy cruiser in sight! Enemy cruiser in sight!” Devonshire was bearing down from port. Atlantis’s crew severed and capped the fuel lines, and U-126 crash dived, leaving its commander aboard the raider.

“All Hands to the Lifeboats and Abandon Ship”

Rogge put Atlantis into a hard turn, intending to show Devonshire his stern and putting the U-boat between him and Devonshire. Rogge studied Devonshire’s three funnels through his binoculars. He knew the Briton could do 32 knots. Atlantis’s only chance was if U-126 could torpedo the Briton first. Rogge ordered all hands into life jackets and hoisted the Dutch flag, hoping to buy time.

Oliver hurled two 8-inch shells over Atlantis’s bow as a warning. Rogge got the message. He turned his ship broadside to the Briton and stopped engines. Using a captured British signal lamp, an Atlantis crewman signaled, “Polyphemus.” Rogge’s radiomen also tapped out a report, “RRR … SS Polyphemus … Unidentified ship has ordered me to stop.”

Oliver fired off a radio message to Freetown asking for the whereabouts of the real Polyphemus and kept his guns trained on Atlantis while zigzagging to avoid a torpedo attack. Meanwhile, in the aircraft the observer broke out his identity books, which included Scherman’s photograph of Atlantis, fresh from Life magazine. The plane reported to Oliver that the ship in the photo and the one in his binoculars had identical sterns, masts, and superstructure.

At 9:34, Freetown had an answer for Oliver: the ship under Devonshire’s guns was not Polyphemus. Her 8-inch shells blasted open the raider, starting fires, punching out the electricity and electrical steering. Rogge finally ordered: “All hands to the lifeboats and abandon ship.”

Buried under a smokescreen and fires, the crew calmly evacuated the ship. All were off by 9:43 am except Rogge, Mohr, Fehler and a demolition team, and Chief Petty Officer Wilhelm Pigors. Fehler and his men were planting demolition charges, while Mohr raced to his cabin through blazing wreckage to retrieve his camera. He saved it and returned to the boat deck as Fehler was climbing out. Fehler and his crew jumped into the water, leaving Mohr, Pigors, and Rogge aboard.

Rogge told Pigors to jump overboard and leave him alone. Pigors refused, saying that if Rogge went down with Atlantis so would he. That punched Rogge back to reality. As Mohr stepped over the rail, Rogge asked Pigors if everyone was off the ship. Pigors said that was the case. They leaped into the water. Amazingly, one man was left, Leading Seaman Heinz Muller, who had stayed at his radio until the ship was sinking beneath him.

At 9:36, Devonshire checked fire. At 10:02, Atlantis’s ammunition magazines exploded, and the ship heeled over. At 10:16, Atlantis’s bow rose out of the water and slid below the waves.

Surviving at Sea

Oliver, aware that a U-boat was present, declined to rescue the survivors. He turned around and headed northwest to recover his seaplane. He asked Freetown to send rescue ships, and two corvettes were immediately dispatched. The 350 shipwrecked Atlantis seamen—which included the only prisoner, the American Vicovari—floated or clung to wreckage.

With five rubber rafts, three steel cutters, two motor launches, and a lot of lashed-together debris, Atlantis’s crew had assembled a motley flotilla, with many wounded men. Only five were dead. Rogge and Bauer huddled to discuss what to do, and Bauer decided to tow the lifeboats to the nearest landfall. Unfortunately, one was Freetown, which meant POW status. Rogge chose a 12-day voyage to neutral Brazil, and Bauer reported this plan to Admiral Karl Dönitz, the boss of all U-boats.

The next day was hell. Eyes and lips began to swell and crack. Towlines broke and had to be repaired. At least they had gone 150 miles, which meant a five-day trip instead of a 12-day voyage. And the U-126 cook turned up trumps with two hot plates in creating hot meals for all. Berlin reacted, sending the 3,664-ton U-boat tender Python to meet U-126 and pick up the Atlantis survivors after 76 hours in the water.

102,000 Miles in 622 Days

Rogge puttered around the bridge, keeping an eye on the ship’s position and writing his after-action report. He closed it, “After successfully carrying out her mission and covering 102,000 miles in 622 days at sea, Atlantis was located and destroyed when on the point of returning home and while engaged on a supply operation which was not included in her operational orders…. Our bitterness at the loss of our ship has been intensified by the thought that we had to abandon her without a fight.”

Then Python was ordered away from Germany to refuel four U-boats. On November 30, Python met U-68 south of St. Helena. U-A turned up the next day. Atlantis crewmen, out of a job for once, stood around watching while Python and U-boat men hauled boxes or shifted torpedoes by crane. Then at 3:30 an Atlantis lookout spotted a three-funnel ship closing from 19 miles away. The U-boats executed crash dives.

Rogge was keenly aware of the situation. The attacking British cruiser, HMS Dorsetshire under Captain A.W.S. Agar, was Devonshire’s sister. Dorsetshire had already sunk Atlantis’s sister raider, Pinguin.

Dorsetshire signaled Python to identify herself, and Python’s captain ignored the request. U-A set up a firing solution and launched five torpedoes, but the range was too great. Dorsetshire closed to 11 miles and then hurled a warning salvo at Python. The German captain ordered his ship abandoned and scuttled.

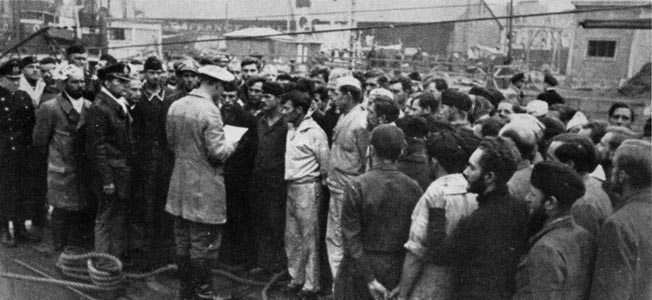

Dorsetshire held fire while the Python was abandoned. At 6:05, a scuttling charge went off and the former liner listed to port, rolling over for good at 6:21 pm. With the aid of several U-boats and Italian submarines, the survivors were eventually picked up. In late December, they arrived at St. Nazaire. Rogge himself came ashore on Christmas Day and assembled his crew on December 29 in a local cathedral. There he held muster and passed out the mountain of mail due to the men before giving them two days of liberty.

Rogge had his men muster at the train station on New Year’s Eve in new dress blues to take a special train to Berlin. There they received their actual decorations from Grand Admiral Erich Raeder himself, including a Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves for Rogge. All hands got a special Auxiliary Cruiser War Badge, but Rogge’s was 90 percent silver, holding 15 small diamonds in its swastika.

145,697 Tons of Shipping Eliminated

Rogge’s work for Atlantis was not done yet. He had to write his official report on the cruise, which became a training manual for future German disguised merchant raiders. Rogge reported that he had sunk 16 enemy ships and captured six others, eliminating 145,697 tons of Allied shipping and war materials. Atlantis had been away from home for 655 consecutive days, a new German record. Rogge had circumnavigated the globe on a voyage of 110,000 miles and survived 1,000 miles in lifeboats and 5,000 more miles in submarines before returning home. It was a fantastic achievement.

On March 1, 1943, Rogge was promoted to rear admiral and given responsibility for the selection and training of officer candidates. In September 1944, he took a command that included the 1st Naval Battle Group in the Baltic, which consisted of the pocket battleships Lützow and Admiral Scheer and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. After the war, he was investigated as a possible war criminal and cleared. He went into civilian shipping work.

When the German Navy was reconstituted in 1957, Rogge was one of the first officers recalled to duty, serving as commander of Military District I, and then all North Atlantic Treaty Organization ground, sea, and air forces defending northern Germany. He retired in 1962. When Rogge died in 1982, he was one of the most successful naval captains in history, warmly regarded by his former crewmen and his former enemies.

Rogge wrote two books on his journey aboard Atlantis, one of which was made into a movie, that told his story in simple and unemotional language.

Truly a fantastic story of this surface raider. I first read an abridged version of the story of the adventures of the Atlantis in the Reader’s Digest of 1954. I also believe that a movie was made of the exploits of this shipIf so, I will certainly like to follow up on this version.

Cheers,

H.A.

What an amazing story. Roughly 24 months in the seas with various disguises, several ships sunk, and evading the implacable pursuit of the ubiquitous Royal Navy. A cat and mouse journey until her sad end in the vastness of the south Atlantic some 900 miles from Recife harbor at Brazilian bulge. Most of crewmen saved by their tenacity and heroism after so many successful escapes. Bernhard Rogge, a true master of naval strategy of all times.

I worked a few years with Frank Vicovari, at the New York office of Mobil Oil Engineering in the 1970’s. He told me stories of that time in his life, but I was too young to really appreciate all he went through…..Reading this account of this episode really hits home…..God Bless Frank Vicovari….

.

My aunt Jamie and uncle Fred Henderson were medical missionaries on board the Zam Zam.

My great uncle Jacob was recruited by the captain to work aboard the Kriegsmarine 16. My uncle was studying to be a priest and the girls from the Hitler Youth took over the monastery. My uncle was forced to go home and sent working paper for Ast Landshut. I’m not sure how he was recruited or what job he performed. He later died in France possibly by Free French Militia. I wish there was a way to find more information. German documents are difficult to get.