By Joseph M. Horodyski

On Sunday, September 3, 1939, the day that Great Britain and France formally declared war on Germany after the Nazis’ invasion of Poland, the German supply ship Altmark concluded her stay at the refinery center of Port Arthur, Texas, where she had taken on a full cargo of diesel oil, and returned to sea. Her officers and crew, unaware of secret orders placing her on military duty, assumed that her next destination was the Dutch city of Rotterdam, where she would call during her return to Germany.

Altmark was an 11,000-ton oiler with a length of 540 feet and a beam of 70 feet. She boasted four nine-cylinder diesel engines that could push her through the water at a top speed of 21 knots, and she had a cargo capacity of 14,000 tons. Altmark had been commissioned in Kiel in November 1938. In her brief time in service, she had participated in practice maneuvers off the Spanish coast along with the pocket battleship Graf Spee during the Spanish Civil War. Her captain, Heinrich Dau, was a devoted party member who had spent his life at sea in the merchant marine and exhibited a stiff, authoritative manner that made it difficult for his junior officers to feel at ease.

Dau assembled the crew upon receiving a wireless signal of the declaration of war, informing his 134 men that Altmark was now on active duty and would serve as a supply ship for the 12,000-ton Graf Spee. They would not be returning to Germany for at least four months. Unknown to most of the crew, some of her cargo space already had been stuffed with excess food, spare parts, and ammunition for just such an eventuality. Most of the crew stood by glumly, but the captain and First Officer Friedrich Paulsen did their best to whip the crew into a suitable state of patriotic fervor.

First Rendezvous With the Graf Spee

Dau’s first decision was to begin conducting emergency boat drills that had so far been neglected on the voyage, in the event they should run into an enemy combatant. He then instructed the crew to repaint Altmark’s standard black-and-white trim a light yellow, adding a new name, Sogne, and new port of origin, Oslo, in an attempt to pass herself off as a neutral merchant ship.

Later that same day, Altmark rendezvoused for the first time with Graf Spee in the mid-Atlantic, halfway between Dakar and Trinidad. Altmark’s crew crowded the rails and took dozens of photos of the impressive warship. Six-inch-diameter pipelines were strung between the two ships to begin topping off Graf Spee’s oil bunkers, and Dau went across to confer with Captain Hans Langsdorff. They agreed that Graf Spee would meet up again with Altmark at a prearranged location on the 25th. Langsdorff assigned two wireless operators to Altmark to assist in the decryption of messages. After a full day of steaming together, the two ships parted. On the 4th, they crossed the equator for the first time.

The German government in Berlin vainly hoped that with the fall of Poland the Allied powers would come to their senses and arrive at a negotiated accord, but this did not happen. As Graf Spee gracefully rode the swells near Altmark during their second rendezvous on September 25, a coded message from Berlin arrived ordering Graf Spee into action. On the 26th, the ships parted company again, Langsdorff indicating that he would take his ship as far as possible from Africa, where British naval forces were close at hand, and test the waters off South America instead. Four days later, on September 30, he encountered and sank his first victim, the British steamer Clement.

On October 5 and 7, Graf Spee sank the British vessel Newton Beech and the freighter Ashlea. Langsdorff ordered the British crewmen transferred to Graf Spee as prisoners. On October 10, Graf Spee surprised and captured the British freighter Huntsman, a large vessel carrying raw rubber, wool, jute, ore, tea, and leather. Langsdorff barely had sufficient accommodation on board his own ship for Huntsman’s 84-man crew. He therefore appointed a prize crew to take her in charge, and together the two ships steamed for Graf Spee’s next rendezvous with Altmark.

Carrying Prisoners From the Graf Spee

Two days later, on the 14th, the three ships met in the mid-Atlantic. Langsdorff informed Dau that he would have to house the prisoners on board Altmark. Dau protested, wondering if it had been necessary to take prisoners at all rather than leaving them to the mercy of the Atlantic and pointing out that the large number of British seamen would pose a grave risk to his own vessel. Langsdorff ordered that the British prisoners be well cared for. Dau returned dejectedly to his own ship to prepare accommodations for the POWs. Late in the afternoon, the prisoners were transferred in relays to Altmark, where they would be housed in the bottom two decks, above the keep, with no natural light, little ventilation, and a table and makeshift shower as their only luxuries. Of the 141 prisoners, 67 were natives of India.

The prisoners had not been aboard Altmark long before it became painfully obvious to them that this was no neutral ship about to take them to freedom. Huntsman Captain A.H. Brown became senior officer among the motley crew of captives. Dau let the prisoners make themselves comfortable, instructing Altmark’s carpenters to help construct rudimentary tables and chairs for them and even allowing the Hindus among the prisoners to prepare their own meals from Huntsman’s captured provisions. Intercepted radio transmissions on October 22 indicated that Graf Spee had sunk another freighter, Trevanion.

On October 28, Graf Spee showed up unannounced, and Dau was invited over for a conference with Langsdorff. Dau became angry when he was instructed to take aboard yet another group of prisoners—his ship was already overcrowded, he protested. Langsdorff informed him that he intended to take Graf Spee off on an extended tour of the Indian Ocean. Altmark, in effect, was on her own. Dau returned to his ship in a foul mood. Graf Spee departed the next day for parts unknown.

On November 19, Altmark picked up a news report from Capetown that the freighter Africa Shell had been sunk four days earlier by an unknown German raider off Madagascar. Dau felt an immense wave of relief; Graf Spee was no doubt doubling back to the southern Atlantic. Altmark continued steaming in a designated square until the next scheduled rendezvous date with the battleship fell due.

One week later, Graf Spee came into view and took up station beside Altmark as refueling hoses were passed across to the raider. Dau expected another load of prisoners to be transferred into his custody, but only one man, Captain Patrick Dove of Africa Shell, had been taken prisoner. Langsdorff, aware of the overcrowding on Altmark, had allowed the rest of the ship’s crew to shove off in a lifeboat and make their way to the African coast.

Langsdorff issued a list of 27 prisoners currently aboard Altmark to be transferred back to Graf Spee, a list composed chiefly of captains, first officers, engineers, wireless operators and seamen in need of medical attention. It was his intention to make one last sweep off of the South American coast and then return home to Germany. The transfer was effected on the 27th, and the next day Graf Spee departed on what would prove to be her final voyage.

300 British Prisoners on the Altmark

Everything was in short supply on board Altmark—especially cigarettes. The British prisoners soon set up a barter system with the German crew. Five cigarettes from the German supply fetched a brand-new shirt, and eight bought a new pair of shoes, of which the British sailors seemed to have an inexhaustible supply. Conditions eased somewhat, but when the prisoners were advised to set their watches back an hour, it became clear that rather than returning to Europe or a neutral part of the ocean where they might be released, Altmark was in fact carrying them farther west.

Altmark had been sailing in circles for the last two days, awaiting Langsdorff’s return. On December 6, the two ships met up once again. While Graf Spee refueled, 144 more British prisoners were transferred over to Altmark. By now, Dau was increasingly nervous. The 300 British prisoners now on board outnumbered his crew by more than two-to-one. Any attempt to take over and seize Altmark might well succeed. At 8 am on the morning of the 7th, he addressed the captives. He reminded them that they were prisoners of war. He would try to make their conditions as comfortable as possible, but their treatment would depend on their good behavior. An Altmark sailor who had become too friendly with the British was court-martialed and sentenced to 21 days’ confinement.

Shortly afterward, Graf Spee sped off; her scout plane had sighted another quarry over the horizon. With Graf Spee’s signal flags spelling out “Auf Wiedersehen,” she soon disappeared from view. Neither Langsdorff nor Dau knew that they would never see each other again.

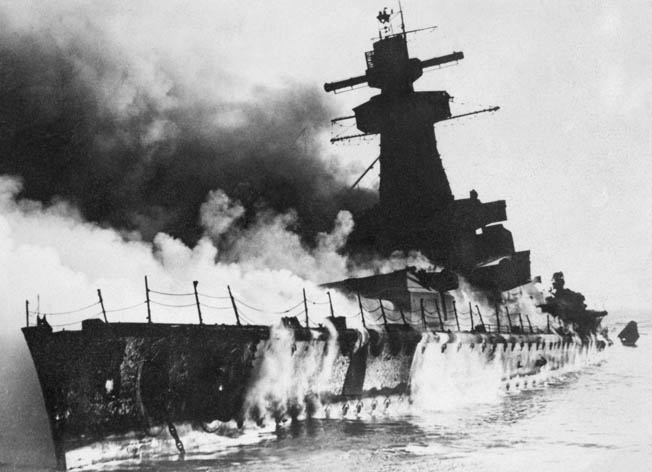

Langsdorff headed west to make one final sweep of the busy shipping lanes off South America before heading home in time for Christmas. But on the 13th, Graf Spee was sighted by a squadron of three British cruisers, and in a running battle lasting more than three hours, the German vessel was badly damaged and fled into the neutral Uruguayan port of Montevideo. The Uruguayan government ordered the ship to either leave within 72 hours or risk being interned for the duration of the war. Trapped in a harbor by superior British forces waiting for him outside, Langsdorff ordered Graf Spee scuttled to prevent her from falling into enemy hands. Then he shot himself.

The Search For the Altmark

Dau immediately altered course and attempted to sneak back to Germany. It would take daring, expert seamanship, nerve, and not a little luck. British naval forces, released from their hunt for the pocket battleship, were intent on preventing Altmark’s return to Germany. Over the wireless, Dau heard his ship’s description broadcast again and again: black hull, white deckhouses, yellow funnel. He set his crew to work changing Altmark’s appearance as much as possible, repainting the ship gray and adding wooden and canvas structures to alter the ship’s profile.

The British seamen did their best to get the word out to their comrades. Fifty prisoners at a time were allowed topside for an hour of fresh air and exercise whenever weather permitted. On one occasion a group of enterprising sailors prepared a note, giving the number of British sailors being held captive, the name of Altmark, and their current position as best as they could estimate it. They managed to slip the note into a discarded tin can and drop it overboard without being spotted. An alert lookout spotted the object floating in the ship’s wake and alerted the captain, who ordered Altmark stopped and the object retrieved. When he saw what it was, Dau became outraged. He ordered an investigation to determine who was responsible and threatened to have them shot. The German sailors made a half-hearted investigation. Frustrated, Dau ordered the number of British prisoners allowed topside to be cut in half.

Christmas Eve 1939 brought a little relaxation. Decorations were posted throughout the ship, and a special meal of roast mutton prepared for prisoners and German crew. In the spirit of the season, each prisoner was given a parcel containing half a bar of chocolate, three cigarettes, peppermint candy, soap, and toothbrushes (the last two were especially appreciated). Each German crew member was given a glass of beer, each British prisoner a cup of punch. Music and Christmas carols rang out far into the night.

But all was not well aboard Altmark. After thousands of miles of continuous sailing, her engines were in a sorry state. It was all her engineers could do to keep them running; spare parts were in short supply. There was some question as to whether they would hold out long enough to get them home. The British prisoners were allowed a bath only once a week, and the air below deck soon became fetid. In one compartment, 55 men were living, eating, and sleeping. Condensation caused it to be constantly wet. Second Officer Bob Goss of Ashlea requested a meeting with Dau and demanded the means to scrub down their compartments. Dau placed him solitary confinement for five days.

On January 28, Altmark recrossed the equator. Wary of an uprising, Dau permitted only three British sailors at a time to bring meals back to the rest of the men from the galley. German radio operators scanned the airwaves constantly for any sign that they had been spotted. In the next 10 days, Altmark’s lookouts reported other ships on at least six occasions, but due to the high seas, worsening weather, and foggy conditions in the North Atlantic, they escaped detection. On February 7, they passed close to Iceland, slipping successfully past the Faroe Islands. A small group of prisoners, who had been allowed on deck for a rare period of exercise, reported that the name Altmark had ominously reappeared on the bow. They must be getting close to German waters.

Stopped in Norwegian Waters

On February 13, Altmark suddenly came to rest. Rumors spread through the prisoners. Were they in Hamburg? Had they arrived in Germany? Dau came on the intercom system to address his crew; the British captives strained to hear. “Our voyage is nearly over,” he began. “We are now safely protected in neutral Norwegian waters. The Fatherland is so close that we can almost reach out and touch it. Two or three days at most, crossing the Skagerrak, and we shall be home to a hero’s welcome.”

At the Royal Navy’s base near Rosyth in the Firth of Forth, a group of British destroyers had just set out on an ice reconnaissance patrol off the Norwegian coast. Led by the cruiser Arethusa, the destroyers steamed out in line abreast: HMS Cossack, Sikh, Nubian, Ivanhoe, and Intrepid. The flotilla made for Norway on what was expected to be a routine patrol.

Altmark spent the morning of the 14th waiting for a coastal pilot to navigate her through the dangerous Norwegian waters, but none was forthcoming. After wasting the entire morning, Dau decided that they would have to make their own way. They got under way again, only to be intercepted by the Norwegian torpedo patrol boat Trygg. The Norwegian officer insisted on inspecting the ship. Dau led him up to Altmark’s bridge and showed him around, claiming that they were an unarmed tanker. The Norwegian seemed satisfied and issued a certificate that Altmark had been inspected and was free to continue. He told Dau that they might pick up a pilot at Alesund.

Upon arriving at Alesund, port officials again insisted on inspecting the ship. They refused to acknowledge Trygg’s letter and demanded to know if they were carrying prisoners or weapons. Dau protested his innocence, saying that they had already been searched once. By now the short Artic day was ending and darkness was approaching. The Norwegian official told Dau that Altmark would not be permitted to pass the vital fortress at Bergen in the dark.

The British prisoners began shouting, beating on the sides of the ship, banging utensils—anything to attract attention. Dau ordered his officers to put down the revolt using fire hoses; gunfire was to be avoided. Hoses were inserted in the hatch openings and cold water poured forth, drenching the prisoners and flooding the lavatory. The stench was overpowering. Filmy oil rose to the top of the three-inch-deep water. Electricity was cut off to that part of the ship, and the prisoners huddled together shivering in total darkness. Because of their behavior, Dau decreed that the prisoners would receive only bread and water the next day instead of regular rations.

“Permission or No Permission, I am Going on,”

By 6 pm, Altmark was again under way. “Permission or no permission, I am going on,” Dau insisted. The Norwegian pilots were told that they would be put ashore in the morning. Altmark passed Sogne Fjord, north of Bergen, soon after midnight. Dau estimated that they would be home within 24 hours, provided they could maintain full speed without further interruption. He then noticed with annoyance that Trygg was slowly trailing them. Soon a light began signaling them out of the darkness. It was the Norwegian destroyer Garm, whose captain demanded to board Altmark. Dau protested that it was the third time he had been intercepted and forced to stop by the Norwegians, an act of aggression on the part of a neutral country.

The Norwegian captain insisted that no ship of any nationality would be allowed to pass the fortified area of Bergen without being searched. Dau refused, insisting that his ship had been searched twice already. He demanded that Garm transmit a formal complaint to the German embassy in Oslo. He was advised he would have to bring it over in person. Dau felt the noose tightening. After a brief consultation with his senior officers, some of whom felt he was walking into a trap, Dau decided that his only course of action was to go. He motored over to Garm in a launch.

Norwegian officials refused to accept Dau’s assurances regarding the status of Altmark. Dau insisted that he needed to pass into the Skagerrak during the hours of darkness to avoid running into British naval patrols. “Today, tomorrow, what difference does it make” was the reply. Dau began to suspect that the Norwegians, despite their proclamation of neutrality, were in the pay of the British. He returned to his ship, barely containing his temper. Soon after Dau’s departure, the Bergen district commander sent an urgent signal to the British embassy in Olso, which quickly alerted the Admiralty that Altmark was steaming two miles off the Norwegian coast. The First Lord himself set the hunt in motion. He ordered all available aircraft in the area to be on the lookout for the German supply ship.

By 8 am on the 16th, Altmark was just north of Stavanger. The Skagerrak was only 100 miles ahead. Dau, who had managed only two hours of fitful sleep during the night, decided to stop for the day and resume the voyage under cover of darkness. By dawn the next day they would be in Germany.

But Altmark’s time had run out. All the delays during the previous 24 hours had eaten up precious hours of darkness. At 12:55 pm, an RAF Hudson spotted Altmark making eight knots in the fjord below and dove down for a closer look. All aircraft were under strict orders not to attack for fear of injuring the British sailors onboard. The Hudson quickly radioed the sighting and began shadowing the German ship. Night at these latitudes was only four hours away.

At 2:45 pm, Altmark’s lookouts spotted three ships ahead: the cruiser Arethusa, followed by the destroyers Intrepid and Ivanhoe. Altmark ran up to half speed. A new Norwegian gunboat, Skarv, was also shadowing them. Dau radioed that the ships ahead were armed warships sailing in Norwegian territorial waters, and that it was the Norwegians’ duty to stop them. The Norwegians ignored the signal.

The Capture of the Altmark

By 3:15 the British had approached close enough that Intrepid began to swing out a motorboat for boarding and put a shot across Altmark’s bows, ordering her to stop. Intrepid’s captain attempted to interpose his ship between Altmark and the coast. Altmark was now passing the entrance to ice-choked Jossingfjord. Dau ordered Altmark to enter at full speed. The ice groaned and creaked as Altmark forced her way through the packed ice. The ship shuddered, then made it through into the open water of the fjord before coming to a full stop. There was nowhere left to go.

Where Altmark had ground to a halt the fjord was only 400 yards wide. Skarv followed in Altmark’s wake and came to a halt 300 yards behind. Off to one side lay another Norwegian gunboat, Kjell. Outside the fjord’s entrance lay the two British destroyers who had attempted to intercept Altmark, joined by Cossack, whose captain, Philip Vian, was eager to board the tanker. The fjord was narrow, and it greatly restricted ship movement. He decided to go in alone.

Disregarding orders from the Norwegian vessels to leave their territorial waters, Vian ordered Cossack to resume moving toward Altmark. At around 11 pm, Cossack came to a grinding halt alongside Altmark. Her railings had been removed to allow the boarding party unimpeded access to Altmark, whose crew was standing by. Dau ordered the prisoners kept below to prevent them from overrunning the ship. Altmark slowly began moving astern in an attempt to use her superior weight to push the British destroyer into the steep banks of the fjord.

Vian anticipated Dau’s plan. He ordered Cossack swung around to meet Altmark’s weight full on, countering the German’s ship action with his own, and preventing Cossack from being pushed onto the ice. The two ships crunched together briefly as they came into contact, then started to separate. At that moment a 24-man boarding party led by Lt. Cmdr. Bradwell Turner started to jump across to Altmark, but only a few made it before the distance grew too great. Vian brought the British destroyer alongside the German supply ship again. Shouting and fixing bayonets, the British sailors quickly joined their comrades already on Altmark, whose crewmen were desperately trying to launch a lifeboat in an attempt to escape. One opened fire on the boarding party with a rifle. They were answered with a hail of small-arms fire. Two stewards and a stoker were hit. The lifeboat crashed onto the ice below.

Outnumbered six-to-one, the British boarders used the butts of their rifles to deal with any Altmark crewmen who resisted. A group quickly made its way to Altmark’s bridge, where Dau tried to pass himself off as a Norwegian pilot but then admitted to being Altmark’s captain. On the opposite side of Altmark, German sailors were trying to lower another lifeboat to escape from the British. Four or five had already begun making their way down the lines into the lifeboat. A British sailor raised his rifle and put several shots through the bottom of the lifeboat. Water immediately began filling the bottom of the boat, putting an end to the latest escape attempt.

“Leave All Germans Behind! I Don’t Want Them!”

Turner demanded to know where the British prisoners were being held. Dau offered to lead the way himself. The Germans began acting nervously, asking if they were going to be taken off the ship. Turner became suspicious. He asked the German officers whether Altmark had been fitted with scuttling charges. The officers on the bridge refused to answer directly, saying that it was a matter for the captain to address.

After the British boarded Altmark, Cossack withdrew to a distance of about four ship’s lengths, ready to deal with any Norwegian gunboats that might try to interfere. They could hear the shots being fired and shouts in German and English coming from Altmark. Cossack’s radio officer picked up signals from the German ship to Berlin, saying that they were being boarded and murdered by British sailors. They asked that ships and aircraft be sent to their assistance. The ship was set to blow at midnight.

Vian ordered the rescue operation to be speeded up. He brought Cossack back alongside Altmark. At that moment a cry of “Man overboard!” rang out. Two British sailors immediately jumped into the freezing water, took hold of the man, and swam to safety. To their surprise, the man turned out to be a German sailor who had jumped overboard in a desperate bid to escape. He was already dead.

Turner and four or five British sailors, led by Dau, made their way down to one of the cargo hatches. The cover was opened and flung back. Turner called down into the blackness, “Any Englishmen down there?” Almost 300 voices responded at once, “Yes, we’re all English down here.” “Then come on up. The Navy’s here!” It was a moment no one, prisoners or rescuers, would ever forget.

One by one the prisoners began to make their way up a ladder. Dau meekly apologized as they began to gather on deck, but the freed men ignored him. One British prisoner walked over to where some Germans were being held at gunpoint and, fulfilling a promise he had made to himself, punched the first German he could. “What the bloody hell kept you?” some of the prisoners said.

Vian watched from Cossack’s bridge as the prisoners crossed to his ship in a steady stream. It was 15 minutes to midnight. Some of the British boarders began leading a group of German prisoners over to Cossack at gunpoint. “Leave them, you fool!” Vian called out. “Leave all Germans behind! I don’t want them!” The British sailors were happy to comply. The last of the boarding party rifled through Dau’s personal safe for confidential papers and helped themselves to a swastika-decorated paperweight and a few other choice items as souvenirs. Dau cursed them as thieves and criminals.

“DASHING RESCUE”

The last of the British captives had now left their prison ship. Some were already down in Cossack’s mess eating their first decent meal in weeks. Vian took one last look around from Cossack’s bridge. Altmark, only moments before alive with noise and activity, was now silent. Searchlights swept the length of the tanker one last time, then Vian ordered his ship to cast off. Cossack slowly moved out of Jossingfjord, carrying the liberated prisoners toward the open sea and their voyage home.

The London Times headline the next day rang out in bold letters: “DASHING RESCUE.” Newsreel cameras were dockside to record the prisoners’ homecoming. Winston Churchill made the most of the success, praising the Royal Navy for liberating the British seamen from their floating prison and gallantly rescuing a drowning German seaman (without reporting that he died moments later). For the British public, the Altmark affair was the one bright spot in a long winter of bad news, the final end to the saga of Graf Spee.

As it turned out, Altmark did not blow up after all. No scuttling charges had been set. Altmark was soon repaired and sailed under Dau’s command to Kiel harbor. Renamed Uckermark and given a new captain, she returned to sea. On November 30, 1942, she was in Yokohama harbor, Japan, alongside the German auxiliary cruiser Thor, which she was in the midst of resupplying, when she suddenly exploded and sank to the bottom of the harbor. Sabotage was suspected but never proved. Some 53 of her crew, the majority of them veterans of the Graf Spee cruise of 1939, were killed and an equal number wounded. Their former captain, Heinrich Dau, was not among them. In forced retirement, he remained in Germany and took his own life on the day that the Nazis surrendered in May 1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments