By Kelly Bell

It was already December 8, 1941, on Wake Island’s side of the international date line. The Americans on the tiny specks of land in the western Pacific Ocean roused themselves at 6 am. Fifty minutes later, the garrison’s U.S. Army Signal Corps team opened its daily communications with faraway Hickam Field at Pearl Harbor. At first the radiomen were befuddled by the Hawaiian transmission, which seemed to indicate that Japanese warplanes were attacking the base. Hearing the report, Wake’s commander, Marine Corps Major James Devereux, made further efforts to clarify the garbled message. He soon received a coded communication that Pearl Harbor was indeed under devastating assault from carrier-based Japanese aircraft.

Ordering the bugler to sound the call to arms, Devereux informed his assembling troops that it was no drill—America had gone to war. Within 45 minutes, the base’s defense positions were manned and prepped for combat. This did not interfere with the Marines’ daily salute to their country. At 8 am, the leathernecks stood at attention and saluted their nation’s flag as it was raised. The colors would fly nonstop throughout the coming siege.

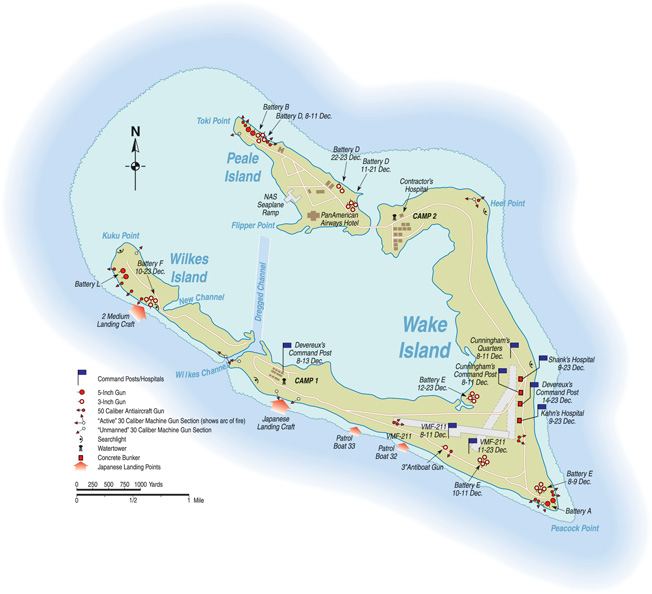

The Three Strategic Wake Islands

Wake Island is actually three islands, Wake, Wilkes, and Peale, surrounding a central lagoon and encircled by a coral reef. With no indigenous inhabitants except for stunted trees and a rare species of rat, the islands are barely 20 feet above sea level at their highest and cover a scant four square miles of land. Before now, Wake had not held any great significance. The United States had taken over the atoll in 1899 as a spoil of the Spanish-American War. Lying far off the main shipping lanes, it was mostly ignored for the next four decades, until the development of the airplane began to change Wake’s strategic status.

Centrally sited between two other American possessions, Guam and Midway islands, Wake made a convenient way station for the newly established Pan-American Airways, and the Philippine Clipper passenger flying boat regularly landed in the lagoon for refueling. After 1935, travelers could also check into the opulent Pan-Am Hotel on the island. Meanwhile, the American military began to develop Wake for its own aviation purposes.

As aerial technology advanced, it became evident that air power would be a major factor in any coming war. By early 1941 there was little doubt that America and Japan would soon be coming to blows, and the U.S. Navy sent a 1,100-man force of civilian contractors and workmen to Wake Island to commence construction of a military airfield and seaplane base. The laborers were still transforming the atoll into a military post when the garrison arrived in October 1941.

The 38-year-old Devereux commanded the 400 Marines who would become the resident occupying force. A veteran of combat in Nicaragua, China, and the Philippines, Devereux was competent and industrious. As soon as his men had unloaded and installed their artillery, machine guns, searchlights, small arms, and supporting units, he set them to assist the civilians in their labors. Working 12 hours a day, seven days a week, the leathernecks dug weapons pits, gun emplacements, air raid shelters, and sundry fortifications, camouflaging all of them. A direct Japanese invasion was not anticipated at Wake Island. Washington expected the Japanese to sit offshore in warships and attempt to neutralize the stronghold by naval shelling. Still, as a precaution, the ever-thorough Devereux constructed shore defenses in case of enemy landings. Under his ministrations, Wake became a fortress.

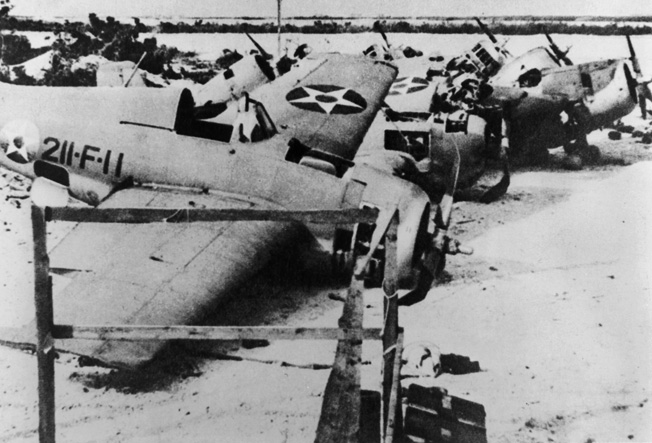

On November 28, Navy Commander Winfield Scott Cunningham flew to the island to assume overall command, and Devereux reverted to commander of all ground troops. While tensions grew, American-built B-17 Flying Fortresses in transit from California to the Philippines began landing on the brand-new runway to refuel. The presence of the bombers seemed to imply that the days of peace were running out. On December 4, 12 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise arrived to form Wake’s Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-211 commanded by Major Paul Putnam. Devereux had not had time to build fighter revetments, so the precious Wildcats could not be parked under cover. The Grummans would be conspicuous and vulnerable on the ground when the blow fell four days later.

On December 6, Devereux was so pleased with his men’s performance during combat drills that he gave them the rest of the weekend off to swim, lounge, read, fish, play football, write, and read letters just delivered by the Clipper. The next day, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and then turned their attentions on the previously sleepy enclave at Wake Island.

“So Close You Could See the Gunner’s Teeth”

At 11:58 am on December 8, 36 twin-engine Japanese bombers, having taken off from Roi-Namur, 700 miles to the south in the Marshall Islands, managed to catch the defenders by surprise by approaching through a rain squall. The bombers did extensive damage, igniting towering fuel-fed fires and strafing with impunity the startled anti-aircraft gunners who tried vainly to find the range. Seven of the island’s 12 vital Grumman fighters were destroyed and another was heavily damaged. Four Marine pilots—Lieutenants Frank Holden, Henry G. Webb, George Graves, and Robert Conderman—were killed on the ground while sprinting for their planes.

Japanese bombs pulverized warehouses containing spare parts, machinery, manuals, and tools, and they knocked out the island’s ground-to-air radio link. Twenty-three Americans were killed and another 11 wounded. Adding insult to injury, the Japanese pilots could be seen grinning widely and wiggling their wings in victory as they flew away. “The planes were so close you could see the gunners’ teeth,” recalled civilian contractor Benjamin F. Comstock, Jr.

Four of the Wildcats were spared because they had been absent on patrol at the time of the first attack. At 11 am on December 9, two of these planes, flown by 2nd Lieutenant David Kliewer and Technical Sergeant William J. Hamilton, were aloft when the second formation of enemy bombers approached. The two Americans immediately attacked the unescorted bombers, sending one down in flames, before having to break off their runs when their own anti-aircraft gunners opened fire.

Targeting the civilian bivouac and hospital, the Japanese bombers were savaged by flak. By the time they departed, six were trailing smoke. One exploded just offshore. Part of the Japanese 24th Air Flotilla, the returning pilots surprised their superiors with reports of the prickly reception they had received. Wake Island, it appeared, would be a harder nut to crack than so many other Allied outposts had proved to be during the waning days of 1941.

When the Japanese sent 26 bombers back to attack Wake on December 10, they were careful to approach from the east instead of the south, but the misdirection did them little good. The first wave carefully dropped its bombs on the coordinates of the anti-aircraft emplacements as reported by the previous day’s flight crews, but Devereux had anticipated this and moved the flak pits to different positions. The Japanese unloaded on dummy emplacements while American gunners opened fire from unexpected locations. The pilots were flying higher than on the previous day, at 18,000 feet, but the lofty altitude threw off the bombardiers’ aim and most of the bombs splashed harmlessly into the lagoon. One stray round crashed into a storage shed containing 125 tons of construction-grade TNT, setting off an explosion so powerful that it stripped the leaves off all the island’s trees. But only two Americans were killed and six others wounded. Again many of the bombers left trailing smoke, and Wildcat pilot Captain Henry Elrod shot down two enemy bombers.

The Plan to Take Wake Island

The next day, the American outpost of Guam fell to the Japanese, along with Makin, a British possession. As a Japanese invasion flotilla approached Wake Island, its tactical commander, Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka, was confident that his own landings, scheduled for December 11, would have an easy time of it. The Japanese fleet consisted of the state-of-the-art light cruiser Yubari, two older cruisers, six destroyers, two destroyer transports, two transports, and two submarines. At 3 am on December 11, the task force came in sight of its objective, and the warships commenced assuming their pre-landing bombardment positions. The plan called for the shelling to cover 300 naval infantry troops as they landed on Wake Island while another 150 came ashore on Wilkes. After these troops established themselves, they were to be reinforced by sailors from the destroyers.

The Japanese strategy quickly came unglued. American lookouts immediately noticed the convoy and woke Devereux. His first action was to telephone his shore batteries and order them to hold fire until he ordered them to shoot. By 5 am it was light enough to see through field glasses that the cruisers’ rifles outranged his own 5-inch shore batteries, and he would have to lull the Japanese into coming within range of his guns. Considering the bomber crews’ overly optimistic reports, this was not difficult. Devereux was careful to instruct Putnam to not take off with his four Wildcats until after the beach artillery opened fire. The attackers would be totally surprised by their blistering reception.

The Land-Sea Artillery Duel

Kajioka’s ships opened fire at 5:30, strangely concentrating on the beach and civilian contractors’ camp, doing little damage to the defenses. Followed by the rest of the warships, Yubari was steaming parallel to Wake’s southern shore. The shelling ignited diesel oil tanks, producing billowing clouds of thick black smoke that obscured the shipboard gunners’ aim, making the barrage even more ineffectual. After their first run Yubari and two of the destroyer transports reversed direction, turning inshore in the process. At this point the other two cruisers, three destroyers, and two transports took up positions off Wilkes’s western shore.

At the end of her second bombardment run, Yubari again reversed direction by turning inshore, bringing her within 4,500 yards of Marine Battery A on Peacock Point. At 6:10 am, Devereux gave artillery 1st Lieutenant Clarence A. Barninger permission to fire. The first rounds were off, passing harmlessly over the cruiser, which instantly turned away and began evasive action, but it would take her a few minutes to get out of range. She made it to 5,700 yards before two of Barninger’s 5-inchers crashed through her starboard side, exploding in the boiler room and machinery spaces.

Yubari shook violently and began issuing black smoke and clouds of steam, scalding many of her crewmen. Her skipper kept her on course away from the beach, but at 7,000 yards two more rounds punched through her hull just behind where the first ones had struck. One of the destroyers tried to hide the cruiser by laying a smoke screen, but was herself hit and forced to withdraw with a destroyed forecastle. Slowed by extensive damage, Yubari tried to pull out of range, but a final round from Battery A pulverized her forward turret. The defenders were just getting started.

Although the previous night’s dynamite blast had damaged the rangefinder of Battery L on Kuku Point, Marine 2nd Lieutenant John A. McAlister and his gun crew were determined to make a showing in the unfolding battle. When they received clearance to open fire, the destroyer Hayate was sitting complacently broadside just 4,500 yards offshore. Estimating the range, McAlister began firing. Two shells from his third volley hit the target squarely amidships, setting off a massive internal explosion that broke the destroyer in two. Both halves of Hayate sank like ax heads, taking the entire crew with them.

Meanwhile, on Toki Point, Battery B, commanded by 1st Lieutenant Woodrow M. Kessler, gamely engaged three destroyers at 10,000 yards. The Japanese soon realized what a dogfight they were actually in, and when one of Kessler’s rounds set the leading destroyer afire at 7 am, Kajioka prudently if ruefully ordered a withdrawal. The order came too late for some of his command, since part of the contingent of landing barges had already started for the beaches. While trying to reverse course in the heavy swell, several of the landing craft capsized, drowning the heavily laden men aboard.

Flight of the Wildcats

At this point, the four Wildcats attacked the enemy flotilla. Thinking it unnecessary, the Japanese had not brought along a carrier and hence had no air cover. The warplanes assaulted their targets with total abandon. Plunging through clouds of flak, they machine-gunned and dive-bombed the ships repeatedly, hitting both of the older cruisers, a destroyer, a destroyer transport and a transport. At 7:30, Elrod dropped two 100-pound bombs directly onto the destroyer Kisaragi’s rack of depth charges, setting off an explosion so powerful it virtually disintegrated the ship and killed every man on board.

When Kajioka radioed news of his setback, 30 Japanese bombers took off from Roi-Namur, arriving at 10 am. Two of the four Wildcats had been so seriously damaged in the strafing attacks they were no longer airworthy, but Lieutenants Davidson and Kinney jumped into the remaining two fighters and ripped into the approaching bombers, downing two and setting a third on fire. Flak knocked down another and sent one away trailing smoke. The bombs dropped in this raid did little damage, not even wounding any Americans. In fact, the day’s losses on Wake amounted to just four Marines injured and none killed. Japanese losses on December 11 were approximately 700 killed, an undetermined number wounded, two destroyers sunk, the brand-new Yubari crippled, and six other vessels damaged. The attack by the bomber formation had resulted in nothing more than its own decimation. Kajioka, meanwhile, was summoned to an interview with his immediate superior, a livid Vice Admiral Nariyoshi Inouye.

Elsewhere throughout the Pacific Basin, Japanese forces were enjoying an unbroken string of resounding victories that would continue for the next several months. Only Wake was presenting any difficulties. Considering the traditional Japanese emphasis on avoiding loss of face, Inouye was frantic to hastily neutralize this troublesome outpost. He informed Kajioka that the invasion fleet would be significantly reinforced, and aircraft carriers included. Wake would be taken, Inouye bellowed, at all costs.

Back on Wake Island, the American defenders erupted in disbelieving joy at the enemy repulse, spraying each other with water and warm beer. Cunningham compared the celebration to a fraternity picnic, noting that “war whoops of joy split the air.” Devereux’s radio operator turned to the nervy commander: “It’s been quite a day, Major, hasn’t it?” he said.

Following the repulse of the initial Japanese invasion attempt, there was a hiatus in the action. The 24th Air Flotilla launched a few desultory air raids but did not measurably interrupt the Americans’ work on their fortifications, which included bulldozing revetments for the Combat Air Patrol. Cunningham’s men feverishly worked on repairing VMF-211’s damaged Wildcats, getting two airworthy and constructing a third from cannibalized parts. These craft quickly proved their worth as their pilots shot down a long-range flying boat on December 12. That same evening, Kliewer used his 100-pound general purpose bombs to sink a submarine 25 miles southeast of Wake. The submarine had apparently been providing radio direction finding for approaching bombers. The next day Japanese bombers failed to appear.

Abortive Rescue of Wake’s Defenders

When word reached Hawaii of the unfolding situation on Wake, the Pacific Fleet’s commander, Admiral Husband Kimmel (who would be relieved on 16 December as part of the post-Pearl Harbor reaction), immediately commenced assembling a relief effort. Vessels included aircraft carrier Saratoga, heavy cruisers Astoria, Minneapolis, and San Francisco, nine destroyers, a troop transport, and an oiler, all to be commanded by Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher. The fleet had to wait for Saratoga to arrive from San Diego, and when it finally did put to sea on December 15, its pace was just 12 knots, which was the oiler’s top speed.

By December 21, the flotilla was still 500 miles from Wake, and Fletcher halted to refuel his ships. By this time Kimmel had been replaced by the Pacific fleet’s interim commander, Vice Admiral William S. Pye, until the Navy’s new overall commander in chief, Admiral Chester Nimitz, could arrive. After receiving Cunningham’s report that the Japanese had already landed, Pye became concerned about the ominous presence of the enemy aircraft carriers. On December 22, he was ordered to abort his mission and return to Pearl. The military managed to keep the failed rescue attempt a secret from the American public for the war’s duration.

Meanwhile, Japanese forces were feverishly preparing another assault. The next task force was commanded by Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe, with Kajioka in charge of amphibious landings. The aircraft carriers Hiryu and Soryu would participate along with six heavy cruisers and six destroyers. Transports would carry about 1,000 naval infantrymen. Carrier-borne warplanes would soften up the defenses prior to the landings, which were to be made at night to lessen the effectiveness of any of the now-feared shore batteries that might survive the air attacks. In hopes of taking the defenders by surprise, there would be no preliminary shelling. Two destroyer transports would be sacrificed by running them aground off the beaches. This way they could use their guns to support the landings with no fear of being sunk. Emphasis was to be given to getting the troops ashore quickly so they could create a strong foothold prior to being reinforced by 500 sailors. The fleet sailed from Roi-Namur during the small hours of December 21.

Blurring Day and Night

Back on Wake, American defenders staggered about, exhausted from 12 days of constant vigilance. Devereux later described “the foggy blur of days and nights when time stood still. The men’s days blurred together in a dreary sameness of bombing and endless work and always that aching need for sleep. I have seen men standing with their eyes open, staring at nothing, and they did not hear me when I spoke to them.” A civilian contractor, World War I veteran Nathan D. Teters, organized a crude but efficient delivery system that shuttled food to the men standing at their posts. Appreciative Marines dubbed it the “Dan Teters Catering Service.”

At 8:50 am on December 21, 29 Val dive-bombers escorted by 18 Zero fighters attacked Wake, doing little damage but indicating to the defenders the enemy had returned in force. There was no way the relatively short-range planes could have flown all the way from Roi-Namur—they had to have come from carriers. At 12:20 pm, another air raid destroyed Peale’s fire control equipment and its anti-aircraft battery.

The next day, another aerial attack force arrived at 13,000 feet. Captain Henry Freuler and 2nd Lieutenant Carl Davidson suicidally but unhesitatingly attacked the 33 dive-bombers and six fighters, flaming a Val and a Zero before the remaining Zeros riddled both Wildcats. Although wounded, Freuler managed to crash-land his wrecked plane on Wake’s airstrip. Davidson and his plane plunged into the ocean. Having lost all his aircraft, Putnam armed his remaining pilots and ground crewmen to fight as infantry.

Soon after nightfall the defenders noticed flashing lights out to sea, indicating the task force had arrived. At 2:30 am, the Japanese came ashore on Wilkes. Heavy fighting immediately broke out on the beach. The commander of the anti-aircraft gun telephoned Devereux of the landing, but when the enemy overran the flak pit the major lost contact with Wilkes.

“Enemy on Island—Issue in Doubt”

At this point the destroyer transports slammed into Wake’s offshore reef, opening an inaccurate fire and unloading troops. On a slight elevation next to the airstrip, 2nd Lieutenant Robert M. Hanna opened his three-inch gun on the nearest transport, quickly hitting it with 14 rounds that set it ablaze, illuminating the soldiers wading through the surf. Machine-gun nests immediately targeted these troops, cutting them down by the score. Still, enough reached the beach for them to make a desperate charge. Outnumbered, the Americans steadily fell back in hand-to-hand fighting until they were arrayed in a circle around Hanna’s gun, which now was pumping shells into the second transport.

A thousand yards west of this battle scene two landing craft had reached shore and engaged Lieutenant Arthur R. Poindexter’s force of 20 Marines and 14 civilians, steadily pushing them back. Additional barges were disgorging troops who fanned out across the islands as a torrential tropical thunderstorm commenced.

By 3 am, Wake was engulfed in a surreal nocturnal bloodbath so confused that neither side could determine the progress of the battle. The sole illumination came from explosions and lightning, but Devereux realized his forces were in dire straits. He managed to contact Peale (where the Japanese had not yet landed) by telephone and summon that island’s defenders to come to his assistance. He was hoping to establish a defensive perimeter across Wake near the command post and hold off the Japanese long enough for the relief flotilla to arrive. This was his last hope, but there was not enough time.

Cunningham managed to contact Honolulu by radio and inform Pye that the enemy had landed on Wake. Pye sent a chilling reply: “No friendly vessels in your vicinity nor will be within the next 24 hours. Keep me informed.” At 5 am, Cunningham radioed back: “Enemy on island—issue in doubt.”

The Fall of Wake Island

Dawn found Wake encircled by warships, now staying prudently out of range of the defenders’ 5-inch guns, not that many of them were still manned anyway. At 6:45 am, three destroyers eased closer to Peale in case they needed to support their troops with shellfire, but Kessler and his crew were still manning their 5-inch gun. After they scored several direct hits on the dead destroyer, the other three enemy vessels withdrew without even returning fire.

Carrier aircraft commenced strafing and dive-bombing without opposition from the now-overrun flak guns. On Wilkes, however, McAlister and Captain Wesley Platt led a counterattack on Japanese troops who thought they had the island secured. The combined Marine-civilian assault succeeded in annihilating the invaders already on Wilkes. Only two wounded survived; the other 98 were killed.

Back on Wake, Poindexter managed to rally 55 men and led them on an attack that temporarily drove the Japanese back eastward. Without communications, Devereux was unaware of these positive developments, and even if he had known, they represented only fleeting hope. Enemy soldiers had advanced past the aircraft revetments and reached the lagoon, cutting off Battery A from resupply for its dwindling ammunition stores. Marine aviator Henry Elrod, who had sunk a Japanese destroyer on December 11, reported for duty as a combat soldier. He personally cut down dozens of enemy attackers with a Thompson submachine gun before running out of bullets. He died attempting to fling a grenade point-blank into the engulfing wave of Japanese infantry. Elrod was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions on Wake.

Devereux got through to Cunningham on the phone and learned the bad news about the relief flotilla. Both men realized there was no way they could hold out for another 24 hours. There was little point in spilling more blood on either side, especially when delaying this particular Japanese force would make little tactical difference in the overall situation throughout the brand-new Pacific Theater of Operations. “Well, I guess we’d better give it to them,” Cunningham told Devereux, then returned to his quarters to shave, wash his face, and put on a clean uniform. A distraught Devereux transmitted the order personally to the defenders. “Don’t worry, Major,” Sergeant Bernard Ketner consoled him. “You fought a good fight and did all you could.” “It’s not my order, damn it,” Devereux replied.

With a mixture of despair and disbelief, the American forces surrendered. Devereux temporarily collapsed in a heap, but revived after a contingent of Marines marched past him in perfect parade formation. When a Japanese soldier tore down the American flag, Devereux held back his angry men. “Hold it,” he commanded. “Keep your heads, all of you!”

An Inconsequential Victory For Japan

The victors brutally mistreated their captives. Lieutenant Toshio Saito ordered five Marines beheaded in retaliation for the pugnacious American defense of their outpost. After the war, the four soldiers who carried out the executions were sentenced to life in prison but were paroled after nine years. Although he survived the war, Saito could not be located by war crimes investigators. He likely committed suicide. The rest of the surviving Marines were shipped to POW camps in China.

For the time being, the 100 civilian construction workers were interned on Wake Island. On October 7, 1943, Vice Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara had them machine-gunned to death. The reason he gave was that he suspected the workmen were using a clandestine wireless transmitter (which was never located) to pass military information to American aircraft. After the war, Sakaibara and 11 of his officers were hanged for the atrocity.

Forty-nine Marines, three sailors, and 70 American civilians were killed during the 16-day siege of Wake Island. The Japanese left few records of their own losses, but a conservative estimate is about 900 killed and 1,100 wounded. In a grim irony, the atoll played virtually no part in the rest of the war. It was one of many Axis-controlled outposts bypassed by the rebounding Anglo-American forces. Regularly pounded by the U.S. Army Seventh Air Force’s heavy bombers, Wake was cut off from resupply. Hunger and disease reduced the garrison. When he surrendered the island on September 4, 1945, Sakaibara had just 17 days’ worth of paltry rations remaining. Four hundred of his men were bedridden.

Remembering the Wake Island Defenders

Word of Wake’s gallant stand soon reached Washington. On January 5, 1942, Devereux’s 1st Defense Battalion and Putnam’s VMF-211 received Presidential Citations in absentia. In a radio broadcast, President Franklin D. Roosevelt eulogized the island’s defenders. “Some of these men were killed, and others are now prisoners of war,” said the president. “When the survivors of that great fight are liberated and restored to their homes, they will learn that 130 million of their fellow citizens have been inspired to render their own full share of service and sacrifice.”

After the war, the Navy erected on Wake a memorial to Major Putnam, who had been killed helping defend one of the 5-inch guns. The monument consisted of one of the battered Wildcat engines from VMF-211. It is still there today.

There is a legend that after the first repulse that Wake sent a message back to Pearl saying, “Send us more Japs”. Major Devereux denied having sent such a message, considering that they already had more Japanese than they could handle. What appears to have happened was that the junior officer that composed the message randomly added the phrases “send us” and “more Japs” to confuse Japanese codebreakers, and that when the message was decoded in Hawai’i they were put together as an actual part of the message.

It made headlines in US newspapers that allegedly infuriated the Japanese forces.

Major Devereux after the war wrote an excellent book called The Story of Wake Island which can be found online i.e. Amazon. It is an excellent read and in it he mentions during the battle that someone on one of the island’s radios kept transmitting “There are Japanese in the bushes, there are definitely Japanese in the bushes.” To the day he died he never found out who the Marine or civilian was. I’ve always wondered too.