By Flint Whitlock

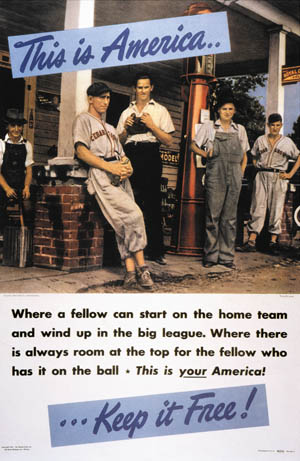

In the 1940s, war disrupted the lives of millions of people around the globe: fuel rationing, food rationing, shortages of all kinds, and, of course, the death and destruction that was visited on cities, nations, and whole populations. In entertainment and in sports during World War II, all the combatant countries tried to maintain at least a semblance of normality in order to keep up civilian morale. It was anything but easy.

In the United States during the 1930s and 40s, the major spectator sports were boxing, horse racing, major league baseball, and college football; although the National Football League started (as the American Professional Football Association) in 1920, it had not yet become America’s favorite athletic entertainment, and professional basketball was still decades away from achieving the popularity it enjoys today.

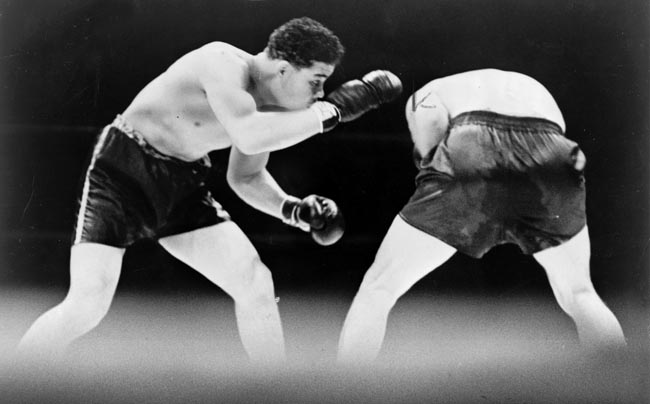

Boxing was hugely popular, especially after Joe Louis won a rematch and regained the world heavyweight championship against German Max Schmeling in 1938. (As an aside, Louis was later drafted and spent the war with the USO giving boxing exhibitions at bases around the country, while Schmeling joined the German paratroops and participated as a member of a mortar company in the 1941 invasion of Crete.)

Baseball’s War

The outbreak of war had a profound effect on the American sports scene. On July 8, 1942, eight months after Pearl Harbor, automobile and motorcycle racing were suspended entirely for the duration of the war due to gas and rubber rationing.

Deferments from the military draft that began in early 1942 were few and far between. As a result, many of the nation’s top athletes between the ages of 18 and 35—both college and pro—found themselves wearing uniforms of a different kind.

Five weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, baseball commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt for guidance on whether or not the upcoming major league baseball season should be canceled. For the good of public morale, Roosevelt advised that baseball should go on —if the talent were there.

Thousands of major and minor league players, including many of the game’s best-known stars, such as Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller, Ted Williams, Joe Garagiola, Yogi Berra, Red Schoendienst, Enos “Country” Slaughter, Bill Dickey, “Daffy” Dean, Ralph Kiner, Jackie Robinson, and Hank Greenberg, were trading in their flannels for khaki.

A number of ballplayers would also lose their lives in combat. Two major leaguers, Captain Elmer J. Gedeon, a U.S. Army Air Forces pilot and former player for the Washington Senators, died over France on April 20, 1944, while Marine 1st Lt. Harry M. O’Neill, (Philadelphia Athletics) was killed in action on Iwo Jima, March 6, 1945. Hundreds of minor league, semi-pro, and amateur players also died during the war.

As might be imagined, the loss of baseball’s top talent meant that less skilled players wore major league uniforms, and over-the-hill players came out of retirement to lend their services to the cause, even if just for a couple of years.

A Women’s Professional League

Because so many men had volunteered or were drafted into military service, a women’s professional league was formed in 1943 by William K. Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs. The league, made up of 15 Midwestern teams such as the Rockford Peaches, Kalamazoo Lassies, and Grand Rapids Chicks, was known as the All-American Girls Baseball League and was a combination of baseball and softball (the pitchers threw the ball underhand). The ball was the size of a regulation softball (12 inches), the pitcher’s mound was only 40 feet from home plate (rather than the standard 60 feet, six inches in the majors), and the bases were only 65 feet apart instead of 90 feet. More of a curiosity than anything, the women’s game inspired the 1992 film A League of Their Own, starring Tom Hanks, Madonna, and Geena Davis, but faded a few years after the war.

Sports in Japan

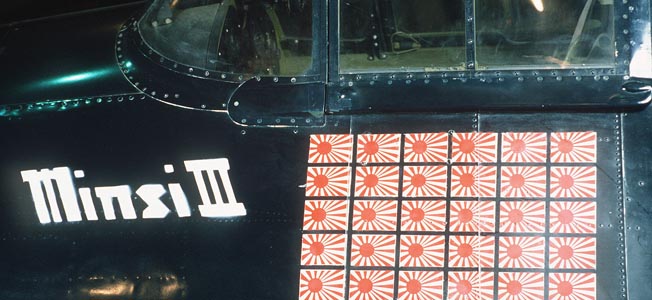

The Japanese had been introduced to baseball in the 1870s and, although it was the national pastime of their American foe, they embraced it through the war and afterward. At least 72 Japanese professional baseball players, called up to serve their country, gave their lives during the war.

The Japanese also had a professional soccer league and, after they invaded and occupied Korea and areas of the Far East, they incorporated Korean and other foreign teams into leagues in occupied areas.

Football’s Contribution: 1,000 Players and Coaches go to War

American football, too, felt the effects of the war and the draft. At the time, the college game was considerably more popular than the professional game, and thousands of college players soon found themselves serving Uncle Sam instead of their alma maters. Some 350 schools suspended football entirely for the duration of the war. These included Harvard, Princeton, Oregon, Stanford, Florida, and Mississippi State.

Because of fears of a West Coast invasion by Japan (and a U.S. government ban on large public gatherings on the West Coast for the duration), the 1942 Rose Bowl, scheduled to be held in Pasadena, California, three weeks after Pearl Harbor, was moved to the Duke University stadium in Durham, North Carolina (Oregon State beat Duke, 26-16.)

The National Football League’s ranks, too, were depleted as more than 1,000 players, coaches, and referees marched off to serve their country. Because of the shortage of players in 1943, the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Philadelphia Eagles merged to form the Steagles—a team that went 5-4-1 in its single season of existence. The merger ended prior to the start of the 1944 season, when the Steelers joined forces with the Chicago Cardinals, another struggling team. During that season the team was known as the Card-Pitt Combine and lost all 10 of its games; so inept was the team that some sportswriters began calling it the Carpets. The next year both Pittsburgh and Chicago operated separately.

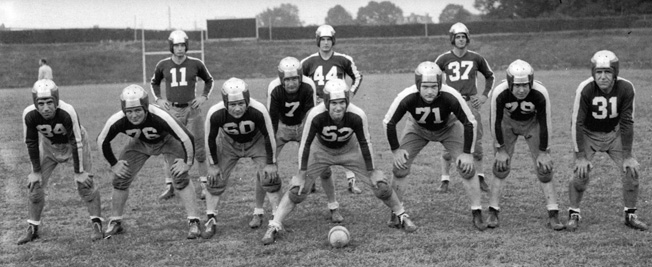

College and professional football’s loss was the military’s gain. Virtually every Army, Navy, Air Corps, and Marine base had a star-studded team that played regularly before large, football starved crowds. Their opponents were other bases and even college and NFL teams.

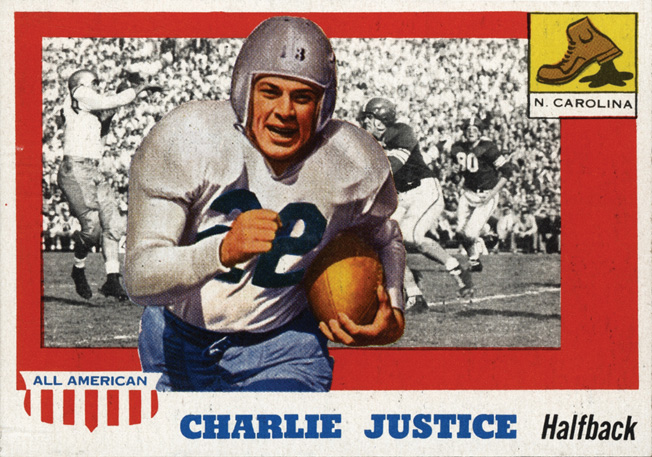

Of the base football teams, probably none was better than the Bainbridge Naval Training Station Commodores, located at Port Deposit, Maryland, on Chesapeake Bay. During their first season in 1943, and fielding a team with the likes of college and pro standouts Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice, Norm Standlee, Cecil Hare, Phil Ragazzo, Bill Dutton, Tom Noble, Gerry Ramsey, Red Hickey, and others, the Commodores defeated their opponents by a combined point total of 313 to 7. They beat one team, the Philadelphia Yellowjackets, 72-0.

Six hundred and thirty-eight soon to be famous NFL players, coaches, and owners joined the military during World War II, including George Halas, Otto Graham, Fred Levy Jr., Wellington Mara, Weeb Eubank, Sid Luckman, Andy Robustelli, Ernie Nevers, Chuck Bednarik, Tex Schramm, Bud Grant, Norm Van Brocklin, Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch, Pete Rozelle, and more.

Tom Landry, the famous head coach of the Dallas Cowboys from 1960-1988, dropped out of college to enlist. He served as the co-pilot of an Eighth Air Force Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber stationed in England and flew 30 missions, surviving a crash in Belgium.

Twenty-three NFL players would lose their lives during the war. Two professional football players—Maurice Britt and Jack Lummus—both earned the Medal of Honor.

The Bold Actions of Maurice Britt

Britt played end at the University of Arkansas and then for the Detroit Lions in 1941 before joining the Army. As an officer with the 3rd Infantry Division, Britt took part in three invasions: Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio. On November 10, 1943, while his division was battling furiously at Mignano, Italy, Captain Britt’s company was pinned down. He jumped up and started performing calisthenics in order to draw enemy fire toward him and away from his men.

His Medal of Honor citation reads, “During the intense fire fight, Lt. [sic] Britt’s canteen and field glasses were shattered; a bullet pierced his side; his chest, face, and hands were covered with grenade wounds. Despite his wounds, for which he refused to accept medical attention until ordered to do so by his battalion commander following the battle, he personally killed five and wounded an unknown number of Germans, wiped out one enemy machine gun crew, fired five clips of carbine and an undetermined amount of M1 rifle ammunition, and threw 32 fragmentation grenades.

“His bold, aggressive actions, utterly disregarding superior enemy numbers, resulted in the capture of four Germans, two of them wounded, and enabled several captured Americans to escape. Lt. Britt’s undaunted courage and prowess in arms were largely responsible for repulsing a German counterattack which, if successful, would have isolated his battalion and destroyed his company.”

Britt’s wounds resulted in the loss of his right arm, but his life was saved. After the war he ran a manufacturing company and then entered politics, serving as lieutenant governor of Arkansas.

Football’s Losses: From Iwo Jima to France

Jack Lummus, a Marine Corps company commander, had played college baseball and football at Baylor University, then joined the New York Giants as both an offensive and defensive end; he played in the 1941 NFL championship games against the Chicago Bears. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he joined the Marines and became an officer.

During the battle for Iwo Jima in February 1945, he was twice wounded by grenades but refused to be evacuated for treatment. Leading his men forward, 1st Lt. Lummus was confronted by an enemy machine-gun nest and knocked it out. While charging another, he stepped on a land mine that blew off both his legs. Mortally wounded, he still encouraged his men to advance before loss of blood claimed his life aboard a hospital ship.

At least two other former college football players lost their lives on Iwo Jima. Jack Chevigny played for Notre Dame in the 1920s and then coached the University of Texas team in the next decade. When war broke out, he joined the Marines and ended up at Iwo Jima, where he was killed.

Another player, Howard “Smiley” Johnson, played at the University of Georgia, then went on to the Green Bay Packers; he joined the Marines shortly after Pearl Harbor. He had earned a citation for conspicuous gallantry on Saipan in 1944 but lost his life on Iwo Jima.

Other NFL players, coaches, and front-office personnel who died during the war include Mike Basca, Charlie Behan, Keith Birlem, Al Blozis, Chuck Braidwood, Young Bussey, Ed Doyle, Grassy Hinton, Eddie Kahn, Alex Ketzko, Lee Kizzire, Bob Mackert, Frank Maher, Jim Mooney, John O’Keefe, Gus Sonnenberg, Len Supulski, Don Wemple, Chet Wetterlund, and Waddy Young.

Every one of them deserves special mention, of course, but 2nd Lt. Alfred C. Blozis, all six feet, six inches of him, is perhaps emblematic of them all. Serving with the 110th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division near Colmar, Alsace, France, Blozis sent a nine-man patrol into the snowy woods of the Vosges Mountains on January 31, 1945. Seven men returned, but two did not. So, Blozis went out alone to search for them. A short while later, the sound of a German machine gun was heard—a gun that killed the lieutenant who, just six weeks earlier, had played offensive tackle for the New York Giants in the NFL championship game.

Canadian Athletes in WWII

Canada’s national sport is ice hockey, and the war impacted that sport the way it affected all the others. Many brave Canadian athletes perished serving their country and the British Empire.

After war was declared, the six-team National Hockey League considered suspending operations, but the U.S. and Canadian governments urged it to keep going. Eighty NHL players served in the war, and two lost their lives in battle—Dudley “Red” Garrett and Joe Turner.

Garrett, a Toronto native who played for the New York Rangers, was called up and served in the Royal Canadian Navy. He died on November 25, 1944, when his supply ship was torpedoed by a U-boat off the coast of Newfoundland.

Born in Windsor, Ontario, Joe Turner played goalkeeper for the Detroit Red Wings in only one NHL game in 1942, but was killed in January 1945 while serving in the U.S. Army in Europe.

In Canada, both rugby and a version of American football have been played for over a century, and the sports, both at the collegiate and professional level, suffered many of the same problems as those in the United States. Because of the loss of so many players to the military, both the Western Interprovincial Football Union and the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union went so far as to completely suspend play during the war.

Sacrifice of the highest order was exhibited by Canadians. For example, one of Canada’s foremost gridiron players, Jevon “Jeff” Nicklin, who starred for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers from 1934-1940, joined the paratroopers, took part in airborne operations in the Normandy invasion, and was killed near Wesel, Germany, in March 1945 during Operation Varsity. In addition, seven members of the 1942 Grey Cup-winning Royal Canadian Air Force Hurricanes football club died in combat against the Germans.

As Laurie Prince, the daughter of RCAF Hurricanes punter Charlie Prince, put it, “One thing that my father very strongly believed was that you supported the group. Being a team member and in the war, that was the epitome of what they were doing, wasn’t it? To risk yourself for the bigger group.”

From Basketball Players to Warriors

Professional basketball was a relatively minor sport in the United States before World War II. One pro league, the National Basketball League, or NBL, was organized in 1937. A second league, the American Basketball League, or ABL, started in 1946. The two leagues would merge in 1949 to form the National Basketball Association. Like the rest of the sports scene, basketball contributed thousands of players to the war; some never came home.

One such player was Bob “Ace” Calkins, who captained the UCLA team in 1938-1939. When war broke out, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps and was serving as a navigator aboard a B-17 when it was shot down. He died from his injuries in an Italian prison camp.

Another basketball player who made the ultimate sacrifice was Edward C. Christi, the center and team captain of the U.S. Military Academy’s team from 1941-1944. He died in combat in Austria shortly before the war ended. West Point’s basketball arena is named in his honor.

The English Football Association: “Good for Morale”

In one sense, America was lucky. Its cities did not come under enemy attack. The same could not be said for the other major combatant nations—Britain, Germany, Japan, Russia, Italy, and others. In the large cities of these and other countries, football (i.e., soccer) stadia were often located in urban centers or close to industrial areas and thus became inadvertent targets.

In England, after Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and the British and French declared war on Germany, the English Football Association (or FA, the governing body of English soccer), canceled the rest of the season after only three games because of a ban on the assembly of large crowds. With immediate conscription, young Englishmen, including professional soccer players, were drafted into military service. And, with the season canceled indefinitely, the clubs ceased operations, bringing howls of protests from the fans.

To appease the fans, the FA relented and created seven regional leagues that provided some competition without placing undue strain on the nation’s railroad service that was needed to move troops and military goods (the government had imposed a 50-mile traveling limit).

But, because of fears of German bombing, the number of fans allowed to attend each game was limited to just 8,000. The government soon realized, as one historian wrote, that football “was good for morale and served the purpose of trying to keep life as normal as possible under the difficult circumstances. Gradually these attendance limitations were lifted, especially after the daytime bombings had stopped.”

Tom Finney, who played for Preston North End, was one of England’s best known footballers. He noted, “Wartime football was no substitute for the real thing but it did serve a purpose. There were restrictions galore and most clubs found their squads decimated through call-ups into the armed services, but the public passion for football won through.

“Sometimes matches were in doubt right up to kick-off as clubs tried desperately to recruit some guest players but, when the action rolled, it was good. Football provided the country with some much-needed escapism and, speaking as a player, it was thoroughly enjoyable—despite the bombs. After we had lost 2-0 at Anfield, our coach-ride home was caught up in an air-raid on Merseyside and that was a frightening experience by any standards.”

Bombed Stadiums of Britain

After the Luftwaffe’s first bombing raid on London, July 10, 1940, many historic English stadia were damaged or destroyed by German aerial bombing. After one 1940 raid, an unexploded bomb was found lodged in the stands at Stamford Bridge, home to the London club Chelsea. The bomb disposal unit was called, but they told the club there were hundreds of other unexploded bombs to deal with across London that had greater priority, so the team’s manager (head coach) Billy Birrell defused it himself.

Old Trafford, the famous Manchester United stadium, had its main grandstand destroyed in a 1941 Luftwaffe raid; the team played the rest of its home games until 1949 at the stadium of its arch rival, Manchester City.

Arsenal’s Highbury stadium, too, was badly damaged, forcing the Gunners to play their home matches at White Hart Lane—the home of their London rival, Tottenham Hotspur. The east grandstand at White Hart Lane was used as a temporary morgue for victims of the London Blitz. Aston Villa in Birmingham had its stadium commandeered by the Army, and thus the team was unable to play until 1942. London’s huge Wembley Stadium, too, was hit and damaged in 1944.

Many other stadia throughout England suffered extensive damage during air raids, including Sunderland, Hartlepool, Sheffield United, Southampton, Bristol City, Leicester City, and Plymouth Argyle, to name but a few. One Plymouth Argyle fan said, “There were some pretty angry football supporters ready to lynch Adolf Hitler for ordering the bombing of our football stadia if they could have caught him.”

In addition, with so many of their players in the service, some clubs had problems even fielding a full 11-man squad—some resorted to asking prior to kickoff if anyone in the stands would like to play! In anticipation of this, some young men brought their soccer boots with them to the games.

It was also sometimes difficult getting referees to the games. At least one game had to be called off before its conclusion because the referee had to report back to his Army barracks.

Another time, a game was suspended when a German bomber appeared overhead and everyone dashed for the air-raid shelter except for the referee, who was an antiaircraft gunner. He rushed to his gun position located nearby, strapped on his helmet, and began firing at the plane!

As might be expected, a number of British professional footballers became physical training instructors and did not see combat, while many others distinguished themselves on the battlefield.

Harry Goslin, captain of the Bolton Wanderers team, and 14 of his teammates enlisted in the Territorial Army and were assigned to the 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment. While serving with the British Expeditionary Force in France following the 1940 German invasion, Goslin destroyed four enemy tanks; he was given a field promotion to the rank of lieutenant.

Later, the footballers’ unit, the 53rd, was made part of General Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army for the invasion of Italy. On September 24, 1943, Lieutenant Goslin and his men landed at Taranto and began fighting their way northward along Italy’s east coast. On December 14, 1943, Goslin was hit by shrapnel and died of his wounds. His hometown newspaper mourned, “Harry Goslin was one of the finest types [of] professional football breeds. Not only in the personal sense, but for the club’s sake, and the game’s sake. I regret his life has had to be sacrificed in the cause of war.”

Other English footballers who lost their lives included Walter Sidebottom (Bolton), who drowned in November 1943 when his ship was torpedoed in the English Channel. Joe Rooney, who played for Wolverhampton, was killed in an air raid in Belfast in June 1941. Fred Fisher (Barnsley and Millwall) died in September 1944. Popular, red-haired William Imrie (Blackburn Rovers and Newcastle United) was in the Royal Air Force and lost his life during a raid in 1945.

Eight members of the Arsenal team died during the war, including Bobby Daniel, Sidney Pugh, Harry Cook, and Leslie Lack. Goalkeeper Bill Dean was killed in action with the Royal Navy in March 1942. Three other Arsenal players, Hugh Glass, Herbie Roberts, and Cyril Tooze, who all joined the Royal Fusiliers, also lost their lives.

And so it went for almost every British team. The names of the fallen are still memorialized on bronze plaques at most of the stadia.

Considered one of the greatest English soccer players of all time was the ageless Stanley Matthews, who played in the top level of the game for Stoke City and Blackpool until he was 50 and played for England’s national team 54 times. He was the only player ever knighted while still active. When war was declared, Matthews joined the RAF, but Sir Stanley’s reputation took a hit when it was learned that he and another well-known player, Stan Mortensen, sold items on the black market during the war.

In 1945, after Belgium was liberated, the two men were in Brussels with an FA Services team to play against local teams when they sold some rationed coffee and soap to a jewelry shop owner. Charged with “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline,” the pair admitted the allegations but received only a reprimand from their commanding officers. In spite of the incident, Matthews was also one of the first players to be inducted into the English Football Hall of Fame in 2002, two years after his death.

“Win or Die”: Italian Soccer in the 1930s

Sport in Europe continued its popularity in the 1930s despite the gathering war clouds. Mussolini’s Italy hosted soccer’s 1934 World Cup, with the home team defeating Czechoslovakia, 2–1, in Rome. And, as is well known, in 1936 Hitler used the awarding of both the Summer and Winter Olympic Games to Germany more for political than athletic purposes.

In 1938, the last soccer World Cup before the war, controversy came to the forefront. Prior to playing host country France in the quarterfinals, Italy was asked to field its team in white jerseys, as both teams’ colors were blue. Defiantly, however, the Italians, on Mussolini’s orders, dressed instead in black—a symbol of the Italian paramilitary fascists. Also on Mussolini’s orders, the Italian team members were instructed to hold their arms in the fascist salute throughout the playing of both nations’ national anthems and beyond. This they did until the frenzied anti-fascist French fans, outraged by the display, had screamed themselves hoarse.

To rub salt in the wound, the Italians won the match, 3-1, and then went on to beat Hungary, 4-2, to again become world champions. The Azzurri perhaps had an extra incentive when, before the championship game, Mussolini sent the Italian team a telegram stating, “Win or die.” The Hungarians were apparently aware of the threat facing the Italians because after the game the Hungarian goalkeeper, Antal Szabó, quipped that he had just saved 11 lives.

Sports in Nazi Germany

The Germans, too, like most of the rest of the world, had embraced soccer as their national sport and had had a thriving professional league since the early 20th century. The pummeling of German cities by the British and later by the Americans, however, brought great devastation to the country’s infrastructure. And, as with the other combatants, the athletes were pressed into military service. But the Nazi government decided that football was essential for the morale of the civilian populace, and thus, after banning teams with a communist or socialist connection, allowed the various teams and leagues to continue competition.

Jewish soccer teams and players also faced special scrutiny. As the Nazis imposed restrictions on the rights of Jews in Germany, clubs were compelled to expel their Jewish members. One club, known as Alemannia Aachen, however, defied the authorities by demanding that one of its Jewish players be released from prison; the Nazis, who were worried about a backlash that might harm their chances of hosting the 1936 Olympic Games, caved in. The retreat was only temporary, though, and after the Olympics German sporting clubs were purged of their Jewish members.

Across Germany, regional soccer leagues, known as Gau Ligen, were formed, and civilian clubs competed against military teams sponsored by the Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, and SS. By 1943, with fuel shortages growing worse and Allied air raids becoming heavier by the week, travel restrictions were imposed on teams and fans. With increasing manpower shortages, competition became ever more lopsided; scores of 10-0 or 15-1 were not uncommon. The greatest margin of victory came when Germania Mudersbach defeated FV Engen, 32-0.

Despite the round-the-clock Allied bombing, the diversion offered by soccer became more important than ever to the harried civilians. The 1943-1944 league championship game was initially called off by the authorities but then reinstated when fans protested. In that game, Dresdner SC beat SV Hamburg (made up mostly of Luftwaffe personnel), 4-0, in Berlin’s Olympia Stadium.

The end for Germany was drawing near, however. The Third Reich’s last recorded professional match took place between two Munich teams, FC Bayern and TSV Munich 1860, on April 23, 1945. Bayern won, 3-2, just three weeks before Germany’s unconditional surrender.

One of Germany’s most famous soccer players was goalkeeper Bernhard “Bert” Trautmann. Like Max Schmeling, Trautmann had joined the Luftwaffe and volunteered for paratrooper duty. He fought on the Eastern Front for three years, where he earned five medals, including the Iron Cross. Later transferred to the Western Front, he was captured by the British and incarcerated in a prison camp in England.

After the war, Trautmann declined to be repatriated to his home country and stayed in England, where he played for local amateur teams until he was signed in 1949 by Manchester City in the league’s highest professional division. Not all of City’s fans were pleased by the signing of a former enemy paratrooper, however, and 20,000 once turned out in protest. But his solid play in goal eventually earned acceptance and respect; he played in all but five of the club’s next 250 matches.

Sports in the POW Camps

Prisoners of war, no matter what their nationality, were usually able to obtain sports equipment and organize contests behind barbed wire. One British soldier, Len Murphy, a prisoner of the Germans, recalled, “One day quite a number of us were back in camp early and decided to have a game of football. I was in goal when the German Sergeant Major who had been watching decided to take part, pushing me out of the goal and taking my place. Well, the lads all thought this was funny and after a while decided to kick the ball at him. After several [shots], ‘Peg Leg’ as he was known, pulled out his revolver, pointed it at the lads and said ‘The next one who tries to score will be shot!’ We all thought it rather funny, but thought better of it. We did not know that he was joking!”

“Match of Death”

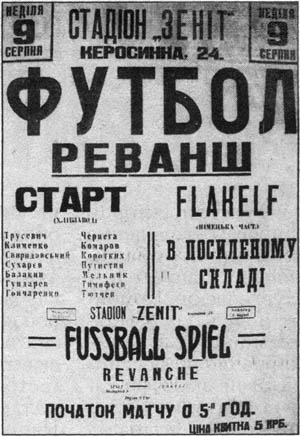

Perhaps the most famous wartime game that involved the Germans was called the “Match of Death.” In August 1942, during the Nazi occupation of the Ukrainian city of Kiev, a team composed of Luftwaffe antiaircraft gunners calling themselves Flak Elf (Antiaircraft Eleven), many of whom were ex-professional players, faced off at Zenit Stadium against a team called FC Start, made up of malnourished Dynamo Kiev players.

The two teams had earlier played each other, with the Kiev team winning by a huge 5-1 margin. This time there would be no embarrassing defeat for the visitors. Before the match, an SS officer told the Kiev team that they would lose or face the consequences. To ensure a German victory, a German referee presided over the match and implied to the Kiev players at the pregame coin toss that they must give the Nazi salute and also that it would be wise for them to lose.

The German players gave the customary stiff-armed salute and shouted, “Heil, Hitler!” while the FC Start players put their hands to their chests proclaiming the Soviet slogan, “Physical culture, hooray!” The local fans cheered wildly.

Once the game began, the Flak Elf team began fouling its opponents with vicious tackles, trips, shoves, elbows to the face and ribs, and every other tactic prohibited by the laws of soccer; the referee ignored the fouls. After the FC Start goalkeeper had been brutally fouled, the Germans scored. Not long thereafter, FC Start scored the equalizer, then another and another to go into the locker room at halftime up 3-1. The local spectators were delirious with joy while the Germans were fuming.

During the interval, a Soviet collaborator with the Nazis entered the Kiev locker room and addressed the team, telling them that they had better lose if they knew what was good for them. Another visitor, an SS officer, made threats against their lives and their families if they should win.

Undaunted, the Ukranians came out for the second half and scored two more goals. The Germans scored, too, and the game ended 5-2.

The Gestapo’s Retribution

What happened afterward has been shrouded in legend and mystery. Some sources say that the entire FC Start team was taken to Kiev’s Babi Yar ravine, where over 100,000 civilians, mostly Jews, had been murdered by the Nazis and their bodies dumped, and shot while still in their soccer uniforms.

Another more accurate story has it that the Gestapo showed up at the Kiev bakery where the team members worked, arrested them, and took them off to headquarters where they were tortured in hopes of getting them to confess that they were Soviet spies and saboteurs. No one cracked under the pressure, but the sister of one player, Nikolai Korotkykh, exposed him as a former NKVD officer. He died during torture, becoming the first victim of the “Match of Death.”

The remaining 10 players were sent to a slave labor camp. When partisans attacked the Germans in 1943, the camp commander gave the order to kill three of the players; their bodies were thrown into the Babi Yar ravine. Hearing about this atrocity, three other players escaped from the camp and hid in the city until it was liberated by the Red Army in late 1943.

After the war, one of the surviving Kiev players said, “A desperate fight for survival started which ended badly for four players. Unfortunately they did not die because they were great footballers, or great Dynamo players…. They died like many other Soviet people because the two totalitarian systems were fighting each other, and they were destined to become victims of that grand scale massacre. The death of the Dynamo players is not so very different from many other deaths.”

In 1981, Hollywood made an entertaining but wildly fictitious movie about the incident, titled Victory!, directed by John Huston, starring Sylvester Stallone, Michael Caine, and Max von Sydow, and featuring cameo appearances by the great Brazilian star Pelé and Bobby Moore, the captain of England’s 1966 World Cup winning team.

A Legacy Felt to This Day

Decades after the end of the war, reminders keep popping up at local venues in Europe. In 1998, an unexploded 1,000-pound bomb was discovered a few feet below the center of Borussia Dortmund’s playing field during reconstruction work there. In 2002, while remodeling Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, workers found a 500-pound bomb beneath a section of the stands; it was safely defused. In Munich two years later, two bombs were found at the construction site for a new soccer stadium, the Allianz Arena, and detonated by munitions experts in a controlled explosion.

While the VfB Stuttgart stadium was being remodeled in 2009, 18 unexploded bombs were found at the construction site, and in 2012, workers came across an American 500-pound bomb beneath one end of Munich’s 101-year-old Grünwalder Stadium.

Perhaps the most lasting and frightening connection between war and sport is what happened in deepest secrecy beneath the now demolished stands of the University of Chicago football stadium, where college football hall of famers such as Jay Berwanger, the first Heisman Trophy recipient, Paul Des Jardin, and Walter Steffan once played for legendary coach Amos Alonzo Stagg. It was there on December 2, 1942, that the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction took place under the watchful eyes of physicist Enrico Fermi and other scientists. As a result, the atom was unleashed, and civilization has never been quite the same.

It has been said that enjoying sport in the midst of war verges on the sacrilegious, akin to laughing during a serious sermon in church. Sport, these critics say, has no business intruding on the life-and-death issues that war brings —that intensely focusing on victory on the battlefield and nothing less should be the ultimate and undiluted effort of every man and woman in a nation at war.

Yet, such a singular focus obscures the true value of sport and other diversions during a time of great stress—to take one’s mind off the grimness, even for just a few hours, and remind everyone of the pleasures of peace and the joys of living.

At a match on Easter Saturday 1939, Bolton Wanderers captain Harry Goslin made a speech urging spectators to join up. The following Monday he and the entire first team joined the d Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. Players from a number of other clubs also joined up together, including Liverpool FC, whose players formed a club section in the Kings Regiment. Harry Goslin was killed while serving in Italy in December 1944.

Thank you for this amazingly insightful piece. Currently serving in the US Navy and sport has been a catalyst for me to increase the morale of my shipmates and myself. I really enjoyed reading this, and I was blown away by the bits on German sports during the war, I did not know about this.