By William Welsh

During the infamous Black Week of December 1899, the proud British Army suffered three consecutive bloody defeats in southern Africa. In each of the clashes, Boer citizen-soldiers, called burghers, held fast to their defensive positions and repelled poorly executed attacks by the supposedly better-trained British forces. The shocking victories at Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso lifted Boer morale while crushing British hopes for a quick, decisive victory against the outgunned and outnumbered enemy.

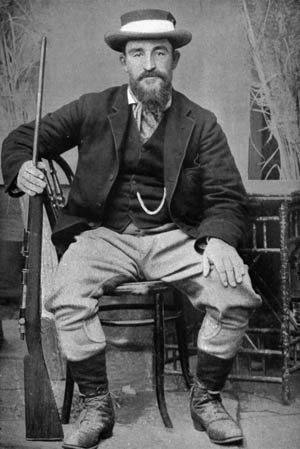

Ironically, a key Boer leader did not participate in any of the Black Week battles. Instead, newly promoted General Christiaan de Wet journeyed by horse and railcar from the eastern front in Natal to the western front in the Orange Free State, where President Marthinus Steyn wanted him to lead two Boer commandos into battle. The Boer fighters at Magersfontein were unacquainted with De Wet and unimpressed by him. De Wet lacked the piercing gaze of Assistant Commandant-General Louis Botha or the paternalistic demeanor of Commandant-General Piet Joubert. Of middle height, with slumping shoulders and kind eyes, De Wet looked more like a station master or a bank clerk than someone capable of derailing the best-laid plans of Great Britain’s most celebrated generals.

De Wet’s Triumph at Nicholson’s Nek

Despite his unprepossessing appearance, De Wet had a keen mind for strategy and a quick eye for tactics. When the Second Boer War erupted in 1899, he was working his farm in the Orange Free State. In keeping with the state’s injunction to raise large families to populate the Boer republics, the 45-year-old farmer and his wife were busy raising 16 children of their own. De Wet, like most Boers, was no stranger to warfare. He had fought alongside the Boer forces from Transvaal that defeated the British in the Battle of Majuba Hill in 1881 during the First Boer War.

In late September 1899, the Boers mobilized and deployed substantial forces on the borders of Cape Colony and Natal. On October 9 they issued an ultimatum to Great Britain to cease interfering in the internal affairs of the Boer republics. Two days later they invaded British-held Cape Colony and Natal.

De Wet did not participate in the initial action in Natal because the Free State forces mobilized more slowly than their northern neighbors in Transvaal. His 500-man commando arrived on the eastern front after the British forces had withdrawn from Dundee and retreated to Ladysmith. In an effort to keep the Boers from encircling Ladysmith, British Lt. Gen. Sir George White dispatched units under his command to drive the Boers from several key hills, or kopjes, north of the town. Lt. Col. Frank Carleton, given orders to occupy Nicholson’s Nek, left Ladysmith at 10:30 am on October 30 at the head of a column comprising the 1st Battalion of Gloucesters, 1st Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, and the 10th Mountain Battery.

The broken ground and high country of northern Natal made for tough going. At one point, artillery mules stampeded, and the noise alerted the Boers in the vicinity that the enemy was on the move. Carleton failed to reach his objective before nightfall. Fearing that he would be ripe for attack if he camped on low ground at the base of the gap, Carleton ordered his men onto Tchrengula Mountain south of the pass, where they hastily constructed breastworks from loose stones.

The Boers in the vicinity planned to attack Carleton wherever he camped. At daybreak they struck from three sides. De Wet led the northern prong of the attack along the ridgeline. During their advance, the Boers killed or drove off most of Carleton’s pickets before one company of British soldiers raised a white flag to surrender. Believing that the entire British force was preparing to surrender, the Boers emerged from cover. Carleton, realizing what had happened, refused to continue the fight, preferring to surrender his entire force rather than be accused by the enemy of violating a white flag. It was a heady triumph for De Wet and other Boer officers on the scene, who managed to lead away 954 British soldiers with very little bloodshed.

The Army Under Roberts’ Command

The day after the action at Nicholson’s Nek, General Sir Redvers Buller, the commander in chief of British forces in South Africa, arrived in Cape Town along with the 47,000-strong British 1st Army Corps. While en route he wired orders to White instructing him to abandon Ladysmith and take up a new position behind the Tugela River. Upon his arrival, Buller learned that White had disregarded his orders and was trapped in Ladysmith. Immediately, the relief of Ladysmith became one of Buller’s top priorities, along with the relief of other besieged British forces at Kimberley and Mafeking. Buller personally led a rescue force to relieve the 10,000 British troops bottled up inside Ladysmith and clear northern Natal of the Boers.

After several weeks of hard marching, three British columns closed with the enemy. In the center, Lt. Gen. Sir William Gatacre hoped to dislodge Boer forces and capture the railway junction at Stormberg. Following a bungled night march, his troops made a weak attack the morning of December 10 against a Boer army entrenched on high ground. After the initial attack failed, Gatacre ordered his troops to withdraw, but 600 did not get the order in time and subsequently surrendered.

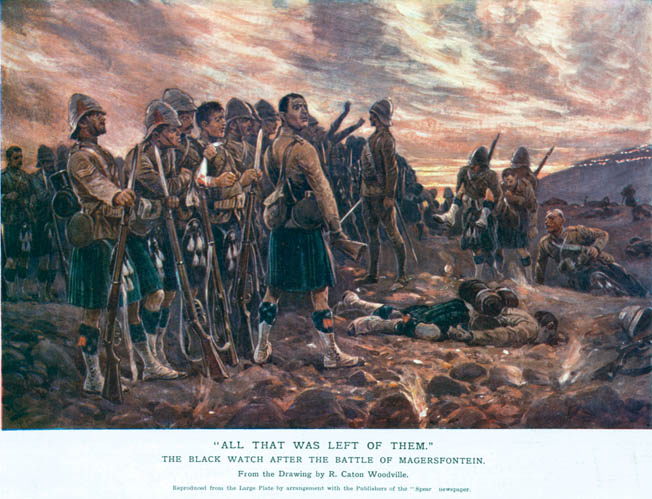

The next day a much larger battle occurred to the west, where Lt. Gen. Lord Methuen attacked an entrenched Boer force at Magersfontein and was thrown back with heavy losses. The last, and perhaps most significant, defeat of Black Week occurred at Colenso, when Buller ordered a frontal assault against Boers on the north bank of the Tugela River. It, too, ended in failure. When news of the shocking string of defeats reached London, the British minister of war, Lord Lansdowne, ordered his friend and colleague Lord Frederick Sleigh Roberts, who was serving in India, to replace Buller as commander in chief of British forces in South Africa.

Roberts planned to march north to seize the Boer capitals at Bloemfontein and Pretoria. Of the nearly 100,000 British troops in Africa by that time, Roberts had half under his direct command. For his initial advance, Roberts would lead a 37,000-man corps north along the Western Railway to relieve Kimberley. Once he took Kimberley, Roberts would be in a good position to outflank Boer Commandant-General Piet Cronje at Magersfontein.

Roberts took command of his army in mid-February at Waterval Drift on the Riet River. The British found when they tried to move their supply train through the drift on February 15 that the soft mud on the riverbanks made for an extremely poor crossing. While the supply train of 200 wagons slowly made its way through the drift, Roberts marched off to the northwest with Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Colville’s 9th Division and crossed at Wegdraai Drift. The teamsters responsible for the supply train allowed the oxen, which had struggled through the mud at Waterval, to graze and rest on the north bank before resuming their march. Five hundred men were assigned to guard the supply train until it rejoined the corps.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John French led 5,000 cavalry on a wide sweep around Cronje’s forces at Magersfontein. After a three-day ride, the British entered Kimberley on February 15. While his exhausted cavalry was given a hero’s welcome in Kimberley, Roberts’s infantry divisions crossed the Riet River and began fanning out across the veldt. In response, Cronje’s force began a slow retreat toward Bloemfontein.

Ambush at Waterval Drift: “A Gigantic Capture”

On that same day, De Wet swooped down on the lightly defended British supply train at Waterval Drift with a force of 1,000 mounted commandos. About mid-morning, the general ordered several long-range guns atop nearby kopjes to open fire on the British position. As the shells crashed into the dirt around them, the badly surprised teamsters attempted to drive as many oxen as possible into the drift, where they hoped the steep banks would protect the animals from shrapnel. Meanwhile, others rushed to the unhitched wagons and began hastily to unload crates to serve as makeshift breastworks for the impending attack.

Observing that the British seemed determined not to give up their supply train without a fight, De Wet ordered his dismounted riflemen to attack. As the fight got under way, the oxen became more difficult to control and, to the consternation of their handlers, stampeded toward the Boer lines. Despite the loss of the oxen, the British infantry defending the supply wagons refused to surrender. The fighting continued well into the afternoon, while the defenders dispatched pleas to Roberts to send reinforcements. In response, Roberts eventually dispatched two battalions of infantry and an artillery battery. He ordered Maj. Gen. Charles Tucker, commanding the 7th Division, to assess the situation and report back to him.

The reinforcements were unable to rescue the besieged forces before De Wet made off with 170 wagons filled with supplies. He also captured or drove off 1,600 oxen that the British needed to haul supplies. “It was, indeed, a gigantic capture; the only question was what to do with it,” De Wet wrote in his memoirs. The oxen proved as difficult for the Boers to control as they had been for the British, and De Wet’s command lost considerable time rounding up scattered animals and dragging off their booty.

Cronje’s Defeat at Paardeberg

Roberts’s primary objective was to capture Bloemfontein. He knew that to achieve his goal required defeating Cronje’s 4,000-man army. The latter’s withdrawal along the north bank of the Modder River was agonizingly slow. Cronje believed it necessary to protect his five-mile-long supply train, despite the urging of his subordinates to abandon the train. Cronje did not get far before he learned that British cavalry had gone before him and assumed a blocking position until Roberts’ infantry could catch up. Rather than abandon his wagons and cut his way out, Cronje stubbornly entrenched at Paardeberg to await his fate.

On February 18, the British attacked in force. While Roberts’s infantry suffered more than 1,200 casualties in a senseless frontal assault, British artillery and rifle fire decimated the horses that Cronje’s men rode, making escape difficult if not impossible. In the days that followed, the British pounded Cronje’s position with shells from more than 100 guns encircling the Boers. With Cronje’s men no longer able to get away, it was left to De Wet to assist his superior. He promptly ordered his men to mount up.

By late afternoon, De Wet’s force managed to reach a position six miles east of Paardeberg on the south bank of the Modder River. After surveying the enemy’s position atop a ridgeline, De Wet ordered his men to dislodge the British from high ground and help Cronje break out from the trap. At dusk, De Wet led a force of about 500 Boers onto a prominent kopje known as Horse Hill, surprising and capturing 100 enemy cavalry. He sent word to Cronje of the possible escape route, but by then Cronje seemed incapable of reaching the life vest thrown out to him.

For three days De Wet held the position, but only a trickle of men from Cronje’s army took advantage of the opportunity to avoid capture. On February 21, De Wet could no longer hold out against British efforts to recapture the ridgeline, and he withdrew his men. Six days later, Cronje surrendered his luckless force to the British. With Cronje in captivity, the difficult task of leading the Free State forces fell to De Wet.

A Strategic 12-Day Leave of Absence

After the debacle at Paardeberg, Boer politicians and generals held a council of war at Kroonstad, 100 miles north of Bloemfontein. General I.E. Ferreira initially was chosen to succeed Cronje as commandant-general, but after Ferreira was accidentally killed by one of his sentries, De Wet was given command of the state’s forces.

Believing that Bloemfontein would fall in a matter of days, Boer leaders plotted a strategy to distract Roberts and slow his northward progress. Generals Koos De la Rey and Louis Botha would ride toward Bloemfontein in an attempt to lure Roberts into battle, while De Wet was to swing southeast to link up with a force of 5,000 commandos led by Jan Hendrik Olivier, who was rapidly retreating from a position behind enemy lines along the Orange River.

Roberts’s army marched unopposed into Bloemfontein on March 10. The British commander paused to deal with a number of problems. The majority of his troops had been drinking contaminated water and, as a result, field hospitals were overcrowded with men suffering from dysentery. Another reason for the British delay was a lack of supplies. Having lost a considerable number of oxen at Waterval Drift, Roberts had to wait for the arrival of fresh animals to pull his supply wagons. While waiting, Roberts issued a proclamation to Free State burghers promising to leave them unmolested if they turned in their firearms and took an oath of neutrality.

Knowing that the British were unlikely to resume their advance until they had replenished their supplies, De Wet granted his men a 12-day leave of absence to boost morale. The number that reassembled on March 25 at the designated meeting place on the Zand River exceeded De Wet’s wildest expectations. The column rode to Brandfort, just north of the position held by Roberts’s army.

Sannah’s Post

Less than a day’s march east of Bloemfontein lay the city’s waterworks. They were located adjacent to a way station known as Sannah’s Post on an unfinished rail line connecting Bloemfontein with Thabanchu. De Wet resolved to overrun the facility’s meager guard of 200 men and destroy the pumping station to deny the enemy the clean water essential to the health of its troops. De Wet’s plan called for dividing his forces into two separate groups. He would take 350 men and move west into position along the banks of Korn Spruit, a tributary of the Modder, while his brother Piet De Wet made a full-scale assault across the Modder from the east with the remaining 1,150 burghers. If all went according to plan, the outnumbered British garrison would be surprised and captured before it could be reinforced.

While De Wet was assembling his men for the raid to capture the Bloemfontein waterworks, British Brig. Gen. Robert Broadwood was leading a 1,700-man column back to Bloemfontein to spread word of Roberts’s amnesty proclamation throughout the Free State. Broadwood’s force comprised two cavalry regiments, a brigade of mounted infantry, and two batteries of horse artillery. On his return to Bloemfontein, he planned to escort 92 wagons consisting primarily of English refugees with a few Boer “hands-uppers” who desired protection. Broadwood spent several days distributing leaflets, but he decided to withdraw after he learned that a sizable Boer force was retreating in his direction. He wired Roberts on March 30 that he planned to camp at the waterworks on his return march to Bloemfontein.

Broadwood’s force began arriving at Sannah’s Post at midnight on March 30. A small mounted escort arrived first. The main force splashed through the Modder about 3:30 am, and was followed 30 minutes later by U and Q Batteries. Exhausted from the bad roads and repeated skirmishes with the lead elements of Olivier’s column, the British troopers bedded down beside the refugee wagons. The garrison commander wrongly assured Broadwood that the enemy was not in the immediate vicinity, and Broadwood decided not to post sentries. It was a serious mistake.

As his main force approached the Modder just before daybreak, De Wet’s scouts informed him that a mounted British column had arrived at the waterworks during the night. Although the odds were now even, De Wet remained confident that he held the upper hand. Boer forces moved into position in the kopjes on the east bank while the commandant-general took his smaller force west to assume a blocking position at Korn Spruit. Once they reached Korn Spruit, the burghers spread out in ravines along both sides of the wagon road where it entered the drift.

Broadwood dispatched several patrols before daybreak with instructions to ford the Modder and search for signs of enemy activity. The majority of the patrols had nothing to report, but a lieutenant leading one patrol reported enemy gunfire. Believing this to be an isolated incident, Broadwood sent out no additional patrols. One significant incident might have forewarned him of the enemy presence. Roberts’s chief of scouts, American-born Frederic Russell Burnham, was patrolling the area at daybreak and spied Boer forces massing for an attack. He climbed a kopje and began frantically waving a red handkerchief in an attempt to signal Broadwood’s men. Burnham managed instead to catch the attention of the Boers, who subsequently took him prisoner.

Catching the Wagon Train

At first light, the burghers at Korn Spruit spotted a wagon on the east side of the stream just above the drift. Standing alongside the wagon was a small group of native tribesmen tending some sheep and cattle. The burghers interrogated the tribesmen and learned that the wagon belonged to a hands-upper from Thabbanchu. The tribesmen said the farmer intended to sell his livestock to the British Army once he arrived in Bloemfontein. The burghers promptly took custody of the wagon and livestock.

Shortly after the British patrols returned, shells crashed into the British camp at the waterworks. The barrage caught the British completely by surprise. Dodging shrapnel as best they could, the British soldiers dove for cover. While they knew the fire was coming from the far side of the Modder, they had no way of judging the size of the threat or of determining the exact location of enemy forces. The Boers had done an exemplary job of concealing themselves among the kopjes that lined the east bank.

After the initial shells rained down, the burghers opened up with their Mausers, making it impossible for the British to remain on the open grassland around the waterworks. Broadwood mistakenly assumed that he was under attack from Olivier’s 5,000-strong force, and decided that his best course of action was to withdraw as swiftly as possible to Bushman’s Kop, where he could dig in and await reinforcements. The wagons started toward Korn Spruit at dawn, and Broadwood ordered his troops to saddle up and follow the wagon train.

A large number of wagons driven by local refugees and escorted by about 200 British soldiers entered the drift at Korn Spruit. The refugees had heard gunfire erupt in the vicinity of the waterworks and, in response, drove their wagons as quickly as possible toward what they believed was safe ground. “The result was a scene of confusion,” De Wet wrote. “Towards us, over the brow of the hill, came the wagons pell-mell, with a few carts moving rapidly in front.”

As the wagons rumbled down into the drift, De Wet’s burghers sprang from well-concealed positions and shouted, “Hands up!” The soldiers were rounded up and disarmed. At this point, De Wet ordered the refugees to form a single line, drive through the spruit, and wait on the opposite bank. The refugees were warned that they would be shot if they made any attempt to signal their predicament to the British soldiers on the other side.

“Dismount. You are Prisoners.”

In the meantime, large numbers of disorganized British troops on foot and horseback began streaming into the drift. Having returned to their concealed positions, De Wet’s burghers once again sprang from cover and ordered the British soldiers to throw down their weapons. Confusion reigned. De Wet was enraged by his troops’ inability to disarm the British in an efficient manner. Rather than simply throwing the captured rifles out of reach of the prisoners, the soldiers sought their commander’s advice at every turn. “The burghers kept on asking, ‘Where shall I put this rifle, General? What have I to do with this horse?’ This sort of thing sorely tried my hasty temper,” De Wet wrote.

Shortly after the shelling began at daybreak, Major Edmund Phipps-Hornby, commander of Q Battery, was awakened by one of his gunners, who asked him in a shaky voice whether the battery should limber up and withdraw. Phipps-Hornby decided to bring some of the guns into action, but it quickly became apparent that the 12-pounders were substantially outranged by the Boer guns. Realizing that effective counterbattery fire was impossible, Broadwood ordered both batteries to withdraw west. Broadwood told Major P.B. Taylor, commanding U Battery, to proceed first, with Phipps-Hornby to follow. The officers immediately set off in the direction of Korn Spruit.

Taylor’s battery arrived at the drift first. Broadwood had instructed Taylor to cross the spruit and unlimber his battery atop a ridge on the opposite bank to provide cover for the withdrawal. When Taylor reached the edge of the drift, De Wet stepped forward and announced calmly: “Dismount. You are prisoners. Go to the wagons.” In no position to argue, Taylor’s men allowed themselves to be led away. In the confusion that followed, Taylor managed to remount and ride to safety.

From his position in the rear of the column, Phipps-Hornby watched as Taylor’s battery drew up alongside a row of wagons halted on the east rim of Korn Spruit. Phipps-Hornby surmised that U Battery was stopping to allow the wagons to cross first. Suddenly a gunner from U Battery came running toward Q Battery, shouting: “We are all prisoners! The Boers are there! They are in among the convoy and among the guns!” Taylor rode up next and verified the gunner’s report.

Realizing at once that his battery was exposed to the enemy’s deadly accurate rifle fire, Phipps-Hornby ordered the limber drivers to wheel to the left and make for the outbuildings at the railroad station. With the keen eye of an artillery commander, he had spotted a low ridge 70 yards in front of the station where he planned to unlimber his guns and make a stand.

Retreat of the Guns

Seeing the second British battery riding away from the drift, De Wet ordered his men to open fire. The roll of gunfire startled the horses of U Battery, and they immediately bolted in all directions, causing more confusion in the Boer ranks. To alleviate the situation, burghers began firing at the panicked horses in an effort to silence them. Boer rifle fire also ripped into the horses and men of Q Battery. One crew was completely decimated before it could withdraw; two wagons carrying badly needed ammunition overturned and were abandoned by the rest of the battery.

The commander and men of Q Battery managed to get five of their guns to the low ridge despite the unabated hail of bullets. Together with the one gun crew that escaped from U Battery, Phipps-Hornby had virtually a complete battery in hand. Although the Boers were within range, the flat trajectory of the British guns made it difficult to hit the burghers deployed at a higher elevation along the edge of the drift. In the subsequent duel between British artillery and Boer riflemen, the Boers quickly gained the upper hand. In a short period of time, Q Battery lost 38 of its 50 officers and gunners. Besides Phipps-Hornby, the only other officer left alive was Captain Gardiner Humphreys. At 10 am, Phipps-Hornby ordered the guns withdrawn to the relative safety of the station.

Hoping to save as many guns as possible, Phipps-Hornby managed to corral some men who had been crouching behind a nearby stone wall to help remove the guns from the ridge. When the men ignored his initial pleas for assistance, Phipps-Hornby berated them as cowards. “I gave them the rough edge of my tongue, and said I would shoot any man who didn’t get out,” he wrote later. “Go out and fight—or come and help me.”

Ten dismounted cavalrymen left the safety of the stone wall to assist. The motley group of gunners and dismounted troopers had to make several trips between the ridge and the station buildings to drag the guns to safety. While trudging up the slope, they leaned forward into the enemy fire as if facing a heavy wind. The calm courage exuded by Phipps-Hornby and Humphreys sustained the men. When Humphreys’s stick was knocked from his hand by an enemy bullet, he nonchalantly bent down and picked it up before continuing at a casual pace back toward the guns.

Rewards and Reprimands for the British Officers

Phipps-Hornby also showed his mettle. When one of Broadwood’s aides suggested that he retire to the relative safety of the station buildings, he matter-of-factly replied, “Perhaps it would be as well, but I have been here some hours now.” In the process of withdrawing the guns, a number of the volunteers and artillerymen were felled by the unrelenting Mauser fire. The carnage was overwhelming. Nevertheless, Phipps-Hornby and his men managed to pull three guns and a substantial amount of equipment to safety before breaking off the task. They then hitched the three guns to limbers parked behind the station buildings and withdrew south, fording the spruit and driving hard for Bloemfontein.

Phipps-Hornby’s escape was part of the hurried retreat by Broadwood’s entire command from Sannah’s Post. When the majority of Broadwood’s mounted troops reached Korn Spruit, he ordered them to cross the spruit above and below the position held by De Wet and his men. The numbers streaming past the Boer position at Korn Spruit were substantially larger than the Boer contingent holding the drift, and De Wet ordered them to stand fast and make no attempt to pursue the British. “We fired at them as they passed and took several more prisoners,” De Wet wrote. “Had I but commanded a larger force, I could have captured every one of them.”

When Phipps-Hornby arrived at Bloemfontein later that day, he sought relief for his frayed nerves by tossing back three glasses of whiskey in quick succession. Physically and emotionally drained, he broke down and wept. Word quickly spread among the garrison of Q Battery’s resistance and the harrowing withdrawal of its guns under enemy fire. Phipps-Hornby, another officer, and three gunners received the Victoria Cross for their service that morning. Broadwood, conversely, was severely reprimanded in private by his superiors for his actions at Sannah’s Post, but officially he was exonerated of any responsibility for the debacle.

428 Prisoners and 117 Wagons

De Wet’s haul from the ambush was substantial. He had captured 428 prisoners and 117 wagons, and he had recovered seven of the nine guns left on the battlefield. As the action drew to a close in the early afternoon, the burghers gathered the spoils in preparation for transporting them to safety in the Transvaal. De Wet decided to take 800 men and continue raiding south, leaving the remainder to escort the wagons, guns, and prisoners north. On April 3, De Wet’s raiding party successfully attacked a British convoy under the protection of the Royal Irish Rifles near Reddersberg. After an intense fight that lasted the entire day, the Boers prevailed and accepted the surrender of 546 men.

Detaching part of his force to march the prisoners north, De Wet and his remaining men rode to Wepener, where they boldly laid siege to a much larger force numbering 1,900 men led by Maj. Gen. E. Brabant. The unit, known as Brabant’s Horse, was made up of Afrikaners from Cape Colony, and the idea that they had enlisted to serve the Crown enraged De Wet. He undertook a siege of the town that lasted more than two weeks before breaking off the action and returning north.

Bold as it was, De Wet’s raid was only a minor distraction to the enemy and could not stop the British juggernaut as it rolled into the Transvaal. Johannesburg fell on May 30, and Pretoria followed on June 5. By the end of the summer, the British had cleared the last of the Boer resistance from the railway line running from Pretoria to the border of Portuguese East Africa. In the months that followed, the British turned to extreme measures in an effort to break Boer resistance. They built blockhouses to protect railways along which they moved troops and supplies, constructed internment camps, and embarked on a scorched-earth policy in which they routinely put Boer farms to the torch. In the internment camps, Boer women and children died by the thousands of hunger and disease.

Desperate to thwart the systematic destruction of Boer life in the Orange Free State, De Wet invaded Cape Colony in November with 1,500 men, forcing Roberts to detach a substantial number of troops to chase him off. The wily guerrilla leader invaded Cape Colony for a second time in February 1901. To deal with the 3,000-strong Boer force, the British detached another 14,000 troops to pursue them. It was a high-stakes game of cat and mouse.

As the war drew to a close in 1902, De Wet initially refused to go along with the majority of Boers who favored peace. He finally relented, but like a wolf in captivity, he chafed under the imposed peace. When World War I broke out in 1914, De Wet led an uprising in the Free State when South African leaders proposed to enter the war on the side of Great Britain and invade German South West Africa. In an ironic twist, De Wet’s former comrade, Louis Botha, led the forces that crushed the rebels and took De Wet into custody. De Wet was sentenced to six years in prison, but was released after a year with the promise that he would not have any further involvement in politics. It was an ironic end to an illustrious, if unorthodox, military career.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments