By Gregory Peduto

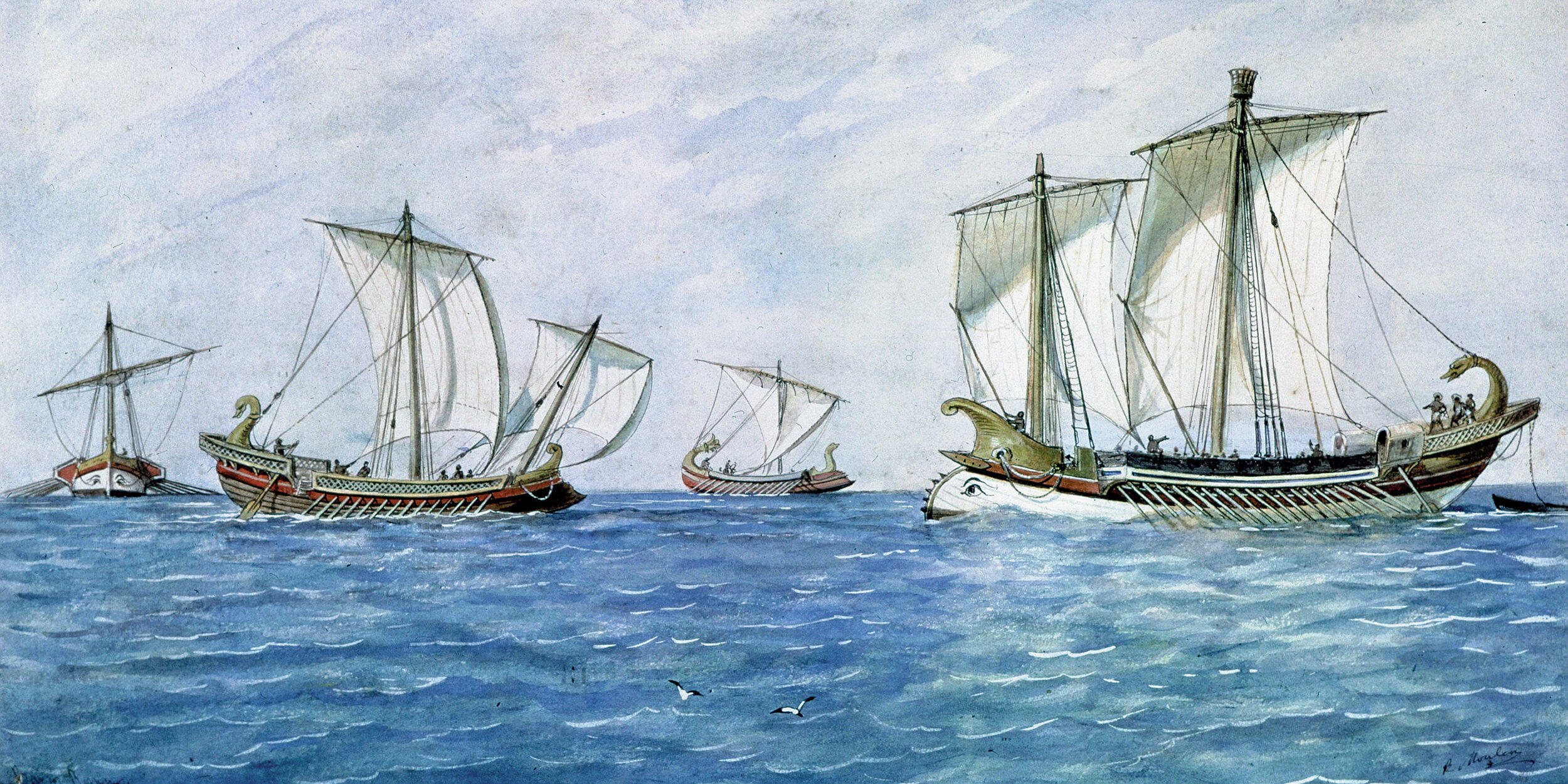

Wind billowed and waves crashed onto the deck of the massive 120-gun French flagship L’Ocean. From a window in his quarters, Captain General Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc studied the vast flotilla as it plowed through the lapping foam of the Atlantic. Comprising 32 lumbering ships of the line and 22 fragile frigates, the armada was the largest naval expedition in French history.

Within the holds of the vessels, more than 20,000 soldiers of Napoleon Bonaparte’s revolutionary Army of the Rhine obsessively oiled their weapons, scrubbing away all traces of saltwater corrosion. Hardened veterans of the emperor’s campaigns in Italy and Egypt, the soldiers were as diverse as the languages they spoke. Some of the troopers hailed from France, while others came from Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, or Germany. Their primary mission was to secure Louisiana for an eventual invasion of the United States. On the way, Napoleon had tasked the army with the deceptively simple objective of ending a slave revolt on the island of Saint Domingue (modern-day Haiti).

Haiti Readies for War

Leclerc knew the armada was nearing the rebellious island when the frigid waters of the Atlantic gave way to the clear blue-turquoise of the Caribbean. On January 29, 1802, the squadron anchored at the rendezvous point of Samana Bay, on the eastern shore of Haiti, and launched a massive amphibious campaign to restore slavery on the trouble-ridden island.

From the shoreline, the islanders watched in awe as the tall masts of the fleet blotted out the horizon. Wonder soon gave way to panic when the ex-slaves spotted French battle flags fluttering in the wind. News of the invasion spread rapidly across the tropical atoll’s villages. Everywhere the freed slaves cried ominously: “The French have returned!”

Hearing the cries, a mounted force galloped at breakneck speed over secret jungle roads and under hanging tropical vines. The barefoot horsemen wore a hodgepodge of bloodstained French shakos and British redcoats, grisly trophies of earlier failed European invasions. Some of the riders looked like a raiding party of black buccaneers, replete with jangling earrings and machetes thrust through their belts.

At the head of the ragtag detachment rode a gaunt African with three jagged scars running across his face. Wounded 17 times in battle, the leader bucked in his saddle, wincing in pain. The French called him the Black Spartacus—for good reason. In little more than 11 years, Toussaint L’Ouverture had risen from enslaved coachman to commander of the entire island. He could read and write both Latin and French. When it came to the nuances of guerrilla warfare, Toussaint rivaled anyone in military history.

The Slave Revolts That Defied Empires

In Haiti, insurrection served as the national pastime. Since the island’s first colonization, the fires of revolution had burned like a volcano. The slaves fought because they had no other options. Faced with daily whippings, brandings, and torture, nearly 40,000 Africans perished in Haiti each year. The brutal French plantation system only fanned the flames of insurrection. On the island, it was more economical to work a slave to death and purchase a new one than to take care of the existing workers. Baron de Wimpffen, a German visitor, commented on the brutal situation: “The cracking of whips, the smothered cries, and the indistinct groans of the Negroes, who never see the day break but to curse it.”

To make up for the murderous mortality rate, French farmers imported 30,000 to 100,000 slaves annually, but the massive introduction of Africans tipped the balance of power. The white population stood at a minuscule 24,000, in comparison to over 400,000 blacks. Impossible to control completely, thousands of escaped Africans took to the hills, setting up revolutionary bands known as maroons.

To make matters worse, the French faced another menace that danced to the reverberating beat of drums. The sounds announced the birth of voodoo, a bizarre new faith that mixed animistic West African religions with Catholicism and ritual possession. Thousands of nightly torch-lit vigils held in steamy swamps and deep ravines personified the resistance and unified the slaves in a common voice.

The first sophisticated revolt followed the growth of the religion in 1758 when a voodoo priest named François Mackandal hatched a failed plot to poison Frenchmen. Thirty-three years and three rebellions later, the slogans of the French Revolution reached the island’s shores, but the brutalized slaves understandably wondered where their liberty, equality, and fraternity were. In 1791, the African captives answered the question with an uprising led by a voodoo mystic named Boukman Dutty.

Toussaint earned his epaulets in Boukman’s army, and together the men burned the island to cinders. With bricks and iron cudgels, the rebels pushed the colonial forces of King Louis XVI into the sea. At the end of the revolt, Boukman was dead and Toussaint found himself in command of Haiti. The French abolished slavery to appease the insurgents, but the attempt backfired. The island’s plantation owners fumed at the decision and begged the British crown to intervene.

A 12,000-man British expeditionary force charged into the power vacuum, intent on pillaging Haiti’s legendary riches. With the swamp-bred aid of yellow fever, the Black Spartacus slaughtered the invading redcoats. Next came the Spanish, marching across the jungles from their half of the island, but Toussaint obliterated the invaders and captured their colony for good measure. It was becoming a habit with the battle-scarred leader.

Haiti: Napoleon’s Consolation Prize

Needing money—and quickly—the first consul of France undertook the risk of reinvading Haiti. British forces had routed Napoleon’s army on the sun-scorched Egyptian sands. Without the aid of colonies, Napoleon could not amass the funds necessary to finance a European conquest. For this reason, the French looked westward to the lost territory as a springboard for world domination.

Known as the Pearl of the Antilles, the island’s economy once had contributed a third of France’s foreign trade. Home to 655 sugar plantations, 1,962 coffee farms, and 398 cotton estates, the island previously sent 300,000,000 livres home to the mother country each year. In addition to the wealth, Napoleon had another reason for wanting to reassert control over Haiti. His wife Josephine inherited a massive plantation on Saint Domingue. She desperately wanted to reclaim the parcel of land, and her constant lobbying for an invasion drove the French leader to act. Napoleon later observed, “I believe that Josephine had some influence on that expedition, not directly, but a woman who sleeps with her husband always exerts some influence over him.”

Another factor was the destruction of the Corsican adventurer’s army in Egypt. That defeat forced the emperor to abandon his plans for eastern provinces. As part of the preliminary Treaty of Amines in 1801, the British offered Napoleon a consolation prize. The English invited him to retake Haiti to quell the slave rebellion and prevent the spread of such uprisings throughout the Caribbean.

Napoleon launched into the task of reconquest with his typical vigor, but the plot made little sense. Toussaint still considered himself a French subject. The rebels had never even declared independence. They simply desired abolition of slavery. If Napoleon had enlisted Toussaint’s aid, he might have conquered the entire Caribbean. Instead, he remained bent on war.

A Blond Napoleon on Campaign

Napoleon appointed his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, to head the campaign. Known derisively as the Blond Napoleon, Leclerc not only looked like the first consul, but also mimicked his mannerisms and style of dress. Even shorter in stature than Bonaparte, Leclerc proved one of the emperor’s most sycophantic followers. For good measure, he married Napoleon’s sister Pauline.

Napoleon needed a man well versed in the rigors of tropical warfare. For this position he chose Donatien Rochambeau, the son of the general who had fought alongside George Washington at Yorktown. An old hand in Caribbean insurrections, Rochambeau had battled rebellions on Martinique and Guadeloupe. To this leadership team, Napoleon assigned 20,000 men from the battle-hardened Army of the Rhine.

Drawn from Italian, German, and Swiss brigades, the men had fought for the ideals of the French Revolution with unflinching dedication. All told, the army contained five generals of division, nine generals of brigade, and 14 adjutants. The sheer size of the force presented a massive conundrum for the commander of the fleet, Admiral Villaret Joyeuse. There were not enough ships to transport the army. To make room, the admiral unloaded cannons in French ports and reduced his vessels to skeleton crews in order to cram more soldiers aboard. By then it was clear to everyone involved that Napoleon was displaying none of the tactical genius for which he was known.

His poor choices served to foreshadow his future defeat at the hands of the Russian winter. Sent in woolen metropolitan uniforms unsuited for the tropical heat, Leclerc’s men battled not only the slaves but also heatstroke. The regent also ignored the importance of re-supply in a tropical war. Napoleon decreed that the army must forage European-style to eat, an impossible task in a jungle war.

To match the problems of supply, the French dictator provided extremely vague invasion plans. To conquer Haiti, Napoleon devised a three-stage strategy of occupation. In the first stage, Leclerc would offer the black leaders false promises in order to allow the army to land peacefully and occupy strategic locations. Next, the army would round up the three main African generals: Toussaint L’Ouverture, Henri Christophe, and Jean Jacques Dessalines. With the black officers eliminated, the third stage called for the French army to re-enslave the population.

Toussaint Establishes his Defenses

By October 1801, the French fleet prepared to sail, but more indecision cost Leclerc’s army. The general’s wife insisted on traveling with her husband. It took her two months to assemble her wardrobe. If the Blond Napoleon had arrived earlier, he would have landed in the midst of a rebellion led by one of Toussaint’s generals. Instead, 4,000 miles across the Atlantic, Toussaint worked to consolidate his position.

Toussaint’s men stripped the ports of food and cached the supplies deep in the impenetrable Cahos Mountains. To defend these jungle stockpiles, the blacks constructed huge lumber and earthen fortresses throughout the bush. In addition to food, Toussaint’s army needed arms and ammunition, goods that came from the United States.

Toussaint’s men stripped the ports of food and cached the supplies deep in the impenetrable Cahos Mountains. To defend these jungle stockpiles, the blacks constructed huge lumber and earthen fortresses throughout the bush. In addition to food, Toussaint’s army needed arms and ammunition, goods that came from the United States.

In the 1700s, Americans downed 7.5 million gallons of rum each year. Molasses served as the lifeblood of Haiti’s economy, and New England depended on the sugary by-product to produce rum. Toussaint knew that resupply was impossible without molasses, and under his reign the substance flowed like water.

Napoleon believed erroneously that his invaders were facing a mass of unarmed rabble, but in reality, they were bristling with weapons. Boston merchants sold the Haitian military 30,000 muskets. Another 30,000 M1779 and M1777 .69-caliber French flintlocks and 60,000 Brown Bess muskets, left behind by the British when they withdrew from Saint Domingue, rounded out the freedom fighters’ armory.

What the slaves lacked in proper uniforms, they overcame with suicidal fanaticism. The long years of toiling in the cane fields had transformed Toussaint’s men into an army of virtual super-humans. They could live for months on a piece of salted cod and a tablespoon of rum a day. On these meager rations, the rebels often marched 60 miles a day. The French General Pamphile da Lacroix wrote admiringly, “No European army was ever better disciplined than Toussaint’s troops.”

The diehard army consisted of 20,650 men divided into three geographically based divisions. In the north, General Henri Christophe defended the country’s largest port, Le Cap François, with 4,800 men. A soldier since birth, Christophe had fought as a drummer boy in the American Revolution with the Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint Dominique. In stark comparison to Christophe was the brutal and despotic General Jean Jacques Dessalines, commander of the island’s southwest. Reared on a plantation, the tyrannical general faced a steady diet of whippings and torture throughout his life, which stoked the fires of racial hatred within his heart. With a division of 11,650 soldiers, Dessalines represented Toussaint’s most able—and ruthless—lieutenant.

In the Spanish sector of Haiti, Santo Domingo, Toussaint’s brother Paul headed a force of 4,200 men. Another 100,000 irregular soldiers stood in a constant state of readiness throughout the island. Armed with muskets, sabers, and machetes, these men formed a cadre of behind-the-lines fighters who disrupted enemy supply lines seemingly at will.

“No Other Resources Than Destruction and Fire”

On January 29, 1802, the French fleet pulled into Samana Bay. Watching from the undefended shoreline, Toussaint knew that there was only one way to defeat such a force. The rebel leader dispatched his fastest horsemen to the camps of Christophe, Dessalines, and Paul L’Ouverture with plans for the resistance. The message read: “Do not forget, while waiting for the rainy season which will rid us of our foes, that we have no other resource than destruction and fire. Tear up the roads with shot; throw corpses and horses into all the fountains, and burn and annihilate everything.” Only yellow fever could dismantle such an invasion, and Toussaint needed to delay the French until the coming of the rains brought the natural epidemic to bear on the enemy troops.

While Toussaint’s messengers galloped across the island, Leclerc’s armada split into three divisions to assail the island’s ports. In the north, Leclerc, Admiral Joyeuse, and a division of 7,000 soldiers moved on Le Cap François. Leclerc hoped to take Christophe’s 4,800-man division by surprise, but the wily African general sank every buoy in the harbor, preventing an amphibious attack.

Leclerc needed to envelop the rebels to stop them from disappearing into the jungles. If the insurgents escaped, the war might linger for years. To thwart Christophe’s retreat, Leclerc feigned a diplomatic parlay while Rochambeau and a naval squadron blasted nearby Fort Dauphin to gravel. Under the thunderous roar of the slaves’ cannons, Rochambeau and 4,000 men assaulted the narrow fortified peninsula of land in rowboats. Cannonballs flew through the air while the force rowed closer to the shore. Braving a storm of musket fire, Rochambeau’s troopers scaled the walls and slaughtered the defenders. With Fort Dauphin in French control, Rochambeau sealed off Christophe’s retreat to the southeast.

To provoke the general’s surrender, Leclerc dispatched a message to Christophe. He warned: “Unless you surrender, 15,000 men will be disembarking tomorrow. I hold you responsible for whatever might take place.” Christophe fired back an unflinching response. “The French will march here only across piles of ashes and that the ground will burn under their feet,” he said. “Even on those cinders, I shall continue to fight.” The reply horrified the French general. If the slaves destroyed Haiti’s infrastructure, the island would be useless as a moneymaker. To stop the destruction, Leclerc moved on Le Cap François with a coordinated land and sea offensive.

Le Cap François Burns

On the morning of February 6, Admiral Joyeouse towed two massive ships of the line up to the harbor with cables. Black gunners defending Fort Picolet unleashed 23 shots, but two broadsides from the gigantic 100-gun vessels reduced the fort to a mound of smoldering rubble. Surrounded by the heavy fog of the ship’s gun smoke, 300 French marines sailed for the city on small skiffs while Leclerc and 5,000 soldiers closed the noose around Christophe’s neck.

The French forces landed at L’Acul, southwest of the city. Using a mountain as a screen, the French marched behind Le Cap François to envelop the defenders. When Christophe discovered the trap, he distributed kegs of gunpowder and lamp fuel and put the city to the torch. Before retreating to the hills, the slaves lit a fuse that led to the city’s powder magazine.

Into the fiery holocaust charged Leclerc’s bayonet-wielding grenadiers. A wild fracas erupted as the slaves charged out of the city and the French charged in. The slaves were cornered and Leclerc moved in for the kill. Then the magazine blew. Splinters and shrapnel cut great swathes through the French forces. The well-timed explosion allowed Christophe enough room to flee into the mountains, but at day’s end Leclerc controlled the ruins of Haiti’s once-greatest city.

“Let Us Kill Without Noise”

While Leclerc and Rochambeau pacified the north, General Jean Boudet, Rear Admiral Louis-Rene Latouche Treville, and a division of 3,500 men sailed into the island’s western bay to conquer Port-au-Prince. To capture the city, Treville armed a flotilla of log rafts with small cannons. Boudet and his division then rowed the improvised dreadnoughts into the harbor.

From Fort Bizoton, General Jean Age, a white Frenchman fighting on behalf of the slaves, watched the force sailing toward the town. Spurred on by patriotism, Age refused to open fire. Emboldened by the lack of resistance Boudet ordered, “Let us kill without noise,” and the rafts landed on the outskirts of town.

Some rebels threw down their arms, while others opened fire. Age’s second-in-command, Louis Darue Lamartiniere, broke the stalemate by shooting an artillery officer who refused to open the powder magazine. Lamartiniere and a band of followers seized a quantity of artillery ammunition and sprinted to the city walls. His men loaded the guns and unloaded a storm of grapeshot at Boudet’s soldiers. Hearing the resistance, Admiral Treville brought his frigates into play. His naval guns silenced the city’s cannons, and allowed Boudet to force the gates. The French quickly captured the city intact and unburned, but once again the slaves escaped.

From the city of St. Marc, Jean Jacques Dessalines bitterly denounced Age’s treachery. He formed a raiding party of 6,000 men and raced to the city of Leogane, burning everything on the way. After he occupied Leogane, Dessalines murdered its white inhabitants and burned the city. Boudet sent a detachment of 1,000 light infantry to check Dessalines’s pillaging, but the seasoned guerrilla fighter avoided all open engagements. His rapid maneuvers soon had the French detachment chasing the guerrillas in futile circles.

While the fighting raged, Leclerc received letters detailing the slave’s crumbling resistance. Toussaint’s brother Paul surrendered the eastern half of the island without firing a shot. The Creole south under General Jean-François Laplume not only capitulated to the onslaught but also joined the French. Only the defense of the northern city of Port-de-Paix, led by the black General Jacques Maurepas and his 9th Regiment, continued to buoy Toussaint’s hopes.

The last vestige of a French colonial demi-brigade, the 9th Regiment represented the rebels’ most professional fighting force. On the morning of February 10, the regiment met General Jean Joseph Humbert’s 1,500 soldiers of the line at the city gates. Both sides formed European-style ranks and exchanged musket volleys. The slaves pounded Humbert’s men with shots while irregulars set fire to the city, burning it to ash. With the town destroyed, Maurepas withdrew, leaving behind 400 French corpses.

“This is a War of Arabs”

In little more than two weeks, Leclerc controlled every port on the island, but, in reality, the Blond Napoleon controlled nothing. It seemed like the jungle was swallowing regiments whole. Any time a French unit smaller than a division left the cities, it was met by an onslaught of hit-and-run attacks and poisoned wells. Leclerc voiced his fears in a letter to Napoleon: “This is a war of Arabs. We have barely passed before the blacks occupy the woods surrounding the roads and cut off our communications.” To end the resistance, Leclerc reasoned that he needed to capture the slaves’ supplies in the interior.

On February 18, Leclerc launched a massive offensive to converge simultaneously on Toussaint’s headquarters in Gonaives. From the northeast, Rochambeau moved his division from Fort Dauphin and advanced westward. General Jean Hardy occupied the center and marched south. General Edme Etienne Desfourneaux advanced south from the northwest. From the south, Boudet attacked northward from Port-au-Prince. The Black Spartacus was trapped between an onslaught of 12,000 French muskets and the sea.

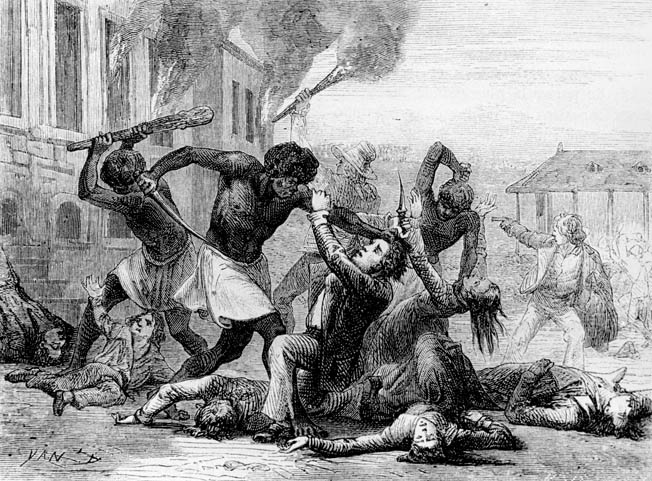

Natives revolting against the colonial French under General Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc in Saint Domingue (now Haiti) in 1802. Wood engraving, c1802.

The bloodthirsty Rochambeau exceeded all expectations and camped seven miles away from Toussaint’s headquarters. The Frenchman hoped to prevent the rebels’ getaway into the Cahos Mountains. Toussaint needed to stop Rochambeau’s advance to preserve his escape route. With a force of 1,500 grenadiers, 60 dragoons, and 1,500 plantation workers, the rebel leader prepared an ambush on February 23, at a deep ravine known as Ravine-a-Couleuvres.

For 12 hours, the slaves waited, muskets in hand, for the invaders to arrive. The tropical sun pounded down on the insurgents while insects chewed at their skin, but the fighters sat unperturbed. At dawn, Rochambeau’s division of 5,000 soldiers blundered straight into their trap.

Black sharpshooters rained down volleys of musket balls from camouflaged hiding places atop the cliffs. When a trumpet sounded, a wave of ax-wielding plantation workers slammed into the division. Bitter hand-to-hand fighting broke out everywhere, and by noon the ravine grew slick with gore. By 1 pm, the slaves had driven the French into a small stream and prepared to annihilate the invaders, but Rochambeau rallied his men. The French general hurled his hat into the black ranks and screamed, “My comrades, you will not leave your general’s hat behind!” The tactic transformed the 5th French Light Infantry Regiment into a pack of frothing berserkers. A howling charge pierced the rebel lines, and the 5th recovered their general’s hat and saved the division, but Toussaint had already done the impossible, preserving the escape route to the Cahos.

Toussaint occupied his last fortified bastion in the mountains, the impressive citadel of Crete-a-Pierrot. Dessalines arrived at the castle days later, and the two prepared for a lengthy siege. The British-constructed, 300-foot-high stone citadel served as the slaves’ most imposing stronghold. Bristling with English .24-caliber cannons and a dry moat surrounding the castle, Crete-a-Pierrot was the key to the rebel position. Taking it would destroy the slaves’ supplies and end the war.

On March 11, 1802, a long line of European soldiers hacked a trail through the lush vegetation in search of the castle. From the north and south, Rochambeau, Boudet, General of Brigade Jean Debelle, and General of Brigade Pamphile da Lacroix converged on the outpost with 12,000 soldiers. Toussaint left Dessalines and Lamartiniere, the hero of Port-au-Prince, in command of the vital station and hastened northward to recruit more soldiers. With Toussaint gone, only 1,200 slaves remained to fight the entire French army. To open a hole for Toussaint’s escape, Dessalines and a cadre of men charged the invaders. Toussaint got away, and Rochambeau’s division broke off the engagement to give chase, leaving Boudet to confront the fortress alone.

Dessalines feigned retreat and enticed the cocky Europeans to charge straight into the fort’s camouflaged artillery. When the pursuing Frenchmen wandered into range, Dessalines and his men dove into the dry moat. Flashes of fire and smoke erupted over the slaves’ heads, mowing down 400 French soldiers. Boudet withdrew his troops to await his mortars, but the dense underbrush made the transportation of artillery a nightmare. To speed up the attack, the commander elected to take the fort the next day with an onslaught of flesh.

That night Dessalines rallied his men around the ramparts and delivered a rabble-rousing speech, promising: “We shall be attacked this morning. All those who wish to become slaves of the French may leave the fort.” Not a single warrior left the castle, and the ferocious general grabbed a blazing torch and held it perilously close to a powder keg, crying, “I shall blow you all to glory if you let the Frenchmen into this fort!” No one could sleep for fear of being surprised by Boudet’s blitz.

“A Remarkable Feat of Arms”

At dawn, the French general drew his saber and led a wild charge at the rebel redoubt, but the attack proved useless. A storm of gunfire cut down 800 French soldiers; a stray shot clipped Boudet’s heel and took him out of action. After repulsing the attack, Dessalines left Lamartiniere in command of the bastion and slipped away through the jungle to recruit more men.

While awaiting the heavy guns, the French attempted to mine the walls of the redoubt, but the intense tropical humidity made the work impossible. Rochambeau then led wave after wave of French soldiers to their doom. Finally, the mortars arrived and the siege guns bombarded the fort for eight days. The slaves fought on without a drop of water. By March 24, Lamartiniere and 500 remaining men decided to fight their way out of the stone coffin.

At 9 pm the fleeing slaves fell upon Rochambeau’s sleeping division. The surprise assault enabled Lamartiniere and his fighters to break through the lines and disappear into the undergrowth beyond. In his memoirs, Lacroix called the move “a remarkable feat of arms.” The next morning, Rochambeau occupied the empty fortress and counted his dead. The fruitless victory had cost the invaders 2,000 soldiers, but the French tragedy had just begun.

Great arcs of lightning cut across the humid night sky. Thunder roared and rain fell in sheets. The moisture collected in stagnant pools in every field, pothole, and crevice. From these pools came swarms of mosquitoes that dined upon the exhausted French troops. The rainy season had arrived, and with it the dreaded yellow fever.

The French soldiers keeled over in droves, stricken with a plague of biblical proportions. Fever cooked victims’ brains until they heaved forth black vomit, their faces turned a ghoulish yellow, and they died. Leclerc wrote Napoleon to tell him of the disaster. “I have already more than 1,200 men in the hospital,” he reported. “Calculate on a considerable waste of life in this country. Send reinforcements.” At the current death rate, Leclerc reasoned that his army would be a pile of corpses by September. The emperor shuttled more thousands of his men into the Caribbean hell. He even dispatched 8,000 soldiers from the famed Polish Legion, but the reinforcements only fueled the spread of disease. The war in Haiti was unwinnable.

The Struggle for Power in Haiti

To forestall his inevitable defeat, Leclerc implemented a bold divide-and-conquer ploy, opening negotiations with Christophe and Dessalines in the hope of enticing the black generals to betray Toussaint. In return for that betrayal, Leclerc offered the men commissions as generals in the French Army.

By joining the French, Dessalines and Christophe planned to capture the island for themselves. It was clear that the French were finished—only Toussaint prevented the two from seizing total control. If the pair disposed of the Black Spartacus, they had only each other to vie with for hegemony.

Leclerc, Christophe, and Dessalines convinced Toussaint to surrender, promising not to reinstate slavery. Toussaint surrendered on May 1, and Christophe and Dessalines pushed for his immediate deportation. On June 7, French soldiers seized Touissant, locked him in irons, and threw him aboard a ship bound for Europe. Haiti’s Black Spartacus died one year later in a frigid dungeon on the Swiss border.

The deception plunged the island into an uproar. Black forces led by voodoo mystics split into tribal affiliations and battled the French and other blacks. Meanwhile, Christophe and Dessalines jockeyed for a total takeover. The two leaders set up the remaining Frenchmen for ambushes while also supplying the rebels and killing any black leaders who challenged their authority.

A War of Extermination

On April 27, 1803, Napoleon officially reinstated slavery in Haiti, and every man, woman, and child arose in armed resistance. Leclerc responded by waging a war of extermination, gassing, drowning and slaughtering whole families to quell the revolt, but the resistance continued. On May 18, Great Britain declared war on France. The famed Jamaica Naval Squadron descended on the island and cut off all supplies. By now, Napoleon had forgotten all about the distant campaign and ignored Leclerc’s pleas for help.

Without fresh food, the French ranks were ravaged by fever. By July, more than 10,000 French soldiers had succumbed to the black vomit at a rate of 160 men a day. General Hardy dropped dead, along with 65 percent of Leclerc’s general staff. On November 2, Leclerc himself fell victim to the outbreak and died. Napoleon promoted Rochambeau to general in chief of the expedition, but he could do little to reverse the catastrophic losses.

To make up for the casualties, Rochambeau imported 600 slave-hunting dogs from Cuba. As with everything in the utterly vicious war, the dogs proved bloodthirsty, savage, and unpredictable. In their first battle, the animals devoured a French drummer boy. The dogs did not stem the tide, and Dessalines and Christophe rebelled. Armed with English guns, uniforms, and ammunition, they pushed Rochambeau to the breaking point, forcing him to withdraw the remains of his shattered army to Le Cap François on June 26, 1803.

Rochambeau strengthened the city’s defenses by constructing a chain of blockhouses defended by 72 cannons and 2,000 soldiers. In the middle of the chain was Fort Vertieres. Defended by the 11th demi-brigade, the fort contained only 300 men. This tiny force was about to battle 18,000 of Dessalines’s troops arrayed in 12 brigades.

The slave army descended upon the blockhouses in human-wave assaults. The French poured fire into the blacks, mowing down some 1,200 rebels, but one by one the redoubts fell. The rebels turned the blockhouses’ cannons on Fort Vertieres. The salvo ignited the castle’s powder magazine and blew it to smithereens. With Vertieres destroyed, the rampaging horde headed for the city.

The High Cost of Freedom

On October 8, Rochambeau loaded his surviving troops onto three frigates and pulled out of Le Cap François for the last time. Only 3,900 solders remained from the once-grand expedition. The losses amounted to one dead general in chief, five deceased generals of division, 14 slain generals of brigade, and 54,000 lost solders. The slaves paid an even higher price. Nearly 80,000 Haitians perished in the conflict, but their reward was freedom—they had defeated one of Europe’s finest armies in the first successful slave revolt in history.

Napoleon considered the failed expedition one of his worst losses. He later admitted in exile: “My greatest mistake was to try and subdue Haiti by force of arms. I should have let Toussaint L’Ouverture rule it.” Bonaparte’s dreams of an American empire were dashed as well, and on April 30, 1803, the diminutive dictator sold Louisiana to the United States. In a way, Toussaint had helped save America, as well as Haiti, from the imperial ambitions of a ravenous Napoleon.

Considering the events since and until today, Haitian people would have been better off remaining with France.