By David A. Norris

Smoke swirled amid the thunderous noise that roared from powerful Dahlgren guns and Brooke rifles. Thousands of spectators along the shore watched the two most dangerous warships in the world at each other at point-blank range. Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones hoped that his Virginia would overcome the Monitor and clear the U.S. Navy from Hampton Roads, Virginia.

Jones was startled to see a party of his gunners standing idle. Confronting Lieutenant John R. Eggleston, Jones asked, “Why are you not firing, Mr. Eggleston?”

“Why, our powder is very precious, and after two hours’ incessant firing I find that I can do her about as much damage by snapping my thumb at her every two minutes and a half,” replied the lieutenant.

Eggleston was right. Alone, either ship could have cut a swath through any of the world’s navies. Matched against each other, heavy explosive rounds fired by one combatant simply bounced off the sides of the other. Shell after shell burst uselessly in the air. Others splashed into the water, throwing nothing more harmful than a little salt spray through the gun ports.

On March 9, 1862, the Union and Confederate navies fought the first naval action in history between two ironclad vessels, the Monitor and the Virginia. Both combatants at the Battle of Hampton Roads represented remarkable leaps in naval technology. Less than one year before the battle, no one could have possibly dreamed that these two ships would meet and alter the course of history. The Virginia had been a completely different ship in a different navy, and nothing then existed of the Monitor other than a batch of design drawings and a pasteboard model.

Capturing the Merrimack

Secessionist gunners opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861. One day after the fort surrendered, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to confront the rebellion, and secessionists moved to seize federal military installations in other Southern states.

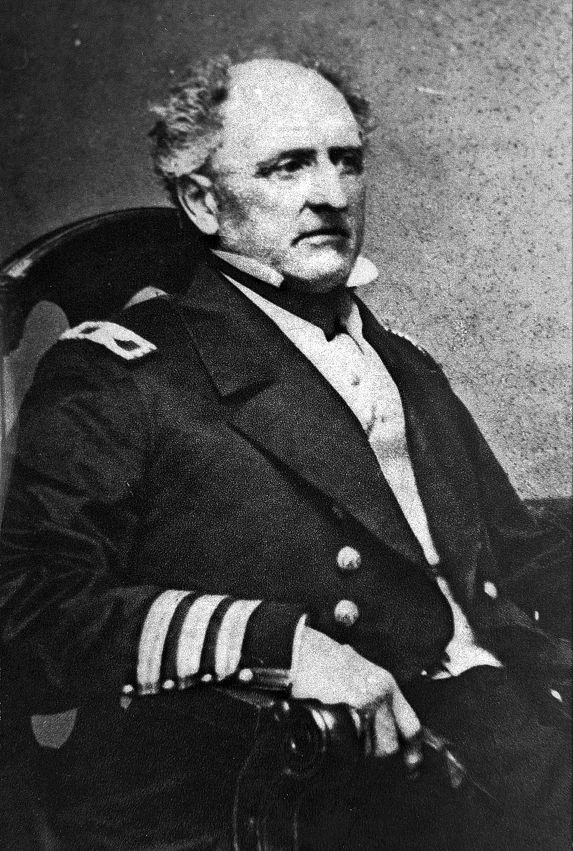

Perhaps the greatest potential prize for the secessionists was the U.S. Navy’s Gosport Shipyard, on the western shore of the Elizabeth River in Virginia. Captain Charles Stewart McCauley, a veteran of the War of 1812, commanded the Gosport Shipyard. In early 1861, there were a dozen warships in varying states of readiness or neglect at the yard. U.S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles worried that Virginian secessionists might capture the shipyard. Among the ships at Gosport was the steam frigate Merrimack, which was scheduled to have her engines replaced. On April 11, Welles ordered McCauley to get the Merrimack ready for sea so a crew could remove her to safety in Philadelphia.

McCauley, though, accomplished nothing. Secessionist sympathizers persuaded him that any action on his part would provoke an attack by Virginian troops. Welles sent Captain Hiram Paulding to replace McCauley and prevent the capture of the vessels at the shipyard.

When Paulding arrived on the evening of April 20, it was too late. Fearing that a secessionist attack was imminent, McCauley ordered his men to scuttle the warships and set the workshops on fire. Paulding retrieved only two ships, the steam sloop of war Pawnee and the sailing frigate Cumberland.

Virginia troops moved into the Gosport Shipyard on April 21. A vast bounty of war materials fell into Rebel hands. Approximately 1,000 cannons and 2,000 barrels of gunpowder were taken unharmed, not to mention thousands of rounds of shot and shell. Union sailors had scuttled nine naval vessels, ranging from outmoded ships of the line to the modern steam frigate Merrimack.

Although the Merrimack was burned to the waterline and then sunk, her draft of 24 feet, 3 inches meant that her engines and a great deal of her hull escaped damage. Enough remained for a rebuilding project.

An Ambitious Rebuilding Project

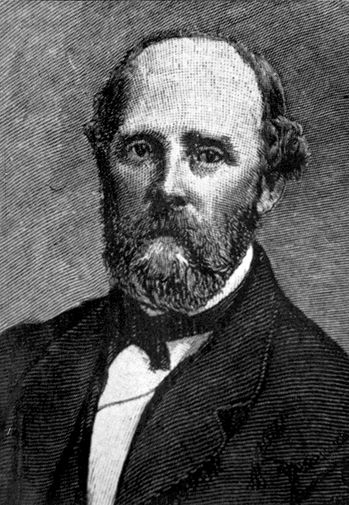

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory saw ironclads as a way for his navy to counter the Union’s advantages in naval strength and industrial potential. Time was of the essence, and the Merrimack’s hull and its engines would give the South a head start in building a new ironclad at the captured navy yard.

For the new ship’s design and construction, Mallory consulted with Navy Lieutenants John Mercer Brooke and John L. Porter. Mallory chose a plan proposed by Brooke. Porter supervised the overall construction of the vessel, and Brooke saw to the armor plating and the ship’s guns.

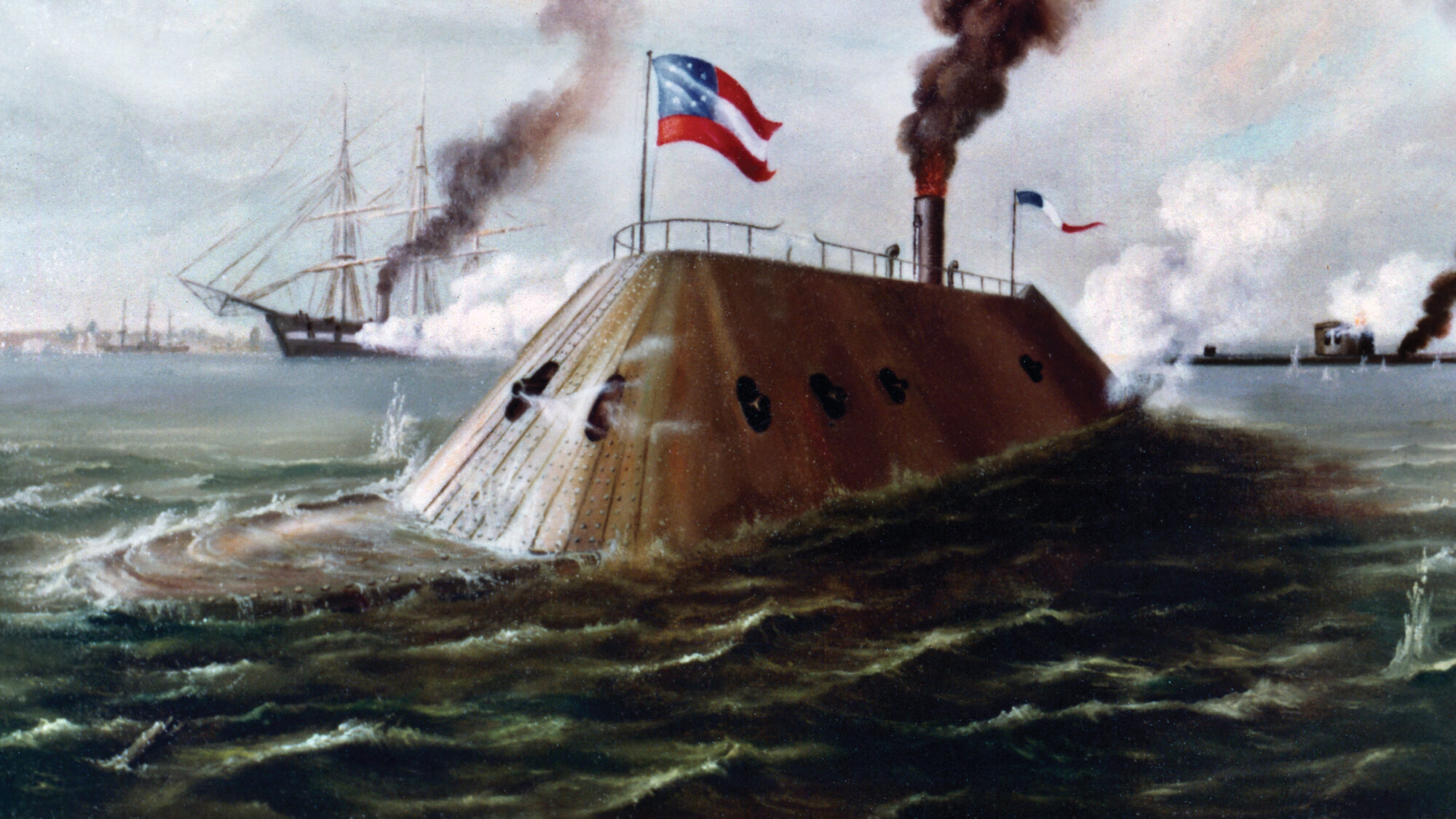

Workmen razed the Merrimack to the level of her old berth deck and built a new main deck. Atop the deck rose a 170-foot-long casemate. Little of the hull was exposed; ahead and astern of the fortress-like casemate, the main deck was intended to ride about level with the waterline and would be awash when underway. Two feet of pine and oak planking covered by two two-inch-thick layers of iron protected the casemate. Angled at 35 degrees, the steep pitch of the casemate walls helped deflect enemy shot.

Aboard the Merrimack were 10 guns. Two 7-inch Brooke rifles peered from the bow and the stern of the casemate. Two 6.4-inch Brooke rifles and six 9-inch smoothbore Dahlgrens served as the broadside guns. Another weapon harked back to ancient times: a 1,500-pound, wedge-shaped cast iron ram. Lieutenant John R. Eccleston recalled that the ram “was about two feet under water, and projected about two feet from the stem. It was not well fastened.”

Although officially renamed the Virginia, the ironclad was still called the Merrimac (with the final “k” dropped) by most Northerners and many Southerners.

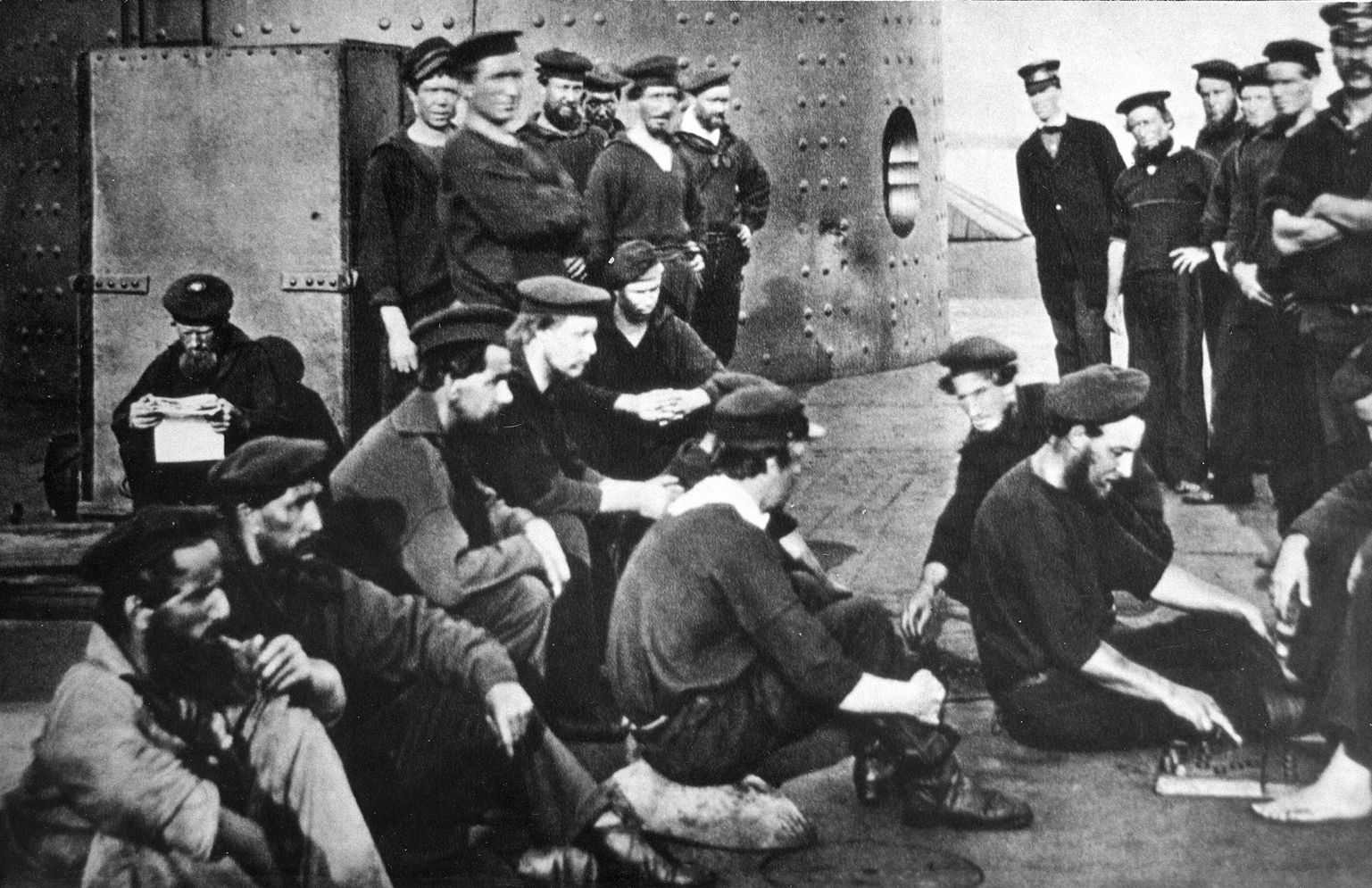

In action, the Virginia would have 320 officers and crew. Most officers were veterans of the antebellum U.S. Navy. Jones would become the Virginia’s executive officer. Stepping into command of the James River defenses and the Virginia was Captain Franklin Buchanan, the first superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy. Experienced officers were easier to come by than skilled sailors. Although a sizable portion of the old navy’s officers resigned to join the Confederacy, few enlisted men followed them. In desperation, Lieutenant John Taylor Wood hunted for volunteers from the army camps around Norfolk. About 80 soldiers were obtained for the crew, including a detachment of about 30 men from the Norfolk United Artillery under Captain Thomas Kevill.

The green recruits had about two weeks of drill with naval guns aboard the Confederate States. Once the frigate United States, the 1790s-era ship was so worn out that the Federals did not bother to scuttle her when they fled from the Gosport Shipyard. Desperate for any type of vessel, the Rebels used her as a receiving ship. There was no time to train with the larger guns aboard the Virginia, and the first time the crew fired them, they would be in action.

The “Ericsson Battery”

Word of the mysterious and dangerous new Confederate project under construction at the Gosport Shipyard reached the North. As the Rebels rushed to complete their “iron battery,” the Union scrambled to counter this new threat.

A man with a potential answer to the Union’s emergency was John Ericsson. The Swedish-born inventor had a long record of innovations. He was one of two inventors who independently introduced the screw propeller in 1836. Ericsson also designed the Princeton, the first screw propeller ship in the U.S. Navy.

The U.S. Navy issued a call for new ironclad vessel designs, with a deadline of August 15, 1861. Businessman Cornelius Bushnell, who pushed a design of his own, showed Ericsson his plans. While approving of Bushnell’s proposed vessel (which became the Galena), Ericsson shared a much more visionary plan of his own. Bushnell was so impressed with Ericsson’s ideas that he used his considerable influence to help the Swedish inventor get a contract to build what became the Monitor.

On October 25, 1861, the keel was laid at the Continental Iron Works at Green Point, New York. Parts of the vessel, including the turret and the engines, were built elsewhere and brought to Green Point for final assembly.

For months called “Ericsson Battery,” the craft was an all-iron vessel with a main deck that rose scarcely 18 inches above the waterline, leaving little freeboard for enemy gunners to hit. Besides collapsible smokestacks, little interrupted the flat expanse of the deck other than an armored gun turret and a small pilot house. With a cylindrical turret atop the almost featureless deck, it is little wonder that the ship was called “a cheese box on a raft.”

Ericsson’s ironclad was 172 feet long and had a beam of 41.5 feet. The broad flat deck overlapped far beyond the hull to protect the engines, rudder, and propeller. Inside the iron turret, which had an interior diameter of 20 feet, were two 11-inch Dahlgren guns. The turret rotated under the power of the ship’s engines. Forced-draft ventilators stoked the fires and refreshed the air in the engine room.

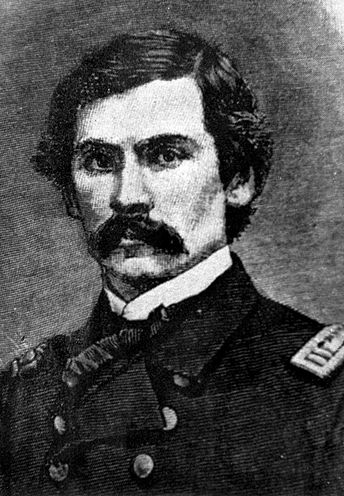

Lieutenant John L. Worden was chosen as captain of “Ericsson Battery” on January 16, 1862. Worden would command a much smaller crew than Buchanan. Executive officer Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene wrote that, including the captain, there were 58 men aboard when the ironclad first went into action. Worden wrote Gideon Welles about the gun turret: “17 men and 2 officers would be as many as could work there with advantage; a greater number would be in each other’s way and cause embarrassment.”

The Troublesome Iron Clads

Commissioned on February 25, 1862, Ericsson’s ship was given the name Monitor. When the peculiar-looking craft steamed into the East River two days later, it looked like Ericsson won the sprint to finish his iron vessel before the Rebels commissioned theirs. But the trip was cut short because the steering failed. Then, during an attempt to steam to the South, stormy weather in the Atlantic threatened to swamp the Monitor, and she again returned to port.

At Gosport, the South’s long-awaited ironclad was commissioned on February 17, 1862. She was 275 feet long and drew 22 feet when loaded. Artisans rushed to complete the final stages of construction. A lack of gunpowder kept the vessel out of action. Scraping up supplies of powder took several days, then there was a further wait while the gunpowder was measured out for cartridges.

Although reconditioned as much as possible, the Virginia’s second-hand engines were just barely adequate; they could manage just six knots. Turning the unwieldy vessel around took half an hour.

The North was desperate to get the Monitor to Hampton Roads before the Rebels’ ironclad could ravage the Union’s vulnerable wooden warships. On March 6, the Monitor left New York again. Far at sea by the next day, the iron vessel struggled to stay afloat. Water rolled over the deck, surging into the pilot house and knocking down the helmsman. There were a host of other problems as well. The most technologically advanced warship in the world was in peril of sinking before getting a chance to fire a single shot.

But the hands held to their work all night. By the next morning, the weather moderated and the exhausted crew headed for Hampton Roads. Whatever the outcome of the upcoming clash with the Rebels, it was clear that the Monitor would never be fit for long-term duty at sea.

“Swinging Lazily by their Anchors”

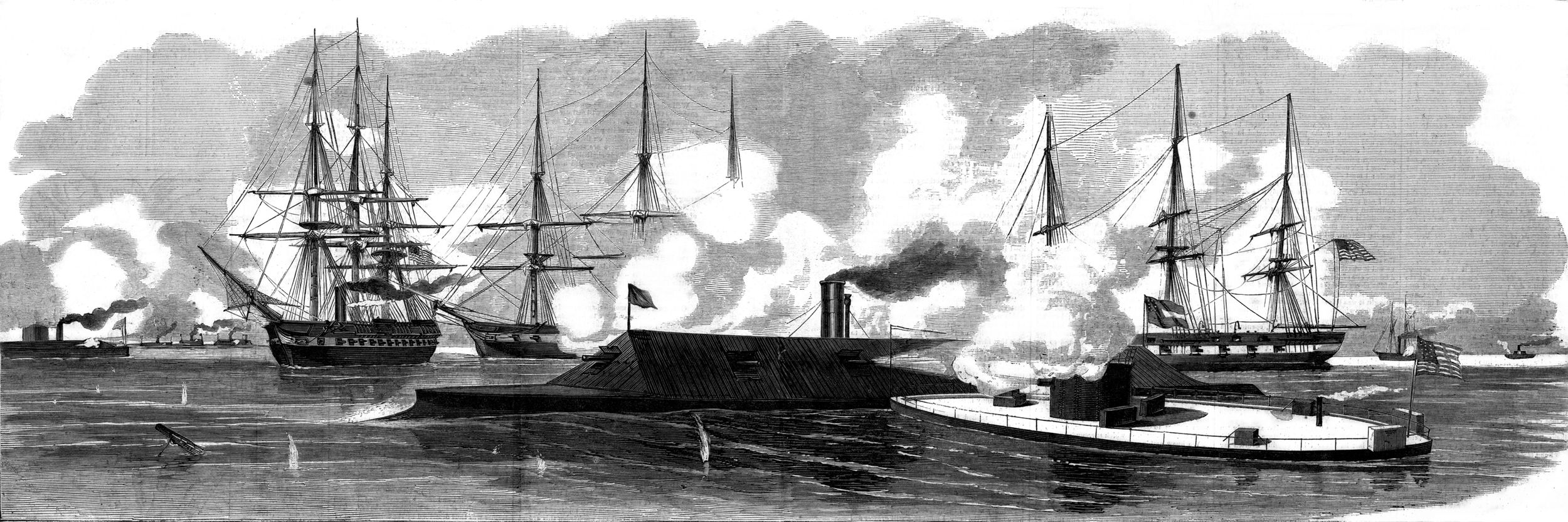

On March 8, with the Monitor still out in the Atlantic, the Virginia was ready for action. She left the Gosport yard and headed for Hampton Roads, a wide estuary where the James, Nansemond, and Elizabeth Rivers unite and empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Guarding the entrance by the Chesapeake stood Union-held Fortress Monroe and the Rip Raps, an artificial island occupied by the Union’s Fort Wool.

The main channel ran between the Confederate-held southern shore and the Union-occupied northern shore. A shallow called the Middle Shoal split the passage into the North Channel and the South Channel. Confederate land batteries kept the Union ships toward the northern fringes of the deep channel.

In Hampton Roads was a Union naval force headed by the screw frigates Roanoke and Minnesota and three sailing frigates, the Cumberland, Congress, and St. Lawrence. With them were numerous other craft, including a hospital boat, three colliers, five tugs, and a dozen small gunboats.

The Virginia steamed out of the Elizabeth River, keeping to a narrow channel between a projecting headland on the right and the shallow stretch of the Craney Island Flats to the left. In support of the Virginia were the gunboats Raleigh and Beaufort. At 1 pm, the Virginia cleared Sewall’s Point.

Later in the day, three vessels of the James River Squadron would join the Rebel force: the converted sidewheel passenger steamers Jamestown (officially named the Thomas Jefferson) and Patrick Henry and the tugboat Teaser. The Patrick Henry carried 10 guns, but the others had no more than one or two guns apiece.

Past Sewell’s Point, the ironclad made a slow turn to port. This turn brought her south of the Middle Shoal. The Confederates drew nearer to the sailing vessels Cumberland and Congress off Newport News Point. The day was calm, and Wood remembered the pair of Union frigates “swinging lazily by their anchors.” Their crews seemed to have no idea of the catastrophe that loomed. Wood saw “boats hanging in the lower booms, washed clothes in the rigging.” Upon seeing the Virginia, the idyllic mood aboard the sailing ships vanished and their crews rushed to their battle stations.

The Battle of Hampton Roads Begins

Aboard the five Union frigates were a total of 200 guns. Had they been able to maneuver together to concentrate their fire on the Virginia, the wooden frigates might have stood a chance of inflicting critical damage. But on that day there was so little wind that the sailing vessels relied on tugboats to move. The St. Lawrence was too far away to lend support. As for the steamers, the Roanoke’s main shaft had been awaiting repair for months. There was nothing the Roanoke could do except make a show of releasing angry clouds of steam. A shot from a Rebel battery at Sewall’s Point hit the Minnesota’s mainmast, and the steamer soon ran aground about a mile east of Newport News Point.

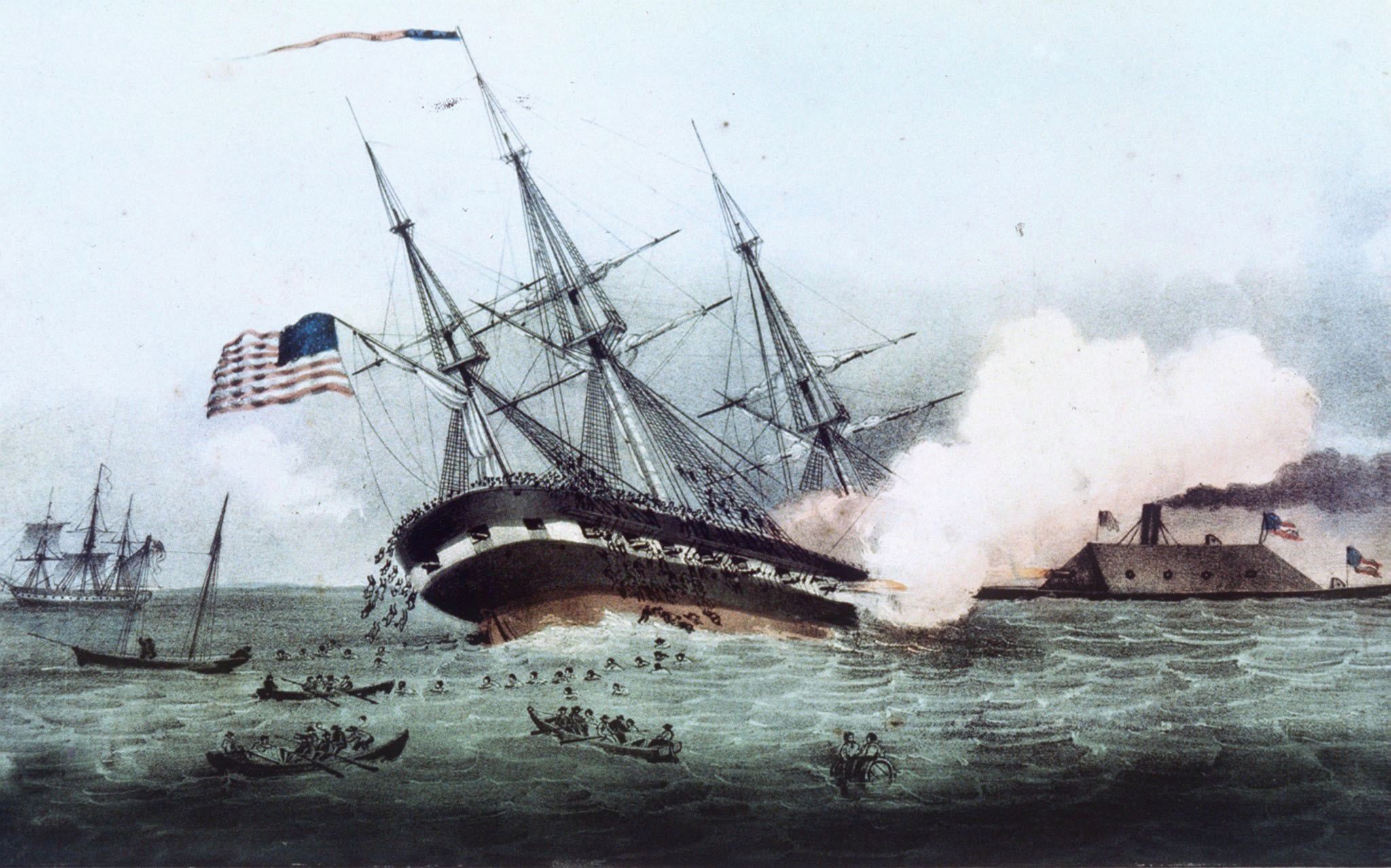

This chain of setbacks left the two sailing frigates to face the oncoming Virginia alone. Buchanan wrote that “the Virginia commenced the engagement” by firing her bow gun at the Congress. Two dozen 32-pounders aboard the Congress answered with a broadside. Close to 800 pounds of metal flew across the water. But any shots that hit their mark simply clanged against the Virginia’s armor and bounced off. The armor plating seemed invincible, but Chief Engineer H. Ashton Ramsey recalled the officers still continually warned the gunners, “Keep away from the side ports, don’t lean against the shield, look out for the sharpshooters.”

Passing the Congress, the Virginia built as much speed as possible and made straight for the Cumberland. Captain William Radford of the Cumberland was not aboard his ship. That morning, Radford was on the Roanoke, serving on a court of inquiry. Seeing his ship in peril, Radford went ashore, obtained a horse, and rushed toward Newport News. There was no time for Radford to reach his ship, and executive officer Lieutenant George U. Morris was in command as the Rebel ironclad neared.

Wood recalled that the Cumberland opened fire with her pivot guns, and then the Congress and the enemy shore batteries joined in. Aboard the Virginia, Lieutenant Charles Simms aimed the forward Brooke rifle. When Simms fired, the shot wiped out most of the Cumberland’s aft pivot gun crew.

Ramming the Cumberland

About 15 minutes after the firing began, the Virginia closed in on the Cumberland. Ramsey heard the orders communicated to the engine room. “Two gongs, the signal to stop, were quickly followed by three, the signal to reverse.” There was a brief interval while the ship sliced through the last few yards of open water. Then, the ironclad snapped through a futile barrier of spars set afloat to fend off nautical mines. Approaching at a right angle to the enemy vessel, the iron ram of the Virginia plowed deep into the Cumberland’s starboard bow, just ahead of the fore chains. Heavy hull timbers and planking gave way as if they were sticks.

Aboard the Virginia, Lieutenant Jones remembered that he felt little of the impact, but, “The noise of the crashing timbers was distinctly heard above the din of battle.” Down in the engine room, the impact felt heavier. Ramsey recalled it as a “crash, shaking us all off our feet.” The engines “labored,” and “we seemed to be bearing down with a weight on our prow,” he wrote. Indeed, the iron prow was locked inside the crushed hull timbers of the Cumberland. As the stricken ship settled into the water, she threatened to pull the Virginia under as well. Lieutenant William Harwar Parker of the Beaufort observed that the bow of the Confederate vessel “sunk several feet.” Reversing the engines, the Rebels managed to back away. Unknown to Buchanan and his officers, the ram broke off and stayed embedded in the doomed Cumberland.

A few shots from the Cumberland struck home. A Yankee shell exploded near a port by the forward 7-inch Brooke rifle, hitting several men with fragments. About half of Kevill’s detachment manned one of the broadside guns, a 9-inch Dahlgren. Two of the captain’s gunners were wounded by musket balls. Just after the crew loaded another round, a shot hit their Dahlgren, simultaneously firing the gun while knocking off its muzzle. Despite the damage, Kevill’s gunners kept on firing the gun for the rest of the battle.

Another Yankee shot struck one of the 6.4-inch Brooke rifles and broke off the tube at the trunnions. The crew kept on loading and firing this gun as well, even though each discharge set the wood around the gun port on fire.

Demonstrating the Iron Clad’s Devastating Advantage

For a bit of added protection against enemy shot, the armor of the Virginia bore a thick coating of pork grease. There was some hope that by making the iron plating slippery, the grease would help deflect enemy shot. Soon the odor of the pork grease blended with the sulfurous scorching smell of exploding gunpowder. To Midshipman H. Beverly Littlepage, it seemed that the Virginia was “frying from one end to the other.”

Far worse than the few random hits taken by the Virginia was the devastation brought down upon the Cumberland. As water poured in through the hole smashed open by the ram, more shot tore through the hull and over the deck. Morris’ gunners kept up their return fire, and other hands fought a losing battle to pump out the water pouring into their ship. By 3:30 pm, the forward magazine was flooded. For another five minutes, powder from the aft magazine fed the Cumberland’s 10-inch gun, the ship’s best chance of fighting off the Rebel attack.

About that time, Radford arrived at Newport News. Before he could order a boat, the Cumberland keeled sharply to port. Only minutes after the Virginia’s ram smashed into the wooden frigate, water washed over the main hatchway of the Cumberland. Emptying their guns in a final gesture of defiance, the crew abandoned ship.

Up until March 8, 1862, duels involving a pair of warships had often taken hours of maneuvering and firing. At Hampton Roads, it took perhaps one quarter of an hour to end the centuries-long age of the wooden warship. After a fleeting exchange of fire, the Cumberland was lost. One third of the crew was dead.

“Like Water on a Wash-Deck Morning”

Buchanan was now free to finish off the Congress. Reaching the enemy ship required the Virginia to steam up the James River for more than a mile while steering to port until the ship made a wide enough arc to turn around. Scraping and dragging in the mud in the bed of the channel, the keel slowed the ironclad and made the turn take even longer. All the while shore batteries exchanged fire with the Rebel vessels.

A shot punctured a boiler on the Patrick Henry, killing four of the crew. The steamer was towed out of range until repairs to the boiler enabled the ship to return to action. During this stage of the battle, Confederate fire blew up a steamer at a Union wharf, and the Rebel gunboats sank one schooner and took another as a prize.

When the crew of the Congress first saw the Virginia steam up the James, the Yankee tars cheered, believing that the ironclad was retreating. Relief quickly gave way to a dreadful reality. Already peppered with rounds from the emboldened enemy gunboats, officers on the Congress soon realized that the Virginia was coming for them. Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith, the ship’s captain, ordered the tug Zouave to come alongside and drag the frigate aground on a sandbar.

Carefully easing toward the shallows protecting the enemy vessel, Buchanan’s pilot managed to get within 150 yards of the stern of the Congress. The Virginia joined the gunboats in raking the stranded frigate. Smith could reply only with two stern guns. It was not long before one gun was dismounted and the other had its muzzle blown off. Grape and shot plowed through the Congress, hitting dozens of the crew. Among the officers aboard the ship was Paymaster Thomas McKean Buchanan, brother of the commander of the Virginia.

Blood ran down the tilted deck of the Congress, spilling over the scuppers “like water on a wash-deck morning” onto the Zouave, remembered Acting Master Henry Reaney. Broadsides from the Virginia raked the Congress, knocking over more of her guns. Aboard the Zouave, a Confederate shot smashed its figurehead, “which was a fixture atop our pilot house.” The broken statue hurtled through the air and wounded two of the Zouave’s gunners.

Firing on a White Flag

Lieutenant Smith was killed at about 4:20 pm. Fire broke out as incoming shells slaughtered more sailors. Amid the chaos, Smith was dead for 10 minutes before executive officer Lieutenant Austin Prendergast learned that he was in command of a defenseless and dying ship. Prendergast had no option but to surrender, but the Zouave managed to get away.

Buchanan sent the Beaufort to take possession of his prize, offload the prisoners, and burn the ship. Prendergast stepped onto the Beaufort with Captain William Smith; the latter officer, recently reassigned from command of the Congress, was still aboard and serving as a volunteer officer. Prendergast surrendered the ship, although Parker noted that the Union officer handed over an ordinary cutlass rather than his own sword.

Upon hearing Parker’s orders from Buchanan, Prendergast pleaded with Parker not to set the Congress afire, as 60 wounded men were still aboard. As they talked, wounded sailors were being transferred to the Beaufort. The gunboat Raleigh joined them, and Parker directed their officers to help removed the wounded Union crewmen.

Then, Union soldiers on shore opened fire on all three vessels. All the men standing on the deck of the Beaufort, other than Prendergast and Smith, were killed or wounded. Two officers were killed aboard the Raleigh, and some of the wounded Yankee sailors were shot by their own men. Parker was wounded in his left knee. He wrote, “Lieutenant Pendergrast now begged me to hoist the white flag, saying that all his wounded men would be killed. I called his attention to the fact that they were firing on the white flag which was flying at his mainmast.”

Buchanan’s temper flared at what he saw as a treacherous violation of the rules of war, and he ordered the heating of some 9-inch solid shot. When the Beaufort and Raleigh moved away, the Virginia opened fire again with red-hot shot. Smashing into the Congress, the rounds set fire to the wreckage and flames soon ate away at wood and cordage.

Buchanan climbed up to the casemate’s roof, or spar deck. He vented his outrage by taking up a musket and firing at the Yankees on the shore. While on the spar deck, a musket ball fired from shore struck the captain in the leg, severing a femoral artery. Carried below, Buchanan turned over command to Jones. Jones tried to close in on the Minnesota. The ironclad’s deep keel kept the vessel from getting closer than about one mile from the stranded frigate. Only one shot from the Virginia struck the enemy vessel. The Jamestown and Patrick Henry edged in closer and hit the Minnesota several times before they were driven off by the Union vessel’s larger guns.

Catastrophe for the Union

As dusk approached, Jones broke off the action and returned to Gosport, deciding to wait until the next day before mopping up the rest of the Hampton Roads flotilla. In the darkness, the wreck of the Congress continued to burn. March 8, 1862, was one of the most disastrous days in the history of the U.S. Navy. Nearly 300 officers and men were killed. Two frigates were destroyed, and only shallow water and the onset of nightfall prevented the destruction of three more capital ships.

In contrast to the catastrophe that struck the U.S. Navy, the Virginia’s loss was only two dead and eight wounded. Some minor damage was evident. Besides the two broken gun muzzles, Jones reported that the armor was damaged slightly, and the “anchors and all flagstaffs shot away and the smokestack and steam pipe were riddled.” The damage to the ram was not fully realized that evening; Jones wrote that “the prow was twisted” but seemed unaware that it was actually broken off and lost in the Cumberland’s hull.

“So Many Pebbles Thrown by a Child”

Meanwhile, help was near for the dispirited U.S. Navy. At 4 pm, as the battle was at its height, the Monitor passed Cape Henry. Echoes of cannon fire carried 20 miles to reach Worden and his crew. A few hours later, as bright flames flared from the Congress into the night sky, the Monitor steamed into Hampton Roads.

Lieutenant Greene took the Monitor’s cutter and visited the Minnesota. The sailors took comfort at the arrival of the “iron battery,” which they hoped would shield them when the Virginia came back. Just as Greene returned to his ship, the Congress exploded “not instantaneously, but successively; her powder tanks seemed to explode, each shower of sparks rivaling the other in its height.” He continued, “Certainly a grander sight was never seen, but it went straight to the marrow of our bones.”

Sailors worked all night to get the Minnesota afloat again, but not even steam tugs and a rising tide could budge the frigate. “The tremendous firing of the broadside guns,” wrote Captain Van Brunt, “had crowded me farther upon the mud bank, into which the ship seemed to have made herself a cradle.”

Battle resumed on Sunday, March 9. At 6 am, the Virginia came out of the Elizabeth River, followed by three gunboats. At first, the Confederates steamed past the Minnesota at a comfortable distance and headed toward Fortress Monroe. Van Brunt dismissed the hands so that they could eat, but breakfast was cut short as the Virginia turned around. When the Rebel ship closed to within one mile, the Minnesota fired her stern guns and signaled to the Monitor.

One shot from the Virginia punched through several compartments aboard the Minnesota before exploding and setting a fire. Laboring to free the Minnesota, the tug Dragon took a fatal hit when a Confederate round exploded her boiler.

Worden quickly steered toward the Virginia, intending to fight the Rebel ironclad as far away from the Minnesota as possible. For the first time, two ironclad naval vessels turned their fire against each other. From the Minnesota, Van Brunt observed that even the heaviest shot and shell affected the ironclads no more than “so many pebble stones thrown by a child.”

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Monitor

The Virginia was even slower than she was on March 8. Shot holes punched through her smokestack the day before reduced the draft needed to feed the engine fires and raise steam. Although the top speed of the Monitor was only about seven knots, she could make a turn in about five minutes as opposed to the half an hour required by the Virginia. Drawing half as much water as the larger Confederate ironclad, she could maneuver over sandbars or shallows that would trap the Virginia. Rather than having to constantly maneuver into new firing positions, the Monitor could simply stay in one spot and rotate her turret.

This is not to say that everything worked perfectly aboard the Monitor. The Yankee ironclad’s turret could swing in any direction but could not fire straight ahead without risking serious injury to the occupants of the pilot house. Early in the battle, the speaking tube linking the pilot house with the turret was knocked out, requiring officers to send messengers running back and forth.

There had been little time for the crew to get used to operating the turret and aiming the guns. Looking through the ports, gunners could see only a tiny sliver of the outside world over the barrels of the massive cannons. Before the battle, reference marks were made to aid the gunners in lining up shots at particular bearings, but the bustle of action soon wore away the marks.

Placing the turret in motion was tricky, but stopping at a precise point was proving impossible. The gunners quickly learned how to estimate the moment when the gun would bear on its target, and fire while the turret was still in motion.

“No Longer an Ironclad”

Two days of combat operations had consumed tons of coal and ammunition aboard the Virginia. This did not solve the problem of her excessive draft, but instead nearly doomed the ship. Lightening her coal bunkers did not keep the Virginia from suddenly running onto a sandbar. There had been no time to extend the armor far enough below the waterline to protect the wooden hull. Now, a band of wood planking was exposed to enemy fire. And, the rudder and propeller were now potential targets as well.

As Ramsey put it, the Virginia was “no longer an ironclad.” Without a fast escape from the sandbar, the Confederate ship would meet a similar fate to the two frigates she destroyed the day before. In the engine room, the safety valves were lashed down. The crew “piled on oiled cotton waste, splints of wood, anything that would burn faster than coal,” wrote Ramsey. Steam pressure rose to frightening levels. The propeller spun wildly, but the keel stayed stuck fast. At last, the engine crew felt a slight movement, and the massive ironclad slowly slipped into deeper water.

Mutual pounding with heavy guns proved only that neither ironclad could shatter the other’s armor. Jones thought ramming the Monitor might do the trick, and he “determined to run into her.”

Before the Virginia could reach the Monitor, the Union ship moved nimbly out of the way and received only a glancing blow. The Virginia’s attempt at ramming “left no mark on the iron except some splinters from her timbers, which are sticking to a nut and screw on her hull,” wrote a New York Times correspondent.

Lieutenant Greene remembered that one of the Dahlgrens fired a 180-pound solid round that struck the enemy’s casemate. According to their instructions, the gunners used only a 15-pound powder charge. Greene believed that a 30-pound charge, fired at such close range, could have punctured the Confederates’ armor.

No shots from either ship broke through the other’s armor. Just the same, the iron did not provide complete protection. A Confederate shell landed on the turret armor of the Monitor. Although not piercing the iron, the force of the impact knocked down three officers who were either touching the turret’s inner wall or standing close by. One officer was unfazed, but the other two were temporarily knocked unconscious.

Both ships received hits that left large dents in the armor. On the Monitor, bolts held on the armor plating. Each bolt was secured on the inside by a nut, which a shell impact could knock loose and send flying like a bit of shrapnel. A similar hit on the Virginia would crack the wooden backing behind the armor. The flying iron and wooden splinters caused no major injuries, but would remain a concern aboard later American Civil War ironclads.

Who Won the Battle of Hampton Roads?

Ramming would not sink the Monitor, and firing at the turret was futile. There was nothing else on Ericsson’s “raft” to aim for except the pilot house. This proved a more vulnerable target. About noon, a Confederate shell exploded just in front of the viewing hole in the pilot house. The blast cracked and bent a protective iron “log” that sheltered the viewing port and partly blew off the roof.

Temporarily blinded by the flash of gunpowder, Captain Worden could barely sense that light was flooding in through the damaged roof. Believing that the pilot house was wrecked, Worden ordered the helm put to starboard. They made for shallow water, where the crew could assess the damage.

Worden, his face covered in blood, was tended by the surgeon. Lieutenant Greene took command. To his relief, Greene found that the pilot house was not too badly damaged. Perhaps 20 minutes after the captain was wounded, Greene was ready to renew the battle. But, he saw that the Virginia was steaming back toward the Elizabeth River. It seemed plain enough to everyone aboard the Monitor that the “cheese box on a raft” won the battle.

Aboard the Virginia, the Confederates took an entirely different view. To them, it appeared that they had inflicted serious damage on the enemy vessel, because the Monitor pulled away and retreated into shallow water. Next, the Rebels anticipated the destruction of the Minnesota. It was not to be. The pilots warned Jones that the tide was falling, and they risked grounding once again. And, there was minor damage to see to, such as a persistent leak in the prow caused by the loss of the ram and the impact with the Monitor. Jones ordered the ship to return to the shipyard. When the Virginia passed Craney Island, the crew heard raucous cheers from hundreds of soldiers who congratulated the Confederate tars for their apparent victory.

Both sides claimed they won the Battle of Hampton Roads. The Monitor was the first to break off the fight and leave the scene of the battle. But the Yankees did return to renew the battle, and they did prevent the Minnesota from meeting the fate of the Cumberland and the Congress.

Casualties were light. No one was killed on either ship, and only five men on the Monitor, including Captain Worden, were wounded. Although dueling with wooden ships cost the Confederates almost two dozen casualties on March 8, they lost no men at all to the Monitor.

The Death of the Wooden Warship

The famous pioneer ironclads never met again in battle. Only one more major action awaited the Monitor, a failed May 12 naval attack on Confederate fortifications and batteries at Drewry’s Bluff on the James River, downstream from Richmond. Although resistant to the enemy artillery, the Monitor was unable to elevate her turret-enclosed guns sufficiently to engage the Confederate batteries.

Neither the Monitor nor the Virginia would survive 1862. Union forces moved against Norfolk in early May. On the morning of the Monitor’s unsuccessful May 12 run on Drewry’s Bluff, the Confederates scuttled the Virginia rather than risk her capture.

Late in 1862, the Monitor was dispatched to Beaufort, North Carolina, to join a Union attack against the Confederate port of Wilmington. On the stormy night of December 30, 1862, Ericsson’s historic ironclad was under tow by the Rhode Island off North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Barely capable of steaming through calm waters, the Monitor plunged up and down as waves washed over her deck. Overwhelmed by the storm, the Monitor sank at about 1 am on December 31 with the loss of 16 of her crew.

Afloat for only a few months, the Virginia needed only one afternoon to prove that wooden ships had no chance in battle against armored vessels. Ramsey rather poetically noted, “The experience of a thousand years ‘of battle and of breeze’ was brought to naught. The books of all navies were burned with the Congress.” In an instant, all of the world’s wooden warships became as outdated as Roman galleys. From that moment on, the future of naval warfare belonged to descendants of the Monitor and the Virginia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments