By Jon Diamond

The Hollywood military film devotee will remember the beginning of the epic, A Bridge Too Far, when a young British airborne officer named Fuller informs Lt. Gen. F.A.M. “Boy” Browning about Dutch Underground reports of tanks at Arnhem just prior to Operation Market-Garden. In the ensuing dialogue, Browning dismisses the reports; however, Fuller requests a low-level air reconnaissance to confirm or refute them.

After his appeal for the flight is reluctantly granted, Fuller confesses to Browning that “everybody thinks I’m overanxious, sir.” Browning retorts, “Fuller, I wouldn’t be too concerned about what people think of you. You happen to be somewhat brighter than most of us. Tends to make us nervous.”

The name Fuller was fictitious in the film’s script, ostensibly to avoid confusion. The real officer portrayed in the film was Major Brian Urquhart, of no relation to General Robert “Roy” Urquhart, commanding general of the 1st British Airborne Division. Brian Urquhart served as an intelligence officer during Operation Market-Garden. Urquhart’s rich life straddled both war and peacekeeping missions in the upper echelons of command and decision making.

Urquhart’s Accidental Enlistment

Born in England in 1919, Brian Urquhart was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford. After the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939, Urquhart returned to Christ Church, Oxford, but not to remain as a student. He noticed that a recruiting station had been established and he enlisted. Urquhart believed that he had completed a long enlistment form for the Royal Navy. He learned otherwise, when 10 days later, he was ordered to report immediately to the 164th Officer Cadet Training Unit in the Goojerat Barracks at Colchester.

He had evidently completed the wrong form and now was a member of the British Army. Urquhart felt that the need to outwit the enemy by superior guile, skill, nerve, and discipline was scarcely even hinted at during training. Minimal attention was paid to the vital subject of communications. In January 1940, after only a four-month course, he was posted as a second lieutenant to the Dorset Regiment. In the spring of 1940, Urquhart was posted away from his 5th Battalion and became intelligence officer to the brigade headquarters.

Urquhart attributed this assignment as a compliment to his acumen, knowledge of languages, and academic background. While at the Army Gas School in Tregantle in Cornwall, the Low Countries were overrun during the German blitzkrieg and Urquhart rejoined his brigade as part of the 43rd Wessex Division. It was the only fully equipped division remaining in the British Isles, being put into the General Headquarters Reserve north of London. After some time, his Dorset Regiment was transferred to the Dover area for coastal defense duties, which were quite dull and tedious to Urquhart.

In August 1941, Brigadier Browning, who was then commanding a sister brigade in the Wessex Division, was soon to be elevated to the rank of major general, airborne forces. Browning’s mission was to develop the parachute and glider-borne troops of the British Army, and he asked if Urquhart, whom he knew from the Wessex Division, would be available to join his staff as intelligence officer. Urquhart leaped at the opportunity since he had found life in an infantry brigade as “somewhat humdrum.”

Some months later, after being seriously injured in a parachute jump, Urquhart was hospitalized from August to December 1942. After that injury, Urquhart would do no more parachuting. After attending the Staff College at Camberley as a young 23-year-old, he rejoined Browning’s staff in April 1943 as GSO 2 Intelligence with the rank of major. He became the chief intelligence officer at I Airborne Corps headquarters, commanded by General Browning, at Moor Park at the age of just 25.

Receiving Word of Panzers

Admittedly, Urquhart believed Operation Market-Garden was the “most traumatic experience of my life.” Urquhart’s job was to try to evaluate what the enemy reactions were going to be and how the British paratroopers and glidermen ought to deal with them. The British airborne troops were going to be dropped at the far end of the operation at Arnhem in the Netherlands, across the farthest bridge over the lower Rhine. From the first inkling of Operation Market-Garden, Urquhart found it strategically unsound.

Urquhart became increasingly alarmed, first at the German preparations, because there were intelligence reports that two SS panzer divisions were in the operations area of the 1st Airborne Division. In fact, the primary units of the II SS Panzer Corps, the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions, had been ordered to the Arnhem area by Field Marshal Walther Model, commander of the German Western Front, on September 3, 1944. Their presence near Arnhem was reported by the Dutch Resistance and had been mentioned in Twenty-first Army Group’s intelligence summary on September 10. Dutch Resistance groups regularly provided disconcerting and coherent reports about the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions. The information usually came through the British Second Army via resistance line crossers and Dutch liaison officers working with the I Airborne Corps.

Also, shortly before the start of Operation Market-Garden, British codebreakers at Bletchley Park intercepted and decrypted a number of German messages that supported the resistance reports. These intercepts included information about the presence of an assault gun regiment and the headquarters of Field Marshal Model’s Army Group B near Arnhem. This evidence was still regarded as “thin” because the units were unidentified, with strength unknown, and no one knew whether they were being refitted or merely passing through. However, on September 5, a report specifically mentioned that the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were ordered to Arnhem to rest and refit. Amid these disparate sources of information, Urquhart “was really very shook up.”

The troops of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were veterans who had suffered heavy losses during the fighting in Normandy. Both divisions included armored elements, which significantly outgunned lightly armed airborne troops. The Supreme Allied Headquarters Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) weekly intelligence summary (produced by Maj. Gen. Kenneth Strong, the SHAEF G2) for the week ending September 16, 1944, stated that the divisions were being equipped with new tanks from a depot in nearby Cleve, Germany.

The British paratroopers carried light weapons, their primary defense against enemy armor being the PIAT (projector, infantry, anti-tank), which was a 34.5 pound device that threw a 2.5-pound bomb up to 100 yards. Also, the 1st Airborne at Arnhem was to be equipped with a few armored jeeps and 6-pounder antitank guns landed by glider. More than any other factor, the presence of crack German armored divisions rearming and refitting contributed to the virtual destruction of the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem and the strategic failure of Operation Market-Garden.

Dismissing Urquhart’s Warnings

Major Urquhart’s fears had been growing steadily in the days preceding Operation Market-Garden. Repeatedly, he had voiced his objections to the plan to “anyone who would listen on the staff.” By the morning of Tuesday, September 12, with the airborne assault only five days away, Urquhart’s doubt about Operation Market-Garden resembled near panic.

Urquhart had presented the Twenty-first Army Group’s intelligence summary, a cautious message from General Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army Headquarters, to General Browning and his operations officer, Colonel Gordon Walch. Largely because Dempsey’s report lacked any kind of confirmation and was, therefore, deemed vague, Urquhart recalled, “They said that I should not worry unduly, that the reports were probably wrong, and that in any case, the German troops were refitting and not up to much fighting.”

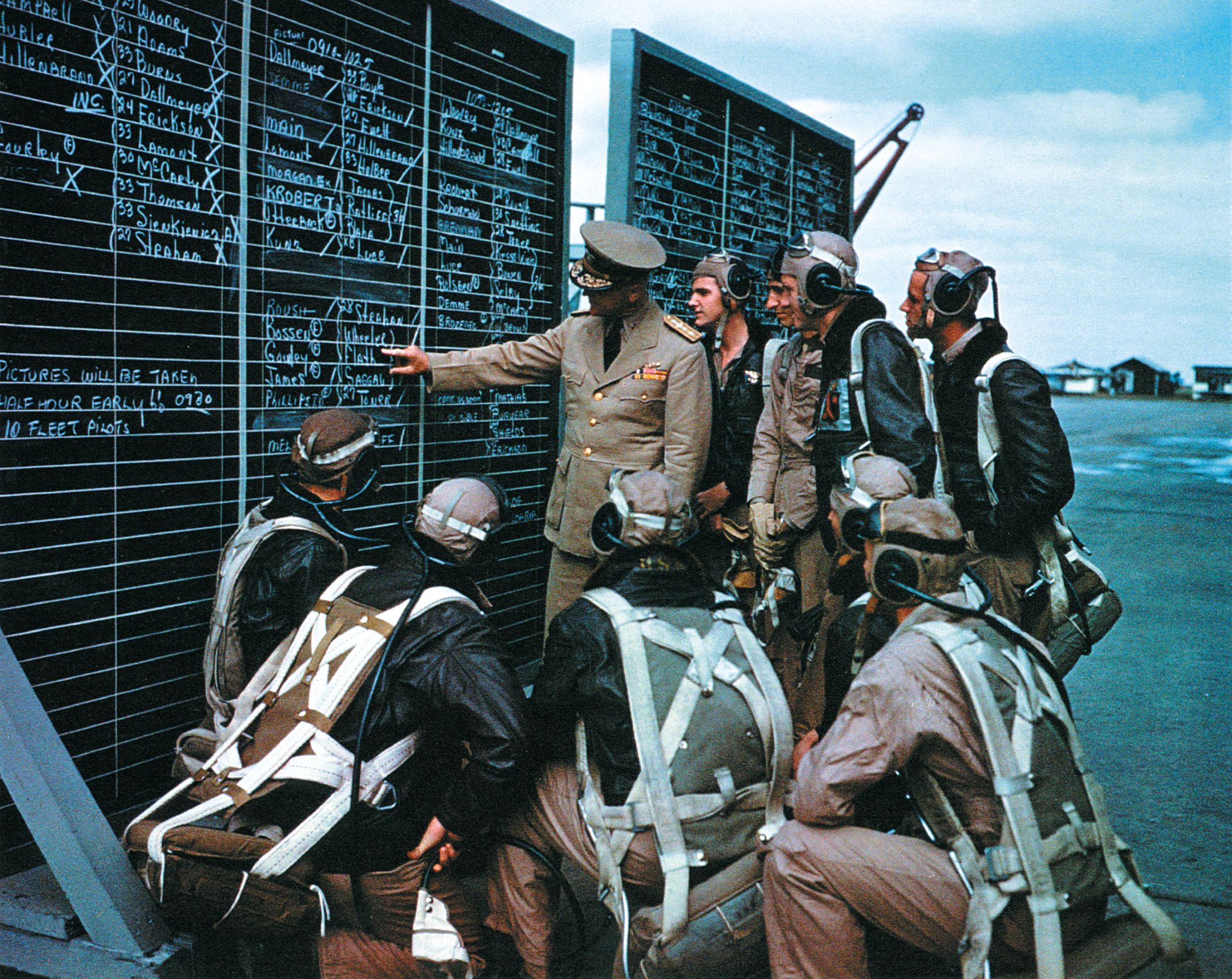

Urquhart arranged for a photographic reconnaissance of the area by Supermarine Spitfire aircraft and was able to identify armored vehicles in the resulting photographs. When he rushed five oblique-angle pictures from an “end of the run” strip taken by one of the Spitfires, the general was unimpressed. Hundreds of aerial photographs of the Arnhem area had been taken and evaluated in the previous three days, but only these five shots showed the unmistakable presence of German armor. Browning said, “I wouldn’t trouble myself about these if I were you. They’re probably not serviceable at any rate.”

Unlike Browning and others at I Airborne Corps headquarters, General Walter Bedell Smith, chief of staff to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, took the matter gravely enough to recommend strongly that not one but two airborne divisions be employed at Arnhem to counter the threat. With Eisenhower’s permission, Smith personally voiced his concerns to British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who “ridiculed the idea and waved my objections airily aside.” Thus, Montgomery failed to take either the intelligence or its implications seriously. Others were likewise concerned, but their opinions went unheard in the run-up to the launch of Operation Market-Garden.

Browning dismissed Urquhart’s warnings as those of a “nervous child suffering from a nightmare.” Urquhart was unaware that some members of Browning’s staff considered the young intelligence officer almost too zealous. Urquhart’s pessimistic warnings irritated them.

Placed on Medical Leave

On September 15, two days before the airborne landings, the Airborne Corps medical officer visited with Urquhart and told him he was “suffering from acute nervous strain and exhaustion,” and ordered him to go on immediate leave or face court martial.

Urquhart himself was worried about the state of mind of the senior officers in the British I Airborne Corps headquarters, who were all extremely gung-ho and were talking about Christmas in Berlin. Some officers joked about taking their golf clubs because the operation was going to be a pushover.

Urquhart remained concerned and later stated, “I tried to get this point of view across and pointed out that if we were going to do it properly, we were going to have to drop the troops in a different place so that they could immediately capture the bridge, and that there was a big question as to whether the relieving troops could get up from Brussels in time.”

British XXX Corps, under Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, was stuck on the Albert Canal, which was 60 miles away, and the Dutch countryside was polder, essentially flat land kept dry by a centuries-old system of dikes. Urquhart stressed, “The roads were all causeways, which are ideal for an armored force to stop another from advancing. All you’ve got to do is to disable one tank, and that blocks the whole thing. I simply did not believe that the Germans were going to roll over and surrender. Well I didn’t get anywhere with this. Everyone thought that I was hysterical, nervous, and so on.”

After General Browning boasted to Prince Bernard of the Netherlands that the Allied forces were going to advance into Germany over a carpet of airborne troops, Urquhart said to his operations officer, Colonel Walch, “I wonder if they’re going to be alive or dead airborne troops.”

Urquhart believed that Browning’s metaphor of an “airborne carpet for the ground forces” lulled many commanders into “a passive and absolutely unimaginative state of mind in which no reaction to German resistance, apart from dogged gallantry, was envisaged.” The pessimistic commentary did not go over well for Urquhart, and it hastened his being sent away on medical leave.

Leave Cut Short

Certainly, Brian Urquhart cannot have been thought very ill because nine days later he was summoned and flown at short notice to Brussels to join Browning’s headquarters to help sort out the mess he had so vociferously warned about. Urquhart did not know why he was ordered to return at this juncture and assumed that in the debacle that Operation Market-Garden had become it looked odd for the I Airborne Corps chief intelligence officer to be absent on sick leave. Urquhart was greeted warmly by Browning and his old comrades, but he could not help noticing that talk about the current military situation was kept to a minimum. He noted that the atmosphere was very different from the triumphant and confident tone of the previous weeks.

Some have contended that it was Browning’s management style that accounted for the omission from the intelligence summary in the Operation Market-Garden plan of the references to panzer troops that were found in the plan for an earlier operation, codenamed Comet, that had also been aimed at the same bridges over the Maas, Waal, and Lower Rhine Rivers.

After the war, General Roy Urquhart of the 1st Airborne that was decimated at Arnhem complained that his intelligence staff had been scratching around for “morsels of information.” He was informed by Browning that his division was not likely to encounter more than a German brigade supported by a few tanks. The beleaguered 1st Airborne Division had held on at Arnhem against enormous odds for five perilous days, but when it became clear that they were not going to be relieved, what was left of the division was ordered to get across the river by night, leaving the wounded behind.

Out of 10,005 men, only 2,163 were evacuated in this way; 1,200 men were dead and 6,642 were missing, wounded, or captured. Many paratroopers were hidden by the Dutch and escaped months later. Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands later remarked sardonically, “My country can never again afford the luxury of another Montgomery success.”

“It was Described as a Party”

Long after the war, Urquhart realized that the generals, great commanders, and politicians involved, who were so admired during the war, were just like everyone else. “They were vain, they were ambitious, they very often made extremely faulty judgments.”

Urquhart remembered that General Browning, perhaps reflecting Montgomery’s views and those of “several other British commanders, was thinking about another great breakthrough.”

Comparisons were constantly being made between the current situation and the collapse of the German Army on the Western Front in the autumn of 1918. At planning conferences, Urquhart observed “the desperate desire on everyone’s part to get the airborne into action.” He was appalled at the lighthearted metaphors such as, “it was described as a ‘party’—used in reference to Operation Market-Garden.”

Urquhart did not feel quite the same after the war, relating that his candid postwar appraisal of the personality flaws among his superiors came later. He had previously regarded the British military hierarchy as if “they were kind of super-people. I never again trusted famous, glamorous leaders to resist vanity and ambition and make the right mature decision, and get it right.”

Just prior to Operation Market-Garden, Urquhart concluded that Browning’s ambition to command in battle was a major factor both in the conception of the operation and in his refusal to take the latest news on German opposition seriously. Urquhart believed that in his assessment, he may have done Browning an injustice. After the publication of Cornelius Ryan’s A Bridge Too Far, he learned that Operation Market-Garden was the “offspring of the ambition of Montgomery, who desperately wanted a British success to end the war.”

According to Urquhart, Browning himself, in expressing his doubts about the wisdom and scope of the operation, had used the phrase that Ryan took as the title of his book.

Moving Past Arnhem

After the Battle of Arnhem, Urquhart requested to transfer out of the I Airborne Corps as soon as possible. Browning said that he regretted Urquhart’s desire to leave but understood fully. Browning wrote a letter to Urquhart on his departure suggesting “that it might be as well if our disagreements remained a private matter between us.”

Urquhart agreed with Browning. The last thing he wanted was to talk or write about the disaster. Urquhart left the I Airborne Corps “because I was pretty unpopular there. It’s unpopular enough to be the one person who opposes something that everybody else wants to do. But if you turn out to be right, you get seriously unpopular.”

Urquhart admitted that it is “inconceivable that the opinion of one person, a young and inexperienced officer at that, could change a vast military plan … Once a group of people have made up their minds on something, it develops a life and momentum of its own which is almost impervious to reason or argument. This is particularly true when personal ambition and bravado are involved. In this case even an appeal to fear of ridicule and historical condemnation would not have worked. The decision had been taken at the highest level, and a vast military machine had been set in motion. The opinions of a young intelligence officer were not going to stop it.”

The Arnhem tragedy had a permanent effect on Urquhart’s attitude toward life: “I never again could quite be convinced that great enterprises would go as planned or turn out well, or that wisdom and principle were a match for vanity and ambition.”

A Career Devoted to Human Rights

After his transfer, Urquhart took over an armored car squadron, which was to move slightly ahead of the Allied advance and take German scientists and industrialists into Allied custody. He and his squadron arrived at the Belsen concentration camp “more or less by a mistake because we didn’t get the radio message telling all the troops to stop.”

After the Belsen experience, Urquhart felt strongly that human rights were something that simply had to be developed into an international rule. It was not good enough, he said, to try to “rely on people to behave reasonably well: they don’t.” The Nazis were an extreme, but they were not unique.

After the war, Brian Urquhart’s professional life was a history of the United Nations itself. He was personal assistant to the first secretary-general, Trygve Lie, and subsequently served in various capacities, including working with Ralph Bunche, the winner of the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize, between 1954 and 1971. After 1972, Urquhart was one of the principal political advisers of the UN secretary-general and served as the under-secretary general for special political affairs working on Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Namibia, among others. He retired from the United Nations Secretariat in 1986.

There is some doubt about Urquhart’s recollection of the infamous recce photos. Seb Ritchie of the RAF Air Historical Branch does a superb analysis of the air aspects of Market Garden and this story. The book is, imho, essential reading if you’re interested in the Arnhem element of Market Garden.

Sebastian Ritchie, Arnhem: Myth and Reality.