By Dr. Carl H. Marcoux

American soldiers of Japanese ancestry made remarkable contributions to the Allied victory during World War II. The best known of their exploits was the outstanding fighting record compiled by the 100th Infantry Battalion and later the 442nd Regimental Combat Team during the European campaigns. The soldiers of the 442nd received more decorations than those of any unit in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

Less well known were the World War II contributions made by Nisei (American-born children of Japanese immigrants) troops on the other side of the globe in the Pacific and the China-Burma-India Theaters. The U.S. Army kept their service classified as secret until 1973 when the Freedom of Information Act finally provided the vehicle for the public release of this fascinating story. What were the reasons for this delay? Certainly, the story of the hazardous and valuable contributions of this group of soldiers merited the attention of the American public much sooner than 28 years from the war’s end to the ultimate release of the information.

During the course of the war, some 6,000 AJAs (Americans of Japanese Ancestry) provided valuable language and information skills for Allied military and naval personnel throughout the Asian and Pacific areas. Their efforts proved to be doubly dangerous since, because of their racial identity, they could be mistaken for enemy soldiers by their own forces. In many cases, the linguists had to be provided with heavily armed bodyguards to keep them out of harm’s way. On several occasions, Nisei soldiers were taken captive by their own comrades in arms who were unaware of the role played by the AJAs in defeating the enemy. It is believed also that in more than one situation the Japanese Americans involved in frontline action were killed accidentally by friendly fire because of mistaken identity.

The MISLS

Prior to the commencement of World War II itself, the U.S. War Department recognized the need for developing a facility capable of translating the Japanese language—to monitor broadcasts, translate documents, and to communicate, if necessary, with the Japanese. One of the world’s most difficult tongues to master, Japanese was known and understood by few Americans. However, there were 200,000 American-born Japanese and their parents living in the United States. Unless born in the United States, Asians, by law, were excluded from citizenship, so most of the Issei, the foreign-born parents of the Nisei, could not change their legal status.

It was from the pool of Nisei that the War Department planned to recruit Japanese language experts. It ordered the testing of the nearly 4,000 AJAs serving in the Army at that time to determine their competency in Japanese. As it turned out, few of the young soldiers could read, write, or speak that language with any fluency. Most had made, to a greater or lesser degree, the transition to “the American way of life.” English had now become their principal language. The U.S. Army, depending on two Caucasian officers who knew Japanese, Lt. Col. John Weckerling and Captain Kai Rasmussen, established what came to be called the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) at Crissey Field, on San Francisco’s Presidio Army base.

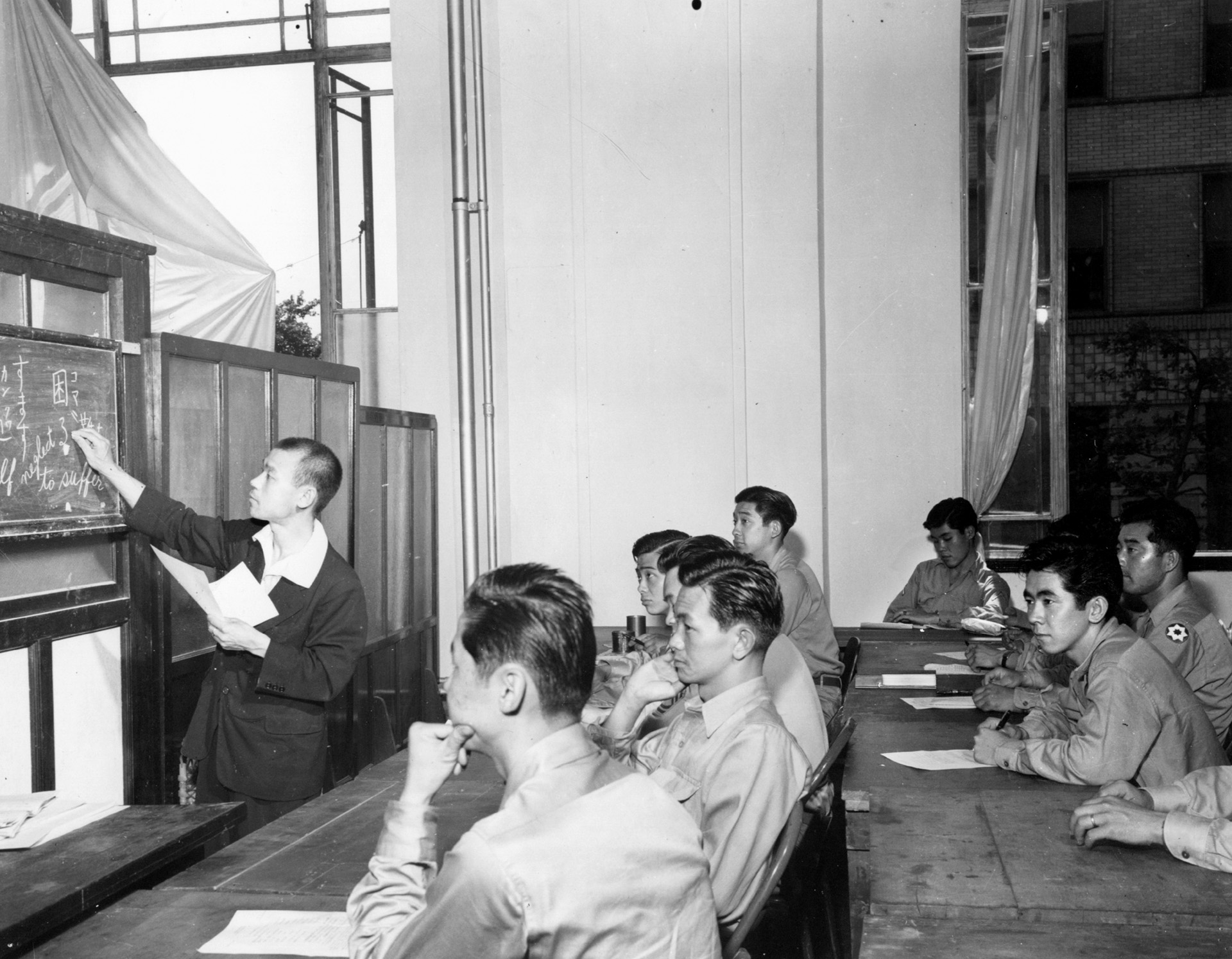

Weckerling and Rasmussen, in turn, began to recruit Nisei instructors to lead the classes. John Aiso, of Burbank, California, and a Harvard Law School graduate, became the school’s chief instructor. He was followed by Akira Oshida, Arthur Kaneko, and Shigeya Kihara, who managed to locate the necessary written materials for class use. In the short span of six weeks, the team assembled a staff, an initial class of students, and the buildings and supplies needed to begin the project.

The first class of 60 students at the Presidio commenced its studies on November 1, 1941. Fifty-eight members of the initial group were Japanese Americans. Two Caucasians with previous language training completed the first cadre. Five weeks later, the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor and other U.S. military installations on Oahu. Military authorities seemed confused as to the future of the new language school. The Army pulled both Weckerling and Rasmussen from the project and assigned them to other jobs. Fortunately, some Army officers realized the importance of the work that had begun and ordered Rasmussen back to the Presidio. The Danish-born immigrant with a native ability for learning foreign tongues remained head of the language training program thereafter.

The curriculum was designed to improve the students’ ability to communicate verbally, to read and understand Japanese military terminology and documentation, to translate intercepted radio messages, to read maps, and to understand the basics of cryptography. Later in the war, the school’s graduates proved effective in what came to be called “cave flushing,” the persuading of Japanese soldiers and civilians hiding in caves in combat areas to surrender rather than resist or commit suicide.

Recruiting Nisei in a Time of War

After the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, requiring all Japanese Americans, whether foreign born or American citizens, to vacate the coastal areas of the western states and enter some 10 relocation facilities, dubbed by some critics of the program as concentration camps. In accordance with this policy, the Army established a new facility for the language school at Camp Savage, Minnesota. Rasmussen began a desperate campaign to find Nisei with sufficient knowledge of the Japanese language to undergo the planned intensive training. Soon the demands for the expansion of the program resulted in its being moved to more adequate headquarters at nearby Fort Snelling, a permanent Army installation.

Rasmussen shouldered the task of selling recruits on the importance of the mission. His candidates often had whole families confined to the relocation facilities, living under extremely trying conditions. Nevertheless, he managed to acquire recruits for a variety of reasons. Some candidates felt that participating in the program would demonstrate their loyalty to the United States. Others felt that the language program would at least get them out of the relocation camps and could possibly open up other opportunities. By the fall of 1944, almost 1,800 students had completed extensive training in a variety of courses that would prove useful to the American military.

As the graduates streamed out of the Minnesota facility, they received assignments throughout the Pacific, from the Aleutian Islands campaign in the far north to General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters in Brisbane, Australia, which became the center for the ATIS (Allied Translator and Interpreter Service). At its peak the facility had over 3,000 AJAs serving at that location. The other two major centers for the assignment of the Nisei language specialists were JICPOA (Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area) in Hawaii and SATIC (Southeast Asia Translation and Interrogation Center) in New Delhi, India. From these key facilities the AJAs were sent to various subordinate units and on special missions.

The need for language school graduates far exceeded the supply, and Rasmussen became increasingly desperate to find candidates. He turned to the Japanese Hawaiians, for this group contained a far larger number of Kibei, American citizens who had been sent by their families to study in Japan, than the AJAs living on the mainland. The Kibei could be expected to quickly learn the curriculum developed at the Minnesota facility. The Hawaiians proved to be a hard sell. Many of them preferred to serve with the 100th Infantry Battalion, consisting of Nisei from their home territory.

Facing Discrimination within the Armed Forces

General MacArthur, commander of U.S. forces in the South Pacific, had a great deal of respect for and confidence in the language specialists. He counted on them heavily to interpret all Japanese military documents that fell into Army hands. The translation of these often critical documents aided in the planning of future campaigns.

Ultimately, the AJAs would serve in every major area in the Pacific and the China-Burma-India Theaters throughout the war and act as language experts for Australian, British, Indian, and Chinese troops, as well as for their fellow Americans. The Commonwealth troops and the Chinese had no Japanese language specialists of their own.

The Military Information Specialists, MISers as they came to be called, all served in the Army. The Navy, clinging to archaic patterns of racial discrimination, refused to allow Nisei to enlist in its branch of the service. The same practice existed for the Marines as well. As a result, those two branches later came to depend on borrowed MISers from the Army on a temporary basis whenever the need arose. More than 100 were assigned to the Marines during land campaigns under such an arrangement. Yet. the role that the MISers played in the battles never appeared in Marine dispatches.

Linguists as Interrogators

Initial attempts to draw information from Japanese prisoners of war proved difficult. Capturing them alive was a major problem itself, for the Japanese soldier had been programmed to fight to the death. The Army managed to take only 28 prisoners, about 1 percent of the defenders, when the Japanese were driven from the Aleutian island of Attu. The ferocious fighting that took place on Iwo Jima resulted in only 38 prisoners. Having once secured a prisoner, however, the interrogators quickly learned that he would respond to kind and courteous treatment. Often the simple act of offering a cigarette, some medicine, a glass of water, or a small bandage for a wound would establish a mood of cooperation during the captor’s search for critical military information.

As the war progressed, the language specialists became increasingly effective in the art of persuading Japanese soldiers both to surrender and to divulge vital military information. The Japanese Army had apparently never taught its soldiers how to conduct themselves as prisoners of war since their military ideology stressed either victory or death in battle.

Nisei as a Tactical Asset

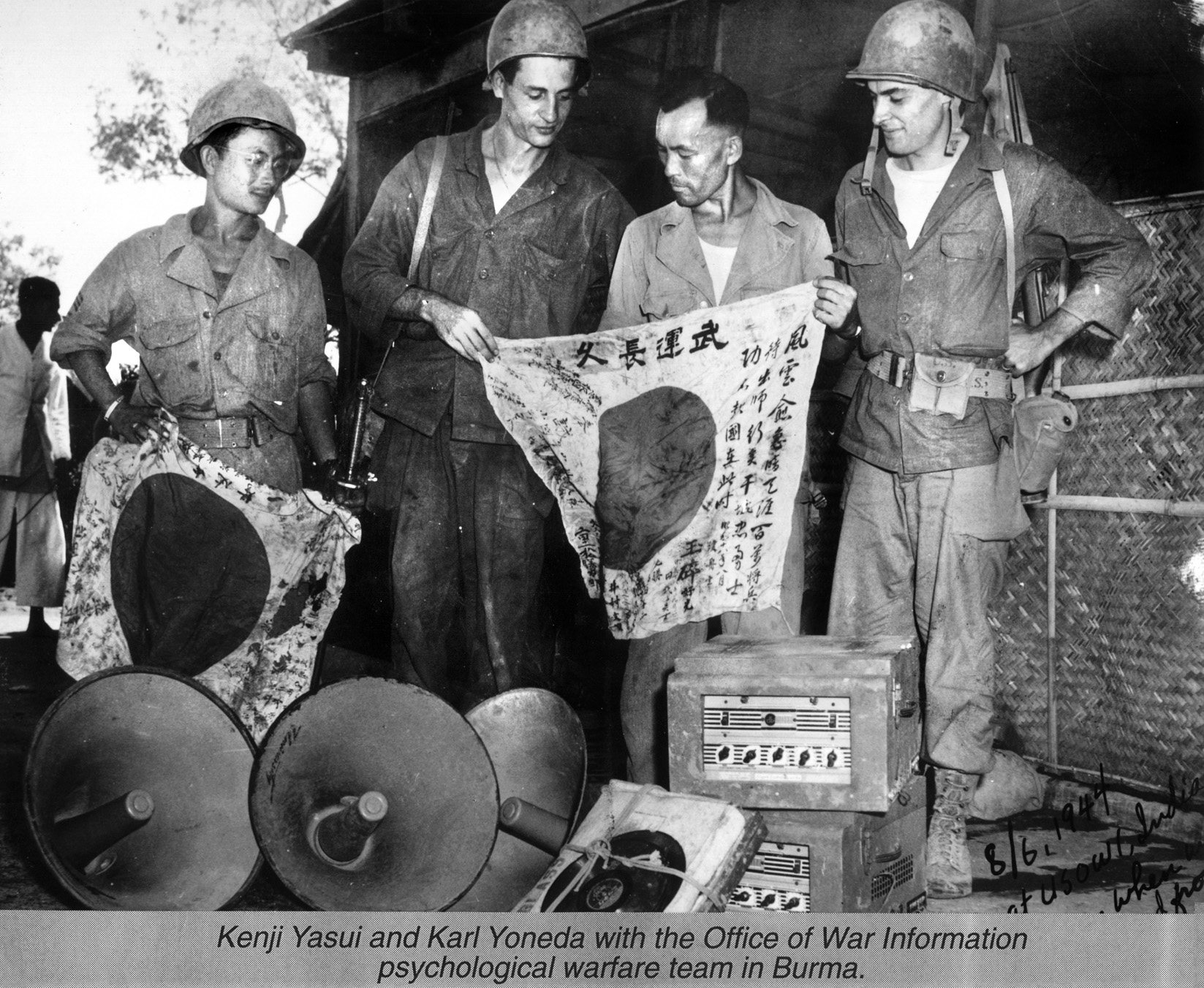

Nisei translators accompanied the Army throughout the campaign in the South Pacific. They served at Guadalcanal, the Solomons, the Carolines, New Guinea, and the Philippines, as well as in smaller and more limited engagements. MISers also accompanied the fabled Merrill’s Marauders during their raids behind Japanese lines in Burma. They performed the same service for the British Chindit guerrillas as well. A specially trained group of Nisei language experts joined OSS (Office of Strategic Services) commandos who worked with the Kachins, native Burmese fighters from the country’s northern hills. These guerrillas aided the Allies in their mission to open the Burma Road to resupply China with critical war materiél.

On the Front Lines in Okinawa

Possibly the most outstanding performance by the Nisei in the Pacific Theater took place during the struggle for Okinawa. This central island of the Ryukyus, some 350 miles south of the Japanese Home Island of Kyushu, represented the key to the southern defenses of the Japanese empire. To the advancing Allied forces its capture would provide an ideal staging area for the invasion of Japan itself. The fight for the island would prove to be the greatest battle of the Pacific War.

The Japanese 32nd Army defended Okinawa. Its commander, Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, led a force of some 75,000 Japanese soldiers plus an additional 25,000 or so Okinawans organized into a Boetai or Home Guard. These defenders were situated in an extensive system of fortified caves and underground tunnels, awaiting the arrival of the invading American Tenth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner. The total American force—ships, men, and equipment— numbered over 500,000 men, of which 180,000 assault troops (five Army and three Marine divisions) would actually go ashore.

The MISers’ contribution to the invading army’s ultimate success in capturing Okinawa was substantial. A copy of the Japanese Army’s final defense plan was captured early in the fighting. Also discovered was a contour map of the island, which was found on the body of an enemy artillery observation officer. The translation and reproduction of these critical documents by the language specialists proved to be of immense value to the American forces.

Okinawa presented a unique challenge to the language specialists. The island’s native inhabitants spoke a local dialect unfamiliar to the ears of most of the MISers unless their parents were originally from the island. The 450,000 Okinawans had also been warned by Japanese Army personnel that they would be raped, tortured, and killed by the invaders. In many cases, the civilians followed the Japanese as they began their retreat in the face of the powerful offensive launched against them by the Americans. Many chose to hide in caves and the tunnels. The job of the MISers consisted of trying to talk both the Japanese soldiers and the Okinawan civilians into surrendering.

Most Japanese soldiers chose to commit suicide rather than surrender, and they had urged the island’s civilians to do likewise. During fighting on the island of Saipan in the Marianas, many of the island’s civilians had committed suicide by hurling themselves off 800-foot cliffs into the sea. More than 50,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians died as the U.S. Army seized control of Saipan.

For the Okinawa campaign, the Army followed the suggestion of a MISer whose parents were Okinawan and set up a special unit proficient in that dialect. As the invasion progressed, the group worked to get the island’s civilians away from the fighting. They also quickly identified any Japanese Army personnel who sought to escape capture by trying to blend in with the Okinawan civilians.

Some of the Okinawan language specialists became “cave flushers.” One heroic member of this group entered a cave and convinced its inhabitants, 350 Japanese officers and men, to surrender. Another MISer entered a total of 12 different caves and persuaded the holdouts in 11 of them to surrender.

Without question, the work of these Nisei translators saved thousands of lives, among both the Okinawan civilian population and the Japanese military. By the time the Americans secured the island, some 10,000 soldiers had given up in the only meaningful mass capitulation by the Japanese military of the entire Pacific War. About 300,000 civilians, approximately two-thirds of the island’s population, also survived the holocaust. While it was true that many Japanese soldiers and some Okinawan civilians still chose to commit suicide rather than surrender to the American forces, there is no doubt that the toll would have been much higher were it not for MISer efforts.

A Postwar Role

The work of the Nisei translators was not concluded at war’s end. They traveled throughout the Pacific, participating in the surrender of Japanese troops on small islands and in major cities. They moved quickly to POW camps as well to ensure the safety of Allied troops in Japanese hands. They also acted as interpreters during the war crimes trials of Japanese soldiers that followed in the Philippines and Japan. Their postwar contributions proved equally as important as their wartime efforts.

The Army sought to hold on to as many AJAs with Japanese language skills as possible following the war because the United States needed their skills during the occupation of Japan. Many Nisei chose to make a career in the Army, receiving advancement in the officer structure as time passed, before eventually retiring.

Legacy of the MISers

The MIS linguists earned three Distinguished Service Crosses, five Legion of Merit medals, and five Silver Stars. They also received numerous Bronze Stars, Soldier’s Medals, and Purple Hearts. In total, 39 MIS personnel gave their lives in the service of their country.

During the war and for many years thereafter, the American public knew little about the service provided by the MIS linguists to the Allied forces. During the war, many MISers had relatives still in Japan, some even in the Japanese Army. The U.S. Army sought to protect the identity of the translators, so as not to bring harm to these family members. There has also been a natural reticence on the part of the Nisei themselves to discuss their accomplishments while in the service. However, General George Willoughby, MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, estimated that the work of the MISers shortened the war in the Pacific by two years.

The MISLS was moved to Monterey, California, after the war, and the language center has grown significantly since it began in 1941. It has remained the major U.S. facility for the instruction of foreign languages for military purposes. More than 100,000 students have passed through the school to date. It currently offers instruction in 50 different languages and has a library of 20,000 volumes on site. In January 2000, the Allied Translator and Interpreter Service finally received a Presidential Unit Citation from the secretary of the Army.

Dr. Carl H. Marcoux is a World War II veteran of the U.S. Merchant Marine and a Korean War veteran of the U.S. Air Force. He resides in Newport Beach, California.

Did two tours at the Defense Language Institute, first as a student, then many years later as an associate dean. There are buildings named after Weckerling and Rasmussen at DLI.