By William E. Welsh

With his one good eye, French King Philip II looked east down the straight line of an old Roman road in the disputed county of Flanders on Sunday, July 27, 1214. The French monarch was trying to get the last of his troops across a bridge that spanned the Marcq River at a hamlet called Bouvines. Throughout the first half of the year, Philip’s army had ravaged Flanders, but now a mighty host led by Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV and bankrolled by the English crown had crossed the Flemish border, determined to thrash Philip’s army and seize Paris.

When he learned that the enemy was on the march, Philip quickly fell back in search of firmer ground on which his knights could maneuver. As he waited for his rear guard to catch up, the 49-year-old king shed his heavy chain mail, wiped the sweat from his bald head, and sat down in the shade of an ash tree, where he refreshed himself with bread dipped in wine.

Before long his most trusted adviser, Brother Guerin, bishop-elect of Senlis, came riding up the road and related what he had just seen. Garbed in the robe of a Knight Hospitaler, Guerin informed the king that the enemy had draped its horses in armor. Both he and Philip knew what this meant—the enemy intended to give battle soon, despite the usual reluctance of medieval armies to fight on the Sabbath. The king summoned his barons and held an impromptu council of war. He had two choices. He could try to get the remainder of his army safely across the bridge, or he could recall his vanguard from the west bank and reform his army with its back to the river. If he did not make a decision soon, his divided troops would be ripe for slaughter.

The Capetian Kingdom

The looming battle had been a long time coming. When Philip was crowned on November, 1, 1179, the kingdom he inherited was like a coin clutched loosely in the hand of a child. Although Philip’s father, Louis VII, was still alive at the time the young prince was crowned, the older man’s health was rapidly failing, and he had lost the strength to rule. The Capetian kingdom that Philip inherited consisted of the Ile de France, a slender finger of territory that included Paris and Orleans to the south. More than half of France belonged not to the French House of Capet, but to King Henry II of England, a savvy monarch who had expanded his territory on the Continent through his marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Henry had inherited the territories Normandy, Anjou, and Maine from his parents, and when he married the Duchess of Aquitaine in 1152, he added her lands to his realm as well.

From the moment he was crowned, Philip focused on expanding the borders of his beleaguered kingdom at Henry’s expense. Fortune played into his hands when three of Henry’s four living sons rebelled against their father in 1173. The sons, who were unhappy over the terms of the proposed will their father drafted for his succession, required a safe haven and a base from which to launch their rebellion. France stepped in.

The sons’ revolt, which was aided by Louis VII, ended in failure the following year, and Louis negotiated a settlement with Henry in October 1174. Still, the rebellious princes continued to scheme against their father. After Henry the Younger and Geoffrey died from sickness in 1183 and 1186, respectively, it fell to Prince Richard to continue the brothers’ rebellion. Meanwhile, Philip attacked east, and by 1186 he had grabbed several key territories in a five-year struggle waged alternately against Flanders, Champagne, and Burgundy. In 1189, Philip and Richard joined forces and drove Henry from his base camp at Le Mans, eventually capturing Tours. Henry died in July and was succeeded by Richard, now called Richard the Lion-Hearted.

The following year, Philip and Richard departed for the Holy Land on the Third Crusade. Throughout the initial stages of the campaign, the two monarchs quarreled at every turn. During the siege of Acre, Philip lost an eye. Half-blind and suffering from severe dysentery, he decided to return to France after Acre fell to the crusaders in July 1191. The king’s decision to leave the crusade was made as much for political as health reasons. At the time, the succession of the count of Flanders was in question, and Philip was anxious to return and settle the matter in a way that favored his own kingdom.

War Between Philip and “Blunt Sword”

Philip made it safely home, but Richard was not as lucky. While returning overland to England, Richard was captured and imprisoned by the Duke of Austria for several years before being ransomed in 1194. Upon his return to England, Richard learned that Philip had been slowly chipping away at his holdings on the Continent. For the next five years, the two monarchs waged unremitting war against each other. Richard won nearly every encounter. Philip’s reversal of fortune did not end until Richard was fatally felled by a crossbow bolt during the siege of Chalus in 1199.

Richard was succeeded by his younger brother, John. Philip immediately took up the sword against John and, unlike his struggles with Richard, enjoyed considerable success against him in the field. The two agreed to a truce in 1200. By the terms of the Treaty of Le Goulet, Philip agreed to recognize John as Richard’s rightful heir. In turn, John agreed to recognize that the counts of Boulogne and Flanders were Philip’s vassals. John also agreed not to provide financial aid to the increasingly restive Holy Roman Emperor Otto, who was John’s nephew.

A series of territorial disputes sparked the flame of war anew in 1204. Over the next two years, Philip conquered Normandy and annexed Brittany, Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. John, having been bested by the more experienced Philip in nearly every engagement, returned to England in 1207. Despite the large areas that he had lost to the French king, John retained Poitou and Gascony. For his military ineptitude, John was mockingly called “Blunt Sword” by his subjects.

The Excommunication of John

While Philip was busy expanding his kingdom, he was also mired in a dispute with Pope Innocent III. The 37-year-old Italian had been elected pope in 1198. By the time Innocent became pope, Philip was married to his third wife, Agnes of Merania. But his estranged second wife, Ingeborg of Denmark, was still living in France. When she appealed the injustice of her circumstances to Innocent, he sided with her and placed a papal interdict on France. After some negotiations, Innocent agreed to lift the interdict in 1200. The following year Agnes died, and Philip agreed to take back Ingeborg as his wife. Philip had no love for her, but he bowed to the pope’s wishes, knowing that he would need his political support in the ongoing war against England.

While Philip was busy mending fences with Pope Innocent, John triggered a major dispute with the pope in 1207 when he expelled the Canterbury Cathedral chapter of the church and confiscated its treasury. Angered by John’s action, Innocent placed England under an interdict in 1208, and the following year he excommunicated John from the Catholic Church. By then, Philip was back in the pope’s good graces, and John was the focus of His Holiness’s ire.

The Many Enemies of King Philip

The attention of both monarchs, as well as the pope, was keenly focused on the matter of who would succeed Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, who had died unexpectedly at the age of 32. At the time there were two rivals for the title of emperor: Philip of Swabia, Henry VI’s brother, and Otto of Brunswick, who was John’s nephew. Not surprisingly, the English king backed Otto, while the French king backed Philip of Swabia. When Philip of Swabia was murdered by one of his enemies in 1208, Philip switched his allegiance to 14-year-old Frederick Hohenstaufen. The balance was tipped to Otto’s advantage when Innocent decided to back him, under the mistaken assumption that Otto would stay out of politics on the Italian peninsula.

Otto’s father was Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria and Saxony, and his mother was Matilda Plantagenet. Born in Normandy, Otto was raised in England under the watchful eye of his grandfather, Henry II. Following the death of Philip of Swabia, Otto was crowned king of Germany, and the following year he traveled to Rome, where Innocent bestowed on him the title of Holy Roman Emperor. From that moment on, Otto began to plot his revenge against Philip, who had annexed a large portion of his uncle’s lands on the Continent and had supported his rivals inside Germany. John assiduously courted Otto’s allegiance to give him an ally on the Continent who was capable of leading an army and defeating Philip.

Philip had other enemies in addition to John and Otto. The foremost of these was Renaud, Count of Boulogne, who had been in power since 1191. A longtime ally of the English with close ties to Normandy, Renaud was forced by the Treaty of Le Goulet to serve as Philip’s vassal. In an attempt to strengthen their ties, Philip proposed a marriage between his son and Renaud’s daughter. In addition, he gave Renaud three counties in Normandy.

The king’s effort to control the political fortunes of Flanders and bring it under his sway were more overt and heavy handed. When Baudouin, Count of Flanders, and his wife Marie died on the Fourth Crusade, Philip took custody of their two daughters. The eldest, Jeanne, whose dowry included Flanders, was wed in 1212 to the Portuguese Prince Ferrand. Around the time of the marriage, Philip seized several parcels of Flanders that he had lost to Baudouin in previous wars. Philip’s use of military force did not sit well with Ferrand or his betrothed.

Cross-Channel Hostilities Open

As he had done with Philip and John, Innocent soon clashed openly with Otto. When Otto tried to extend his power into southern Italy, the aggressive pope excommunicated him in 1211. Otto’s excommunication laid the groundwork for a rival king of Germany. Supported by both the pope and Philip, Frederick Hohenstaufen was able to gain enough domestic support to be crowned king of the Germans on December 11, 1212.

Meanwhile, the hatred felt toward Philip by some of his most powerful subjects was coming to a boil. The drift to war increased when Renaud, unable to recover the lands Philip had compelled him to assign to his new son-in-law in 1210, appealed to Otto for support. When Renaud refused to hand over the stronghold of Mortain, Philip seized it by force in September 1211. Renaud subsequently met with Otto in March 1212 in Frankfurt, and Otto offered to arrange a meeting between the unhappy count and John. Two months later, in May 1212, Renaud traveled to England, where he and the English king signed a mutual assistance agreement in which John would pay Renaud 1,000 pounds sterling annually and Renaud would become his vassal and assist him if a fresh war broke out between England and France.

That June, Philip confiscated all English ships in French ports, and John responded in kind by seizing all French ships in his ports. These moves marked the formal outbreak of yet another war between the two countries. By this point, Innocent had resolved to enlist Philip’s help in an effort to forcibly remove John from the English throne. In Innocent’s thinking, the campaign against John would be a crusade to free the Roman Catholic Church in the British Isles from the tyranny of the English king. At a great council held in Soissons on April 8, 1213, Philip met with his loyal barons and plotted a seaward invasion. Philip designated 26-year-old Louis to lead the invasion, which he estimated would require 1,500 ships to transport the army across the Channel and defeat the English fleet. The fleet assembled at Boulogne in May and from there shifted to Gravelines and Damme, the commercial harbor serving Bruges.

John planned to assail Philip from both the east and west. From the east, Otto would lead an army that included mostly Imperial forces, augmented by contingents from England and discontented barons whose lands were sandwiched between the Holy Roman Empire and France. From the west, John would invade the Continent and begin the slow process of recovering his hereditary lands. English coins funded both armies.

To start a new military campaign against Philip, John felt that he needed to patch up his differences with Pope Innocent. He met in May with a papal legate named Pandulf and agreed to abide by the pope’s word and become his vassal. The reconciliation was a deft diplomatic move on John’s part and brought him renewed support among his unhappy people.

While the French fleet was still at Gravelines on May 22, Pandulf conveyed Innocent’s order for Philip to abandon his invasion of England. Whether Philip intended to continue the invasion and defy the pope’s wishes is unclear, but events soon forced him to abandon the invasion. While Philip was busy consolidating his territorial gains in Flanders, an English fleet led by William, Earl of Salisbury, swooped down on the French fleet on May 30 at Damme, destroying a number of vessels and scattering the rest. French forces managed to repulse a land raid by Salisbury, and the English retired to an island off the coast of Flanders. Philip, in a cold rage, turned his attention to conquering Flanders. Throughout the second half of 1213 and into the following year, Philip conducted a steady campaign of siege warfare in Flanders.

Philip Crushes Flanders

Like Renaud, Ferrand was driven into the arms of the English king when Prince Louis confiscated some of his lands—a move that Philip would have been wise to have prevented. In December 1213, Ferrand sailed to England and added his name to the growing roster of those determined to help John overthrow Philip. Henry, Duke of Brabant, a former ally of Philip, also joined the alliance, as did Hugh de Boves, an unsavory knight who had murdered a French official and eluded capture. In keeping with his uncle’s strategy, Otto agreed to lead the attack on Philip from the east.

Meanwhile, Philip continued his rampage through Flanders. When he heard that Ferrand had joined the alliance against him, Philip flew into a rage and redoubled his efforts to crush Flanders. One after another, the key towns of Flanders fell before the French monarch’s fury. By the summer of 1214, he had taken Tournai, Cassel, Lille, Bruges, and Ghent.

With Philip preoccupied reducing Flanders, John deemed it safe to launch a new campaign on the Continent. The English king landed at La Rochelle in Poitou on February 15, 1214. He was no more successful this time than he had been in the past. After nearly five months of campaigning, John had made little headway in France. When he learned that a small army led by Prince Louis was marching to relieve the siege of La Roche-aux-Moines in Anjou, John abruptly broke off the siege and fled to his base at La Rochelle. Thus ended John’s feeble attempt to regain his French inheritance on his own.

Otto Crosses into France

By 1214, Otto’s position in Germany had begun to deteriorate, not only because he remained excommunicated and in conflict with the church in Rome, but also because of his rivalry with Frederick Hohenstaufen. To continue as emperor, it was imperative that Otto defeat Philip in battle and restore his reputation in the eyes of western Europe. On the surface, the 39-year-old emperor seemed competent enough, but those like Innocent who bothered to scratch away his royal veneer found Otto to be shallow, undependable, and bungling, a shameless braggart whose deeds failed to match his overheated words.

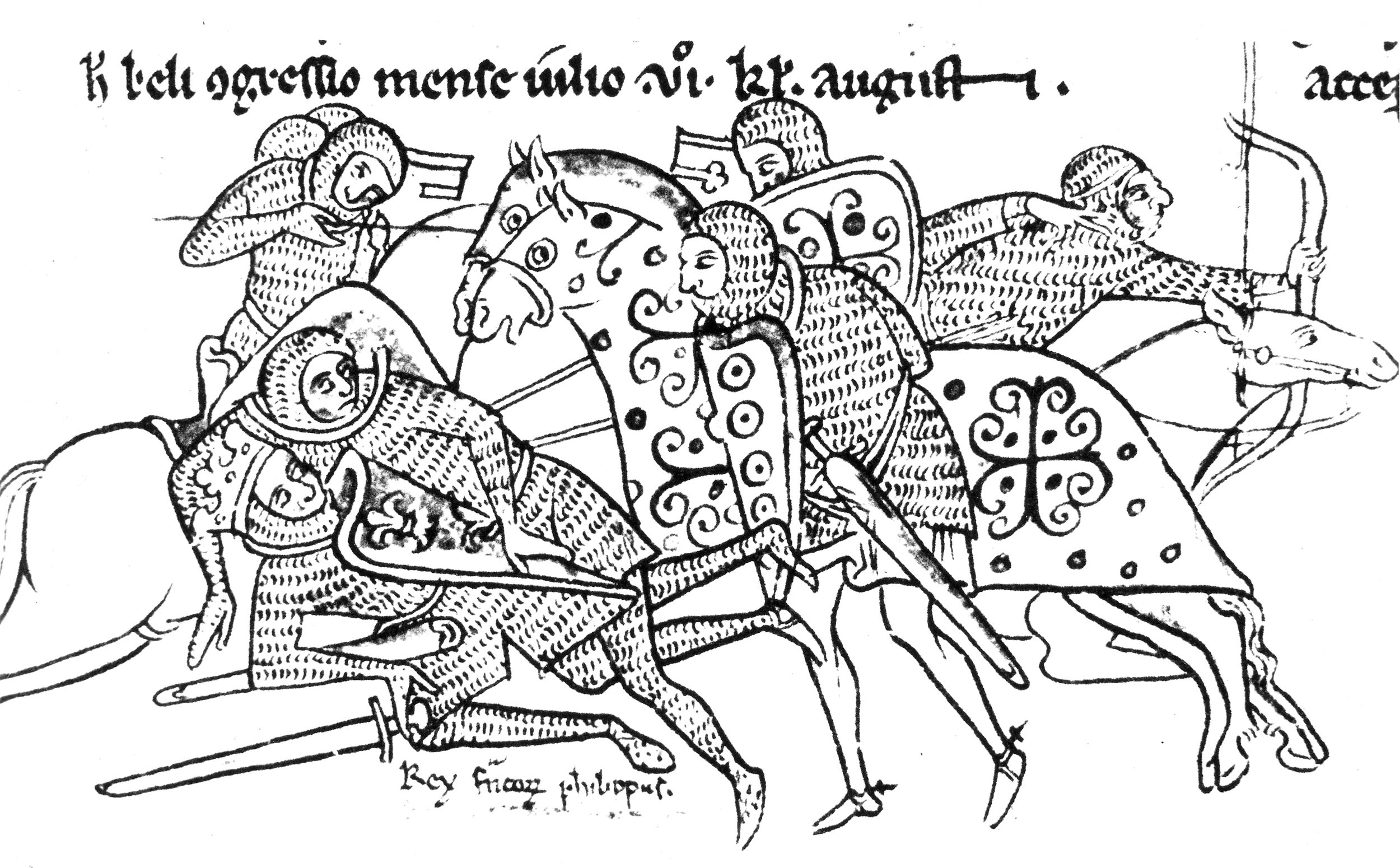

At Aachen, Otto began assembling the Imperial forces that would participate in the upcoming campaign against the French. Although his ultimate goal was to capture Paris, he would have to come to terms with Philip’s army in Flanders first. The core of Otto’s army consisted of scores of Saxon knights accompanied by large numbers of foot soldiers recruited from the Meuse and Rhine regions. Otto characteristically delayed attacking for several months, during which time he lost the vital element of surprise.

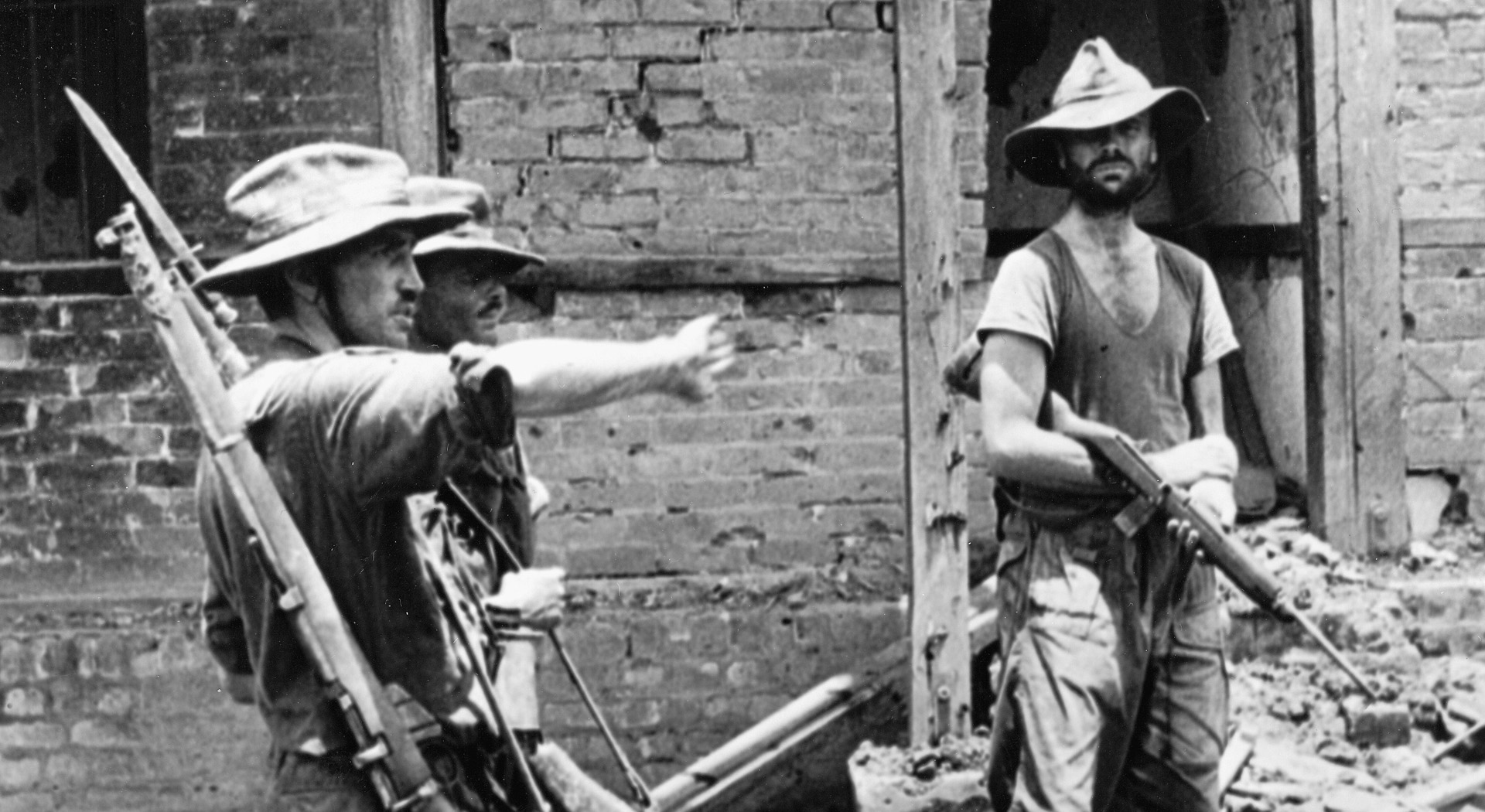

When summer came, Otto marched his army west to Maastricht and turned south to Nivelles, where he arrived on July 12. On the march, the emperor was accompanied by the dukes of Brabant and Limbourg. The Imperial army next entered the county of Hainaut, where it set up a large camp at Valenciennes to await allies. Shortly after Otto arrived in Hainaut, he was joined by the counts of Boulogne, Flanders, and Boves, and also by William, Earl of Salisbury. Salisbury, who was known as “Long Sword,” was the illegitimate son of Henry II and the half brother of King John. He was the oldest and most experienced leader among the allied commanders.

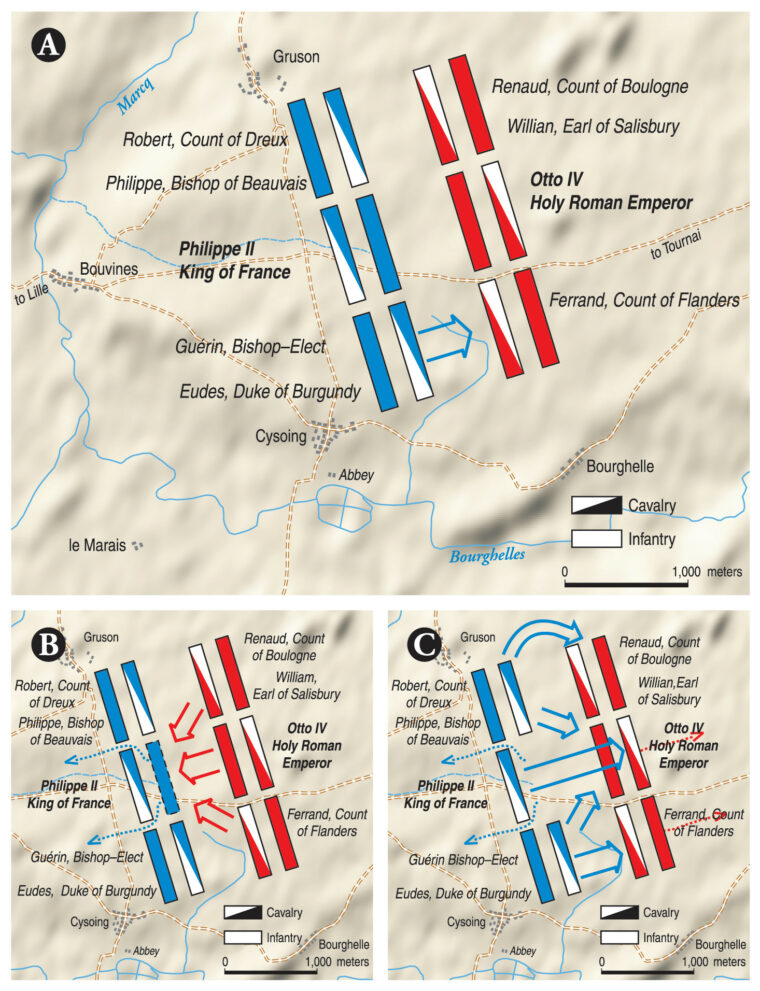

With Prince Louis still occupied fighting John in Poitou, Philip’s chief lieutenants were his cousins—Robert, Count of Dreux, and Pierre, Count of Auxerre—and Eudes, Duke of Burgundy. On par with Philip’s cousins and the duke were the bishop of Beauvais and the bishop-elect of Guerin. Wanting to place his army between the Imperial camp at Valenciennes and the English Channel, Philip marched north to Lille. There, he turned east, advancing along a raised Roman road through marshes that provided solid footing for his troops in the low-lying countryside. Arriving at Tournai on July 25, Philip easily brushed aside a small blocking force and occupied the town. At that point, he was resolved to give battle, but he was forced to backtrack toward Lille when his barons warned him that the roads in the area could not accommodate large bodies of men.

“I Know the French and Their Daring”

Meanwhile, Otto had shifted north to the castle at Mortagne. His scouts informed him on July 26 that Philip was falling back on Lille. With the French forces located at last, Otto resolved to attack at once. The majority of his commanders agreed with him, but one voiced dissent. “I know the French and their daring,” warned Renaud. “It would be rash to fight them in open country.” The count counseled patience and suggested waiting until the allied forces had improved communications among their various units before offering battle. Despite the warning, Otto remained determined to bring on an engagement. The following morning, his troops marched north from Mortagne, a route that virtually guaranteed that they would collide with the French.

Philip received news of Otto’s whereabouts through a message sent to him by an informant in the enemy camp. The message providing information on the enemy’s composition and movements came from Philip’s former ally, the Duke of Brabant, who despite signing on with the allies dreaded the wrath of the French king if they lost. On the morning of July 27, Philip’s army was strung out and heading west on the Roman road from Tournai to Lille. As he was approaching the bridge over the Marcq River at Bouvines, word came from his scouts that Otto’s vanguard was within striking distance of the rear guard and closing fast. To quicken the pace with which his forces could traverse the bridge, Philip had his pioneers strengthen the bridge to accommodate 12 men abreast and support heavily laden four-wheeled carts.

Guerin and the Viscount of Melun, protected by a small escort, had decided to ride behind Philip’s army as it marched toward Lille and watch for signs of the enemy’s approach. They did not have to wait long. The Imperialists forded a stream south of Tournai and made a feint as if they were planning to take the town, before turning west onto the Roman road and heading instead to Lille.

From a rise in the low-lying ground, the two men watched as the allied host drew ever closer. Guerin noted that the enemy horses were covered in protective armor, that the banners of various units were unfurled, and that foot soldiers were leading the host. To Guerin’s trained eye, all of these things were indications that the enemy was prepared to go straight into battle despite the Sabbath. Leaving Melun and a small band of lightly armed horsemen to continue monitoring the enemy’s progress, Guerin turned his horse around and rode hastily after the French army.

Like his enemy counterpart, the Holy Roman Emperor had also received fresh information from his scouts. One in particular insisted that the French were in full retreat and showed no inclination to stand and fight. But the Count of Boulogne, who knew Philip was too seasoned a commander to flee in the face of an adversary, suggested that the scout was wrong. Renaud again counseled Otto to avoid bringing on a general engagement until after the allied units had spent more time choreographing their movements. Waving off Renaud’s concerns, Otto decided to continue pursuing the French.

Philip may have been reluctant to do battle with the Imperialists because of the Sabbath, but Otto’s determination to fight left him little recourse. Although most of the surrounding countryside consisted of marshland dotted with dense willow thickets, the French king noted a level plain about a mile wide on the eastern bank of the Marcq that would afford the French cavalry sufficient room to maneuver. Never one to vacillate, Philip quickly resolved to make a stand and give Otto the battle he so clearly wanted.

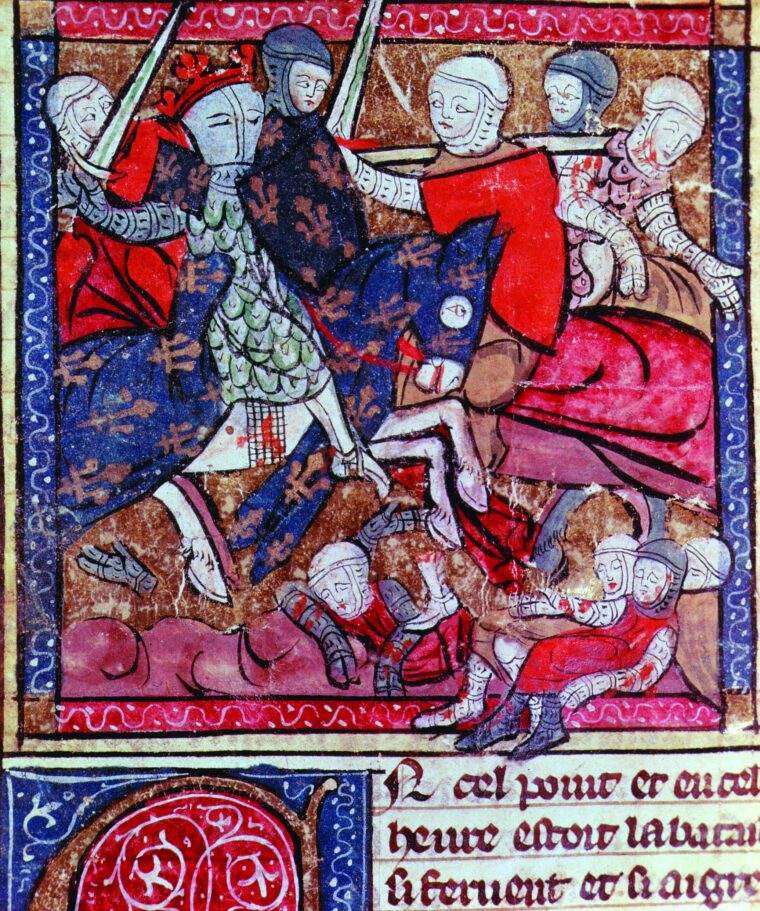

The French king said his prayers at a nearby chapel before donning his armor and mounting his horse. From there, he rode a short distance to meet with his barons. He warned all present to be true to him—unlike Renaud or Ferrand—or else suffer the consequences. “Protect me, and you will do well,” he said in a loud voice. “For with me, you will lose nothing. But double-cross me and I will pursue you wherever you may go.” At that point, according to the chronicler William of Breton, who was present at the meeting, a cry rose from the French host as the various troops moved to take up their battle positions: “To arms, barons! To arms!”

Bouvines

Otto had told his troops that his cavalry outnumbered the enemy three-to-one and that the French would not like the feel of cold steel. When the lead elements of the allied army led by Renaud and Ferrand caught up with the French rear guard in a wooded tract not far from Tournai, they fell upon it in a spirited attack. The French were forced to fend off half a dozen attacks before they reached Bouvines.

As the rear guard funneled up the Roman road toward Bouvines, Philip ordered the trumpets sounded to recall his vanguard from the west bank of the Marcq. These troops, fresh from several hours’ rest, immediately marched back across the bridge. With them they flourished the fabulous oriflamme banner of St. Denis, which featured a yellow sun set against a crimson background. The banner was brought from the church of St. Denis whenever the French king went into battle and the fate of his people was believed to be at stake.

Philip had the bridge dismantled after his vanguard marched across the river to prevent his troops from fleeing if they suffered a reverse on the battlefield. In this way, Philip demonstrated to his men that he intended the army to succeed or else be driven into the river and marshes and be destroyed. The decision to dismantle the bridge reflected the king’s faith not only in his abilities as a commander but also in the fortitude and competence of his troops.

Assembling on the Plain

The French fanned out onto the plain in either direction, parallel to the river. Philip rode to the center of the army, where he and his household knights took up positions in the second rank. Directly behind the king was a group of clergymen who chanted prayers beseeching the heavens for protection and victory. Placed in the king’s battalion to ensure his protection were some of the most distinguished knights of the realm, including William of Barres, Bartholomew of Roye, Gerard la Truie, and William of Garlande. Philip’s standard, on which golden fleurs-de-lis were cast against an azure background, was borne aloft by Galon of Montigny. The crack troops filed into position in front of Philip and his knights, who left gaps in their ranks through which the infantry could pass to the front. The foot soldiers had been recruited from the communes of Amiens, Arras, Beauvais, Compiegne, and Corbais. They were superbly outfitted and fought well together.

The rear guard, which filed into position on the right wing, was led by the Duke of Burgundy. Philip, who was concerned about the duke’s allegiance and wary that he might switch sides during the battle, ordered Guerin to assist Burgundy and ensure that he remained faithful to the king. Philip had no such concerns about the loyalty of those in whom he entrusted his left wing, his first cousins the Count of Dreux and the Bishop of Beauvais. On the two flanks the cavalry deployed in the front rank, with infantry in the second rank.

When the allied troops drew close to Bouvines, they spread out on both sides of the road to face the French. A large portion of the army was unable to reach the battlefield in time, and Otto probably fielded only 1,500 knights and 7,500 foot soldiers. Still, he had a slight edge over the French, who probably had about 1,300 knights and 6,000 infantry. Shortly before noon, Otto arrived to find the French making a bold stand with their backs against the Marcq. “Who ever told me the King of France was in flight?” he shouted in displeasure.

Otto took his place in the center opposite Philip. He was accompanied by the dukes of Brabant, Louvain, and Limbourg. Renaud commanded the allied right wing, while Ferrand took charge of the left. In the front rank of the cavalry on the allied right, Ferrand would fight with nobles from regions adjoining Flanders and a large unit of German cavalry. The allied deployments mirrored those of the French. The troops on the wings were formed into two ranks, with cavalry in the front rank, while the troops in the center had infantry in the front rank. After the enemy had finished deploying, Philip noticed that their right flank extended beyond the French left flank, and he ordered the French line extended to prevent his army from being outflanked.

Otto’s Army of Symbolism

As the French looked across the plain at their enemy, they saw that many of the enemy soldiers had sewn crosses onto their tunics. This reflected the belief of many in Otto’s army that they were fighting a crusade. An even more stunning sight greeted the French in the enemy center. From the second rank, Otto’s banner, depicting an eagle above a dragon with wings, swirled in the hot breeze. Instead of entrusting it to a single standard bearer, Otto had his banner transported into battle in a four-wheeled chariot meant to evoke the glory of ancient Rome.

Because of the Duke of Burgundy’s rather taciturn nature, it fell to Guerin to organize the French right wing for battle. The bishop-elect planned to attack the enemy opposite him before they had a chance to rest from their hard march. Following Philip’s instructions to watch closely for any duplicitous behavior on the part of the troops under his command, Guerin ordered a group of about 180 knights from Champagne, whose loyalty was suspect, to the back of the front rank. Before he gave the order to advance, the bishop-elect instructed the knights on the right wing to form a wide front so that they would all be able to participate in the action. After he finished his instructions, Guerin ordered forward 150 mounted sergeants from Soissons to soften up the enemy before unleashing his more heavily armed knights.

Seeing that the initial wave was composed of commoners, the Flemish knights across the field declined to charge the attackers, whom they disdained as their social inferiors, and simply lowered their lances to receive the attack. The Soissons cavalry might as well have charged a castle wall. A large number of the attackers’ horses were disemboweled by enemy lances, and the Flemish line was neither broken nor softened by the fruitless attack.

After the initial charge was shattered, three cocky Flemish knights rode forward and taunted their counterparts to engage them. A group of French knights in the front rank took up the challenge and rode forward to do battle. Two of the three Flemish knights were captured and a third, Eustache of Mechelen, managed to slip away to another location, from which point he shouted, “Death to the French!” In response, a group of French knights rode after him. When they had him surrounded, one grabbed his head while another reached over and slit his throat.

After the three rash Flemish knights had been eliminated, the French cavalry on the right wing rode forward en masse. More than 200 heavily armed knights charged across the field and collided with the Flemish, who had ridden out to receive them. In the swirling melee that followed, many riders on both sides toppled dead to the ground. Others had their mounts killed beneath them. One of these was the heavyset Duke of Burgundy, whose men dismounted and helped him to his feet. A fresh horse was brought forward and Burgundy was assisted into the saddle. Infuriated at being unhorsed, the duke fought furiously astride his new mount.

Several of the French knights on the right gained great renown in the fighting. The feats of the Count of St. Pol, in particular, helped sustain the morale of his fellow knights at the expense of Ferrand’s men. “He threw himself unto his enemies as fiercely as a hungry eagle throws himself unto a crowd of doves,” wrote the chronicler Breton. Hacking his way through to the rear of the Flemish ranks, St. Pol turned around and rode back, killing several more Flemish knights as he went.

Gradually, the Imperial left under Ferrand began to give ground, and large gaps opened up in their ranks. French attackers poured through. Several French knights managed to reach Ferrand and wound him repeatedly in mounted combat. Although the Flemish count fought fiercely, he was eventually unhorsed and captured. Upon seeing their leader captured and led away, the Flemish foot soldiers on the left flank lost their will to fight and abruptly fled the field.

Philip Charges on Otto

The battle in the center was not as one-sided as that on the southern end of the field. After passing through the infantry in the front rank, the Imperial cavalry thundered across the open ground toward the French infantry arrayed in front of Philip and his entourage. Although the French footmen in the front rank were experienced veterans, they were no match for some of the best cavalry in the empire. Many of the French infantrymen scattered in fear that they would be trampled by the enemy horsemen.

To check the enemy’s heavy cavalry, Philip’s household knights advanced, leaving the king with only a small bodyguard. As some of the most accomplished knights grappled with the enemy, a group of Imperial foot soldiers who had followed the cavalry charged the king’s position. Armed with long staffs that required two hands to use and had pointed tips capable of penetrating armor as well as a hook to unhorse riders, the soldiers repeatedly thrust their weapons at Philip in an effort to knock him off his horse. One of the soldiers managed to catch his hook in Philip’s chain mail and yank him from his saddle. The French king toppled to the ground with the weapon still embedded in his amor. Several enemy foot soldiers moved in quickly and struck the king, but their blows glanced off his sturdy armor.

Meanwhile, Galon of Montigny twirled the king’s standard overhead as a sign to French troops that the king was in desperate straits. Spotting the signal, several of Philip’s household knights swung their horses around and fought their way back to their sovereign’s side. One of them, Peter Tristan, leaped off his mount and got between the enemy soldiers and the fallen monarch. Others quickly arrived and threw themselves atop the king to deflect any additional attempts to stab him. Once the enemy had been beaten back, a fresh mount was brought to the king and he climbed back into the saddle.

Like the Duke of Burgundy, his brush with death seemed only to whet Philip’s thirst for battle. With the dust stirred by so many horses’ hooves reducing vision in some parts of the field to just a few yards, the king committed all the remaining cavalry in the French center to a counterattack. Despite surprisingly good coordination between the Imperial knights and foot soldiers in the center, fierce fighting by the flower of French chivalry and their veteran king gradually drove the Imperial troops backward across the field.

Through twirling clouds of dust, the French knights spied Otto astride a powerful steed. Clad in a gold tunic and clutching a gold shield with a black eagle emblazoned on it, the emperor became the primary target of the French knights as they dashed through the confused welter of men and horses. William de Barres, Gerard La Truie, and other French nobles managed to ride around the Imperial infantry and reach the emperor’s position. A sharp melee ensued as the French knights charged the emperor’s bodyguard.

La Truie swung his dagger in a wide arc at Otto’s chest, but the weapon merely glanced off the emperor’s armor. He swung a second time and sunk his blade deep into the head of Otto’s horse. With a loud scream, the horse broke free of the melee and rode a short distance before crashing to the ground. A group of four Imperial knights turned away from the fight and rode swiftly to the emperor’s rescue. One of them turned over his mount to Otto, and the shaken emperor rode swiftly away from the battle.

Rather than watch the destruction of his army, Otto began an eight-mile ride back to Valenciennes. De Barres gave chase, but several Imperial horsemen overtook him and stabbed his horse, putting an end to his pursuit. Meanwhile, French troops broke apart the chariot bearing the enemy standard and carried off the prize to Philip. The dukes of Brabant and Limbourg followed Otto’s lead and also fled the battlefield to avoid capture. When the French king learned that Otto had fled, he laughed heartily and said, “We will not see his face any more today!”

“Now You can Flee in Panic like the Rest of Them”

Although the French had triumphed on two-thirds of the field, fierce fighting continued on the French left. Convinced that Philip was disinclined to show mercy to him, Renaud was determined to fight as long as possible. Rather than try to flank the French to the north, Renaud and Salisbury ordered an oblique attack on the French center in an effort to overwhelm it. Seeing the enemy right wing strike for the French center, Dreux and Beauvais ordered their men forward to block the thrust.

Morale on the allied right was strong thanks to the mesmerizing presence of Renaud. A tall man who was well schooled in combat, he sat astride his horse in full armor, wearing a helmet with two black plumes that could be seen from afar by friend and foe alike. As the fighting ground on through the afternoon, he scolded De Boves for bringing on a battle that he was sure would end in defeat. “Here’s the battle you wanted, and which I didn’t,” he spat. “Now you can flee in panic like the rest of them. As for me, I shall continue fighting and be captured or killed.” Needing no further encouragement, De Boves rode away shamelessly from the battle.

Even though the French had the upper hand, it was well within the realm of possibility that Renaud and Salisbury might be able to capture the bridge over the Marcq. For this reason, the French could not claim victory until they had obliterated the allied right. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Beauvais ignored the ecclesiastical ban against men of the cloth shedding blood and plunged into the thickest part of the fighting. Swinging a mace that could punch a hole through armor, Beauvais fought his way to Salisbury’s position. Pulling up alongside the Englishman, the bishop swung a fearful blow that broke Salisbury’s helmet and sent him tumbling to the ground. As soon as he fell, the earl was captured and whisked to the rear by French infantry.

Facing an enemy with superior numbers, Renaud was forced onto the defensive. He ordered the 700 foot soldiers under his command to form two ranks and array themselves in a semicircle with their pikes thrust outward. The count and his knights used the semicircle as a field fortress, sallying forth repeatedly to strike the enemy. When they became winded, they simply withdrew inside the curtain of pikes. As the steamy afternoon dragged on, the fighting became a war of attrition. After many determined sorties, Renaud had no more than six knights left in the saddle.

Despite the odds, he continued to fight. On one of his sorties, a French infantryman named Pierre de la Tournelle managed to slip under Renaud’s horse and thrust his sword into its belly. The horse fell to the ground, pinning its master’s leg in the process. The French infantry swarmed over Renaud, ripping off his helmet and slashing his face. One of the men tried to stab him in the groin but failed. Guerin, seeing the commotion, rode over and dispersed the soldiers. Exhausted by long hours of combat, Renaud surrendered to the bishop-elect. While being dragged off to Philip, Renaud tried to escape but was subdued by foot soldiers intent on bringing in a man deemed an arch-traitor to the king.

The Battle’s Legacy: the Truce of Chinon and the Magna Carta

By sunset, Otto’s army was no more. Philip’s men gave pursuit, but the king called them back after they had gone only a mile. He wanted to keep his army together and to make sure that his prisoners did not escape in the commotion. Shortly after nightfall, Philip ordered trumpets sounded to recall his men to camp. Despite their weariness, the French stayed up deep into the night celebrating their triumph.

When the army returned in triumph to Paris, the population launched a weeklong celebration to honor the king and his army. The triumphant army brought with it 130 prisoners, among whom were five counts. Philip granted clemency to all the prisoners except Renaud and Ferrand, whom he deemed the worst sort of traitors. The prisoners were placed in the custody of various French nobles or imprisoned in Paris. All of those who received clemency eventually were freed after their ransom was paid. Ferrand remained in custody for 13 years before being released in 1227, a sick and broken man, after the deaths of Philip and Louis. Renaud, who was imprisoned for life, eventually committed suicide.

The reputation of both King John of England and Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV were irreparably tarnished by their defeat at Bouvines. A month after the battle, Philip marched with his army to western France to apply pressure to John’s allies in Poitou and Gascony. He eventually signed the Truce of Chinon in September 1214. The terms of the treaty, which were highly favorable to Philip, required John to pay 60,000 pounds in reparations to the French crown and to cede Anjou, Brittany, and Poitou to Philip as well. The next year, back in England, John was forced by his disgusted barons to sign the Magna Carta, the first real check on the heretofore “divine right of kings.” Otto, similarly disgraced, was soon deposed and died in exile.

After Bouvines, Philip held sway over northern France from the Bay of Biscay to the edge of the Holy Roman Empire and, most importantly, controlled the valuable wool trade in Flanders. The French king, who was henceforth called Philip Augustus for his achievement in battle, turned over command of the French military to his son, who upon his father’s death became King Louis VIII. As for Philip, he reigned for nine more years before passing away at the age of 58 in 1223.

Peace settled over France for a time. The rusting swords and spears that lay scattered in the fields surrounding Bouvines were ample proof that the French, under Philip, had demonstrated both the will and the ability to vanquish their foes. France had become a unified country instead of a mere royal possession.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments