By Gregory Peduto

Under the cover of the dusty Ethiopian night, the 17,000-man Italian Royal Expeditionary force scrambled over ragged hills and inactive volcanoes in the early morning hours of March 1, 1896. With less than four days’ worth of rations and even less water, the walrus-mustached commander of the Italian army, Oreste Baratieri, hoped to save his men from starvation by making an audacious surprise assault on the much larger enemy force arrayed against them.

In hushed whispers, nervous conscripts debated what lay ahead as they stumbled through the soupy darkness. The soldiers had overheard reports from the indigenous Ethiopian scouts after the renegade tribesmen returned from the front lines. The tales the indigeni told were not promising. They suggested that an unimaginable 100,000-man horde of Ethiopian defenders, assembled by Emperor Menelik II, was perched atop the Adwa Mountains somewhere in the distance. Despite their fears, the Italian troopers pushed on, knowing that they must reach their positions before daybreak.

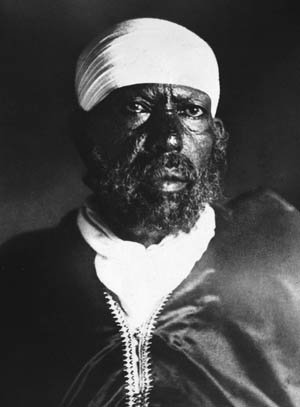

Emperor of Ethiopia, 1889-1910.

As dawn broke over the parched landscape, Ras (Prince) Alula stood like an unblinking sentinel while his Tirgrayan warriors snored around him. The exhausted commander’s face bore the wrinkles of time and the crusty white scars of battles long forgotten. Alula and his men were serving as frontline sentries while King Menelik and two-thirds of the Ethiopian army attended an Orthodox Christian mass at the nearby Church of Zion. After his nightlong vigil, Alula felt the warm blanket of sleep envelop him. He dreamed that he saw Italian units stumbling toward him under his rifle sights. It was no dream—the despised imperialists had finally arrived. Alula shouldered his Mauser rifle and let loose a warning shot. The crack of the rifle woke his men, and they joined the fray with a murderous volley of rifle fire.

As the opening skirmishes raged in the distance, Menelik, the owl-eyed emperor of Ethiopia, was thanking God for the vast army gathered on the foothills of the windswept mountains around Adwa. Comprising volunteers from every known Ethiopian tribe, Menelik’s warriors soon would pit their well-worn swords, spears, and rifles against crack Italian artillery in the greatest Afro-European battle since the defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama, two millennia earlier.

A trumpeting bugle shattered the king’s reverie. For lack of a better steed, Menelik leaped onto the back of a mule and led his tribesmen galloping to the front. Behind him, tens of thousands of warriors streamed down the crumbling rock face of the mountainside to meet the Italian invaders.

A Second Roman Empire

A latecomer to the European scramble for Africa, Italy did not thirst for empire until after its unification by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1871. After unification was complete, Italy’s first modern prime minister, Francesco Crispi, dreamed of building a second Roman Empire with colonies and protectorates all over the globe, but by then Africa had already been largely carved up by the other European powers. The few scraps left over were doled out by the 1885 Treaty of Berlin.

At the Berlin conference, the continental powers gifted Ethiopia to Italy—a cruel practical joke, considering that the African nation was home to an aroused populace long raised on the sour milk of war. Fierce Ethiopian tribesmen had successfully resisted a British expedition, smashed several Egyptian offensives, and crushed an onslaught of the Mahdi’s Islamic followers. In the absence of foreign invaders, the tribesmen battled one another in innumerable civil wars, blood feuds, and vendettas.

Manoel de Almeida, a Jesuit priest, praised the Ethiopians’ martial prowess. “In war they are reared as children,” he wrote. “In war they grow old, for the life of all who are not farmers is war.” The European superpowers clucked at Italy’s expense, but Crispi was determined to have his empire. Ethiopia’s strength even inspired the formidable Prussian, Otto von Bismarck, to caution: “Italy has a large appetite but poor teeth.” Crispi, to his credit, realized his country’s military deficit and set about honing Italy’s dull incisors into gleaming fangs.

As Crispi built a modern military, he dispatched Count Pietro Antonelli to the court of Menelik II, the strongest adversary of Ethiopia’s current emperor, Yohannes IV. From his northern stronghold of Mekele in Tigray, Yohannes ruled most of Ethiopia, while Menelik controlled the southern province of Showa. Antonelli immediately drove a wedge between the fractious relationship. Hoping to sway the balance of power within the divided country, the count entrenched himself in Menelik’s court with gifts of rifles and gold.

“Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah”

As a showdown with Yohannes loomed, an invasion of Sudanese Dervishes from the east in 1887 threatened Ethiopia’s security. Yohannes’s armies repulsed the invaders at Gallabat, but a stray bullet fatally knocked the king from his horse, and the Dervishes captured his body. Antonelli could scarcely believe his luck. It seemed as though Italy was about to conquer the ever-truculent African nation without having to fire a shot of its own.

The count promised to back Menelik in his bid for the throne in exchange for a formal diplomatic agreement. With Yohannes dead, Menelik, the self-proclaimed “Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah,” was crowned king of Ethiopia in 1889. Italian bureaucrats quickly drafted a treaty between the two nations that went down as one of the most duplicitous maneuvers in the history of foreign relations.

On the surface, the 1889 Treaty of Wuchale represented an even swap. The document stated that in exchange for the northern Ethiopian province of Baher-Mellash, the Italians would lend Menelik $400,000 in cash and a matching sum in the form of modern rifles. Even though the Ethiopian regent ceded a massive swath of his territory, the area was one he hardly controlled. Baher-Mellash, which the Italians renamed Eritrea, from the Latin marus erythraeum, or Red Sea, was the rebellious former stronghold of Yohannes.

The treaty contained a much more dangerous clause in the form of Article XVII. Crafted by Antonelli, Article XVII dealt specifically with the notion of Ethiopian sovereignty. The two translations of the agreement intentionally contained very different wordings. In the Amharic translation, Menelik retained independence; the document clearly stated, “The King of Kings of Ethiopia, may, if he so desires, avail himself of the Italian government for any negotiations he may enter into with other powers and governments.”

In the Italian version, however, the wording was quite different: “The King of Kings of Ethiopia, consents to avail himself of the government of his Majesty the King of Italy for all negotiations in affairs which he may have with other powers and governments.” The duplicitous discrepancies threatened the very autonomy of Ethiopia. If allowed to stand unedited, the document acquiesced to a protectorate status for the African country. Warily, the two nations signed the document.

Menelik’s Preparations for War

Menelik, who was no fool, secretly began planning for war. Armed with new Italian rifles, Ethiopian armies expanded eastward. Their forces plundered the Somali gold fields and raided nearby granaries. With the captured wheat, Menelik could keep his armies fed, and with the Somali gold he could arm them with the latest military hardware. Italy looked on with an unconcealed frown.

The conflict heated up, and the European nations chose sides. Whoever controlled the Horn of Africa controlled the Red Sea and the fate of the Suez Canal. For this reason, England and Germany sided with Italy and declared an arms embargo on the stubborn African kingdom. France and Russia backed Menelik. With the aid of French arms dealers based in the dusty outpost of Djibouti, Somalia, Menelik amassed a staggering cache of 80,000 rifles and 5,000,000 rounds of ammunition. The weapons included British Martinis, German Mausers, and American Winchester lever-action rifles.

More importantly, the French transported a number of quick-firing 37mm Hotchkiss cannons to the Ethiopian freedom fighters. A band of French artillery experts accompanied the guns. The Italian technological advantage rapidly evaporated in the face of foreign assistance. To make matters worse, the Hotchkiss cannons outranged the Italian 75mm Krupp mountain gun by more than 2,100 feet. If Crispi did not act quickly, Italian military superiority would be lost forever.

The Italians Build Their Presence

On February 28, 1892, Crispi appointed Italy’s greatest commander, General Oreste Baratieri, to govern Eritrea and its armed forces. A soldier since the age of 17, Baratieri was a member of Garibaldi’s legendary “Thousand.” The general found the Italian Africa Corps seriously deficient. Comprising mostly conscripts, the Italian units wore specially designed khaki uniforms and pith helmets and carried outdated M1870 single-shot rifles. No successful invasion was possible with these units, Baratieri warned, pleading with Crispi for an expanded budget and better soldiers.

The prime minister answered Baratieri’s pleas by dispatching Italy’s most elite forces and increasing the military budget by four million lira. The reinforcements consisted of five Bersaglieri sharpshooter battalions and one Alpini mountain battalion. The units were armed with the latest in small-arms equipment: the 1891 Carcano bolt-action 6.5mm rifle (later to become infamous as the alleged weapon of President John F. Kennedy’s alleged assassin). In addition to the infantry, two field batteries, two machine guns, and a mortar battery rounded out the reinforcements.

To augment the Italian forces, Baratieri raised four native African battalions, totaling 7,000 men. Known derisively as Bashi-Bazouks (mad heads), the African soldiers carried Turkish sabers and single-shot Remington rifles. By December 21, Baratieri’s men were primed for action. The general penetrated the Ethiopian border, while Colonel Giuseppe Arimondi stormed the northern Ethiopian city of Adigrat. As a reward for the successful operation, Arimondi was promoted to general.

The Italians go on the Offensive

Menelik could not tolerate the Italian encroachments on his territories. On February 12, 1893, the African monarch declared the Treaty of Wuchale null and void. The king’s courtiers then vaulted upon the quickest steeds in the kingdom and bolted outward to the four corners of Ethiopia and carried a call to arms to the rases, or feudal lords, of Ethiopia. Menelik’s message thundered: “An enemy is come across the sea. He has broken through our frontiers in order to destroy our motherland and our faith. He undermines our territories and our people like a mole. Enough! With the help of God, I will defend the inheritance of my forefathers.” It was a call the rases did not refuse. Even Menelik’s perpetual rivals, the lords of Tigray; Yohannes’s son, Ras Mengesh; and his loyal minister of war, Ras Alula, joined the confederation.

As Menelik’s armies gathered, the Italians went on the offensive. First, 7,500 men under Arimondi captured the city of Mekele. A month later, the Ethiopian city of Amba Alage fell to 1,800 soldiers led by Major Pietro Toselli. Despite the victories, the quickness with which Menelik’s forces assembled amazed the Italians. Menelik’s imperial bodyguard accounted for an impressive 30,000 soldiers, all armed with modern rifles, mail coats, light javelins, and curved swords known as shotels. Empress Taitu augmented the bodyguard with an additional 3,000 infantry and 6,000 horsemen of her own.

Over the next few months, Menelik’s capital city of Addis Ababa took on the appearance of a military camp as bristling soldiers descended on the town from the farthest reaches of his realm. From the desert wastes bordering Somalia, immense packs of camel-riding troops kicked up great plumes of dust on their way to the collection point. Ras Makonnen, the father of the future emperor Haile Selassie, marched into town at the head of 15,000 of his notorious Oromo swordsmen. The famed 10,000-strong Wello light cavalry, commanded by Ras Mikael, also turned up wearing their brightly colored quilted armor. Ethiopians revered the Wello cavalry for their unpredictable, lightning-fast assaults and their ability to melt back into the hinterlands. Even Menelik’s sworn Tigrayan enemies, Ras Mengesh Yohannes and Ras Alula, pledged their 21,000-man army to the cause. The force was unprecedented. Never before had an Ethiopian king united the provinces to do battle against a common foe; the result was a war party of 100,000 experienced fighting men primed for battle.

As Menelik awaited stragglers and prepared for full mobilization, he sent 30,000 warriors, led by Ras Makonnen, to the city of Mekele as a vanguard with the explicit orders not to engage the Italians. With so many mouths to feed, the African army could not afford to be bogged down in siege warfare. With that in mind, Makonnen’s force reached the Italian frontline fortifications at the city of Amba Alage on December 7, 1895.

A Hasty Assault on Amba Alage

Through his field glasses, Major Toselli, the senior officer at Amba Alage, scanned the horizon. It seemed as if the very hills had come alive. The situation appeared hopeless. The major’s men numbered only 2,300 inexperienced conscripts and indigeni, supported by a few artillery pieces. Toselli’s only chance lay in holding out until reinforcements arrived from Arimondi, who was posted at Mekele.

At the gates of the city, Makonnen called a council of war. In attendance were Ras Alula, Ras Mengesh Yohannes, Ras Wolle Betul, and several of their underlings. Makonnen’s orders were clear: the army was to avoid conflict and head north to Mekele. When the meeting adjourned, Kegnazmatch Tafesse and Fitawrari Tekle immediately disobeyed Makonnen’s guidelines. Seeking honor and plunder, the pair stormed the town with meager war parties that were easily repulsed by Italian artillery fire.

The unexpected assault put Makonnen in a difficult position. He could either disobey the king’s orders and attack or avoid the battle and be labeled a coward. In Ethiopia, cowardice was a far worse crime than disobedience, so Makonnen hatched a hasty assault plan. Alula was to take his 3,000 Tigrayan soldiers north and prepare an ambush on the road to Mekele for Arimondi’s expected reinforcements. The rest of the Ethiopian army then amassed for a frontal attack.

Toselli awoke at 6:30 am to the crack of gunfire and the roar of thousands of Ethiopians clawing up the city’s walls. As the battle raged, Toselli sent four artillery pieces to a hill overlooking the road to Mekele to cover his eventual retreat, but the cannons ran straight into Alula’s ambush and were destroyed. Moments later, Makonnen’s Oromo swordsmen vaulted the parapets and exchanged their rifles for gleaming swords.

While bloody hand-to-hand combat raged on the ramparts, a respite approached from the north. A trumpeting bugle heralded the arrival of Arimondi and his much-needed reinforcements. Italian cheers, however, were cut short by rifle fire from Alula’s detachment that beat back Arimondi and his men. The troops inside Amba Alage descended into panic, and many soldiers fled the city into the tips of Alula’s waiting spears. During the confusion, a bullet struck Toselli, killing him instantly.

Mekele Besieged

When Arimondi’s men limped back to Mekele, their appearance panicked the stronghold. Arimondi decided to take the majority of his troops to join the main Italian army at Adigrat. He left Major Giuseppi Galliano behind in the fortress to slow the Ethiopian advance. Italian engineers had spent the last four months fortifying the ancient adobe citadel, and it was ready for a protected siege. Barbed wire ringed the countryside to channel the Ethiopian forces into killing fields. Tribal scouts had booby-trapped the nearby mountains with explosives and boulders. Broken glass had been spread around the castle to cripple the barefoot Ethiopians. The highest point in the town, the Coptic Christian church of Enda Eyesus, commanded views of the entire battlefield, and Galliano converted the building into an artillery blockhouse. Preparations complete, the Italians settled in for a ferocious siege.

Makonnen and his warriors encircled Mekele on December 13, 1895, and obediently awaited the arrival of Menelik, but Makonnen’s indecision cost him. If he had captured the city’s water supply, the battle could have ended in as little as two weeks. Instead, he waited. On January 6, the date of the Ethiopian Christmas, Menelik and his army unlimbered their Hotchkiss cannons 2.7 miles from the city. The distance was some 1,800 feet beyond the range of the Italians’ 75mm guns.

The next day, Menelik’s Hotchkiss cannons opened up with a tactic taught to them by their French artillery instructors. This technique eschewed traditional mathematics-based gunnery and replaced it with a system of “walking fire” up to the Italian walls. When the first 37mm rounds struck Mekele, the defenders panicked. Galliano was outranged, outgunned, and seriously outmanned, but the Italian cannon fire repulsed the charging tribesmen.

A meeting of princes convened to discuss the stalemated situation. During the meeting, Menelik’s wife, Empress Taitu, recognized the importance of water in the campaign. Without water, no army could last in the scorching heat. Realizing this, Taitu led a detachment of her infantry to dam the city’s water supply, while Hotchkiss cannons pounded the adobe fortress to dust. The siege continued for two weeks, and the Italians resorted to breaking into stores of Communion wine to quench their thirst. Finally, on January 21, 1896, Galliano surrendered, and Menelik allowed the Italians to return to Adigrat unarmed.

Maneuvering for the Battle of Adwa

Menelik and his armies marched northward, bypassing the heavily fortified city of Adigrat, held by Baratieri and his 17,500-man expeditionary force. Baratieri had hoped to wait out Menelik’s advance, but a blistering letter from Crispi spurred him to action. In it, the prime minister complained: “This is a military phthisis, not a war, a waste of heroism, without any corresponding success.” Baratieri wanted the Ethiopians to lay siege to his unassailable citadel, but the tribesmen wisely avoided the town altogether and headed toward a pass through the Adwa Mountains into the heart of Italian-held Eritrea.

The race to Adwa was on. In their haste, Italian quartermasters packed rations for only 10 days. The oversight proved disastrous, but for the time being, the quick move bought Baratieri a superior position on Sauria, a hill just outside of Adwa. On February 14, Menelik’s army occupied the town of Adwa, 16 miles south of the Italian position. Once again, Baratieri tried to entice the tribal confederation to assail his entrenched position, but Menelik refused to budge. Running low on provisions, Baratieri planned to retreat and regroup across the Mereb River. With Crispi threatening to remove him, Baratieri’s career was on the line. Only a decisive victory over of the Ethiopian forces could clear his name. Therefore, he planned a nighttime surprise offensive to coincide with the Ethiopian holiday of Saint George’s Day on March 1. For the assault, the general split his army into five parties to occupy a line of three hills.

Major General Vittorio Dabormida, the leader of the right column, was ordered to seize the Spur of Belah and the Hill of Belah with a force of 3,800 troopers. His units consisted of the 2nd Infantry Brigade, the 2nd Battery Brigade, and a battalion of mobile militia. In addition to his infantry, Dabormida had at his disposal several artillery pieces of the 5th, 6th and 7th batteries.

Baratieri ordered the central column, under Arimondi, to capture Mount Belah. Arimondi’s detachment included the 1st Infantry Brigade, the 5th Indigeni Battalion, one regiment of Bersaglieri sharpshooters, and the 11th and 8th Batteries, a force of 2,439 soldiers, and 12 artillery pieces. General Matteo Albertone’s column protected the army’s left flank from a mountain range incorrectly labeled on his map as the Kidane Meret. At his disposal were four indigeni battalions and the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Batteries, totaling an additional 4,076 soldiers and 12 cannons.

Just behind the ridgeline, General Giuseppe Ellena’s force provided a reserve of 4,150 men. His units consisted of the 3rd Infantry Brigade, an Alpini battalion, the 3rd Indigeni Battalion, two quick-firing cannons, and a company of engineers. Rounding out the forces, Baratieri’s own mobile command had over 5,000 troops, including two Alpini companies. Italian command left the two machine guns behind because sand had rendered them inoperable.

At 9 pm, Baratieri and his men stalked into the Ethiopian night. It was imperative that they reach the safety of the hills by dawn. Around 5 am, Dabormida’s right column captured its objective without a fight. Fifteen minutes later, Arimondi and the Italian center moved into position while Ellena’s reserve secured the rear. Albertone’s incorrect map led the left flank four miles off course to a mountain occupied by Ras Alula’s Tigray vanguard. At 6 am, Albertone realized his mistake when a murderous volley of gunfire tore through his ranks. A wild bayonet charge led by Colonel Domenico Turitto and the 1st Indigeni Battalion drove Alula from the hill, but Albertone’s men were still miles away from their true objective.

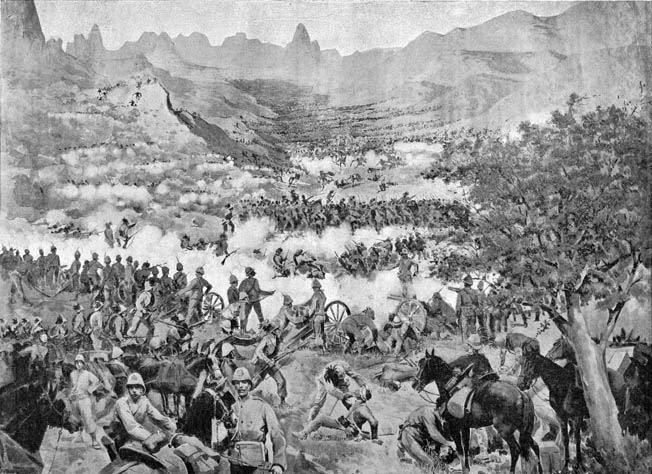

Alula dispatched messengers to invite other Ethiopian warlords to the melee. First to join the bloody fray were Ras Mikael and his majestic Wello cavalry. Next, Ras Makonnen’s Ormo swordsmen streamed into the clash. Finally, a messenger reached Menelik, who had gathered the entire Ethiopian army.

Working in tandem, Alula, Mikael, and Makonnen employed an old Ethiopian technique of mountain warfare called afena. A sort of barefoot blitzkrieg, afena involved encircling an enemy while artillery pounded them into submission. Under covering fire, the warriors advanced toward the center with the goal of engaging their foes in hand-to-hand combat. As the tribesmen enveloped Albertone, his artillery cut bloody swaths through the charging Ethiopian formations. Dejazmach Balcha Abba Nefo brought up the quick-firing Hotchkiss cannons and decimated Albertone’s guns.

A Brief Battle

In the early morning hours, the faint pop of rifle fire from the left flank carried to Baratieri’s ears. It was too dark to observe the battlefield, but the general assumed that the noise emanated from simple skirmishes rather than an epic struggle. At 6:30 am, Baratieri scaled the heights of Mt. Raio and scanned the hills with his telescope. He did not like what he saw—Albertone’s brigades were missing. Baratieri dispatched messengers to locate the left column, but they never returned. It was ominous.

At 6:45, Baratieri drafted a vague order for Dabormida’s right column to “join hands” with Albertone. Based on the cryptic message, Dabormida moved his entire force to the southeast, but Baratieri intended for him to send only a few units to locate Albertone. This disastrous miscommunication was the undoing of the entire Italian army. Dabormida packed up his column and wandered into a labyrinth of ravines, leaving the right flank completely exposed. Within an hour the major general was hopelessly lost.

Around 7 am, the onslaught on Albertone’s left built to a fevered pitch. Empress Taitu galloped to the scene and directed the offensive. Wave after wave of hacking and slashing warriors leapt upon the Italians from every rock, tree, and blade of grass. As the swordsmen charged, deadly accurate Ethiopian rifle fire rained down upon Albertone’s brigades. Augustus Wylde, a noted war correspondent, later opined: “The Abyssinians are as good shots as any men in Africa, the Transvaal Boers not excepted.” First to fall to the relentless swarm was Colonel Turitto and virtually the entire 1st Indigeni Battalion.

By 7:30 am, Albertone drafted an imperative message to Baratieri, telling him that his forces could not maintain their positions past 8:15. Baratieri, however, did not receive this notice for another 45 minutes. By then, the message was not needed. A stream of fugitives running away from Menelik’s personal 30,000-man Showan bodyguard announced the destruction of the Italian left flank.

In response to the Showan blitz, the center column’s 8th Battery opened fire on Albertone’s retreating forces in order to check the advances of Menelik’s rampaging bodyguard. Shells blasted Ethiopian and Italian alike. In response to the barrage, the warriors formed a crescent formation and seized the Spur of Belah, cutting off all communication with Dabormida’s lost right flank. Two companies of Bersaglieri sharpshooters under Colonel Lorenzo Compaino stormed the hill. With bayonets and rifle butts, the Bersaglieri collided with 10,000 Showans and recaptured the heights at a great cost. A bullet zipped though Compaino’s leg, and he was last seen with his “knee on the ground defending himself heroically with his sword until a blow with a lance laid him low.” Only 40 sharpshooters survived the hillside encounter.

A reserve battalion was dispatched to relieve the Bersaglieri. Baratieri then ordered Ellena to bring up two quick-firing guns from the rear to support the center. The hero of Mekele, Major Galliano, deployed on Mt. Raio and defended the left flank with his 1,200 indigeni soldiers. At 10:30 am, Albertone ordered his beleaguered left flank to retreat. To stem the advancing torrent, the general remained behind with a handful of soldiers to protect his fleeing men. Moments latter, a bullet knocked Albertone from his horse and the left flank crumbled, releasing the whole Ethiopian horde upon the Italian force. Galliano and his indigeni were cut to pieces by Makonnen’s Oromo swordsmen.

The Tigrayan armies of Alula and Mengesh Yohannes joined Menelik’s bodyguard and slammed into Arimondi’s center column. Italian 75mm cannons pounded the sea of warriors until they ran out of shells. Sensing victory, the Ethiopians cast down their rifles and dove headlong into Arimondi’s brigades with sabers flashing. Baratieri flung the last of his reserves into the maelstrom. The 16th Battalion and two companies of Alpini infantry advanced to support the center, but it was to no avail. The center broke and ran after a pack of Oromo warriors who fatally stabbed Arimondi.

The Italians Retreat

At 11 am, Baratieri ordered a retreat. Unable to contact Dabormida, the general was forced leave him to battle Menelik alone. Dabormida’s lost detachment centered its defenses on a hill with a huge sycamore tree. Beneath the tree, Dabormida massed his artillery. Colonel Cesare Airaghi occupied the nearby Mariam Shewito Valley with a party of infantry. A rear guard led by Colonel Luigi De Amicis protected the nonexistent communication lines with the Italian main force.

The onslaught began when a party of over 20,000 horsemen overran Dabormida’s rear guard and then headed straight for the general’s main brigades. In the first 12 minutes of the battle, all but two of his 14 officers were trampled underfoot. Dabormida died rallying his exhausted men around the broken trunk of the sycamore tree at the center of his position. With remarkable suddenness, the Battle of Adwa was over.

Two days later, the scattered remnants of Baratieri’s once-proud army limped into Eritrea, their welcome home nonexistent. Baratieri, Italy’s greatest commander, returned to Rome to face court-martial proceedings. Crispi retired from politics in disgrace, and Rome sued for peace with Ethiopia and tore up the disputed Treaty of Wuchale.

On one fateful day, a band of African freedom fighters checked the tide of European imperialism. Over 70 percent of the Italian army was destroyed by Menelik’s monumental confederation. Casualties included 7,500 dead Italians, 7,100 slain Eritreans, 1,428 wounded, and 1,865 prisoners. Ethiopian casualties were also appallingly high—some 7,000 dead and 10,000 wounded. For years to come, the Battle of Adwa weighed heavily on the Italian national psyche, an ever-smarting wound that would induce Benito Mussolini to occupy Ethiopia in 1935—a doleful prelude to the fast-approaching cataclysm of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments