By Mike Phifer

The two Indian scouts ignored the gawking soldiers as they rode into where the bluecoated troops had bivouacked for the night at Mule Springs in the Texas Panhandle on November 24, 1864. They headed straight for Colonel Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson, commander of the expedition, to report what they had found. Ten miles to the east the scouts had cut the trail of a large group of Indians driving cattle and horses. Nearby Carson had 400 men, including New Mexico and California volunteer infantry and cavalry and Ute and Jicarilla Apache scouts. He also had two mountain howitzers, 27 supply wagons, and an ambulance. His mission was to defeat the hostile Comanche and Kiowa.

With word that hostile Indians were in the vicinity, Carson ordered his cavalrymen to mount up. Leaving the infantry to guard the wagons at Mule Springs and then follow in the morning, Carson’s force moved out just before dark. The men were on strict orders not to talk or smoke. By midnight they had found the fresh trail of the band of Indians they were pursuing. Carson ordered a halt, preferring to wait for daylight before pushing any farther into hostile country.

When the first streaks of dawn finally appeared in the eastern sky, Kit Carson and his men rode out again. The Ute and Jicarilla scouts quickly discovered three enemy pickets. After discarding their buffalo robes, the scouts galloped after the fleeing pickets. Carson ordered most of his cavalry after the scouts, knowing that a Comanche or Kiowa village could not be far away.

Carson followed along with a small detachment of cavalry acting as escorts for the slower moving howitzers. Just ahead the cavalry and scouts attacked a Kiowa village of 200 lodges. The Kiowa warriors retreated downriver followed by Carson’s men. Unbeknownst to the bluecoats, the Kiowa women and children, along with a white captive woman and two children, were hiding in the foothills nearby.

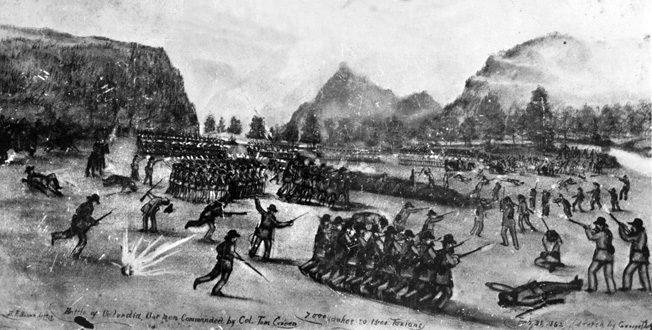

When Carson caught up with the bulk of his men they were at Adobe Walls, a trading post that had been established in the mid-1840s but was now abandoned. The cavalrymen had corralled their mounts in the stout ruins of Adobe Walls and then spread out as skirmishers. About 200 Comanche and Kiowa were galloping back and forth in front of the skirmishers. They shouted at the bluecoats and fired at them from underneath the necks of their horses. More than 1,000 Comanche and Kiowa warriors were spotted moving forward.

a trapper exploring the American West and gaining valuable knowledge of the land and the native peoples.

On Carson’s orders the howitzers fired on the Indians, sending them on a dead run for a Comanche village of 500 lodges that lay a mile away. Carson, believing the fight was over, ordered his men to eat something and water their horses before pushing on to destroy the Comanche village.

In less than half an hour the Comanche and Kiowa had returned. They were determined to fight. Kit Carson and his men were in for the fight of their lives. Fortunately, they had a seasoned frontiersman leading them. If anybody could get them out of their predicament, it was Carson.

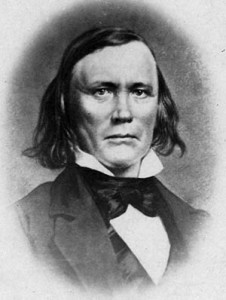

Kit’s Beginnings

Born on December 24, 1809, in Richmond, Kentucky, Kit Carson was raised in Missouri, where his family moved in 1811. Carson, who received his nickname from his family, grew up under the threat of Indian raids and did not get much schooling. He was unable to read or write but was good at learning languages. In addition to his native English, he also spoke Spanish and a number of Indian languages.

After his father died and his mother remarried, Carson became increasingly rebellious. At 16, Carson’s mother apprenticed him to a saddle maker in Franklin, Missouri. Carson stuck it out for two years and then abruptly left his apprenticeship in August 1826. He landed a job working in a caravan headed for Santa Fe.

In the following years, Carson worked as a trapper exploring much of the American West gaining valuable knowledge of the land and the natives, having lived with them and fought with and against them. In 1842, Carson’s life was to change when he met Lieutenant John Charles Fremont of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Carson joined Fremont, the “Great Pathfinder,” as a guide in three of his Western expeditions. In Carson’s last expedition with Fremont, they crossed the Sierra Nevada Mountains during the winter to arrive in California, then part of Mexico. Carson, by Fremont’s side, served with distinction in California during the Mexican War.

Fremont, brevetted with the rank of major, made Carson a lieutenant during the war. On September 5, 1846, Carson rode out of Los Angeles with a small group of men intending to carry a dispatch across the continent to Washington. A month later near Socorro, New Mexico, they ran into Brig. Gen. Stephen Kearny’s Army of the West, which had been sent to capture New Mexico and California. Much to his chagrin, Carson was ordered to give the dispatch to another scout and guide the army back to California. Believing California was under American control, Kearny took only 121 dragoons and two mountain howitzers, sending the rest of his men back to Santa Fe.

Upon reaching California, Kearny was soon to learn that it was in rebellion again. Joined by a small force of men, Kearny pushed on toward San Diego. Before he reached it, though, Kearny’s men soon found themselves engaged with enemy lancers at San Pasqual on December 6. Carson was dismounted during the fight and almost got trampled, but he survived unscathed, which could not be said for Kearny and many of his men. The battered troops slowly pushed on the next day while being harassed by the enemy. Thirty miles from San Diego, Kearny’s men entrenched on a hill and sent three men forward for help. Kit Carson was one of three men who slipped out in the darkness. All three men made it to San Diego, and reinforcements were ordered out to help Kearny.

Carson carried dispatches to Washington in 1847, where he met with President James Polk. The president commissioned Carson a second lieutenant in the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen and ordered him to carry dispatches back across the continent. Carson’s early military career would be brief because the Senate refused to confirm the appointment.

A National Hero

The soft-spoken, diminutive frontiersman was soon to become a national hero when Fremont wrote glowingly of him in his widely published reports of his expeditions. It would not be long before so-called blood and thunder novels were being penned about Kit Carson’s hair-raising, bloodthirsty fictional exploits.

After his first brief military service, Carson returned to his home and his young wife to take up farming and ranching in New Mexico. In early 1854, Carson was appointed as Indian Agent for the Ute tribe. He would hold this position for seven years until the start of the American Civil War. On May 24, 1861, Carson resigned his position and a month later was commissioned a lieutenant colonel, becoming second in command in the 1st Regiment of New Mexico Volunteers. When its aged commander, Colonel Ceran St. Vrain, resigned, Carson took charge of the outfit and was promoted to full colonel in October.

During the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, Kit Carson led his men into action at the Battle of Valverde on February 21, 1862, along the Rio Grande. Although inexperienced, Carson’s New Mexicans proved capable soldiers. At Carson’s suggestion his troops were posted on the west side of the Rio Grande, allowing his men to watch the battle raging on the east side to steady themselves. Carson and his New Mexicans soon entered the bloody fray when they were ordered to cross the river and join in on an assault on the Confederates. The Rebels launched a two-pronged counterattack. Carson proved to be a steady leader pacing up and down the line calling out to his men, “Firme, muchachos, firme!” Carson’s New Mexicans beat back the Confederates attacking them and considered the battle won. They were shocked and surprised when they heard the bugle call to retreat. The Rebel attack on the Union left had done much better, capturing some Federal guns and driving off the troops defending them. Following orders, Carson and his men forded the Rio Grande and retreated with the rest of the Union forces.

The Confederate advance into New Mexico was stopped at Glorieta Pass in late March 1862, and the Rebels were soon retreating to Texas. The Federal troops in the territory then turned their attention to dealing with raiding Mescalero Apaches, Navajos, Comanches, and Kiowas, in which Kit Carson was to play a pivotal role. By this time Carson commanded the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Cavalry Carson was ordered by Brig. Gen. James Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico, in late September to reopen Fort Stanton, which had been abandoned during the Confederate invasion. Fort Stanton was to serve as a base from which Carson could pursue the Mescalero Apaches. “There is to be no council with the Indians nor any talks,” said Carleton. “The men are to be slain whenever and wherever they can be found. The women and children may be taken as prisoners, but, of course, they are not to be killed.” Carleton informed Carson that if the Indians begged for peace, then their chief and 20 of their principal men were to go to Santa Fe, while Carson was to continue to hunt down Apaches.

Carson did not like the order, thinking it too harsh as he had been friends at one time with the Mescalero Apaches. Carson argued for more humane treatment of them, knowing that they were poorly armed and had been driven to areas where there was little game. Carleton would have none of it. He wanted them hunted down and killed. Carson followed his orders and led his men after the Mescaleros.

It was a quick war with Carson leading his men from Fort Stanton, while two other detachments of troops moved against the Mescalero Apaches from Mesilla and Franklin. By the end of the year, Carson was looking after a large number of starving natives at Fort Stanton.

Scorched Earth

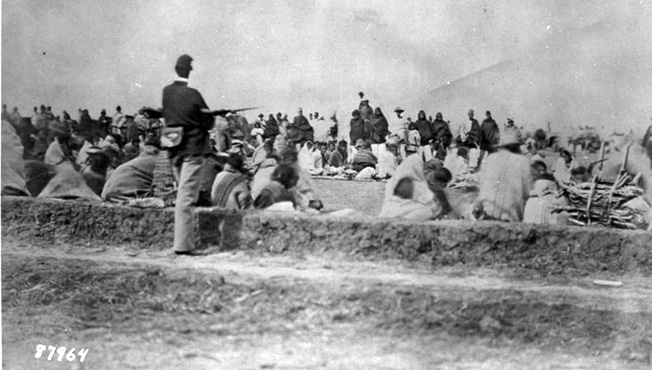

Afterward, Kit Carleton turned his attention to the Navajos. Carleton had made peace offers to the Navajos that required them to go to the reservation at Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico to learn to support themselves by farming. He gave them until July 20, 1863, to go in or they would be considered hostile. Not surprisingly, they rejected the offer. Carson would soon find himself back in the saddle campaigning against the Navajos; however, he was not keen on warring with them. By that time, Carson was in poor health. He had tried to resign from the army as early as February 1863, but Carleton had refused his resignation.

It was a brutal scorched-earth campaign that continued into the winter of 1863-1864. Carson would take his men right into Canyon de Chelly, the stronghold of the Navajo. On January 9, 1864, Carson led his men to the western end of a red rock, steep-cliffed canyon, while Captain Albert Pfeiffer with two companies of troops pushed through from the eastern end of the canyon. Three days later Pfieffer joined up with Carson, having met minimal resistance and captured 19 starving women and children. The next day 60 starving Navajos surrendered to Carson. Thousands more would follow. By mid-March, 6,000 Navajos had surrendered with the number eventually increasing to 8,000. In the Navajos 400-mile long walk to Bosque Redondo, many would die from starvation, disease, and exposure.

A Battle of Desperation

After a short stint in command at Fort Sumner overseeing the Bosque Redondo reservation, Kit Carson again attempted to resign. Carleton again rejected the offer, instead sending him to chastise the Comanches and Kiowas who had been causing havoc on the Santa Fe Trail during the summer of 1864, attacking emigrant trains and army caravans. The attacks were so bad that the army’s supply line and mail were nearly cut. Carleton ordered Carson to punish the Indians before the onset of winter. Setting out on November 12, Carson would a little over two weeks later find himself in a desperate situation at Adobe Walls.

The Comanche and Kiowa warriors returned to Adobe Walls, being careful not to bunch up and offer themselves as targets to Carson’s two howitzers. Instead, many of them dismounted and, using the tall grass as cover, skirmished with the bluecoats, while the majority of them charged across the troopers’ front firing from under the necks of their horses. Carson urged his men to stay calm and direct their fire at the waves of warriors attacking them.

It was soon becoming painfully clear that Carson and his men had bitten off more than they could handle. They estimated the warriors they were now facing numbered about 3,000. Parties of warriors were spotted a couple of miles away, heading for the Kiowa village the bluecoats had earlier passed to get horses and see to the safety of their women and children.

Carson now began to fear for the safety of his supply wagons and 75 foot soldiers left to escort them. At 3:30 pm, he ordered the horses to be brought out in preparation for a retreat despite the protests of many of his officers who wanted to push on to the big Comanche village. With years of experience in Indian warfare under his belt, Carson knew it was time to get his men out.

While one trooper in four led the horses, the other bluecoats spread out as skirmishers on the flanks to protect the retreating column. The crews of the two howitzers, meanwhile, brought up the rear, blasting away at the pressing warriors who increased their attacks.

“Indians charged so repeatedly and with such desperation that for some time I had serious doubts for the safety of my rear,” wrote Carson. To make matters worse, the Comanches and Kiowas lit a grass fire that swept toward the retreating column. Using the smoke as cover, some warriors got close to the column and fired into it before being discovered. To avoid the fire, Carson and his men had to climb the bluffs of the river valley. There they could better see the situation that faced them

By sundown Kit Carson and his men had reached the Kiowa village, which they found full of Indians attempting to save their possessions. After the mountain howitzers fired a couple of shells into the village, the troopers charged. They plundered the lodges of buffalo robes and even found some white women’s clothing. They then set fire to 160 lodges and some equipment the Indians had captured earlier. The two guns, which were repositioned on a 20-foot hill, continued to bang away. Each time they were fired, the recoil sent them down the hill, where they would have to be manhandled back up again. One last parting shot from the gun into a group of 30 or 40 retreating warriors from the southern part of the village ended the battle.

The Scout Resigns

By nightfall Carson and his command, exhausted from 30 hours of fighting, reached their supply wagons and escort, which were still safe. Despite the ferocity of the battle, Carson’s casualties were remarkably light, with two troopers and an Indian scout killed and as 25 wounded. Three of these would succumb to their wounds. Casualties could have been much worse, and an officer serving with Carson believed the two mountain howitzers had kept the command from being wiped out. But Carson’s coolness and sound judgment also played a significant role in their survival. The Comanches and Kiowas, Carson estimated, suffered 60 killed and wounded, although their losses may have been considerably greater.

Carleton called Kit Carson’s battle at Adobe Walls “a brilliant victory.” Carson admitted four years later that the Indians had defeated him. But Carson’s foray showed the Comanches and Kiowas that they were not safe from attack even deep in their own territory. Carson was brevetted a brigadier general in March 1866, but his health rapidly deteriorated. He resigned from the U.S. Army the following year. The legendary soldier and scout died at the age of 58 on May 23, 1868, in Fort Lyon, Colorado.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments