By Eric Niderost

The Armada campaign marked the beginning of a new age in naval warfare. Before this time, naval encounters were essentially land battles fought at sea. Ships were designed to close with an enemy, then grapple as soon as was feasible. Once the two vessels were locked in a deadly embrace, soldiers would fight it out until one side or the other was vanquished. In this style of warfare, sailors were mere transporters whose main mission was to carry soldiers close enough to carry on the fight. Seamanship was secondary, and tactics were straightforward if not crude.

[text_ad]

The galley had dominated Mediterranean waters since the age of the Greeks, and it was natural for Spain, as a leading power in the region, to maintain a force of them. A typical galley was long and sleek, a thing of beauty to those who beheld it from afar. But it was propelled by oars, with muscle provided by galley slaves, and these whip-driven wretches were a poor substitute for a regular complement of masts and sails. Low in the water, the galley’s shallow draft performed poorly in the rougher, storm-tossed Atlantic waters.

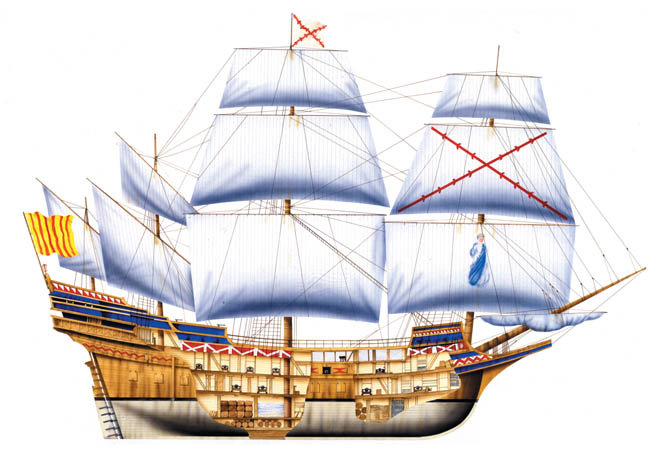

The Spanish gradually abandoned the galley, putting their faith in treasure-fleet galleons. The galleons were magnificent if cumbersome engines of war, displacing from 250 to 1,000 tons apiece and carrying up to 50 guns. They were literally floating fortresses, with high forecastles and sterns crowded with soldiers in times of battle. The galleons did sport some powerful guns, but the Spanish were still wedded to the close-and-grapple form of naval warfare.

By the last half of the 16th century, English shipwrights were experimenting with a whole new concept of ship design. John Hawkins, one of England’s leading sea dogs, is usually given credit for being the catalyst for these changes. When Queen Elizabeth I appointed him Treasurer of the Navy in the 1570s, Hawkins set to work implementing his ideas. It was during this period that the so-called “race- built” ship, or English galleon, was born. The English galleon was lower and sleeker than its Spanish counterpart, with lower sterns and forecastles. The lower profile lessened wind resistance and made the ships much more maneuverable.

The new design also provided more stability for artillery of various kinds, making the galleon a gun platform. Under this concept, a race-built ship would pound the enemy from afar, its maneuverability enabling it to stay safely way from the enemy’s lethal grappling hooks. Although there would still be boarding on occasion, naval warfare essentially would become long-range artillery duels.

Revenge was a typical race-built galleon, and the favorite ship of Sir Francis Drake. Built in 1574, she was a two-deck ship of about 500 tons. Revenge boasted four masts, and was so fast and maneuverable it was counted as one of the queen’s finest vessels.

For all its innovations, the English galleon shared some defects common in the 16th century. Most of these ships carried an excessive variety of ordnance, and Revenge was no exception. Her main battery of 18-pounder cannons was supplemented by culverins, and probably falcons, minions, and small bronze pivot guns. In long, protracted fights, it was difficult to keep ships supplied with such a bewildering variety of shot. Once a certain type of shot ran out, those particular guns fell silent. It must have been frustrating for ever-aggressive sailors such as Drake.

By 1588, even the Spanish were starting to learn these new concepts of war, although they still clung stubbornly to their old ways of battle. Although it didn’t affect the outcome, some effort was made to supply the Armada with longer range culverins. This is mute testimony that King Philip II was starting to copy, however tentatively, English methods of war on the high seas. In his case, it would prove too little, too late.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments