By Kirk Freeman

Big battles make the history books. But for the soldiers, it was often the smaller, fiercer fights they remembered most keenly later in their lives.

On May 16, 1863 the Battle of Champion’s Hill raged east of Vicksburg, Mississippi. It ended in a Confederate defeat and subsequent retreat that same evening to the previously erected earthwork fortifications at Big Black River. It was here on May 17, 1863 that one small brigade comprising the 21st, 22nd and 23rd Iowa and 11th Wisconsin made for themselves a brief but fiery moment in history that they would remember as their pinnacle in the war.

May 16 was a miserable day for the worn and worried man who rode his horse past the butternut pickets who guarded the fortifications along the Big Black River, just a few miles outside Vicksburg. Confederate General John C. Pemberton, commander of the Vicksburg defenses, had reluctantly left these formidable entrenchments around Big Black River, to strike what he had hoped was Ulysses S. Grant’s rear. That was days ago, and tonight he and his army were returning in defeat.

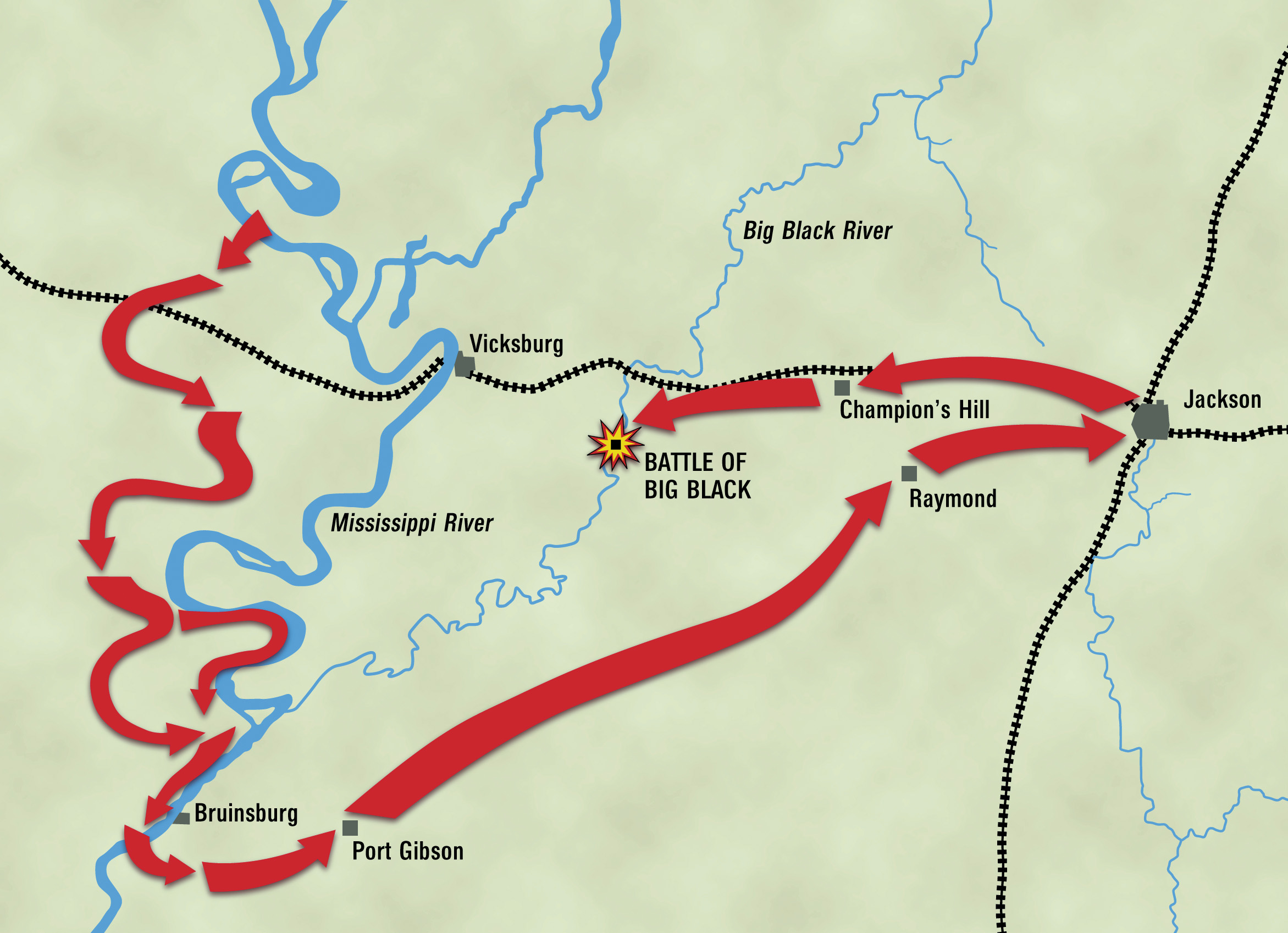

Since the beginning of May, the Confederate garrison at Vicksburg had received reports that Grant’s Federal Army was on the eastern side of the Mississippi. On May 1, Confederate forces under General John Bowen had been hit hard by Grant’s Westerners at Port Gibson, just under 30 miles south of Vicksburg, and were forced to fall back. To add to the confusing reports from the field, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and Pemberton’s immediate superior General Joseph Johnston kept sending conflicting orders. Faced with an enemy army at his immediate rear, with the real consequences of a prolonged siege and inevitable defeat, Pemberton panicked. He sent messages out for help from Johnston, 28 miles away in Jackson, Mississippi.

General Johnston’s response was always the same: Abandon Vicksburg, link up with his small army of 12,000 men, to be reinforced, according to the Confederate government, with 15,000 more, near Canton, Mississippi. With Pemberton’s 23,000 men added, and the additional reinforcements, the Confederate forces might be strong enough to drive the Federal Army of around 44,000 against the Mississippi River and toward destruction. But the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, had other ideas for Pemberton and his forces, issuing orders to hold Vicksburg at all costs, thus buying time for the needed reinforcements to be raised.

With these contradictory orders in hand, the commander of the Vicksburg garrison had the beginnings of a military oxymoron. If he followed one order he would be disobeying the other. Pemberton decided that the middle ground was to attack Grant’s rear guard, destroy his supply lines, and force the Union armies to retreat.

Accordingly, in the early morning of May 13, the three divisions of generals Bowen, Loring, and Stevenson marched out from the Black River fortifications and began their strike toward what Pemberton hoped was the rear supply line of the Federal Army. The morning started off optimistically for the Confederate forces; the men were in good spirits and their commanders felt good about finally attacking at the Federal army that had invaded their territory.

What Pemberton did not know was that Grant had severed his base of supplies and was feeding his army off the rich fields and stock of the locals. More importantly, Grant knew Pemberton was coming. One of the messengers between Johnston and Pemberton was actually a Union operative who turned over his messages to General McPherson, who in turn reported the information to Grant. On the morning of May 16, 1863 the butternut defenders of Vicksburg met, not Grant’s supply line as expected, but most of his Federal Army at a place known as Champion’s Hill.

The ensuing battle went incredibly bad for Pemberton. The Confederate Army was nearly annihilated because of his mismanagement and the insubordination of his division commanders. Now the defeated, retreating Southerners were strung out on the road toward the earthen fortifications near a railroad bridge between Edwards and Bovina, crossing a small river called Big Black.

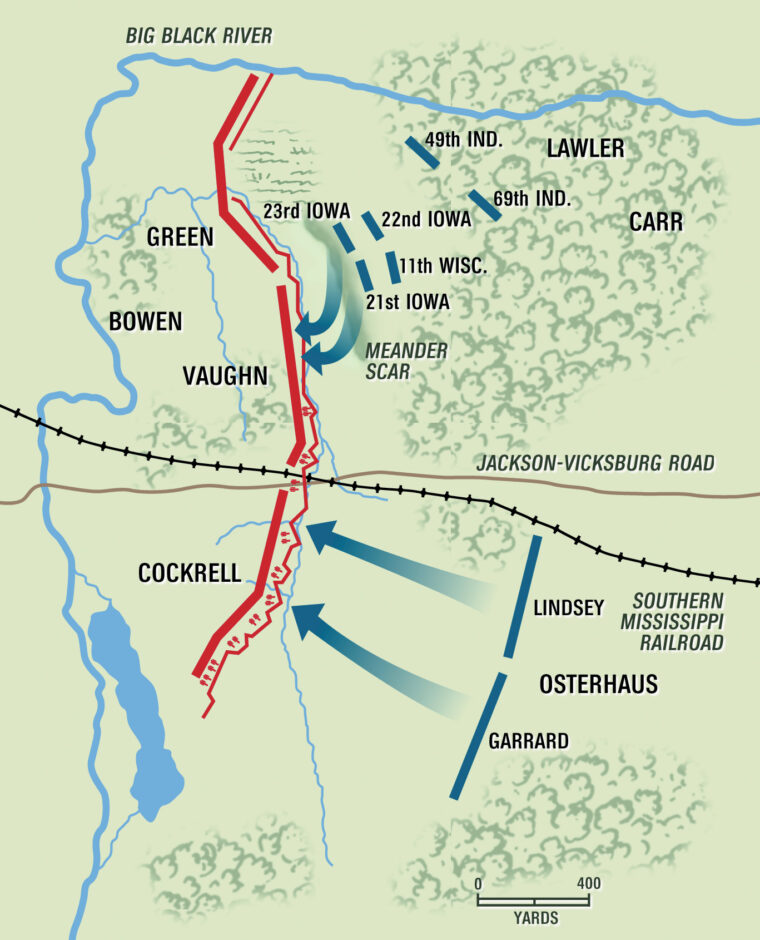

The fortifications built there earlier by the Confederate defenders were well placed. Confederate chief-engineer Samuel Lockett selected this position with well-considered intentions. Here the river, flowing south, turned west to follow the road to Jackson and the Vicksburg and Jackson Railroad. Then it made another sharp bend south. The banks in this bend were steep and impossible to guide around, and an attack would have to come across open, flat, low-lying, cultivated fields that sometimes flooded in the spring rains. The field itself was bisected north-to-south by the east-to-west running road and railroad. The cultivated field to the north of the railroad had dense woods and brush a little over four hundred yards from the earthworks. These woods ran parallel to the earthworks, creating two large open fields, both showing recent furrowing, but barren of crops.

Approximately 50 yards in front of the earthen ramparts, stretched a bayou, 10 to 20 feet wide and waist to shoulder-length deep. To make the bayou obstacle more formidable, trees had been cut down and placed on the defenders’ side of the bayou with some tops partially submerged into the water; the tops of the trees faced the attackers and their ends were sharpened to make a thick, deadly abatis. South of the railroad cut the mile-wide cultivated fields did not have woods, nor a bayou, but could be covered by several Confederate batteries that could sweep this entire area with deadly fire.

The earthworks themselves were most menacing, the ramparts’ exterior was very steep, making any attempt to climb the walls difficult and slow at best. Cannon fire would do little damage to the earthen fortifications, as the packed soil would simply absorb the round or deflect it harmlessly overhead. The anchor of the southern section rested on an impassable swamp called Gin Lake, which was doubly reinforced by strategically placed riflepits. The southern section also had the most artillery embrasures, but the bisecting railroad cut blocked the artillery’s line of sight to the northern section of the works.

This northern section had only a few embrasures for artillery. Lockett felt the natural barriers made a frontal assault here suicidal. He also thought that, because the woods allowed only four hundred yards of ground to be covered by cannon, artillery would be impractical. To help make up for the lack of cannon, the northernmost anchor of this section of the defenses was a line of riflepits placed so that the defenders could fire into the flanks of oncoming attackers. Finally on the western bank, on top of 60-foot ridges overlooking the plain and the river below, were earthworks where more troops could give fire support to the defenders on the eastern bank.

The river also was a good obstacle for defense. The waters were high from rains, and the current was strong and deep. The defended high western banks would put anyone trying to force a crossing in a deadly situation. The railroad bridge that spanned the river was the only standing bridge left in the area, which, in order to increase the movement of the army and supplies, had been planked over days previous.

This still was not efficient enough for moving the large bodies of troops and supplies required, until someone realized that four small steamships, Dot, Charm, Paul Jones, and Bufort were trapped on the river when Grand Gulf was earlier occupied by Union forces. Thus, the steamer Dot was turned into a floating bridge by swinging it across the river just south of the railroad bridge, securing the stem and bow to the banks, stripping it of parts, and the cabin deck knocked through to allow troop movement. It would be by these two “bridges” that Southern troops could fall back over, or be reinforced from, one bank to the other.

There was just one major flaw to these impressive fortifications: They required Pemberton’s full army, which he was lacking. The Confederate Army that had marched out optimistically from these same fortifications days ago was now staggering back on the Jackson Road from their defeat at Champion’s Hill. Only one small brigade was left behind to maintain the defenses during the main army’s foray, Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn’s 60th, 61st and 62nd Tennessee Infantry regiments, all conscripted from Union-sympathetic East Tennessee. This brigade had been left behind because of the dubious loyalties of these regiments. Although most of the truly disloyal had already deserted, Confederate command had their suspicions.

When Pemberton rode into the works from Champion’s Hill he immediately gave orders to General Vaughn to have his brigade man the eastern works and send wagons and supplies to the west bank but, more importantly, to keep the road clear for the quick movement of the retreating troops that would soon be arriving from Champion’s Hill. Turning to one of his few trusted aides, Lieutenant James H. Morrison, Pemberton assigned him the task of relaying his orders to the division commanders as they arrived. Once this was done the Confederate commander rode the three miles west to Bovina to set up his headquarters.

Confederate General Carter Stevenson’s dispirited division began to trickle in first. Lieutenant Morrison told Stevenson to march his command on to Mount Alban, then a small town between Vicksburg and Bovina, but his men were so exhausted and demoralized he had them fall out and camp at Bovina. Here Stevenson waited for the remainder of his scattered command to reunite, which arrived slowly all night, from battalion-sized units to a few straggling bands of men. All through the night of the 16th these physically wasted and dazed men came shuffling into camp and quickly dropped to the ground, fast asleep.

Shortly before midnight General Bowen’s command arrived, low on ammunition and exhausted. Nevertheless, Bowen’s command structure remained stable and the soldiers’ morale was high, considering the meat-grinder position they held in the center of the Confederate lines at Champion’s Hill. Bowen, a Georgia-born Missourian, led his Missouri and Arkansas fighters in attack after attack on the slopes of Champion’s Hill, several times coming close to breaking the Union center, only to be hurled back, rally and attack again. Bowen now received his orders to file into the earthworks next to Vaughn’s brigade and hold the roads open for General William Loring’s troops meant to be right behind Bowen. Then, with the Confederate Army once again reunited, they would decide whether to hold the west bank of the Big Black or retire to the Vicksburg defenses. Either strategy would delay the Union advance long enough to rest and re-equip a majority of the shattered army.

What Pemberton did not know was that Loring and his much-needed division would never arrive. The long-standing hatred of General Loring for his commander was secret to neither officer nor enlisted man. Public displays of anger and outbursts between Loring and Pemberton had occurred frequently in the recent past. In fact, during the climax of the battle at Champion Hill, Loring ignored Pemberton’s order for him to support Stevenson’s assault on the Union lines. Without Loring’s support Stevenson’s attack quickly failed with bloody repulse.

Everyone assumed that Loring was right behind Bowen’s command on the road, but as the dawn of May 17, 1863 approached, there was still no sign, nor word, from General Loring. What no one knew was that Loring had abandoned Pemberton’s army and marched his division east toward General Johnston’s forces, where they would join up days after the fate of Vicksburg had been sealed. Speculation remains about whether Loring did this on purpose or, in his own words, that his route of retreat was blocked by large elements of Union General McClernand’s soldiers, thus forcing him to take the eastern roads. Later, Loring’s fellow officers said they saw no said host of Union troops blocking the division’s path. But, whether on purpose or by fate, Loring failed not only to reach Pemberton, but even to send him word. And now Pemberton waited for Loring with an exhausted army, depleted not just by Loring’s men but also by the thousands of casualties left on the blood-slick slopes of Champion’s Hill.

Ignorant of Loring’s whereabouts, Pemberton had to make a decision: abandon the eastern works and leave Loring to his own devices, or hold them a few more hours and hope his much-needed division would arrive, more than likely with the blue-clad Federals close on their heels. Faced with a certain siege at Vicksburg, and not wishing to abandon hope, Pemberton decided to hold a little longer.

General Bowen was put in charge of the bridgehead defenses. He did not like the idea of holding this position but, being a loyal soldier, he set about making the most of what he had. Bowen’s division was made up of two brigades of Missouri and Arkansas troops, commanded by his fellow Missourians Colonel Francis M. Cockrell and Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green. Colonel Cockrell and his crack Missouri brigade was sent to defend the southern end of the defenses, where Bowen felt that the Federals would surely strike. It was this portion of the line that offered the most room to maneuver a large assault, and the Jackson road, which the Federals would be marching down, entered the earthworks there.

Eighteen cannon were positioned in the southern works, but for some unexplainable reason the artillery teams were sent across the river to the west bank, making it impossible to withdraw the guns if the need should arise. The middle of the works was manned by Vaughn’s Tennesseans and the 4th Mississippi Infantry. The Mississippians, along with several Alabama regiments, had been sent to nearby Bovina from Vicksburg when Vaughn requested reinforcements upon being left alone to defend the works several days previous. The Mississippi regiment was immediately sent by Vaughn into the works while the Alabama troops were left in Bovina as reinforcements. The very northern section of the works was manned by Green’s brigade, except for Colonel Gates’ 1st Missouri Cavalry (dismounted) which had crossed the bridge the night of the 16th and camped on the western side. This left the northern riflepits deserted, but in the confusion no one noticed until morning. As a final gesture, Bowen placed two 24-pounder cannon on the western bank to overlook the field and bridge.

Pemberton meanwhile was busy sending detachments of cavalry to make sure that the Union Army was not moving around his flanks to cut off his retreat route to Vicksburg. He also wrote and sent various dispatches requesting help and giving his current position to General Johnston by several trusted messengers, for Johnston’s whereabouts were unknown to Pemberton. Unfortunately for Pemberton, he would already be retreating to the trap of Vicksburg by the time Johnston received the messages.

The morning of May 17 was one of excitement for the Union troops in the van of Grant’s victorious army. Union General John A. McClernand had division commanders generals Eugene Carr and Peter Osterhaus and their commands up and moving by 3:30 a.m. Carr’s division led the way as the high-spirited, battle-toughened veterans marched out of Edwards Station toward what promised to be a sultry, hot day. Throughout the early-morning hours the troops felt their way slowly forward, not being able to see but a few yards to their front in the inky darkness.

The 33rd Illinois Infantry Regiment comprised the forwardmost skirmishers, who were expecting trouble, for they were increasingly picking up Confederate stragglers as they moved west. Just as the streaks of dawn cut the sky, four miles from Edwards Station, and as the skirmishers of the 33rd were crossing a plowed field, they came under fire from Rebel pickets in the dense woods just ahead. Without hesitating, the Illinois men plunged ahead through the packed brush, flushing out their adversaries, only to come to a sudden stop at the edge of another plowed field. There, only four hundred yards before the Federal skirmishers, were the Rebel earthworks, extending as far as the eye could see in the early-morning light, lined with cannon and rifles. The men in blue fell back into the cover of the woods at the edge of the field north of the railroad cut, and sent a runner back to General Carr to report the situation.

Carr arrived around 8:00 a.m. and immediately sent forward the six cannon of the 1st Indiana Light Artillery Battery to take up position on either side of the Jackson road. He then ordered Brig. Gen. William P. Benton and his Illinois and Indiana brigade into the open fields to the north of the road, to support the cannon. Irish-born Brig. Gen. Michael Lawler, a very large Illinois farmer who had no qualms about using his fists to knock men down during his frequent bouts of anger, was ordered to move his Iowa and Wisconsin brigade a hundred yards behind the battery as support.

General Bowen was confused by the deployment opposite the Confederate center. He did not expect an attack here owing to the bayou, abatis and strongly positioned riflepits supporting the earthworks. Upon hearing that the northern riflepits were deserted the night before, he quickly found and angrily ordered Gates’ 1st Missouri Cavalry (dismounted) from the west bank back to the position they had left.

Union skirmishers and pickets picked up this movement almost immediately. Generals McClernand (who had just arrived) and Carr thought this placement was a Confederate preparation to make an assault on the exposed right flank of the Union lines. Immediately the order went to General Lawler to move his brigade to the right, into the strip of woods that bisected the two fields, to cover the left flank of Benton’s arriving brigade and extend the Federal lines to the river. At the double-quick the Iowan and Wisconsin troops rushed to their new position, closely followed by the four guns of the 2nd Illinois Artillery, Company A. But the artillerymen could not get their guns through the thick woods and so remained in the eastern cornfields behind the woods, supported by the 22nd Iowa Infantry from Lawler’s brigade.

Soon after this new deployment, General Osterhaus arrived with his division and was ordered to take up a position south of the railroad cut. Osterhaus ordered Colonel Lindsey, with his brigade of Ohio and Kentucky regiments, to form up eight hundred yards from the Rebel works. To cover the movement of his troops from the Rebels, Lindsey sent out the 16th Ohio as skirmishers. Once the rest of his brigade was formed, Lindsey and his men drove forward three hundred yards over clear ground. Confederate gunners opened upon Lindsey’s troops as soon as they stepped off and began to tear gaps in the blue lines. Shortly, the orders went out to the men to lie down and take cover in the furrows of the field. Osterhaus next ordered his other brigade, commanded by General Theophilus Garrard, to detach two of his regiments, the 49th and 69th Indiana, along with a two-gun section of 20-pounder Parrot Rifles from the 1st Wisconsin Battery, to support Lawler. With his remaining two regiments, the 7th Kentucky and the 118th Illinois, Garrard moved to support the left of Lindsey’s prone brigade and opened fire on the Rebel works. This action resulted in a loud exchange of fire with the Confederates, but with very little bloodshed on either side.

The remaining two sections of the 1st Wisconsin Artillery Battery were brought forward and placed just south of the railroad cut. The four Parrot Rifles drew the attention of the Rebel artillery, instantly exploding one of the Union limbers as the Wisconsin gunners were getting their pieces into action, wounding the battery’s captain and three artillerymen. Another flying fragment struck General Osterhaus in the thigh, with only minor effects, but enough to take him temporarily out of action. Brigadier General Albert L. Lee was placed in command of the division, whose only order was to have Garrard’s 7th Kentucky thrown out as skirmishers on the extreme left of the Union line.

Meanwhile the men of the 1st Wisconsin Battery, without flinching at the exploding limber, began to open fire on the Confederate works. Within a few minutes their position was bolstered by the 1st Indiana and 7th Michigan batteries. The Federal artillerymen soon got revenge on the Confederates by striking a cannon’s axle of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, taking the piece out of action. One Federal round startled General Vaughn by snapping the reins to the horse he was riding behind the lines of his Tennessee troops.

It was now approaching 8:00 a.m. and the butternut and gray defenders’ morale was beginning to quickly sink. They could see that with each passing minute more Union troops were arriving while they, themselves, were under-manned. The Confederate artillerymen only now realized that without their horse teams, they could not take their cannon with them if they had to withdraw. Adding to their apprehension was the increasing concern that if the center defenses were pierced by the Federals, both northern and southern wings would be cut off from retreat. Many Confederate soldiers began to wonder why they were not on the opposite side of the river, where the high banks were better suited for defense than this level area. The Rebel soldiers had no way of knowing that Pemberton was waiting for Loring’s division to arrive so they could do just that.

Already some southern boys began to slip from their positions and head west across the river. Noticing this change, Major Lockett sent a runner to Bovina to tell Pemberton that he feared the bridgehead would not hold and sought permission to destroy the bridges if the line collapsed. When Pemberton agreed, Major Lockett got to work. He had barrels of turpentine put aboard the steamship Dot and turpentine-soaked bails of cotton placed on the bridge. Each was then posted by a trusted officer armed with a flaming torch, under the strict orders to wait for the command to ignite their stations. Pemberton, meanwhile, found and ordered the Alabama brigade that had been sent earlier to Bovina as reinforcements up to the earthworks on the western bank overlooking the bridge. But their advance was slow.

As the Union artillery barrage increased, the Confederate commanders were confident that the assault would come across the open fields on the southern end of the line. By military doctrine, this was the only part of the field where assaulting columns could form up and be supported by artillery. Bowen and his fellow commanders felt that if the first attack could be thrown back it would buy enough time to get the army across the bridges to the safety of the western bank. What the butternut leaders had not counted on was that the Iowa and Wisconsin troops of Lawler’s Brigade were undaunted by the prospect of assaulting the heavily fortified left wing of the Confederate line.

One reason was that at the treeline four hundred yards from the works, Lawler had just received information that an old river meander scar rose near the river and where he could hide his small brigade closer to the Rebel earthworks. But the only way of getting there was by running a hundred yards across a flat field under heavy fire from the entrenched Confederates. To test the possibilities of success, Lawler ordered the 11th Wisconsin forward. The men rushed toward the scar without hesitation, costing them a few men to the startled Confederate sharpshooters. After the Wisconsin men made it into the scar, the 21st and 23rd Iowa made their dash forward and took cover in the cut, suffering only a few minor wounds.

Lawler, still in the timberline, noticed a small path cut through the woods by a local farmer to move a small wagon between the eastern and western fields. He realized that two cannon could be placed on this path and sent word to the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery. Instantly a section of artillery was sent, and the 22nd Iowa moved to the left of the two pieces. The Illinois artillerymen now had a clear field of fire on the Confederate earthworks and the riflepits.

With this done, Lawler spurred his horse forward to the scar and, with minie’ balls whistling past him, galloped into the scar to join his men. There he ordered Iowa sharpshooters to line the top of the bank and fire upon the Rebel riflepits, creating a fierce exchange between the Iowans and the Rebels. Until support came to fill the gap in the Union line his brigade had just vacated, this was as far as Lawler could go, otherwise the Federal right flank would be “in the air.” It was now around 8:30 a.m. and those men in the scar not firing at the Rebel sharpshooters tried to huddle in the shady slopes of the scar for some relief from the quickly building heat.

After several minutes, a brigade of General A.J. Smith’s division arrived, sent by General William T. Sherman earlier to support the push onto Vicksburg. This welcomed relief was ordered into the spot that the Iowans had just left in their dash toward the earthworks. With this support arriving the 22nd Iowa rushed forward and joined their comrades in the meander scar. Meanwhile, the 49th and 69th Indiana moved up to take over the spot the 22nd Iowa had just vacated.

It was now 9:00 a.m., and already the heat was forcing the 250-pound Lawler to strip off his uniform coat and re-sling his sword belt over his shoulder, because his girth was too large to put the sword belt around his waist. He was looking over the bank contemplating what to do next when Colonel William Kinsman, commander of the 23rd Iowa, came forward and proposed that his regiment make a bayonet charge on the Rebel works.

Lawler, though impressed with the valor of the proposition, asked how the young colonel could do such a thing with the small numbers he had in his regiment against the Confederate thousands inside the earthworks. Kinsman pointed out that since they were so close to the enemy works, the defenders would probably only get off one to three volleys before the Iowans would be on them. Also, Kinsman, keen to the psychology of warfare, was betting heavily that morale in the Southern ranks was low owing to their devastating defeat the day before at Champion’s Hill. With a good strong push now, the Iowans could rout the Rebels from their works.

Admiringly, Lawler agreed to Kinsman’s argument, but the Hawkeye colonel would not go alone. Lawler instantly sent the order to his other regimental commanders to have their men fix bayonets. Lawler then ordered that more trees to be cleared to widen the narrow trail for the two pieces from the Illinois Battery. After this was done the 1st Wisconsin Artillery could bring up another 20-pounder Parrott to help support the coming assault. The colonels of the 49th and 69th Indiana were asked to throw a skirmish line out to distract the Rebel defenders, and then follow in close support when the attack was made.

To pack more of a punch, Lawler assembled his men on a two-regiment front instead of a broad brigade front as described in the military handbook. The 21st and 23rd Iowa were in the lead and the 22nd Iowa and 11th Wisconsin directly behind. Orders were given that no one was to fire until almost on the Rebel works, then to continue moving and give the enemy the bayonet. Satisfied that he did everything he could to prepare for the assault, Lawler mounted his horse.

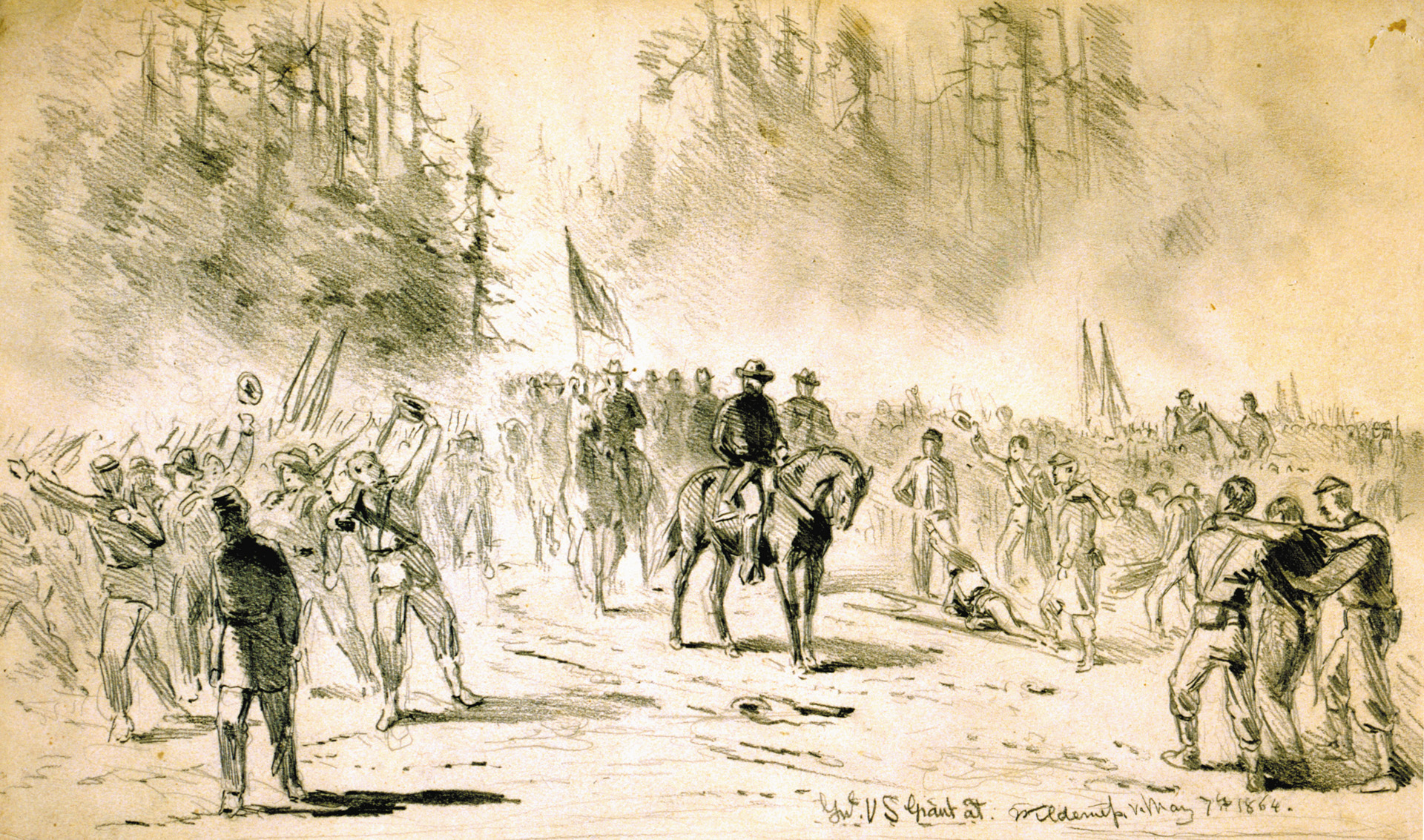

General Grant arrived that morning and considered the earthworks before him formidable, but he felt they could be taken, and sent a dispatch to Sherman saying as much. He realized that the casualties would be high when the final assault was ordered, but hoped to capture the bridges before the Rebels could destroy them.

As Grant was considering these challenges, standing near his 12-year-old son Fred who was accompanying him on the campaign, up galloped a lathered horse and rider. The man was a courier, and he handed General Grant a dispatch from Grant’s superior, General Henry Halleck, in Washington. Opening the message, Grant noticed it was dated the 11th, and had been sent first to the New Orleans headquarters of General Nathaniel Banks who then sent the message on via the runner.

The message said that Grant was to stop his movements immediately, move south to Louisiana and support Bank’s army in his attempts to capture Port Hudson; then he could return to his Vicksburg campaign. Grant informed the messenger that the commanding general would not have sent the message if he knew how close the army was to Vicksburg.

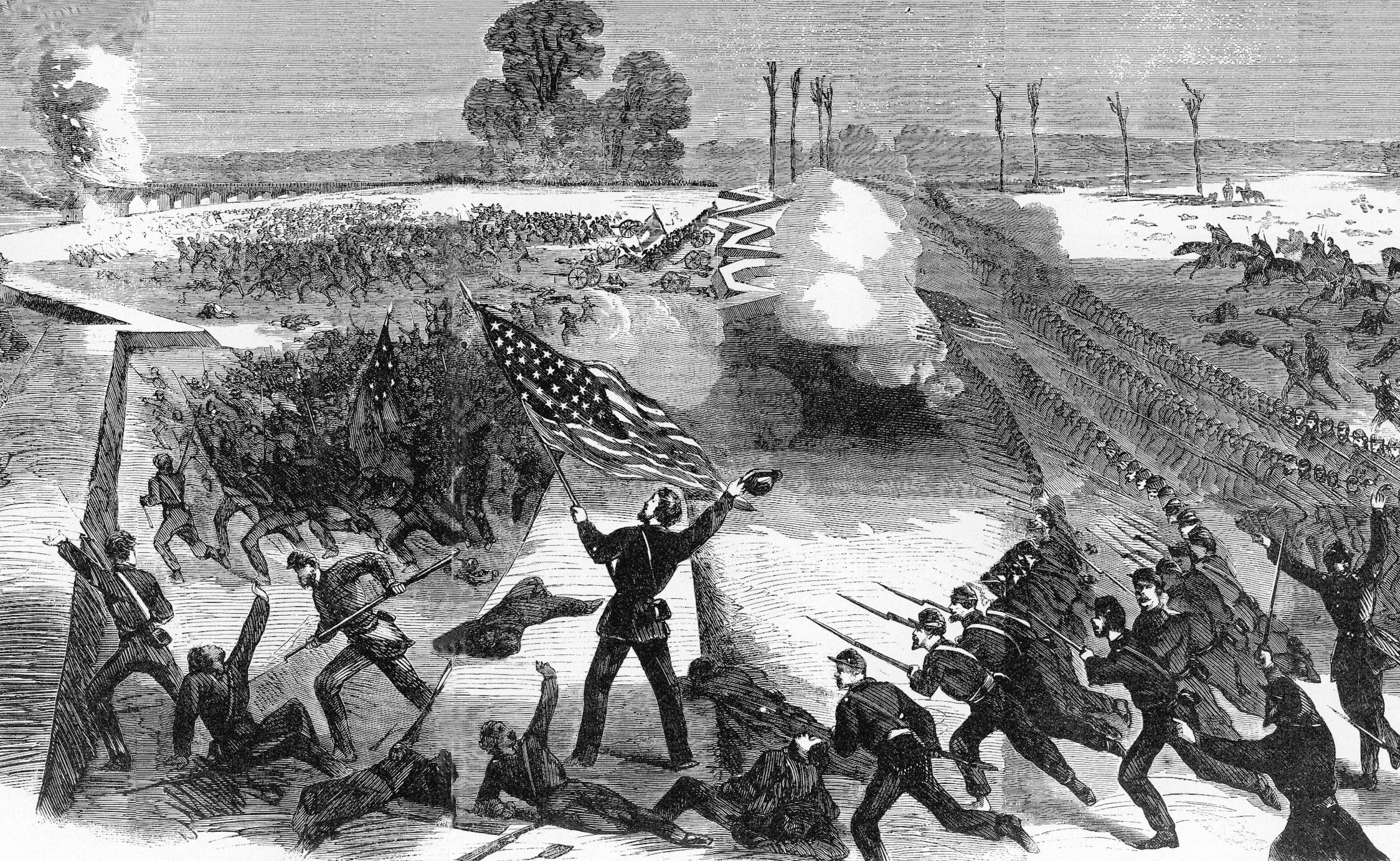

The officer who delivered the message began to argue with Grant that he should not disobey the order and had just started his reasons when everyone’s attention was diverted by a loud cheering. The holler was from Lawler’s men who with a howl burst from the meander scar toward the Rebel works, still over three hundred yards to their front. Grant quickly mounted his horse and rode closer to the action, and he never saw the shocked messenger again.

A surviving major of the 21st Iowa later described the moment: “To stop one instant was to die, and so onward they rushed, yelling, screaming madmen, wild with excitement, and shaking the gleaming bayonet. We have heard much said of the rebel yell, but surely no yell could create more dismay than that which burst from those Iowa troops on that beautiful May morning.”

Gate’s Missouri sharpshooters in the riflepits got off only a few quick volleys almost point-blank into the Union flanks when the charging men passed by on their headward rush toward the center of the Confederate line. The Missourians inflicted heavy casualties in that short time, including Colonel Merrill of the 21st Iowa, who was shot through both legs. Also struck was Colonel Kinsman, the man whose idea the assault was. Rising after being struck once, he pushed forward shouting encouragement to his men when a second minié ball struck him in the chest and punched through his back. He died on the field an hour later, and requested that he be buried with his men. Now both lead regiments had lost their colonels, but their places were quickly filled. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Glasgow took over the 23rd Iowa and Major Salue G. Van Anda took over the 21st Iowa. The charge continued.

The men inside the earthworks fired with desperate fury into the oncoming ranks. Constantly obliquing to the left past Green’s stunned brigade, the Federals were now directly before the center of the works manned by Vaughn’s 61st Tennessee Regiment. At a full run the Federal men reached the bayou, their parade-like lines breaking apart in the rush. They fired one ragged but devastating volley at the Tennessee men behind the works and then jumped into the stagnate abatis-filled waters.

Men jumped from log to log or hit the abatis wall like cyclones, knocking limbs down or snapping them off with their rifles and bodies, ignoring ripped clothing and flesh. Iowans tore through the abatis and waters as if they were not even there. Some got hung up on the obstacles; some drowned; and soon enough dead and wounded bodies hung in ghastly positions from the unforgiving limbs of the cut trees.

But cross the bayou they did, and then rushed the base of the earthworks. Still under fire they began their climb up the earthen slope. Corporal John W. Boone, the color bearer of the 23rd Iowa, was shot down near the earthworks, but the colors were grabbed before they hit the ground by Corporal John T. Shipman and were carried through the rest of the charge.

Even civilians took part in the fight. Old man A.M. Lyon was the sutler for the 23rd Iowa and had sons in the regiment. When the battle started he grabbed a rifle and went with his sons into the charge, only to fall mortally wounded near the fort.

Lawler shouted for the 49th and 69th Indiana to join the assault. The Hoosiers advanced to the left of Lawler’s brigade and fired another volley into the Tennesseans’ faces, then also crossed the bayou and abatis. The Union artillery now shifted targets from the fort and began firing on the riflepits, forcing the Missourians there to keep down. As the screaming Hawkeye men reached the peak of the Confederate earthworks, they found that most of the conscripted East Tennesseans had fled toward the bridges and the remainder were holding up their ramrods with pieces of cotton attached, a sign of surrender. The elated Northerners swarmed over the earthworks and into the fort, rounding up prisoners and trying to force their way through the surrendering mobs toward the bridges.

From beginning to end, the charge had lasted just three minutes, the shortest in the war. The two lead regiments, the 21st and 23rd Iowa, took the heaviest losses, with the 23rd Iowa Regiment losing 101 men, the highest in Lawler’s Brigade. In all, the heavy Irishman’s brigade had combined losses of 221 men out of the 279 total casualties XIII Corps suffered in the battle. A newspaper reporter who watched the charge wrote, “It was the most perilous and ludicrous charge I witnessed during the war.”

The 33rd and 99th Illinois from Benton’s Brigade of Carr’s Division, who were stationed on the right of the Union line, had moved to the left of the 49th and 69th Indiana Regiments for the final assault and together helped collapse the Rebel line as far south as the railroad cut. Here, Private James S. Adkins of Company K, 33rd Illinois, filled with the excitement of the victory, jumped astride the barrel of an abandoned Confederate cannon, crowed loudly while flapping his arms like a rooster, and then pulled the lanyard. The ensuing discharge of the cannon knocked the foolhardy private onto the dust and sent a shell hurtling over the heads of the supporting regiments, luckily without injury.

When Lawler crested the works he saw nothing but the chaos of fleeing Confederates to the north and south. Realizing they were soon going to be cut off, Green’s Missouri and Arkansas troops ran rearward as soon as they saw the first blue-clad soldier appear on top of the works.

Lawler had gained a great success, but did not know what to do with it. He wanted to push forward, but there were so many fleeing and, though surrendering, still armed Rebels in this whirlwind that he had to detach the 2lst and 23rd Iowa plus the 49th and 69th Indiana regiments to gather up and disarm the prisoners. He then sent the 11th Wisconsin and 22nd Iowa to attack the riflepits and cut off any retreat there.

There was never an attack. Confederate Colonel Gates and his soldiers were already cut off by the 11th Wisconsin. Faced with surrender or swimming for it, many tried the latter. Some made it to the opposite shore, but their fellow Missourians watched in helpless horror as several of the men drowned in the strong current. Many still on the east bank could not swim, or were reluctant to try, and some 90 men of Gates’ command begged their colonel to stay with them. Gates, moved by their pleas, stayed and surrendered to the Wisconsin troops. A few days later, though, Gates made his escape and fled to Vicksburg, ironically only to again surrender the remainder of his command when that city capitulated on July 4th.

To the south, Cockrell and his Missouri brigade, which had fought so bravely in the past, saw the center falter and knowing the outcome ran pell-mell for their lives at the same time the southern end of the Union line launched its attack. The approaching Federal units were confused when they received no fire from the Rebel works. But when the blue lines were two hundred yards from the defenses they could see why. White flags were raised, and the Confederates before them were surrendering. The 60th Tennessee had delayed too long and now, after moving southward trying to escape, found that they were cut off in all directions. Their colonel surrendered to the first Federal officers he saw.

General Osterhaus, ignoring his wound in the excitement, saw the Confederates fleeing across the bridge, mounted his horse and rode to the 1st Indiana and 1st Wisconsin batteries nearby, then directed their fire toward the bridge. With the grim satisfaction, he saw that the shots began to dash or knock fleeing troops off the bridge into the waters below.

Major Lockett was panic stricken, but was somewhat relieved when the Alabama reinforcements, sent by Pemberton that morning from three miles away, arrived and took up position on the western bank overlooking the bridges. Lockett waited for the majority of the routing fugitives to cross, then at the last possible moment, ordered the bridges torched, himself starting the fire on the Dot and was the last to leave the ship.

General Grant’s son, Fred, became so excited by the quick victory that he rode his horse over the works with the soldiers. He stopped to watch the Rebels swim the river when a Confederate sharpshooter on the west bank fired, hitting the lad in the leg. The wound was slight, but very painful to the boy.

With the Union advance momentarily halted, the Confederates left a small force to harass the Federal troops from the western banks and began their final shameful retreat toward Vicksburg. During the few minutes of the charge and capture of the earthworks the Vicksburg army lost five stands of colors, 1,751 men as casualties or prisoners, 18 cannon, 1,525 rounds of artillery rounds, and over 1,400 stands of small arms.

Riding back toward Vicksburg, Lockett was next to Pemberton who, in obvious depression, said, “Just thirty years ago I began my cadetship at the U.S. Military Academy. Today, the same date, that career is ended in disaster and disgrace.” He was not alone, for years after the war, during regimental reunions, few Confederate soldiers who attended were able to speak of the battle at Big Black River without feelings of bitterness and shame.

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge was a huge success for the troops of Grant’s army. Grant himself was upset that the bridges were not captured before they were torched, but by evening, several new bridges had been cleverly constructed and the army crossed the Big Black with bands playing. For the Iowa troops it was a sad and proud moment. They buried their dead on the field of battle, including their beloved Colonel Kinsman. Yet they had swept the enemy from a heavily fortified position, against superior numbers, across open fields and over obstacles under constant heavy fire. Even though this battle would be quickly overshadowed by Vicksburg and Gettysburg, many of Lawler’s men who survived the war remembered this victory as one of the proudest moments of their military careers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments