By John Walker

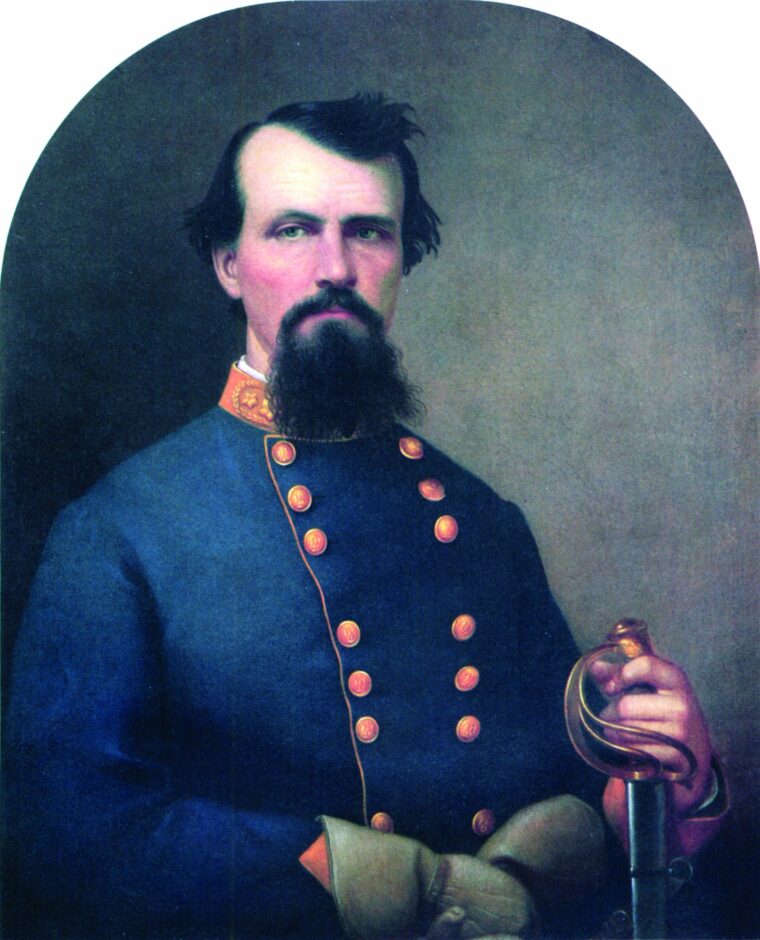

After critical victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga in 1863, the Union high command had ambitious plans for the Civil War’s vast western theater in the spring of 1864. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 100,000-man army would bisect the Confederacy from Chattanooga to the Atlantic coast and destroy General Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in the process. Sherman’s first objective was the invaluable city of Atlanta. His massive troop movement into northern Georgia was supported by single-track railroads in southern and central Tennessee and northern Alabama that linked him to Federal supply depots. This crucial lifeline was particularly vulnerable to attack from the southwest—the area of operations controlled by the redoubtable Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the South’s last and best hope of slowing down Sherman’s inexorable drive into the heart of the Confederacy.

“Remember Fort Pillow”

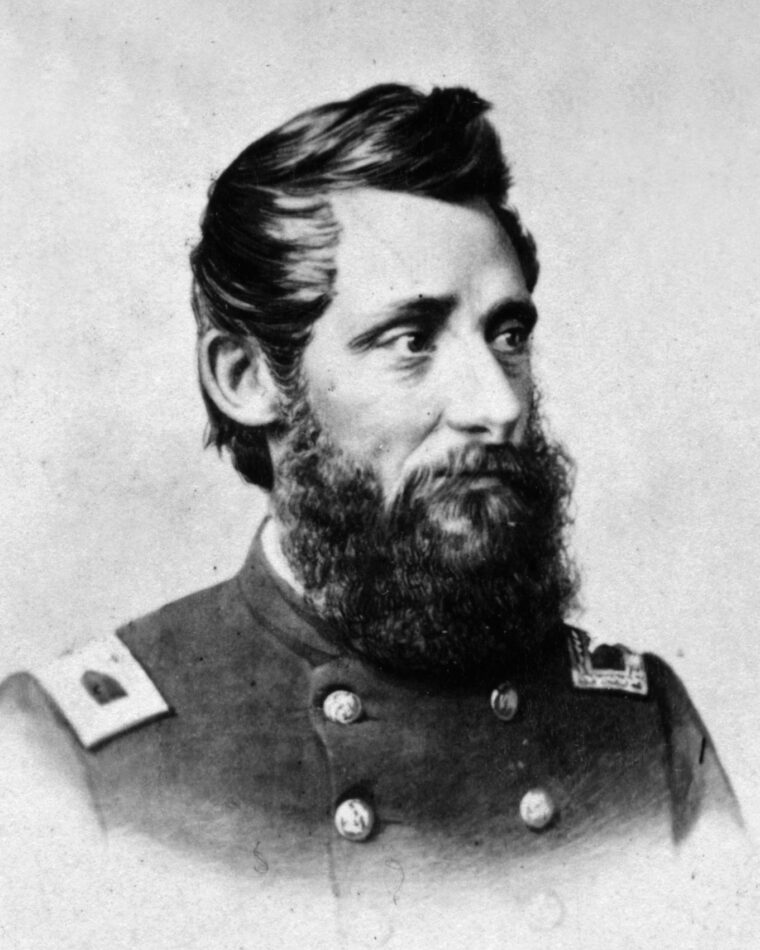

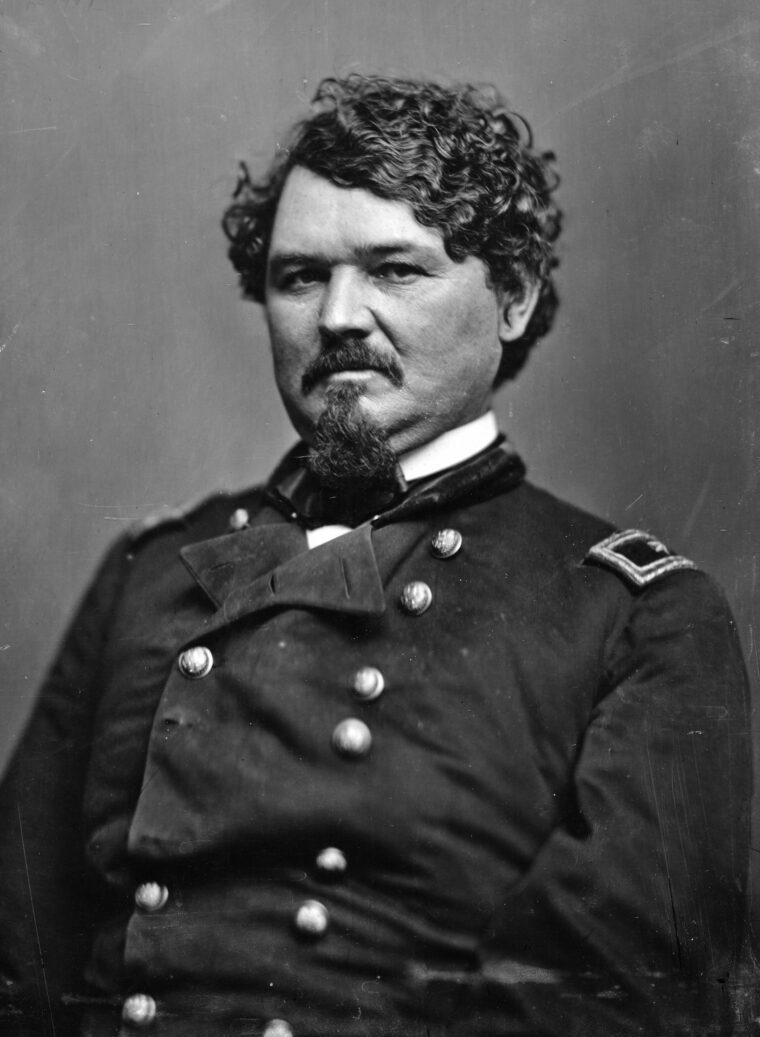

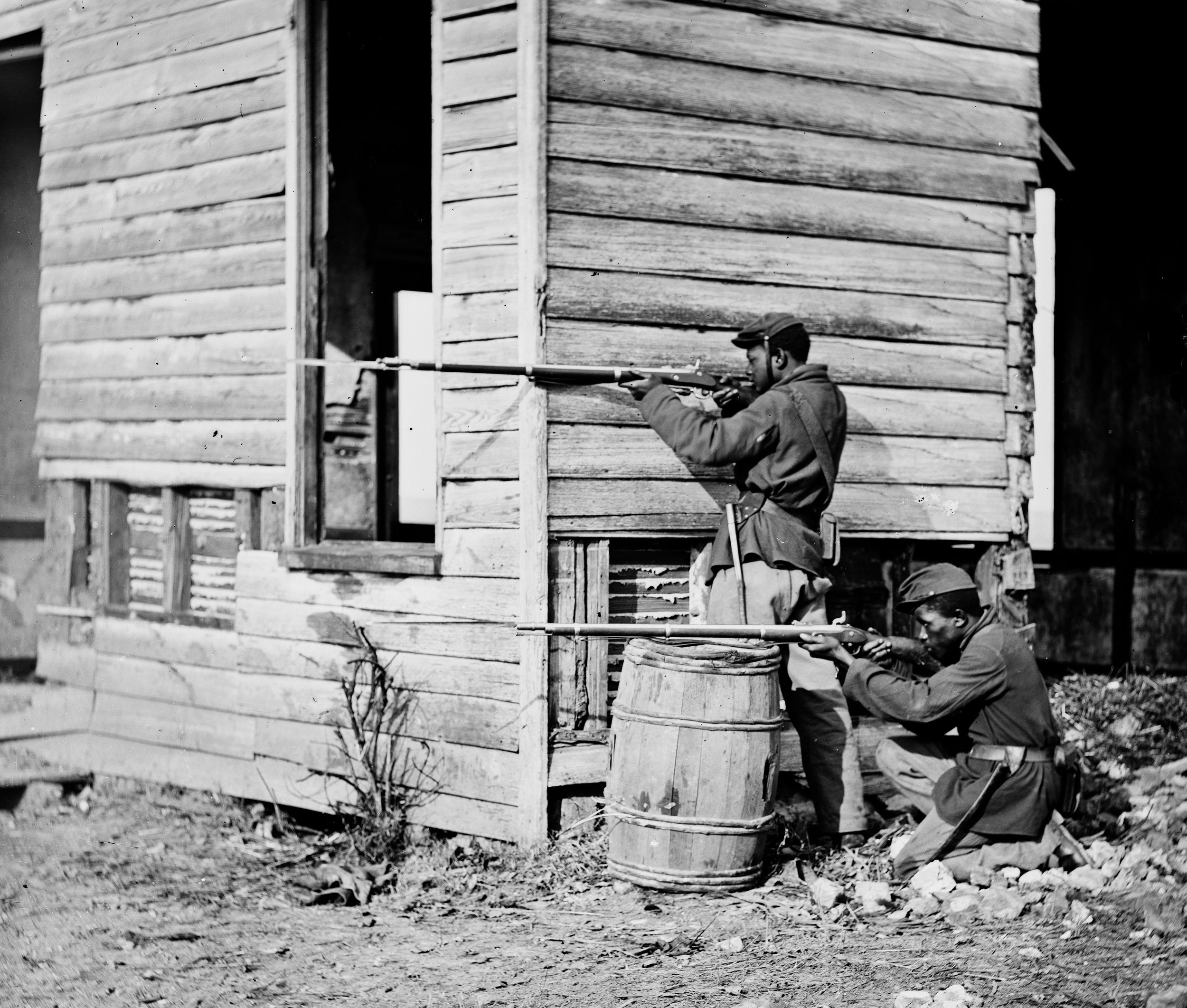

Sherman’s Georgia campaign was well under way by mid-1864. Cognizant of the significant threat Forrest posed, he ordered the newly installed West Tennessee commander, Maj. Gen. Cadwallader Washburn, to launch a “threatening movement from Memphis” into Mississippi to prevent Forrest from “swinging over against my communications.” Maj. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis would lead the incursion. Washburn assembled a mixed force of 8,300 troops, some of whom had fought against Forrest before: three brigades of infantry under Colonel William McMillen, two brigades of cavalry under Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson, and 400 artillerists. Sturgis had 22 artillery pieces of various calibers and 250 wagons and ambulances loaded with a 20-day supply of food and ammunition (northern Mississippi by then was stripped bare of forage). There was also a racial element in the equation—one of McMillen’s infantry brigades, commanded by Colonel Edward Bouton, consisted of two black regiments whose members had vowed to avenge the alleged massacre by Forrest’s men at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, two months earlier. The black infantrymen wore badges reading “Remember Fort Pillow.” Neither Forrest’s nor McMillen’s troops could expect mercy if the two forces came to grips.

Forrest left Tupelo, Mississippi, on June 1 with 2,400 troopers and six cannons for a strike on Sherman’s fragile lifeline below Nashville, the same day the tardy Sturgis left Memphis. With intermittent rain falling, Sturgis’s expedition set out on the evening of June 2, Grierson’s cavalry brigades in the lead. The Union column was to cross the border into Mississippi and march for Corinth via Salem and Ruckersville. After capturing Corinth and destroying all public property, Sturgis would strike south for Tupelo, tearing up the Mobile & Ohio Railroad as he advanced.

Sturgis Presses On

With Confederate regiments scattered widely about Mississippi, departmental commander Maj. Gen. Stephen Dills Lee had no option but to recall Forrest to Mississippi to deal with the threat posed by Sturgis. Unsure if Sturgis’s objective was Corinth or Tupelo, Lee instructed Forrest to dispose his troops along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad between the two cities, ready to move in either direction. Meanwhile, Lee would do what he could to gather reinforcements. Lee wanted Forrest to draw Sturgis away from his base of supplies in Memphis and southward toward Okolona, where the two Confederate commanders could combine and fall upon the larger Union column.

Forrest had 4,300 horse soldiers within reach: 2,800 in Colonel Tyree Bell’s brigade and about 750 men in each of two small brigades commanded by Colonels Hylan Lyon and Edmund Rucker. In compliance with Lee’s orders, Forrest dispatched Bell’s large force north to Rienzi on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, while Rucker, Lyon, and Captain John Morton’s artillery marched together to Booneville, nine miles south of Rienzi. A 500-man brigade under the command of Colonel Edmund Johnson, which would enlarge Forrest’s corps to 4,800 men, was riding hard from Alabama to lend their aid.

On June 3, the blue column was slowed by heavy rains that flooded fields and turned the narrow roads to mud. McMillen’s infantry column, held back by the slow-moving wagon train, managed only seven miles a day and fell far behind Grierson’s cavalry column. The rain continued on June 4 and 5; at mid-morning on the 5th, the wagon train and infantry made it to Salem, reuniting with the cavalry that had arrived 40 hours earlier. When the rain finally stopped that afternoon, Grierson’s horsemen broke camp and rode 13 miles to Dunbar’s Mill, a few miles west of Ruckersville. There, Grierson dispatched Colonel Joseph Karge and 400 horsemen to strike the M&O Railroad at Rienzi and cut the telegraph wires to confuse the enemy as to Sturgis’s true objective.

Rain continued falling on June 6. Karge’s troopers crossed the Hatchie River and galloped into Rienzi, dispersed a small number of Confederates, cut the wires, and continued north up the line of the railroad toward Corinth. High water, however, forced the column to turn back. Karge’s mounted force, after being isolated by the flooding Hatchie, would not rejoin Sturgis until the evening of June 8. Sturgis’s entire command gathered in Ruckersville on the 6th; the next day, after Sturgis was notified that Corinth was empty of Confederates, he changed direction and marched toward Ripley. Sturgis hoped to interdict the enemy by moving southeast on the Ripley-Guntown Road and seizing the railroad near Baldwyn and Brice’s Cross Roads. The entire Union command camped at Ripley that night; in deference to the city’s populace, the two colored brigades slept outside the city.

Sturgis, discouraged with the progress of the expedition and afraid that Forrest would use the time to concentrate an overwhelming force against him, contemplated turning back. After he conferred with his division commanders, however, he decided that the Federal column would press on despite the risks involved. Sturgis had no idea of Forrest’s location. The local residents he encountered gave him no help, and he discounted the reports he was given by runaway slaves who flocked to his lines. Late in the afternoon of June 8, the Union column resumed the march, traveling about four miles southeast before stopping for the night. The next morning, the blue soldiers continued down the Ripley-Guntown Road through hilly, sparsely populated countryside. After a difficult 10-mile march, the Federals halted at Stubb’s Farm, camping on a ridge nine miles northwest of Brice’s Cross Roads.

March on the Cross Roads

Lee and Forrest met at Booneville on June 9. Lee was now certain that the Federal objective was Tupelo, 12 miles below Guntown. He wanted Forrest to concentrate his men at Okolona. To get there, Forrest’s units would have to march through Brice’s Cross Roads. After Johnson’s Alabama brigade arrived and Forrest met with his staff, he came up with a plan. Although he would be heavily outnumbered and outgunned, he would strike the Union column before it reached Guntown. Orders went out that night to each Confederate command to march for Brice’s Cross Roads before dawn the next morning. Forrest’s troops were scattered and all but one would have farther to travel to reach their objective than the Union column. Bell was at Rienzi, 25 miles from Brice’s; Rucker, Lyon, and Morton were at Booneville, 18 miles distant; and Johnson was at Baldwyn, five and a half miles from the crossroads.

The rain stopped on the morning of June 10, a harbinger of long hours of merciless heat and humidity. Forrest and his men were up well before dawn. When it was light enough to see the road, Forrest rode out the Baldwyn Road at the front of Lyon’s lead brigade, followed by Rucker and Morton’s artillery. Johnson would come in from the east. Forrest was accompanied by his usual 85-man escort, plus an additional 50-man escort company of Georgia troopers under Captain Henry Gartrell.

Sturgis was pleased that the rain had stopped, but he prepared to continue his march with serious forebodings. Despite his earlier resolution to move forward, keeping his force as compact as possible, Sturgis allowed his infantrymen almost two extra hours to rest, eat, and get ready for what promised to be a long, hot day. Grierson’s cavalry brigades, with Colonel G.E. Waring in the lead and Colonel Edward Winslow’s Iowans behind him, moved out at 5:30 am in the direction of the crossroads. The first infantry units did not get under way until well past 7. After a three-mile march, the cavalry began crossing the mile-wide Hatchie River bottom, where the road was a ribbon of mud. Their horses churned the mud even more, boding ill for the infantry column that would come behind them.

Sturgis joined McMillen at the head of the infantry as it moved out; behind came Colonel George Hoge’s brigade, followed by that of Colonel Alexander Wilkin. Bouton’s black troops brought up the rear, guarding the more than 200 wagons. When the infantry descended into the river bottom, pioneers were called up to corduroy the road, further delaying the infantry and wagons. Before long, the Union column was strung out, nose to tail, for at least eight miles. As the sun grew warmer, Union and Confederate units, both infantry and cavalry, continued to converge upon the crossroads from various places around Lee County.

“We Will Ride Right Over Them”

Forrest was confident, as always, despite the fact that the enemy held close to a two-to-one advantage in numbers and nearly three times as many guns. “I know they greatly outnumber the troops I have at hand,” he told Rucker, who rode with him in advance of his brigade, “but the road along which they will march is narrow and muddy; they will make slow progress. The country is densely wooded and the undergrowth so heavy that when we strike them they will not know how few men we have. Their cavalry will move out ahead of their infantry, and should reach the crossroads three hours in advance. We can whip their cavalry in that time. As soon as the fight opens they will send back to have the infantry hurried in. It is going to be hot as hell, and coming on the run for five or six miles, their infantry will be so tired out we will ride right over them.”

Forrest soon found the going difficult as well; it was mid-morning before he reached Old Carrollville, five miles northeast of the crossroads. He called up Lieutenant Robert Black of the 7th Tennessee and told him to ride to Brice’s Cross Roads, turn northeast up the Ripley Road, and reconnoiter. After Black and his men reached the crossroads, they rode along the Ripley Road for three-quarters of a mile into the Tishimingo Creek bottom, the road bordered on each side by cornfields. The creek was spanned by a wooden bridge, a quarter-mile west of which the road forked, one road leading to New Albany, the other to Ripley. Moving up the Ripley Road, Black spotted Union cavalry—Waring’s advance party—and he and his men quickly wheeled their horses around and galloped away. Waring’s men pursued over the bridge and up the slope to the crossroads, where they turned left up the Baldwyn Road after Black’s troopers. It was by now about 10 am.

A short distance up the Baldwyn Road, Black’s men encountered Forest riding with his vanguard at the head of Lyon’s brigade. The lieutenant reported that 1,500 Union cavalry had arrived at Brice’s Cross Roads. Moments later, after he spotted the mounted blue column, Forrest called up Captain C.L. Randle of the 7th Kentucky and told him to take his company and charge the enemy. When they did, Waring, on the other side of the field 400 yards away, halted his column, dismounted his men, and unlimbered two guns, quickly driving the Rebels back. The Battle of Brice’s Cross Roads had begun.

Outnumbered, Outgunned

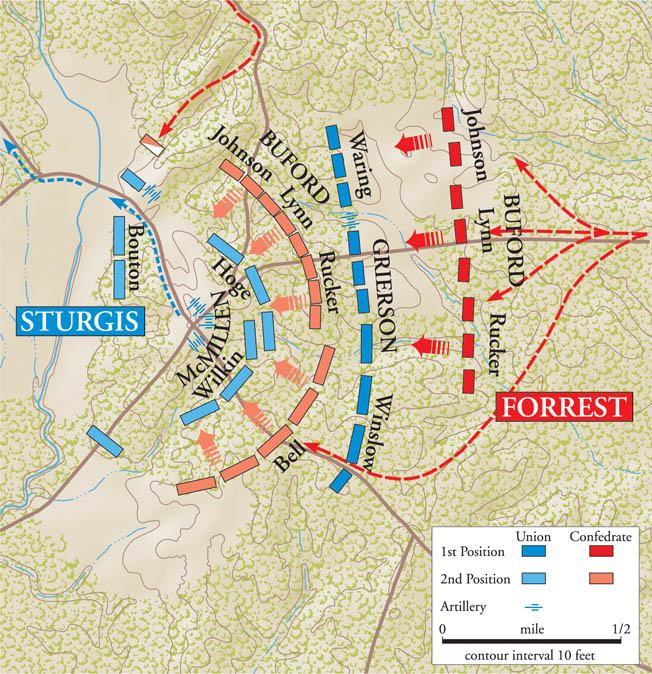

Waring deployed his 1,450 men astride the Baldwyn Road, half on the north side and half on the south. The large field to the Union front, about 2,000 feet northeast of the crossroads, was surrounded by blackjack and scrub oak, beyond which the ground was heavily timbered.

Forrest had Lyon dismount the 3rd, 7th, and 8th Kentucky Regiments and deploy them astride and south of the Baldwyn Road. He sent orders to the rear for the artillery to be hurried forward and for Colonel Clark Barteau and his 250-man 2nd Tennessee to take to the back roads and attempt to strike the Federal rear. Although he had no artillery closer than eight miles away, Forrest preferred to go on the offensive rather than wait to be attacked. He told Lyon to send his dismounted troopers across the field against the blue line in a strong demonstration. Lyon quickly threw out a double line of skirmishers and sent his men forward. Not only were Lyon’s Kentuckians outnumbered, they were outgunned as well. Waring’s 2nd New Jersey was armed with Spencer seven-shot repeating carbines, the 3rd and 9th Illinois had Colt revolving rifles, and Waring’s other troops wielded single-shot carbines.

Grierson had joined Waring and, surprised by the sudden assault, quickly concluded that he was facing not only cavalry, but infantry as well. Grierson sent a courier hurrying back through the crossroads and across Tishimingo Creek to inform Sturgis that he had encountered a strong enemy force and requested an infantry brigade be sent to his assistance. When the dispatch arrived, Sturgis and his staff were relaxing in the Hatchie bottom, watching the pioneers corduroy the road. Sturgis instructed McMillen to call up Hoge’s brigade and make a forced march to the crossroads. The artillery and wagons would follow when the road was ready. Hoge’s brigade, joined by Sturgis and his escort, set off for Brice’s Cross Roads.

Grierson called up Winslow’s brigade from the creek bottom, sending them out the Guntown Road on Waring’s right. By 10:45, Winslow’s 1,750 troops were in position and Grierson’s entire cavalry force was dismounted and ready to do battle. The blue left lay north of the Baldwyn Road and the right extended across the Guntown Road, its extreme right bent back toward the Brice home. After sending a fan of troopers with repeating carbines 100 yards to the front, where they concealed themselves in the thick brush, Grierson unlimbered two mountain howitzers and two rifled guns behind his crescent-shaped line, with six more guns in reserve.

Breaking Waring’s Center

Needing to buy time, Forrest again sent Lyon’s brigade forward. Some 800 Kentuckians boldly leaped over the brush fences to their front, moved across the field, and assailed the blue line. Grierson’s men opened up with withering volleys of musket fire and artillery blasts. Lyon continued his demonstration for 20 minutes, then fell back. As he withdrew, more Confederate reinforcements arrived in the persons of Rucker’s 750-man command, and Forrest immediately dismounted Rucker’s 7th Tennessee and 18th Mississippi and put them in line on Lyon’s left. The new arrivals doubled Forrest’s numbers—to about 1,630—but he was still outnumbered about two-to-one.

When Rucker’s troops were ready, Forrest once again ordered his line forward in a strong demonstration; after some sharp exchanges, the gray line withdrew once more. As the feint ended, Colonel W.A. Johnson arrived from Baldwyn with his 500 Alabama horsemen; Forrest dismounted Johnson’s men and sent them north of the Baldwyn Road on Lyon’s right, instructing them to move forward and engage the attention of Waring’s left. After some desultory firing, Johnson’s men fell back, exhausted from their recent trek. It was now almost midday and Forrest decided to try to break Grierson’s line with the three brigades he had on hand. Forrest rode along his entire line, encouraging his men, telling them he expected every man to move forward when the bugle sounded. This was not to be a feint but an all-out, desperate fight at close quarters. When the bugle rang out, the entire gray line sprang from the edge of the timber as one and rushed to close with the blue line.

The Union cavalrymen fought back viciously, their repeating rifles crackling away into a deafening roar. Rucker, at the head of the 7th Tennessee and 18th Mississippi, carried his line ahead fully 100 yards in advance of Lyon and Johnson and put tremendous pressure on Waring’s right unit, the 7th Indiana. Waring’s troopers fought heroically, but the Confederates would not be denied. As the enemy rushed toward them, Rucker shouted to his men to draw their six-shot repeating pistols and close with the enemy. After a brief but ferocious struggle, much of it hand-to-hand, Rucker punched a hole through the 7th Indiana’s line and Waring’s men began to pull back, first by ones and twos, then by squads, then by scores.

Johnson’s and Lyon’s men closed with the Union forces on the Union far left, while Duff’s mounted Mississippi regiment, on the extreme Confederate left, was vigorously engaged on the far right of Grierson’s line. As Waring’s center collapsed, Johnson and his Alabamians advanced so rapidly that he gained a foothold fully halfway between his original position and the road leading from Ripley to the crossroads. The Union cavalry brigades, exhausted and almost out of ammunition, were hard-pressed all along the line. Forrest was close to achieving his first objective—defeating the Union cavalry prior to the arrival of the infantry.

A Grueling Forced March

Meanwhile, Sturgis and McMillen had set a man-killing pace for the Union infantrymen; the roads were beginning to dry out, the sun was broiling, the humidity dreadful. The 113th Illinois, in one 2.5-mile stretch, had five men collapse with sunstroke, two of whom died. At Dry Creek, a short halt was called to allow the men to fill their canteens; then it was up and over the ridge and down a grade into the Tishimingo bottom. They crossed the bridge and double-timed up the opposite slope, a half mile away from the crossroads. Sturgis, his staff, and escort arrived on the field shortly after noon. What he saw was not encouraging; he conferred with Grierson, who pointed toward the Baldwyn Road, where Waring’s men were falling back, and toward the Guntown Road where Winslow’s men were still holding firm. Grierson implored Sturgis to hurry the infantry forward, reporting that his own troopers were exhausted and almost out of ammunition.

Sturgis’s situation was deteriorating rapidly. Word came back from Waring that his men were falling back, and Winslow notified Grierson that if he did not get assistance immediately, he would have to fall back as well. Sturgis turned to Lt. Col. Joseph Hess and told him to hurry out the Baldwyn Road and establish a roadblock to buy time for McMillen’s infantry to come up and relieve the cavalry. At this moment, Confederate shells began bursting around the crossroads, filling the air with shrapnel. Sturgis was facing a severe crisis: his cavalry brigades were either in retreat or on the verge of breaking, and two of his three infantry brigades were exhausted from their seven-mile forced march. Turning to McMillen, Sturgis told him to have Hoge’s infantry relieve Grierson’s cavalry brigades. McMillen rode back along the Ripley Road to urge the infantry forward. At that instant, Waring’s brigade collapsed. The two roads converging on the crossroads were “filled with retreating cavalry, led horses, ambulances, and artillery,” wrote McMillen, “the whole presenting a scene of confusion and demoralization.”

A short lull descended over the field as Forrest aligned his new arrivals. Morton’s and Captain T.W. Rice’s batteries had arrived after a difficult 18-mile march over narrow, muddy roads, followed shortly by Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford, Colonel Tyree Bell, and the latter’s 2,800-man brigade. Morton had moved his guns up in Lyon’s rear on the right side of the Baldwyn Road, unlimbered, and had already opened fire with immediate and considerable effect. Forrest put Buford in charge of the Confederate right, where Lyon and Johnson were fighting, and moved with Bell’s brigade to Rucker’s left, where he dismounted Bell’s men and extended the Confederate line westward of the Guntown Road. Farther to the left, mounted and ready to swoop upon the Union flank and rear, were two companies of Kentuckians under Captain H.A. Tyler.

Forrest’s Fight in the Woods

Bouton and his black troops, still guarding the wagon train, had toiled onward. They crossed Little Dry Creek, passed Dr. Samuel Agnew’s farm, descended a grade to the Dry Creek ford, and climbed the opposite slope to Ames Ridge overlooking Tishimingo Creek. It was almost 2 pm. There was not a cloud in the sky to blot out the burning rays of the sun, which had already taken a fearful toll on the men and animals on both sides. Forrest once more prepared to move his outnumbered line forward. He told Buford to resume the assault on the Union left and center with Johnson’s, Lyon’s, and Rucker’s brigades the moment he himself hurled Bell’s dismounted Tennesseans against the enemy’s right.

Pushing their way through thickets and almost impenetrable undergrowth, the attackers advanced to within just a few paces of the Federal line, where they were hit with a horrific blast from 3,800 rifles fired simultaneously. As the lines closed with one another, the fighting was close and vicious; the men in Bell’s three Tennessee regiments employed their Colt navy revolvers—they had extra loaded and capped cylinders in their pockets—and in the thick woods the pistols proved more effective than the Union muskets and bayonets. As the battle ebbed and flowed, Wilkin’s 93rd Indiana found its right flank exposed, and, outflanked, retreated toward the crossroads. To support the 93rd, Wilkin committed his reserve, the 9th Minnesota, and suddenly the tide shifted; the 8th Mississippi and 19th Tennessee on Bell’s left broke and headed for the rear. Federal officers, seeing this portion of Bell’s line giving way, tried to exploit the advantage by making a strong rush upon the gray line with fixed bayonets.

Forrest had correctly surmised that the heaviest fighting would take place in this sector and had remained there. Sensing disaster looming, he dismounted his two escort companies and, pistol in hand, led them into the midst of the heaviest fighting where the breach had occurred, where he was soon joined by the courageous Bell. Massed musket volleys and artillery blasts shrouded the field in smoke as the battle escalated to fever pitch. The hard-hit Tennesseans, seeing Forrest in their midst, rallied and, after being reinforced by 280 reserves under Colonel D.M. Wisdom, checked the Union advance. All along the line, heavy fighting continued; Rucker’s troops, on Bell’s right, pushed forward, only to see their advance stymied by Hoge’s determined troops. Forrest rode along his line, shouting out encouragement to his troops. Arriving in the vicinity of the Baldwyn Road, he saw that only two of Morton’s guns, deployed behind the Rebel right, were in action, and he sent orders for more guns to be brought into play.

Artillery Brought to Bear on the Federalist Lines

Forrest was convinced the time had come for the battle to be won or lost. Once again, he rode behind the lines, encouraging his troops, yelling to them that the Yankees were giving way and that one more well-pressed attack would bring victory. Forrest rode over to his young artillerist—Morton had turned 21 on the bloody field at Chickamauga—and told him that another assault would begin in 10 minutes. Morton was to have four of his eight guns double-shotted with canister and limbered. When the bugle sounded, he was to gallop forward as close to the enemy as possible, unlimber his guns into battery, and open fire.

At 4 pm, Morton’s gunners moved their guns to within 200 yards of the Union line, firing charge after charge of double canister into the horrified enemy ranks. Along an 800-yard arc from north of the Baldwyn Road to south of the Guntown Road, the Confederate line advanced, forcing the Union infantry slowly back toward the crossroads. Rucker’s furious attack on the Union center and Bell’s push against its right blasted away the last vestiges of organization on the part of the Federals. As Hoge’s line was pushed back toward the crossroads, men began leaving the line and slipping away. Wilkin on the right tried to rally several retreating regiments, to no avail. He formed a new line farther to the rear, hoping to hold on long enough for the artillery to be hauled away. Simultaneously, Buford, Rucker, and Lyon closed in on the panicky Union forces from all directions, forcing them back to the crossroads where four Federal guns were captured and turned on their former owners. As the gray wave rolled on, the blue line constricted in length from 800 yards to 600, then 400, and finally 300, until the crossroads became jammed with Union soldiers.

“Order Soon Gave Way to Confusion”

Meanwhile, Bouton had arrived with his two brigades and the wagon train. As he approached the Tishimingo Creek bridge, he saw that Waring’s cavalry, having withdrawn, had crossed the bridge and was posted near the intersection of the New Albany and Ripley Roads. Stragglers and skulkers from McMillen’s infantry were making their way to the rear. Bouton called up Captain Franklin Ewing and two companies of the 55th U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI) and sent them across the bridge to join the 72nd Ohio fighting Barteau’s Tennesseans at the bridgehead. For 30 minutes, the fate of Sturgis’s command depended on the Union troops holding Barteau at bay, preventing him from cutting off the escape route of the troops still fighting at the crossroads.

Bouton’s troops west of the creek now deployed, the artillerists unlimbering their guns. After he reinforced the Union troops defending the bridgehead with two battalions of the 4th Iowa Cavalry, McMillen crossed the bridge and gave Bouton instructions. He was to form up the 59th USCI, the remaining eight companies of the 55th USCI, and their two cannons on the ridge separating Dry Creek and the Tishimingo Creek bottom. Bouton was to hold his position as long as possible, while McMillen rode on and formed another line on the next ridge.

Back at the crossroads, disaster was about to strike. Sturgis at this juncture rode over to where he believed the head of the colored brigade would be, and as he was doing so watched in horror as his main line dissolved in several places. “Order soon gave way to confusion,” he later wrote, “and confusion to panic. The army drifted toward the rear and was beyond control. The road became jammed with troops and wagons, and artillery sank into the deep mud and became inextricable. No power could check the panic-stricken mass as it swept toward the rear.” The battle lost, Sturgis gathered up a small escort and made his way across the Tishimingo Creek bridge.

The Confederates closed on the bridgehead, where some of the most savage fighting of the battle took place; Ewing’s black troops, backing up the 72nd Ohio and the 4th Iowa, fought heroically, their wounded refusing to be taken to the rear. Nothing could stem the victorious Confederate tide, however, and the Federals holding the bridgehead finally gave way. Farther to the rear, the bridge over Tishimingo Creek was hopelessly blocked by an overturned wagon and the many wagons that quickly backed up behind it. Fortunately for the Federals, the creek was falling and they crossed upstream from the bridge. Other Union troops forded the creek downstream, and Sturgis’s command, except for Bouton’s men west of the creek, became a panic-stricken mob moving pell-mell northwest up the Ripley Road.

“Keep the Skeer On”

The sun was just above the horizon; Forrest was as relentless in pursuit as he was fierce in battle. As he was fond of saying, he wanted to “keep the skeer on.” With the bridge blocked and the road jammed, Forrest, his escort, and a small group crossed Tishimingo Creek a quarter mile below the bridge. Passing through the cornfields to the Ripley Road-New Albany intersection, the Confederates galloped up the Ripley Road, up the grade to the Ames House ridge where Bouton’s men waited astride the road. Forrest, outnumbered, attacked immediately, only to be repulsed. Sturgis, McMillen, and Grierson forged ahead, crossed Dry Creek, and stopped at Dr. Samuel Agnew’s home, where a straggler line was formed. With Bouton’s line holding to the east, McMillen and his brigade commanders rallied their men and deployed them on both sides of the Ripley Road; out of more than 8,000 troops that Sturgis commanded earlier that morning, only about 1,300 men could now be brought into line.

A sizable number of Confederates, having secured mounts, rode up to join Forrest and his small group assailing Bouton and his colored troops on the Ames House ridge; Confederate artillery moved up as well and opened fire. Bouton, having bought time for the bulk of the Union units to pass through his lines, withdrew and joined the blue troops gathering near the Agnew home. As the sun fell below the horizon, Forrest came up and deployed his men for an attack on the patched-together blue line; artillery boomed, and mounted Confederates stormed forward. For almost an hour, savage, hand-to-hand fighting ensued, much of it between Bouton’s and Forrest’s soldiers. Having gained time for various shattered commands to continue the retreat and for the wagons to roll on, the Federals evacuated Agnew Ridge as darkness fell, crossing Little Dry Creek and continuing up the Ripley Road. The Confederates captured more than a score of wagons, many loaded with rations and provender. Forrest called a halt, allowing the mules and horses to catch their wind and the soldiers to plunder the wagons and get some rest.

The Federal retreat continued. About three miles from Stubbs Farm, the ragged blue column braced for its descent into the boggy Hatchie bottom; troops and wagons moved cautiously into the murky bottom. In minutes, after many teamsters panicked and cut loose their teams and abandoned their wagons, the road became choked and panic spread. Ambulances filled with wounded became mired in the road along with hundreds of other wagons; soldiers on foot sank knee-deep into the mud. As the column inched slowly ahead, Bouton caught up with Sturgis and beseeched him, “General, for God’s sakes, don’t let us give up so.” Distraught, Sturgis replied, “What can we do?” Bouton insisted that his troops, if resupplied with ammunition, would hold Forrest in check on the far side of the bottom while the wagons and artillery were moved ahead to more solid ground; he promised to save the entire column if Sturgis would reinforce him with a white regiment. But Sturgis was too unstrung by the day’s events to give this proposal any consideration. “For God’s sakes,” he told Bouton, “if Mr. Forrest will let me alone, I will let him alone. You have done all you could, and more than was expected of you, and now all you can do is to save yourselves.” The retreat continued toward Ripley.

By 1 am, Forrest had his men back in the saddle and hard on the equipment-littered trail; within two hours they reached the Hatchie bottoms, where they came across the richest haul of all. Despite Bouton’s pleas, Sturgis had ordered everything that could move to proceed to Stubbs Farm and beyond, abandoning the remainder of his wagon train, 23 ambulances, many filled with wounded soldiers, and another 14 guns, all that was left of his original 22 except for four small howitzers that had not been used in the battle. Many Federals, especially Bouton’s colored troops who had suffered heavily bringing up the rear, were overrun in the Hatchie bottoms. The black troops, who had sworn such vengeance on Forrest and his men, hastily tore off the badges marked “Remember Fort Pillow” and lifted their hands in abject surrender. After detailing men to round up the prisoners and collect the spoils, Forrest pushed on.

Retreat from Ripley

Four hours before dawn of June 11, the gray pursuers collided with a rearguard remnant four miles from Ripley and quickly pushed it back upon the town; Sturgis decided to make a stand at Ripley, but when he was notified at 7:30 am that his small remnant was short of weapons and ammunition, he ordered the retreat resumed. The evacuation of Ripley was disorderly; in their haste to get away, the Federals northwest of town abandoned their few remaining vehicles, one cannon, three caissons, and two ambulances. When they were gone, local citizens gathered up Union dead and wounded.

Beyond Ripley, Forrest turned the main column over to Buford and, knowing the area, swung onto a roundabout adjoining road with Bell’s men, hoping to cut the Federals off at Salem. As he approached Salem, however, Forrest’s horse, King Phillip, stumbled and fell. Striking his head, the exhausted Forrest lost consciousness and slept for a solid hour. Before Forrest arrived in late afternoon, the blue column cleared Salem, after its rear guard had been savaged by Buford. Forrest called off the chase at that point, turning back to scour the woods for more prisoners, gather up more spoils, and give his men and animals some much-needed rest. Unaware that they were no longer being pursued, Sturgis’s command pushed on as darkness fell and rain began to fall. At 8 pm on June 12, Sturgis’s van reached Collierville, Tennessee, 26 miles east of Memphis. After being routed from Brice’s Cross Roads, the survivors had marched 90 miles in 40 hours; worn out and exhausted, they dropped to the ground in a sodden heap.

Forrest’s Greatest Victory

The Battle of Brice’s Cross Roads was over—many would call it Forrest’s greatest victory—and for Sturgis the recriminations began. Back in Memphis, with rumors swirling that he must have been drunk during the disaster, Sturgis tried to cast a better light on things. He claimed that his army had fought nobly but had been forced to yield to overwhelming numbers; despite reports to the contrary, he insisted that Forrest’s forces had numbered between 15,000 and 20,000 men. Sturgis had suffered 223 men killed in the battle, half of them from the black brigades; 394 wounded; and 1,623 missing, the vast majority of whom had been captured. The Confederates, at a cost of 96 killed and 396 wounded, had captured almost the entire Union train of wagons and ambulances, 16 cannon, 28 limbers, 15 caissons, hundreds of rounds of artillery ammunition, 1,500 rifles, and 300,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition.

A disappointed Sherman wondered: “Forrest has only his cavalry. I cannot understand how he could defeat Sturgis with 8,000 men.” Sherman did give Sturgis credit for having achieved his chief objective, which had been to hold Forrest in Mississippi away from Sherman’s supply lines. Adamant that Forrest must be kept busy west of the Tennessee River, Sherman made plans for another—better-led and stronger— incursion into northern Mississippi, this time using scorched-earth tactics. Maj. Gen. A.J. Smith’s three veteran divisions would now be employed to keep Forrest busy in Mississippi. Brig. Gen. Joseph Mower would take part in the mission as well, and Sherman took the unprecedented step of offering him a promotion to major general if Forrest was killed during the incursion. “I will order them to make up a force and go out and follow Forrest to the death,” Sherman wrote, “if it costs 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee till Forrest is dead.” Samuel Sturgis would have agreed completely with that sentiment.

This account differs from those that I had read in years past…but it was more detailed in troop movements. General Forrest had many gifts, among which was to get into the head of the enemy, analyze the weather and the terrain quickly, and then commit his forces at just the right time. He did not seem to care what numbers he faced, but cared for the men and mounts, resting them when possibly. He understood rest and effort. Gen. Sturgis needed more understanding of these elements…did he rely on the new 7 shot carbines, superior artillery, and reinforcements of wagons, ambulances, etc.?