By Lawrence Weber

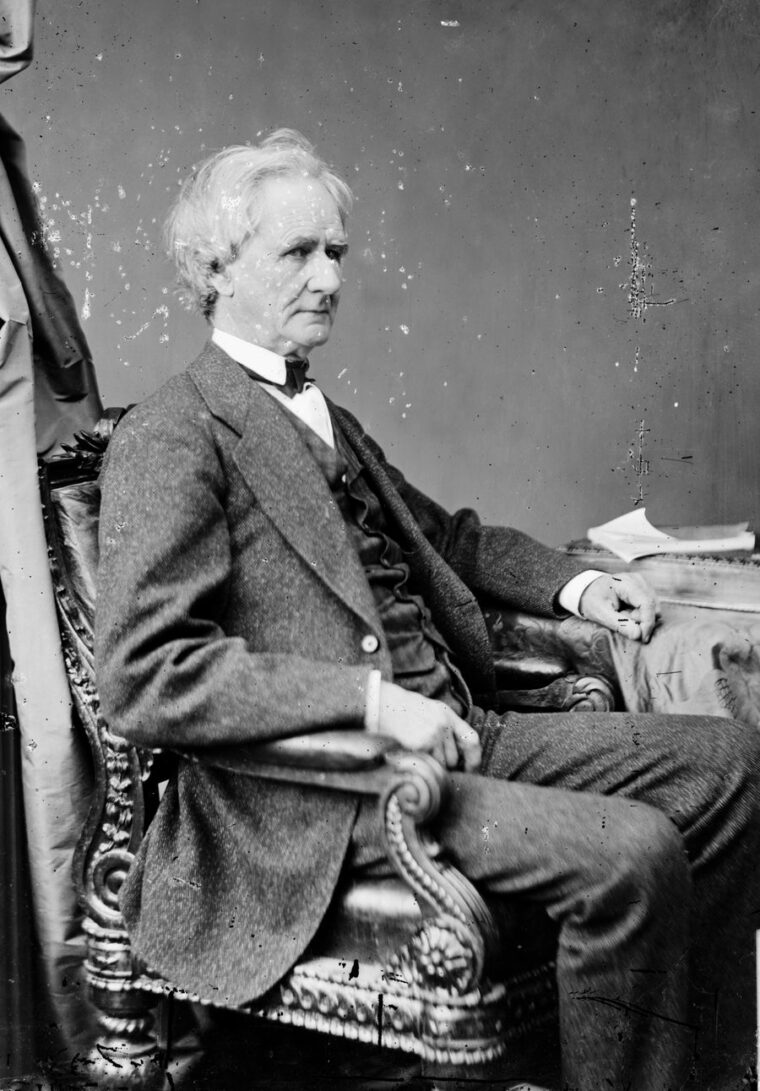

In the spring of 1861, a group of influential northern men and women, led by Unitarian minister Henry Whitney Bellows and social reformer Dorothea Dix, met in New York City to discuss the formation of a sanitary commission, modeled after the British Sanitary Commission established during the Crimean War, to provide relief to sick and wounded soldiers in the Union Army. At the meeting, which took place on April 25, various topics were discussed, including how best to carry out much-needed sanitation and relief work on a grand scale for the benefit of Union soldiers spread throughout the country. By the conclusion of the meeting, the group had laid the foundation for a provisional sanitary commission to be called the Women’s Central Association of Relief for Sick and Wounded in the Army, or WCAR for short.

Creating the WCAR

The goal of the WCAR was to organize and implement a wide-reaching group of women who would provide humanitarian aid to wounded and sick Union soldiers. One of the most important members of the WCAR was Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree. Blackwell’s knowledge of medicine was critically important for training new nurses who would eventually travel to army camps to tend the sick and wounded. The goals were noble and humane, but implementing them successfully would prove to be daunting. To be effective, the provisional sanitary commission would need to be assisted by the national government. Bellows felt that it was imperative to go to Washington, D.C., to examine the existing system of medical relief already established by the government. He set off with a small group of doctors, dubbed the Sanitary Delegation, to investigate the government’s ability to respond to the Army’s mushrooming health and relief needs.

Bellows discovered that the government was woefully unprepared for the great national crisis that was already occurring; an extensive sanitary and relief system overhaul was needed immediately. Bellows’s delegation consulted with military and hospital departments for ways to supplement the all-too-apparent governmental deficiencies. They sent letters to the surgeon general of the United States Army, Colonel Thomas Lawson, and to Secretary of War Simon Cameron, requesting that a permanent sanitary commission be established.

Pushing the WCAR Through

Cameron did not reply immediately, and the letter sent to Lawson failed to reach him before the surgeon general died suddenly on May 15 of apoplexy. The letter made its way to the desk of interim Surgeon General Robert C. Wood instead. Wood, the son-in-law to former president Zachary Taylor and the brother-in-law of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, found the letter persuasive and wrote to Cameron endorsing the group’s request. “The Medical Bureau would, in my judgment, derive important and useful aid from the counsels and well-directed efforts of an intelligent and scientific Commission,” Wood advised.

Cameron waited until a new permanent surgeon general was appointed before making a decision. After President Abraham Lincoln chose Dr. Clement Finley to replace the deceased Lawson, Cameron presented Finley with Bellows’s suggestion for a sanitary commission. Meanwhile, Bellows fired off another letter to Cameron outlining the creation of a formally recognized United States sanitary commission. The letter highlighted the goals of the Sanitary Commission, with specific attention paid to the prevention of infection and disease among the sick and wounded.

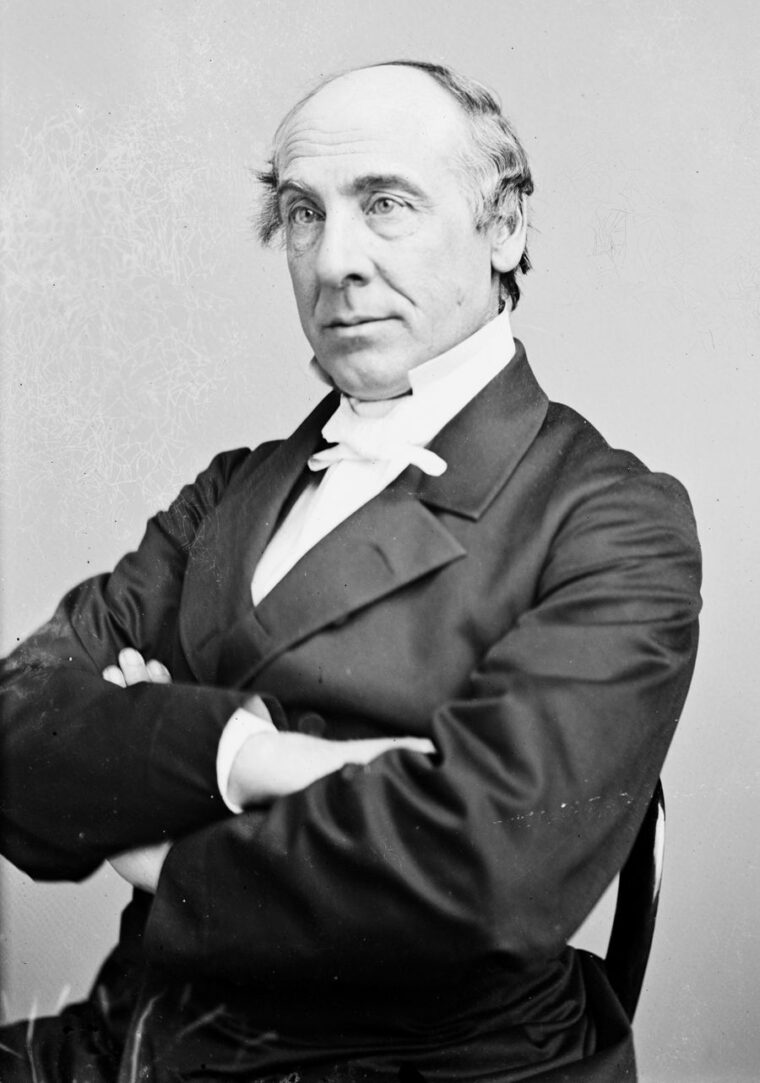

After careful consideration of the letters and with the new surgeon general’s blessings, Cameron drafted a resolution on June 9 endorsing the creation of the United States Sanitary Commission. He sent the resolution to President Lincoln for approval, and on June 18, Lincoln signed the necessary paperwork establishing the United States Sanitary Commission. As a reward for his hard work, Bellows was named president of the commission. Other members included Robert C. Wood; George Templeton Strong, the famous Civil War diarist who became the commission’s treasurer; renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who had designed New York City’s Central Park; and Dorothea Dix, who was appointed superintendent of women nurses.

The Search for Recruits and Sponsors

The Sanitary Commission went to work immediately, attempting to increase its membership across the Union. In its first year, the commission’s membership grew almost exponentially. By 1863, there were more than 500 branches working under the umbrella of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was divided into three departments: the Department of Preventive Service, sometimes called the Department of Inspection; the Department of General Relief; and the Department of Special Relief. The Preventive Service Department was responsible for the inspection of volunteer forces, with specific attention paid to the area of disease, field conditions, and proper medical care. Special focus was placed on the soldiers’ diet, which was often high in calories but low on nutrition. Hardtack, salted pork, coffee, crackers, and preserved beef were staples of the soldiers’ daily fare. Conspicuously missing were fresh fruits and vegetables, which were hard to acquire. Food was often fried or undercooked, causing many soldiers to become ill from the poorly prepared, non-nutritious foods.

Once the Sanitary Commission was sufficiently organized and staffed, volunteers set out at once to take their message to the soldiers. One of the best ways the Sanitary Commission was able to get out its message was through the printed media. The commission distributed 18 short treatises written by eminent medical men to regimental surgeons and commanding officers. Since the Medical Department had not issued any such treatises to them, the little books were of inestimable value. Sanitary Commission circulars, pamphlets and broadsides were also critically important in keeping the public informed and supportive. To raise money, publications such as the Sanitary Commission Bulletin and Drum Beats were sold for profit, and agents traveled across the country lecturing and fund-raising.

First Battle, First Challenges

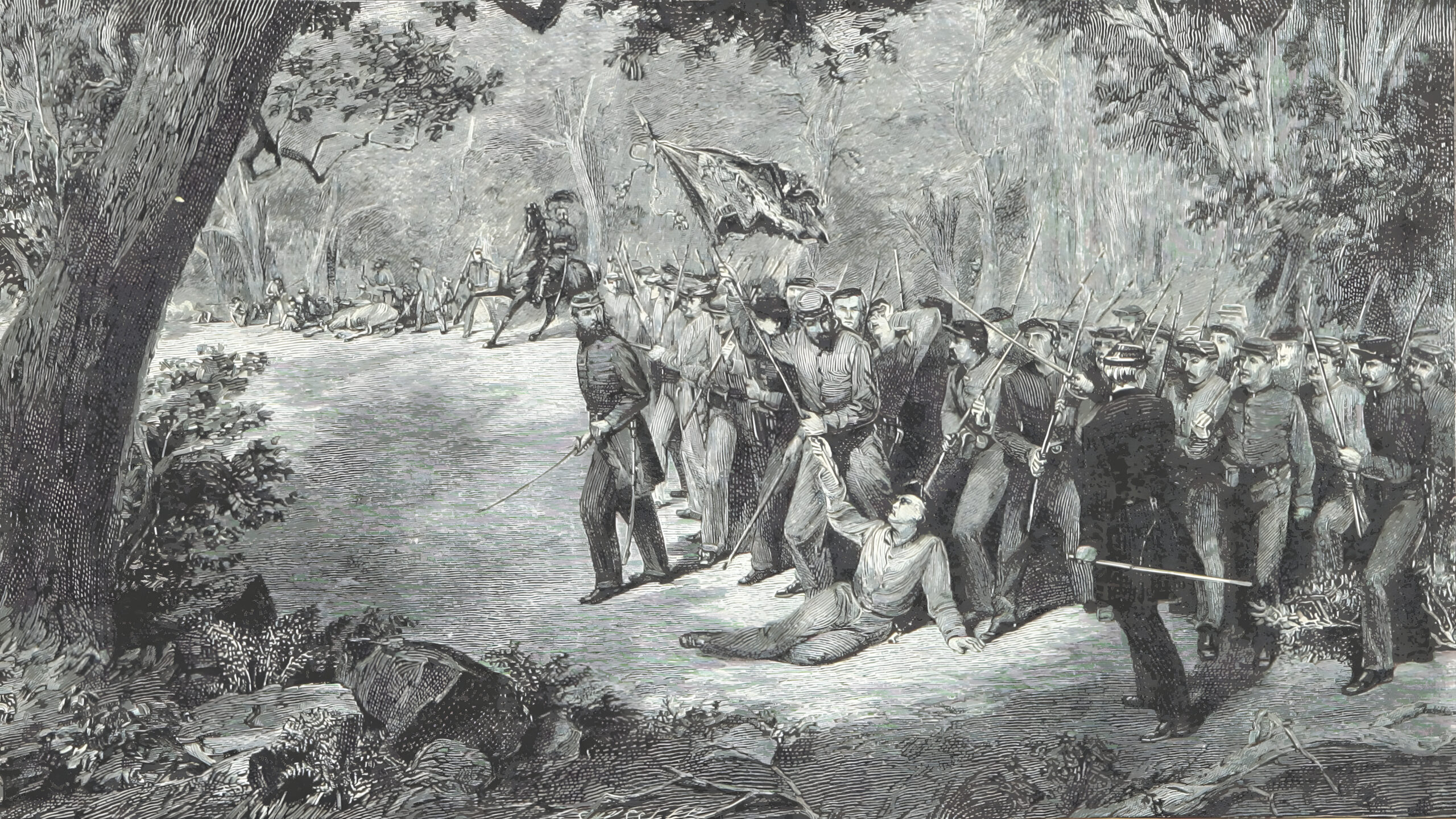

The ideas contained in the treatises were put to the test in July 1861, after the First Battle of Bull Run. There was no systematic method of gathering sick and wounded men from the battlefield to the field hospitals. The soldiers who could do so simply straggled in disarray, away from the battle, in search of help. When the Sanitary Commission investigated some of the reasons for the Union Army’s failure at First Bull Run, they discovered that many of the soldiers were too fatigued and hungry to fight properly.

To prevent the mistakes of First Bull Run from happening again, the Sanitary Commission submitted an article, written by Dr. William H. Van Buren, to Harper’s Weekly, which had a circulation of over 200,000 readers. The piece, published on August 24, roughly a month after the battle, was entitled “Rules for Preserving the Health of the Soldier.” The article, like the earlier treatises, included a great deal of useful information for the soldiers to consider. Included in the article were tips on food preparation (frying meat in camp was unsafe and wasteful), the use of spirits (men who used alcohol regularly were the first to fail when strength and endurance were required), campsite selection, and proper grooming habits (hair and beard should be closely cropped). There was also advice on the proper marching pace (90 to 100 steps to the minute), tent spacing (tents should be placed as far from each other as possible, and never less than two paces), and tips on the treatment of wounded men (it was not always necessary to extract a bullet; in fact, more harm might be done in attempts to remove them). The article succeeded in spreading the Sanitary Commission’s message to a wider audience.

Adapting to Challenges

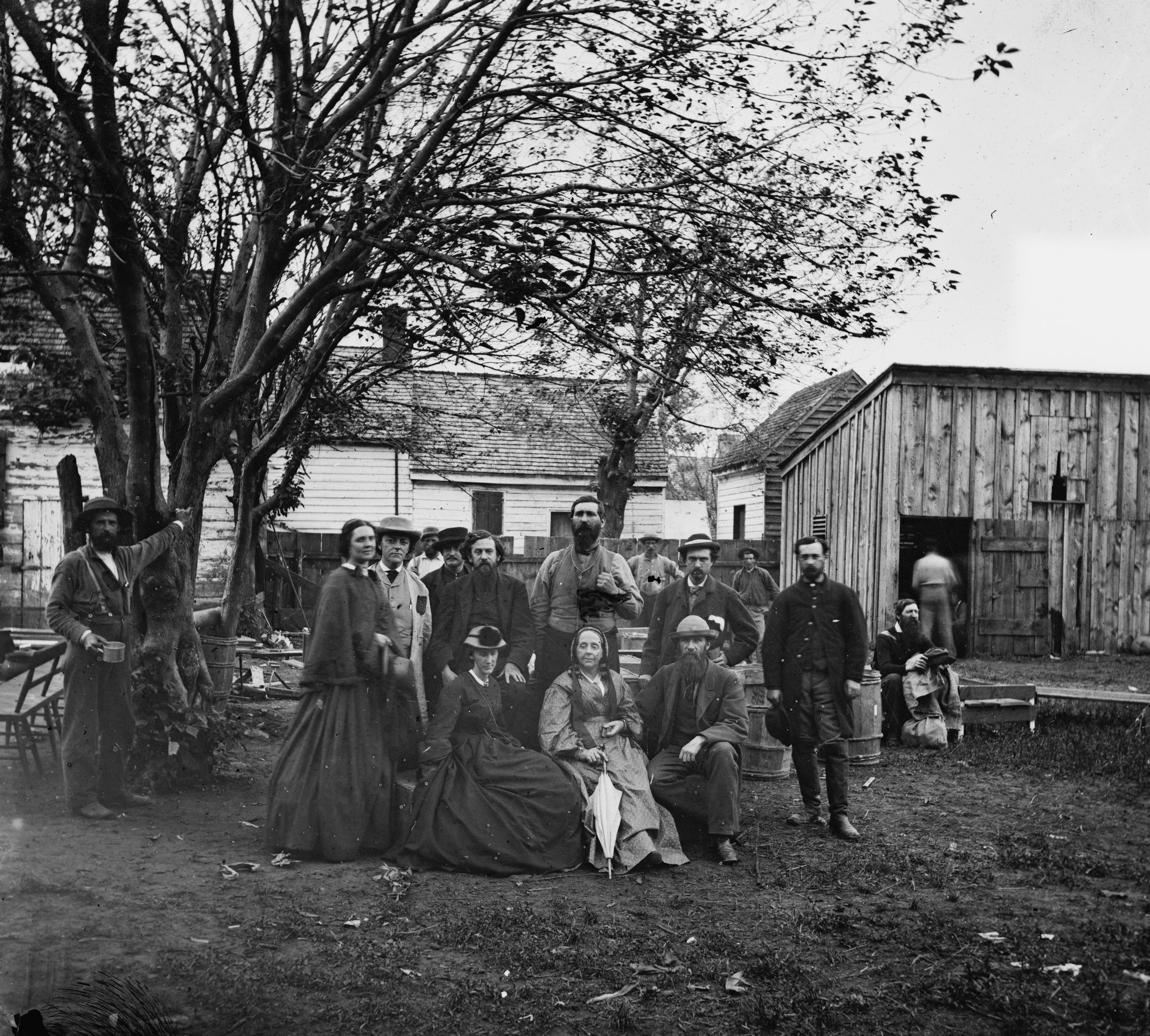

As the war continued, the Sanitary Commission became more efficient. Dressing stations were established on the outskirts of a battlefield and staffed with assistant surgeons, stretcher bearers, and nurses. The staff of a typical dressing station came equipped with bandages, whiskey, brandy, opium pills, and morphine for injured soldiers. Soldiers who were treated at dressing stations but still in need of advanced care walked to field hospitals if their injuries allowed. Soldiers who could not transport themselves to field hospitals were taken by ambulance—provided there were ambulances.

If a soldier survived surgery or treatment in a field hospital, he still faced mortal danger from surgical fevers triggered by infection. Blood poisoning, pneumonia, or erysipelas (a subcutaneous skin infection) could rapidly lead to death. Perhaps the most famous example of this scenario came following the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, when Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson died from complications brought on by infection after his left arm was amputated.

Upon reaching a permanent hospital, the wounded soldier would be placed under the care of nurses. One of the most famous Sanitary Commission nurses was Louisa May Alcott, famed author of Little Women. In 1863, Alcott published a book entitled Hospital Sketches containing reflections on her life as a Sanitary Commission nurse. Alcott described a common scene: “To me, the saddest sight I saw in that sad place, was the spectacle of a grey-haired father, sitting hour after hour by his son, dying from the poison of his wound,” she wrote. “The old father, hale and hearty; the young son, past all help, though one could scarcely believe it; for the subtle fever, burning his strength away, flushed his cheeks with color, filled his eyes with luster, and lent a mournful mockery of health to face and figure. When the son slept, the father watched him, and though no feature of his grave countenance changed, the rough hand, smoothing the lock of hair upon the pillow, the bowed attitude of the grey head, were more pathetic than the loudest lamentations.” After his son died, the grieving father told Alcott and the other nurses: “My boy couldn’t have been better cared for if he’d been at home; and God will reward you for it, though I can’t.”

Expanding the Sanitary Commission

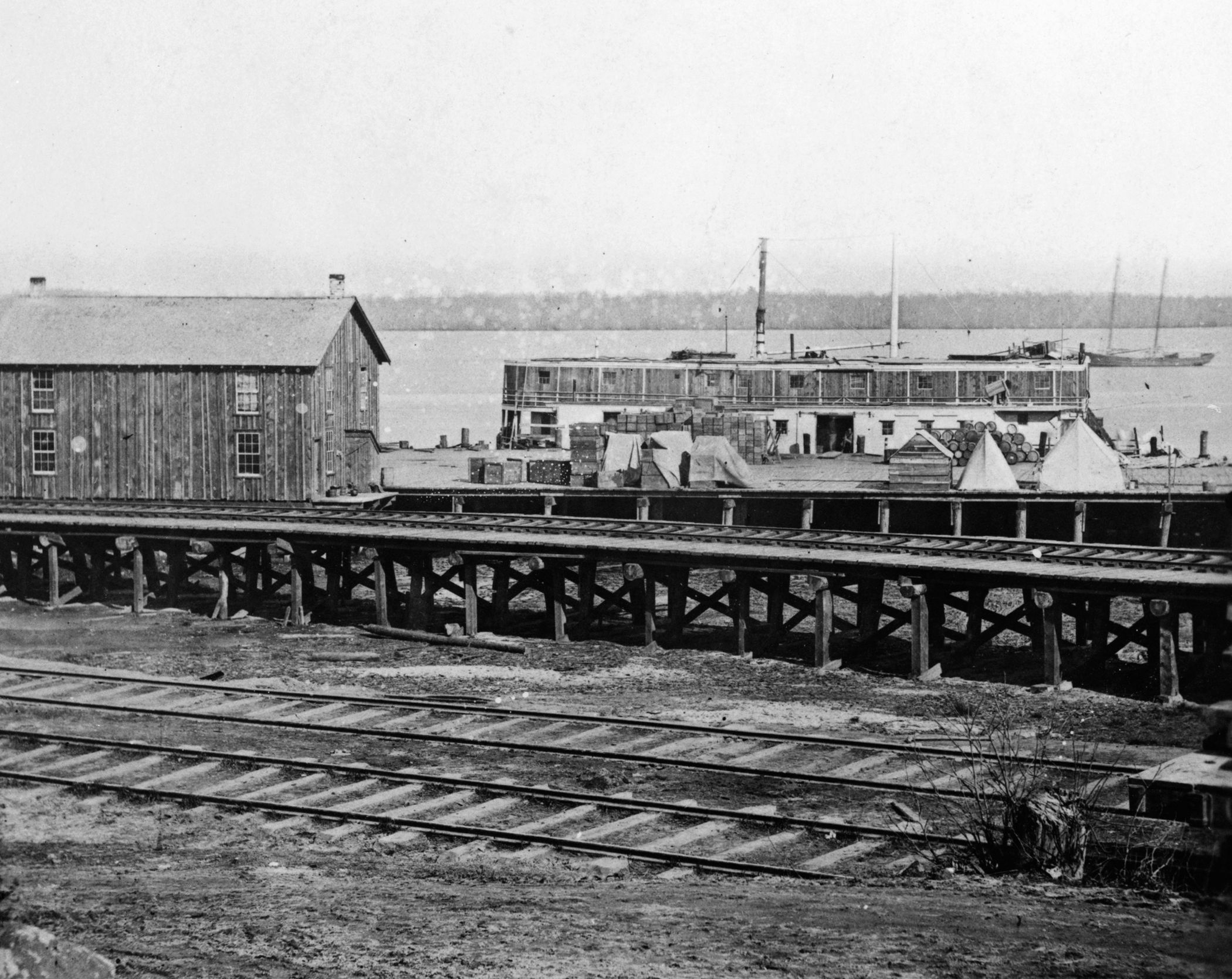

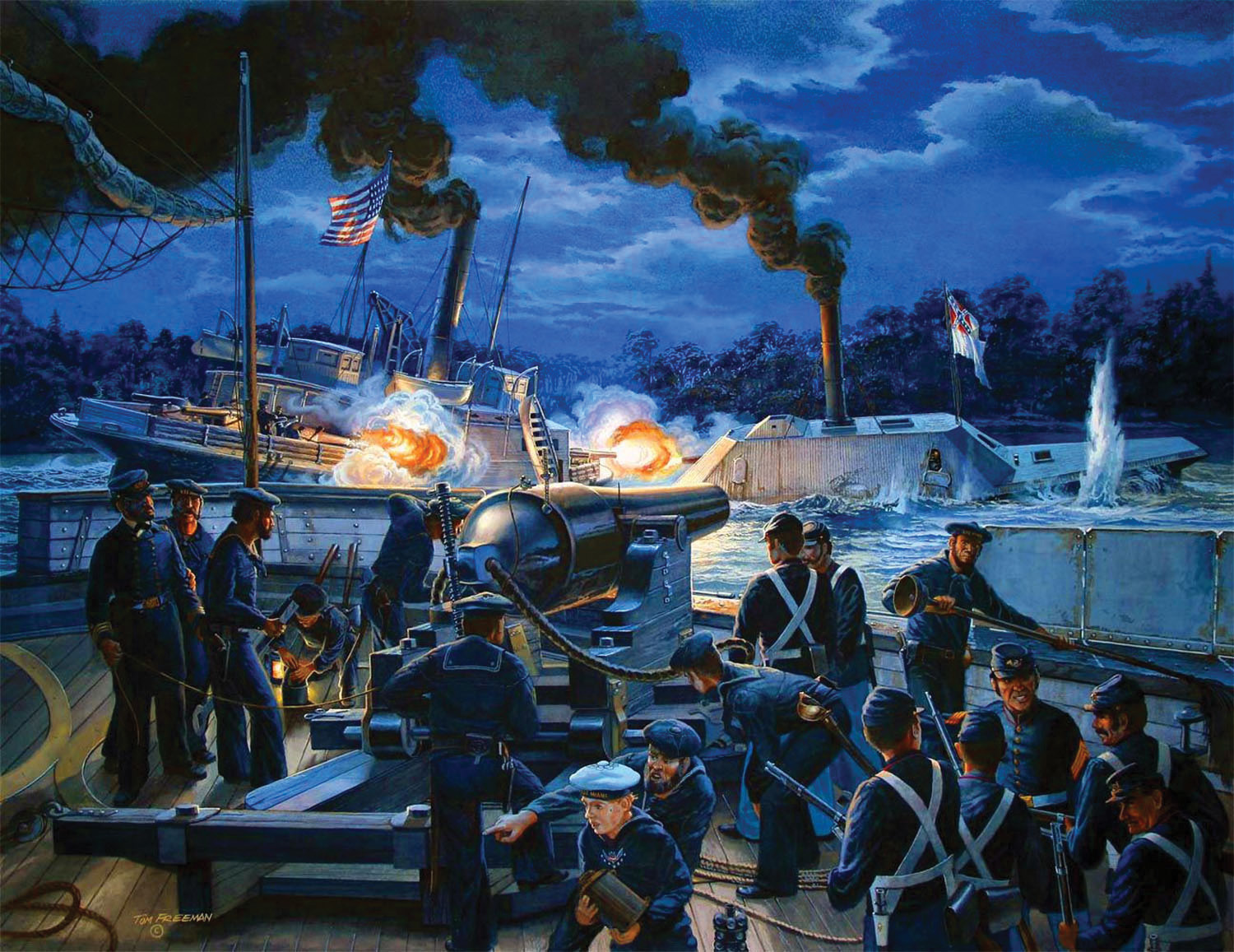

By 1862, the Sanitary Commission’s role had grown as the scope and nature of the war had grown. The Peninsula campaign of 1862 witnessed the launch of one of the first Union hospital ships during the Civil War, Daniel Webster No. 1, which was able to support some 1,000 sick and wounded soldiers. Most hospital ships were outfitted and staffed by the Sanitary Commission. The objective of the hospital ships was to transport injured soldiers from the war zone as quickly as possible to safe locations where they had access to better medical treatment. During the campaign, some 19 hospital ships were assigned to the Virginia peninsula. It was hard work, but every patient on the ships had a good place to sleep and something hot to eat, and the sickest were given every medical essential.

As 1862 moved along, the Sanitary Commission was severely tested at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. The commission responded admirably and even seemed to outperform the government’s Army Medical Department, which was slow to respond to battlefield needs and often less efficient. That year saw another important addition to the Sanitary Commission’s already critical work: the creation of the Hospital Directory, an agency that provided information to the general public about the location of sick and wounded soldiers in the army’s general hospitals.

The Creation of the Hospital Directory

Established because of the tremendous influx of letters from families inquiring about the status of their loved ones, the Hospital Directory was headed by John Bowen. Under Bowen’s leadership, the directory recorded information on more than one million soldiers. The information was sent to the directory’s four main offices in Washington, Louisville, Philadelphia, and New York, where it was used to answer questions about missing soldiers and offer comfort and closure to families in despair.

The Hospital Directory also served as a data- gathering center, recording hospital and patient information that was used, in turn, by the Statistical Bureau for the evaluation of medical performance. The Statistical Bureau compiled data on the sanitary conditions of Army life through questionnaires that contained some 190 questions on such topics as camp soil, drainage, quality of available food, water supply, and the background of medical personnel. Through the careful evaluation of the questionnaires, the Sanitary Commission could understand more fully the dangers and complexities of camp life and, consequently, tweak and improve its own relief work.

Acceleration of the War

The year 1863 was especially tumultuous. The battles that took place that year were some of the largest and most consequential of the entire war—Chancellorsville, Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga. The Sanitary Commission was there for all of them. At Gettysburg, where the carnage was perhaps the most gruesome (approximately 22,000 soldiers from both sides needed medical attention after the battle), Sanitary Commission volunteers worked without rest. When the work of tending to sick and wounded was done, the surgeons in charge of the general hospitals near Gettysburg took the time to write the Sanitary Commission inspector at Gettysburg a letter expressing gratitude “at the manner in which the affairs of the United States Sanitary Commission have been managed since the late battle. The supplementary articles for the sick and wounded have been abundant, comprising every requisite which the exigency demanded, and which nothing but a well-regulated system, with much experience and forethought, could have secured.”

In 1864 came some of the worst carnage of the war. In such places like the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Atlanta, and Nashville, the Sanitary Commission went to offer relief. The commission extended its Department of Special Relief to include the Army and Navy Claim Agency, based in Washington, which was designed to assist soldiers and their families in filling out the proper government forms to obtain back pay, pensions, bounties, and prize money. Many soldiers in the hospital, with families sorely in need of help, were unable to obtain the money that was due them or that was so tied up in red tape that it was beyond their power to collect. Agents of the commission, authorized by the Paymaster’s Department, helped remove such difficulties. In Stanton Hospital alone, the back pay of 56 men, amounting to $3,008.96, was procured in a single week.

Maintaining a Presence

When the Civil War ended in April 1865, the work of the Sanitary Commission continued. The commission worked to negotiate the return of prisoners of war, helped to smooth the process of discharging Union soldiers, and continued to care for hospitalized soldiers. The commission also continued the good work of the Hospital Directory by reuniting soldiers with their families whenever they could and by offering comfort and closure to families who had lost loved ones. Not until October 1, 1865, did the commission’s active relief work officially end. And though it is true that more soldiers died during the Civil War from infection and disease than from bullet wounds, the numbers surely would have been higher without the tireless contributions of the United States Sanitary Commission.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments