By Gustav Person

In the summer of 1814, the residents of the District of Columbia and surrounding counties in Maryland and Virginia had considerable cause for concern. It was the third year of the War of 1812 between the nascent United States and its former colonial ruler, Great Britain. In August, the British began assembling a large task force off the Maryland coast under the overall command of Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane. An experienced sea dog, Cochrane had been sent to America with explicit instructions to chastise severely the upstart nation, which, as one British naval leader put it, “had declared war against us when our hands were full in Europe and who, by their maritime success, had astonished themselves as much as they had surprised us.” Cochrane’s raid was intended specifically to avenge the American burning of Upper Canada’s capital at York (present-day Toronto).

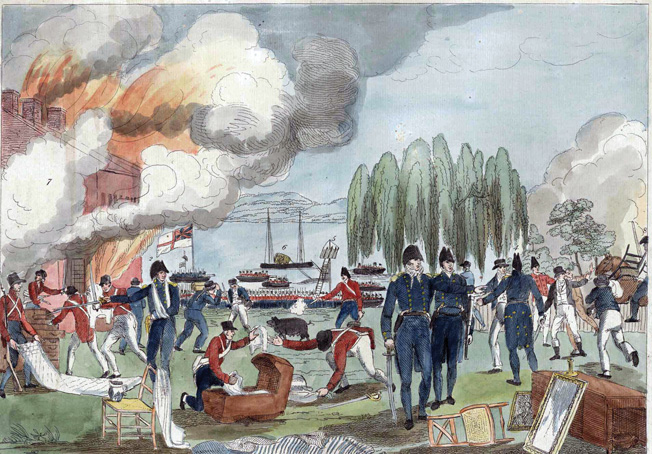

Cochrane assigned Rear Admiral George Cockburn to command the strike on the American capital in Washington. Cockburn had already had considerable success raiding the Chesapeake Bay area. In April 1813, he attacked and burned Frenchtown, Maryland. The next month, he burned the towns of Havre de Grace, Georgetown, and Fredericktown, all in the upper reaches of the Chesapeake. Cockburn then moved on to Principio, a munitions-manufacturing town in northeastern Maryland, destroying a cannon foundry, and for 12 days the British roamed freely on American soil. A furious member of Congress noted that “Cockburn’s name was on every tongue, with various particulars of his incredibly coarse and blackguard misconduct.”

Rear Admiral George Cockburn’s British forces burn and plunder Havre de Grace, Maryland, in May 1813.

“Bladensburg Races”

On August 19, 1814, Cockburn landed Maj. Gen. Robert Ross and 4,370 veteran troops, fresh from their successes against French forces in Spain and Portugal, along the Patuxent River at Benedict, Maryland. The British then made a five-day march through heat that frequently started the day at 98 degrees. To check them, 7,000 American militia troops under Brig. Gen. William H. Winder were hurried into battle near Bladensburg, Maryland, a few miles northeast of Washington, on August 24. The green American troops quickly broke under the disciplined British attack and fled from the field.

The American flight was so precipitous and headlong that it quickly became known as the “Bladensburg Races.” A few hours later, the British advanced into the District of Columbia and put to the torch many public buildings, including the Capitol and the executive mansion. The Washington Navy Yard was burned by its commander rather than let it fall into enemy hands. That night, the British camped on Capitol Hill. In all, the British plunder included 540 barrels of powder, 206 cannons, and 100,000 rounds of cartridges. The next day the invaders departed in the midst of a violent tornado, one of several that struck the Washington area, seemingly in celestial anger at the British effrontery.

Beginning on September 11, Cochrane struck Baltimore with a naval flotilla of 50 ships and a land force under Ross. They chose to punish Baltimore first for its role as the center of a large-scale American privateering campaign. The British were repelled by local forces consisting of regular troops and local volunteers, and a massive rocket and mortar attack against Fort McHenry barely made a dent. Francis Scott Key, a Georgetown attorney, was in Baltimore during the attempted invasion and witnessed the all-night bombardment. On the morning of September 14, he saw the fort’s huge flag still flying above the fort and was inspired to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Expedition up the Potomac

While Ross entered the Patuxent River to start his epic overland march on Washington, one-legged Captain James Alexander Gordon, not yet 30 years old, set out on an equally rigorous waterborne expedition against the American capital. The ambitious and audacious river voyage was aimed at an inland objective 100 miles from the open ocean off the Virginia capes. Many of the officers and seamen under Gordon’s command had arrived in the Chesapeake mere days earlier, having shipped on June 2 from the Mediterranean with no home leave after long tours of duty. Gordon’s force consisted of some 1,000 weary sailors, and he worried that they were “by no means fit to cope with the picked men of America.”

The squadron comprised Gordon’s flagship, HMS Sea Horse; the 38-gun frigate HMS Euryalus, under Captain Charles Napier (Gordon’s second in command); the 36-gun frigate HMS Devastation, commanded by Captain Thomas Alexander; three bomb vessels—HMS Aetna (Captain Richard Kenah), HMS Meteor (Captain Samuel Roberts), and HMS Erebus (Captain David E. Bartholomew)—the rocket ship HMS Anna Maria, and a dispatch boat. In all, Gordon counted a total of 173 guns in his squadron.

The trip up the Potomac River included many hazards. Previously, the 44-gun American frigate, USS President, had come downriver from Washington in 42 days, her guns taken off and loaded in small boats in order to float her successfully over the Potomac’s extensive shoals. A British frigate had already abandoned, as impossible, similar efforts to effect an upriver passage. If he managed to make it that far, Gordon still had to successfully pass Fort Warburton, six miles below Alexandria and 12 miles below Washington on the Maryland shore.

The British invading fleet entered the Potomac on August 17, the same day that the main British force entered the Patuxent River. The second day brought Gordon above the Wicomico River to the Kettle Bottoms, a series of intricate shoals “composed of oyster banks of various dimensions, some not larger than a boat with passages between them.” Admiralty charts dating back to 1776 were little help, said Gordon, since “none of the pilots knew exactly where they lie.”

The squadron weighed anchor and proceeded with great caution behind several small warning boats rowed abreast of each other. Despite this maneuver, Sea Horse grounded on a sand bank. Anchoring, the frigate sent boats and hawsers to pull her off. No one could tell where she had hung up. She had plenty of water astern, ahead, and all around, but she could not move. A diver later found, to the astonishment of all, that an oyster bank no larger than a small boat was under Sea Horse’s keel. After much hard heaving, the frigate was floated off. The remainder of the frigate’s crew spent the day gathering provisions from shore. Several other vessels went aground as well, but each got off with more ease.

Finally, on August 19, with a favorable breeze, the British squadron cleared the Kettle Bottoms, only to fall victim to variable tides that further hindered the expedition’s progress. Gordon anchored off Maryland Point on August 24, the same day that Ross and Cockburn completed their 50-mile overland thrust and burned Washington. Gordon’s officers could plainly see the reflection of the fires from Washington in the skies above. Believing that the flames marked the British withdrawal after the capture of the American capital—Cochrane’s stated objective—the Potomac squadron decided nonetheless to proceed toward Washington on its own.

Captain Napier noted the progress. “The enemy gave us no trouble, either with fire vessels or with light troops who might have been stationed in such a manner on both banks of the river as to have rendered the laying out of the anchors totally impossible,” he wrote. “But considering we were several hundred miles in the interior of the enemy’s country, the utmost precaution was necessary to provide against any unforeseen attack.” No further plundering was permitted; the strictest discipline was enforced.

Weighing anchor early on August 25, the squadron was beset by strong winds and squalls. Napier reported that “the squall thickened at a short distance, roaring in a most awful manner and appearing like a tremendous surf.” Ever troublesome, Sea Horse sprung her mizzenmast and Meteor, lying on a bank, was nearly blown over and brought up in deep water. Euryalus lost her bowsprit, requiring that a new one be fabricated out of a topmast.

About 5 pm on August 26, George Washington’s old home at Mount Vernon appeared in view. The British ships lowered their foretopsails in courtly salute as they passed the “gentleman’s residence” and the ships’ bands played “Washington’s March.”

Seizing Alexandria

The night before the fiasco at Bladensburg, General Winder had ordered Captain Samuel T. Dyson, the commanding officer at Fort Warburton, in the event of “being taken in the rear of the fort by the enemy, to blow up the fort and retire across the river” with its 57-man garrison. Built in 1808-1809 on the Maryland shore at Digges Point alongside Piscataway Creek, the fort, later renamed Fort Washington, contained a considerable arsenal of heavy ordnance. The fortification included a water battery and rear battery and an octagonal brick blockhouse two stories high.

Anchoring his squadron just outside the fort’s range, Gordon sent his bomb vessels to positions where they could cover the frigates in the next day’s projected daylight attack. Dyson, however, either misunderstood Winder’s orders or was simply a coward. The British bomb vessels fired a few preparatory shells, at which point Dyson blew up the magazine, which contained 3,000 pounds of black powder, and abandoned the fort without firing a single shot, leaving the British at a loss to account for such an extraordinary step. The fort held a good position, and its capture would have cost the British at least 50 men or more, had it been properly defended.

Dyson also managed to spike a large number of guns before his withdrawal, including two 32-pounders and eight 24-pounders. Later that year, an Army court-martial found Dyson guilty of all charges and specifications, except for drunkenness (which might at least have explained, if not necessarily excused, his unvalorous actions). He was summarily dismissed from the service.

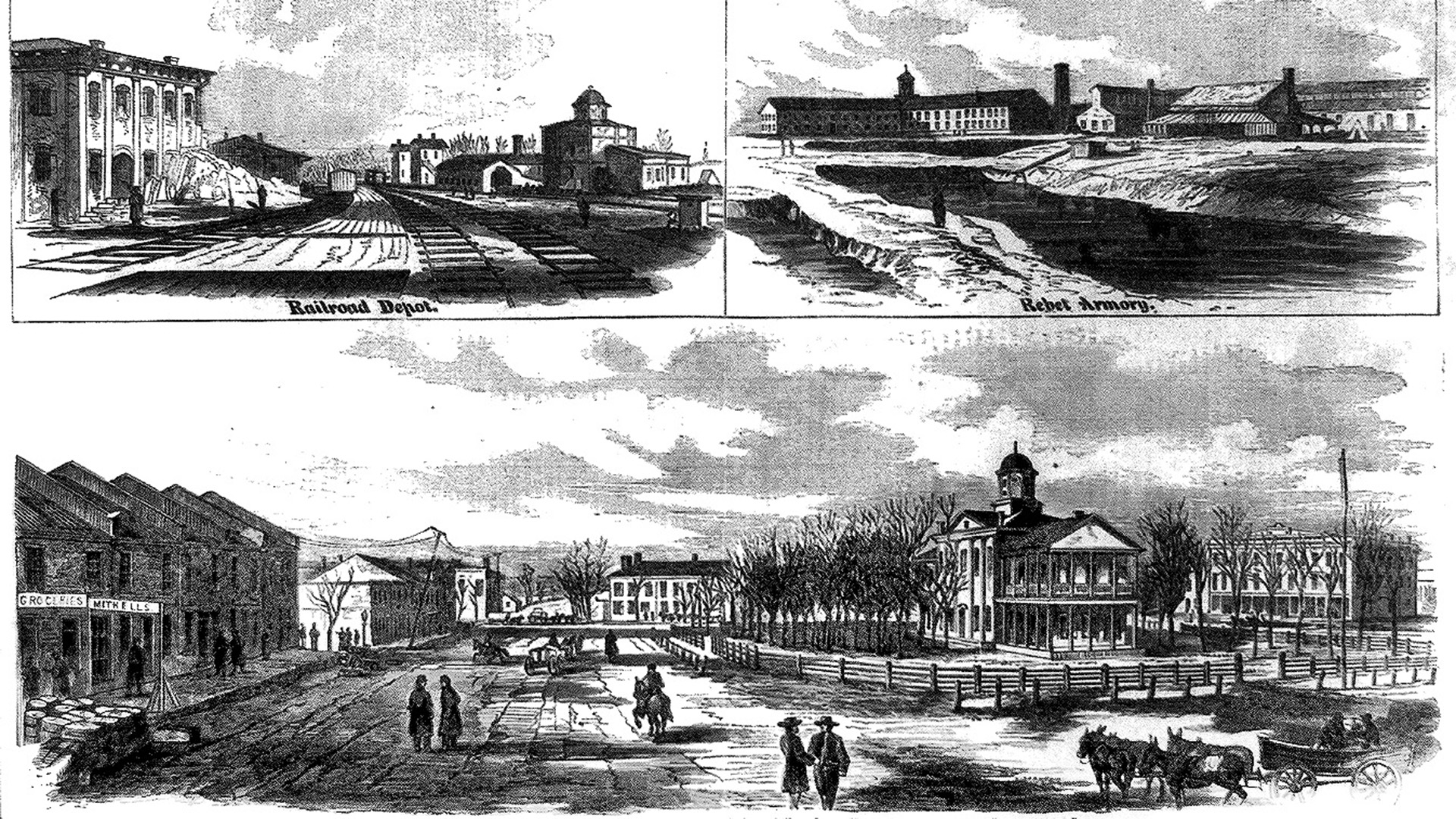

The British continued their journey upriver toward Alexandria, which earlier had been stripped of troops in the hopes of successfully defending Washington. At 10 am on Sunday, August 28, Mayor Charles Simms and a group of residents rowed downriver in the direction of the approaching British task force, displaying a flag of truce. Behind them, on the opposite bank, the Washington Navy Yard continued to burn, as if to remind them of the penalty they would incur if they did not surrender. They boarded Gordon’s flagship, Sea Horse, to ask what fate awaited them. Alexandria’s Common Council had already decided to capitulate, on terms that gave Gordon the kind of tribute Ross had hoped fruitlessly to obtain from Washington.

On the following day, an officer from Sea Horse delivered to the mayor Gordon’s seven written conditions for sparing the city and its inhabitants. The list demanded the immediate surrender of all naval and ordnance stores, as well as the possession of any ships in the vicinity. Vessels sunk a week earlier also had to be surrendered, although only one could be raised and reconditioned. The British plundered warehouses along the river bank of their agricultural produce for the next few days, stuffing 21 prize ships with looted cargo. All told, they stashed away 16,000 barrels of flour, 1,000 hogsheads of tobacco, 150 bales of cotton, and some $5,000 worth of wine, coffee, sugar, and cigars. Even so, the British had to leave behind another 200,000 barrels of produce for want of transport. Meanwhile, the local residents watched indignantly.

Contrary winds delaying his departure, Gordon received bad news from Captain Henry L. Baker, who had sailed the 18-gun brig HMS Fairy upriver with dispatches from Admiral Cochrane. Baker reported that the Americans had already begun building artillery batteries along the Potomac to harass the British squadron’s downriver withdrawal. Baker could speak from personal experience—his vessel had been exposed to American gunfire as he sailed upriver. Baker presented dispatches from Cochrane ordering Gordon to return to the Chesapeake as soon as possible.

“650 Picked Men”

While the British languished at Alexandria, the American government acted to head them off. Having returned to the capital after the British departure, President James Madison immediately named Secretary of State James Monroe as acting secretary of war and commander of the 10th Military District, after the unexpected resignation of the incumbent, General John Armstrong. Monroe’s first move was to try to trap the British at Alexandria. To accomplish this, he sent some Virginia militia, several District of Columbia units anxious to redeem themselves after Bladensburg, and senior Navy Commodore John W. Rodgers’s “650 picked men” just summoned from Baltimore. Secretary of the Navy William Jones (a sea captain and Philadelphia ship owner) and Commodore Rodgers (who had fired the war’s first shot with his own hand on the flagship USS President) had begun to work out a strategy to counter Gordon’s expedition.

Rodgers improvised a force of fireships at the Washington Navy Yard, and with the 650 picked seamen and marines from the USS Essex took them down to Alexandria to attack the British from the rear. Meanwhile, Jones met with Brig. Gen. John P. Hungerford, who commanded the 14th Virginia Militia Brigade from the Northern Neck, and Captain David Porter, U.S. Navy, on Shooter’s Hill outside Alexandria to plan the next countermoves. Members of the Virginia militia had formed up quickly in their home districts and then arrived on August 23 at the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, where they were issued short rifles. The next morning, the militiamen embarked in flour boats to travel down the Potomac to Alexandria.

Porter, who had managed to assemble a force totaling about 1,500 officers and men, was ordered to erect a gun battery on the high bluffs below George Washington’s Mount Vernon home at the White House on the Belvoir peninsula. The White House was a fishing office located on the Virginia shoreline of the Potomac, on property owned by the Fairfax family. In 1737, Colonel William Fairfax had chosen to build his plantation manor on the bluffs and named it Belvoir, literally “beautiful to see.” The Fairfax manor house had been severely damaged in a fire in 1783, and had not been occupied since.

Born on February 1, 1780, the 34-year-old Porter had already had a distinguished naval career. He twice had escaped impressment by the British while serving on merchantmen in the West Indies in the 1790s. Porter was on board the USS Constellation in 1799 when she captured the French frigate Insurgente during the undeclared naval war with France. During the Barbary War with Tripoli, he was twice wounded while gallantly leading landing parties from Enterprise. As captain of the USS Essex when war was declared against Great Britain in 1812, he captured several merchantmen and seriously crippled British whale shipping in the Pacific. Although he was finally captured by a superior British force in Valparaiso Harbor, Chile, Porter was paroled and returned home in time to participate in the Potomac operations. (He also fathered David Dixon Porter and adopted David Glasgow Farragut, both destined to be distinguished Union Civil War naval officers.)

Militia on the Belvoir Bluffs

Porter believed the American forces could use the Belvoir position to shell the enemy squadron when it attempted to pass. The bluffs, 30 to 60 feet high, were so high that it was thought the British would be unable to elevate their guns sufficiently to return fire. The British would also be largely restricted to the shipping channel, close to the Virginia shoreline. A second fort, commanded by Captain Oliver Hazard Perry, hero of the Battle of Lake Erie, was to be constructed five miles below the White House at Indian Head on the Maryland side of the river.

Pursuant to his orders, Porter proceeded down the west bank of the Potomac to the White House with a detachment of seamen and 50 Marine light artillerymen under Captain Alfred Grayson. He was accompanied by Captain John Creighton and several other Navy and Army officers, as well as Ferdinand Fairfax, owner of the Belvoir property, and a number of other civilian volunteers from Alexandria. Porter was met on his arrival by Hungerford, Brig. Gen. Robert Young of the District of Columbia militia, and two companies of Virginia militia riflemen from Jefferson and Richmond Counties. All eagerly awaited the arrival of their assigned artillery, consisting of three long 18-pounder and two 12-pounder guns. The Virginia militia had already started to clear away the trees along the bluffs for emplacement of the guns and to prepare positions to protect the rear of the battery.

At the moment of their arrival, the British brig HMS Fairy with 18 guns was seen coming upriver. Dispatches warning of Fairy’s approach arrived from the task force commander at Benedict, Maryland. The Virginia militiamen immediately took their positions and employed two small 4-pounder guns to open a brisk fire on the British. The American guns sent shot and canister smashing into the unsuspecting ship while hidden riflemen poured a murderous volley into the decks, which were crowded with British seamen unguardedly doing their laundry.

Fairy was able to pass by under a fine breeze after firing one broadside as she crossed the American fields of fire. The militia riflemen continued following the ship along the bank and “greatly annoyed him by their well directed fire.” Only one American was wounded in the exchange. Porter later conceded to the Navy secretary that the bombardment served no other purpose “than to accustom the militia to the danger.” He also noted that the height of the American positions resulted in most of the British shot striking the bluffs harmlessly, well below their breastworks. Baker informed Gordon that he had seen Americans cutting down trees and building additional batteries and warned that they intended to contest the British squadron’s downriver passage.

The British Withdraw from Alexandria

When Gordon learned of the attack on Fairy, he promptly began his withdrawal from Alexandria. Within a few hours, he had gathered all the captured merchant ships under the protection of his frigates and bomb ships and set sail down the Potomac. Alexandria’s trials had ended when the last of the eight British warships left the port on September 2. The city had been spared destruction. Yet residents remained apprehensive, fearful that any harassment of the enemy on its withdrawal down the Potomac might provoke the British to return and pillage their city. Wary officials did not hoist the American flag. When Rodgers entered Alexandria that Saturday, in preparation for implementing the use of his fireships, he was indignant at not seeing the Stars and Stripes flying over the city. The flag was quickly hoisted, but this did not stop many of Rodgers’s officers, and the hard-pressed residents of Washington and Georgetown, from branding the citizens of Alexandria as cowards.

That night the rest of the American artillery arrived, and Porter erected a large flag, emblazoned with the patriotic slogan: “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights.” The following morning, September 3, with Cochrane’s order to withdraw uppermost in his mind, Gordon sent the British bomb vessel Aetna and the rocket ship Erebus downriver from Alexandria to spray the battery with a fire of shot, shell, and Congreve rockets, a bombardment that continued throughout the night. Porter also expected additional 32-pounder cannons to arrive from Washington, but when these guns arrived without carriages, he could mount them expediently only on barges. Until then, Porter made do with his five long guns and the eight smaller 4-pounder and 6-pounder pieces of Captain George Griffith’s Alexandria artillery. He also built a furnace for heating solid shot.

Gordon’s Escape

Gordon was hampered by foul winds and constant groundings. When Devastation hung up on a shoal near Fort Warburton shortly after leaving Alexandria, Gordon had to anchor his squadron and prize vessels a few miles downriver at Mount Vernon to give the bomb ships some protection. Whereupon Rodgers floated three fireships downstream toward the British. Unfortunately for the Americans, the wind failed at a critical point, and Fairy towed away the fireships and chased the five accompanying barges back up the Potomac.

Throughout September 3, 4, and 5, the British continued to pound the American positions. Both sides traded hundreds of cannonballs with remarkably little effect. The first night, the British sent a cannonball through the house in which General Hungerford’s headquarters was located, and the next day the general moved his camp a quarter mile back from the bluffs. A militia officer on the scene noted that “General Hungerford did not lack courage, but he was not a military man and was out of his element when near cannonballs and bombshells.” The action log aboard Erebus recorded an unusual, if unexplained, moment: “Found one cask of rum shot through … lost 50 gallons.”

Finally, on September 5, Devastation was freed and joined the rest of the squadron. With a favorable wind, Gordon decided to make a run for it. Around noon, he shifted the ballast of his frigates to port, raising their starboard sides and elevating their gunfire. Sea Horse and Euryalus led the way, with the 21 prize ships and smaller vessels trailing. Porter had assumed that the larger British ships would be forced to come within 200 yards of shore—well within range of his own guns. Instead, the frigates anchored in line abreast to the Maryland shore, and their guns began pounding the top of the bluffs with redoubled effect. Within 45 minutes, every cannon on the bluffs was silenced.

Emboldened, the British bomb vessels discharged their mortars, loaded with musket balls, into the battery and the neighboring woods. Porter’s men hung on for as long as possible, but it was a hopeless mismatch, 13 effective American guns against the combined naval broadsides of 63 well-handled British pieces. The Virginia militia riflemen, under the command of Captain George W. Humphreys, did inflict some damage on the British ships from the water’s edge, and Captain Napier took a ball in his neck. Unable to stop the enemy, and seeing his own men starting to fall, Porter withdrew after 11/2 hours, and Gordon sailed triumphantly past at around 3 pm. Once the smaller vessels had passed, Gordon’s frigates cut their cables and followed the rest downriver.

Gordon’s escape past the White House was short-lived, and his squadron encountered opposition downriver along the Maryland shore at Indian Head. However, Captain Oliver Hazard Perry commanded only one 18-pounder, which arrived just 30 minutes before the combat began, and the gun soon ran out of ammunition, as did several 6-pounders under Lieutenant George Read. Perry’s force consisted of about 500 seamen and marines as well as local District of Columbia militia who were still smarting from the Bladensburg defeat. It was not enough. A quick consultation with his officers convinced Perry to retire to the rear, at the cost of one wounded soldier. Perry had maintained his fire for only an hour.

Erebus having grounded near Indian Head, Gordon could not withdraw fully until first light on the 6th. The British, unaware that the Americans had run out of powder the night before, were surprised that there was no further enemy resistance. With Sea Horse leading and Euryalus bringing up the rear, the squadron arrived back in the Chesapeake Bay on Friday, September 9, after Euryalus had grounded again for two days along the way. The expedition had lasted a total of 23 days, and during the 200-mile round-trip foray up the Potomac the British had suffered 42 casualties—seven killed and 35 wounded. Five seamen had deserted in Alexandria. It was difficult for Porter to determine his casualties, but he estimated them at 30 killed and wounded. Whatever the toll, he “esteemed the Americans fortunate,” considering the constant heavy British fire.

Gordon’s raid and the Battle of the White House might have seemed secondary when compared to the more newsworthy and sensational British assaults on Baltimore and Washington. Yet it had also been an achievement of sorts. Contrary winds, variable tidal currents, and the determined stand of Porter’s pickup force of seamen, marines, and militia had presented a number of challenges for the British captain. He overcame them all and brought his men safely back into the Chesapeake Bay. But there was also credit to be shared on the American side, which had stopped Gordon’s heavily armed squadron for four momentous days. Only the enemy’s superior firepower had allowed them to escape. Porter’s men could justifiably be proud of their conduct as well. It was a suitably mixed outcome for a war that, in its broader outlines, was equally confusing and unresolved.

Originally Published December 2009

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments