By Eric Niderost

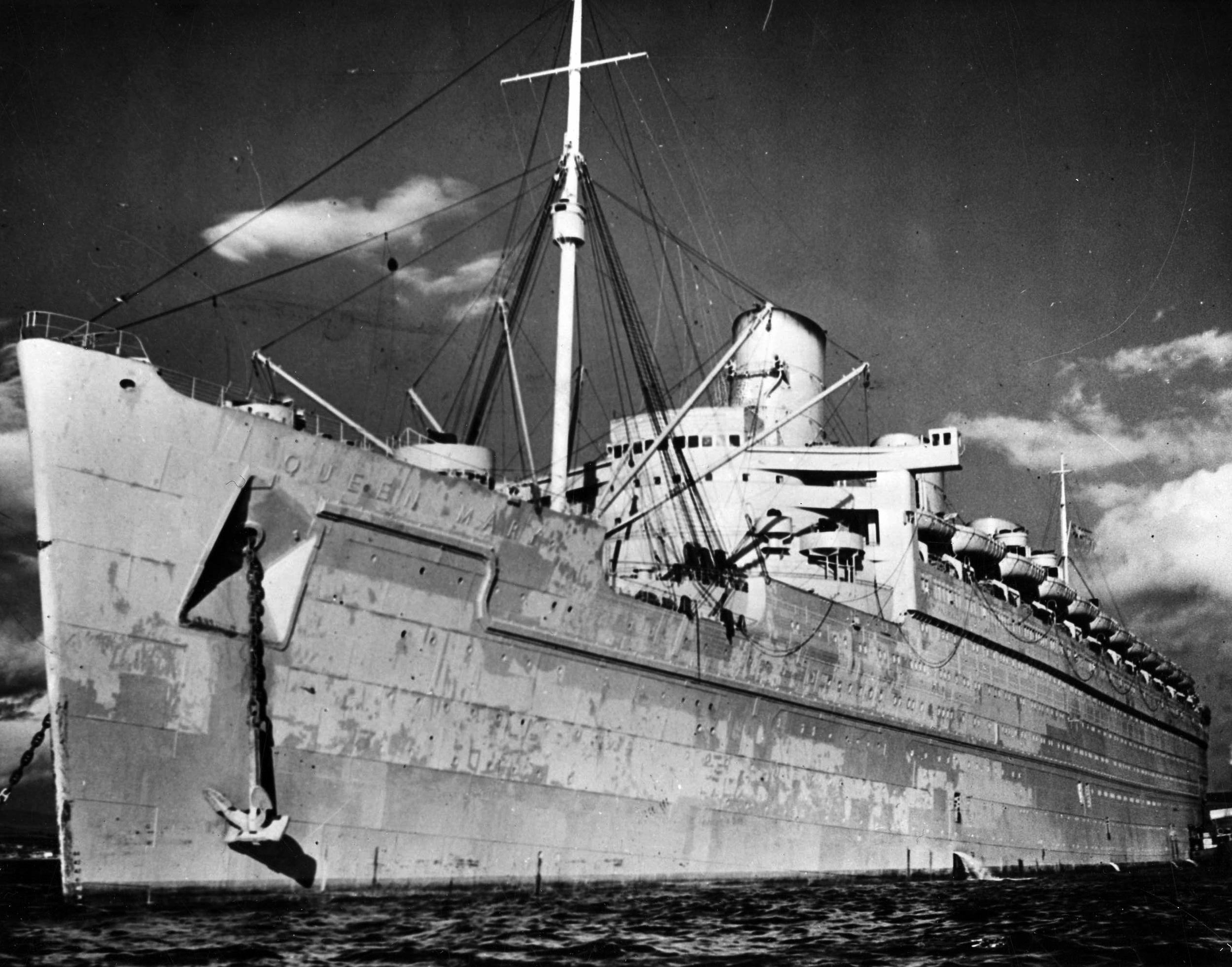

The late summer of 1939 saw Great Britain teetering on the brink of war with Hitler’s Germany. The years of appeasement and vacillation, of meekly acquiescing to Hitler’s insatiable territorial demands, were over at last. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government pledged to come to Poland’s aid if it was attacked. It was clear that if the Polish crisis could not be settled amicably Europe would be at war within a matter of days. Southampton became a magnet for thousands of people seeking to escape the Continent before hostilities began. Many were Americans, who cut their holidays short for fear of being trapped on the wrong side of the Atlantic. One such “refugee” was entertainer Bob Hope and his wife, Dolores, who booked passage on the RMS Queen Mary. The Hopes were not alone, and in fact Queen Mary had a record 2,332 passengers aboard when she left Southampton on August 30, 1939.

The Queen Mary had survived the Great Depression, an economic hurricane that had once threatened her very existence. The great liner was designed to resist the fury of nature, but could the Queen Mary also weather the storms of war? Only time would tell.

Why the RMS Queen Mary Was an Instant Legend

RMS Queen Mary was Britain’s entry in the fierce transatlantic passenger trade. Commercial aviation was in its infancy in the 1920s and 1930s, leaving passenger liners the only viable way to get to Europe. Before World War I, most shipping companies made their money in steerage, transporting thousands of poor immigrants to new and hopefully better lives in America. But when Congress curtailed immigration in the early 1920s, steamship companies like Cunard faced serious financial difficulties.

The solution was to build one or two huge liners that would gradually replace older, smaller steamships on the transatlantic routes. It would be much more cost-effective. The spartan accommodations of steerage would be upgraded to a much more comfortable “third class” in order to attract middle-income passengers. The ships themselves would be the main attraction of the journey, or, as the old saying put it, “Getting there is half the fun.”

Cunard would build the first of its great new ships in the Clydeside region of Scotland. Clydeside is a stretch of the Clyde River that reaches west of Glasgow toward Gourock and the Western Approaches. John Brown and Co., Ltd., a shipbuilder of great experience and skill, was selected for the task, but the work was hardly put in hand before the Great Depression deepened and severely weakened the British economy. On December 11, 1931, all work was suspended indefinitely and 3,500 workers were laid off.

The British government stepped in, offering subsidies if Cunard merged with its great shipping rival, White Star. All parties agreed, and work resumed in April 1934, after a hiatus of a little over two years. Shipyard hull no. 534 became the Queen Mary, hailed as the largest and “stateliest” liner ever built. The ship was named after the wife of Britain’s reigning monarch, King George V. The royal couple was on hand when the ship was launched RMS Queen Mary was an instant success, a legend in its own time. Passengers were awed by its great size, measuring 1,019 feet long and displacing 80,677 tons. In peacetime, it was designed to carry 2,119 passengers and 1,035 crew. Queen Mary may have been large, but it was also incredibly fast. The ship could average around 29 knots, even faster if pushed a little.

The great steamship was the physical embodiment of Britain, an amalgam of British taste and 1930s refinement. The Art Deco style may have had its origins in France, but on Queen Mary it epitomized the British liner’s elegance and sophistication. Mahogany and other exotic woods, many from Britain’s own colonies, were used in the interior. In a very real sense Queen Mary was an expression of the island nation’s far-flung empire. The ship went into service in 1936, and in August of that year it captured the fabled “Blue Ribband” prize for the fastest transatlantic passage. Queen Mary had traveled from Southampton to New York in a record three days, 23 hours, and 57 minutes, averaging over 30 knots.

Queen Mary’s growing fame attracted many celebrities of the period. Hollywood stars like Cary Grant could be seen in the Cabin (First) Class Dining Saloon, which featured a large intricately carved wooden map of the Atlantic Ocean, Europe, and America. Diners could follow the ship’s daily progress by observing a small crystal ship that was frequently repositioned on the map.

One Last Peacetime Voyage

The ship’s last peacetime voyage in August 1939 was anything but routine. Queen Mary’s captain was ordered to sail about 100 miles south of her normal route as a precaution against lurking German submarines. On September 1, the German Army invaded Poland, and shortly before midnight on September 2, just a few hours after Britain’s ultimatum was delivered to Germany, Queen Mary received an urgent dispatch from the Admiralty. The ship was ordered to “take all necessary precautions” to guard against submarine attack.

The crew worked with a will, painting over portholes and rigging blackout curtains on doorways. Extra lookouts kept eyes peeled for periscopes or the telltale white streak of a torpedo wake. Tension grew, and the fear among passengers was palpable. The liner Athena had been torpedoed a short time earlier, which did nothing to lighten the mood. In an effort to calm nerves, the captain asked Bob Hope to do a show for his fellow travelers.

The comedian rose to the occasion, and soon had passengers roaring with laughter. Noting the crowded conditions, Hope did a parody of his signature tune, “Thanks for the Memory.” While his audience laughed, Hope sang, “Thanks for the memory, Some folks slept on the floor, Some in the corridor, But I was more exclusive, My room had “Gents” above the door.…”

Queen Mary arrived safely at Cunard’s Pier 90 in New York City on September 5, and was ordered to stay put for the foreseeable future. Most of the crew went back to Britain to serve in the war, leaving only a small maintenance crew aboard. The liner was well guarded against sabotage, even though the United States was neutral at the time. There was a fear—real or imagined—that German spies might try to damage the mighty vessel.

Converted For Wartime Use

In March 1940, the Queen Elizabeth joined her sister ship, Queen Mary, in New York. The newer ship was unfinished and less vulnerable in the United States. Both vessels would perform a vital service in carrying thousands of troops to far-flung battlefronts around the world.

The Queen Mary stayed in New York for the next seven months, idle and seemingly forgotten. But this neglect was more apparent than real. Back home in Britain a debate raged in the highest circles of government over what to do with the two Queens. Some suggested that they were “white elephants,” and one member of Parliament seriously suggested they be sold. Besides being vulnerable to attack—or so it seemed at the time—the Queen Mary and her sister ship would eat up tons of fuel oil that might be better used in warships.

Saner heads prevailed, and on March 1, 1940, Queen Mary was officially called up for the duration. As a first step, her prewar livery of white, black, and Cunard red was replaced by a drab coat of what the Royal Navy called “Light Sea Gray.” This camouflage, together with her great speed, would be Queen Mary’s principal defense against marauding German U-boats.

Queen Mary left New York on March 21, 1940, bound for Australia via the Cape of Good Hope. Once down under, the ship would undergo a major refit to turn her into a troopship. The liner reached Sydney on April 17, a voyage of some 14,000 miles made at an average speed of 27.2 knots. Once in Australia, Queen Mary was taken to the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co. pier to undergo its transformation. When the workmen were finished, Queen Mary could take 5,500 passengers.

The RMS Queen Mary‘s Maiden Voyage as a Troopship

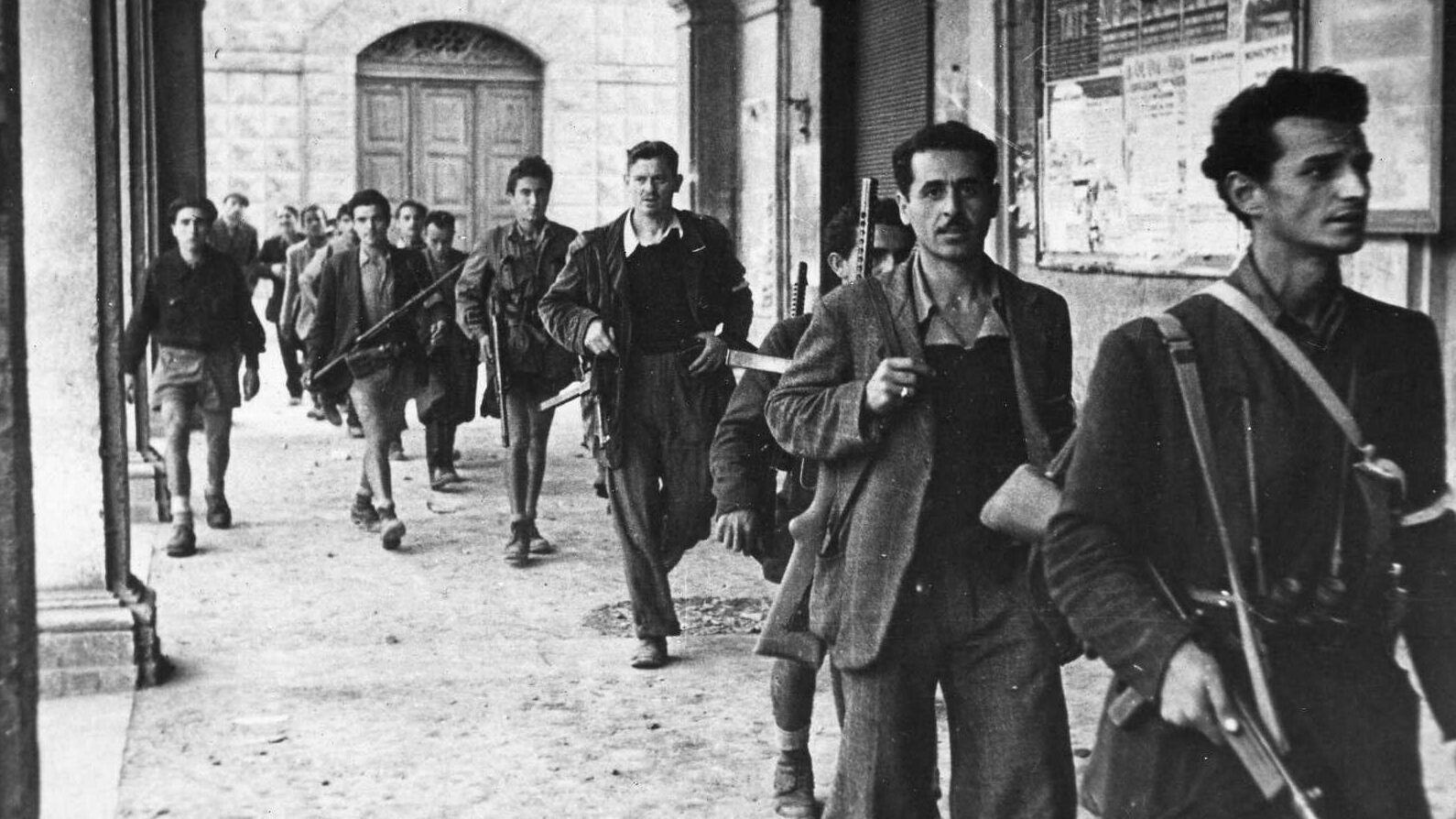

On May 4, 1940, Queen Mary left Sydney with 5,000 Aussie troops aboard. The great liner joined other “drafted” passenger ships similarly loaded with equipment and men, forming a huge convoy protected by the Royal Australian Navy. This first maiden troopship voyage was completed successfully, but the Queen’s arrival back in Britain coincided with the war’s darkest days. That spring, Hitler unleashed the blitzkrieg on Western Europe, overrunning Holland, Belgium, and ultimately France in a matter of weeks.

The British Expeditionary Force was pushed to the coast and barely escaped annihilation in the celebrated “Miracle of Dunkirk.” The British Army had escaped destruction but was forced to leave all its vehicles and heavy weapons behind. The island nation, now truly alone, braced itself for a possible invasion. There was only one bright spot in this litany of gloom: Winston Churchill had replaced the inept Neville Chamberlain as prime minister. Churchill was a man who truly appreciated the importance of Queen Mary and her sister ship.

Defending Against Sea Mines

Queen Mary’s primary mission would be to ferry troops to battlefronts where they were most needed, but she needed additional modifications. The ship was dispatched to Singapore, Britain’s great eastern bastion, where the transformations could take place. Japan, already embroiled in a major land war in China, soon occupied French Indochina. Tokyo’s ambitions knew no bounds, and its clear goal was nothing less than the control of East Asia.

The Japanese were careful to maintain peaceful relations with Britain and the United States, but war with the western powers was clearly on the horizon. In the meantime, the Queen Mary’s focus was the worsening crisis in the Middle East. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini hoped to carve out a new Roman Empire in the Middle East by invading British-held Egypt, which was the site of the Suez Canal, Britain’s lifeline to India and the Far East, a jugular vein of communications that had to be held at all costs. Mussolini’s badly led forces were easily routed, but Hitler upped the ante by sending the German Afrika Korps to aid his ally.

Queen Mary arrived in Singapore on August 5, 1940, and slipped into a huge Admiralty drydock for the scheduled modifications. A degaussing coil was wrapped lengthwise around the liner’s exposed hull as protection against German magnetic mines. The coil consisted of five miles of copper wire that, when charged with electric current, effectively neutralized the ship’s magnetic field.

The Route From Sydney to Bombay

After the extensive refit, Sydney became Queen Mary’s main base throughout 1941. In this period the liner shuttled troops from Australia to the Middle East, although she did not make the complete journey to the battlefronts. The ship usually stopped at Bombay, where the troops would transfer to smaller vessels that took them to Egypt.

The open ocean is one thing, but the relatively narrow confines of the Red Sea exposed the ship to too much risk. If the liner was sunk, the psychological blow to morale—not to mention the loss of life—would have been devastating. On a strategic level, Britain would lose almost 20 percent of its troop-carrying capacity during the war. It was the kind of percentage that might tip the scales in Germany’s favor.

Australian troops were tough and hearty, with a sense of humor that delighted in poking fun at the pretensions of themselves and others. They needed this irreverent wit because tedious weeks aboard the Queen Mary could try the patience of a saint. The war with Japan was still months into the future, and the chance of encountering a “rogue” German U-boat was remote indeed. Unfortunately, the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were designed for the cold North Atlantic, not the blistering heat of the tropics.

Torrid temperatures, not German torpedoes, became the chief threat in the summer months of 1941. Extra fans were jerry-rigged all around the ship, and saltwater showers were installed above decks. Awnings also were spread in an effort to deflect the sun’s burning rays. Unfortunately, these stopgap measures could not prevent temperatures rising well past the 100-degree range. Cases of heatstroke and heat exhaustion were multiplied, and on occasion there were one or two deaths from the oven-like temperatures.

The Queen Mary Under American Control

The December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor widened the war and brought the United States into the conflict on the Allied side. Churchill hurried across the Atlantic to confer with his new partners, although in truth the British and Americans had been cooperating with each other long before the formal declarations of war.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisers cordially welcomed Churchill that grim December, then set to work devising a strategy to deal with a two-front, two-ocean war. The Anglo-Americans agreed on a Germany-first policy, but where would the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth fit into the new realities of war? Their services as troopships were more needed than ever, but obviously the United States far outstripped Great Britain in terms of resources and manpower.

It was agreed that the Queens would be turned over to the Americans in a kind of reverse Lend-Lease, but that British Cunard crews would continue to run the ships under American operational control. But now that America was in the war, its troops were urgently needed, especially in the Far East. The Japanese were sweeping through Asia almost unchecked, and Australia was almost defenseless against Japanese aggression.

U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall met with Churchill to discuss how many people the Queens could carry effectively. Marshall had the idea of shipping at least 10,000 men, perhaps even 15,000, aboard one vessel. The figure is significant because a single division could number 15,000 troops.

Queen Mary’s lifeboats could carry a maximum of about 3,000 souls. Add all available rafts and floats, and the number might boost to 8,000. The liner often was unescorted because her speed was considered her best defense. But if the Queen Mary was torpedoed, roughly half of her passengers might meet the same fate as those aboard the ill-fated Titanic—death by drowning or hypothermia.

Churchill was a complete romantic who loved pageantry, tradition, and the past. Churchill was also a hard-headed realist who did not shrink from difficult and even controversial decisions if the need arose. The prime minister’s reply to Marshall was unequivocal: “I can only tell you what WE would do. You must judge for yourselves the risks you will run. If it were the direct part of an actual operation, we should put all on board they could carry…. It is for you to decide.”

In the end, the Queen Mary would carry 15,000 passengers, but not right away. In January 1942, the ship was in Boston undergoing another refit that would boost her passenger load from 5,000 to 8,500. The ship needed to upgrade her defensive capabilities as well. Before 1942, she had been protected by a single 4-inch gun and a few scattered Vickers and Lewis machine guns.

Now, she was to have the armaments roughly equivalent to a light cruiser. The list included 40mm cannon in five double mounts sited fore and aft and 24 single-barrel cannon emplaced in steel tub mounts along the ship’s upper structure. Six 3-inch guns were also aboard, as well as two antiaircraft rocket launchers near the aft funnel.

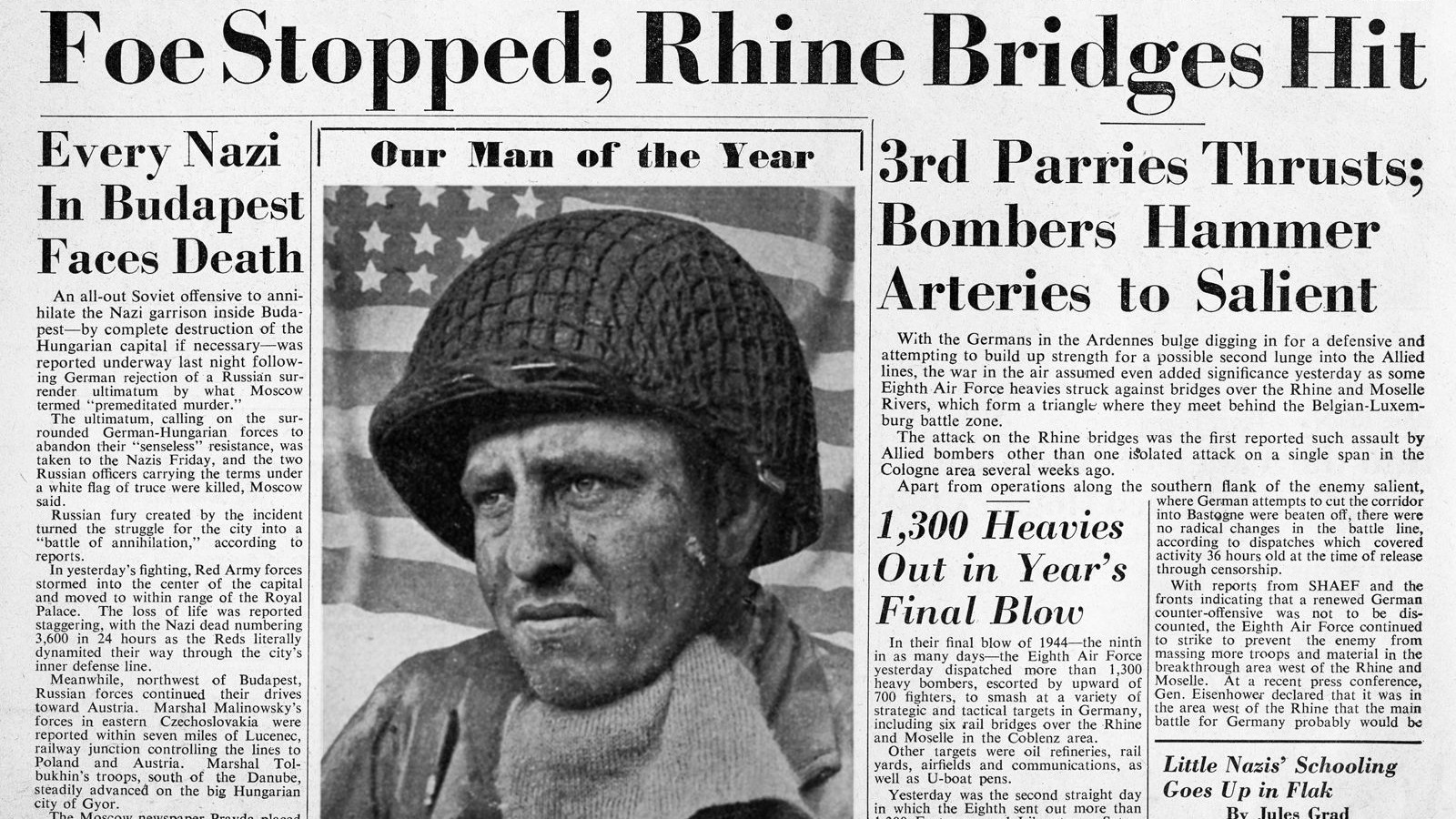

U-Boats on the Hunt

When the job was complete, the Queen Mary embarked 8,398 American soldiers, most of them artillerymen or ordnance troops of one kind of another. Her destination was Sydney via Trinidad, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, and Freemantle. The liner left Boston on February 18, 1942, under bright blue skies that seemed to augur a safe passage. In fact, this trip was one of the most dangerous of the Queen Mary’s entire wartime service. The period from January to August 1942 was fondly remembered by German submariners as “the happy time,” a period when they were winning the vital Battle of the Atlantic. In these eight months no less than 609 Allied ships went to the bottom, a staggering 3.1 million tons in all. The Queen Mary would have been the greatest prize of all. Adolf Hitler offered a million reichsmarks, about $250,000, and the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves to any submarine captain who could successfully torpedo the Queen Mary.

Increased U-boat activity around Trinidad forced a slight change in plans. The Queen Mary was diverted to Key West, and it was there that Captain James Bisset took command of the vessel. A 35-year veteran of the sea, he was nevertheless amazed by the Queen Mary’s great size. “Gazing up at her,” he later recalled, “I felt overawed at the responsibility soon to be mine….”

Once on the bridge, Bisset had little time for such reflections. The Queen Mary sailed on the westward side of Cuba, then east into the Caribbean, finally breaking into the wide Atlantic via the Anegada Passage. Bisset had no idea that two German submarines, U-161 and U-129, were not far behind following the same route.

The Queen Mary’s radio operator picked up a distress signal from a torpedoed tanker only 10 miles astern of the giant liner. In fact, this same tanker had passed the Queen Mary only 45 minutes earlier. Captain Bisset ordered full speed ahead, and the liner safely reached Rio on March 6, 1942.

The Queen Mary was in even greater danger in Rio. Count Edmondo di Robilant headed an Italian spy ring in South America, and according to some versions of the story had actually obtained a copy of the ship’s sailing schedule. Robilant or one of his confederates secretly radioed German submarines with the intelligence that the great ship was anchored at Rio, but luckily the message was intercepted by Allied intelligence.

Captain Bisset was told to refuel quickly and leave port as soon as possible. Forewarned, the ship left Rio several hours before its scheduled departure. The Queen Mary escaped in the nick of time. An oil tanker that left port about the time of the liner’s original sailing was torpedoed a few miles out to sea. It looked as if a German submarine had been lurking in ambush.

The Germans refused to believe that the Queen Mary had slipped the net; in fact they proudly announced the sinking of the great ship. Hearing this, Captain Bisset remarked to his communications officer, “Keep this news under your hat. Don’t let the troops know we’ve been sunk. It might worry them!”

The rest of the trip was uneventful, and the Queen Mary successfully reached Australia, where the Americans disembarked safely. The Yanks had behaved themselves but left distinctively American “calling cards”—wads of chewing gum stuck from stem to stern. Captain Bisset quickly revised the rules, adding chewing gum to the list of banned substances.

A GI Shuttle in the European Theater

By 1943, planning for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of occupied France, was well underway. Earlier refitted to accommodate 15,000 men, the Queen Mary made a significant contribution to the Allied build-up that preceded the invasion. In essence, the ship could carry an entire division across the ocean in less than six days.

Now permanently assigned to the European Theater, the giant vessel became a “GI shuttle” that ferried thousands upon thousands of American and Canadian troops across the Atlantic to Great Britain. It was decided that the Queen Mary could take 15,000 men only during the summer months, when the seas were calmer. The ship might weather choppy seas or a raging winter storm, but the packed men would be so tossed about that broken arms and other injuries could result. The idea was to deliver the men in one piece!

Gourock, Scotland, not far from where she was launched, was slated to be the Queen Mary’s home port for the duration. Southampton was the liner’s normal base in peacetime, but it was too near German-occupied France and subject to enemy air raids. Liverpool was another alternative, but it had also experienced German bombing. Gourock was beyond reach to all but a handful of German long-range aircraft types.

A Good Night’s Sleep on the Transatlantic Voyage

It was quickly realized that new rules and new procedures had to be adopted for the 15,000-man voyages, or all would dissolve into chaos. The ship was divided into three vertical sections—Red, White, and Blue—and every soldier coming aboard was given a colored button corresponding to the section where his unit was assigned. Visiting other sections was strictly forbidden. The Red section stretched from the bow of the ship aft to the number three stairway, excluding the sun deck. White covered everything between number three and number four stairways, and included the sun deck. Blue was from the number four stairway to the stern.

This overcrowding was feasible thanks in part to the standee bunks, which had replaced the ship’s earlier hammocks. Standee bunks were tiered sleeping spaces stacked up as high as six feet. There was only an 18-inch clearance between each standee, which did not help any soldiers who might be claustrophobic. Sleeping was done on a rotation basis, with each bunk shared by the men. In addition, at any given time one-third of the troops would sleep “topside” on the open deck.

The rotation system assured that each man slept inside two nights and then outside two nights. Sleeping topside was feasible only in the summer months because winters on the North Atlantic are too cold. Most GIs actually preferred outside, which was less dank and claustrophobic. Besides, the men reasoned rightly that those topside would have a better chance for survival if the ship was torpedoed.

Sergeant Jerry Cerrachio got some good advice during one of the Queen Mary’s outbound voyages to Britain. Since the upper standees were fairly high, it was only natural to select a lower bunk for convenience. “Don’t take that one, Sarge,” a friend cautioned. “If one of the guys above you throws up, it’ll wind up all over you!” Cerrachio immediately changed his mind and picked an upper bunk.

Rules and Regulations

Feeding such a multitude was no easy task. There were two main meals a day in six staggered sittings. Breakfast was available from 6:30 am to 11:00 am, and dinner from 3:00 pm to 7:30 pm. Soldiers could take as much as they wanted but were allotted only 45 minutes to complete their meals. As one group was exiting, another group would be queueing up to be served. Sandwiches were available for the men to take with them as they exited, to snack on between meals.

The former first-class dining saloon was the main enlisted men’s mess hall. It had been stripped of its prewar finery, but the great world map of earlier days was still in place, a reminder of happier times. Officers ate in the former tourist class lounge. Rank did have some privileges. Officers dined on regular tables and had food served by stewards. However, there was literally no “free lunch.” At the end of the crossing, it was expected that an officer would give the stewards a generous tip.

On such a crowded ship, rules and regulations assumed even greater importance. The Queen Mary officially was declared a “dry” ship—no alcoholic beverages allowed. Some rules were almost impossible to enforce. There was to be no swearing, no obscene or profane language, and above all no gambling of any kind. The GIs ignored the gambling ban, and probably drove the MP’s to distraction. Poker, blackjack, and crap games were a major form of amusement during the long six-day passage.

Some rules were rigidly enforced. There was a standing order that all personnel had to wear their life jackets and helmets when topside. Any person caught without these items had to forfeit his shoes. The story is told of an American admiral who must have thought his exalted rank put him above these things. He was caught without a life jacket and forced to surrender his shoes. He padded off in his stocking feet, thoroughly chastened.

Clandestine gambling apart, there was little to do on these long, cramped voyages. There was an occasional work detail, and some officers arranged exercise workouts. Movies were shown, but the Queen Mary’s film library was limited. At least the GIs were aboard for only six days. Cunard crew members had even less choice. It was said that one crewmember saw the Laurence Olivier film, Pride and Prejudice, 120 times!

Other soldiers passed the time by reading, writing letters, or simply talking to buddies. Those seeking religious solace could attend services in the Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish chapels. Mandatory lifeboat drills, ironic in that there were not enough lifeboats to accommodate all, also provided some breaks in the monotony.

The Stench of Seasickness

Life may have been tolerable, but it was anything but a pleasure cruise. The RMS Queen Mary was a legendary ship in any guise, even a troopship, but even before the war it had a tendency to roll in heavy seas. This was an unfortunate trait in the North Atlantic, well known for centuries as one of the most treacherous, even capricious, oceans in the world.

Seasickness was common, and the men rarely washed. There was always a lurking fear that one would be caught in the shower when the ship was torpedoed. Rather be dirty and safe than be clean and sorry. The net result was an atmosphere of cigarette smoke, sweat, vomit, and diesel oil that cannot be imagined by merely looking at period photographs.

The Queen Mary‘s Wartime Successes

In spite of the problems and discomforts, the Queen Mary was succeeding in its mission. During August 2 through 7, 1942, the ship carried a complete division, the First Armored, across the Atlantic. On that voyage, 15,125 troops and 863 crewmen were aboard. The ship reached a milestone on the July 25-30, 1943, passage. On that voyage she transported 15,740 troops and 943 crewmen, for a grand total of 16,683. It was the largest number of people ever carried by a steamship.

The Queen Mary also transported Axis POWs during her years of active service. Early in the war, the ship transported Italian prisoners to Australia. After the tide turned in North Africa, thousands of Germans also found themselves involuntary passengers aboard the great liner. Winston Churchill was aboard the Queen Mary for three trips, and during one of these voyages the liner also carried 5,000 German POWS.

On the whole, the Axis prisoners caused little trouble, but occasionally there were some minor flareups. In June 1942, some German prisoners scrawled anti-British slogans on a bulkhead. They were confined to the brig for a few days on bread and water. When some British personnel tried to counter with “Rule Britannia” graffiti, they too were thrown in the brig to cool off for a few days. One did not mark the Queen Mary’s walls, and the captain was determined not to play favorites!

The Germans would claim to have sunk the Queen Mary from time to time, partly in an effort to locate it. The Germans hoped that the false reports would prompt the Queen Mary or the Admiralty to break radio silence. If they did so, then the Germans could get a fix on the vessel. The British never fell for such a transparent ruse, and throughout the war the Queen Mary led a charmed life.

The HMS Curacao Tragedy

One tragedy did mar the Queen’s otherwise sterling wartime career. It occurred off the coast of Ireland on October 2, 1942, at about 2 pm. Captain Cyril Illingsworth was the ship’s master on this voyage, and at the time he was in the chartroom in the back of the bridge. Navigating officer Stanley Wright remarked to the captain that he felt unhappy that the escorting vessel, HMS Curacao, was getting too close. Illingsworth dismissed Wright’s worries, saying the light cruiser was used to escort duties and she “will keep out of your way.”

At the moment, the Queen Mary was executing a zigzag pattern, standard procedure for protection against submarines. The HMS Curacao was a light cruiser of World War I vintage, 450 feet long and 4,200 tons, commanded by Captain John Boutwood, a regular Royal Navy officer.

Suddenly, the Curacao moved close to the Queen Mary—too close. Recognizing the danger, the Queen Mary’s senior first officer, Noel Robinson, ordered, “Hard a port!” The horrified officer knew they had only two minutes to rectify the course and heading and to ward off disaster.

It was not enough. The Queen Mary struck the Curacao a glancing blow at an acute angle about 11 feet from her stern, which spun the smaller vessel around 90 degrees and left her vulnerable for a second, more devastating collision. The Queen Mary sliced through the Curacao’s hull like a knife though butter, cutting the unfortunate cruiser in two amid the sounds of escaping steam and tearing metal. The Curacao’s stern momentarily half capsized, its propellers spinning in the empty air, before finally disappearing beneath the waves. The front half, consumed in flames, floated a moment or two longer before going under.

Within seconds, the sea was a thick, viscous mass of oil slicks and screaming, half-dazed survivors. The Queen Mary sailed on without stopping—those were the standing orders—leaving smaller ships to pick up survivors. Only 101 sailors out of a complement of 429 officers and men lived to tell the tale.

Damage control parties quickly examined the Queen Mary’s bow and found an 11-foot hole at the point of impact. There was serious flooding to the forepeak, but as long as the watertight bulkhead held, there would be no serious danger. Speed was reduced to less than half, about 13 knots. The ship was inspected and deemed seaworthy. There was no need to replace the damaged bow, at least at the time.

The tragedy had been caused by a series of wrong assumptions, small miscalculations, and bad timing thoroughly based on human error. Both captains were men of ability and sound judgment. Though he was not entirely responsible for the disaster, Captain Illingsworth automatically thought that the Queen Mary would have the right of way. It was a fatal assumption.

The RMS Queen Mary‘s Long Voyages of World War II

The RMS Queen Mary then embarked on one of the greatest troop delivery shuttles in her career. Dubbed the “long voyage,” the vessel went from Scotland, to Suez, and to Sydney, Australia, and then returned to Gourock. Total round trip mileage was 37,943 miles.

The Queen Mary and her sister ship, Queen Elizabeth, were a vital part of the war effort. Indeed, many claim they helped shorten the war by about a year. Without the massive buildup provided by the Queens, D-Day might have been postponed until 1945. Between June 1943 and April 1945, the Queen Mary carried nearly 340,000 American and Canadian troops on journeys that covered 180,000 miles. The political consequences were immense. If the Western allies had been delayed, Stalin’s Red Army might have spread Communism beyond the reaches of Eastern Europe.

It was Winston Churchill who summed up the matter best. “Built for the arts of peace and to link the Old World with the New,” he later wrote, “the Queens challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the Battle of the Atlantic. Without their aid, the day of final victory must unquestionably have been postponed.”

Eric Niderost is a college professor in Hayward, California.

Hi Eric… Thank you so much for your well researched information on the Queen Mary.

I have a shoe box of memorabilia and souvenirs collected by my uncle, Leslie Jack Connolly, throughout his life. I came across a postcard of the H.T Queen Mary and two menus from the officer mess, dated January 1941, and just had to find out why he had collected these items.

I knew he had been in the Australian Army and I also knew he had served in the Middle East and now I know how he got there. He left Sydney, Australian on the Queen Mary at the end of December 1940, or the beginning of January 1941 and arrived in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka on the 31 January, 1941. His brother Eric Sydney Connelly was also with him.

So thank you again for your information on the Queen Mary.

Regards

Vicki

I just came across a letter from my father, John Oliver Fletcher, to a family friend, detailing his war time experiences as a pilot in the RAF. As a side note at the end of the letter, he left this comment: “The stamp on your envelope is interesting. It shows the very first building that I ever saw in Canada after leaving the Queen Mary with a hole in it at Boston before heading for New Brunswick.” I have vague memories of my father describing the tragedy and the result… but did not have any real idea what a big deal it was, as he tended to brush things off, I think, as a way to make them easier for us to understand. Much of the emotional toll of war was not communicated, but he did refuse to ever go on any type of vacation cruise, saying that they were a waste of money. I now understand that there was much more behind that stance than he was able to communicate. Thank you for your detailed article enabling me to better understand who my father was long before I arrived.

Hi Vicki – We would love to hear more about your uncle’s connection with the RMS Queen Mary and maybe able to help provide more detail of his time onboard the ship. Please reach out if interested. [email protected] – Foundation for the RMS Queen Mary ( http://www.Qmi.care) Thank you

My dad was a sailor on the Queen Mary I around 1944-1945. He remembers ferrying American troops across the Atlantic. Interesting to hear about the history of the ship.

Hi Pauline – We would love to hear more about your Dads’s connection with the RMS Queen Mary and maybe able to help provide more detail of his time onboard the ship. Please reach out if interested. [email protected] – Foundation for the RMS Queen Mary ( http://www.Qmi.care) Thank you

1944, I was 4 on holiday at the Isle of White. I grew up with the memory that a man on horseback rode along the beach telling everyone to get out of the water as the Queen Mary was either coming or going out of Southampton. Could this be a true memory.

My dad, Joseph Kohout, was with the Battery B, 743rd Battalion, Coastal Artillery (AA), when his unit was one of several on the QM during its ’40 Days & 40 Nights’ voyage, 2/18/42-3/28-42. He ended up in New Guinea with Aussie units as an AA gunner. Said he remembered the Rio de Janeiro port call. Said the troops on the QM were issued surplus WWI kapok life jackets which were mostly no good when they had a pool filled with water to test them. Kapok tree floss inside had deteriorated! Lost its ‘buoyancy’; didn’t help morale much! Also said he was trained to shoot down German/Italian planes and thought he was being sent to Britain, not the South Pacific, and had to learn Japanese plane silhouettes and markings once he got there.