By Duane E. Shaffer

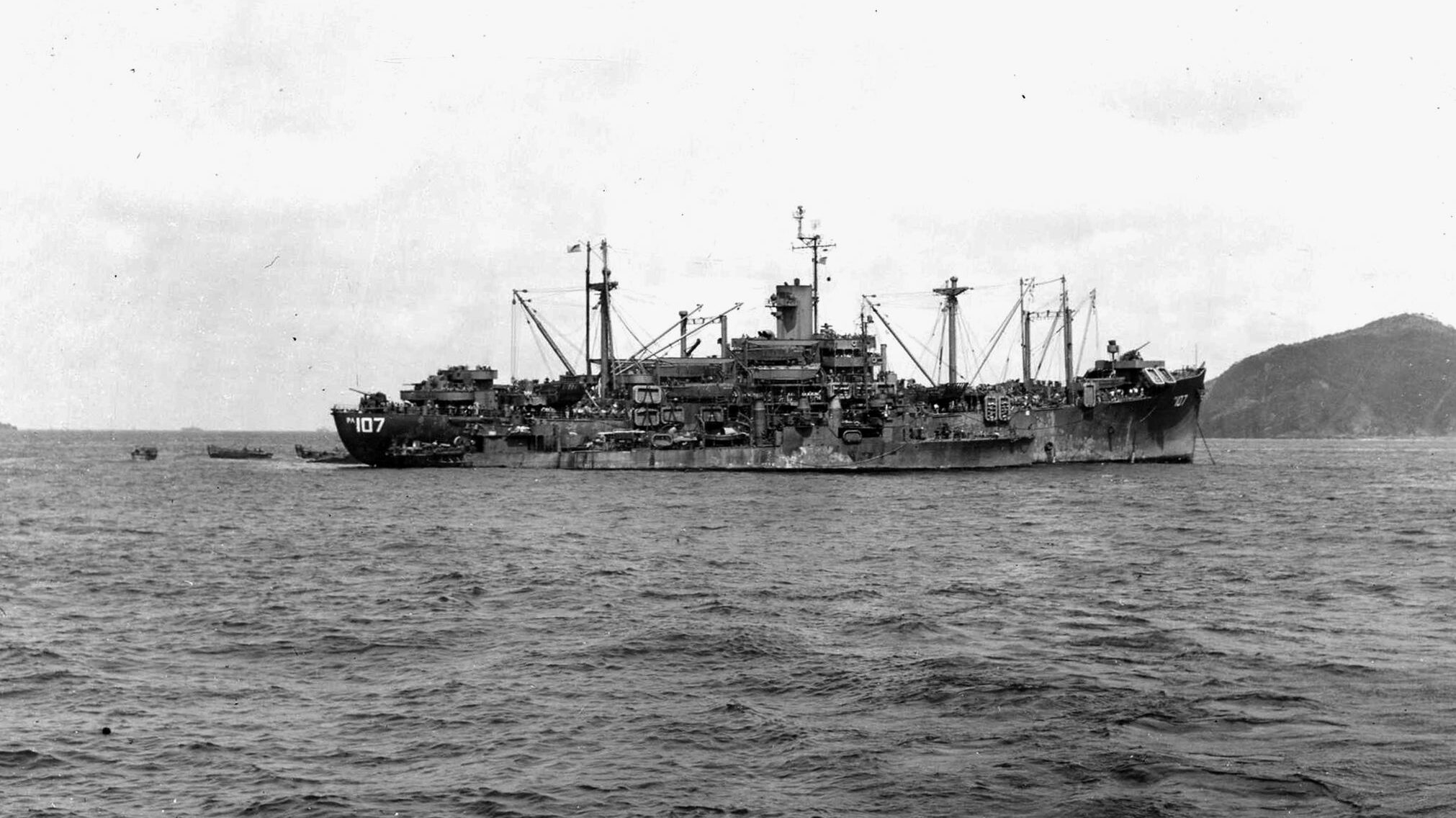

More than 60 years ago, in April 1945, the war in Europe was winding down to its inevitable conclusion. Prospects for victory in the Pacific were looking brighter, but the war was far from decided. The Americans had the Japanese on the ropes and the ever-shrinking Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was now limited to the Ryukyus and the home islands of Japan. However, for the American sailors aboard the Bayfield-class attack transport USS Goodhue, the war had yet to begin.

This is the story of one eventful day in the life of the Goodhue during the Pacific War. The officers and ratings of the ship were about to participate in the last great campaign of World War II, the capture of the strategically important island of Okinawa. This sanguinary campaign cost the United States 36 ships sunk, with the loss of nearly 10,000 sailors dead or wounded. The Army lost 4,675 dead and nearly 19,000 wounded. The Marine Corps, which bore the brunt of the fighting on the island, lost almost 19,000 dead and wounded. This was the price that America paid for taking a small piece of real estate that would serve as a springboard for an invasion of the Japanese home islands. If the Japanese resistance was this intense on and around Okinawa, what would it be like in the invasion of the Japanese mainland?

Opposing Operation Iceberg: Japan’s Kamikaze Waves

Planning for the campaign that would be known as Operation Iceberg began in the fall of 1944, about the same time as the commissioning of the USS Goodhue. The Joint Chiefs of Staff had evaluated all of the plans that had been discussed to bring about the final Japanese defeat. Which plan was better: bypass the Philippines, advance in China, or occupy Formosa? The Joint Chiefs adopted a strategy involving a landing in the Philippines as well as on the islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Following the costly victory on Iwo Jima, and while operations in the Philippines were ongoing, U.S. forces landed on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. Thoughts of hope for the future would be on the minds of the American servicemen in the Pacific that Sunday, but the only thing that was on the minds of the Japanese was to stop the American advance at any cost. Countless thousands of Japanese sailors and airmen would die in the attempt to halt the American juggernaut.

Japanese strategists discussed the best way to defend Okinawa. It was first argued that an aggressive attack against the Americans after they landed was the best strategy. Then, the idea was put forward that it might be better to let the Americans land and then grind them down in a battle of attrition. Then there was the darker alternative: that of the massed waves of suicide planes and boats known as the kamikaze. It was the latter two options in combination that American soldiers and sailors would confront at Okinawa.

The USS Goodhue

Scattered kamikaze attacks on American warships had occurred as early as 1943. Vice Admiral Takajiro Onishi had developed the concept of the kamikaze as a desperate suicidal effort to inflict serious damage on warships of the U.S. Navy, particularly its aircraft carriers. In doing so, it was hoped that the American tide would be slowed or even stopped. Although the kamikaze were not unknown to the Americans, the fury of the massed attacks thrown at the fleet off Okinawa was something that had not been previously experienced.

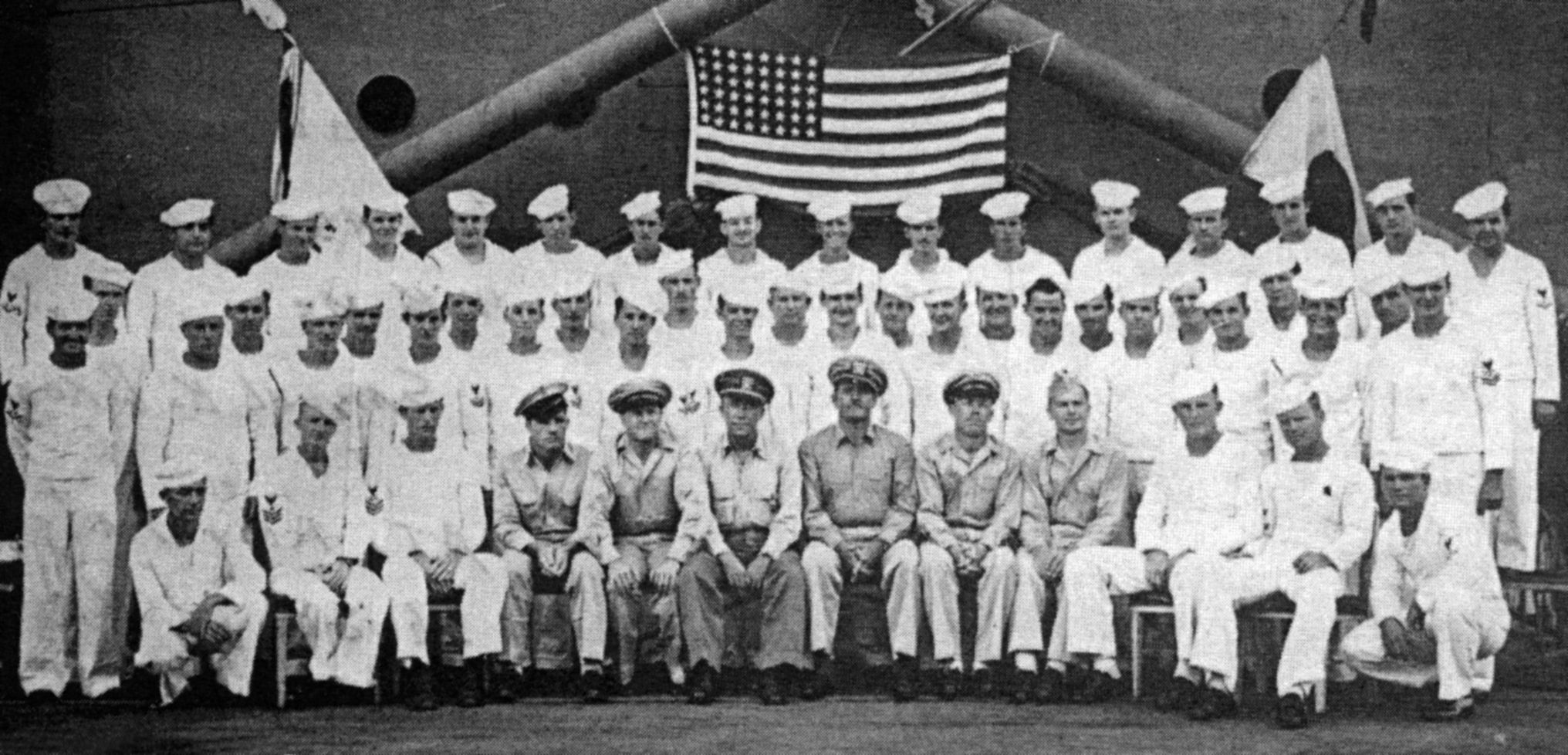

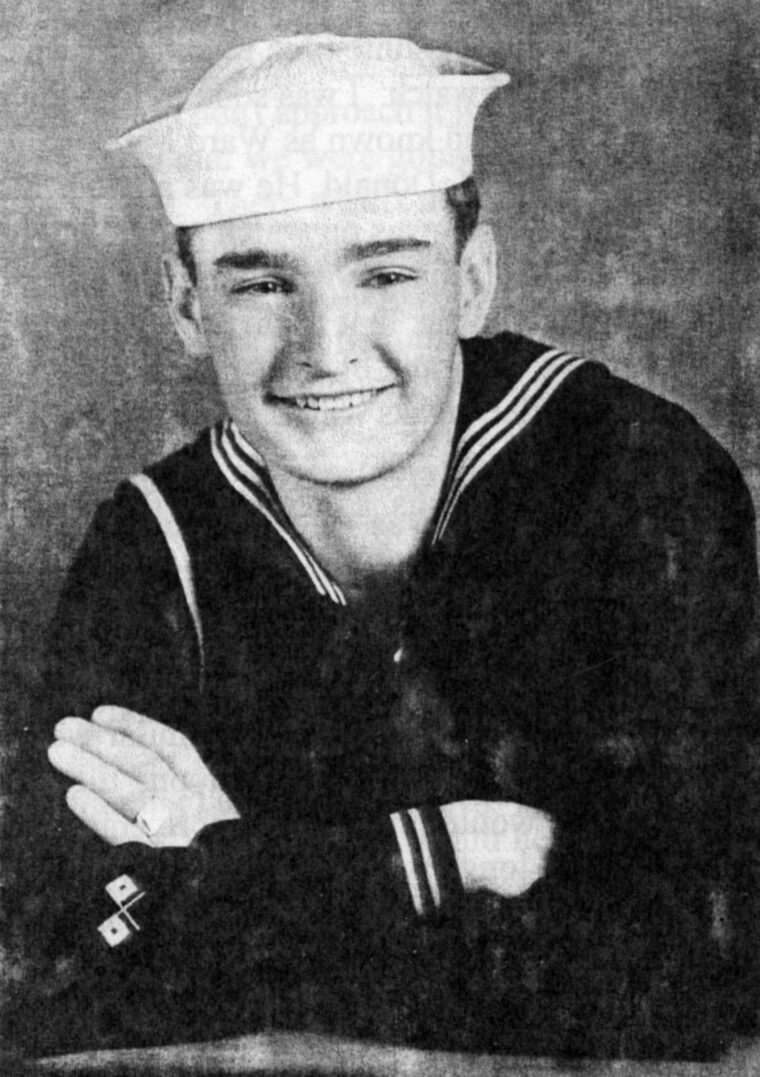

Ward McDonald, a 17-year-old signalman from Seattle, Washington, described the Goodhue’s shakedown cruise off San Pedro, California, in December 1944. “One early morning we got underway for our shakedown cruise … down the coast of California. A gunnery practice at a towed target proved our ability to have a shell from the ship’s 5-inch guns get within a quarter mile of the target. We swung compass, did a few maneuvers as well as swab the decks of vomit as the boys from Nebraska would leave go of their breakfasts. What a sight. I was wondering if they would even allow us to join other ships for a wartime effort. Somehow we made a successful shakedown.”

The Goodhue had two 5-inch dual-purpose gun mounts fore and aft, two single and two twin 40mm antiaircraft guns, and 18 20mm guns with which to protect the 51 officers and 524 enlisted men aboard. The ship was able to carry all the equipment necessary for an amphibious landing, including 1,200 troops and 15 landing craft. Powering everything was one General Electric geared drive turbine that could raise 8,500 horsepower.

“A day or so later during the loading of ammunition, food stuffs, fuel and the like, I noticed large boxes of foul weather gear coming aboard,” remembered McDonald of the days immediately following the shakedown cruise. “It appeared we were headed for a cold climate.” Days later, when the Goodhue was steaming southwest instead of north, McDonald observed, “The foul weather gear had been a ploy…. The military needed to make it appear obvious that we were heading north.”

The Goodhue had loaded her cargo in California and sailed away from the West Coast on January 4, 1945. She arrived at her first destination in the Admiralty Islands on January 21, where the ship picked up more cargo and passengers. Reaching Hollandia, New Guinea, on February 4, the Goodhue received her new commander, Captain J.L. Allen. Under Allen’s command, the ship took its place as the flagship of Transport Division 51. This meant that in any action they would be encountering, the Goodhue would be at the head of the column and most vulnerable to attack.

The Goodhue sailed to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines from February 4 to 12, carrying supplies to bases in the area. The officers and men underwent vigorous amphibious training exercises until February 25. By the end of the month, the Goodhue was loading troops and supplies for the coming campaign against Okinawa. There were more practice landings, and then it was time for the real thing. The ship got underway for Okinawa on March 21, but there would be one more stop along the way.

The small islands of Kerama Retto, just south of Okinawa, were to be secured to serve as a staging area for the invasion of Okinawa itself. A mighty American armada, which included the Goodhue, put troops ashore on March 26 to secure the island group. Compared with what was in store for them, the landings at Kerama Retto were a cakewalk.

Even so, McDonald voiced the opinion of many American servicemen in the area when he said, “March 26, 1945. Hell was upon us in every fashion. From the water we had the dreaded suicide boats, from the air the deadly kamikaze and on the beaches we had the fanatics. There was not to be a breather for anyone…. We encountered 82 air attacks in the next 30 days alone, most of them kamikaze. The reason for all this attention was we were getting very close to the main Japanese strongholds…. They would throw everything they had at us.”

As the kamikaze attacks against the American fleet intensified, the sailors aboard the Goodhue improved their defenses by bringing up on deck several of the Army’s field guns that they were transporting. “They just seemed to appear out of nowhere,” said McDonald of the suicide boats, “and if you weren’t alert they would get beneath your gunnery field and … the charge would blow a sizeable hole in the side of the vessel at the waterline.”

Airborne Attack on the Convoy

The Goodhue was anchored off Kuba Shima when the main landings against Okinawa went in on April 1. More than 1,300 vessels had assembled off the island, and the landing craft had been lowered and were circling in the water while the prelanding barrage softened up the beaches beginning at 5:30 am. Sixty-four American aircraft from the nearby carrier group also attacked the island before the landing craft hit the beach. By the end of the day, a 15,000-yard beachhead was secured and thousands of troops had landed.

At 4:15 pm on April 2, the Goodhue was underway from its anchorage at Kuba Shima to deliver the 307th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 77th Division to its destination on Okinawa. Cruising in a three-column formation of transports, the Goodhue led the right column with the transports Telfair, Mountrail, Drew, and Montrose falling in behind at 1,200-yard intervals. The distance between the columns was 600 yards. The Goodhue kept pace with the guide ship Chilton, which was leading the center column, and Henrico, which led the left column. As the vessels approached the combat zone, they began to zigzag to avoid enemy submarines.

At approximately 6:30 pm, a dozen kamikazes attacked the small armada of transports and supporting destroyers. The Goodhue’s log noted, “1837 [we] commenced firing with after starboard 20 millimeter guns and 40 millimeter guns on enemy aircraft attacking the convoy from abaft the starboard beam … 1840 … Henrico seen to be hit in midship section … 1842 … Telfair seen to be grazed by suicide plane.”

The Goodhue and her sister ship Telfair were attacked by three planes. The Telfair gunners combined with the firing from the Goodhue to destroy one of the attackers in midair. A second plane rammed into the starboard and port kingposts of the Telfair, then fell over the side of the ship. The third plane was headed straight for the Goodhue.

Hit by a Kamikaze

Radioman Second Class Jack Kenewell recalled the result of the third Japanese aircraft’s attack against the Goodhue: “After knocking one Betty [Mitsubishi G4M bomber] out of the air with a salvo from our 5-inch aft, a Jap suicide plane came in over our bow only seconds later. We didn’t have a chance. He hit our crow’s nest and did some damage … I was bleeding badly with a wound on my chest, neck and feet.”

The Goodhue’s log recorded, “1848 … one enemy plane observed paralleling our course to starboard at 3,000 yds. Plane was seen to change to an approach course at … 1,000 ft. The plane was taken under fire by the forward 5”/38 gun at a range of 1,500 yds.”

The aircraft attacking the Goodhue was a Kawasaki KI-45 Toryu, known as a “Nick” to the Allies. This was a twin-engine, long-range escort and reconnaissance fighter. It was most likely armed with two fragmentation bombs carried under the wings.

The combined fire from the Goodhue and the other transports hit the Nick in the port engine and cockpit area, setting it on fire. The Goodhue’s log reads, “1850 … suicide Japanese plane crashed into the mainmast at the cross trees level. One part continued and exploded over the fantail, the other containing cockpit and at least one bomb, swung over the port side and exploded at about deck level … most of the plane fell flaming into the water.”

McDonald vividly recalled the attack of the kamikazes: “As soon as I stepped out onto the main deck I looked right into the cockpit of a kamikaze approaching us on the starboard side … I watched wide-eyed as the Jap plowed into the starboard side of the USS Henrico … blowing a hell of a hole completely through the superstructure … I was looking at the crew [of a 5-inch gun] about 10 feet away when their eyes grew huge and an expression of fear struck them all…. From the corner of my eye, I caught sight of a huge ball of fire and mass descending upon me…. I instinctively turned to my left and was ducking.”

In the brief moments described by the ship’s log and the narratives of Kenewell and McDonald, 27 men were killed and 117 wounded. Although the impact of the kamikaze had struck and knocked down the Goodhue’s 30-ton cargo boom, the majority of the dead and wounded were hit when bomb fragments and shrapnel rained down on them as the plane disintegrated. The Telfair, Henrico, and Chilton had also sustained major damage. The destroyer Dickenson had taken a direct hit on its bridge, killing 53 sailors, including the captain. The ship was so seriously damaged that it later had to be scuttled.

The Henrico had also taken a direct hit from a suicide plane, later identified as a Frances (twin-engine bomber). This kamikaze had plowed into the superstructure, killing the captain, a colonel of the 77th Division, and scores of Navy and Army personnel.

“Hundreds of Kamikaze Planes.”

Stunned but not wounded, McDonald was taken below for a time. When he came to his senses, he went back out on the deck. “When I stepped out on the after deck, I found death and destruction everywhere I turned,” he recalled. “The first thing I noticed was the after 5-inch gun placement was out of kilter and there were no identifiable body parts of any of the gun crew. They were just gone … screams, moaning, orders being given and bodies everywhere…. As I peered over the top of a ladder onto the deck, I saw a finger with a gold ring still on it … just a mass of flesh everywhere.”

Radarman Third Class Samuel Keels Brockington was drafted into the Navy from Kingstree, South Carolina, in March 1944. He was assigned to the Goodhue that summer. “The man in the crow’s nest where the plane hit was just wrapped in metal,” he remembered, “and pieces of the plane were on the boat.”

Damage control parties extinguished several fires and then began the grim task of collecting the dead and wounded. Radarman Third Class Howard G. Hobbs was assigned to this detail, and the memories of the sights and sounds of that evening haunted him for his entire life. Motor Machinist Mate Third Class Francis “Red” Nagle was in charge of piloting one of the landing craft used to ferry troops and supplies to Okinawa. On the day the Goodhue was attacked, he recalled looking into the sky and seeing “hundreds of kamikaze planes.”

164 Ships Damaged by Kamikazes

The Goodhue’s loss had been severe. With 21 dead and more than a hundred sailors wounded, the transport had lost one-quarter of its crew. Twenty-four soldiers from the 307th Regiment also became casualties. At least five of the 15 attack transports that left Kerama Retto that evening sustained damage from kamikaze attacks. During the Okinawa campaign, 27 of the 36 U.S. ships sunk had been attacked by suicide planes. A total of 371 U.S. ships were damaged at Okinawa. Of that total, kamikaze attacks were estimated to have accounted for 164.

After the attack of April 2, the Goodhue withdrew with a destroyer escort back to the Kerama Retto anchorage for repairs. Along the way the dead were buried on the small island of Zamami Shima, and the wounded were loaded onto hospital ships for treatment.

“That night I worked on the injured doing everything I could,” said Brockington. “The next day they were sent to the hospital ships. I helped sew canvas bags for those who were dead. The evening before the attack on our ship, which was the evening of the invasion on Okinawa, I was talking to a guy from Tennessee. He said, ‘Brock, if we get home let’s do so and so.’ I told him that the invasion that morning had gone well and instead of saying ‘if we get home’ let’s say when we get home. He said that sounded like a good idea. I sewed his body bag the next day.”

Kenewell, who had received some serious wounds when the Japanese plane struck the ship, recalled the condition of the sailors on the hospital ship around him. “I saw some horribly mutilated men, some with shrapnel all over their bodies, others with burns. Undoubtedly these were the worst cases, some with no chance of recovery, dying by inches … some with their eyes burned right out of the sockets. They would never really recover.” After several days of rest at the anchorage, the troops aboard the Goodhue eventually splashed ashore on Okinawa.

The USS Goodhue‘s Battle Star

The USS Goodhue received one battle star for its participation in the Okinawa campaign. The ship was decommissioned on April 5, 1946, and sold to the U.S. Maritime Commission for commercial service in 1947. Renamed the Hawaiian Citizen, she plied the Pacific Ocean for another 34 years, 21 of those as a container ship. The Hawaiian Citizen was finally scrapped in Taiwan in 1982. The ship is gone, but many of her veterans are still around. They gather every year for a reunion and mourn the shipmates lost in the previous year.

The ordeal of the USS Goodhue is not unique among the U.S. Navy warships subjected to the ferocious kamikaze assaults off Okinawa. However, it is representative of the battle that took place there and of the carnage that could well have been expected if an invasion of the Japanese home islands had been necessary.

Duane E. Shaffer is a library director in New Durham, New Hampshire. His late father-in-law served aboard the USS Goodhue.

My father, Douglas R. Spencer served on the USS Goodhue as an officer. Reading this article has helped me to understand what happened during WWII. My father never talked about it. He died in 2013 and was 21 during the battle

My father, James Thomas Fitch, also served on the USS Goodhue. My father never talked about his service either. He died in 1988 and was 18 or 19 during the battle.

My father (Robert Lynch) was an officer on the USS Goodhue. He only reluctantly spoke about these events but enough to let us know the terror. Someone on the ship made a film of the various ports of call and the battle. This was circulated in the 1960s to the former crew members and probably now gathering dust in some attic.

I am pretty sure my great uncle, Ted Lannon, died during this attack on the Goodhue. We are trying to find out more information for our family history. If anyone knows any survivors that may have more information please contact me.

Hello Ted,

I was excited to see your comment about Ted Lannon. My sister and I are doing research on the Lannon family from the Raton / Trinidad / Pueblo area of CO and NM. The research is for a dear friend who very recently found she is the daughter of Ted’s brother, Milton. It would be interesting to talk with you and introduce you to a cousin you did not know you have.

My father was a naval gunner on the USS Goshen, a sister ship to USS Goodhue in the Battle of Okinawa. Growing up, he spoke “many times” with great pain about one night, breaking orders to “not fire” due to smoke screening, in order to fire on the approaching Kamikaze headed for the Goodhue. He said he “Gave it all he had” however the plane directly hit the Goodhue with several men dying. My dad was brought up for possible court Marshall the next day for breaking orders. The General said “release this man, I would have done the same.” Dad lived with that pain and guilt all his life, as being unable to blow the pilot out of the sky. Dad described that night with all men ordered below except for he and another gunner. The smoke cleared and he could see the Kamikaze above heading for its potential mass destruction. This article really brought life to this one of many terrifying events for my father and the details describing that attack.

My father served on the USS Goodhue as a Quartermaster Second Class and helmsman.

My great grandfather served on this USS Goodhue and another manually loaded guns as long as they could fire them. Mom told me stories he told them the terrible things he witnessed. They called him Pappy because he was older then most of the service men on the ship.

I just stumbled upon this article while looking up things on the 78th anniversary of the formal surrender of Japan. My father, Henry Clay Baugh Jr (Hank), from Philadelphia, served on the Goodhue. Like so many others, he didn’t talk about it much, and when he did, it was mostly the funny stories. I do remember him having a piece of a bomb that hit the ship that day. We didn’t know he had kept a diary on the Goodhue. We found it after my mother died, and when he had Alzheimer’s, so we couldn’t discuss it with him. Here’s the entry from that day (the longest entry in the diary). Some of the handwriting is hard to read. I’ve used (sic) to annotate where my take on the spelling may be wrong. The punctuation is his.

“We steamed out of Takoishima (sic) about 1200 (or 1700, hard to read) our Transp. Div and escort.

After chow Bonny, Banuski, Onion and myself were sitting down in quarters playing 500 Rummy, All of a sudden we heard 20m.m. fire and then G.Q. I grabbed my life bely and helmet and ran up on deck. My battle station was all the way aft. Repair 3. Fire party #6. As I ran by #5 hatch our 40mm got a Hamp which tried to dive in the PA 210. They had it in flames and in the water before any ships opened fire. An APD Task (sic) A plane (suicide) killing all but 6. Out 5″ AFT got one off our STB (sic) Beam. PA 45 Hendricks took 2 planes. One on each side of bridge. A Nick started his dive on us. #1 5” got his stb engine But he still kept on coming. The the 20s opened up. He tried to hit our Bridge but missed If he had been 10′ higher we would have been OK. His Right wing caught our After Mast and Crows Nest The Bomb went off in Mid Air

As soon as the firing started I began taking the fire hose off the rack. I had started up the ladder with it when the bomb went off. I was blown down the ladder and Julie landed on top of me. I asked him if he was ok. Then I went topside with the hose The 40mm clipping room was Ablaze. I handed the hose to Mungle (sic) and went below to get the kinks out. We had the fire out before repair 3 was topside. Then I rushed on deck to see what I could help at. I helped carry casualties to sick bay Ardron (sic) who didn’t have a G.Q. station was down there administering Morphine and Plasma. Julie and I each manned a 50, as there was still 2 planes after us. My gun jammed and I went over to feed for Julie. There was a lull in the fighting and I got down on my knees and prayed. I was scared but I had faith in my prayers. I know they were answered. Later some Army fellows came up and relieved us. We went below and helped with the wounded. It sure was bloody. We were up most all night.

Apr 3rd.

We Trans Ferred casualties this morning. 144 wounded 25 dead. We pulled into Tombstone Harbor. AKA Shima (Kerama) They took our dead over on the island to bury. It sure is hard hearing taps played in the afternoon.