By Kelly Bell

At 12:30 am, October 9, 1943, Commander Edward S. Hutchinson spotted his first targets as a submarine commander. His boat, USS Rasher, was on her maiden war cruise out of Brisbane, Australia, and every man in her was eager for his first taste of blood.

They were off Ambon when they sighted a pair of freighters that were zigzagging in antisubmarine patterns, deliberately making stalking difficult and protracted, but Hutchinson was tenacious. Throughout the night he trailed the careening targets, slowly bringing his boat within torpedo range. By the time he was able to commence his attack it was dawn. He fixed the targets in his periscope sights and fired a six-torpedo spread. Four missed, but the other two ripped open Kogane Maru. The 3,132-ton freighter went down swiftly while her sister ship blindly dumped depth charges that killed no one but hapless seamen who had jumped from Kogane Maru. With the surviving ship hurrying for shallow water and her crew doubtless radioing news of the attack and its location, Hutchinson, exultant over his first kill, turned his sub back to the open sea.

A Choppy Sector for the Rookie Crew

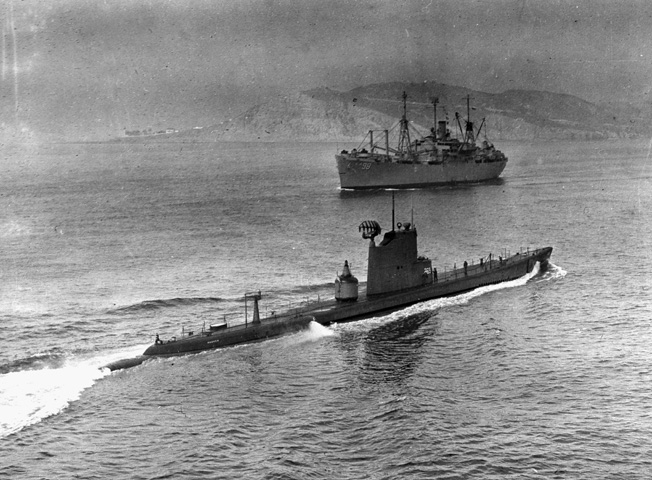

On December 20, 1942, workmen had broken the ice at the end of a ramp of greased fir tree trunks leading from the dry dock into the Manitowoc River outside Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The boat launched that sub-zero day was the U.S. Navy’s Gato-class submarine USS Rasher. Her hull number was 269, and she weighed 1,806 tons. Her construction had commenced the previous May 4, and she was the first of 28 submersible warships constructed by the Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company during World War II. There were six 21-inch torpedo tubes opening from the forward torpedo room, and the after torpedo room brandished four such tubes. During each of her combat patrols, Rasher would carry 20 torpedoes.

The 39-year-old Hutchinson, Rasher, and her first crew were delivered to the Navy on June 7, 1943. By the end of August, all training and loading were complete and the sub embarked for Brisbane for a brief refit and combat indoctrination. After these final preliminaries her next date was with the enemy.

New boats with rookie crews were usually sent to sedate sectors, but for state-of-the-art Rasher and her splendidly trained crew this rule was overlooked. Hutchinson and his command would steam into the Makassar-Celebes sector, which was thick with Japanese supply vessels and warships. By September 24, the last preparations were complete, and America’s future premier attack submarine sallied north from Brisbane to commence hunting.

Evading Two Destroyers

By October 13, Rasher’s patrol circuit brought her back to Ambon, and at 1 pm four Japanese ships chugged from the harbor while a sub-hunting floatplane circled above them. Two of the vessels were destroyers escorting for a pair of freighters, and when one of the six torpedoes Hutchinson fired at them proved defective and detonated seconds later, the destroyers were alerted to the sub’s presence long before her crew had expected.

Screaming for his diving officer to head for the depths, Hutchinson also ordered full speed to hasten the process. Passing the 90-foot mark, the Americans were thrilled by four reverberating reports as their torpedoes slammed into the 3,217-ton Kenkoku Maru, sinking her in 11,000 feet of water.

The destroyers commenced depth charging, but Rasher reached the thermal barrier where sharply differing temperatures in layers of water cause inaccurate sonar readings. Chief Pete Sasgen counted 24 hollow blasts fading away to the west as the frustrated sub hunters could not catch their quarry’s scent. Two hours later the Americans surfaced to find the area deserted.

Suspecting the destroyers and surviving transport had retreated into the harbor, Hutchinson stayed put for the next 24 hours. His prey never reappeared, and the following night he received an intelligence report directing him to the shipping lanes around the Talaud island chain 550 miles to the north. An enemy convoy was expected to pass through this vicinity about October 17, and the Allied command gave it high priority.

Taking Out a Tanker

Despite breakdowns in two of the boat’s four diesel engines, the submariners arrived at the Talauds on schedule but found only small sailboats and assorted fishing vessels. If the fifth-column operatives had been right about a convoy in the area, it had apparently taken a different route. The hunting turned very poor.

It was 2:30 on the afternoon of October 31 before Hutchinson’s lookouts spied a tanker’s masts poking over the horizon near the Celebes coast off Watcher Island. It was an old ship but so laden with crude oil that its decks were almost awash. Again a worrisome floatplane buzzed overhead, so the hunters trailed about seven miles behind their quarry for 51/2 hours until the plane had to depart to refuel.

The ship was evidently headed for the Japanese-held port of Manado, and before it rounded the Minahassa Peninsula, Hutchinson lined up his aft tubes and fired three torpedoes at 10:04 pm. Two minutes and 29 seconds later, two of the warheads impacted and blew the rusty oiler into a spectacular petroleum conflagration. The vessel turned out to be much smaller than the skipper had estimated. The late Koryo Maru had weighed just 589 tons but had been loaded with the most highly prized cargo afloat.

Spotted Twice

The hunters now headed north to just above the equator and the Balikpapan-Truk-Palau shipping lanes. On the afternoon of November 8, Hutchinson was in the conning tower making a standard periscope sweep when he noticed a column of smoke and a tall mast on the horizon. Barking orders to his men, he kept the target in sight as he maneuvered his boat into position for a stern attack. A spotter on the tanker’s deck trained his binoculars directly on the approaching periscope but somehow overlooked it. An escorting patrol boat was churning about 2,000 yards to the oiler’s port side, but Hutchinson gave it little thought as he aligned his ship and shot three torpedoes from 13,000 yards. Two of the fish hit and blew off the old tanker’s stern. It was the 2,046-ton Tango Maru. Unfortunately for the hunters, this victim had been empty and there was no roiling bonfire to punctuate her passage. The submariners would not have had time to watch anyway.

The patrol boat had been just 1,000 yards from the sub when the torpedoes exploded, and this time the periscope was seen. Bearing down on the raider at full speed, the ship began unloading depth charges before the Americans could reach the temperature gradient. Although some of the bombs went off close enough to rattle the sub, none were near enough to damage her. By 6:39, Hutchinson felt secure enough to surface. He found the seascape serenely empty.

Late that night the submariners sighted three more ships in the Makassar Strait and immediately set out after them, but, at 1am on the 9th, another vessel popped up on a course approaching the other three and converging on Rasher. Hutchinson had been sweeping around in a wide arc to attack the targets broadside, but to continue on this course would bring the newcomer alongside him. If he torpedoed the new arrival, his primary prey would be warned and escape. He elected to abort his end run and change course to approach the original targets in a risky, high-speed surface charge.

Turning around, Rasher advanced straight on the unsuspecting merchantmen in the bright moonlight while her men primed their last six torpedoes. As the attackers bore in, the victims inadvertently made the attack easier by swerving 45 degrees left, positioning themselves on either side of the submarine, and making for easy simultaneous bow and stern shots. At 1:22 am, the sub spat out four missiles from her fore tubes and two from the aft. Seconds later, the right-hand cargo vessel fired a signal flare to alert the escorting destroyer that something was afoot. Someone had seen either the torpedo wakes or the periscope, and the destroyer swung around to counterattack. A handful of randomly dropped depth charges went off far from Rasher. It was a fair swap—all six torpedoes missed. It was time for Hutchinson to head for port.

Willard R. Laughon Takes Command

Following his productive cruise on Rasher, Hutchinson was promoted to command of Submarine Squadron 22. Lt. Cmdr. Willard R. Laughon took Hutchinson’s place. Thirty-nine-year-old Laughon was fresh from antisubmarine patrol duties off Bermuda.

Following extensive drilling to help Laughon and his crew, many of whom were newcomers as well, mesh into a smoothly operating unit, Rasher weighed anchor on December 19 with orders to lay a minefield in the shipping lanes off Indochina’s Mekong Delta. Following this assignment, she was to commence a normal hunting patrol.

Late on the night of January 3, 1944, Laughon eased his boat into the shallows off the Indochinese coastal island of Poulo Condore and set out 11 magnetic mines. As the Americans moved back toward deep water, they received a message from the cryptographic section.

Counterintelligence had learned of a convoy heading north from Singapore. It was expected to pass through Rasher’s current patrol area around 6 pm on the 4th. Laughon was ordered to rendezvous with sister sub Bluefish and await the approaching tankers. The subs found each other with little difficulty, and Laughon and Bluefish skipper, Commander George Porter, laid plans to assail the convoy simultaneously from both sides.

The sea hunters located their quarry right where they had been told to expect it, and Laughon immediately bore in from the right and fired three torpedoes at the third ship in line. Seconds later, Rasher was rocked when one of the fish exploded prematurely just 400 yards into its run. Japanese sailors instantly opened up a wild barrage with deck guns. As Laughon whipped his boat around to bring his stern tubes to bear, he heard blasts behind him as Porter attacked another ship from the port side.

Another Kill for Rasher

In the gathering darkness it was difficult to draw a bead on the frantically maneuvering targets. Unable to get a firing angle for his aft tubes, Laughon turned toward his intended and charged. At this point, one of the oil-glutted ships exploded in horrific splendor. It was the one Bluefish had shot, and it seemed at least one of Rasher’s initial volleys had hit.

As Laughon positioned to finish off the cripple, the presumably undamaged, 10,000-ton Kiyo Maru suddenly cut in front of him. In his confusion, this vessel’s helmsman set his ship up for destruction. Rasher launched a half dozen torpedoes at the fat target and again was jolted as two more faulty warheads detonated within seconds. Two minutes and 27 seconds later, one of the four operative torpedoes slammed into the tanker.

Surfacing, Laughon saw a tanker bolting south at full speed. Yelling for all-ahead, he set out to attempt to pull ahead of the oiler, turn, and fire from broadside in the classic end-around attack stratagem.

Passing the blazing Hakko Maru, hit minutes earlier by Bluefish, Rasher reached her desired position and swung around to line up her aft tubes. After firing four torpedoes from 11/2 miles, the submariners listened intently. Seconds later, two of this spread exploded prematurely, but not quite two minutes after that the other pair struck squarely. The unfortunate tanker went up like a Roman candle, hurling burning crude oil and shreds of the vessel’s hull hundreds of yards in every direction. Twenty minutes later, nothing was left on the surface except a burning oil slick.

It turned out this vessel had been the same Kiyo Maru that Rasher had hit moments earlier. The damaged ship Laughon had almost torpedoed had been Porter’s sinking kill, Hakko Maru, which in the gloom Laughon mistook for Kiyo Maru. A third tanker in this strangely unescorted convoy escaped after taking Rasher’s first shot.

After a brief conference in which they compared notes and confirmed each other’s kills (Porter’s Hakko Maru was 6,046 tons), the skippers declared the chaotic, profitable engagement finished.

Rashers‘s Next Tour

Late on the night of January 11 Laughon missed with a four-shot spread fired at a small freighter convoy off Phan Rang. One of the fish exploded so soon after leaving the tube that the concussion broke lightbulbs in the sub and knocked paint chips from the superstructure.

Because the mines had taken up so much room, Rasher had been unable to carry a full inventory of torpedoes on this patrol and now had just one left. When the skipper informed COMSUBPAC (Pacific Submarine Command) of the situation, he was ordered back to Fremantle, Australia. In Buton Passage on the evening of the 17th, Laughon fired his last shot at a 10,500-ton Aikoku-class cargo vessel, and this torpedo exploded only 20 seconds after firing. On January 24, Rasher docked in Fremantle’s harbor.

While his crew rested and his boat was serviced, Laughon learned his next tour was for the Surabaya-Ambon lanes north of Bali. After patrolling there, Rasher was to shift her attention to the Celebes Islands, north to the Talaud chain, returning via the Molucca, Ceram, and Banda Seas. Subs returning from these sectors reported few unescorted targets and that Japanese destroyers were doing a better job of antisubmarine attacks. Also, there had been a noticeable increase in air patrols.

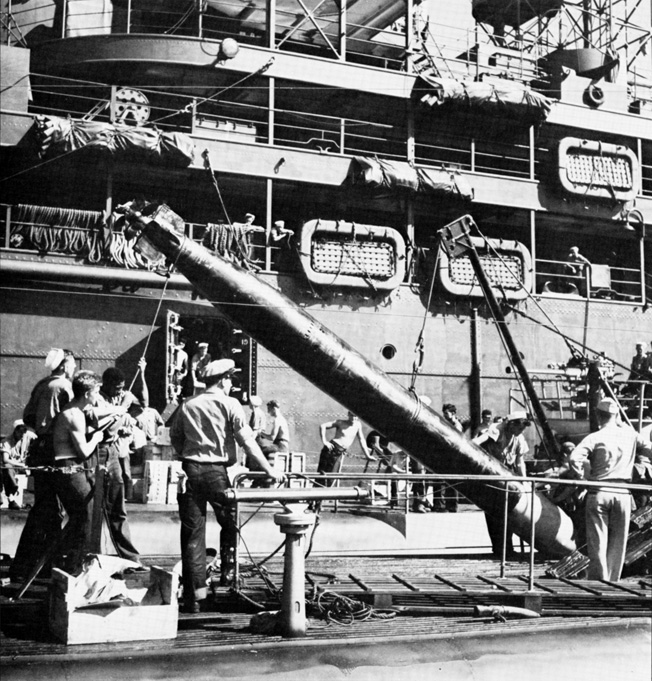

This perilous situation was one Laughon would have to expose his crew to even more than normally, for he was instructed to also photograph convoys, their escorts, and coastal fortifications. On February 19, Rasher set out on her third war cruise armed with new, improved Mark-14 torpedoes.

“Hogging the Show”

On the 24th, Laughon received instructions to rendezvous with the submarine Raton, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. James W. Davis, and search the Raas Strait for a pair of supply ships that were expected there on the evening of February 25. Early that morning, Rasher and Raton met. After making plans to cooperate, they commenced hunting just before 5 pm.

At 5:30, lookouts aboard Rasher spotted the masts of the cargo carriers. As he worked his way ahead of the ships, Laughon radioed Davis to inform him of the convoy’s position. Moments after 7 pm, Rasher shot four improved torpedoes at the lead target an instant before slewing to the right to set up on the second mark. By the time her killer was on this new heading, the 6,200-ton target had been ripped wide open. Four minutes later she sank. Like an earlier victim of this sub, her name was Tango Maru.

Meanwhile, Laughon was receiving a transmission from Raton, informing him that Davis was ready to help out in any way needed. Rasher and her men needed no assistance as they lined up on 4,797-ton passenger-freighter Ryusi Maru and fired four more fish. One impacted amidships, a second under the stack, and a third blasted open the stern. Ryusi Maru was seriously overloaded, her Plimsoll line well under water. Weighty and savaged as she was, it is surprising she took six minutes to sink.

A couple of small patrol boats had been escorting the freighters, and they now searched for survivors in the heavy seas rather than trying to attack the Americans. The subs did not interfere with the lifesaving operation and steered off in different directions after Laughon delightedly radioed an apology to Davis for “hogging the show.”

Bombers Overhead

The next morning, Rasher arrived off Cape Mandar and steered through the Makassar Strait at a leisurely clip. There was little to see for almost a week, but on the evening of March 2, the surfaced submarine passed through a flotilla of small fishing boats whose crews evidently reported her to the Japanese.

Bombers began appearing the next morning. The first one did not see Rasher as her radar man gave enough warning to dive to safety before the warplane appeared, but the next one, at 9:54 am, slipped beneath the radar beam by skimming the waves at 300 miles per hour.

Within 30 seconds, the sub was under and plunging. Two bombs exploded far above her as she passed 120 feet. Laughon wondered if the planes might be covering ship movements. About an hour after the second bomber’s pass, Rasher surfaced and her men broke out binoculars.

Sharp-eyed Seaman First Class Robert Cashel spotted a thin column of smoke on the western horizon at 11:50 am. Freighters were heading southeast, presumably to deliver arms, ammunition, and sundry supplies to the Japanese garrison on the Minahassa Peninsula. Submerging his boat, Laughon ordered full speed in hopes of cutting off the convoy, which had three escorts. The end-around worked, and the Americans caught up with two rows of freighters with a torpedo boat on each side, and one trailing. Overhead was a twin-engine Mitsubishi Ki-21 “Sally” bomber.

“Take Her Deep!”

Approaching from port, Laughon was dutifully snapping photos through his periscope when the targets abruptly veered south. He later wrote in his report that he surmised the enemy had received news of Rasher’s sighting by the planes earlier in the day. The sub was still 8,000 yards from the ships, and it was unlikely it had been spotted.

Turning south with his targets, Laughon waited for dark when the bomber departed to refuel. The hunters surfaced and headed for the convoy at 17 knots but were spotted by gunners on one of the transports and bracketed in a hail of shellfire from the port escort as it peeled off to attack. The boat chased Rasher 10 miles before turning back. Rasher was right behind her. Laughon’s radar had malfunctioned, so he decided to barge directly into the fleet in a surprise assault.

Covered by darkness, the Americans cheekily charged to 1,500 yards from the nearest ship, fired three torpedoes, turned right, and fired three more at the following vessel. As the first spread smashed home, Laughon swung his boat to line up her stern tubes on a third target, but she was too close. The stricken vessel was a troop carrier with masses of panicked soldiers spilling over her railings, and the ship Laughon had hoped to drill next was advancing on him under full steam. She was just 600 yards away and closing. Worse, one of the escorts was on the way, her searchlight playing madly over the dusky, churning seascape.

The second torpedo salvo had missed, but there was no time to worry about it as the ponderous transport bore down on the sub. “Take her deep! 300 feet! Flood negative!” rasped Laughon. The massive steamer‘s crew were rolling depth charges from her decks, and the escort was joining in the barrage. The bombs began detonating as Rasher passed 180 feet, rattling her but doing little damage. Moments later, she was under the thermal barrier and the infuriated Japanese were dropping their charges on sonar ghosts. The corpse of the 6,484-ton Nittai Maru passed Rasher en route to the bottom.

Unconfirmed Kill

By midnight, all was clear topside, and Laughon surfaced his boat. Passing through a flotilla of lifeboats filled with sodden Japanese infantrymen whose comrades had been too panicky to rescue, the submariners headed for the shipping lanes off Balikpapan, where Laughon thought the convoy might be bound.

The Americans found the convoy right where they expected it and aimed two missiles at the closest ship at 3:02 am on March 5. There were still bugs in the works, and both torpedoes ran too deep, streaking harmlessly under the target. The freighters’ crews were still unaware they were under attack, so Laughon turned his back and shot four properly functioning missiles from the after tubes. At least two fish hit, setting off the same pandemonium as the night before.

Plowing through the blazing chaos of explosions, screaming men, and hammering deck guns, Rasher moved clear and loaded her last four rounds, easing back into the combat perimeter where she was opened up on by two escorts. Laughon hurriedly drew a bead on a third ship, fired the final missile quartet from long range, and bellowed for a withdrawal. A full four minutes later the Americans heard four distinct warhead detonations.

By 6:30, Rasher was clear of pursuers and received a radio message to return to Darwin for reprovisioning and a quick return to her hunting grounds. While in port the crew were infuriated to learn that since they had not actually seen their victims of the March 5 attacks sink they would not be awarded kill credits for this engagement.

Two Kills, One Credit

By March 9, the sub was again outbound. She had just passed the barrier islands bordering Timor when a crucial radio message was received. Navy codebreakers in Hawaii suspected that Admiral Mineichi Koga was assembling a task force of aircraft carriers, battleships, heavy cruisers, and destroyers at Surabaya, Java. U.S. Admiral Ralph Christie was concerned that, being just 1,000 miles from the Australian mainland, this new anchorage was the last stop before a possible attack on Fremantle-Darwin.

Christie ordered Lt. Cmdr. Chester Nimitz, Jr., son of the Pacific Fleet’s commander in chief, to patrol the approaches to Lombok Strait in his sub, Haddo, and watch for a major sortie. Nimitz’s radar picked up several large ships at long range, but Haddo was unable to pull within visual range.

Laughon was ordered to turn west and take up a position above Lombok Strait in case Koga’s fleet came that way. If it did, Rasher was to fire a few shots and then sound the alarm. By March 12, Laughon and his sub were at their post.

They spent the next two weeks dodging swarming antisubmarine air and sea patrols, and on the 19th uncorked a four-torpedo spread at a Japanese sub. All four missed, and both boats hastily quit the area before things got testy.

There was still no sign of Koga’s armada, but on the morning of March 27 sonar detected a distant line of vessels. It was not the anticipated task force, but a four-ship freighter convoy escorted by four minesweepers. Sandwiching the zigzagging targets between Rasher and Panerungan Besar Island, Laughon approached with his standard resolute aggression and fired six torpedoes at the first two ships in the line. One missile hit the first vessel, 2,750-ton Nichinian Maru, just behind her stack. Thirteen seconds later three more torpedoes mortally wounded the second target. At this point, Nichinian Maru’s cargo of ammunition ignited and blew her to bits. The other vessel went under about an hour later.

After the escorts fruitlessly depth charged, Laughon crept close in an attempt to snipe at the remaining pair of freighters, but three bombers suddenly appeared, and the submariners prudently backed off and made their escape through Lombok Strait.

Despite seemingly incontestable proof via photographs taken through the periscope that Rasher had scored two kills in this encounter, postwar research based on intercepted Japanese radio traffic credited Laughon and his crew with sinking only one ship, the Nichinian Maru, in this battle.

The Battle of Buru

On March 29, the hunters were delighted to be ordered back to Fremantle. The Koga crisis never materialized. When the Allies assaulted the Marshall Islands, Koga abandoned any plans he may have had for attacking Australia, ordering his forces to forsake their bases on Truk and relocate west.

Before the next patrol started, Laughon was instructed to move his boat to Darwin for final preparations. On May 8, she weighed anchor and steamed north into her favorite hunting grounds.

Two days later, Laughon deftly slipped his boat into the middle of a convoy off Buru. He drilled two torpedoes into a tanker and one into her escort, setting the oiler ablaze and crippling her guardian. Still, so many of Rasher’s torpedoes missed in this shootout that she was out of them by the time it was over. Although the tanker, 1,074-ton Choi Maru, did not sink, her vital cargo of crude oil burned to the last drop.

Following what his crew called the Battle of Buru, Laughon received wireless instructions to open sealed orders. He was to take up a position in the Java Sea off Surabaya. Warplanes from the carriers USS Saratoga and HMS Illustrious would be making an attack on Surabaya on the 17th, and Rasher was one of eight submarines detailed to stand by and pick up downed airmen.

No planes went down in Rasher’s area, and after the raid she was ordered back to Darwin for fuel and ammunition. She arrived on May 21, and set out again the same day on a foray through the Molucca Passage.

Turning the Japanese Back from Biak

On the evening of the 29th, right after spectacularly popping open the 2,601-ton, gasoline- laden freighter Anshu Maru, Rasher received a critical message. Sister subs Bluefin and Cabrilla had discovered a large Japanese task force headed for the island of Biak, which General Douglas MacArthur’s forces were desperately trying to wrest from the Japanese. If the Allies could take Biak, they would have a precious base for their bombers that was just 600 miles from the Palaus chain. Laughon set course for the Talaud Islands, which were on the fleet’s last reported heading, but found nothing. On June 2, he was ordered to Davao Gulf and late that night came across part of the flotilla.

The Japanese were moving too fast for Rasher to get in range, but Laughon’s wireless report killed the suspense as to the fleet’s whereabouts. Then the rest of the Biak-bound attack group appeared. Laughon again sounded the alarm, and was sighted by the warships. Realizing the essential element of surprise was gone, the Japanese gave up on the operation and returned to Mindanao. Rasher’s mere presence had helped to assure victory on Biak.

The submarine returned to the Celebes Sea. On the afternoon of June 8, the crew celebrated the first anniversary of their submarine’s commissioning by sinking the 4,000-ton tanker Shioya Maru.

On the 14th, Rasher sprayed torpedoes into another Celebes convoy, sinking the 3,183-ton transport Koan Maru. At noon the next day, Laughon put his last two missiles into what he thought was the 5,072-ton Kizan Maru outside Ambon Bay, then dove to escape the pair of sub chasers escorting her. Just before the depth charges started going off, the Americans heard a protracted, rumbling explosion that led them to assume they had polished off another victim, but when they later surfaced they were mystified to find nothing on the rain-lashed surface.

Despite the whole crew hearing the torpedoes explode, followed by what sounded like a magazine or a fuel hold blowing up, Laughon decided to not claim a kill in this latest engagement. On June 23, Rasher arrived at Fremantle.

Almost Lost at Sea

Christie was unwilling to risk his prized hunter on another patrol, so he detached Willard Laughon from Rasher’s complement and assigned him to the staff of the 7th Fleet’s Submarine Command. Laughon arrived at his new posting a celebrity, having commanded one of the most famous subs in the Pacific.

Rasher’s new skipper was veteran submariner Commander Hank Munson. With two Navy Crosses from earlier action in submersibles, he was the sort of fire-eating leader this untouched crew needed. His performance would be devastating on the coming patrol.

As Japan’s war fortunes steadily soured, U.S. subs ranged ever closer to the Home Islands in search of a shrinking assortment of targets. With the Allied invasion of the Philippines looming, Rasher and Bluefish were ordered to the South China Sea off Luzon.

Traveling separately, the subs embarked for their hunting grounds on July 29, 1944, arriving August 4. As soon as he reached the rendezvous point (Bluefish arrived a few hours later), Munson found a juicy target in the 4,739-ton passenger-cargo ship Shiroganesan Maru. He approached by cutting just 700 yards directly in front of two sub chasers escorting the target. This maneuver was so brazen the Japanese were not watching for it. Drawing a bead from perfect right angles at 1,350 yards, Munson fired a half dozen fish, then dove to escape in advance the coming depth charging. The undersea mariners heard five distinct hits followed by the metallic screeching of a ship breaking up.

Moments later, Rasher was almost lost through human error. A rookie torpedo man held two of the forward torpedo room’s poppet valves open too long after the missiles were launched, and seawater instantly cascaded into the boat’s fore. Dangerously front heavy, Rasher nosed over and commenced an almost vertical plunge into the mile-deep South China Sea basin. Designed to safely go no deeper than 312 feet, she dove to almost 500 feet before her men were able to level her via precise pumping and blowing.

The Most Productive Torpedo Volley in History

On August 8, Rasher and Bluefish joined forces. Munson and Bluefish’s skipper, Commander Charles Henderson, laid plans that would make this cruise one of the greatest Allied naval victories of the war. First the pair of sharks had to weather a week-long typhoon. The tempest finally began to clear on the 17th, and Munson received a radio report of a large convoy headed his way from the north. Before contact could be made, the weather closed in again, making searching doubly difficult, but at 10:09 pm radar detected the quarry.

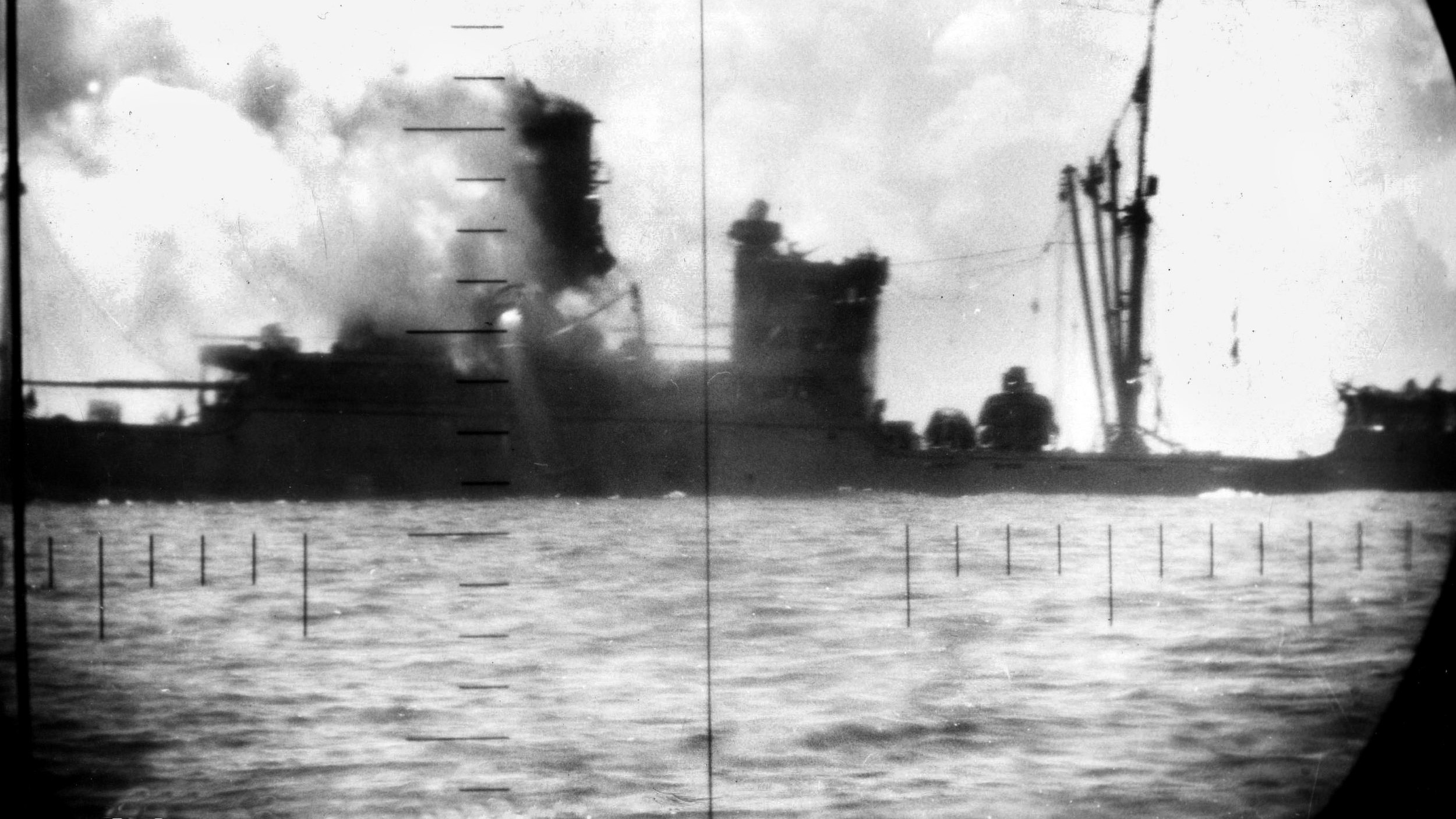

A two-column flotilla of more than 20 Japanese ships was headed directly at Rasher (she had become separated from Bluefish during the storm). Through a moonless downpour, Munson bore in, swung around, and fired two stern torpedoes into a gasoline-filled tanker that erupted into a blinding, 1,000-foot fireball. As escorts opened confused salvos on empty ocean and each other, Munson lined up on the biggest target on his radar screen, shot his six bow tubes at her, swapped ends, and fired four after missiles at the next largest, then pulled back to watch the results.

In perhaps the most productive single torpedo volley fired by any submarine in history, three of the torpedoes from the fore tubes smacked into their mark and set her alight. This first spread’s fourth shot missed its target, but seconds later lucked into an unseen ship beyond the first one. Moments after this, three of the aft fish plowed into the starboard hull of the aircraft carrier Taiyo. The last stern torpedo missed the carrier but hit another previously unnoticed vessel behind Taiyo. Munson later described the escorts as “rushing around like rats in a cage,” as their crews searched for what they may have thought was more than one sub.

Taiyo sank like an ax head, and at 11:27 another line of supply vessels blundered into Munson’s path. He fired his last four bow missiles at the leading ship, turned and shot the final pair of stern fish at the second vessel. Three of the fore torpedoes hit their mark, an ordnance ship that exploded with such violence it illuminated the storm-lashed Luzon coast like midday. The fourth bow shot malfunctioned, veered right, and caught a transport 1,400 yards beyond the late ammunition carrier. The after torpedoes drilled a big cargo ship following the first one hit.

52,667 Tons

By this time Bluefish had drawn in range of the now scattered convoy and attacked two tankers that crossed her path while fleeing from Rasher. Also, the American sub Spadefish had been monitoring Munson’s radio transmissions and had hurried to join the fray. She sank a troop transport chased past her by Rasher.

At midnight, Munson prowled his boat back to the scene of the first shots to see if any targets remained. The ship struck by his final bow shot was limping south with an escort. Munson tracked them on radar until the transport disappeared from the screen, presumably sinking. The vessel hit by the two stern torpedoes escaped sinking by grounding herself on a nearby beach. Passing clumps of oil-coated Japanese sailors clinging to overturned life rafts, Munson tracked two more of his cripples as they headed for Port Curimao’s seashore. He hoped to finish them with his deck guns before their skippers could run them aground, but with dawn approaching he refused to become greedy and turned his killer shark for the open sea. The stormy night was over and had brought a great victory for the Americans.

The unfortunate convoy had been designated HI-71 by the Japanese and was effectively destroyed by the Rasher-led attack. The few ships not sunk or crippled turned back, never making it to their assigned destination in the Philippines. The fighting would have been terribly prolonged had the huge haul of soldiers, weapons, fuel, aircraft, and ammunition been delivered.

At the time the submariners did not know the identities of the victims of their devastating nighttime assault. Postwar research fixed Rasher’s kills for the night of August 18-19, 1944, as the 20,000-ton Taiyo, 17,537-ton passenger-cargo ship Teia Maru, 9,849-ton oiler Teiyo Maru, and the ship that ran aground off Port Curimao as the 542-ton freighter Eishin Maru. Rasher and her crew sank at least 52,667 tons on this patrol, if the August 6 destruction of Shiroganesan Maru is included. During that fiery night the Japanese also lost the 6,500-ton tanker Hayasui to Bluefish, and the 9,589-ton troop carrier Tamatsu Maru to Spadefish. During the four-hour torpedo attack the Americans sank a minimum of six ships totaling 64,017 tons and put several more out of commission.

18 Ships Sunk

It was the sort of heroic productivity Rasher had been part of since her arrival in the Pacific, but it was to be a magnificent finale. After her Philippine Sea combat extravaganza, she made her way to San Francisco to be dismantled and rebuilt literally better than new. She later went on a sixth war cruise under Commander Ben Adams, and a seventh and eighth under Commander Charles Nace, but scored no more kills on the target-bereft ocean she had helped clear of the Japanese enemy. Her confirmed tally at war’s end was 18 ships sunk totaling 99,901 tons. Her actual score was almost certainly greater since several of her victims likely went under but were never verified. Other quarry were damaged beyond repair.

Rasher was as sleek and beautiful as she was deadly. Her men loved her, but her demise was much less than she deserved. Relegated to auxiliary and training duties in peacetime, she was eventually decommissioned, cut up, and sold for scrap in 1971.

At least the legacy of this remarkably successful submarine survives. Soldiers of all callings need only to look back on her chronicle for the kind of inspiration that will take them above, beyond and, sometimes, below.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments