By Allyn Vannoy

Allied forces had been fighting their way up the Italian peninsula since landing at Salerno on September 9, 1943. After nearly a year they seemed poised, in late August 1944, to crack the final Nazi defensive line.

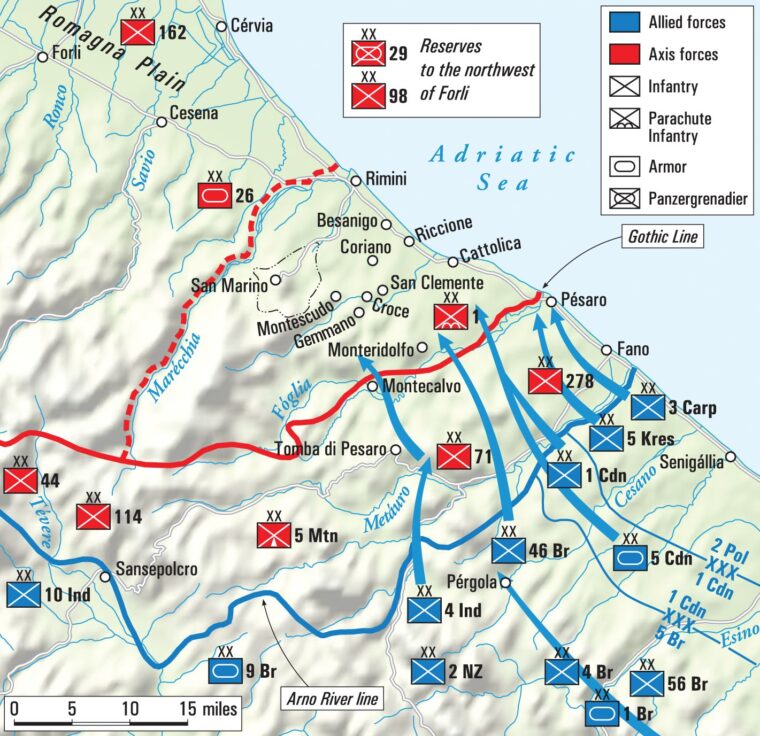

But German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring had other ideas. His last and best hope of halting the retreat of German forces before the advancing Allies was the Gothic Line, a 10-mile-deep belt of fortifications extending from south of La Spezia on the west coast to the Foglia Valley through the natural defensive barrier of the Apennines to the Adriatic Sea between Pesaro and Ravenna on the east coast. Employing more than 15,000 slave laborers, the Germans created more than 2,000 fortified machine-gun nests, casemates, bunkers, observation posts, artillery fighting positions, barbed wire barriers, and many miles of anti-tank ditches.

The assault on the Gothic Line in the autumn of 1944, was launched at the urging of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill with the aim of destroying the German Army in Italy and bringing the Western Allies into the Balkans ahead of the Soviet Red Army.

Following the Allied breakthrough at Cassino and breakout of the Anzio beachhead in the spring of 1944, the Allies liberated Rome while the Germans fell back to the north, establishing one delaying position after another—arriving at the Arno Line in July (running from the west coast of Italy, along the Arno River and into the Apennine Mountains north of Arezzo). This allowed the Germans time to consolidate the Gothic Line.

For the Allies, the Italian Front was secondary to operations in France, as indicated by the withdrawal of seven divisions from the U.S. Fifth Army during the summer of 1944 for Operation Dragoon in southern France. By August 5, Fifth Army’s strength had been reduced from 249,000 to 153,000.

On the afternoon of August 10, senior Allied commanders Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese, commander of the British Eighth Army, and Lt. Gen. Mark W Clark, commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, and their chiefs of staff met to hear Gen. Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 15th Army Group, outline his strategy for dealing with the German forces in Italy.

Alexander’s original plan—as formulated by his Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Sir John Harding—was to storm the Gothic Line in the center of the German front, where most of the Allied forces were concentrated. It was the shortest route to their objective, the Lombardy Plain. But this plan was rejected by General Leese, who did not want to fight alongside General Clark.

General Leese, believing that Kesselring was not expecting a major Allied effort to the east, proposed instead that the Eighth Army attack up the Adriatic coast toward the towns of Pesaro and Rimini, drawing in the German reserves from the center of their line. Fifth Army would then attack in the center of the Apennines north of Florence toward Bologna with the British XIII Corps on the right wing of the attack fanning out toward the coast to create a pincer with the Eighth Army’s advance into the rear of the German 10th Army near Rimini, closing the Germans in a pocket between the Po River and the sea. This would mean that as a preparatory move, the bulk of the Eighth Army would have to be transferred from the center of the line to the Adriatic coast. Such a task would take about two weeks—with intelligence deception being conducted to convince Kesselring that the main attack would be in the center of the front.

General Clark readily agreed, especially on the matter of timing. He could easily hold on his left flank with the few forces he had there and shift the rest to the center for the attack. His only concern was his right flank, where the distance and possible lack of coordination between an American attack toward Pistoia and that of the British XIII Corps on the Eighth Army’s left flank constituted, in Clark’s opinion, a real hazard to the success of operations in the center.

An effective operation against the enemy center, even if secondary, would require that both Clark’s army and the British XIII Corps to be under the operational control of one commander and that their axes of attack be along the shortest distance across the mountains, that is, from Florence to Bologna.

While Clark outlined his reservations, Leese offered to meet his concerns by making Lieutenant General Richard L. McCreery, the XIII Corps commander, a provisional group commander over both X and XIII Corps, but avoided any mention of placing British troops under Fifth Army command.

Clark agreed that the new strategy promised to be effective, the only possible remaining drawback being the delay that would be imposed upon the Fifth Army’s attack.

On August 13, Alexander’s headquarters distributed to the army commanders the plan for the Gothic Line offensive—Operation Olive. General Alexander envisioned turning the enemy Tenth Army’s flank with the Eighth Army. Controlling 11 divisions on a relatively narrow front, Leese’s army was to drive through the Rimini Gap, consisting of approximately eight miles of coastal plain between Rimini and the foothills of the Apennines. Once through the gap the Canadian I Corps and the British V Corps were to deploy onto the Romagna Plain, a low-lying triangular-shaped area cut by many streams and drainage ditches bounded on the south by Highway 9, on the east by Highway 16 paralleling the coast between Rimini and Ravenna, and to the west by Highway 67, extending northeast from Forli on Highway 9 to Ravenna. From the Romagna Plain the two corps were to launch a two-pronged drive to roll up the enemy’s left flank toward Bologna and Ferrara. Meanwhile, the Fifth Army, with three corps controlling nine divisions on an extended front, was to move generally northward from Florence toward the Po Valley.

Both armies were to converge on Bologna and then exploit toward the Po. Light forces, the British X Corps with the equivalent of one and one-half divisions, were to operate in the mountainous terrain that separated the main bodies of the two armies.

Alexander’s resources no longer afforded the luxury of an army group reserve with which to influence the offensive at a critical point. Yet, that seemed no serious problem at the time, for both of his armies were to fight essentially separate battles. But the strategy in this offensive would require the closest cooperation between the two Allied armies and their commanders. Otherwise, Kesselring would once again be able to extricate his forces as he had in June during the retreat from Rome.

Alexander’s decision to shift the main attack necessitated large-scale movement of troops and equipment to the right flank. The movement began on August 15. In eight days, 6,000 tanks, guns, and vehicles had been shifted.

By the last week of August, the Eighth Army was deployed across a 25-mile front: from the coast inland, the Polish II Corps, the Canadian I Corps, and the British V Corps. The entire force included 10 divisions and eight separate brigades. On the coast was the Polish II Corps with the 5th Kresowa Division and the 3rd Carpathian Division in reserve. To the left of the Poles was the Canadian I Corps which placed the Canadian 1st Infantry Division with the British 21st Tank Brigade attached in the front line and the Canadian 5th Armored Division in reserve. To the west of the Canadians was the British V Corps with the 46th Infantry Division manning the right of the line and the Indian 4th Infantry Division the left. In reserve were the British 56th Infantry and the 1st Armored Divisions. In addition, on the left flank of the Eighth Army was the British X Corps with the Indian 10th Infantry Division and British 9th Armored Brigade. Also available was the 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division.

The Germans continued to improve the Gothic Line defenses during the last weeks of August. On the 10th Army front an Italo-German engineer force completed positions in a so-called advance zone (Vorfeld) of the Gothic Lin located along high ridges between the north eastward flowing rivers Foglia and Metauro. Engineers worked on a coastal defense position, the Galla Placidia Line. The line extended in a westerly direction from the Adriatic town of Cattolica 10 miles northeast of Pesaro and then westward for 10 miles to the eastern boundary of the neutral city-state of San Marino. From its northwest corner the line continued seven miles northwest through the town of Sogliano to the Savio River three miles to the west and then along the Savio Valley northeast to the Adriatic 10 miles south of Ravenna.

Although the line was primarily intended as a defensive zone against an attack from the sea in some sectors, especially between Cattolica and the Savio River, it could also be used as a switch position for the Gothic Line. Even though a switch position designated Green Line II had been reconnoitered about eight to 10 miles behind the Gothic Line little work had been done on it.

Field Marshal Kesselring had orders to hold the Gothic Line indefinitely. Months of planning and preparation had gone into its construction, and veteran divisions were deployed within it. To their rear lay the rich agricultural and industrial region of northern Italy.

Facing the Eighth Army was the German Tenth Army’s LXXVI Panzer Corps, defending from Pesaro to San Sisto. Initially there were just three divisions—the 1st Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division facing the Polish forces, the 71st Infantry Division, inland on the parachute division’s right, and the 278th Infantry Division on the Corps’ right flank, which was in the process of relieving the 5th Gebirgsjäger (Mountain) Division. The Tenth Army had a further five divisions of the LI Mountain Corps covering 80 miles of front on the right of LXXVI Panzer Corps. This included the 715th, 334th, and 305th Infantry Divisions and the 114th Jaeger Division; the 44th Division was in corps reserve. Two more divisions—the 162nd Infantry Division (Turkoman) and the 98th Infantry Division (replaced by the 29th Panzergrenadier Division from August 25)—covered the Adriatic coast behind the LXXVI Panzer Corps.

In addition, Kesselring had in his Army Group Reserve the 90th Panzergrenadier Division and 26th Panzer Division, available from August 30. When the panzer corps fell back into the Gothic Line, it was to take control of Group Witthoeft’s 162nd Turkoman and 98th Divisions. The 162nd Division had been formed with POWs from the Caucasus and from Turkic land.

The Polish II Corps, which had been halted since August 10 along the Cesano River, prepared to resume its advance as a screen for the assembly of the Eighth Army’s two assault corps. The corps was to cross the Metauro River and establish bridgeheads to be used as jump off points for the main attack.

For five days, beginning on August 18, the 3rd Carpathian and 5th Kresowa Divisions ground steadily forward in the kind of fighting that had come to characterize action on this part of the front. The Poles gradually pushed back the German 278th Infantry Division beyond the Metauro River, and by the evening of August 22 both divisions had drawn up to the river. But bridgeheads over the Metauro, to be exploited in the Eighth Army’s main offensive, remained out of reach.

Troops of the Canadian I and British V Corps moved on August 24 into assembly areas behind the Poles. In hope of achieving surprise and making up for the lack of bridgeheads beyond the river, artillery was to remain silent until assaulting elements had crossed the river. The offensive was to begin an hour before midnight on August 25.

Plans called for both the Canadian I and British V Corps to pass through positions of the 5th Kresowa Division on the left wing of the Polish Corps. Once past the lines, the Polish division was to shift toward the coast and join the 3rd Carpathian Division in a drive on the port of Pesaro. The Polish troops would be pinched out by the advance of the Canadians toward Rimini, while the V Corps protected the Canadian left. Farther west, the British X Corps was to follow up the enemy withdrawal in the mountains.

Rather than withdraw into the Gothic Line’s main zone of resistance, the commander of the LXXVI Panzer Corps had established his divisions along a series of ridges north of the Metauro. Once he had determined that the main British offensive had begun, he intended to fall back into the Gothic Line. Yet, the Germans ran the risk of being overwhelmed before they could retire.

The Metauro River and a succession of parallel ridges and rivers between the Metauro and the Romagna Plain posed obstacles to British operations. Thirty miles separated the Metauro from the Marecchia River, marking the southern edge of the Romagna Plain, the Eighth Army’s objective.

When the Eighth Army attacked on schedule on August 25, both the Canadian I and British V Corps crossed the Metauro against little resistance. An hour later, as the troops prepared to push out from their bridgeheads, the massed guns of 15 artillery battalions fired a covering barrage. By dawn on August 26, the divisions were well beyond the river and advancing steadily behind heavy artillery fire and aerial bombardment.

The Polish II Corps, along the coast, and the Canadian I Corps, on the Poles’ left, advanced toward Pesaro where the coastal plain narrowed. It was planned that the Polish Corps, weakened by losses and lack of replacements, would go into army reserve and the area of the front on the coastal plain would become the responsibility of the Canadian Corps.

By nightfall on the 27th, the Allied divisions had cleared all enemy forces south of the Arzilla River and prepared to continue northwest to reach the Foglia River, last of the water barriers before the Gothic Line. German forces had been taken by surprise, and the paratroopers of the 1st Parachute Division were unable to halt the Allied advance.

Reacting to an August 24 report of an Allied landing in the Ravenna area, Kesselring canceled entrainment of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division for movement to France and ordered a transfer of the 26th Panzer Division from army group reserve to the Tenth Army’s reserve. However, even after learning that the report was false, Kesselring allowed the shift of the panzer division to the eastern sector to continue. Despite the Allied attack in the area of the LXXVI Panzer Corps, Kesselring preferred to wait to see what might develop before reacting to it.

As additional reports of Allied advances along the Adriatic flank reached German headquarters on the 28th, Kesselring concluded that Alexander had launched his offensive. He authorized the withdrawal of the LXXVI Panzer Corps into the Gothic Line behind the Foglia River and enlisted the 26th Panzer Division from the army reserve to back up the Gothic Line defenses in that sector.

That night the Germans opposite the Eighth Army right wing began to fall back into the Gothic Line. Opposite the Eighth Army’s left wing, the LI Mountain Corps withdrew into the mountains.

Late on the 29th, across a 17-mile front, the British and the Canadians reached the crests of the last hills overlooking the valley of the Foglia, while the Polish Corps entered the southern outskirts of Pesaro. That night the last German troops south of the Foglia retired, withdrawing toward strongpoints around the towns of Montecalvo, Montegridolfo, and Tomba di Pesaro.

By August 30, the Canadian and British Corps had reached the German main defensive positions along the ridges on the far side of the Foglia River. During the night assault troops began crossing the Foglia to move at dawn against the Gothic Line.

At Montegridolfo, the British V Corps encountered troops of the 26th Panzer Division. Exposed to the weight of Allied firepower, the panzergrenadiers were unable to hold. Outflanking the eastern anchor of the Gothic Line at Pesaro, the Polish Corps forced the Germans to withdraw on September 2.

The Canadian Corps had taken Tomba di Pesaro to open a gap between the 26th Panzer and 1st Parachute Divisions and to pinch out the Polish II Corps against the coast during its advance. On the Canadian left the 46th Division of V Corps kept pace. General Leese ordered the British 1st Armored Division forward to join the V Corps and follow up the German withdrawal.

On September 2, the 29th Panzergrenadier Division was ordered to close the gap between the 1st Parachute and 26th Panzer Divisions. In turn, the corps reserve, the 98th Division, was ordered forward to help close a second gap that had developed between the 26th Panzer and 71st Divisions. Along the coastal sector held by the 1st Parachute Division, a blocking position was to be created using elements of the 162nd Turkoman Division with two artillery battalions in support.

After fighting for over a week the troops of the LXXVI Panzer Corps were close to exhaustion.

Kesselring intended to establish a new line along the Coriano Ridge, just before the Romagna Plain. When, on the afternoon of September 2, the Canadian Corps burst from a small bridgehead beyond the Conca River in the direction of the ridge, an imminent breakthrough was expected. But mixed in with reports of progress were indications of growing resistance. To beat back a tank-led counterattack, the Canadians asked for assistance from the 46th Infantry Division, whose troops crossed the corps boundary to help drive the enemy from high ground overlooking the Canadians’ left flank. In the center and on the left of the V Corps, the 56th and 4th Indian Divisions had been advancing slowly against the German positions in the Apennine foothills and were lagging behind.

Leese ordered the 1st Armored Division into action to seize what appeared to be the keystone of the German position—the village of Coriano.

After leaving its assembly area south of the Foglia, the armor found poor traction on the rain-soaked trails leading to the front, causing vehicles to break down and slowing others so that they did not reach the south bank of the Conca River until late on September 3. It wasn’t until mid-morning the next day that the first tanks began passing through the area of the 46th Infantry Division.

The armor had to manage for itself as the 46th Division had not yet captured the planned jump-off points just over two miles short of the Coriano Ridge. The tankers had a five-hour fight just to reach their starting line.

At the same time, taking advantage of the Germans’ lack of manpower the Canadians advanced the 1st Infantry and 5th Armored Divisions, disrupting the German defenses and by September 3 had advanced 15 miles to a second defensive line running from the coast to near Riccione. The Allies were close to breaking through to Rimini and the Romagna Plain; however, the LXXVI Panzer Corps withdrew in good order behind the line of the Conca River. Fierce resistance from the Corps’ 1st Parachute Division supported by intense artillery fire provided by the 26th Panzer Division brought the advance to a crawl.

By nightfall the assault had bogged down a mile short of the Coriano Ridge, while fire from the ridge also brought troops of the Canadian I Corps to a halt. The delays had given the Germans time to bring up tanks and assault guns, and the moment when a breakthrough might have been achieved had passed.

Three more days of effort to gain the ridge failed as the 29th Panzergrenadier Division was committed into the gap between the 1st Parachute and 26th Panzer Divisions.

A week of heavy rains brought flash floods that washed out tactical bridges along inland roads, leaving only the coastal highway for supporting troops beyond the Foglia River. Until the flooding receded, operations of the Eighth Army were brought to a near standstill.

The first battle for Coriano commenced as the Royal Canadian Regiment attacked Riccione, while elements of the 11th Infantry Brigade, 5th Canadian Armored Division, supported by tanks of the British 1st Armored Division, attacked the village of Besanigo, southwest of Riccione. After a trek of more than 50 hours, exhausted tank crews of the 2nd Armored Brigade, 1st Armored Division, were ordered to attack the Coriano ridge but were delayed until sunset on September 4. Fighting extended from Coriano to Croce, exacting a heavy toll. At the end of the first day only 79 tanks out of 156 Shermans deployed (three battalions) were still fit for battle. The fighting continued for two days with gruesome losses on both sides along the front from Riccione to San Savino. As the first battle of Coriano came to an end, the Germans had managed to hold back the Eighth Army.

Leese decided to outflank the Coriano ridge positions by driving west toward the towns of Croce and Gemmano to reach the Maranon Valley, which curved behind the Coriano positions to the coast some two miles north of Riccione.

As the pressure imposed by the Canadian attack had put the LXXVI Panzer Corps in a crisis, the Germans considered withdrawing 10-15 miles to the designated “Yellow Line” along the Marecchia River north of Rimini. Such a decision could have meant an open road to the Romagna Plain, from Bologna to Revenna, for the Canadians. But the German command decided to make a stand at Gemmano (the action later referred to as “Cassino of the Adriatic”).

As the first battle of Coriano neared an end, the 46th Division bogged down on the hills around San Clemente with the 56th Division covering its left flank. On September 4, the 167th Brigade, 56th Division, captured Montefiore Conca and launched a reconnaissance to the slopes of Gemmano.

During the night of September 4, the 56th Division moved toward Croce with the 167th and 168th Brigades supported by tanks of the 7th Armored Brigade. The sector was defended by the German 290th Infantry Regiment, 98th Division, and the 100th Gebirgsjäger Regiment.

Between September 4 and 13, the 56th Division and then the 46th Division were engaged in heavy fighting in the vicinity of Gemmano. The battle for Gemmano was one of the bitterest fights of the Italian campaign. Four attacks were necessary to push the German defenders out of their positions. The 100th Gebirgsjäger Regiment’s casualties were estimated at more than 2,400. British losses for the units that took part in the action averaged 100 to 150 for each battalion.

While fighting continued at Gemmano, Leese decided it was time for a second attack on Coriano, still held by the Germans after stopping the first assault on September 5. In a meeting with the commanders of the British V Corps and Canadian I Corps, it was decided that Coriano should be the target for the 5th Canadian Armored Division while San Clemente was to be taken by the British 1st Armored Division.

After a bombardment by 700 pieces of artillery as well as bomber strikes, the two divisions launched their attacks on the night of September 12 and two days later the fight for Coriano was over.

In the meantime, to the north on the other side of the Conca Valley a similarly bloody engagement was being fought at Croce. The German 98th Division held its positions with great tenacity. It took five days of constant fighting, often house-to-house and hand-to-hand before the British 56th Division captured Croce.

Also on September 14, the remnants of the German forces, near collapse, were assisted by a change in the weather. Several days of heavy rains made rivers and streams impassible to heavy equipment and halted Allied air support operations. Moreover, the Indian 4th Infantry Division was halted by artillery fire on the Ripabianca Ridge. This allowed the Germans to reorganize and restore some fighting capability as they established positions along the Maranon River running from San Marino to Riccione.

Meanwhile, with the towns of Croce and Montescudo secured, the left wing of the Eighth Army advanced to the Maranon River and the frontier of tiny San Marino. The Germans had occupied neutral San Marino over a week earlier to take advantage of the heights on which the city-state stood. By September 19, the city was isolated and fell to the Allies at relatively little cost. Three miles beyond San Marino lay the Marecchia Valley running across the Eighth Army line of advance to the coast at Rimini.

On the right on September 20, the Canadian I Corps broke through the German positions along the Ausa River, opening the way to the Lombardy Plain. The following day the Corps’ 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade and the New Zealand Motor Battalion entered Rimini as the Germans withdrew from their positions on the Rimini Line behind the Ausa to new positions along the banks of the Marecchia.

Kesselring’s defense had won enough time for the onset of the autumn rains. Progress for the Eighth Army became extremely slow as heavy rains turned roads into quagmires, creating a logistics nightmare. The plains became swamps as the Eighth Army found itself confronted by a succession of swollen streams running across its line of advance. These conditions prevented Eighth Army’s armor from exploiting any breakthrough, and the infantry of the British V Corps and Canadian I Corps, joined by the 2nd New Zealand Division, had to grind their way forward while the Germans withdrew beyond the Marecchia to the Uso, a few miles beyond Rimini. Positions on the Uso were forced on September 26, Eighth Army reaching the next river, the Fiumicino, on September 29. Four days of heavy rain forced a halt—V Corps being fought out and requiring major reorganization.

Since the start of Operation Olive, Eighth Army had suffered 14,000 casualties. As a result, battalions were reduced from four to three rifle companies. The LXXVI Panzer Corps had suffered an estimated 16,000 casualties. Though the Eighth Army’s offensive had penetrated the Gothic Line, it had failed in its mission to destroy the German Tenth Army or break through to the Lombardy Plain. The Allies would be held on this line until the following spring.

Author Allyn Vannoy has written extensively on a variety of topics related to World War II. He resides in Hillsboro, Oregon.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments