By David Alan Johnson

At St. Paul’s Cathedral, the rooftop lookout telephoned the cathedral control center at 6 pm to report that air raid sirens were sounding off to the southwest. George Garwood, a member of St. Paul’s watch, received the call and told the patrol he would be right with him. Before Garwood could put on his axe belt and helmet, the lookout phoned again to say that he could see incendiary bombs bursting in Southwark, on the other side of the River Thames. By the time Garwood reached the roof, the local sirens were sounding and fire bombs were falling on the cathedral itself. The German bombers had arrived overhead with much less warning than during any previous raid.

This was the third air raid in a week, which was actually much lighter than the bombing had been in September and October. After the Blitz had begun on the night of September 7, 1940, the Luftwaffe bombed London every night for 57 nights. But because of the weather, the German bombers had not been as aggressive in recent weeks. The raid of the previous Sunday, December 22, 1940, was only a light “nuisance” raid, and had not even made the front page of most daily newspapers.

A Fire Bliz on London

Residents of London tried their best to be blasé about the raids; after three and a half months, they were more resigned to the nighttime bombings than bored by them. Had they known what Adolf Hitler had in store for them on this particular night, Sunday, December 29, they would have been a great deal more anxious.

Tonight’s raid had been ordered by Hitler himself, in retaliation for an RAF bombing attack on Berlin on December 20. Since then, fog and rain had shut down the Luftwaffe’s bases in northern France, which prevented a maximum effort against London. Now, it looked as though the weather would clear long enough to give the Germans their opportunity.

The commander of Air Fleet Three, Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, was not very enthusiastic about this attack, in spite of Hitler’s directive. The rain and overcast appeared to be breaking up, but the weather reports were predicting that a storm front would close in on the French airfields before morning, which would interfere with Sperrle’s planned attack. The clouds that covered France would also put London under heavy cloud cover, making accurate bombing a problem.

Weather problems or not, Sperrle had his orders. The planning session at his suite in the Hotel Luxembourg, his headquarters in Paris, did not last any longer than usual. As it was outlined, the Sunday night attack would be launched in two waves. The first wave would be carried out by about 140 bombers, which would carry mainly fire bombs. The small incendiaries would set hundred of fires within the target area, creating a brightly lit aiming point for the second attack. The second wave would be carried out by about the same number of planes, but these would drop loads of 550-pound high explosive bombs. The object was to destroy anything that had not already been burned down by the first wave. Close to 300 sorties would be flown, making this the heaviest attack against London in well over a month.

Target: St. Paul’s Cathedral

The fire blitz was not a new tactic. The foot-long incendiary bombs had been used many times, but always mixed with loads of high explosives. The first time they had been used exclusively was on December 22, exactly one week before, against Manchester. Thousands of the small but effective incendiaries had burned out entire sections of the city in only a few hours. On Monday morning, people on their way to work watched firemen as they tried to bring hundreds of fires under control.

Because the fire bombs had worked so well against Manchester, Sperrle decided to use the same tactic against London. The target he chose for the attack was the City of London, the ancient “square mile” that surrounds St. Paul’s Cathedral. The City district was probably best known for its banks and the Royal Exchange, along with picturesque churches and St. Paul’s itself, built by the famed architect Sir Christopher Wren. The City also had its share of military targets, all rated top priority by the Luftwaffe. The Wood Street Telephone Exchange and the London Telephone Service, with its overseas lines, and the General Post Office telephone and telegraph services were important enough to rate pinpoint attacks as separate targets. The district’s six railway stations had also been marked by the Luftwaffe, along with its bridges across the Thames. All of these were within walking distance of each other.

Another factor that made the City such an inviting target was that it was so vulnerable to fire—the London Fire Brigade had labeled it a fire zone years before. The district was filled with old, flat-roofed buildings that were packed with books, textiles, and other flammable items. Paternoster Square, just to the north of St. Paul’s, was the heart of the bookselling and publishing industry; over five million volumes were stored within that confined area. One London fireman called these old places “torches looking for a light.” A few well-placed fires could spread beyond control before the fire brigade could do anything about them.

Also, the 29th was a Sunday, which meant that few people would be on hand to deal with the fires while they were still small and easy to extinguish. If the weather held, this raid might be the most destructive attack on London since the Blitz began.

“Fire Raisers”

In spite of the cloud cover over London, Field Marshal Sperrle could be certain that one of his units would find and bomb the target. The attack would be led by Kampf Gruppe (Bomb Wing) 100, an elite pathfinder unit staffed entirely by handpicked pilots and crews. Nicknamed the “Fire Raisers,” KG 100 was famous throughout the Luftwaffe for having the very best pilots and crews and was commanded by the veteran pilot Hauptmann (Captain) Friedrich Aschenbrenner. Its job was to drop clusters of incendiary bombs on targets at the beginning of a raid, creating a brilliant bull’s eye for the rest of Air Fleet Three. The City of London, with its jumble of old buildings, was tailor made for them.

Even the unit’s aircraft were unique. The Heinkel He-111 bombers flown by KG 100 were equipped with the so-called “X-apparatus,” an electronic device that led the bombers to their assigned target even on the darkest or cloudiest of nights. The apparatus picked up a high-frequency radio beam, which was transmitted by the Luftwaffe Signal Corps from a station on the Normandy coast. The beam was aimed to pass directly over the assigned target. The bombers of KG 100 simply followed the beam to the target.

This primary beam was intersected by a second radio beam, which was broadcast from a station farther down the coast, crossing the “X.” When the aircraft crossed the second beam, the bomb aimer received a signal that he was directly over the target and toggled his load, usually with remarkable accuracy.

The first time that KG 100 used the X-apparatus had been on the night of November 14, 1940, against Coventry. The fires started on that night set the stage for one of the most intensive bombing raids against Britain. Following the Coventry attack, the German Propaganda Ministry coined the word “coventrised,” meaning “burned to the ground.”

Flames Over St. Paul’s

Aschenbrenner and the other 19 He-111s of KG 100 left their base at Vannes, on the south coast of the Brittany peninsula, at 5:40 pm. At 6:05, the bombers arrived over the City of London and, prompted by the X-apparatus, dropped their canisters of incendiaries. Because they flew at a height of only 6,000 feet to avoid early detection by British radar, the Heinkels arrived with much less warning than usual. The fire bombs did their job with alarming efficiency, starting hundreds of small but scattered fires within the space of a few minutes.

When a fire bomb landed on a roof or struck the pavement with a metallic crack, its magnesium core burst into life. A shower of glittering white, molten splinters spewed out in a radius of about 10 feet. The few air raid wardens and roof spotters on duty on this Sunday night stared as dozens of dazzling white sparklers suddenly jumped out of the darkness. For every bomb that burst harmlessly in the street or on a rooftop, at least one pierced a slate roof and began doing its work inside the City’s old buildings. Magnesium reaches a temperature of 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit. At St. Paul’s Cathedral, roofspotters watched as the textile and publishing firms of Paternoster Square were pelted with a rain of the foot-long bombs. Within 15 minutes, the book depositories and textile warehouses were already blazing ruins.

Several thousand feet above the clouds that covered London, Aschenbrenner could see a translucent glow through the dense overcast. The rest of Air Fleet Three also saw the reddish patch in the cloud and dropped their own bomb loads on this aiming point. With each fresh load of incendiaries, punctuated by an occasional 550-pound high-explosive bomb, the fires raging within the City spread and intensified.

A Miracle or Gravity?

By 7:00, only 55 minutes after KG 100 began the attack, three separate fire zones had broken out. The largest, about three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide, surrounded St. Paul’s Cathedral. From the cathedral roof, George Garwood could see the central telephone exchange burning out of control “without a bucket of water to put on it.” As Garwood and the other members of the firespotting team were only too well aware, the cathedral was also in danger. The staff at The Daily Telegraph building on Fleet Street watched as a hail of the two-pound bombs glanced off the cathedral’s dome.

St. Paul’s was far from doomed, although it was in great peril. The cathedral watch stayed out on the roof to take care of burning debris from nearby buildings and put out the sparks with wet sacks. At 6:39, the control center received a telephone call from Cannon Street Fire Station. The firehouse switchboard reported that the dome was on fire.

At the cathedral, a team was sent to investigate. They discovered that an incendiary had punched halfway through the dome’s outer lead covering, sputtering and smoking, with its tailfins jutting out. The bomb was going to be a bit awkward to get at, but it did not pose any serious threat. Even if it burned its way through and fell inside the dome, it could easily be smothered before it could do any damage.

From outside the cathedral, however, the brilliant light of the smoldering bomb made it look as though the dome was burning and that St. Paul’s would soon be in ruins along with its neighbors. One reporter was already at work writing the obituary. “Tonight, the bomber planes of the German Third Reich hit London where it hurts the most—in the heart.” In a nearby City street, Edward R. Murrow of the Columbia Broadcasting System was preparing his nightly report to New York. “And the church that meant most to Londoners is gone. St. Paul’s Cathedral, its great dome towering over the capital of the Empire, is burning to the ground as I talk to you now.”

Up in the dome, the bomb’s intense heat melted the lead skin that held it in place. Before the fire watchers could get close to it, the bomb fell outward of its own weight and landed harmlessly in the Stone Gallery at the bottom of the dome. Whether this was a miracle, as would be claimed, or only gravity is a matter of opinion.

Fighting Flames and Bombers Alike

A short time after the fire crew at St. Paul’s disposed of the dome bomb, firemen from all over London began arriving in the City to deal with the spreading fires. Senior officers in the London Fire Brigade had ordered units from fire brigade posts to concentrate on containing the conflagration. More than 100 fire calls had been received by 7:00; fighting individual fires would be a waste of time, effort, and resources.

Antiaircraft batteries kept up an intensive fire against the raiders, but bursting shells did more damage to roofing tiles and skylights than to the Luftwaffe. The flak was a great morale booster; the bang-banging away at the raiders gave everyone the feeling that they were hitting back. Also, two night fighter units—85 Squadron’s Hawker Hurricanes and 219 Squadron’s Bristol Beaufighters—were on patrol over the capital. Most pilots had trouble finding an enemy bomber, much less shooting one down. The Beaufighter’s AI airborne radar was new and having more than its share of teething pains. It was very sensitive to vibration and completely unreliable. Sometimes the set would work perfectly on the ground, but the vibrations from the fighter’s twin engines would render it inoperable by the time the aircraft reached its assigned altitude. The Hurricane pilots had no radar at all.

Thousands of feet above the brightly burning City, the bombers of Field Marshal Sperrle’s Air Fleet Three continued to unload their clusters of two-pound bombs. Every two and a half minutes, on average, another bomber crossed the English coast and headed on a northerly course toward London. Once over London, the target would have been difficult to miss. The inferno was visible from as far away as the English Channel. Waves of hot air from the hundreds of fires welled right up through the ten-tenths cloud cover, boring a hole in the fleecy white and causing mild turbulence. The heat waves lifted the bombers suddenly higher as they flew over the fires, but not enough to make the bomb aimers miss their mark.

On the ground, the London Fire Brigade did its best, but the fires spread faster than anyone thought possible. A major problem was the lack of water. Abnormally low tides made the River Thames all but useless as a water source—one of the reasons why this particular Sunday was chosen for a major attack on London. Through sheer luck, one of the few 550-pound high-explosive bombs had hit the City’s primary water main, cutting off fire hydrants throughout the district. Sperrle’s strategy—dropping massive numbers of incendiary bombs on the weekend before New Year’s when the tides were at their lowest point—was working beautifully. The second wave, carrying loads of high explosives, would finish off anything left by the fires.

“You Could Read a Paper by it”

The heat was extraordinary at the heart of the inferno. The flames and superheated air crumbled stone walls, made the asphalt roadways burst into flame, and twisted steel girders like so much putty. Inside Moorgate Underground Station, all the aluminum and glass from the light fixtures melted and ran down the walls, forming pools on the concrete platform.

The favorite and most repeated phrase by eyewitnesses of the fire was, “You could read a newspaper by it.” Reporter Hilde Marchant of the Daily Express, astonished by the sight of her shadow on the pavement, opened a newspaper to see if it really was bright enough to read by. She felt certain that someone would say that it was. By the flames on Ludgate Hill, not far from St. Paul’s, she was able to make out every word on the printed page.

The last time this district burned was in 1666, during the Great Fire of London. That fire had begun on September 2 and, fanned by strong winds, raged across the City for four days and nights. What had taken days to destroy in 1666 was now being brought down in a matter of hours.

At about 10 pm, the tide finally started coming in. Water was relayed from the Thames via 3.5-inch fire hoses into 5,000-gallon static water dams that were stationed throughout the district. It was still only a trickle, but a very critical trickle. A few hours earlier, it might have made all the difference.

Firefighting units were still arriving in the City from all over the greater London region as well as the counties surrounding London. They were too late to do anything about the damage that had already been inflicted, but at least they now had water to keep the flames from spreading. The new supply of water was no help to anyone on Fore Street, north of St. Paul’s, where the fire brigade was fighting a losing battle. Buildings along both sides of the street had been burning since about 6:30. There was nothing the firemen could do to save any of them. The air was hot and alive with flying bits of glowing debris as the buildings disintegrated and sent hot embers shooting into the air.

1,400 Fires

More than 1,400 fires burned within the “square mile.” Everything from textile warehouses to medieval churches was being destroyed. One landmark succumbing to the advancing flames was the Guildhall, the City’s town hall, which dated from the 15th century. Besides being a City landmark, Guildhall was also the control center that connected the many fire stations in and around the City with each other. Telephone operators inside the Guildhall stayed on the job even though they knew that the building was on fire. Their log book entries for the night of December 29, 1940, give a terse account of the City’s ordeal, noting the time and nature of each incident. “IB-F” indicates “incendiary bomb—fire.”

No. 1 6.20 Knightrider Street—Queen Victoria Street IB-F

No. 59 6.45 Eastcheap by Mark Lane—“Explosive IBs are bursting all over the place.”

No. 62 6.59 Queen Street by Mark Lane—“Well alight.” IB-F

No. 74b 8.10 YMCA Bldg., 186 Aldersgate St. IB-F “Fire spreading rapidly—nobody in building.”

No. 137 9.10 26/27 Bush Lane – “LFB wanted urgently!” IB-F

No. 171 10.0 12/16 Red Lion Court—“LFB in attendance, IB-F but no water.”

Telephone operators kept the lines open for as long as possible, but by 10:30, it was clear that the building would have to be evacuated. The fire brigade officer in charge ordered the girls to leave Guildhall, telling them there was nothing more for them to do. They left the building and began walking south, past the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, in Guildhall Yard, which was also crackling and flaming.

Second Strike Postponed, Then Canceled

At about the same time that Guildhall was being evacuated, Sperrle decided that the second strike would have to be postponed for a few hours. Every one of Air Fleet Three’s bases had been reporting bad weather for the past several hours. Sperrle’s pilots reported that his plan of using a torrent of 2.2-pound incendiaries against the City had been totally successful—roughly one and a half miles of London was burning brightly. He still hoped that the planned second wave would be able to attack the target with high explosives.

The weather continued to worsen. By midnight, heavy rain had shut down every bomber base in northern France and there was no let- up in sight. Sperrle was thoroughly disappointed, but the weather left him with no choice but to call off the next strike. From his suite in the Hotel Luxembourg, he reluctantly gave the word to his commanders to stand down. The second attack had been cancelled.

No one in London had any idea that the raid had ended. The antiaircraft guns had stopped firing, but there had been lulls in the shooting throughout the attack. Firemen were surrounded by their own world of noise and flame. The fires themselves made their own continuous roar, and over 2,000 fire pumps added to the din. When the all clear sounded at 11:50 pm, the high pitched howl of the sirens was met by a sigh of relief from most Londoners.

There were some who could not bring themselves to believe that it was all over. An auxiliary fireman at work in Southwark was taken completely by surprise when the sirens sounded. He thought that the authorities were sounding an alert to warn of “some new menace—we already had rattles for [poison] gas and bells for invasion.” When the sirens held the high note for the all clear, the fireman was “utterly incredulous.” It was unbelievable that the Germans would miss “the juiciest target in history.” The thought even occurred to him that some fifth columnist might have sent a false all clear to confuse the defenses.

Riding the “Sea of Fire”

Everyone who was not asleep came out of their air raid shelters to have a look at the fires they had been hearing about for the past five hours. A combination of nerves and curiosity brought most people out. A woman living on the very edge of the fire zone was struck by the brightness of the fires. She does not remember any smoke at all, just flames and more flames with the image of a fireman on a ladder stamped upon the red backdrop.

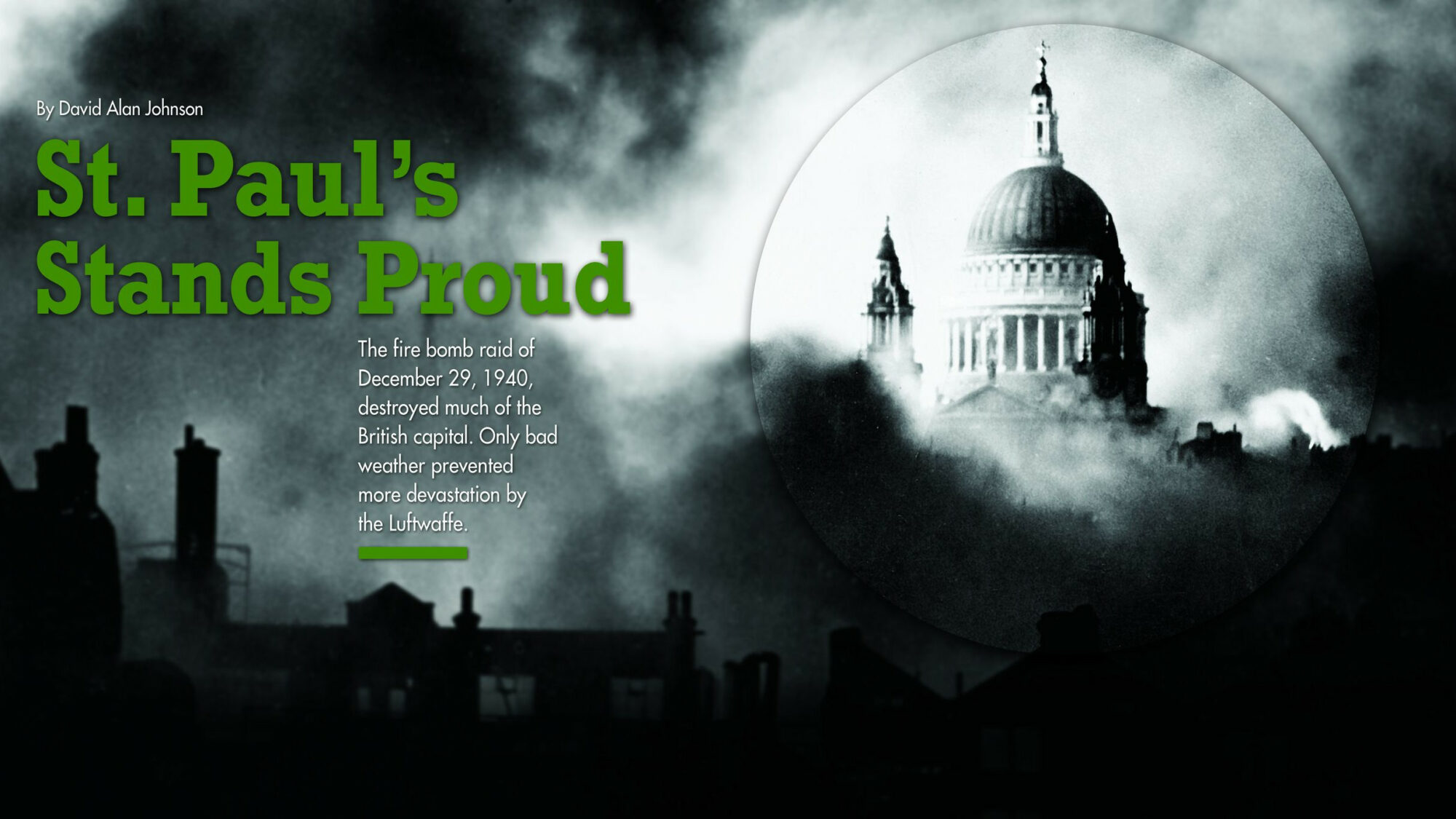

The focus of attention was St. Paul’s Cathedral, the tallest and most brightly lit landmark in the district. “The dome of St. Paul’s seemed to ride the sea of fire like a great ship,” noted a reporter with The Times, “lifting above the smoke and flames …” Onlookers might have been inspired by the sight, but it made little difference to the firemen on duty. Their long night was still far from over.

For most of the fire crews there was no relief, only hour upon hour of holding a pressurized fire hose in sweltering heat and stinging smoke. The relays from the Thames were finally beginning to take effect. By the time Monday morning commuters began making their way into the city, the fires were no longer spreading.

After the Raid

The morning after an air raid always meant chaotic traffic. Even an early start was not much help on this morning. Every road and all the Thames bridges into the ravaged City were closed to automobile traffic. Most people who worked in or near the City rode their usual trains or buses as far as they would go and walked the rest of the way. Many walked for a mile or more, climbing over piles of bricks and rubble and leaking fire hoses, and arrived at their jobs filthy and soaking wet. Clerks and shorthand typists often arrived hours late and were congratulated for having shown up at all.

Thousands arrived at work only to find that their offices or factories had disappeared during the night. St. Paul’s was still unscathed, but hundreds of nearby firms had been destroyed. Many of the displaced workers simply wandered aimlessly about, not knowing what else to do. A crowd gathered outside St. Paul’s, as though hoping some of the cathedral’s charm would rub off on them.

Although wartime censorship would try to keep the damage done to war-related industries a secret—newspaper accounts would emphasize the destruction of ancient churches and historic buildings, including Guildhall—employees of firms within the fire zone could see the damage for themselves.

Probably the most disrupted of the essential war services was the communications network. Telephone and telegraph services were knocked out, including transatlantic lines to the United States. The post office telephones on King Edward Street were a total loss—the building had been burned out by incendiaries and the basement, with all of its transformers, was flooded. Also destroyed was the Central Exchange on Wood Street, along with every other building on both sides of the road. Engineers tried to rig emergency telephones, but this was no help at all. The telephone lines had also been destroyed.

After the Great Fire of 1666 burned itself out, almost all of the old walled City of London was a blackened ruin. On Monday morning, December 30, 1940, the fire damage was not quite as widespread, but entire sections of the City had been destroyed; row upon row of blackened shells and freestanding walls swayed and creaked in the wind. This would remain the largest area of destruction in London throughout the Blitz, and perhaps the worst in Britain.

A Squandered Propaganda Opportunity

Sperrle had no idea what his bombers had done. Reports from the crews mentioned sehr starke Brände, “fierce fires,” in the target area, but these descriptions were too vague to be of any real value to Luftwaffe intelligence. Because all of southern England was still covered by dense clouds, it was not possible for reconnaissance planes to photograph the target. As far as Sperrle was concerned, the previous night had been a total failure.

An official report filed a few days after the raid illustrates the Luftwaffe’s lack of information. “Toward the end of the attack,” the document declared, “there were over one hundred widely spread fires with dense black clouds of smoke, mainly in the City and to the north.” Actually, the incendiaries alone started more then 1,500 fires, with additional outbreaks spread by wind. Because of the limited visibility over the target, the pilots could not see what was happening in the target area.

Sperrle’s opinion was shared by the rest of the Luftwaffe’s high command, as well as by the Ministry of Propaganda. If Dr. Josef Goebbels, head of the Propaganda Ministry, had known about the chaos created by the raid, he would have broadcast a highly descriptive and voluble account of it over German radio. Goebbels was never given to understatement. On December 30, only this routine communiqué was issued: “Strong bomber formations attacked London again last night.”

Intelligence would learn the full effects of the bombing of December 29 when the weather cleared. After seeing the reconnaissance photos, the propagandists would jump into high gear, gloating over the damage and boasting that over 100,000 incendiaries had been dropped. Actually, about 24,000 had been used. But on Monday, they did not even bother with the usual practice of interviewing the bomber crews. Because half the raid had been cancelled, it was not considered important enough to warrant it.

Who was Responsible for the Fires?

The rain and clouds saved the City. Had the second attack been carried out as Sperrle planned, Air Fleet Three’s bomb aimers would have dropped hundreds of tons of high explosives on the brightly lit target. Everything that had not already been burned—military targets and historic sites alike, including St. Paul’s—would have been blasted into rubble. The City of London would have ceased to exist.

In the wake of the fire blitz and the incredible damage that had been done by the small, easily extinguished two-pound incendiary bombs, an outcry of anger and frustration erupted throughout greater London. The outrage was not directed so much at the Luftwaffe as at the landlords and company managers who failed to post roof spotters at their buildings. Outraged letters to newspapers and entries in wartime diaries called for charges of criminal negligence against building owners and managers. Harsher critics simply railed and called names, declaring that the fires were every bit as much the fault of City landlords as the enemy bombers.

A very small minority took a completely different point of view. Architects and forward-looking urban planners almost rejoiced over the loss of the City’s old firetrap office blocks. One commentator wrote that some of the “dreariest and meanest stretches of Victorian office buildings in the whole of the City of London” had been demolished literally overnight, something that would have taken 25 years in peacetime. “The Hun is giving us a priceless opportunity to re-conceive the city on a more rational and liveable plan.”

This might not have been the most widely held opinion, but it certainly was prescient. The face of the City would be changed by glass and steel office blocks that replaced the old Victorian and Edwardian buildings. Entire streets would be paved over to make room for new construction, and only eight of the 17 ruined Wren churches would be rebuilt. For better or worse, the City of London would never be the same after December 29, 1940.

In contrast to the damage to property, loss of life was disproportionately small. Only 163 persons were killed in the bombing and fire, and another 509 were wounded—almost miraculous considering the scale of the attack. The London Fire Brigade’s killed and wounded was also relatively small—12 dead and 250 wounded. Had Sperrle been able to launch his second wave, the toll of dead and wounded would have been many times that number.

Londoners Weather the Blitz

London had escaped the full measure of Adolf Hitler’s wrath this time. But there would be other opportunities, and Hitler would see that each one was exploited to the fullest. The clouds would have to lift sometime, and when they did the Luftwaffe would be ready. London was too large a target and too filled with tempting landmarks and objectives to be missed.

The Blitz against London would continue for another five months, until May 1941, when Hitler turned his attention to Russia. On Monday, December 30, however, the bombing stopped for the time being. A semblance of life returned until the next time the sirens sounded. With the approach of darkness came the threat of another air raid. By 5 pm, it was evident that the bombers would not be back again this night. The sky was still overcast and threatening rain. A City worker made this entry in his diary: “The night turned out to be windy with rain and I was thankful that no warnings were sounded.”

David Alan Johnson is the author of The City Ablaze, which is an hour-by-hour eyewitness account of the December 29, 1940, fire blitz. He resides in Union, New Jersey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments