By Kevin Mahoney

The Russian Army of World War I is comparatively unknown in the West when compared with the other major combatants of that conflict. Accordingly, the uniforms worn by this army are also less well known, but as interest in them among militaria collectors has risen in recent years, a short look at Russian field uniforms of the period is in order.

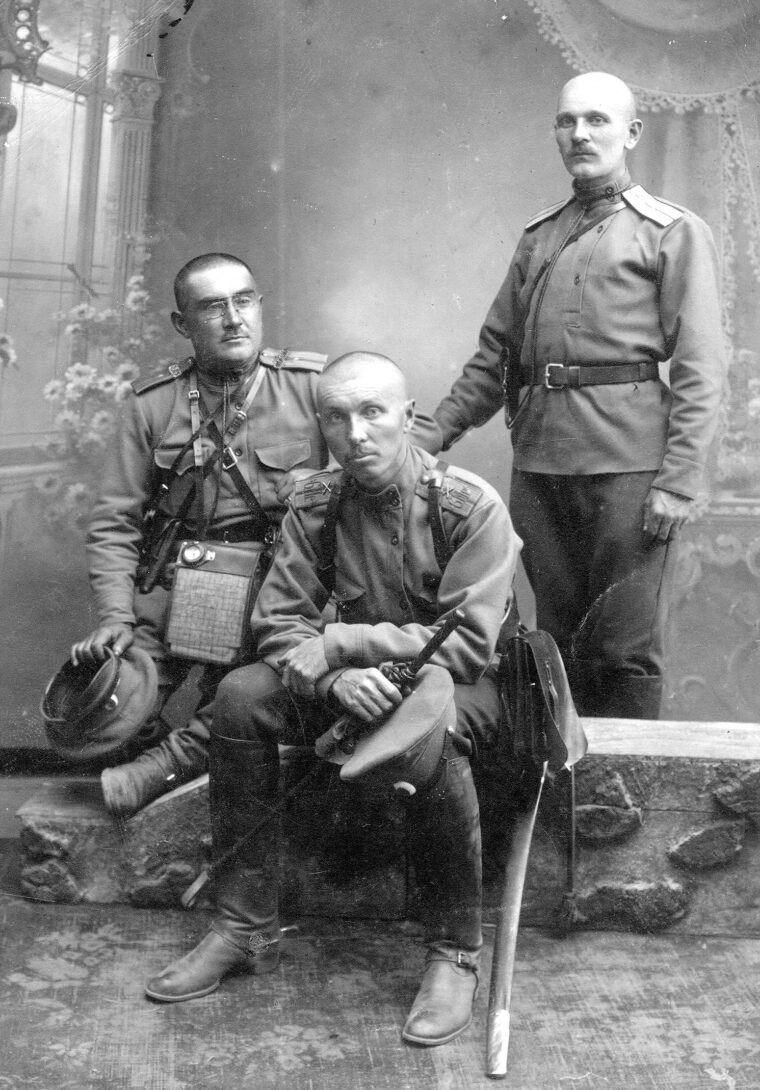

The khaki field uniform worn by the Imperial Russian Army during World War I was created in 1907. Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War a few year earlier led to recognition of the need for field uniforms with some degree of camouflage to replace the uniforms worn up to that time. A service coat, or kitel, with stand collar, five-button front, and two lower pockets, was authorized for wear by enlisted ranks. A similar service coat, with the addition of two breast pockets, was worn by officers.

Branch-of-service piping was added to officer’s tunics on collar and cuffs. The top of the cuff for most officers was straight; cavalrymen had an inverted “v.” The color of these prewar field uniforms, while described in contemporary documents as khaki, was actually a shade of green-gray. Officers’ tunics were tailor-made from good-quality material while that of enlisted ranks was usually of lesser quality, although still superior to the fabric used in Soviet-era uniforms.

In 1912, a field shirt, made in wool for winter and cotton for summer, was authorized for general issue to all ranks. Called the gimnastorka, it was based on the style of the traditional Russian peasant shirt, having a stand collar and a two- or three-button placket in the middle or left side of the chest. It was usually unlined.

Officers’ shirts had two breast pockets with flaps. In 1913, however, breast pockets were also authorized for enlisted ranks, but this style was apparently not universally issued during the war. Buttons could be of metal with the double-headed eagle of the Imperial Russian Army, bone or even wood.

These gimnastorkas appeared in a variety of styles because the standardization found among the millions of uniforms produced by the other combatants, such as Germany and England, was lacking in Russian uniforms of the period. Although the official patterns had been approved, details could vary greatly.

The shirts could have two or three buttons on the placket, and one or two buttons to close the collar. The style of cuff could vary from plain to one having two buttons. Their color could vary considerably as well. The shades of khaki used ranged from brown to light tan, along with green and gray, and the shirts could have patch, or internal pockets, both with flaps. Later in the war, officers began to wear gimnastorkas with four pockets, after the style of their tunics.

Officers’ tunics also appeared with a number of differences in the style of pockets, type of buttons used and so on. The prewar kitel style was made of khaki, with a number of variations in the type of cuffs, pockets and collars.

The most important change during wartime encompassed a style of field tunic known as the “French,” so-named after General French, the Commander of the British Expeditionary Forces in France early in the war. This tunic was an adaptation of the field tunic then worn by British officers in the field. Most had a cotton lining and much larger pockets than the prewar pattern, sometimes with large pleats. Buttons could be standard size, made from bone, wood, leather or the standard brass double-headed eagle. Extra-large plain buttons were also favored with this style. Usually such tunics appeared in the variety of shades also found in gimnastorkas.

One reason for the large variations in uniform details and colors was, no doubt, the confused state of the Russian supply system early in the war. Expecting a conflict to last only a few months at most, planners did not call for large stocks of supplies. Russian industry could not fill the gap quickly; many of the suppliers were small businesses scattered throughout the Russian Empire. The diverse geographic location of these manufacturers, even when used as subcontractors for the major suppliers of military equipment, resulted in less than stringent adherence to official patterns and no doubt helped to create the many variations encountered.

Such vagaries extended to other basic items of uniform, such as the breeches and straight-leg trousers worn by both officers and enlisted men. Those of the former had two stripes of branch piping along the outside seam, while enlisted ranks’ trousers did not. Dark-blue breeches, authorized for peacetime wear, were also used during the war along with the officially authorized khaki of varying shades.

The cap worn with the field uniform was made of wool or cotton and had a crown of medium height and a visor made of leather or composite material, black or khaki in color. A chinstrap of matching color was worn by officers and by some, but not all, enlisted ranks. The fabric used was wool or cotton, matching the uniform. A reinforcing ring was worn inside the crown before the war, but appears to have often been removed in the field. Caps were lined in polished cotton material and the sweatbands of caps were made of leather or a leatherette material.

Completing the uniforms were shoulder straps, a distinctive feature of Russian military wear. Both enlisted ranks and officers wore them to display their rank and unit. Although the system of ranks is too complicated to explain at length, a few basics may be helpful.

Officers straps were made of metallic braid, gold for combatant arms and silver for technical and support troops. Piping of regimental or branch-of-service color was worn around the strap and woven into the braid itself. Company-grade officers added stars for each higher rank, then the stars were eliminated for each successive rank of field grade officer through the rank of colonel. Generals wore straps of solid metallic braid.

Enlisted-men straps were issued in the regimental or branch-of-service color before the war; some were double-sided with the reverse side in khaki. Warrant officers and noncommissioned officers wore strips of braid in different configurations.

The straps of all ranks displayed either the number or cipher of the regiment, battery or unit. These ciphers were often Cyrillic letters representing the first letter of the unit’s name. They were made of metal for officers, and usually painted onto the straps for enlisted men.

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the shoulder straps of both enlisted and officer ranks were only to be made in khaki without any regimental or branch-of-service color, although distinctive unit ciphers and numbers continued to be worn. Unfortunately for the collector, as with other uniform items, there is not one authentic method of manufacture for authentic shoulder straps; a wide variety of original styles can be encountered.

Besides the shoulder straps, another distinctive item of the Russian soldier’s uniform was the footwear worn by all ranks—the ubiquitous black leather boots so often associated with the Russian soldier of the 20th century. Unfortunately for the Russian infantryman, however, the unpreparedness of the Russian army quartermaster at the beginning of World War I again reared its head. Not enough boots were available to issue to the millions of soldiers mobilized in 1914, complementing the shortages of rifles, uniforms and more. It actually became necessary to purchase millions of pairs of boots from the United States to fill shortages.

The importation of war supplies was vital to the Russian war effort, of which boots were a small part. It apparently became necessary to import khaki cloth from Great Britain during the war, because officers’ field uniforms were made of wool gabardine material identical to that used in World War I British officers’ tunics.

The shortage of leather no doubt also affected the issue of the soldiers’ basic field equipment. This equipment, worn by officers and soldiers alike, was similar to that worn by the troops of other armies.

The enlisted ranks wore a basic kit consisting of a brown leather belt, with either a wire or brass plate buckle that held two cartridge pouches for ammunition. A brass mess kit without a top, more like a pot, was worn from the belt along with a haversack, canteen and small shovel held in a brown leather carrier. The overcoat, when not being worn, was rolled and worn over the shoulder. Officers wore a belt with straps over both shoulders, a sword, canteen, map case and pistol, but were usually not burdened with much more.

Field equipment, like uniforms, varied in detail depending upon manufacturer. The differences found in both make it difficult for the collector to determine the authenticity of a prospective purchase, because a single authentic pattern for use as a benchmark does not really exist.

Unfortunately, all this is compounded by copies, some from Soviet film studios, that have appeared on the market. The quality of the wool or cotton used in such copies, however, is generally thinner and less substantial than that found in originals.

The presence of a Russian film studio stamp in the lining, however, does not preclude it from being original, because such studios were one source for original uniforms. As in all aspects of collecting, familiarity with original uniforms and noting details of manufacture can be the best means of determining authenticity.

Imperial Russian uniforms have never been plentiful in the United States, nor even Russia for that matter. Most of the millions of field uniforms manufactured in the decade before 1917 were worn out over the years. In fact the Russian émigré communities that sprang up overseas after the Russian Revolution have often proven to be a better source for such material than Russia itself.

Locating original uniform items can be difficult, but like any collectible they show up in the oddest places. A gimnastorka or cap can sell for well over $350 while an officer’s tunic can fetch over $500.

There are several militaria dealers who endeavor to concentrate their stock to items from World War I, along with antique dealers who specialize in Imperial Russian items; both are more likely than others to offer such items for sale. A few items appear for sale in online auctions, too, usually with illustrations to assist the potential buyer. Regardless of the venue, an opportunity for firsthand examination or a money-back guarantee is preferable when purchasing rarities such as Imperial Russian militaria.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments