By Joshua Shepherd

Benumbed by months of cold and boredom, bleary-eyed British sentries stared over the ramparts of Fort Sackville in the Illinois Country as thick fog rolled in from the Wabash River. But for the barking of a handful of dogs in the adjoining French village of Vincennes, the evening of February 23, 1779, was quiet. The 8th Regiment of Foot had arrived at this backwater post the previous December and, after quickly capturing the American Rebels there, had expected little further action.

So when small knots of men began dashing through the village toward the fort, the sentries stared in disbelief. The running men were definitely not British soldiers, but didn’t appear to be French civilians. Plumes of blue smoke, then the telltale popping of small arms fire, came from the village as lead balls thudded into the fort’s wooden stockade or whined overhead. At an unlikely time, in the most unexpected of locales, the American Revolution had erupted with a savage fury.

The struggle for Fort Sackville was the bitter fruit of bloodshed, vendetta, and outright hatred. The Ohio Valley had for decades been the epicenter of a brutal clash of cultures. Multiple Indian nations, including the Miami, Shawnee, Delaware, and Wyandot united to confront the threat to their traditional homelands during the French and Indian War. From Pennsylvania to Virginia, indigenous war parties wreaked havoc on backcountry European settlers.

Although the end of the war resulted in a brief halt to the bloodshed, a clash over the land was all but inevitable. The 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix only worsened matters. Ostensibly, it secured all the territory south and east of the Ohio River for Great Britain. But the tribal signatories to the treaty, the Iroquois of New York and Pennsylvania, held a dubious claim to the lands in question. Predictably, the natives of the Ohio Valley were outraged by the land deal.

As settlers poured into western Virginia and Kentucky, tensions mounted. By 1774, open warfare erupted with the Shawnee, but the majority of the tribes tried to maintain a fragile peace. Amicable relations were strained to the breaking point the following year, when the Revolutionary War erupted on the eastern seaboard. Tribal militants, sensing an opportunity to push back against the encroaching Americans, continually harassed the vulnerable farms and outposts of the sparsely settled frontier.

Matters were only exacerbated by a British presence in the Great Lakes. Foremost among the western posts was the grand entrepot of Detroit, which dominated the region’s vital fur trade. For the tribes of the Ohio River basin, the trade goods available at Detroit had become a necessity of life. As the Revolutionary War intensified, the tribes increasingly gravitated into the British orbit. British officers continued to publicly advocate for tribal neutrality, but it became increasingly apparent that Indian participation in the war was all but inevitable.

By 1777, the British ministry reversed course and made a decision of epic magnitude. In official orders released that March, American Secretary Lord George Germain informed commanders in Canada and the Great Lakes that “It is His Majesty’s resolution that the most vigorous Effort should be made, and every means employed…for crushing the rebellion.” In simple terms, the gloves had come off; the Crown ordered officers on the ground in the American backcountry to openly court the help of Native American allies in “exciting an alarm” on the American frontier.

It was a decision that would have horrific consequences to both American settlements and Native villages across the frontier. As the British army began to provide south-bound war parties with ample supplies of arms and ammunition, attacks on American homesteads increased at an alarming rate, leaving a terrifying trail of blood across the frontier. Kentucky, which at that time possessed a mere handful of defensible stockades, suffered egregiously. The first year of sustained Indian war would forever be remembered as the year of the “Bloody Sevens.”

Although volunteer militias fought hard to stem the tide of enemy incursions, raiding parties operated with near impunity: killing isolated pioneer families, cutting off communications between settlements, and keeping homesteaders from working their fields. Little distinction was made between civilians or combatants, male or female. In the hinterlands of the far west, the Revolutionary War was a brutal and personal affair that degenerated to a horrific contest of revenge and reprisal.

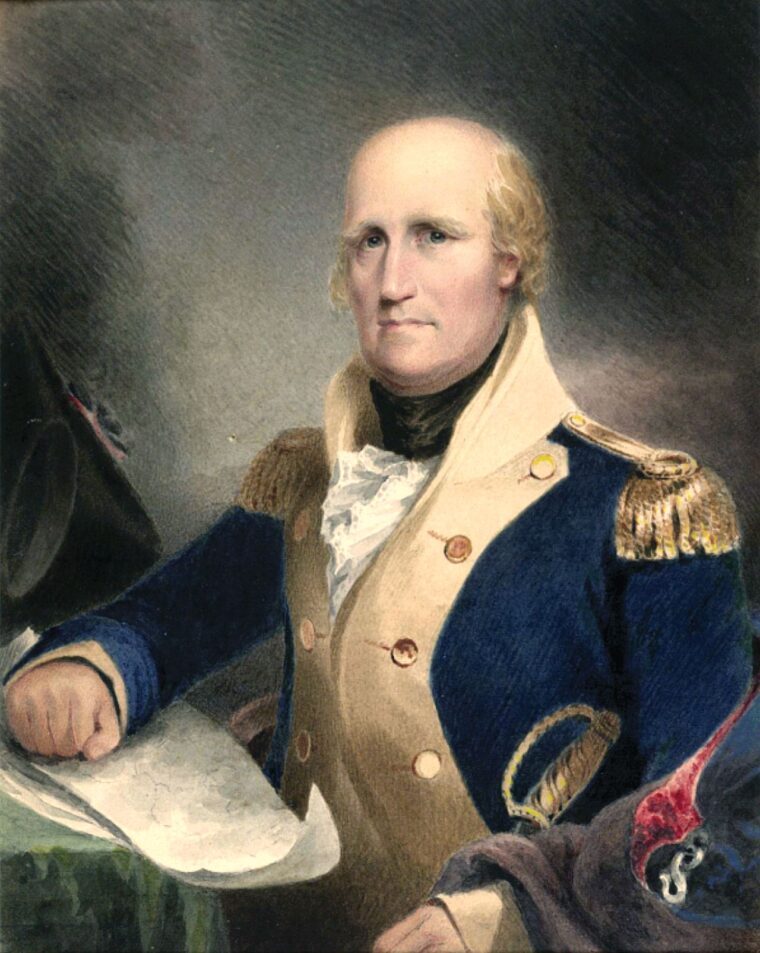

But during the worst year of the fighting, a natural-born leader rose to prominence. At 25, George Rogers Clark was an obscure militia officer whose star was on the rise. A native Virginian, Clark had sought his fortunes in the west. Initially working as a surveyor, Clark cut his teeth in the military during the Indian conflict of 1774. Possessing a keen intellect, a forceful personality, and persuasive manners, Clark was quickly regarded as one of Kentucky’s foremost leaders.

In 1776, the settlers elected Clark to present their interests to the government of Virginia in Williamsburg. Clark was instrumental in securing Virginia’s recognition of Kentucky, and the Old Dominion agreed to absorb the Kentucky settlements into the state, creating three counties. Just as importantly, Virginia provided Clark with vital supplies—500 pounds of gunpowder—for the defense of the Kentucky settlements.

As British-allied natives ravaged American settlements south of the Ohio River, it became apparent to Clark that waging a reactionary defensive war against swift-moving Indian war parties would prove futile. By nature a reclusive thinker, Clark began contemplating a way to seize the strategic initiative and take the war to the enemy. He would prove to be the ideal man for the job.

Clark intuitively grasped that the Indian threat to Kentucky could never be stopped unless their ties to Britain, and access to vital war materiel, were cut off. Although Detroit was the logical prime target for the Americans, seizing subordinate British installations farther south would be an obvious first step.

Foremost among them were two posts in what was then known as the Illinois Country: Kaskaskia, near the Mississippi River and Vincennes, on the lower reaches of the Wabash River. The British forts at both locales regularly supplied south-bound Indian raiding parties. Hoping to gather firmer intelligence, Clark dispatched two men, Benjamin Linn and Samuel Moore, to Kaskaskia.

Posing as roustabout frontiersmen, the duo explored Kaskaskia undetected and gained a first hand view of enemy defenses. The information they reported to Clark was irresistible. The town’s defenses were in shambles. Although a British governor was present, he had no British troops under his command, and the town was defended by local French militia whose loyalties to Britain were decidedly lukewarm.

Armed with the information, Clark traveled to Williamsburg late in 1777 and sought authorization for an ambitious campaign to attack the British posts in the Illinois Country. Clark offered Virginia authorities control of a vital, if remote, region which commanded the trade routes linking the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley. British neglect left the area virtually undefended, inviting attack. Capturing the posts in Illinois would interrupt the enemy’s fur trade, discourage the region’s tribes from British alliance, and secure American communication with Spanish Louisiana.

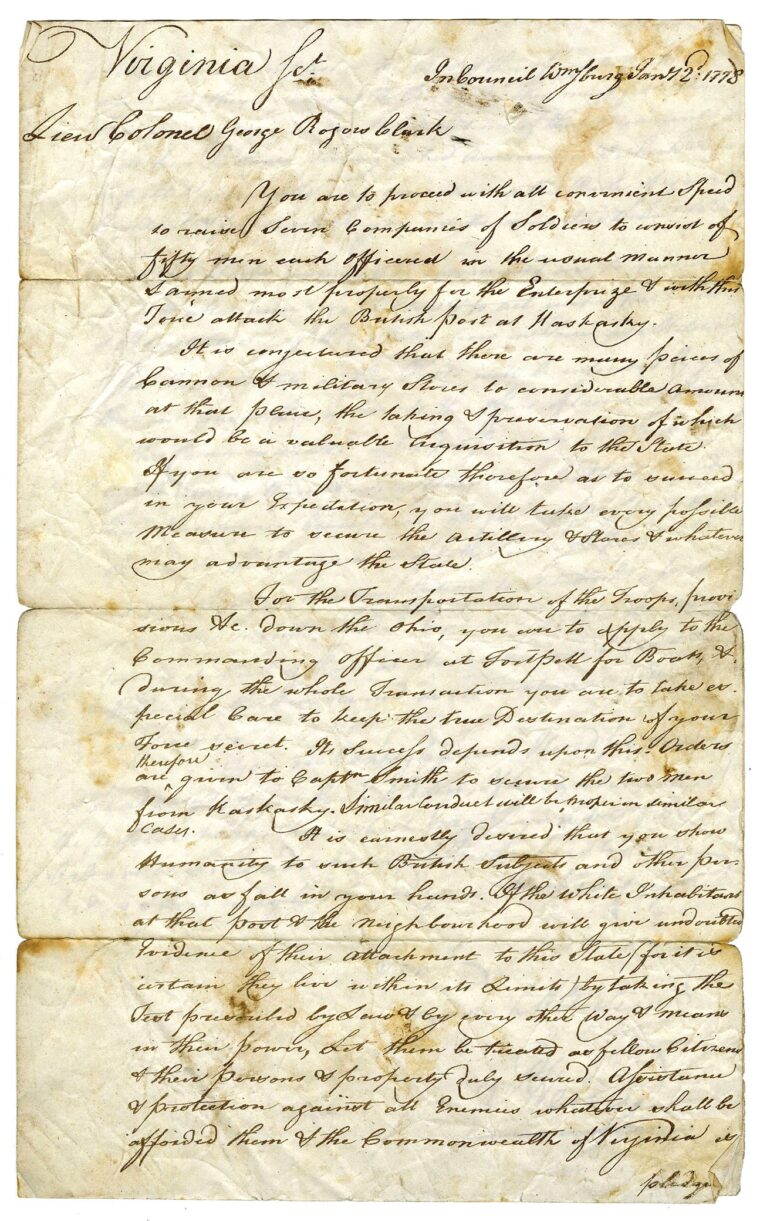

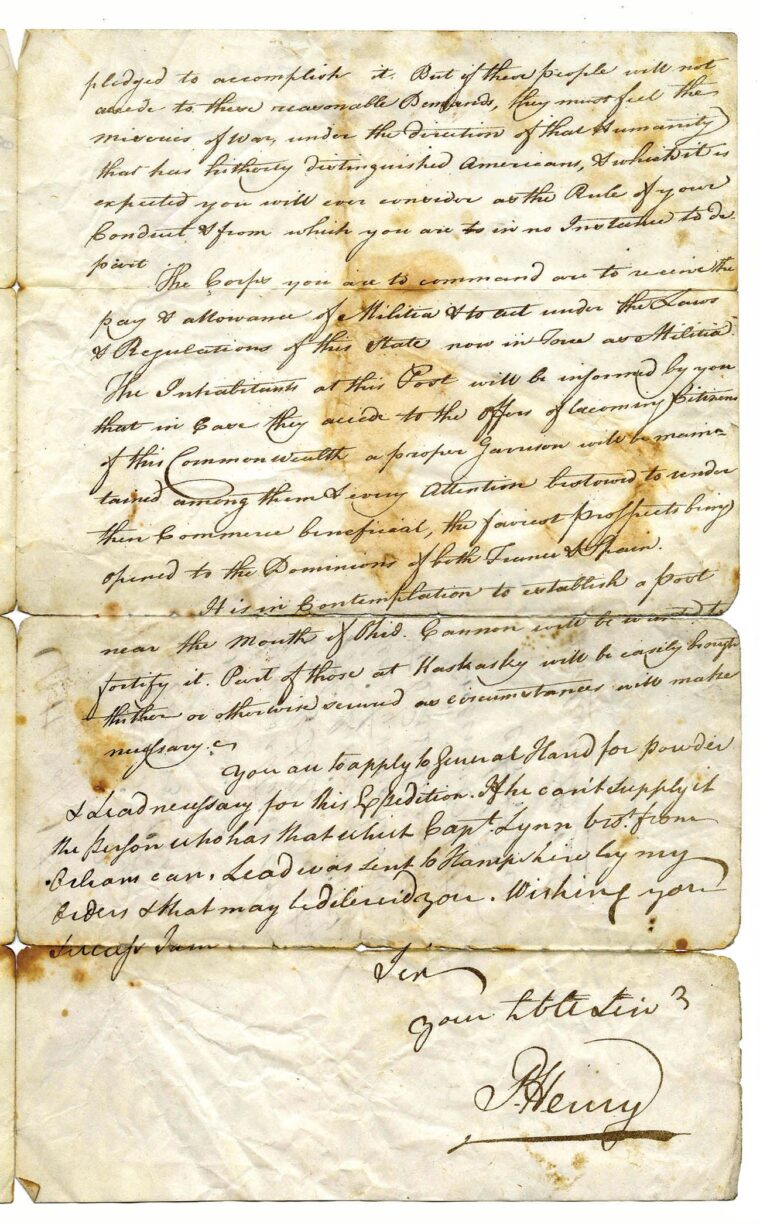

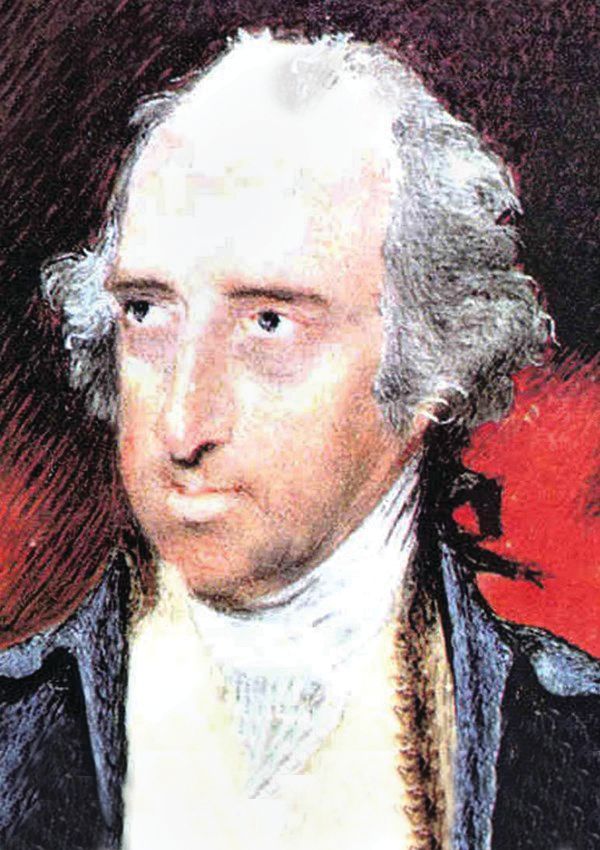

Governor Patrick Henry was enthusiastic about the bold plan, but, fearful of losing the element of surprise, was hesitant to publicly seek legislative approval. Ultimately, Clark was given sealed orders for the expedition, and authorized to target Kaskaskia.

From the outset, Clark’s campaign was to be a grim exhibition of vengeance. Clark’s orders asserted that the western Indian nations had “without any provocation, massacred many of the Inhabitants upon the Frontiers of this Commonwealth, in the most cruel and barbarous Manner.” The campaign into Illinois was intended “to revenge the Injury and punish the Aggressors by carrying the War into their own Country.”

Dispensing retribution would prove to be a game at which Clark excelled. To carry out his orders, Clark set about recruiting the best that the frontier had to offer, a tough lot of men accustomed to the rigors of the wilderness. Clark’s ranks would be filled with professional hunters, frontiersmen, and a good number of men who had seen action against the Indians. Largely recruited from across the Virginia backcountry, the men were to rendezvous at the Falls of Ohio River over the summer of 1778 before setting out for Kaskaskia.

Although recruiting proved painfully slow, Clark’s force began gathering in the spring at the Falls of the Ohio (site of modern Louisville, Kentucky). Clark would eventually have an all-volunteer force of 175 men who knew the potential dangers of a wilderness campaign, but were eager to run the risks. While he gathered supplies and made final preparations for a push into the Illinois Country, Clark organized his troops into four companies under the command of trusted subordinates Captains Joseph Bowman, Leonard Helm, James Harrod, and John Montgomery.

On June 24, Clark had his troops in motion. After receiving a fortifying ration of whiskey, the men manned a small fleet of batteaux (flat-bottomed wooden boats traditionally pointed at both ends) and headed downstream on the Ohio River, hoping to quickly close the distance to the Illinois settlements. At the mouth of the Tennessee River, his scouts stumbled across a party of American hunters who had recently visited Kaskaskia. The men informed Clark that the town’s French militia were decidedly unenthusiastic subjects of the British monarch, and due to wild frontier rumors, the locals were terrified of the Virginians and regarded them as little more than barbarians.

It was a welcome bit of intelligence that Clark would capitalize on. When he reached the ruins of the old French Fort Massac, Clark hid his boats and headed overland on a grueling 120-mile march across the wilderness. On the final two days of the approach, the men pushed hard and went without rations. As the sun began to set on July 4, Clark’s men were within sight of Kaskaskia.

Fortunately for Clark, he had succeeded in approaching the town completely unnoticed. Commandeering a handful of boats, the men crossed the Kaskaskia River under cover of darkness and spread out across the town. Clark led a party that secured the British fort, which was largely unmanned. Breaking into the commander’s quarters, the Virginians captured the startled Governor Phillippe Rocheblave in his nightclothes.

For Clark, the capture of Kaskaskia had been a bloodless coup. He moved quickly to consolidate his hold on the region, dispatching Captain Bowman with 30 mounted men to seize the nearby towns of Cahokia, St. Philippe, and Prairie du Rocher. The local French population quickly realized the Virginians were, in fact, not barbarians. They proved decidedly friendly to the American cause, particularly when Clark informed them of the recent alliance between the United States and the Bourbon monarchy.

Clark also proved himself to be skilled at the subtle art of diplomacy. Calling together an Indian council, he defiantly offered the tribes either the white belt of peace or the red belt of war. Although in no position to confront the tribes, Clark’s bluff worked. Admiring his bold posturing and recent capture of Britain’s possessions on the Mississippi, the tribes of the Illinois Country agreed to a tenuous peace.

Despite his fierce demeanor, Clark was decidedly gracious to the French settlers of Illinois, and the approach paid off. The most influential Frenchman in the area, Father Pierre Gibault, enthusiastically cast his lot with the Americans and encouraged his parishioners to do the same. Gibault proved his loyalties by traveling across southern Illinois to the French town of Vincennes on the Wabash River where, remarkably, he convinced the town’s inhabitants to switch their allegiance to the Americans.

Adjacent to the village, Fort Sackville was now ripe for the taking. Clark ordered Captain Helm to Vincennes, where he assumed command of the French militia on the Wabash River. In little more than two months, Clark had accomplished the unthinkable, capturing every British-held town in the Illinois Country and securing the good favor of the region’s inhabitants.

The British were far from idle when the news of Clark’s exploits reached them. Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton in Detroit learned of the fall of the Illinois Country late in the summer of 1778. On a violent frontier where hate and retribution could all too often be a way of life, Kentuckians reviled Hamilton the most of all Britons. A cultured English gentleman who had initially scorned the use of Indian allies, Hamilton eventually found himself walking an uncomfortable tightrope by following a decades-old diplomatic tradition of providing victorious Indian allies with supplies and ammunition. While there isn’t any direct evidence, many believed that Hamilton’s “gifts” were in exchange for American scalps, earning him the unflattering sobriquet “Hair Buyer” from outraged settlers.

When informed of the British disaster in the Illinois Country, Hamilton immediately took steps to strike back before the American rebels could strengthen their gains. “It appeared to me expedient,” he later explained, “to attack them as soon as possible, & before they should be reinforced, or have time to engage the Indians in their interest.”

The governor assembled some 160 men composed primarily of Detroit militia, but including a solid core of 33 men from the 8th Regiment of Foot. The force was augmented by Indian auxiliaries, who were accompanied by 14 officers from the Indian Department. Hamilton’s force was well armed and well supplied from Crown stores in Detroit, and would enjoy a relatively easy, all-water approach to Vincennes.

In a small fleet of batteaux, Hamilton led his army onto Lake Erie, then up the Maumee River. After a short portage at the site of modern Fort Wayne, Indiana, Hamilton’s force gained direct access to the Wabash River, which would lead them directly to Vincennes. The 600-mile journey took more than two months.

Because the route went through the heart of major Indian settlements, Hamilton took his time, stopping in all the larger Indian villages he passed. A shrewd diplomat, Hamilton strengthened his alliances with the tribes with continued gifts, and his ranks eventually swelled as 350 warriors joined his army.

When Hamilton’s force finally reached Vincennes on December 17, it became readily apparent that they wouldn’t have to fight for Fort Sackville. Captain Helm commanded a fort in a miserable state of disrepair, manned by a force of just 25 French militia, who promptly deserted. While the British forces spread out and surrounded the fort, Hamilton sent a demand for surrender. Admirably defiant in the face of such overwhelming odds, Helm refused to surrender immediately, and asked for terms.

Hamilton graciously humored the young captain, allowing him to haul down his colors before surrendering. After occupying the fort, Hamilton was forced to make a decision with far-reaching consequences. Rather than press his campaign toward Kaskaskia so late in the season, the governor opted to remain in Vincennes for the winter, gather fresh forces in the spring, and deal with Clark’s main force in Illinois when the weather broke.

Not wanting to unnecessarily maintain such a large force over the winter, Hamilton also dismissed his Indian allies and the bulk of the Detroit militia. He then set about repairing the decrepit stockade of Fort Sackville. It was an imposing task, but with little else to do over the cold winter months, his work details made some progress.

In Kaskaskia, Clark received news of the disaster on January 29 when Francis Vigo, a St. Louis trader sympathetic to the Americans, arrived in town. Vigo not only reported the fall of Vincennes, but gave Clark the best information he had on the size of the remaining British force. For the small American army in Illinois, the loss of Vincennes was simply staggering. With the British in full control of the lower Wabash River, Clark’s primary line of communication to the east —the Ohio River—was badly compromised.

Clark was in a perilous situation. He clearly couldn’t entertain the notion of abandoning his gains in Illinois, but if he simply waited until the spring it was obvious that Hamilton would reconstitute overwhelming force and crush the Americans along the Mississippi. True to character, Clark quickly decided to seize the strategic initiative and launch his own preemptive attack against Hamilton in Vincennes.

In a hasty letter to Virginia authorities, Clark reported his decision to gamble everything on a daring midwinter campaign. It was a decidedly risky decision, but Clark felt it imperative to strike Hamilton before his forces could consolidate in the spring. The situation was desperate, he informed Henry, but the Americans had only two choices: “quit the country or attack Mr. Hamilton.”

Waiting for events to unfold was unthinkable for the audaciously aggressive young Virginian, whose boundless optimism proved contagious. His bold plan to attack Fort Sackville in the dead of winter was so unorthodox that it captured the imagination of the local French, who began to volunteer for the campaign in good numbers. Clark enlisted two additional companies of French militia to augment his own core force of Virginians. All told, Clark would lead a small but dedicated army of 172 men.

Hoping to move fast and free his men from the burden of excess baggage, Clark dispatched the armed supply boat Willing up the Ohio River. Its commander, Lt. John Rogers, was to guard the mouth of the Wabash River from enemy traffic and then join up with the main body near Vincennes.

On February 6, 1779, Clark and his men began a nearly 200-mile trek across what is now the state of Illinois, heading east towards difficulties that none could have foreseen. Heavy winter rains had pushed creeks and rivers far beyond their usual banks, covering open grasslands with several inches of water. Bottom ground was sometimes flooded to a depth of two to four feet. Clark, never one to be easily discouraged, wrote that the campaign degenerated to “a difficult and very fatiguing march.”

That was a colossal understatement for his exhausted men, who struggled to make progress across miles of miry ground. Staying dry was nearly impossible for the footsore soldiers. Occasionally the little army would stop on high ground, make fires to cook provisions and dry out moccasins—before once again slogging across the flooded winter landscape. With few provisions, they largely subsisted off the land. Small hunting parties flanked the main body, scouring the countryside for deer, but the men grew famished as they expended far more calories than could be replaced.

Despite the hardships, morale remained surprisingly high. Exhibiting the best characteristics of a combat commander, the irrepressibly confident Clark led by personal example and offered constant encouragement for his beleaguered men. As they prepared for the final push to Vincennes on the morning of February 22, they faced a vast chest-deep floodplain. Undaunted, Clark grimly blacked his face with gunpowder and was the first into the water.

As Clark’s half-frozen scarecrows trudged the last few grueling miles to their objective, it was clear that the troops were eager to get at the enemy. The men, Capt. Joseph Bowman recorded in his journal, were gripped with thoughts of “revenging the wrongs done to their back settlements.”

On the afternoon of February 23, Clark’s army was in sight of Vincennes. As he scanned the fort, Clark realized that he had achieved complete surprise, and immediately ordered his troops to unfurl their flags and march toward the village. As he neared the town, he ordered the troops to march repeatedly behind a small hillock—the simple ruse giving the impression his army was much larger than it actually was.

The men fanned out to secure Vincennes, and, using homes and outbuildings as cover, worked their way close to the stockade walls of Fort Sackville. When they were in position, they opened fire on the fort. The bulk of Clark’s Virginia troops were armed with rifles, and they opened up a galling fire on the fort’s defenders. Although the British had begun repairs to the stockade, they hadn’t finished the work, and paid smartly for it.

Inside the fort, Hamilton and his men were in a state of disbelief that an American army had virtually appeared out of thin air. The startled governor later explained that a man could shove his fist between many of the logs in the palisade, which proved a decided disadvantage to his men. While his troops fired smoothbore muskets at well-concealed Americans, Clark’s men unleashed a gallingly accurate fire at the British troops. Hamilton also opened fire with the fort’s artillery, which produced a thunderous racket but made little effect on the Virginians.

During the first night’s fighting, four of Hamilton’s wounded were carried to the officer’s quarters in Fort Sackville. Clark’s men made it through the battle without a scratch. The decidedly one-sided fight was, crowed Captain Bowman, “fine Sport for the sons of Liberty.”

When fighting resumed at first light, the situation only worsened for Hamilton. Some of Clark’s riflemen had worked to within 30 yards of the log walls, and maintained such an accurate fusilade that British troops were hesitant to even show themselves long enough to return fire. Three more Crown troops were wounded, and Hamilton’s remaining French militia exhibited no taste for fighting. Amid an incessant whine of rifle fire, there was little that the fort’s garrison could do.

At about 8 o’clock in the morning, Clark was confident enough to send a demand for surrender under a flag of truce. It was less than a cordial summons. Clark made no attempts to hide his disdain for Hamilton the “Hair Buyer” and demanded that he surrender his garrison as prisoners at discretion—with no honorable terms. The young colonel likewise warned that if Hamilton destroyed any papers or public stores “you may expect no mercy, for by Heavens you shall be treated as a murderer.”

Hamilton, naturally, rejected such terms, and then paraded his garrison to announce his decision to resist the Rebels “to the last extremity.” Hamilton’s British troops were inspired by his stubborn rejection of the Rebel ultimatum and were eager for more fighting. The Redcoats spontaneously cried out “God save the King!” and then unleashed three cheers. Unfortunately for Hamilton, his sheepish French militia hung their heads and confessed their unwillingness to continue the fight against their own relations in Vincennes, who were clearly aiding the Americans.

Hamilton was thunderstruck. Realizing that he only had about two dozen able-bodied men that he could rely on, the governor immediately came to the conclusion that he would surrender if given honorable terms. He met privately with his officers to reveal his intentions, but found them hesitant to give in so fast.

Hamilton’s behavior was certainly a deflating display of indecision. Only moments before he had argued for a fight to the death, but now just as forcefully pleaded for capitulation.

Hamilton’s observations were gloomy indeed: the French militia were treacherous cowards, he insisted; seven of the English troops were already wounded, and Fort Sackville was 600 miles removed from any possible reinforcement. Grudgingly, his officers agreed.

Fighting resumed for another two hours, and then Hamilton made a play for time. He sent out the captive Captain Helm with terms; Hamilton suggested a three-day truce, as well as a face-to-face conference within the walls of Fort Sackville. Clark refused, demanding nothing short of surrender at discretion, but he did make arrangements to meet Hamilton in front of the village church.

When it appeared that further pointless fighting would ensue, Hamilton experienced a setback at the worst possible time. During the lull in the fighting, a party of about 15 Indian warriors returned to the fort after a victorious raid into Kentucky. Since they heard no gunfire and could see the British flag still flying above the fort, the warriors confidently approached the village and fired their weapons in salute.

Clark sent out a party of troops to meet them; the Indians, assuming that they were being welcomed to town by French militia, had no idea what awaited them. From near point-blank range, the approaching Virginians unleashed a volley into the warriors; several were killed outright, a few more staggered off into the nearby forest. Seven of the warriors were captured and escorted into Vincennes.

After viewing the Indians fresh off a raid into Kentucky, Clark was in no mood to show mercy. He was prevailed upon to spare the life of an18-year-old brave, as well as two French partisans who had friends in Vincennes. The remaining Indians were condemned to a brutal exhibition of summary frontier justice.

The Indians were led to a street directly in front of the fort and forced to kneel. Realizing their fate, the warrior began to sing a death song. With little ceremony and in full view of the British garrison, the four Indians were coolly tomahawked in succession. In a harsh ending to the gruesome spectacle, the corpses were bound about the neck with rope, dragged through the mud toward the Wabash, and thrown into the river.

The brutal affair had rattled both Hamilton and his men, and clearly played on British fears that the frontier Virginians were little better than savages themselves. Just moments after the execution of the Indians, Clark arrived at the village church for his meeting with Hamilton. The young colonel, who was covered in blood, made a shrewd play at psychological warfare. Instead of immediately opening negotiations, Clark sat on the edge of a boat and proceeded to make use of a puddle to wash the blood from his hands and face.

Clark’s dark ploy clearly cowed Hamilton. Aware that he had the upper hand, the young Virginian behaved rudely toward Hamilton and warned the governor not to try bargaining for better terms. He also said he would soon have artillery brought up, and if he were forced to storm the fort, he would show no quarter. To drive home the point, Clark told Hamilton that he knew the French militia in the fort wouldn’t fight.

Hamilton was at pains to counter the arguments, and the two men agreed to meet again in 30 minutes. Clark remained defiant, but Hamilton was equally stubborn. After another round of useless arguing, Hamilton had had enough, and declared that he would fight it out; after shaking Clark’s hand, the governor began stalking back into Fort Sackville.

Junior officers from both sides were aghast. Captain Bowman, joined by the Loyalist Maj. Jehu Hay, pleaded with Hamilton to return to the negotiations and avoid further useless bloodshed. Clark and Hamilton finally came to terms; the governor was afforded the barest of concessions. The British officers would be permitted to keep their personal baggage, while the garrison would be allowed to march out of their fort with arms and accoutrements.

The following morning, Hamilton led his troops out of the fort. All told, the Americans had 79 prisoners, so many that Clark and his men were “uneasy” guarding so many men. Hamilton confessed mortification over the entire affair. He was left in particular consternation over the appearance of the unkempt and unshaven Virginians. His entire garrison, Hamilton bemoaned, had been captured by “an unprincipled motley banditti.”

The governor and his men would face a humiliating imprisonment in Virginia, while Clark and his men strengthened their hold on the Illinois Country. The direct influence of British presence had been rolled back to Detroit and the Great Lakes. With Vincennes and Kaskaskia firmly in American hands, the tribes of the Illinois Country and lower Wabash Valley were drawn increasingly under American influence.

The strategic consequences of Clark’s campaign were mixed. One of the primary goals of the expedition, eliminating the Indian threat to Kentucky, had only partly succeeded. Although the tribes around Kaskaskia and Vincennes would remain neutral for the duration of the war, more intransigent tribes farther to the north, who had ready access to British supplies, would remain inveterate enemies of the Americans. The bloody frontier war in the American west would continue unabated.

Clark would face the thorny dilemmas of theater commanders throughout history—dismissive politicians and uncooperative bureaucracies. Although Clark continued to plead for greater material aid for the war in the west, his dream of ending the conflict by seizing Detroit once and for all would never materialize. An increasingly cash-strapped Continental Congress, preoccupied with seemingly greater threats on the eastern seaboard, turned a deaf ear to the needs of the sparsely populated western settlements. Due to unfortunate governmental inaction, Clark’s stunning victory would never be fully exploited

Despite his frustrations, Clark’s legendary campaign to seize Fort Sackville remains one of the most audacious and daring operations in American military history. Against all odds and in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles of terrain and logistics, Clark and his men relentlessly pursued victory. By sheer force of will, Clark combined sound strategic thinking and inspiring leadership to accomplish the impossible.

He had voiced that boundless optimism at the outset of the campaign. “Who knows what fortune will do for us,” he had written, “Great things have been effected by a few Men well Conducted.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments