By Christopher Miskimon

As summer neared its end in early September 1944, the U.S. Army raced across northern France toward the German border. For over a month after the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, American armies chased their disorganized and exhausted German foes inexorably across territory held by the Third Reich since 1940.

General George Patton’s Third Army acted as a spearpoint aimed at the Nazi heartland, smashing every hastily built defensive line the Germans had created as they retreated headlong toward the Rhine River. Hope of a quick victory began to build; many Joes and Tommys thought the war would be over in just a few months, spurring rumors the troops would be home by Christmas.

After the past four years of endless, numbing combat, it all seemed too good to be true; and it was. The Allied advance did proceed at a remarkable pace—until the leading divisions began to outpace their supplies.

By September, Patton and other senior commanders received warnings that their fuel rations were about to be cut dramatically. Third Army alone needed 400,000 gallons of gasoline a day to continue operating at full pace. There simply were not enough trucks and operable trains to provide the fuel, ammunition and supplies that the highly mechanized Allied armies’ columns needed to maintain the advance. For an aggressive, offensive-minded leader like Patton, this was bitter news. He knew that if the Germans had even a brief period to reorganize, they could put a stop to further Allied gains. But he had little choice; he slowed his advance while the supply lines caught up to meet the needs of the frontline units.

Third Army slowed its pace in Lorraine, a province in northern France near the German border. Defending this area was the German 1. Armee — so weak and disorganized a force that its defensive actions proved less a hindrance to the Americans than did the Yanks’ own fuel shortages. The German high command believed U.S. Third Army would soon mount a major offensive toward the Rhine River in that area.

As Patton’s army waited for its gasoline supplies to arrive during the first week of September, the delay only reinforced Pattens discomfort.

German intelligence, however, failed to realize the Allied fuel situation and believed that Patton’s pause signified that he was preparing for an attack toward the Rhine. 1.Armee’s commander, General Kurt von der Chevallerie, conceived a spoiling attack to frustrate Patton’s nonexistent Rhine-crossing attack.

In simplest terms, a spoiling attack is one made to disrupt an impending enemy attack, preventing it from occurring. But Kurt’s ineffectual efforts merely provided the Germans additional time to reorganize and reinforce.

The Germans had already gathered a force of their own for a counterattack against Patton, carefully husbanding it so it would be large enough to achieve a decisive result. Panzer and panzergrenadier (motorized infantry) divisions composed most of the attack force. All of them had seen recent heavy combat, and a few were still actively engaged on other parts of the front. These divisions lacked the tanks, half-tracks, and personnel to be at full strength, though they did have a core of experienced troops on-hand.

The remaining units in this force comprise six newly formed panzer brigades, a new sort of unit partly based on the kampfgruppen (ad-hoc, combined-arms formations) used on the Eastern Front to respond to enemy breakthroughs and stabilize areas of the front. Due to the desperate situation, General Chevallerie received permission to use Panzer Brigade 106 for his spoiling attack south of Metz. Any use of the brigade had to be personally approved by Hitler, however. The unit would return to its original mission afterward, later taking part in the counterattack called by the Germans the Vosges Panzer Offensive.

Panzer Brigade 106 was a compact yet powerful unit. Its main strength consisted of a panzer battalion with three companies of Panther tanks and one company of Panzer IV/70 tank destroyers, which mounted the same powerful 75 mm high-velocity cannon as the Panther in a turretless chassis. Alongside the tanks was a panzergrenadier battalion of five companies, though Panzer Brigade 106 eventually boasted eight companies. Each company had halftracks to carry the infantry; six halftracks in each company also sported triple 20 mm automatic cannon, useful against aircraft and ground targets. Some carried 75 mm howitzers for infantry fire support. At full strength, Panzer Brigade 106 numbered 2,100 troops and included support units such as engineer and reconnaissance companies. The brigade bore the moniker Feldherrnhalle (“Field Marshal’s Hall”), since it was built around 347 survivors of a panzergrenadier division of the same name, destroyed on the Eastern Front in July 1944.

Colonel Franz Bäke commanded the brigade. An experienced tank officer, while serving on the Eastern Front he had led the Heavy Panzer Regiment Bäke, a “fire brigade” unit equipped with Tiger and Panther tanks. Panzer Brigade 106 was also partly based on this special unit. Bäke held the Knight’s Cross, a high decoration for valor in the Wehrmacht.

Despite its heavy direct-action firepower, the brigade had several weaknesses. It had no integral artillery to support it, leaving it dependent on supporting division or corps assets to provide fire support. American armored units of similar size, called “Combat Commands” in U.S. armored divisions, generally had at least one battalion of self-propelled artillery assigned, giving them the ability to quickly place fire on enemy units. Panzer brigades lacked the ability to do so. These new German units were also composed mainly of new recruits with little time for complete training. The pressure to get them quickly committed to combat meant most of them did not get their into their tanks until a week or two before going into action. This left no time for proper training.

Likewise, the various components of each brigade were raised in different areas and did not meet until they arrived together for deployment. This left no time to develop the cohesion and combined-arms proficiency necessary for combat effectiveness. Despite these problems, Germany needed these brigades to enter the fighting; there was no one else available.

Berlin approved Chevallerie’s plan on September 5, 1944, admonishing him that the brigade would return to centralized control in two days. Some elements of 19. Volksgrenadier-Division and 15. Panzergrenadier-Division reinforced the brigade. Their official orders were to attack from the area of Longwy-Aumetz in the Etain area southeast of Metz, clarify American dispositions, and destroy whatever enemy forces were found there. The attack would begin on September 7.

The American 90th Infantry Division of the XX Corps stood in the path of the German attack. The division carried the nickname “Tough ‘Ombres” based on their shoulder patch, which bore the letters T and O, due to the unit’s original recruitment areas in Texas and Oklahoma. As with most infantry divisions, the need to replace casualties meant the unit included soldiers from across the United States.

The 90th had landed on Utah Beach at Normandy after the first waves on D-day. Its initial combat service was poor, and the division was almost disbanded; but leadership changes resulted in General Raymond McLain assuming command by August 1944. His efforts improved the division dramatically, so that by early September it was a veteran unit with replacements for the heavy casualties it had previously taken.

The 90th ID also had several important attachments to augment its combat power. The 712th Tank Battalion joined the division at the end of June; by September, it was fully incorporated into unit operations. Four tank companies made up the 712th: three employed the M4 Sherman medium tank, while the fourth used the light M5A1 Stuart. The Stuart was useless in a tank-to-tank confrontation but was highly effective in reconnaissance, screening, and support roles.

Tanks were usually allotted out to the division’s infantry regiments at a ratio of one tank company per regiment. To assist against German armor, XX Corps also attached the 607th Tank Destroyer Battalion to the 90th. Its three companies each fielded a dozen M5 76 mm towed anti-tank guns, also usually split among the division’s regiments.

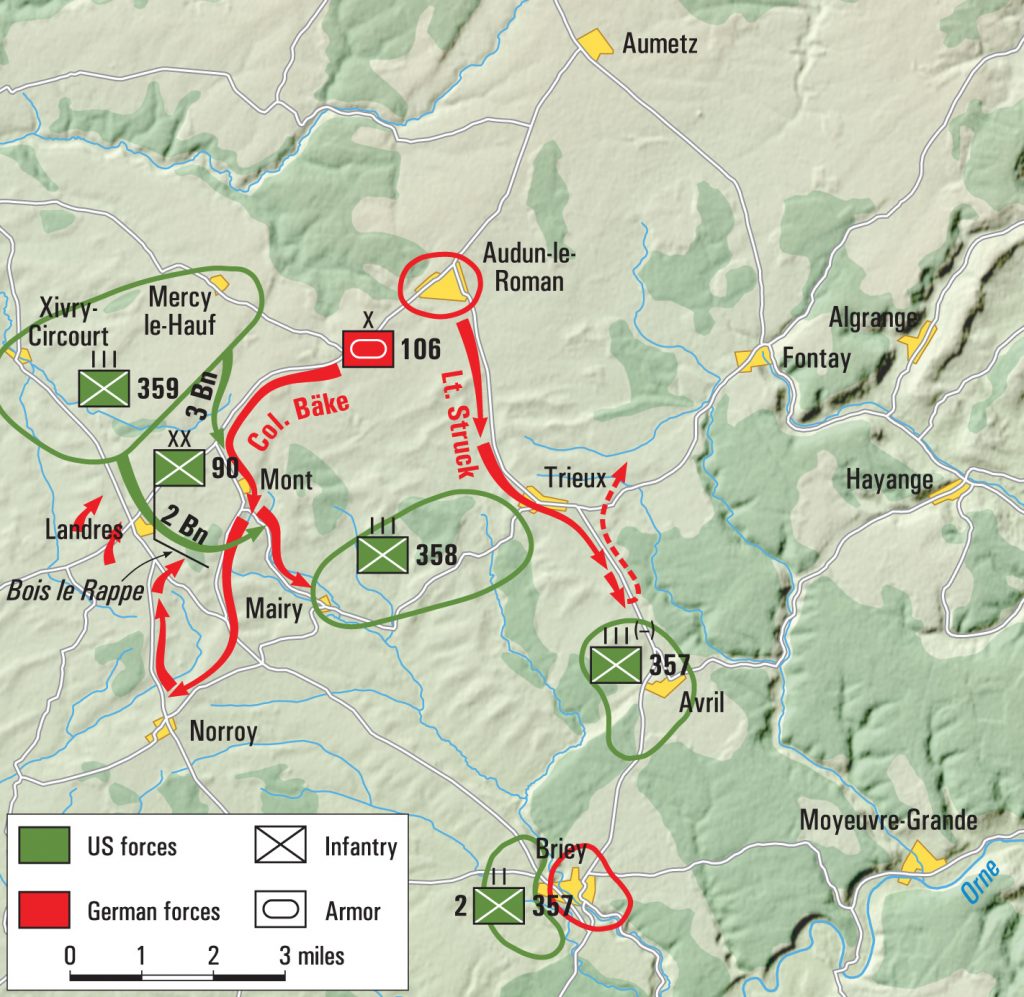

The German attack immediately got off to a sputtering start. Scheduled to begin at 11:00 pm on the night of 6-7 September, Panzer Brigade 106 arrived in their forward assembly area at 8:00 pm, only to discover that the infantry of Grenadier Regiment 59 / 19th Grenadier-Division had not deployed. When the brigade contacted the division, they discovered that higher command had never informed the Grenadier division of their orders. Almost six hours passed while the Grenadiers received their new orders and arrived in place at just before 2:00 am on September 7. Colonel Bäke split his now reinforced kampfgruppe into two stossgruppe (“Shock Groups”), each a mix of tanks and infantry with engineers in support. A small number of infantry, tanks, tank destroyers and anti-aircraft vehicles formed a reserve, and a detachment was assigned to guard the brigade headquarters in the village of Audun-le-Roman.

The leading German troops reached the village of Briey an hour later but found no American troops. Several reconnaissance patrols swept the area to the southwest and west but found nothing. A planned rendezvous with 15. Panzergrenadier-Division in the nearby village of Landres did not materialize either, and further patrols failed to locate these missing friendly forces. The night’s action accomplished nothing except the destruction of a bridge southeast of Briey. As a new day dawned over the French countryside, Bäke ordered his troops to return to their staging areas near Audun-le-Roman.

Unknown to the Germans, fuel shortages had also caused the failure of the Americans to find their own enemy. The 90th Division had to delay its planned attack until September 7th while sufficient gasoline arrived. The German plan simply miscalculated where the Americans would be by the time Bäke’s advance began. When the American assault did begin, it quickly pushed back the two German units defending the area, 559. Volksgrenadier-Division and 19. Grenadier-Division. The situation became so dire that 1. Armee issued Bäke new orders in the early evening of September 7 to make another attack toward Briey. Gen. Chevallerie hoped to restore the defense line with this move before the panzer brigade reverted to its original mission.

The renewed attack started as soon as the brigade could get ready. Around 8 to 10 of the unit’s Panther tanks had already broken down, an all-to-common occurrence for the Panther, leaving 22 tanks for the attack. One stossgruppe (assault group), commanded by Senior Lieutenant Strauch, formed the eastern arm of the advance, assigned to relieve a battalion of 559. Volksgrenadier-Division. This unit became trapped in Briey by the day’s fighting. Strauch led a company each of tanks and infantry with a platoon of engineers in support. With the relief completed, the stossgruppe would secure the town. Col. Bäke led the second group with most of the brigade’s armor and men, two companies of tanks and three of infantry. As before, a company of infantry and the brigade’s tank destroyers formed a reserve while the flakpanzer anti-aircraft guns protected the headquarters.

The US 90th Division occupied defensive positions about nightfall on September 7. Its three regiments deployed in a line with the 359th Infantry in the north around the village of Xivry-Circourt and the 358th Infantry around the village of Mairy. Two battalions of the 357th Infantry set up for the night at Avril, but that regiment trapped a battalion of the 559. Volksgrenadier-Division in Briey and left one battalion, 2/357, to surround the German force and finish it the next day. The division commander, Gen. McLain, positioned his command post (CP) far forward so it could remain there the following day, as frequent movements hindered his ability to control his units. This placed the division’s CP right among the forward infantry regiments in some woods, called the Bois le Rappe west of Mairy. The division’s artillery headquarters set up in a farm field to the east, across a road which led toward Mairy. The two headquarters were perhaps a mile apart. Since the division command post was perilously close to the front lines, Company A of the 712th Tank Battalion posted Sherman tanks around both command posts to provide security. McLain and his troops were unaware that a reinforced German panzer brigade was readying itself to attack their positions.

Lacking intelligence, the Germans were likewise unaware of the locations of those American positions, knowing only the places that were their objectives. Col. Bäke’s group set out along the road network leading from Audun-le-Roman toward Mairy with 4 or 5 Panthers under Senior Lt. Struck, followed by a platoon of half-tracks commanded by Senior Lt. Papke. The rest of the stossgruppe followed, with Bäke and his headquarters company right behind the lead elements. They moved southwest and then south on the road, reaching the village of Mont, where they got on the road to Briey to rendezvous with the other stossgruppe.

The road to Briey was the same road which ran between the 90th Division’s command post and the division artillery headquarters. Struck and Papke led their platoons right between the two American positions without spotting them but Bäke and the headquarters company stopped in between them at about 2:30 am. Their reason for stopping is unknown, but GIs involved in the battle surmised the Germans saw a sign posted for the artillery command post and stopped to investigate. Overhead, clouds floated in the cool night air, obscuring the moon and dimming its pale light.

A short distance from the road, the tank crews from Company A of the 712th silently perched on each side, looking at the column in between them. They soon realized it had to be German. Tank driver George Bussell remembered, “I could tell by the tracks it wasn’t ours. The noise was altogether different. They had steel tracks and we had rubber.” Bussell watched the German column stop and could make out the head of an enemy tank commander appear from the hatch of a Panther. “The 90th Division had a sign there…Red and White, it read 90th Division Artillery CP and that’s what the tank stopped and was looking at.”

2nd Lt. Harry Bell commanded three M4s guarding the division CP. As he looked out into the gloomy distance at the German column, he spoke into his radio microphone, reporting the enemy’s location to 1st Lt. Lester O’Reilly, Company A’s commander. O’Reilly asked Bell if he was positive the column was German. Bell said he was sure, and O-Reilly replied, “Give ‘em hell.”

Taking careful aim, the gunner on one of the M4s guarding the artillery CP pressed the foot pedal serving as the trigger for the Sherman tank’s main gun. The cannon boomed, its muzzle flash lighting the night for a moment as its round smashed into a German half-track at the rear of the column. The vehicle burst into flames, illuminating the area and tragically revealing the location of the tank that just destroyed it. Several Panthers fired at it, and the Sherman exploded, spraying deadly metal fragments into the artillery CP—killing and wounding several additional men.

Nearby, another Sherman driver started the tank’s engine. The noise drew the attention of another Panther crew, who hit the American tank in the suspension with its first round. On another Sherman, gunner Sgt. George Colton sent an armor-piercing round straight into one of the Panthers, setting it ablaze just seconds before German fire disabled his tank. Colton climbed out of his stricken vehicle, ran to a nearby Sherman and took over its cannon. He put a second Panther in his sights and slammed another armor-piercing round into it. Now there were two American and two German tanks burning, the light of their flames providing more illumination for the gunners on each side. The uneven staccato of muzzles flashes added to the general chaos and soon two more Shermans burst into flame.

GI Jim Gifford also joined the melee. “In the moonlight there was a column of tanks. There was a blacktop road there and we had tanks on both sides of it.” He told his friend E.L. Scott to grab a bazooka and the pair moved to the road. “We were going to wait for that one tank and blast him…. Scott was pretty cool, he had it on his shoulder and we fired…he turned and started firing at us, and the next thing there were tanks firing all over the place in the moonlight.”

While the Americans tried to organize a defense, the panzergrenadiers dismounted their halftracks and attacked toward both CPs. Several of the half-tracks carried triple 20 mm cannon; they moved to the artillery CP’s flanks and opened fire, joined by the machine gun teams of the German infantry. The American headquarters personnel fought back but took heavy casualties. The GIs repelled the first assault, but another came at 3:45 am, Panthers supporting the infantry with a barrage. Each side pelted the other with grenades. Private George Briggs climbed onto an abandoned tank and manned its machine gun, firing bursts at the Germans in the dark.

The hard-pressed divisional CP had to be partially evacuated, the principal staff sent to the 359th Regiment’s headquarters. The assistant division commander, Maj. Gen. William Weaver, had to convince Gen. McLain to leave. “Ray McLain loved to fight, and he was going to stay and slug it out personally. But he was persuaded, after much argument, with the fact he had to direct the affairs of the whole division, and not just the HQ defense platoon. He departed grudgingly.” McLain did order reinforcements to join the fight; the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 359th moved in from the north, joined by C Company of the 712th Tank Battalion.

Bäke divided his stossgruppe into smaller elements in order to infiltrate through the American positions. However, this caused the smaller groups to run into other American units in the dark. One group ran into D Company of the 712th south of the command posts. This was the battalion’s light company, equipped with the smaller M-5A1 Stuart tank. That unit later reported “…an enemy column, consisting of about 5 Panther tanks and 6 half-tracks, moved down a road between the [American tank] companies, circled the [712th] Battalion area and was believed totally destroyed. The presence of this company was known, but to fire on it in the darkness would endanger our own troops.” Whether the German column was destroyed is unknown, but the statement only highlights the confusion of a night battle.

Whether the same German column or another, C Company of the 712th also encountered the enemy that night. The company bivouacked near the road with the battalion’s Service Company on the other side. This outfit, containing the unit’s mechanics, had a small hill between them and the road the Germans moved along. Several of the men stood guard on the hill, taking their bedrolls with them so they could take turns on watch.

Mechanic Eugene Sand was one of the sentries on the hill. When that column came through there,” he recalled, “C Company started shooting at them and everything they missed in that column landed on the hill where we were.” Sand and his buddies grabbed their bedrolls and ran down the opposite side of the hill to escape the firing. One soldier, Adam Kochan, had an alarm clock with him, used to tell time at night because it had a white face and black hands. As he ran the alarm clock went off, ringing all the way down the hill.

Ray Griffin of C Company was not involved in the exchange of fire on the road. His platoon was sent to reinforce the Artillery CP. After arriving the tank crews camouflaged their M4s with tree branches and waited for the dawn. He later wrote “When it did get light enough to see that the tanks at the bottom of the hill were indeed German…. I had my gunner, Bob Gladson, lay our gun on the closest German tank. Our 75-mm AP round bounced off…my loader Andy Rego, reloaded and we fired again with the same result. I believe we fired 3 or 4 rounds of armor piercing ammo … none of our rounds caused him any damage.” The German tankers spotted Griffin’s tank and returned fire. A round hit the M4, which began to burn. Luckily, the entire crew escaped without injury.

Other C Company tankers engaged the Germans with more success. Don Knapp commanded an M4. He saw a tank near his own hit by a Panther positioned some 2,000 yards away. The range was too far for the Sherman to effectively return fire, so they moved to cover. Minutes later Knapp’s tank joined several others setting up “…in hull defilade,” he remembered. “Okay, so here come some more tanks down the hill and they didn’t even see us. And we nailed them. We were all firing…I think we caught a Panther, somebody did, and it was on fire. And there was an explosion. There was a smoke ring coming out of it and at the same time out of the turret was a German in that black outfit. It blew him right out of the tank and he almost went through that smoke ring.”

Another German force approached Service Company after dawn. Forrest Dixon, a maintenance officer, climbed into a Sherman under repair and missing its engine. It did have battery power. He felt he had to act, since the battalion’s ammunition and fuel was there, and they could not afford to lose it. Most of the mechanics ran when they saw the German tanks approaching, but one soldier stayed and helped Dixon get the 75 mm gun loaded, but there was only one round in the ready rack. Since the M4 had power, he could traverse the turret, but Dixon realized the sight was probably not aligned with the barrel, known as “boresighting.” He decided to wait until the German tank got closer.

“I kept it pointed at the lead tank and when it got about 50 yards from me, that’s when he saw me and began to turn to get his gun in my direction, and I let him have it,” Dixon said. He knocked out the Panther but was now out of ammunition. He grabbed the radio and called Sam Adair, who commanded the 712th’s assault guns, Shermans equipped with a 105 mm howitzer in place of the 75 mm gun. They quickly appeared and when the Germans saw them coming, they all surrendered.

Medical officer Capt. Jack Rediff watched Dixon knock out the Panther. “This German lieutenant gets out, one of his arms was badly injured.” Rediff treated the man’s wounds, speaking to him in broken German. He told the now-prisoner the war was over for him. The German did not like that but asked “Which bone is it, doctor, the radius or the ulna?”

The “Battle of the CPs” proved a chaotic fight, armor and infantry dueling in the dark. Despite this confusion, the Germans realized the situation was not unfolding as they expected. Bäke, while an experienced veteran, learned his trade on the Eastern Front. There, fighting the Soviets, time and again he saw his enemies break and run when a German panzer column penetrated their lines. Despite the breakthrough, here in the West the GIs refused to retreat. Instead, groups of American troops rallied and counterattacked. While these attacks often lacked coordination, the US infantry pressed the Germans hard, preventing them from regaining their momentum. The 90th Division did not panic.

Recognizing the difficulty of the situation, at 08:35 am Bäke ordered his stossgruppe to turn east, back toward German lines. Briey was too far to expect they could reach it without taking excessive losses. Bäke also contacted the other stossgruppe under Lt. Strauch, located to the east. Strauch’s column had not yet contacted any American forces as it moved south from Auden-le-Roman. He ordered them to turn west and rendezvous with him to support their retreat. This pointed Bäke’s force directly at the village of Mairy, situated in a depression surrounded by hills, just a few miles away.

The Germans moved through a small valley between two hills just west of the village, straight towards the U.S. 358th Infantry’s 1st Battalion, commanded by Major Cleveland Lytle. The 2nd Platoon of B Company, 607th Tank Destroyer Battalion supported the unit with four 76 mm towed antitank guns. The Americans received a report of 100 tanks moving toward them and prepared for the worst. Soon the Germans appeared, formed into an arrowhead formation to punch through the American lines. The GIs watching the German approach saw a T formation, though the road the Germans followed was sunken, constraining their ability to maneuver. Major Lytle wrote “The tanks and the many armored transporters were camouflaged with brush, and it really looked for a while like that report of 100 tanks was no exaggeration.”

While the true number was nowhere near 100 tanks, a number of Panthers led several dozen half-tracks straight toward 1/358’s motor pool. Several of the half-tracks carried 75 mm infantry guns used for close fire support. Lytle ordered Lt. Major, his artillery liaison officer from the 344th Field Artillery Battalion, to be ready to fire danger-close fire missions, “to paste the enemy column with all the artillery he could get, regardless of how close he had to shoot to our own troops.” As the liaison officer prepared a barrage, Lytle’s infantry helped trap the Germans under it. Company A’s commander, 1st Lt. Cud Baird, picked up a bazooka and went after the lead German tank. He succeeded in knocking it out at a narrow spot in the sunken road, forcing the German column to stop for a few minutes, long enough for the artillery to open fire.

As the tanks and half-tracks struggled to get around their disabled lead vehicle, the American artillery crashed down around them. Over 300 rounds of 105 mm and 155 mm high explosive hit the Germans, blast pummeling them and shrapnel piercing the thinner armor of the half-tracks and the flesh of the soldiers within. The regimental cannon company joined in, firing directly over open sights. A few antitank guns added their weight to the fray alongside the infantry’s bazookas and mortars. Even the occasional rifle grenade arced into the German formation. The maelstrom of gunfire tore the German column apart; within minutes three tanks and thirty-one half-tracks lay destroyed or disabled.

Some of the American infantry had positions on a hill overlooking the action. Private Ramon Subejano recalled his company commander, Captain Harold Bergdale, appeared before the Germans arrived and told his men to get ready to move out. Minutes later, he returned and told them to dig in, as he had just learned of a German armored force getting ready to attack. Before Bergdale left, Subejano remembered the officer saying, “When the German go in counterattack, you all just lay down and turn around and shoot.” He was essentially telling his men to let the attacking Germans pass by and shoot them from behind.

During the morning Subejano watched the German column’s attack and subsequent destruction. He sent word to nearby tank destroyer gun crews about targets and to his fellow infantrymen about advancing enemy troops. Later in the morning he saw a staff car carrying two German officers racing toward him. He did what his captain told him; Subejano lay down, let the vehicle go by and then shot each German in the back. Both died and their vehicle crashed into a ditch.

With their vehicles lost, many of the panzergrenadiers dismounted and tried to assault into Mairy. Those at the back of the stricken column tried to retreat while a handful of Panther tanks moved to a hilltop providing a direct line of fire into Mairy. The American anti-tank guns returned fire, hitting two of the German tanks and driving the rest away. At 10 am a group of panzergrenadiers in 17 half-tracks managed to get free of the main column, flanked to the south and got into the town. They had a single Panther tank positioned in the middle of their column.

Again, the Americans were ready. The column came close to the 105 mm howitzers of the cannon company, which blasted two half-tracks with high explosive shells. Several men from the tank destroyer platoon took up bazookas and destroyed two more half-tracks. The German column got moving again, trying to retreat out of town to the north, but soon lost four more vehicles to antitank guns. This included the lead and trail vehicles of the column, leaving the survivors trapped. A rifleman shot the Panther tank’s commander as he raised his head out of his hatch. Further small arms and machine gun fire raked the burning column as mortars bombs dropped on it. Finally, the surviving German troops decided it was enough. A white flag appeared at the rear of the column; 209 soldiers surrendered, of which 65 were wounded. An unknown number died in the short battle.

While the main strength of the column suffered defeat at Mairy, the rest of Bäke’s Stossgruppe ran into various elements of the 90th Division. GIs from the 359th Infantry arrived at the divisional CP and repelled several attacks by small groups of infantry and armored vehicles. A few miles south, the CP of the 712th Tank Battalion went through several more attacks over the course of the morning. A report from D Company described an attack at 10 am: “…two enemy Panther tanks broke through our defenses and moved full speed toward the Company and Battalion Headquarters Company area. Guns from several directions opened up on them and destroyed both tanks before they had done any harm. Five P.W. [Prisoners of War] were taken, one of whom stated they were trying to get out instead of in.” The panzer brigade was paying for the lack of training of its soldiers.

At the CP of the 607th Tank Destroyer Battalion, a lone tank appeared, threatening the unit’s rear echelon. A 76 mm gun fired on it, but the tank quickly changed direction and got out of the antitank gun’s line of fire. Lt. Elliot Schechter led a squad of men after it. They crawled to within a hundred yards and hit the lone armored vehicle with a rifle grenade or a bazooka rocket. A few soldiers fired their carbines as well; it proved enough to shock the crew into abandoning their vehicle. The GIs gave chase and wounded one of the Germans. The rest surrendered.

Small groups of Germans tried to get through the American lines and back to Audun-le-Roman, leading to scattered fights throughout the area. In one case, even an artillery spotter plane got involved. An L-4 Piper Cub of the 915th Field Artillery Battalion overflew the area, piloted by Lt. George Kilmer and carrying Lt. George Pezat as an observer. As the pair looked for German targets to attack with artillery, they spotted a lone Panther tank moving north. Using their radio, they repeatedly tried to catch the tank in a barrage of high-explosives and steel.

Hitting a moving target is difficult, however, due to the delay between the time the artillery fire direction center received the call and when the shells roar downrange. Each time the tank avoided the incoming fire as it kept moving. The two lieutenants grew so frustrated by their inability to knock out the tank they began buzzing it with their light plane. Each time they fired their .45 caliber pistols at it, a hit sending the comparatively tiny bullet bouncing off the Panther’s thick armor. After an hour, the two fliers broke off their impromptu strafing attack; the plane was low on fuel. The panzer escaped to Audun-le-Roman, one of only a few to get out that day.

A few days later, General Patton visited the area. He later remarked “one of the few tanks to escape was a Panther. I saw the tracks where it had gone straight into our line, oblivious of what we could do to stop it, and then turned sharply left on a road leading to Germany. It disappeared in a cloud of dust and sparks where our tracers were hitting it.” Other German vehicles and infantrymen made their own escapes, not all of them successful. The other Stossgruppe under Lt. Strauch lost contact with Bäke’s force at 1:30 pm. This German force soon ran into the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, supported by a few antitank guns. The Germans attacked but were quickly beaten back with the loss of two half-tracks and a pair of Panzer IV/70 tank destroyers. Strauch withdrew his command toward the town of Aumetz at 7 pm that evening. The German attack ended with the shattered and dispersed remains of Panzer Brigade.106, retreating to their lines in defeat.

Despite Bäke’s experienced leadership, his brigade’s attack failed due to poor execution. His untrained troops lacked the experience to carry out a successful spoiling attack against a veteran U.S. division. The brigade’s lack of organic artillery support further reduced its capabilities. German leadership at the army level likewise overestimated the unit’s potential and threw it into a poorly planned attack which would at best only temporarily delayed the American advance. The 90th Division’s after-action report stated the German attack seemed to stumble into the command posts and appeared unaware they were fighting a rear-echelon unit. Several American artillery forward observers stated they saw panzer crewmen running back and forth between tanks carrying messages, even during artillery barrages. They surmised the enemy suffered from radio communications difficulties, another problem for inexperienced units.

For this, the panzer brigade suffered heavy casualties. The 90th Division reported taking 764 prisoners in the battle, including 125 wounded. There is no count of the dead but one estimate places total German casualties at fifty percent, including two battalion and three company commanders. The battalion surrounded in Briey surrendered in the afternoon; this put 442 more prisoners into American hands. Total casualties in the 90th Division totaled eleven dead and sixty wounded, most of them at the artillery CP. The 712th reported four Shermans lost with the rest repairable, but personnel losses are not known. The tank battalion’s performance during the chaotic battle impressed Gen. McLain, and from then the 712th bore the nickname “Armored Fist of the 90th.” Later during the war, when an armored division commander offered the use of one of his combat commands, McLain replied, “No, thank you. I have the 712th Armored Division.”

The American units claimed about forty-nine tanks destroyed between them, along with fifty-four half-tracks and over a hundred trucks. These totals are certainly too high; units on both sides typically overestimated such numbers due to the confusion of battle. One German account reported only seven of twenty-two Panthers returned from the battle. A later German report stated their brigade destroyed 143 American tanks and armored vehicles from 6-11 September. This blatant exaggeration was likely to cover up the brigade’s defeat and heavy losses. These high numbers do not appear in the brigade’s diary, so it was probably added by a higher headquarters. Within days the battered German unit transferred to Luxembourg. The 90th Division resumed its advance the same day as the battle and by September 13 reached the banks of the Moselle River.