By Sam McGowan

In the summer of 1944, the Third United States Army under Lt. Gen. George S. Patton made a spectacular dash across France, a daring advance that ranks high on the list of great military endeavors. To a large extent, the gains made by Third Army were possible only because of the cooperation between the ground units and air units of the XIX Tactical Air Command (TAC).

More so perhaps than anyone else, Patton knew how important the young fighter-bomber pilots and their Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and North American P-51 Mustangs were to the success of the operations he planned for his army. Few, except perhaps the young men in the tanks and those fighting alongside them on the ground, realized just how detrimental bad weather that kept the fighter bombers on the ground could be. But the Germans knew and they planned their movements to avoid the deadly “Jabos,” as they called the Allied fighter bombers.

Third Army had learned how air and fast-moving armor could complement each other and allow a particularly audacious army to quickly overwhelm and defeat superior forces. During the Louisiana Maneuvers of 1941, Third Army demonstrated just how effective the combination could be as armored forces supported by air moved so fast and occupied so much territory that umpires were called to question the legitimacy of the tactics.

Third Army’s success enhanced the reputation of its commander, a German immigrant named Walter Krueger. Krueger’s “sledgehammer” in the campaign that drove his Second Army adversaries all the way to Arkansas was the 2nd Armored Division, which would later earn fame as the “Hell on Wheels” division. The division’s success in the maneuvers was largely due to the leadership of its commander, a man whose basic philosophy was to always be audacious, Maj. Gen. George Smith Patton. Three years later Patton became Third Army’s commander when it arrived in England. He brought with him his tremendous respect for air support and plans to use it to enhance the power of his new army.

Marshall and other senior Army officers were well aware that, in spite of his faults, the flamboyant and often outspoken officer was the most effective ground commander in Europe, and probably in the entire U.S. Army. Once Allied troops had secured a beachhead in Normandy and managed to make their way off of the beaches, there would be a need for a hard-driving army led by a particularly dynamic commander who knew how to exploit the military advantage and defeat the enemy.

Third Army had remained in the United States during the early years of the war as many of its commanders and key staff officers went overseas with other units. Walter Krueger went to the Pacific, by personal request of General Douglas MacArthur. Krueger’s replacement proved far less effective, perhaps due to his policy of delegating too much authority to his chief of staff, leading Marshall to decide that he was not the man to lead Third Army in combat. When Third Army arrived in England, the troops were unexpectedly greeted by Patton, their new commander. Patton immediately initiated a shakeup in the command structure and began emphasizing his thoughts on tactics, including his belief in the importance of air support. The air unit responsible for support of Third Army was to be the XIX Tactical Air Command.

The XIX Tactical Air Command was one of two special commands that were planned for the Ninth Air Force, an air unit that was organizing in England in early 1944 to provide support to the ground forces during and after the Normandy landings. In addition to the typical fighter, bomber, and troop carrier commands, Ninth Air Force was to include two tactical commands, the IX and XIX, each of which was to be dedicated to an army. The IX TAC was assigned to support First Army, while XIX TAC was dedicated to the support of Third Army. Both commands were equipped with several combat groups flying single-engine fighter bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. The mission of the fighter bombers was to maintain air superiority over their respective ground force and to provide close air support for the armored and infantry divisions.

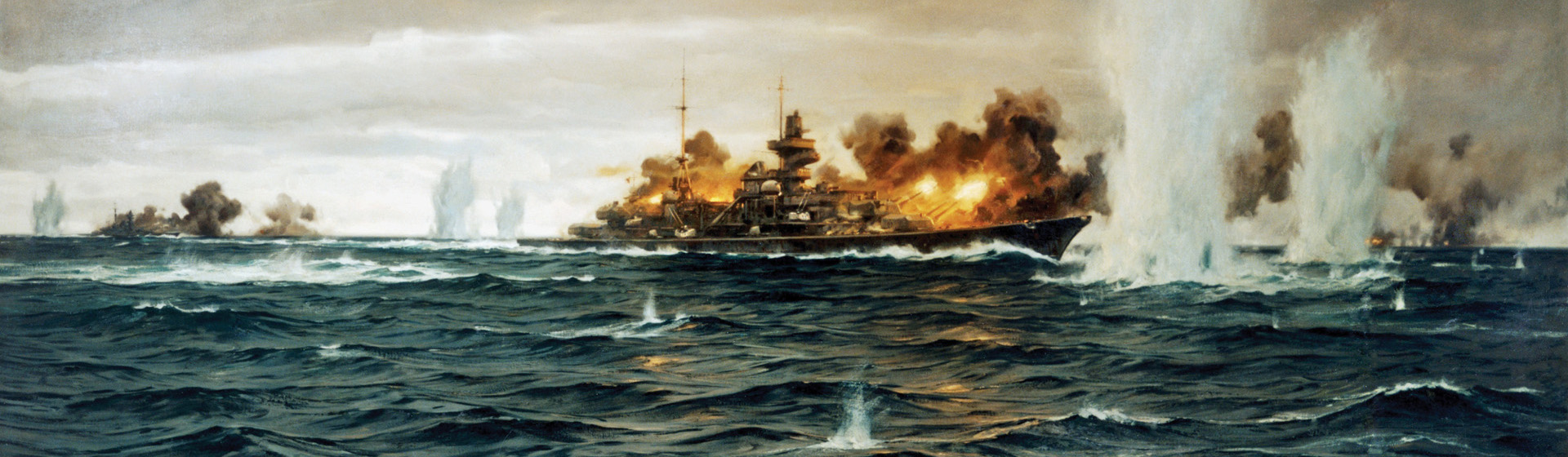

The close air support mission was not new in 1944, but the Ninth Air Force and the Royal Air Force II Tactical Air Force would refine it to a high state of the art. Luftwaffe dive-bombers and light bombers had played a major role in the German blitzkrieg strategy in the early years of the war, and Allied commanders had taken note of their employment.

U.S. Army pilots became proficient in ground attack in New Guinea in the summer of 1942 and Army and Marine fighter pilots adopted the tactic in the struggle for Guadalcanal. The British Western Desert Air Force made ground cooperation a major RAF mission in North Africa, then taught the tactics to the American fighter pilots who joined them. Patton himself had become familiar with the possibilities afforded by air power in support of ground units in North Africa and Sicily. Perhaps no other commander was better acquainted and more appreciative of air power than Patton.

Planning for the Normandy landings called for the creation of two tactical air forces to support the invasion and to provide air support for the ground forces once they were ashore. The RAF established the II Tactical Air Force from its Ground Cooperation Command and the U.S. Army Air Forces established the Ninth Air Force in England as a tactical unit. The Ninth had formerly served in North Africa primarily as a heavy bomber force, operating long-range Consolidated B-24 Liberators on missions against targets in North Africa and the Mediterranean. Under the Overlord plan, the II Tactical Air Force would provide support for Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s Twenty-First Army Group, while the U.S. Ninth Air Force would be responsible for supporting Lt. Gen.l Omar Bradley’s First Army Group.

Overlord called for First Army to hit the beaches at Normandy along with the British II Army, with both armies under Montgomery’s overall command. Third Army would initially remain in England, then would begin moving to Normandy between D+15 and D+30. Third Army, code-named Lucky, began moving to the Normandy beaches on D+29, July 6, 1944. Patton set up his command post near the Norman town of Nehou, about 15 miles south of Cherbourg and just inland from Utah Beach. Brig. Gen. Otto P. “Opie” Weyland, commander of XIX TAC, set up his command post adjacent to the Lucky command post. The Third Army staff also included its own air intelligence and planning sections.

Lucky’s initial mission was to break out of the Normandy beachhead and capture Brittany, the French region south of Normandy, and to open its seaports to Allied shipping. Once Brittany had been liberated, Third Army was to either drive east toward Metz and the Saar or make a sweep south of the Loire River. Third Army was set to become operational on August 1, as was XIX TAC. Even though Third Army headquarters was in Normandy, all of its assigned units were not. Some units were being held in England awaiting equipment while others were making the move to France. The XIX TAC’s combat groups were also still in England, although IX TAC had moved most of its fighter bombers to Normandy.

Initially, XIX TAC included three fighter bomber groups, two equipped with Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and one with North American P-51 Mustangs, but the number of assigned groups varied due to the dictates of the military situation. Immediately after the Third Army breakout from Avranches, the number of groups assigned to the XIX TAC increased to nine, mostly with P-47s. Although the P-51 is often touted as the best Allied fighter of World War II, in reality the P-47 was the best-suited for the fighter bomber role. The P-51 was equipped with an in-line liquid-cooled engine that could be put out of action by a single round, but the P-47s air-cooled radial engine could absorb a lot of punishment and keep running long enough to bring the pilot back home.

The Thunderbolt was also the better armed of the two, featuring four .50-caliber machine guns in each wing compared to the Mustang’s three. Eight streams of .50-caliber bullets threw a lot more weight than six, which made the P-47 the more effective strafer. Consequently, P-51s were often used to provide an air umbrella over the battlefield to keep German fighters at bay as the P-47s went in low to attack German armored columns with rockets and bombs.

In mid-July, Patton’s intelligence staff reported that German opposition in Brittany was far less than expected, while the armored strength opposing the invading forces was almost 900 less than previously estimated. Furthermore, most of the German armor was concentrated in the Bocage-Caen sector opposing Montgomery’s Twenty-First Army Group. Patton proposed to Bradley that he be allowed to mount an attack with two armored divisions and two of infantry even while his army was still assembling in France. Bradley began working on a plan of his own to initiate a breakout from the beachhead.

On July 22, Patton was called to confer with Bradley at the headquarters of the newly formed Twelfth Army Group, which had replaced the former First Army Group as part of a deception plan to keep the German 15th Army in the Pas de Calais. Bradley gave Patton the outline of his plan to break out from the beaches. British and Canadian forces under Montgomery would attack to the east and south around Caen, while First Army would launch Cobra, an attack to the south around St. Lo.

The VIII Corps, which was actually part of Patton’s command, was to drive south down the coast to open a window for Third Army to launch an attack into Brittany. In advance of the attack, a massive aerial and artillery bombardment would pound German positions around St. Lo. Some 3,000 heavy bombers, medium bombers, and fighter bombers were involved in the attack, which was successful in that it paved the way for First Army’s breakout. Unfortunately, the bomb line was compromised by “creep back” as the impact points for the falling bombs moved northward into the American lines. Hundreds of GIs were killed by bombs dropped by friendly planes, including Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair, commander of the U.S. Army Combat Command and the senior U.S. Army officer in France.

On July 28, Bradley made Patton personally operational by declaring that he was now deputy commander of Twelfth Army Group. Patton was instructed to take command of VIII Group’s sector and to set his breakthrough plan into action. The position allowed Patton to put his plan in motion so that Third Army would be on the move the instant it received operational status.

On July 31, the day before Third Army was to become operational, Patton met with his staff and key commanders just before their departure for a new command post close to the lines. At the conclusion of the daily briefing, the Third Army commander admonished his officers regarding two of his dearest principles: that the way to reduce casualties was to constantly push the enemy and that worrying about protecting flanks was a waste of time. This was a refrain Patton had maintained with his staff since taking command of Third Army. He frequently reinforced his lecturing on the futility of worrying about protection of flanks by pointing out that the XIX TAC would protect them. It was a belief he took to heart.

That evening VIII Corps broke through at Avranches. When the commanding general notified Patton that his men were on the banks of the Selune River, Patton ordered him to establish a bridgehead immediately. He then launched a two-pronged Third Army attack into Brittany—one aimed at the provincial capital of Rennes and the other at the coastal city of Brest. He set up Task Force A to mop up along the north coast of the peninsula.

The XIX TAC role in the Third Army breakout was limited during the first hours because of bad weather in England that kept the fighter bombers on the ground until noon. Although the IX TAC’s fighter bomber groups had made the move to France, no airfields had yet become available for Weyland’s command. Once the fog lifted and the fighter bombers were able to take to the air and arrive over the battlefield, they were in sunny skies and able to make a difference by bombing and strafing German positions and columns. The fighter bombers also provided air cover and often tangled with German planes in the air.

Third Army itself was not immune to air attack. During the first few days of operations, the Luftwaffe was very active in the Third Army area. One German attack was aimed at a bridge near Avranches and a nearby dam, but antiaircraft fire managed to prevent a successful attack. Many of the attacks came at night, which prompted the assignment of a squadron of Northrup P-61 Black Widow night fighters to XIX TAC for night patrols. The P-61s were also adapted to use their radar for the night interdiction role. Third Army captured most of Brittany within three days, and Patton turned his eyes toward the rest of France. The XIX TAC P-47s and P-51s struck at pockets of German resistance.

Patton benefited from a bit of timely intelligence provided by a XIX TAC pilot, who was shot down near Angers, a village on the Loire River some 55 miles south of Laval, which at the time marked the limit of the Third Army advance. He was picked up by French guerrillas and transported over back roads to Third Army lines. During his debriefing, the pilot reported seeing few Germans, and those were signal troops pulling down communication lines, then moving to the east. This was solid intelligence that the Germans were retreating. He also reported an intact bridge over the Loire River just south of Angers.

Patton immediately dispatched a 5th Infantry combat team to capture Angers and secure the bridge. The team surprised the German garrison at Angers and captured them before they could organize a defense, but the bridge had been mined and was blown before it could be seized. Nevertheless, the seizure of Angers was a great opportunity. Patton immediately ordered XX Corps, which had been standing by awaiting commitment, to move to Angers, then advance eastward along the north bank of the Loire to secure Third Army’s south flank. This move set the stage for the operation that doomed German hopes in Normandy.

On August 7, the Germans counterattacked. Luftwaffe bombers hit Patton’s command post on the night of the 6th, but failed to do significant damage. A more serious attack struck an ammunition dump a few miles away; the fires burned for two days. The counterattack was aimed at the 2nd Armored Division at Mortain, on the demarcation line between the First and Third Armies. It was a powerful attack, involving 23 divisions, five panzer and 17 panzergrenadier. Some of the German divisions had been shifted south from in front of the British and Canadians, who had only managed to advance a few miles due to strong opposition.

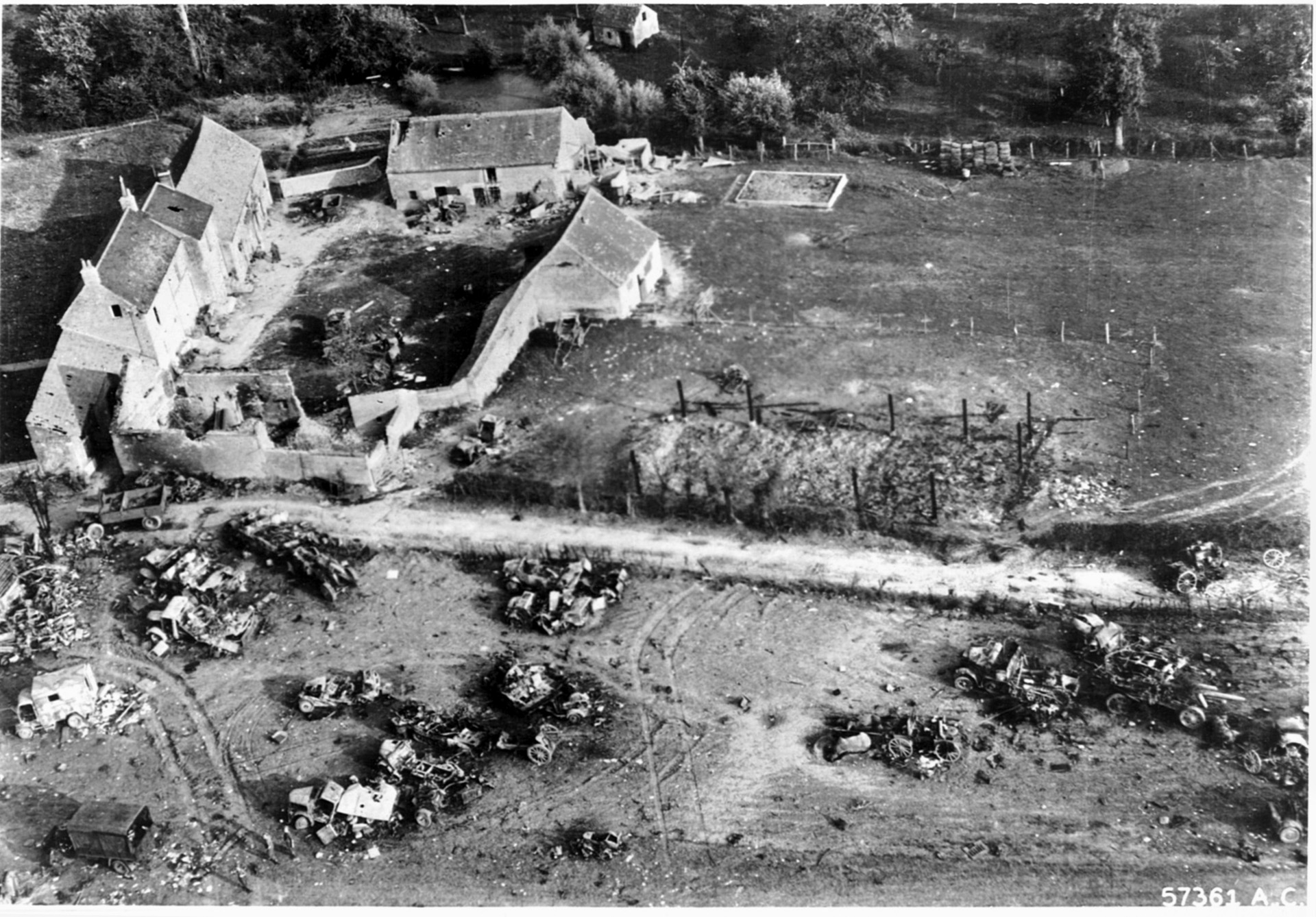

The German attack ran smack into the fighter bombers of the IX and XIX Tactical Air Commands. The dreaded “Jabos” ranged far and wide over the battlefield, literally attacking anything that moved—motorized vehicles, tanks, locomotives, horse-drawn carts, individual soldiers on bicycles and on foot. By the time the Germans began their withdrawal, all but two of the bridges over the Seine north of Paris had been knocked down and rail and road traffic was practically at a standstill.

On August 8, the XIX TAC launched 717 sorties. The fighter bomber pilots put in claims for three bridges, 29 locomotives, 137 freight cars, 505 motor vehicles, 93 horse-drawn vehicles, and 29 tanks. The P-47s and P-51s also cut 11 railroads and flew three strafing raids on German airfields around Paris. Hundreds of sorties were flown in support of attacks by Third Army armored columns. The carnage on August 9 was even greater as the XIX TAC flew 780 sorties that were as destructive as those the day before. This time the fighter pilots included 16 claims for aircraft destroyed in addition to scores of German vehicles and locomotives. The XIX TAC losses amounted to 13 pilots, four on the first day and nine on the second.

Just how effective the fighter bomber attacks were is evidenced by the reports in the German war diaries. One panzer commander told how his division advanced more than 10 miles with only three losses, then all of a sudden the Jabos dropped out of the sky firing deadly rockets and strafing, spreading terror throughout the ranks. The panzers were helpless under the onslaught. Tanks and trucks were quickly turned into smoldering wrecks, and the previously rapid advance turned into debacle as the roads became blocked by burning vehicles.

The German Seventh Army diary recorded how the counterattack came to a standstill under the deadly attacks. The Germans were further frustrated by the absence of the Luftwaffe, which was prevented from providing air support to the panzers by the umbrella of XIX TAC P-51s that covered the battlefield. By August 11, the German attack had been broken and the outcome of the war in Europe had all but been decided.

The capture of Angers put Third Army into position to attack northward at the back of the German 7th Army and completely envelope the entire German force in Normandy. On August 11, elements of Third Army captured Alençon, cutting the highway leading north to Argentan. With Alençon in Allied hands, the Germans realized they were in danger of being completely cut off and began milling around. A XIX TAC P-47 squadron spotted 800 to 1,000 motor vehicles driving aimlessly around just west of Argentan and went in for the attack with bombs and guns, firing until exhausting all of their ammunition. The XIX TAC pilots claimed an estimated 400 to 500 vehicles burned out or blown up during the action. After dropping all of his bombs and exhausting all of his ammunition, one fighter pilot dropped down low and jettisoned his gasoline-filled belly tank on a line of 12 trucks. He saw them go up in flames in the exploding gasoline.

Elements of Third Army had advanced to within a few miles of the town of Falaise, which lay some 18 miles northwest of Argentan. The Germans had been routed, and XV Corps had the tanks and troops to seal off their escape route. At this point military politics reared its ugly head. SHAEF—meaning Eisenhower—ordered Patton to halt his forces at Argentan. Field Marshal Montgomery’s British and Canadian forces would advance and take Falaise. Patton was told to set down the American 90th Division and 2nd French Armored Division in the vicinity of Argentan and to send the bulk of XV Corps some 50 miles eastward toward Paris to capture the town of Dreux and the nearby airfield.

Eisenhower’s explanation for the halt was that the British had sewn the area around Falaise with time bombs. This, however, was a ruse. The real reason for the halt was that Montgomery had insisted on capturing Falaise himself and put pressure on Ike to halt Patton’s forces at Argentan. Montgomery took his time moving forward, and it was not until August 19 that the Falaise Gap was finally closed. Meanwhile, what was left of the German 7th Army escaped.

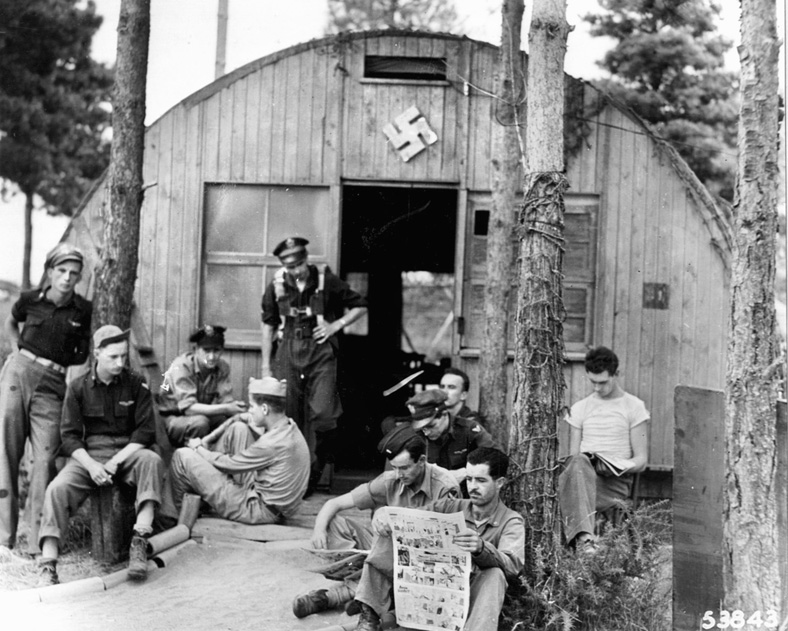

embarking on a mission in France.

The Germans suffered horribly during their retreat through the Falaise Gap, but they managed to move the bulk of their panzer divisions out of harm’s way intact. They took advantage of darkness to avoid the Jabos and moved the panzers through the gap, while replacing them with lesser troops brought in from the east. Most of the German losses fell to the fighter bombers, as XIX TAC squadrons shot up everything that moved by day. They were joined by the IX TAC, as well as British Typhoons and Spitfires from II Tactical Air Force.

So many fighter bombers were thrown into the fray that they had to queue up and wait their turn. One flight of P-47s from the 405th Fighter Bomber Group captured some 400 German POWs. They attacked the column so relentlessly that the survivors began waving their handkerchiefs in surrender. The fighter pilots herded the Germans toward some nearby tanks, whose crews took possession of the POWs.

Although Third Army was halted at Argentan, its direction of attack merely changed. Patton’s line of advance was already some 60 miles west of the Falaise Pocket, stretching along a 60-mile line running south from Dreux to Orleans. Paris lay barely 30 miles to the east. The close proximity of Third Army forces to Paris put XIX TAC fighter bombers into frequent contact with the Luftwaffe, which maintained several airfields in the vicinity of the French capital. Fighter bomber missions by the tactical commands were officially classified as armed reconnaissance or armored column cover, but they frequently were aimed at German airfields. During a two-week period commencing in early August, XIX TAC fighter bombers engaged in aerial combat every single day but one, in spite of bad weather on five of the affected days. The fighter bomber pilots were just as aggressive—perhaps more so—as their peers flying P-51s in the escort squadrons of the VIII Fighter Command.

On one occasion, when a squadron of P-47s from the 405th Fighter Bomber Group encountered a formation of Germans, they tore into them using the rockets mounted on pylons beneath their wings for ground attack. The Germans were caught by surprise by the unorthodox tactic and broke up their formation. When four 405th Group P-47s were jumped by 16 Germans, all four P-47s were shot down, but they accounted for three of the enemy. An eight-plane flight of P-51s from the 354th Group attacked a huge formation of 70 Focke Wulf FW-190 fighter bombers on their way to attack Third Army columns. The P-51s only accounted for two German fighters, but they broke up the formation and kept them from carrying out their mission.

Another flight of P-51s engaged in a similar encounter when they spotted a flight of 20 Germans. The P-51s climbed above the German formation, but they were coming down to attack, some 60 German fighters bounced them. Over the next 15 minutes, the battle ranged from 11,000 feet down to the deck. Eleven Germans went down while the XIX TAC lost two.

One of the most amazing encounters saw the loss of two German fighters to a flight of P-47s that had already run out of ammunition! The unarmed P-47s went down on the deck and began maneuvering, causing two Germans to fly into the ground. On August 20, eight P-47s from the 362nd Fighter Bomber Group took on four times their number and came out of the scrap with a score of 6-2, in the Americans’ favor. Four of the six kills were credited to one U.S. pilot.

While the glamour of air-to-air combat captures the imagination, the destruction of enemy aircraft on the ground is also effective. This was a lesson American airmen learned in the Southwest Pacific in mid-1942, and it was taken to heart by the Ninth Air Force fighter bomber groups. Despite the oft-repeated assertion that the air war had been won before D-day, the Luftwaffe was still a major threat to the ground forces in the summer of 1944, and the fighter bomber pilots fought to keep the Germans off of the infantry’s back.

As Third Army dashed across France, XIX TAC fighter bombers endeavored to keep their way clear of the threat of air attack. Most of the German fighter bombers were based on airfields around Paris, and these airfields became targets for XIX TAC rocket and strafing attacks. On August 25, the two tactical air commands, IX and XIX, teamed up for a coordinated attack on German airfields at Beauvais and Reims.

Fighter bombers from the two TAC were credited with the destruction of 127 German aircraft, 77 in the air and 50 on the ground, along with 11 probables and 33 damaged. Some of the day’s battles saw the Germans with superior odds, but the more experienced and aggressive American pilots usually gained the upper hand. One dogfight saw 12 P-51s battling some 45 FW-190s and Me-109s; 13 Germans went down while one U.S. fighter bomber was lost. Total losses for the IX and XIX TAC on August 25 were 27 fighter bombers and 19 pilots. The Allied successes led the Luftwaffe to withdraw from France entirely.

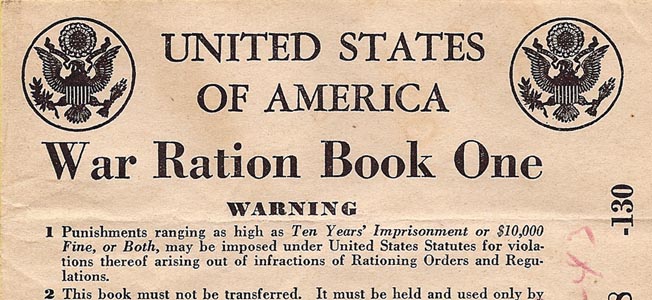

The destruction of the Luftwaffe in France coincided with a new and frustrating threat to Third Army. Patton’s armored columns had moved so far and so rapidly that they had outrun their lines of supply. Fortunately, captured German airfields afforded landing strips for Allied transports loaded with gasoline for the ground forces. Initial supply flights were made by C-47s from IX Troop Carrier Command (TCC), but in early August General Carl Spaatz took the TCC away from Ninth Air Force and put it directly under his own headquarters.

Spaatz justified the decision by pointing to the August 1 creation of the First Allied Airborne Army and the need for the Troop Carrier Command transports to be available to support any airborne operation that might suddenly arise. To compensate for the withdrawal of the some 1,400 TCC C-47s from support of the rapidly advancing ground forces, Spaatz set up the 302nd Air Transport Wing under the control of the Air Services Command of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces, Europe. Still, without the TCC transports, there was not enough air transportation to go around and the assignment of the transports became a political issue at SHAEF.

One of the steps initially taken to keep Third Army moving was the temporary transfer of a number of VIII Bomber Command B-24 Liberators to IX Troop Carrier Command for “trucking” duty flying gasoline to France. The four-engine Liberators operated into recently captured German airfields as close to Third Army’s forward positions as possible. When the TCC C-47s were withdrawn from support of the ground forces, a contingent of 100 Air Transport Command C-47s was transferred from the United States to Europe for assignment to the 302nd Air Transport Wing. Still, there was not enough airlift to keep the motorized columns moving, and Spaatz’s headquarters shifted the transports around.

After the liberation of Paris, transports that had been supporting Third Army were shifted to flying supplies into Paris, leaving Patton’s armored forces literally out of fuel. Third Army would remain in a defensive position for more than six weeks.

Third Army’s rapid advance led the American chiefs in Washington to conclude that the war in Europe could be over by November, but the failure of Field Marshal Montgomery’s ambitious Operation Market Garden in Holland and Eisenhower’s subsequent decision to halt the Allied advance west of the Rhine prolonged the war, nearly leading to disaster. During the six-week halt, Patton was given authority to carry out limited offensive operations to exploit the Third Army bridgehead across the Moselle River. The XIX TAC fighter bombers were particularly busy along the Third Army front since Patton’s role at the time was to draw as many enemy forces as possible to his front.

In the month of October, the XIX TAC flew 4,790 sorties in support of Third Army units, attacking German troop concentrations, gun positions, armor, command posts, and airfields. On October 20, P-47s from the 362nd Fighter Group breached the Etang-de-Lindre dam at Dieuze with 1,000-pound bombs in preparation for an upcoming Third Army advance.

Interdiction of German lines of communication was a major mission of the Ninth Air Force fighter bombers. While the Allied armies remained in check at the Rhine, the XIX TAC was assigned to keep watch on eight railroad lines leading to Coblenz, which lay in Third Army’s front. Prior to October, railroad bridges were left intact, but as it became apparent that the Allied advance was coming to a halt, the restriction was lifted. Rail-cutting missions consisted of attempting to interrupt rail traffic by knocking rails out of the track. Such attacks were temporary interruptions, but they halted rail traffic until the damage was repaired. The XIX TAC missions attacked 33 bridges during the month of October, and pilots put in claims for 17 destroyed.

In early November, Patton’s Third Army began a new offensive by striking against the German flanks around Metz. In preparation for the assault, some 1,000 fighter bomber sorties struck supply dumps and ordnance. Other strikes were aimed at airfields and railroad bridges. November signaled the approach of late fall and winter weather over Western Europe, and as Third Army continued its advance the ground troops were often deprived of fighter bomber support. For 12 days between November 10 and December 15 air operations were totally restricted.

When weather permitted, XIX TAC fighter bombers wreaked havoc among the Germans. During three days in mid-November, more than 1,000 sorties were flown, all against enemy transportation. Claims for the period amounted to 842 motor transport vehicles, 60 armored vehicles, 162 locomotives, 1,096 railroad cars, and 113 guns. Attacks against German positions at Merzig on November 19 led to a commendation from General Patton. In spite of frequent bad weather, the XIX TAC flew 5,195 fighter bomber sorties between November 1 and December 15, while their night fighters accounted for 99 sorties and reconnaissance aircraft went out 563 times.

On December 16, German troops launched their massive attack, starting the Battle of the Bulge, along the lightly defended First Army sector in the Ardennes and commenced an offensive that shook the Allied command to its roots. Although the troops in the sector and the high Allied commanders were taken by surprise, there had been numerous indications in preceding weeks that the Germans were building up their forces in the west. Not the least of these intelligence warnings came from tactical reconnaissance aircraft, including the 10th Tactical Reconnaissance Group from the XIX TAC. Additional information came from fighter bomber pilots operating in front of the Allied lines. But Eisenhower and his headquarters did not believe that Germany had the ability to mount a counteroffensive in the west.

The German commanders took advantage of worsening weather conditions to launch their offensive, knowing that the Allied Jabos would be unable to operate under the low ceilings in the rain, snow, and fog that characterize European winter storms. When the attacks came, Patton’s Third Army was making preparations to move against the Siegfried Line. The German offensive was well to the north of Patton’s area, and he and the air commanders—Spaatz, Ninth Air Force commander Hoyt Vandenberg, and Weyland—hoped that his attack would be allowed to continue.

A worsening tactical situation in the Ardennes and a lack of First Army reserves led Eisenhower to order Patton to break off his attack and send forces northward more than 100 miles to relieve the embattled 101st Airborne Division at the town of Bastogne. To reinforce Weyland’s XIX TAC, three fighter bomber groups were transferred from IX TAC; a few days later each of the tactical air commands received a P-51-equipped fighter group from the Eighth Air Force.

For the first three days of the offensive, weather conditions were marginal and the fighter bombers were able to operate, especially those of the XIX TAC, since weather conditions to the south were better. They met with intense enemy air opposition as the Luftwaffe came out in strength. Encounters with German aircraft often forced the fighter bombers to jettison their bombs so they could engage in air-to-air combat. Beginning on December 19, a severe winter storm enveloped the region, grounding the fighter bombers.

One XIX TAC mission on December 23 was providing escort for IX Troop Carrier Command C-47s dropping supplies to the men of the 101st Airborne at Bastogne. Other missions escorted medium bombers while two groups supported Patton’s advancing troops. Ninth Air Force fighter bombers encountered heavy enemy air opposition, claiming no less than 91 German aircraft destroyed against a loss of 19 of their own. Ground claims were for some 230 motorized and armored vehicles, along with enemy troop concentrations and gun positions.

Favorable weather continued for several days, allowing the fighter bombers to continue their devastating attacks on the German forces, which were beginning to run out of fuel and had failed to capture the Allied fuel dumps they were depending on to maintain their advance. Over the five-day period from December 23-28, XIX TAC aircraft claimed 3,200 vehicles, 293 tanks and armored vehicles, 57 guns, 42 locomotives, 1,800 railroad cars, 11 bridges, five ammunition dumps, 234 buildings, 52 German planes destroyed or damaged and, 106 rail lines cut.

The New Year dawned with a devastating attack on the fighter bomber airfields in Holland and Belgium by Luftwaffe planes. The Germans took advantage of expected New Years Eve celebrations by the Allied pilots, an expectation that was not entirely misplaced. A XIX TAC airfield near Metz suffered losses of 20 P-47s, with 17 others damaged. However, of the 25-plane attacking force, 16 were shot down by antiaircraft fire. Later in the day, XIX TAC pilots reportedly shot down 47 more.

An innovation in the war in Europe was the use of night fighters both to provide protection against air attack and to interdict German supply lines at night. The XIX TAC included the 425th Night Fighter Squadron, an organization equipped with P-61 Black Widow twin-engine fighters that had been armed and equipped for night combat. A few modified Douglas A-20s were also assigned to the night-fighter role. The radar-equipped night fighters patrolled the Third Army area looking for enemy aircraft and for signs of vehicles and movement on the ground.

Another innovation was the use of fighter bombers to drop supplies to ground troops in forward areas. The first for the XIX TAC was the delivery of rations to elements of the 80th Division spearheading the bridgehead at the Sauer River. The first drop mission was carried out in spite of heavy German ground fire, and the experiment was repeated at other Third Army points. Early in the European campaign, light liaison aircraft from Third Army’s own aviation detachment dropped ammunition to a surrounded company.

Bad winter weather often kept the XIX TAC fighter bombers on the ground in the first weeks of 1945. Fortunately, the decline of the German Wermacht after the Battle of the Bulge allowed the armored and infantry forces to prevail without air support, although the ground troops certainly appreciated the contribution of the fighter bombers when the weather cleared. As Third Army made its way slowly forward through melting snow and mud in the Eifel, the XIX TAC struck at the railroads and roads the Germans were depending on to move their troops and supplies.

On March 14, Third Army crossed the Moselle River. The next day was a good one for the XIX TAC as the command flew 643 sorties. The following day Patton began the encirclement of German Army Group G. The devastating attacks by the Jabos not only destroyed hundreds of vehicles and unknown numbers of troops, but they also made German morale a casualty, preventing the enemy from taking advantage of the highly favorable defensive terrain. On March 24, Field Marshal Montgomery launched his epic crossing of the Rhine, which had already been crossed by American troops. Third Army had crossed at Oppenheim two days earlier.

After the Rhine crossing, the Allied armies rushed toward their objectives, which in the case of the American Twelfth Army Group was the river Elbe, where SHAEF had determined they would link up with advancing Soviet troops. Third Army was turned south, into Czechoslovakia and southern Germany. The XIX TAC continued to support the advancing Third Army, right up to May 7, 1945, when hostilities came to an end. The record of the partnership speaks for itself. During 281 days of combat and 74,447 sorties, XIX TAC pilots were credited with 2,340 German planes, 38,541 motor vehicles, 3,888 tanks and armored cars, 3,237 locomotives, 18,437 freight cars, 364 factories, 2,809 gun installations, 1,730 military installations, 285 bridges, and 220 supply dumps.

The XIX TAC losses were 582 aircraft to all causes. Third Army tank destroyers knocked out 648 tanks and 211 self-propelled guns, 349 antitank guns, 175 artillery pieces, 519 machine guns, and 1,556 vehicles.

Third Army antiaircraft fire claimed 1,084 destroyed and 564 probables out of 6,192 German planes that were engaged in Third Army zones. The partnership between the Third Army and the XIX TAC had proven to be one of the most effective in the history of warfare.