By Michael E. Haskew

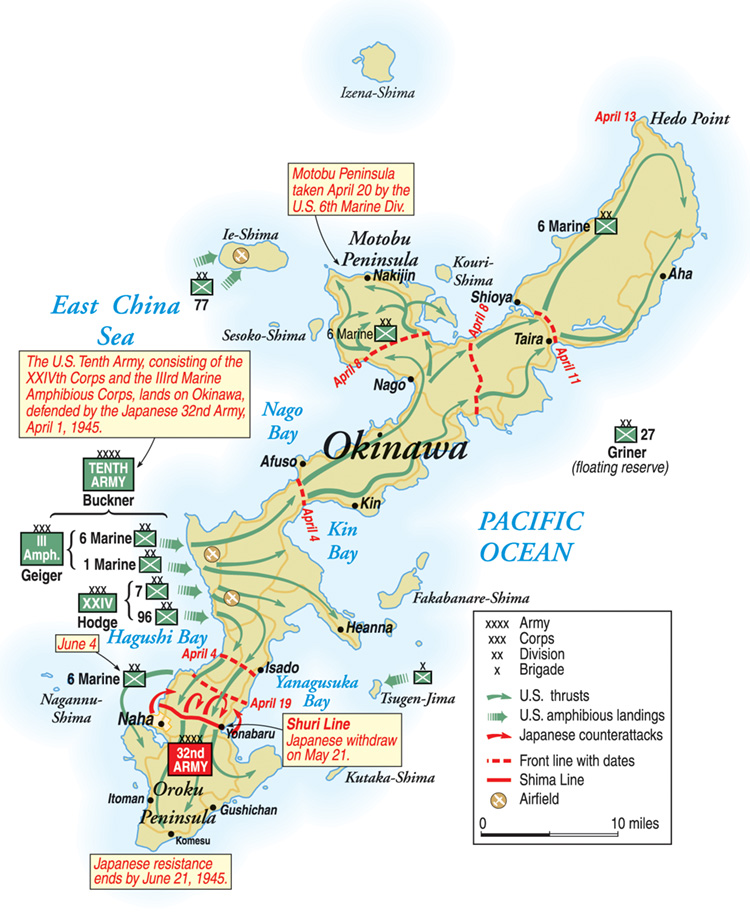

The curious coincidence was obvious to everyone. April 1, 1945, was both Easter Sunday and April Fool’s Day. The immediate gravity of the date was also readily apparent. Designated Love-Day (L-Day) to prevent confusion with the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944, it meant the commencement of Operation Iceberg, the Allied invasion of Okinawa. The preparations for the Okinawa operation were actually larger than those for D-Day, as the U.S. and British Royal navies marshaled 1,300 warships and 750,000 tons of materiel off the island’s coast.

Only 340 miles from the Japanese home island of Kyushu, Okinawa in the Ryukyu archipelago was the last objective of the American military surge across the Pacific during World War II, with the exception of the daunting prospect of an invasion of Japan itself.

By the spring of 1945, senior U.S. commanders respected the tenacity of the Japanese defenders who had opposed their trans-Pacific offensive on land, sea, and air. The cost in lives and treasure thus far had been substantial, but they were resigned to the belief that the bloodletting would continue until American fighting men occupied the Japanese Home Islands. Okinawa was simply another agonizing island fight, the penultimate precursor to the invasion of Japan. Its harbors, airfields, and proximity to Kyushu would facilitate future operations.

At the direction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Chester Nimitz was charged with the seizure of Okinawa, and, as he had done in earlier operations, the Commander in Chief Pacific turned to the familiar team that included Admirals Raymond Spruance, commander of the Fifth Fleet, and Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of the amphibious forces in the Pacific, along with a corps of planners who, after months of on-the-job training, knew their functions in detail.

The looming Operation Iceberg would provide the sternest test of the war for the XXIV Corps of the U.S. Army and the Marines of the III Amphibious Corps, together constituting the U.S. Tenth Army under the unified command of Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, a veteran Army officer and the son of a Confederate general of the American Civil War.

Buckner’s powerful Tenth Army comprised more than 180,000 Marine and Army fighting men, and the commanding general took great pains to be inclusive with his staff structure. He brought 34 Marine staff officers of the Tenth Army to the shores of Okinawa, including Deputy Chief of Staff Brig. Gen. Oliver P. Smith.

The III Amphibious Corps was led by Marine Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, an aviator who had led the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing at Guadalcanal. Under Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge, the XXIV Army Corps included the 7th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions, with the 27th Infantry Division in reserve.

The 1st Marine Division, which had participated in the campaigns on Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu, was commanded by Maj. Gen. Pedro A. del Valle. Formed on Guadalcanal in September 1944, the 6th Marine Division, commander, Maj. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., was the only Marine unit of its size that was formed outside the United States during World War II.

Operation Iceberg included the capture of numerous small islands off the southwest coast of Okinawa prior to the main landings. Kerama Retto and seven surrounding spits of land would serve as a principal supply and refueling point and a safe anchorage for ships damaged while supporting the landings.

Heavy naval bombardment and preliminary air strikes were to soften up the Okinawan defenses. During the week prior to L-Day, Navy guns fired 13,000 rounds of heavy caliber ammunition, and carrier-based aircraft flew 3,095 missions. Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) swam stealthily ashore, checking the depth of the water at various times of day and attaching explosives to mines and beach obstacles to clear the way for the landing craft.

Despite recent experience at Iwo Jima, where the defenders had allowed the beaches to become crowded with men and equipment before opening fire, the Americans expected the beaches to be hotly contested from the beginning.

The L-Day assault plan involved landings on the Hagushi beaches along the southwestern shore of Okinawa. In the north, the Marines of the 6th Division were to land, with the 1st and 2nd Battalions of Colonel Merlin F. Schneider’s 22nd Marines hitting Green Beaches 1 and 2. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of Colonel Alan Shapley’s 4th Marines were to come ashore at Red Beaches 1, 2, and 3. To the south in the 1st Marine Division’s sector, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of Colonel Edward W. Snedeker’s 7th Marines were to land at Blue Beaches 1 and 2, while the 1st and 2nd Battalions of Colonel John H. Griebel’s 5th Marines were to land on Yellow Beaches 1, 2, and 3.

Further south, elements of the Army’s 7th and 96th Divisions, under Generals Archibald V. Arnold and James L. Bradley respectively, were to come ashore on beaches designated Purple, Orange, White, and Brown. Once ashore, the Marines and Army troops were to strike eastward across the Ishikawa Isthmus, capture two key airfields (Yontan and Kadena) to bisect the island, and then turn north and south to secure the length of Okinawa.

While the actual landings were taking place, the 2nd Marine Division was to execute a feint similar to a diversion performed off Tinian in the Marianas the previous year. The complex movement involved loading the Marines aboard landing craft and approaching the Minatoga beaches on Okinawa’s southeast coast simultaneously with the landings at the Hagushi beaches to distract the Japanese before turning away.

American planners were under no illusions and expected heavy casualties. From the senior commanders down to the sailors aboard each ship in the Navy there was concern for the fleet that would be obliged to lie off Okinawa’s shores for an indeterminate period of time. The anxiety arose from the prospect that Japanese suicide aircraft, the dreaded Kamikaze, would assail the fleet in tremendous numbers.

Operation Iceberg lasted 82 agonizing days and yielded an immense harvest of death and destruction. American combat casualties on Okinawa totaled 7,374 killed, 31,807 wounded, and 239 missing. At sea, the U.S. Navy endured the most harrowing chapter in its combat history, with 4,907 killed or missing, 29 ships sunk, and 120 damaged. Twenty-three Medals of Honor were earned on Okinawa, 11 of which were posthumous. When victory was won, the Marine Corps, Army, and Navy justifiably shared in the praise that followed. And despite the inevitable conflict from time to time, Okinawa was a model of inter-service cooperation.

The Japanese garrison, numbering more than 100,000 including Okinawan conscripts, was decimated; only about 11,000 prisoners were taken. The others perished along with more than 1,000 Kamikaze pilots and thousands of sailors who died during the last combat convulsion of the Imperial Navy, many of them aboard the super battleship Yamato. The death toll among Okinawan civilians was staggering—roughly 150,000 men, women, and children.

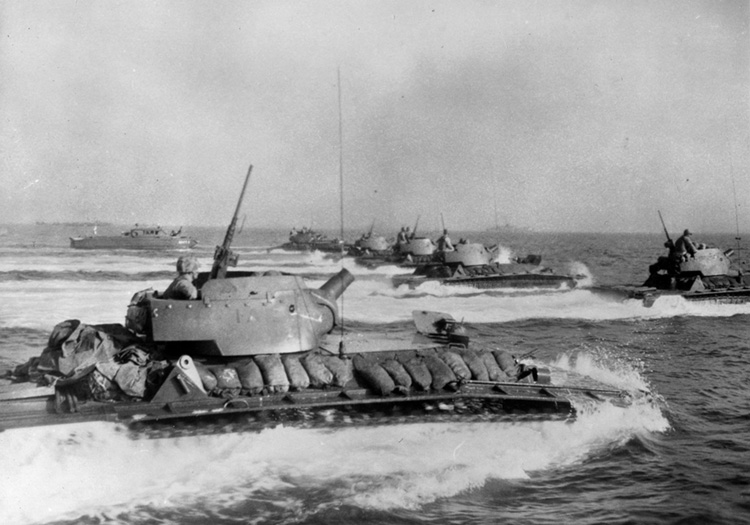

Under a heavy canopy of air cover and shelling, the invasion of Okinawa began on the morning of April 1 with landing-craft engines roaring, churning a virtually unbroken stretch of white wakes eight miles wide. Eerily, resistance was almost nonexistent; American troops flooded the beaches. At the end of the day, 60,000 men were ashore. Only 28 were killed, 104 wounded, and 27 missing. The beachhead was rapidly expanded to 15,000 yards wide and 5,000 yards deep.

Famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote, “Never before had I seen an invasion beach like Okinawa. There wasn’t a dead or wounded man in our whole sector of it. Medical corpsmen were sitting among their sacks of bandages and plasma with nothing to do. There wasn’t a single burning vehicle, nor a single boat lying wrecked on the reef or shoreline. The carnage that is almost inevitable on an invasion was wonderfully and beautifully not there.”

It was the proverbial calm before the storm. From his command post at Shuri Castle, Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, commander of the Japanese 32nd Army, watched the Americans deposit 16,000 combat troops ashore in an hour. The sight was awe inspiring and undoubtedly disconcerting, but it played into his defensive plan.

Ushijima had arrived on Okinawa in August 1944, accepting the burden of leading his command in a fight to the death. He understood the concept of defense in depth. While he would concede the Kadena and Yontan airfields and allow the Americans to establish themselves ashore, he would concentrate his resources in the rugged terrain of southwestern Okinawa, command a ferocious defense, and bleed the enemy white.

Waves of Kamikaze pilots would simultaneously crash their bomb-laden planes into the ships of the Fifth Fleet. The combined effort would buy precious time for Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo to continue feverish preparations for the defense of the home islands.

Ushijima’s forces included three infantry divisions: the veteran 9th, the 24th—well-equipped but inexperienced—and the 62nd. The 44th Independent Mixed Brigade had lost 5,600 of its combat troops on June 29, 1944, when the transport Toyama Maru was torpedoed and sunk by the submarine USS Sturgeon en route to Okinawa. The 44th was later combined with the 15th Independent Mixed Regiment. An array of artillery, mortar, engineer, and naval troops rounded out the sizable Japanese contingent allocated to Okinawa.

While the Americans were fighting their way across the Pacific, becoming accustomed to savage assaults and difficult island campaigning, Ushijima utilized his time well, fortifying the ridges, draws, hills, and ravines of southeastern Okinawa. The high ground was honeycombed with tunnels, bunkers, pillboxes, artillery emplacements, and machine-gun nests with interlocking fields of fire. Some positions were located in the mouths of caves connected by a labyrinth of subterranean passages. The defenders even mounted weapons in the stone tombs of long-deceased Okinawans.

Ushijima’s three defensive lines presented formidable obstacles, and breaching them would prove to be agonizingly slow and costly for the Americans. The first line extended just below the Ishikawa Isthmus from Skyline Ridge in the east to Kakazu Ridge in the west; three weeks of fighting were required to break through it. The second line stretched from Yonabaru near the east coast across Shuri Ridge and Shuri Castle, the ancient abode of the kings who once ruled the Ryukyu Islands, to the port of Naha in the east. Ushijima decided to make his final stand at the third defensive line, strung along an arc of fortified hills that dominated the slope of extreme southern Okinawa to the shores of the East China Sea.

Ushijima’s troops were armed with a large number of heavy weapons, from the proven 47mm anti-tank gun that could penetrate the armor of the American M4 Sherman medium tank, to 150mm howitzers and massive 320mm spigot mortars, which pitched high-arcing shells so huge that the Americans nicknamed them “ashcans.” Ushijima chose to bide his time, allowing the Marines and Army troops to overwhelm the token forces he had committed to northern Okinawa. The death drama would play out in the south.

The ease of the landings brought exhilaration for the American ground troops on Okinawa. Their progress was stunningly swift. In just four days, the invaders captured objectives that senior commanders had expected to require three weeks and hundreds of casualties. By 10:30am on L-Day, the 7th Infantry Division had captured Kadena airfield and continued advancing east and south with the 96th Division on its right. By 1 PM, the 6th Marine Division had taken Yontan airfield. And by dusk on April 3, the 1st Marine Division had crossed the Ishikawa Isthmus and occupied the Katchin Peninsula. Okinawa was swiftly cut in half. The Marines of the 1st and 6th Divisions fanned out to the north and west, with the biggest challenge being the lengthening supply lines as logistics personnel struggled to keep pace with the advance.

Within 72 hours, the two airfields were operational. Marine Air Groups 31 and 33 flew in from escort carriers offshore. Their Vought F4U Corsairs served as interdiction fighters, flying combat air patrols (CAP) above the fleet, and as ground-support aircraft until that responsibility switched to carrier-based Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters. More tactical air power reached Yontan and Kadena within days: Night fighters, torpedo bombers, and observation planes arrived, along with an Army Air Forces fighter wing.

The few Japanese troops detailed to defend central Okinawa were hunted down by 1st Marine Division patrols that subdued pockets of resistance. Meanwhile, the 6th Marine Division raced northward, seizing the village of Nago, the largest town in northern Okinawa, by April 7. In 13 days, the division advanced 55 miles. The 22nd Marines then occupied the thumb-shaped Hedo Misaki Peninsula at the extreme northern tip of the island.

Soon, however, the window of rapid movement began to close. Rising 1,200 feet above sea level near Hedo Misaki, Mount Yae Taki offered extremely favorable defensive ground. Colonel Takesiko Udo and elements of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, known as the Udo Force, occupied prepared defenses in an area of six square miles and made a tough stand. Two Japanese infantry battalions, an artillery company, and an anti-tank company, roughly 2,000 troops, stymied the Marines for five days.

Five battalions of the 4th and 29th Marines attacked Mount Yae Taki repeatedly from east and west, transiting minefields swept by enemy gunfire preregistered to contest the approaches. The 14-inch guns of the battleship USS Tennessee and low-level bombing runs by Corsairs of Marine Fighter Squadron 322 (VMF-322) helped crack the tough nut of Mount Yae Take. The Udo Force was annihilated. The Marines lost 207 killed and 757 wounded before the Motobu Peninsula was cleared on April 20.

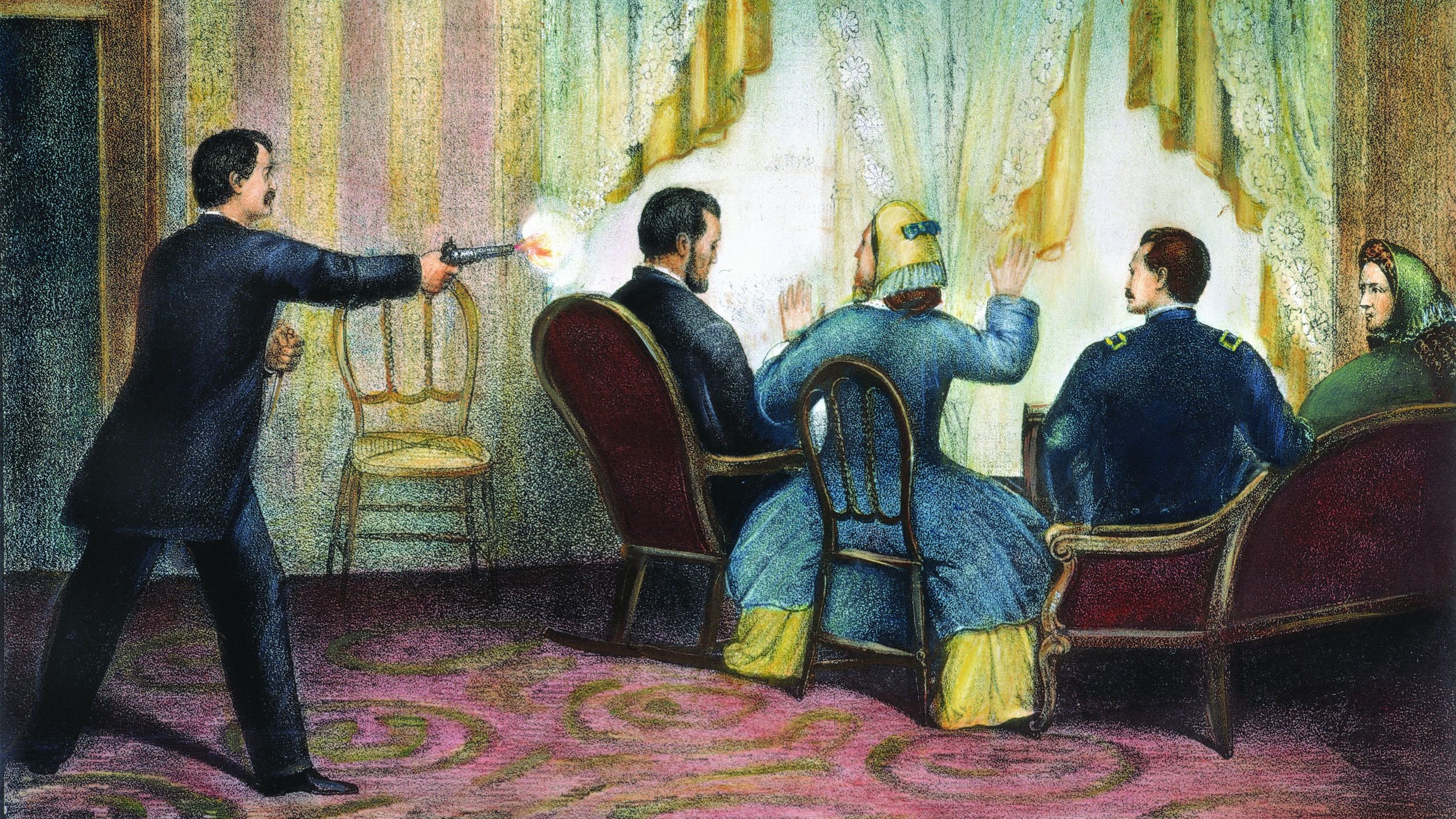

While the brisk northward advance on Okinawa was in progress, the troops received news that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died suddenly on April 12. A Japanese propaganda leaflet crudely attempted to link the president’s death with the ongoing battle for Okinawa. It warned, “…The dreadful loss that led your late leader to death will make you orphans on this island…”

Along with the swift conquest of northern Okinawa, Army and Marine fighting men occupied several small islands nearby. Under the command of Major James L. Jones, the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Force Reconnaissance Battalion executed several landings in advance of Army assaults to seize these islands. On April 16, the Marines took Minna Shima, hauling ashore a battery of 105mm howitzers to support the 77th Infantry Division assault on Ie Shima, only 6,000 yards away.

The immediate objective of the Ie Shima landing was the capture of its airfield, but the 77th Infantry Division confronted 5,000 defenders. After six days of fighting, Ie Shima was secured, but the 77th Division sustained 1,100 casualties.

Correspondent Ernie Pyle was one of those killed, fatally wounded in the head by Japanese machine-gun fire. Pyle’s eloquent and sometimes heart-wrenching dispatches from combat zones in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific had brought the experience of the common fighting man home to millions of Americans. After the battle, the soldiers of the 77th Division erected a monument to Pyle on Ie Shima. It read simply that the soldiers had lost “a buddy.”

The Army troops of the 7th and 96th Divisions were the first to probe Ushijima’s prepared defensive lines in southern Okinawa. General Buckner came ashore on April 14 and soon committed the reserve 27th Infantry Division to the effort to breach Ushijima’s first line. A major attack was launched on April 19, but initial gains could not be held, and the attack was repulsed. Advancing Sherman tanks near Kakazu became separated from their infantry support, and Japanese anti-tank guns destroyed or disabled 22 of the 30 Shermans committed to the attack.

With offensive momentum slowed, Buckner rejected a suggestion from General Andrew Bruce, commander of the 77th Infantry Division, that a second amphibious landing could be mounted on the beaches of southern Okinawa to outflank the Japanese. Buckner considered the operation too risky and the beaches unfavorable landing sites due to high cliffs, while it would also stretch a supply effort that was already under duress. Buckner chose instead to bludgeon his way directly through the stout defenses.

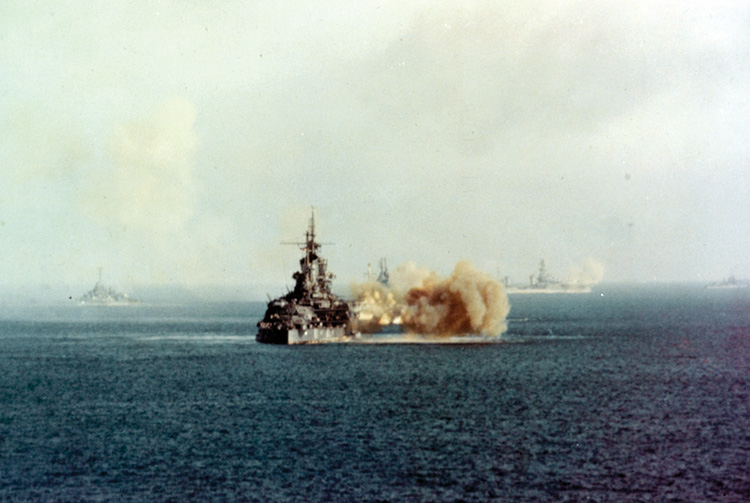

On April 23, Admiral Nimitz arrived at Yontan airfield, toured the occupied territory on Okinawa, and met with Buckner to urge a redoubling of the offensive effort. Nimitz was worried about the Fifth Fleet offshore, as the savage Kamikaze attacks were taking a fearful toll. He admonished Buckner to crank the offensive into high gear within five days. Otherwise, he rasped, “We’ll get someone here to move it…I’m losing a ship and a half each day out here. You’ve got to get this thing moving.”

General Alexander A. Vandegrift, the victor at Guadalcanal and current Commandant of the Marine Corps, was a member of Nimitz’s entourage. Like General Bruce, Vandegrift raised the prospect of a second amphibious assault, offering the 2nd Marine Division for the job. He explained that the division could depart Saipan within six hours. Again, Buckner declined.

Nimitz was uncharacteristically forceful in his demand of Buckner, and his concerns were well-founded. While fighting raged on Okinawa, the surrounding waters of the Pacific Ocean and the East China Sea were roiling in the throes of Operation Ten Go, the gigantic series of Kamikaze onslaughts that called for as many as 4,500 aircraft to be hurled against the American ships.

Ten Go, or Heavenly Operation, included 10 massed Kamikaze sorties, known as Kikusui, or Floating Chrysanthemums, and each Kikusui might include more than 350 planes, virtually anything in the Japanese arsenal that could fly. One of the most terrifying aerial weapons was a flying bomb called the Ohka, or Cherry Blossom, packed with more than 2,600 pounds of explosives. A forerunner of the modern cruise missile, the Ohka was slung beneath a bomber, carried within range of the American fleet, and jettisoned. The pilot then engaged three solid-fuel rockets and streaked toward his target at 650 miles per hour. The Americans nicknamed the flying bomb “Baka,” Japanese for “Fool.”

The relentless strain on the American sailors took its toll, both physically and psychologically. Moments after a particularly vicious Kamikaze attack, one sailor stood up at his shipboard gun mount, declared, “It’s hot today!” and jumped over the side, never to be seen again.

The Fifth Fleet remained on station, suffering terribly. When a pair of Kamikazes struck the USS Bunker Hill on May 11, the aircraft carrier had been in the combat zone for 58 days.

Army, Navy, and Marine pilots defended the fleet with tremendous valor and devotion to duty. During an engagement on April 22, for example, three Marine Corsairs of VMF-323 shot down 16 enemy planes in just 20 minutes. Squadron commander Major George C. Axtell accounted for five of these.

Still, the Kamikazes were relentless. Inevitably, some suicide pilots managed to get through the curtain of CAP fighters and antiaircraft fire. However, during one of the U.S. Navy’s finest hours, the Fifth Fleet, which was redesignated the Third Fleet when Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey relieved Admiral Spruance on May 27, became known as “the fleet that came to stay.”

The gains made by the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions and the grind of sustained combat prompted Ushijima to withdraw from his first line of defense under the cover of thick fog and an artillery barrage. The Japanese withdrawal was accomplished hours after Admiral Nimitz had departed Okinawa. The 27th Infantry Division took the lead in the effort to clear the Japanese rear guard from the rough terrain between the forward fortifications and the Shuri Line.

In early May, General Buckner ordered the 1st Marine Division to relieve the battered 27th Infantry Division on the right, and soon the 6th Marine Division was ordered to come up on the far right flank near the sea. General del Valle took charge in the western area on May 1, and the 77th Infantry Division redeployed from Ie Shima, taking over for the 96th Division in the center.

The 96th Division was ordered to rest for 10 days and then relieve the bloodied and fatigued 7th Infantry Division in the east. With these moves, the Tenth Army front stood four divisions abreast, ready to assault the Shuri Line defenses along a compact front extending only about 9,000 yards from east to west.

General del Valle ordered the 1st Marine Division to attack the Awacha Pocket on the morning of May 2. Moving forward in a steady rain, the 5th Marines captured high ground to their front but came under immediate fire from Japanese gunners to their left in the zone of the 77th Infantry Division. The high ground was a warren of draws and ravines that naturally channeled attacking Marines into deadly killing zones, and the day’s progress was disappointing.

That night, the Marines spent exhausting hours fending off Japanese infiltrators, often fighting hand-to-hand. Unrelenting rain hampered the renewal of the attack on May 3, and it took another week of hard fighting to clear the Awacha Pocket.

Just as Buckner’s realignment maneuvers were being completed, the Japanese briefly assumed the offensive. Ushijima was an approachable commander and valued the perspectives of his staff officers. He often allowed them to speak freely, and on the evening of May 2, the conversation became heated during a war council at his headquarters in Shuri Castle.

The 51-year-old Chief of Staff of the 32nd Army, Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho, was a nationalistic zealot. He had been involved in a conspiracy to establish a military dictatorship in Japan as early as 1931 and was actually a war criminal, having issued a shocking order to execute prisoners during the infamous Rape of Nanking in 1937. Cho refused to accept the concept of a defense in depth. He demanded a swift counterattack to throw back the Americans.

Countering Cho’s position was 42-year-old Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, the 32nd Army senior staff officer responsible for planning. Yahara believed that a counterattack would include a suicidal banzai charge, resulting in high casualties and only weakening the Japanese defenses. He offered, “The army must continue its current operations, calmly recognizing its final destiny. Annihilation is inevitable no matter what is done.”

Ushijima and every other staff officer present sided with Cho. The counterattack was set for the night of May 3, with a two-pronged amphibious assault and the main thrust overland. The attack would be supported by artillery, exposing the guns to American counter-battery fire, their bombardment beginning at 10pm and ceasing at 4:30am on May 4. The 26th Shipping Engineer Regiment was one of the leading units in the counterattack, boarding barges and heading toward the beaches on the east coast of Okinawa near Skyline Ridge to the rear of the forward American positions.

Minutes after the Japanese troops shoved off, U.S. Navy warships began to shadow them. The patrolling craft then pounced with fury, blasting many of the barges to bits. Those Japanese troops that reached the shore were mowed down by concentrated fire from forward positions of the 7th Infantry Division and annihilated.

The second amphibious landing occurred at Kusan, on Okinawa’s west coast, where the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines and the LVT-As of the 3rd Armored Amphibian Battalion shredded 700 Japanese troops with rifles, machine guns, and 75mm artillery. The 1st Reconnaissance Company and a War Dog platoon killed another 75, hunting down the last 65 holdouts by daybreak.

On the morning of May 4, Ushijima ordered two battalions of the 24th Division to begin the land phase of the counterattack at 5am; however, these troops failed to reach their start line at the scheduled time and were caught in the open. American artillery and mortar fire slashed through their ranks. Then, after dark on the 4th, the last of the abortive Japanese thrusts began. Two infantry battalions assaulted 7th Division positions around the Tanaburu escarpment. Some slight penetrations were gained, but these were isolated and destroyed throughout the next day. Only a few Japanese survivors returned to their lines as darkness fell on May 5.

The Japanese 32nd Army lost 6,000 troops and 59 precious artillery pieces during the disastrous counterattack. When an enraged group of junior officers drew their swords, surrounding Cho and demanding an explanation for the debacle, he was unable to speak. The only senior Japanese officer to survive the battle for Okinawa, Colonel Yahara later described the devastated assaults as “the decisive action of the campaign.” On the mournful night of May 5, a tearful Ushijima summoned Yahara to his private quarters, apologized profusely, and swore that he would never again disregard the colonel’s advice.

When the Tenth Army realignment was completed during the first week of May, the 1st Marine Division had already taken 1,400 casualties in six days of fighting north of the Shuri Line. On May 7, Private Dale M. Hansen of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, earned the Medal of Honor when he destroyed a Japanese pillbox, picked up a rifle to replace his own that had been shattered, and dashed to the crest of a nearby ridge. Six enemy soldiers confronted Hansen, and he shot four of them dead before his rifle jammed. The other two Japanese soldiers jumped him, but Hansen fought them off with the rifle’s butt and scrambled for cover.

Re-armed with yet another rifle and a few grenades, Hansen, a 22-year-old farmboy from Nebraska, went after the enemy again, killing eight more and destroying a heavy mortar position. His one-man assault jolted the Marines to action, claiming an entire embattled ridgeline. Hansen was killed by a Japanese sniper four days later, and his parents accepted his posthumous Medal of Honor during ceremonies in 1946.

In early May, the 22nd Marines relieved the 7th Marines as the 6th Marine Division anchored its right flank against the East China Sea on the far right of the Tenth Army line. On May 9, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines attacked Hill 60. Its commander, Lt. Col. James C. Murray, Jr., was wounded by a sniper. During the night, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines fought hand-to-hand with scores of Japanese infiltrators.

On May 11, Buckner ordered a general attack along the length of the Shuri Line. With Nimitz’s words still ringing in his ears, Buckner was doing his best to speed the battle along, but the Japanese had apparently fortified every cave and crevice on Okinawa. Progress was painfully slow.

“We will take our time and kill the Japanese gradually,” a determined Buckner barked to a group of reporters who had gathered around. Although progress was virtual nonexistent at times, the killing went on without respite.

After two days of difficult combat, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 7th Marines took Dakeshi Ridge. The battle was reminiscent of the terrible fighting in the Umurbrogol on Peleliu; each battalion commander in the 7th Marines was a veteran of that bloody engagement. The U-shaped ridge was studded with machine-gun and mortar emplacements. The Japanese often fired from the reverse slopes, using the cover of the crest as protection from Marine return fire.

The 1st Battalion reached the top of Dakeshi Ridge at two points on May 11 but fell back under a hail of Japanese shells. One Marine remembered, “We did damned little attacking. Every time a man raised his head he was hit.” The next morning, three Sherman tanks—one armed with a 75mm cannon and the others with flamethrowers—began creeping their way up the slope. The .30- and .50-cal. machine guns aboard the tanks chattered, and the flamethrowers spewed streams of jellied gasoline. The 2nd Battalion riflemen followed closely behind, shooting enemy soldiers that broke under the strain and ran along the reverse slope.

Ushijima realized that Dakeshi Ridge had fallen in the coordinated assault due to the firepower of the armored vehicles. He acknowledged, “The enemy’s power lies in his tanks. It has become obvious that our battle against the Americans is a battle against their tanks.” The Marine and Army armored units took heavy losses on Okinawa, but they were instrumental in dealing with enemy strongpoints and achieving the eventual victory.

Dakeshi Ridge was only the first of many fortified positions that studded the Shuri Line north of Ushijima’s headquarters. The high ground of Wana Ridge and craggy Wana Draw lay beyond, stretching southward from Dakeshi Ridge. Wana Draw was a labyrinth of caves, rocky outcroppings, and high cliffs; the troops of the Japanese 62nd Infantry Division were well entrenched in defense. Beginning on May 12, the 1st Marine Division assaulted Wana Ridge and Wana Draw for nearly three weeks in the most difficult 1,200-yard advance the “Old Breed” encountered during the entire Pacific War.

During earlier operations, the troops and tanks of the 1st Marine Division had perfected the cooperative combat tactics of infantry and armor. Tanks blasted away with their 75mm guns and belched flame, while riflemen sheltered in the cover of their armor and dispatched any Japanese soldiers that ventured forward with satchel charges strapped to their bodies, willing to commit suicide by throwing themselves against the 33-ton Shermans.

During a single day of fighting on May 16, Marine Shermans and Army flamethrower tanks attached to the 1st Marine Division effort fired 5,000 75mm shells and 175,000 rounds of .30-cal. ammunition while expending 600 gallons of searing napalm at Japanese strongpoints. On May 17, tanks working with the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines took fire from twin 47mm anti-tank guns. Map coordinates were relayed to the battleship USS Colorado, and its heavy 16-inch guns destroyed the enemy weapons with a well-placed salvo.

The combat in Wana Draw was so desperate that the 7th Marines lost 500 men in five days after the regiment had suffered 700 casualties in the battle at Dakeshi Ridge. In three days, from May 16-19, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines also lost a dozen officers.

Wana Draw was 400 yards wide, spreading southward from Wana Ridge. It narrowed precipitously in its approach to Shuri Ridge and the town of Shuri. Marines were naturally funneled into killing zones covered by interlocking fields of machine-gun fire and preregistered mortars, which the Japanese had entrenched in concealed emplacements.

After absorbing 500 replacements, the 1st Marines stepped up their attacks on May 20, relieving the exhausted 7th Marines. Meanwhile, the 5th Marines claimed Hill 55 on the western approaches to Wana Draw, finally knocking out several Japanese guns that had harassed the Americans for days.

Through 19 days of horrific combat, progress was measured in yards and in the number of casualties taken. The Marines lost an average of 200 dead and wounded for every 100 yards gained. Much of the fighting took place in steady, sometimes torrential rain, compounding the misery. By the end of May, the 1st Marine Division had ground to a halt on a single ridgeline short of Shuri.

On the morning of May 10, the 6th Marine Division prepared to move forward, crossing the Asa River near the western coast of Okinawa on a Baily bridge thrown across by Marine engineers. During the next 36 hours, the Marines advanced roughly 1,000 yards. Early on May 12, they had drawn up before a small hill rising sharply about 230 feet above them. Surveying their surroundings, the Marines quickly settled on a nickname for this high ground, Sugar Loaf.

Otherwise unimpressive, Sugar Loaf was flanked to the southeast and southwest by two more small hills. These were soon named Half Moon and Horseshoe. One Marine described Sugar Loaf as “a pimple of a hill.” It was obvious to every Marine in the vicinity, particularly the riflemen of the 22nd Marines, that the Japanese would defend these mutually supporting positions tenaciously.

Nevertheless, the Marines did not immediately realize that the complex of small hills was the western command and control hub of the Shuri Line. Japanese troops on Sugar Loaf maintained vigil at the northern apex, and 2,000 Japanese soldiers of the 15th Independent Mixed Regiment, under Colonel Seiko Mita, were ordered to prevent an American breakthrough between the towns of Shuri and Naha. Three thousand more Japanese troops defended Half Moon and Horseshoe.

The agonizing 10-day battle for Sugar Loaf, Half Moon, and Horseshoe was a bloody affair of attrition, and the ordeal of Captain Owen G. Stebbins’ Company G, 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines was indicative of the struggle. Stebbins led a combined assault of infantry and tanks against Sugar Loaf. In a matter of minutes, two of his three platoons were pinned down by machine-gun and anti-tank fire. Stebbins and his executive officer, Lieutenant Dale W. Bair, charged forward, leading the third platoon into a firestorm. Forty men dashed ahead, and 28 were killed or wounded covering the initial 100 yards. Machine-gun bullets slammed into both of Stebbins’ legs.

A Japanese bullet wounded Bair in the left arm. It flopped uselessly against his side. Maintaining his focus, the lieutenant scraped together 25 Marines, some of them wounded, and charged back to the top of Sugar Loaf. A handful of Marines ran the gauntlet to the crest, but they could not hold. Bair ordered the survivors to fall back, dragging wounded men to safety as they were able. At dusk, smoke billowed from the charred hulks of three Sherman tanks. Only 75 of the original 200 Marines in Company G were unhurt, and five assaults had failed to seize Sugar Loaf.

Elements of the 29th Marines were committed to the fight as the carnage continued into the evening of May 14. The two depleted companies of the 22nd Marines remained in the line, contributing as they could. Forty-four Marines were marooned on the slope of Sugar Loaf, pinned down with more than 100 of their original number lying dead or wounded around them.

Major Henry A. Courtney, Jr., executive officer of the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines, concluded that his command could not defend its position indefinitely. He roused the riflemen of Companies F and G to action. Withdrawal, he concluded, would expose them further to murderous fire. The best option was to attack.

“Men, if we don’t take the top of this hill tonight, the Japs will be down here to drive us away in the morning,” Courtney bellowed. “When we go up there, some of us are never going to come down again. You all know what hell it is on the top, but that hill’s got to be taken, and we’re going to do it. I’m going up to the top of Sugar Loaf Hill. Who’s coming along?”

To a man, the 44 Marines rose to Courtney’s call for volunteers. The courageous officer led his men to the crest of Sugar Loaf, and the Marines held until after dark, when incessant mortar and small-arms fire had taken a fearful toll. Fifteen surviving Marines filtered back down the hill as daylight approached. Courtney suffered a fatal wound when a mortar fragment slashed into his neck. He received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Among the intrepid Marines who followed Courtney were the seven riflemen of Corporal James L. Day’s squad from Company F, 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines. Five squad members were quickly lost to enemy fire, while Day and Pfc. Dale Bertoli became isolated on the western slope of Sugar Loaf. During a harrowing four-day, three-night ordeal, Day and Bertoli tossed grenades and emptied clips from their M1s into clusters of Japanese soldiers attempting to fight off successive Marine assaults against the little hill. Finally, the two were ordered to withdraw on May 17. Bertoli was killed a few days later, and Day was wounded. Forty years after the battle, Maj. Gen. James L. Day returned to Okinawa to take command of Marine installations on the island.

In three days of intense combat, the 22nd Marines lost 400 killed and wounded—nearly 50 percent casualties. A Japanese artillery shell hit the command post of the 1st Battalion, 22nd Marines on May 15, killing Major Thomas Myers, the battalion commander, and wounding the commander and executive officer of the tank company supporting the attacks on Sugar Loaf. In response, General Shepherd warned other officers not to expose themselves to enemy fire. It was, however, an impractical admonition. The officers were compelled to lead from the front and face the real prospect of becoming casualties.

On May 16, the 29th Marines took the lead in the attacks against the potent defenses of the Sugar Loaf-Horseshoe-Half Moon complex. Company E, 2nd Battalion, 29th Marines charged Sugar Loaf four times the next day and lost 160 men while inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. These Marines held the summit of Sugar Loaf for several hours before withdrawing after dark.

Company D, 2nd Battalion, 29th Marines took up the effort on May 18 as Captain Howard L. Mabie, the company commander, led the attack on Sugar Loaf while the Japanese defenders on Half Moon and Horseshoe were blanketed with a barrage of heavy suppressing fire from other units of the 29th Marines. Supporting tanks circled around both flanks of Sugar Loaf, rumbled south through minefields in the valley that had been so difficult to traverse, and raked the Japanese troops who emerged from their hiding places on the reverse slope of Sugar Loaf. Company D held Sugar Loaf through the night and never relinquished the crest.

General Shepherd ordered the 4th Marines into the line to relieve the 29th, and by late afternoon on May 20, its 1st and 3rd Battalions had made substantial gains on both flanks of the 6th Division front. The 3rd Battalion occupied most of Horseshoe, and the 2nd Battalion captured the bulk of Half Moon.

Gunnery Sergeant Mike Goracoff of the 4th Marines assessed the long battle for Sugar Loaf and the surrounding area: “We made 11 thrusts at that hill and fell back each time with most of our boys dead or missing. It wasn’t uncommon to see a Pfc. commanding the platoon as it fell back from a push at the hill. It seemed that the lieutenants fell first, then the sergeants.”

The bloody fight for Sugar Loaf had left the 6th Marine Division with nearly 2,700 killed and wounded. Another 1,300 Marines were lost due to combat fatigue, a common phenomenon amid such dreadful carnage. While the Marines continued fighting in western Okinawa, the 96th Infantry Division captured Conical Hill and the 7th Infantry Division took Yonabaru. Both Japanese flanks were endangered, and Ushijima decided reluctantly to abandon his positions at Shuri Ridge and Shuri Castle. Colonel Yahara advised a withdrawal to the third and final defensive line across the Kiyamu Peninsula. Ushijima issued the order, taking advantage of the concealment offered by foul weather. Under steady rain and cloaking fog, the Japanese fell back under the Americans’ noses without attracting more than casual curiosity.

The rain, torrential at times, slowed the ensuing American advance, turning roads into seas of mud and making the going tough for even tracked vehicles. Still, 6th Marine Division tanks clattered toward the outskirts of Naha and probed into the village on May 28. Marine patrols encountered only light resistance, and by the next morning, Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, under Captain Julian D. Dusenbury, advanced to attack Shuri Ridge. Expecting a fight, the Marines reached the crest virtually without firing a shot.

The surprising success of Company A led Marine officers to conclude that Shuri Castle lay tantalizingly close. However, the long-sought prize was in the zone of operations of the Army’s neighboring 77th Infantry Division. Nevertheless, the opportunity to seize the objective was at hand. General del Valle weighed the decision and concluded that antagonizing his Army counterpart, General Bruce, was worth risking in return for the swift capture of Shuri Castle.

Company A crossed quickly into the 77th Division zone and claimed Shuri Castle just after 10am. Dusenbury was from South Carolina and ordered a Confederate flag that he carried in his helmet liner run up the nearest pole. The senior commanders at Tenth Army headquarters were perturbed when they spotted the Stars and Bars flying above Shuri Castle; two days later, the Stars and Stripes was raised in its place. Marines of the 1st Division had raised the same flag on Peleliu months earlier.

General del Valle actually reached out to the 77th Division commander and the rest of his Army command cadre in an attempt to smooth over this most contentious instance of inter-service rivalry during the fight for Okinawa. “I don’t think a single Army division commander would talk to me after that,” he remembered. Still, the hard feelings took a back seat to the business at hand.

About eight square miles of southern Okinawa still belonged to the Japanese. Despite heavy American shelling and air attacks, the remnants of the 32nd Army remained defiant. The Japanese front stretched four miles across Kunishi Ridge in the west to Hill 89, where Ushijima’s final command post was established, and then to Hill 95 on the east coast.

For several days General Buckner remained unconvinced that the Japanese were withdrawing from the Shuri Line, but when he realized that there was another enemy defensive line to be reduced, he once again realigned the Tenth Army front. From west to east, the 1st Marine Division, 96th Infantry Division, and 7th Infantry Division would continue to fight and die, advancing slowly. The slog southward began again in heavy rain.

The 6th Marine Division was tasked with taking Naha airfield, requiring control of the Oroku Peninsula as a prerequisite. Rather than a protracted overland assault, General Shepherd requested permission for an amphibious landing across the Kokuba estuary to hit the Japanese flank. After scraping together enough operational LVTs during a narrow 36-hour window to plan and execute the maneuver, Colonel Shapley’s 4th Marines came ashore on the Oroku Peninsula early on June 4. Elements of the 29th Marines followed, while the 22nd Marines hammered the enemy from the landward side.

Amid nine more days of fighting, the Marines took on roughly 5,000 Japanese troops willing to die for the emperor under the command of Rear Admiral Minoru Ota, one of the few senior officers of the once-powerful Special Naval Landing Force left alive. Ota’s ad hoc force fought desperately from the cave entrances, the hulks of wrecked planes at the edge of Naha airfield, and machine-gun nests. When the Marines prevailed, only 200 surrendered.

Ota’s last message to Imperial Navy headquarters was resolute, and then he committed suicide along with his staff officers. “The troops under my command have fought gallantly, in the finest tradition of the Japanese Navy,” he wrote. “Fierce bombardment may deform the mountains of Okinawa but cannot alter the loyal spirit of our men.”

The Marines lost 1,608 killed and wounded during the capture of the Oroku Peninsula and Naha airfield.

The 7th Infantry Division’s 32nd Regiment and supporting Sherman tanks seized Hill 95 on June 12. That same day, the 17th Regiment occupied the eastern end of the Yuza Dake escarpment, unhinging the right flank of Ushijima’s defensive line. In the center, the 96th Division claimed the rest of the Yuza Dake by dusk on the 13th.

Coordinating with the Army attacks, the 1st Marine Division assaulted the western anchor of the Japanese line. With Colonel Snedeker’s 7th Marines leading the way, the attack’s objective was Kunishi Ridge. The prelude to that assault concluded when Hill 69 fell to the 2nd Battalion on June 10. Kunishi Ridge itself lay across open fields and rice paddies; it rose to a more imposing height than the stubborn Sugar Loaf. Although it lacked the concentrated covering firepower of the Sugar Loaf-Horseshoe-Half Moon complex, Japanese artillery, mortars, and machine guns were trained on the approaches from neighboring high ground.

The 7th Marines stepped off against Kunishi Ridge on June 11, and the initial assaults were repulsed with heavy losses. Snedeker ordered a night attack, and by 5am on the 12th, two Marine companies were on the crest. They wiped out surprised Japanese troops who were cooking breakfast. Soon enough, the Japanese responded, mounting heavy counterattacks against the two Marine companies. Three attempts to reinforce the Marines atop Kunishi Ridge were turned away.

Finally, Snedeker sent nine Sherman tanks across the valley, each of them loaded with six Marine riflemen. Once atop Kunishi Ridge, each tank disgorged its cargo through the hatch in the bottom of its hull. Twenty-two wounded men were then loaded aboard the tanks and evacuated.

By the time the 7th Marines were relieved on June 18, the 1st Tank Battalion had evacuated 1,150 wounded men while bringing 90 tons of supplies and 550 reinforcing riflemen up the embattled slope. In five days of fighting, the last heavily defended ridgeline on Okinawa was captured.

As the Marine reinforcements went into the line on the 18th, General Buckner climbed the high ground of Mezado Ridge to observe the deployment. Japanese artillery spotters watched the cluster of officers gathered in an exposed position, and guns on a nearby ridge opened fire. Five shells slammed into the ground near Buckner’s party, fracturing coral formations in a shower of rock shards and shrapnel. Buckner was hit in the chest by a splinter roughly the size of a dime. He died 10 minutes later, one of the highest-ranking American military officers killed in action in World War II.

General Geiger took temporary command of the Tenth Army after Buckner’s death, and with the fall of Kunishi Ridge, only a few pockets of resistance remained. Five days later, Army General Joseph Stilwell arrived to take command of Tenth Army.

On June 22, General Geiger at long last declared Okinawa secure. That same day, while the soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division swarmed above the entrance to his headquarters cave on Hill 89, General Ushijima committed ritual suicide alongside General Cho. Before he died, Cho scribbled on a slip of paper, “Our strategy, tactics, and techniques were all used to the utmost. We fought valiantly, but it was as nothing before the material strength of the enemy.”

Ushijima ordered Yahara to surrender to the Americans, making himself a prisoner of war. “If you die there will be no one left who knows the truth about the battle of Okinawa,” he told the loyal colonel. “Bear the temporary shame, but endure it. This is an order from your Army commander.”

Operation Iceberg, the climactic engagement of World War II in the Pacific, ended after nearly three months of harrowing combat. Up to that time, death and suffering on such a scale had seemed impossible.