By Mason B. Webb

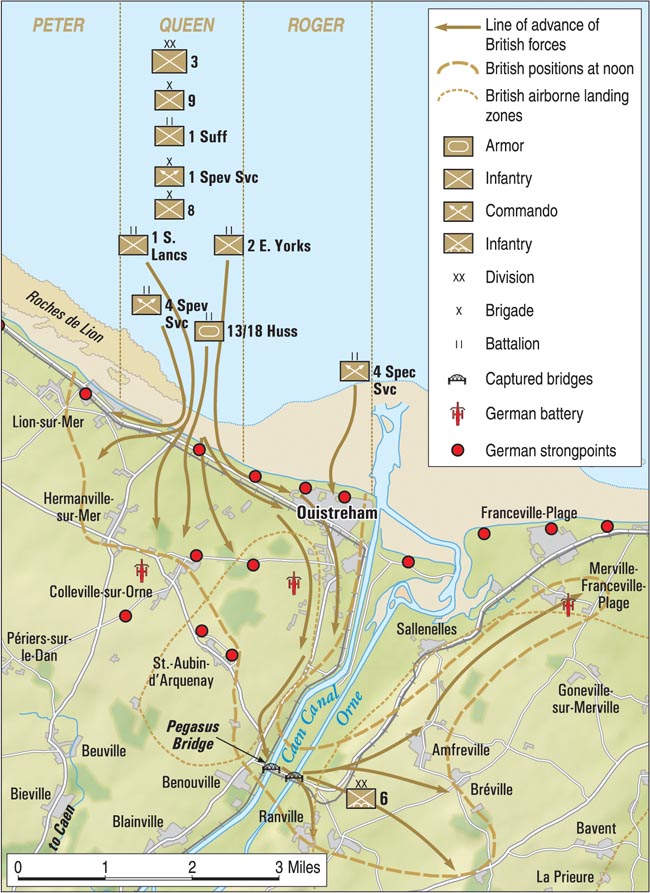

The easternmost Allied landing beach of the Normandy invasion of June 6, 1944, was code-named Sword. It was the responsibility of British Maj. Gen. Thomas Gordon Rennie’s 3rd Infantry Division, part of Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army and augmented by several special units that brought the total number of men who landed at Sword by nightfall up to 29,000.

Rennie’s mission was to establish a bridgehead between Ouistreham and Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer. Once that was done, the 3rd would drive inland to be in position, along with the rest of the British, Canadian, and French forces landing at adjacent Gold and Juno Beaches, to take the city of Caen, 10 miles south of the coast.

Sword was divided into four sectors labeled (from west to east) Oboe, Peter, Queen, and Roger. It was approximately six miles in width, a mile wider than Omaha Beach in the American sector.

No one knew how the German defenders would react. Informants had told the Allies that one division—the 716th Infantry Division—was stationed in the area, and it was known through spies and aerial reconnaissance that there were numerous fortified bunkers and other fighting positions.

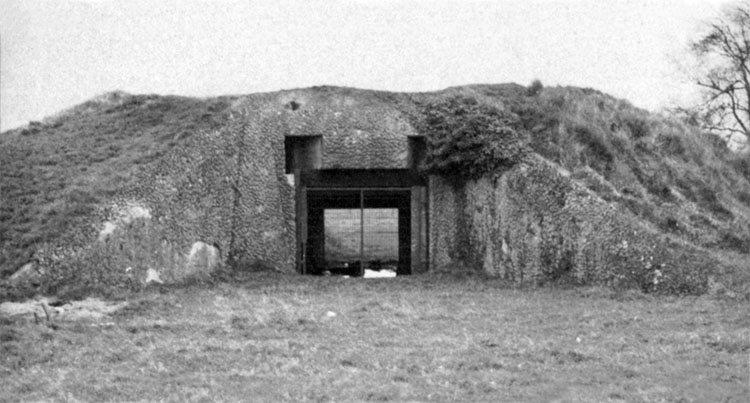

One position in particular was worrisome: a four-gun battery at Merville, on the very eastern edge of Sword Beach across the Orne River from Ouistreham. The caliber of the guns was unknown, but the best guess was that they were 155mm with a range of 10.5 miles, powerful enough to do serious damage to seaborne troops coming ashore.

The task of putting this battery out of commission through the use of both a parachute drop and a glider landing had fallen to Lt. Col. Terence Otway and his 9th Parachute Battalion. Aerial photos revealed that encircling the battery were a 20mm antiaircraft gun, several bunkers, fighting trenches, and a partially completed antitank ditch. The position was surrounded by a cattle fence enclosing a minefield with a depth of 100 yards, the inner border of which consisted of a barbed-wire fence 15 feet thick and five feet high. In places, this inner fence was doubled, and within it, the battery position itself was intersected by cross wire.

Everyone at SHAEF was convinced that the Germans would not have poured so much concrete and so heavily defended the battery if what it housed was insignificant, and so it was added to the list of primary objectives. Since it was believed that the casemates of the battery were immune to aerial assault, SHAEF realized that only a ground assault by a large number of troops could neutralize it. Thus was Otway’s battalion selected and trained for the event.

A few miles farther south of the coast west of Ranville, two vital bridges spanned the Orne River and the parallel Orne Canal. Both of them would need to be captured by a small glider force and held long enough for the amphibious troops to fight their way to them.

Chosen for this task was Major John Howard and his D Company, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Infantry (Ox and Bucks), who would rush in silently in gliders, land close to their target bridges, and overwhelm the Germans guarding them. It seemed a preposterously dangerous thing to do, and the odds of success seemed preposterously small. Nonetheless, Howard and his men, like Otway’s, set about training to accomplish just that.

Comprising the amphibious force of Rennie’s 3rd Division were three infantry brigades: the 8th, 9th, and 185th Infantry, plus the attached 29th Armored Brigade and the 1st and 4th Special Service (Commando) Brigades. Attached to No. 4 Commando was Captain Philippe Kieffer’s 177-man Free French Commando troop.

All was as ready as it could be. Two years of exacting planning had gone into this moment. If any part of the invasion plan failed, then the Allied invasion of the Continent was in jeopardy. No one knew if there would ever be a second chance to plunge the dagger into the heart of Hitler’s Third Reich.

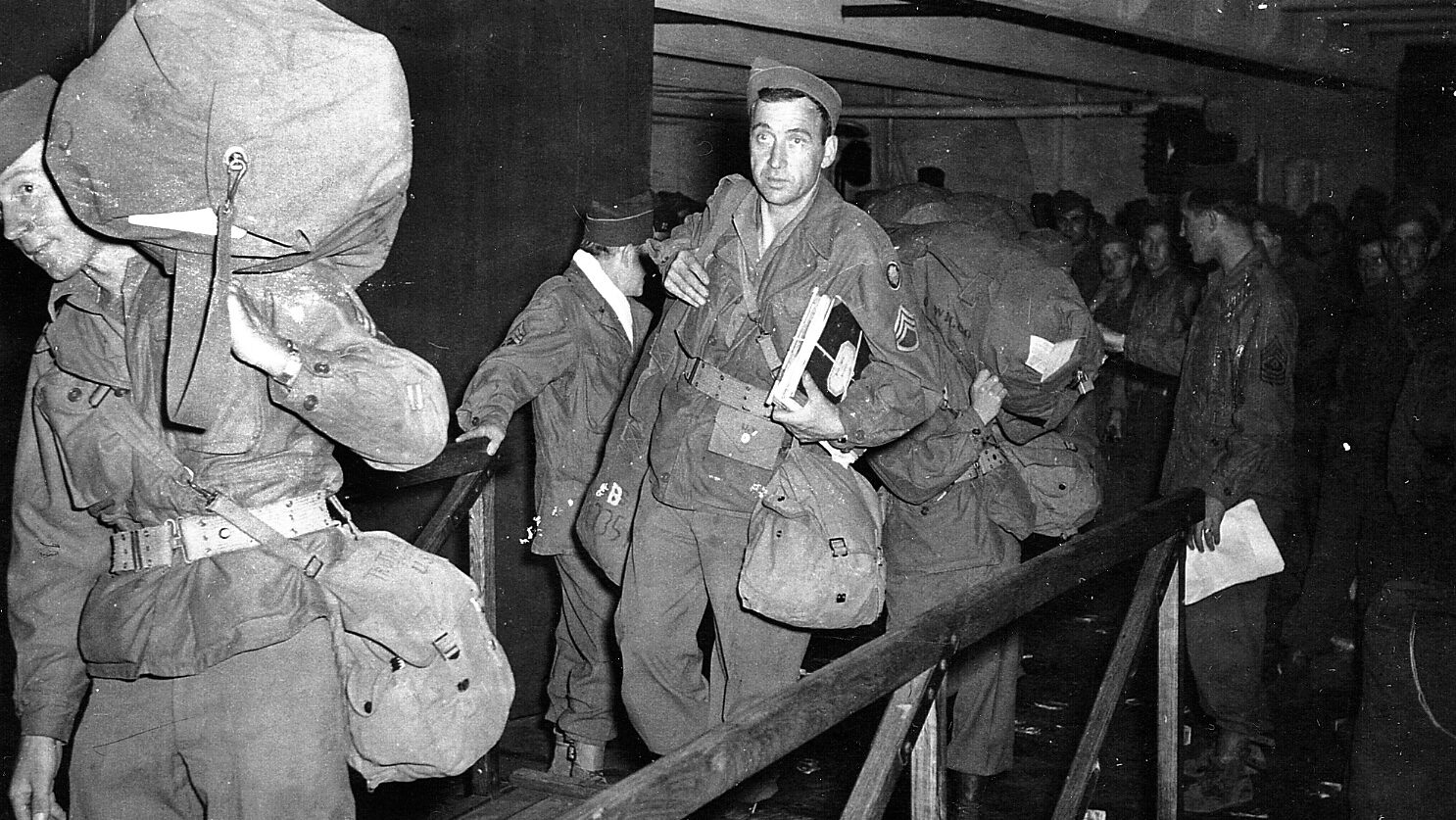

At 3 am on June 6 (the invasion had been postponed for 24 hours because of a strong storm raging through the English Channel), the invasion at Sword Beach was heralded by a shelling and bombardment of German positions by Allied naval and air forces. This was followed four hours later by a large armada of landing craft full of apprehensive soldiers heading toward shore.

One of them, Major John Shaw of the Royal Fusiliers, who was on an LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry), recalled, “At dawn on 6 June, I went on deck, and then, as senior army officer on board, I went on to the bridge. To my delight, the meteorologists had been right: the storm had died down. The view I saw from the bridge was one never to be forgotten. The whole of the Channel was full of head-to-tail lines of landing craft of various sorts. We were the most easterly line, and as far as I could see to the west, there were landing ships and escort vehicles. It was a most incredible sight, such as a child might lay out with his toys.”

Shaw added that at 7:25 am, the men of his Royal Fusiliers company began disembarking and wading ashore. “We could hear the guns firing from the beaches. We duly got into shallow water, and the ramps went down on either side. All the troops on board were supposed to go down them into two feet of water to wade ashore, but I found some of the men were still in the toilets, feeling too ill to get off the craft, and I had some difficulty getting them ashore.”

The Royal Fusiliers and Shaw, who had been wounded in 1940 at Dunkirk, were part of a contingent of nearly 29,000 British troops heading for Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

Among the huge contingent sailing across the English Channel was Major R.G.H. Brocklehurst of the 1st Battalion, Ox and Bucks. He said, “Our vessel was an American boat, quite small and converted for our landing by the simple addition of long wooden ramps that could be lowered on each side of the bows. Since we had reduced our first-stage needs to items that could be carried on foot, the only awkward ones were the company’s and platoon’s bicycles, which had been retained for message-taking along the road we knew ran behind the dunes of Ouistreham Beach.”

Brocklehurst was awed at the sight of the massive armada: “As we were on the left flank of the whole expedition, we could see a series of naval vessels patrolling to ensure that German MTBs [Motor Torpedo Boats, also known as E-boats] could not interfere should our armada be detected.

“The RAF had ensured clear skies from the Luftwaffe, and so, to our right as far as the horizon, we could see on this clear day orderly lines of vessels of all shapes, sizes, and types. They seemed no more than 500 yards apart, and steadily, we ploughed our way through a gentle swell towards the French coast. The total discipline and control fired enormous pride in those who were privileged to be a part of this mighty venture.”

Private Walter Scott, Royal Army Medical Corps, remembered, “Dawn had just broken, but I was instantly awake. As far as the eye could see, the Channel was full of ships, and they were not quiet. The noise was tremendous as the Navy blasted the German defences on the coast of France. I was not then afraid, after all, they were on our side. Fear would come later. I knew that history was being made, and I was part of it.”

In other landing craft were men of the 1st Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment. One of them, a sergeant major named Brooks, told a BBC interviewer in October 1944, “Every man in our battalion who went on the job was briefed. He wasn’t only told about the place he was going to, he was shown aerial photographs and ordnance maps and a large-scale model of the beach. We knew everything except the name of the country and the names of the places. Those were written in code.

“On the night of June 3rd, we embarked. On the whole of the 4th, we stayed in harbor on our LCI. In the evening, we pulled out into the Channel. We didn’t know until later that the show had been postponed 24 hours.

“The fellows didn’t worry much. We had a sing-song on board, and everybody was cheerful. We stayed there in the Channel all night, and then on the 5th of June, we sailed. By this time, maps had been issued to us, and we all knew exactly where we were going. They were proper maps this time, maps with names on them.

“We knew that this was the real thing, and we were all very glad to know that soon British troops would be on French soil again and hitting the Boche so hard that he would wonder how it all happened. The Channel was rough, and most of us were pretty seasick, but even that never dampened our spirits.”

Ray Buck, a member of the Merchant Navy, said that he was assigned to the Empire Capulet, one of 864 merchant ships involved in the operation, and one that was full of tanks, trucks, and ammunition. On D-Day, he noted, “We joined a vast convoy and sailed to Sword Beach … the objective of the British 3rd Division.

“Overhead, the skies were filled with Allied aircraft. We anchored close to the battleships HMS Warspite and HMS Ramillies and were surrounded by cruisers, destroyers, and rocket-firing landing craft … all firing continuously. Earlier that morning, a Norwegian destroyer, the Svenner,had been sunk in our anchorage by German torpedo boats, causing very heavy loss of life. The torpedoes passed between Warspite and Ramillies, hitting the Svenner in the boiler room. The torpedoes broke its back, and the ship sank.

“We also had a German coastal battery firing at us. Every now and again, a destroyer would go in at full speed and engage it. Although the German Air Force constituted no major threat to the landings, there were at least 22 sorties by [enemy] aircraft over the beaches. We were unlucky enough to be targeted by one. Cannon shells hit the Rhinos [big, square pontoons with an engine on the corner] that were tied alongside, and full of men and transport. This caused a fire and many injuries.”

Harry Lemon was a gunner aboard an LCI. Together with thousands of other ships, his craft sailed for Normandy. His was carrying soldiers from the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He said, “As we went in towards the beach [Sword Beach], something happened: we were blown up. We lost both ramps on each side of the ship, and there was a big hole in the bow below the water line. That was the only wet landing we gave the Warwicks!

“We had a full complement of men on board, and their equipment, too. They had their packs and rifles on, and because of the loss of the ramps, they had to climb down rope ladders, which was very tricky, despite the fact the water was only about six feet deep at the time.

“Once on the beach, we were stuck for 15 hours until the tide turned and we could be towed off. A craft behind us took a direct hit, and that was all panic. We were firing at a house way back on the beach. The skipper had said fire at that house because the Germans are in there, so we did and blew half the wall away. The Germans came tumbling out, and then they were no more.

“I had a colleague who lost a leg, and we were all covered in shrapnel. Bullets were pinging off the metal side of the gun I was manning.

“Once the Warwicks had left the beach, there were only about 20 of us on board. Much of the time, we were pulling soldiers out of the sea. A lot had their ‘Mae Wests’ [life vests] on under their packs, and as soon as they hit the water, they turned turtle and were easily drowned. That was the longest day, really the longest day.”

Asked to describe what the invasion was like, Lemon replied, “Have you seen Saving Private Ryan? If you have, the opening scenes on the beach really do give an idea of what it was like. The sea literally was red with blood.”

Britain’s Royal Navy played an indispensible role in the invasion. Twenty-year-old Petty Officer Lesley Friday was aboard the minesweeper HMS Gazelle, whose mission was to clear a section of the Channel of German mines. He was working down in the ship’s engine room throughout the morning of D-Day but could hear the constant rumble of the armada’s guns.

Coming up on deck some hours later, he was stunned by the sight of scores of dead men floating face down in the water, evidently having drowned before they could reach shore. He told an interviewer, “I am proud to have been there on D-Day, but I don’t reflect on the glory. You can’t, if you have seen the things I saw.”

Sailor Dennis Chaffer said that June 5 found him sailing from Southampton aboard Landing Craft, Flak 34, which was one of the invasion force escorts: “Just before dawn on the morning of June 6, we could hear loud explosions and see gun flashes. Our captain said that everything was going to plan. Whether he was right or wrong, we all knew that somebody was catching hell.

“As dawn broke, we found that we had been joined by other forces, and the English Channel was covered by a blanket of landing craft of all shapes and sizes. When we did reach the beach, we found that everything was going to plan. In fact, it was 10 pm that night before we fired a shot. We did help to shoot down a German bomber. This was the start of our battle with the Germans.

“E-Boats, human torpedoes, and radio-controlled explosive motor launches were thrown at us. We managed to overcome these problems, plus a direct bombing attack and intermittent shelling from coastal guns.

“For the next few weeks (two hours sleep a day for the first two weeks), nobody got any sleep at night. German planes dropped parachute mines which, if they touched the side of any ship or landing craft, would blow up.”

Richard Barnett, a member of a Scottish artillery regiment equipped with self-propelled Priests—basically an American 105mm gun mounted on a Sherman tank chassis—said, “Dawn revealed the full extent of the operation, with vessels of all shapes and sizes as far as the eye could see. Our training stood us in good stead as we ran in on the beaches with all guns firing to provide the protective barrage for the infantry regiment ahead of us.

“We were due to beach at H+1 hours—one hour after the initial assault—and precisely on schedule, the wonderfully efficient Navy grounded the LCT without mishap. Down went the huge ramp in a few feet of water, and our moment had arrived. All four guns and numerous other vehicles were driven off to add to an already cluttered beach.

“For reasons I have never fully understood, we were unable to get away from the beach for several hours, and it soon became clear that it was an unhealthy place to be. Not only were we open to the occasional attack from the air, but the few enemy guns still firing were targeted at the beach.

“As it was, our guns were soon called into action where they stood in a few feet of water, as we were by that time in direct support of the 6th Airborne Division, which had started the whole operation in the early hours. It was late afternoon before we were finally able to get away from the beach and head inland.”

The airborne had indeed started the operation. Parachute and glider troops from Maj. Gen. Richard Gales’ British 6th Airborne Division were landed shortly after midnight onto the eastern flank of the invasion area to isolate the battlefield so that the seaborne invasion force landing at Sword Beach would not be hit by a counterattack coming from the east.

The units comprising the 6th Airborne Division were Brigadier Nigel Poett’s 5th Parachute Brigade and Brigadier S. James Hill’s 3rd Parachute Brigade, the latter made up of Lt. Col. George Bradbrooke’s 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Lt. Col. Alastair Pearson’s 8th Parachute Battalion, and Lt. Col. Terence Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion. They were given the greatest number of missions that had to be accomplished if the British, French, and Canadian seaborne forces were to enjoy a successful landing at Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

Harold Packham, a 28-year-old craftsman in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME), recalled, “We were held up for two days due to bad weather just off the Isle of Wight. We traveled in darkness, and I was very seasick, but when dawn came, it was lovely weather, and we saw the French coast. Our warships were bombing the French coast, and the Germans were shelling us, and many craft were sunk.

“We should have gone in at zero 45 but, because so many craft had been lost, we went in at the first assault. We landed in six foot of water at Lion-sur-Mer on the extreme left flank next to the River Orne. Our job was to get the vehicles and equipment ashore.

“It was very difficult for the soldiers who were carrying heavy equipment and dropped in deep water, and many of them drowned. We tried to save some of them, but over the loudhailer, we heard, ‘Guns and equipment first,’ so we concentrated on getting the equipment ashore.

“For days, we landed vehicles and equipment, and our mechanics cleaned them and readied them for fighting. We felt constantly in fear of our lives, but we were so busy we just got on with it. Field Marshal Rommel had said this would be Tommy’s longest day but in fact, to me, it was one of the shortest. We were so busy, the time just flew.”

Another member of the REME was Scotsman John McOwan, an instrument mechanic. He said that his most vivid memory was “the armada of ships lying offshore. They stretched for as far as the eye could see.

“We waited for what seemed like an interminable amount of time before we could go on shore. We felt like easy targets for the Luftwaffe. A couple of ships were hit, and we just hoped and prayed that ours would not be one of the next ones. I remember that I did not even get my feet wet when we eventually came on shore as we were on landing-craft vehicles.”

Twenty-two-year-old Ken Oakley, an assistant to the beach master with a Royal Navy commando unit, noted, “Our job was to get everything organized on the beach, mark where the landing craft should come in, and call in supplies.

“The night before D-Day, the senior Army officer said to us, ‘You’re with the first of several waves. If you do not survive, we will send in the second wave, and if they do not survive, we will send in a third wave, and so on until we have captured the beach.’ That was a very nice thought to go to bed with.

“At 3:30 am on D-Day, we were woken up and told to get ready. At 5 am, we got into the Landing Craft, Assault to make for Sword Beach. There were several other LCAs around us. The sea was choppy, and many of the soldiers were sick. We were looking out for the dreaded stakes with bombs or mines attached to them, and when they came into sight, the coxswain steered towards a gap to our right. It was very, very tight, but he did a marvelous job and just missed one shell that would have blown us completely out of the water. And then, bang, we were on the beach, down the ramp.

“Everything had been kept so secret, we didn’t know what was going on around us at the time. We just saw our own landing. I was the beach master’s bodyguard, and the two of us ran forwards up to the beach. We were targeted by multiple mortars, and the fire from them was very, very heavy. All around us were landing craft coming in: bang, crash, wallop, and out you get, and everything was absolute chaos. It was 6:10 am, and we were among the first wave to hit the beach.

“A bit later, the commander came up to me and said that my mate Sid had been severely wounded, and could I help him. I went along the beach, and Sid was lying in the sand, very badly wounded. I pushed his kidney back into his body, and told him to be careful, I didn’t want him to spill that out again. I managed to get him along to the first aid post and they looked after him. Sid made a good recovery and was eventually the best man at my wedding!”

The bulk of the initial wave of seaborne forces landed at 7:25 am, led by the amphibious DD (duplex-drive) tanks of the 13th/18th Hussars that began churning their way toward shore. Wading in their wakes were the men of the 8th Infantry Brigade. A whole procession of Royal Engineers riding in AVREs (Armored Vehicle Royal Engineers)—the specialized armored vehicles called Hobart’s Funnies, named after their creator Maj. Gen. Percy Hobart—were also rolling toward shore.

All sorts of armored contraptions had been created by Hobart’s fertile military mind: the DD (duplex-drive) amphibious tank that could be launched some distance from shore and “swim” toward land; a Fascine tank that laid down a bundle of poles to fill in tank traps; a Crab tank that had a rotating drum with chains attached that beat the ground and detonated mines; a Bobbin tank that unrolled a giant roll of material to allow vehicles to drive across soft sand; the flame-throwing Crocodile tank; and a Plough tank that had two angled bulldozer blades on the front designed to unearth landmines.

Nineteen-year-old Ron Smith was a wireman aboard Landing Craft, Tank 947 that arrived at Sword Beach at 7:35 amwith some of Hobart’s Funnies on board. As the ramp went down, a German shell screamed in and hit one of the tanks on the landing craft, disabling it and totally blocking the craft’s exit ramp. Torpedoes carried on the landing craft then exploded, killing the colonel on board and three others. Smith helped wrap up the bodies as the battered LCT was forced to retreat and make its way back to Portsmouth.

“I helped to lay three of them out,” he said. One was Lt. Col. Arthur D.B. Cocks, commander of the 5th Assault Regiment Royal Engineers, the first British officer killed in the landings.

Naval Lieutenant Lambton Burn, who was also aboard LCT-947, recalled, “Shells are bursting all round. They are not friendly shorts from bombardment warships, but vicious stabs from an enemy who has held his fire until the final 200 yards. He is shooting well, shooting often. Mortar shells whine and burst with sickening inevitability. An LCT to port goes up in flames.

“There is a sudden jerk as our bows hit the beach. Down goes the ramp, with Sub-Lieutenant Monty Glengarry, RNZNVR [Royal New Zealand Navy Volunteer Reserve] and his party working like madmen at the bows. There is a roar of acceleration and Donald Robertson in Stornoway (the first Crab that managed to disembark) is away like a relay runner.

“Dunbar (the second Crab) moves forward. Colonel Cocks leans from his turret (he had elected to command from the Plough) and motions the other tank commanders to follow. But enemy fire is now concentrated on us. There are bursts on both sides and then—snap—two direct hits on our bows, followed by a third snap like a whip cracking over the tank hold.

“The first lieutenant is flung sideways against a bulkhead and lies stunned. Dunbar stops in her tracks, slews sideways, blocks the door. Another and greater explosion as the bangalore shafts of Barbarian (the Log Carpet AVRE, Captain Fairie in command) explode with a flash of red.

“Colonel Cocks is killed as he stands, and there is a scream from within his tank. Cold with anger, Tom Fairie moves Barbarian forward, tries to edge Dunbar to the ramp, but fails. He vaults from his turret and is joined by other tank men who strain furiously to bring chain and tackle to bear.”

Bob Littlar, 2nd Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI), said, “By late May, we knew that the assault would happen within 10 days or so, depending on the weather conditions, although no one still knew the exact date. We were told that another brigade had been selected for the initial assault, and that we would go in second as the penetration brigade, to get inland.

“On 2 June, the Friday before D-Day, they told us to be ready to go the following day. They shipped us down to New Haven harbor, where the LCAs were waiting for us to get on board. I think the idea was that we would sail out of New Haven at about 9 pm, but then the departure was postponed because of bad weather. So we were still in the harbor on Sunday morning, and they took us off the LCAs and fed us a fantastic lunch. We got back onto the boats at about teatime, feeling very happy because we had been so well fed!

“At about 9 pm that night, the four LCAs carrying our battalion quietly slipped out of the harbor and into the English Channel. We spent the entire Monday at sea, and we could see ships from horizon to horizon, all along the Channel. We’d all been issued with French francs, and to pass the time at sea, the lads were playing cards and gambling with the foreign currency.

“It was barely light at that time of the morning, but we could see that we were among warships of all sorts. As we got closer to the coast of Normandy, we could see smoke on the shoreline from the long-range battleship assault. We were all looking at this incredible sight when we were ordered to go below decks.”

Littlar added, “We had been issued with waterproof waders that can keep you dry up to the chest, like the ones fishermen wear. In theory this was great, but in practice it only worked if the water came up to your waist. Chaps were going under water and trying to wade out with these waterproofs absolutely filled to bursting.

“I got out a knife and started slicing the waterproofs of the chaps that were struggling to walk on shore wearing these things. I did this for about seven or eight blokes, the men in my group. Then I looked around and saw a sea wall, about two or three foot high, and I sheltered behind it on my own. My sergeant came up to me and said, ‘You’re not going to win this war on your own, get your men.’”

Shortly after 10 am, the men of the 2nd Battalion, KSLI, landed on Sword Beach near Hermanville-sur-Mer. They were supposed to ride atop the Sherman tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry and advance inland, but because of the logjam on and off the beach, the tanks were delayed. The men moved inland on foot down the D60 road without accompanying armor.

Littler continued, “I could see smoke, and smoldering tanks that had been blown up earlier. The seafront area had already been taken, but there was still some resistance and we were still being fired on.”

By 5:30 pm, Major Peter Steel’s company had reached German-held Lebisey, north of Caen. The KSLI’s advance had created a dangerous salient, so the unit was ordered to pull back, but not before Major Steel was killed.

Another KSLI soldier was Ernie Goodman, driving a Universal carrier that towed a 6-pounder antitank gun. “I was scared stiff,” he admitted. “I think most people were.” He made it through D-Day without a scratch, but had terrible memories of an incident that occurred a few weeks later when the rest of his gun team were all killed or wounded.

“A shell hit an apple tree above their trench, and the blast went straight down and killed two of them and injured the other,” he said. “The next night, they jumped in this trench thinking the same thing would never happen in the same place. And it did. I was the only one left.”

Ted Varley, a member of the 3rd Division Signal Regiment said that he was one of the first men to reach Sword Beach and vividly recalled the confusion and carnage: “I saw quite a lot of bodies floating along in the water, and people running around all over the place, and this and that flying around in the air. It was a bit chaotic, but it got sorted out. I was 20. I wasn’t frightened, I was apprehensive. You didn’t think about it, you just got on and did it.”

Sergeant Major Brooks, 1st Battalion, Royal Norfolks, recalled, “At about 9:45 am, the word came down from the bridge to make ready. This was followed by a few minutes stand-by. I made my way to the deck ready to lead my part of battalion headquarters ashore, and I had a good view of what was going on. Never before had I seen so many ships of all sizes and shapes as I saw that morning. Some were already returning from the shore empty, and others like ourselves were waiting their turn to go in.

“All types of naval craft were being used, and it was thanks to their skill that we never even thought about any opposition from the German Navy. As we closed into the shore, I could see houses and a narrow strip of beach, just like the models and photos we’d been shown at the briefing.”

Brooks noted that there was considerable enemy fire being directed his way. “I saw fountains of water suddenly shooting up on either side of us and I realized that for the first time in my Army career, I was under fire.

“Our battalion was sailing in three LCIs, and were now moving slowly forward, all in line. Then we hit the beach, and I saw the ramps go down, and the leading platoon was already running up the gangways and going ashore. Within five minutes, our party was on the beach, and we moved forward to our exit where a bulldozer was already at work making a roadway.”

Brooks continued, “We turned right and made our way along the road, where our battalion formed up ready for the march inland. There were several Sherman tanks moving slowly forward as the roads were cleared by sappers of the antitank mines along them. One of my sergeants major trod on one of these antitank mines, and it lifted him clean up and flung him into a hedge. He was completely unharmed—he was lucky.”

Brooks’ battalion marched about a mile south and then settled in while the commanding officer went to see the brigade commander. On the CO’s return, the battalion resumed the march until it came to a small village. “As we entered the village, the Boche began throwing a few shells over, and it was there we had our first casualties.

“As we hadn’t yet established a regimental aid post, our wounded were evacuated straight back to the beach. The village was cleared of the enemy by the commandos and our own assault brigade. We passed through it and took up a battle formation. To reach our next objective, we had to cross open ground. This was mostly cornfields, and we were under fire all the time from enemy machine guns.

“We didn’t even notice it much—we were all keyed up. The enemy was soon cleared, and after searching a wood, we went into it and waited for further orders to march on. So far, everything seemed to have gone like any field exercise, except that I knew our casualties were real ones this time, and there were no umpires about.”

Brooks’ unit had taken several prisoners. He said, “They looked a sorry lot and were dirty and untidy. I learned later that they were mostly Poles and Czech slave troops, and only their officers and NCOs were Germans. Then at 5:00, we received orders to move forward again and relieve the Royal Warwicks, who had met with some strong opposition on their particular objective.

“We went through two small villages. The snipers were still active, but we had no time to deal with them, and after crossing some marshy ground, we began to climb up a corn-covered slope towards our objective, but it was much too strongly held by the enemy. Through the coolness and efficiency of our CO, who was the last to leave, we withdrew and took up an all-round defensive position for the night. And so ended D-Day and my first day of battle.”

Another unit that landed at Sword Beach was Philippe Kieffer’s Free French Commando force. One of the last surviving members of that unit, Hubert Fauré, told a British reporter in 2014, “On May 25th, Kieffer gathered everybody and said we were going to carry out a decisive operation that would take us into France. He said half of those who went would fall, and that anyone who wanted to quit had to do so immediately. No one backed down, so we went to Southampton.”

After 10 more days of intense training, the men marched to their landing barges. “We were to leave as quickly as possible so everyone would get a bit of sleep,” Fauré said, “but it wasn’t possible, because the sea was too rough. All night long, all around us, the Allied planes were flying, dropping bombs on the coast. You can imagine the atmosphere.”

They arrived off Sword Beach just after 7:00 in the morning, timing their landing with the low tide. Fauré noted, “We were under fire, some men were killed. So we had to jump into the water, with 30 kilos of supplies, weapons, and ammunition.”

Fauré’s memories of the day were filled with the sights and sounds of flying munitions, smokescreens, battleships, and warplanes roaring overhead. The British reporter wrote, “The commandos separated and regrouped, lost their radio communications and made contact with civilians. Their mission was to disarm a casino transformed into a blockhouse, and doing so meant advancing through mine fields and blockades. Finally, when the day was over, their general gathered them in a café.”

“The general welcomed us,” recalled Fauré, “and said he was happy we made it. He gave each of us a glass of champagne, and we made a toast with the general.”

Another French commando was Leon Gautier, who was 17 in the spring of 1940 when Hitler’s forces marched in and occupied France. He managed to escape to England on one of the last French warships to sail and joined the Free French Forces under General Charles de Gaulle.

On D-Day, Gautier recalled British Lt. Col. Robert Dawson, commander of No. 4 Commando (of which Kieffer’s unit was a part) telling the French commandos that he wanted them to be the first on French soil. “We went in only a few seconds ahead. It was a symbolic gesture,” Gautier said.

Armed with a Thompson .45-caliber sub-machine gun, Gautier waded ashore, and with some of his comrades, headed for a concrete bunker that was spitting machine-gun bullets. Somehow, he escaped being hit and helped neutralize the enemy position.

Gautier grew reflective. “War is a misery. Not all that long ago, I would think that perhaps I killed a young lad, perhaps I orphaned children, perhaps I widowed a woman or made a mother cry. I didn’t want that, I’m not a bad man. You kill a man who’s done nothing to you. That’s war. You do it for your country.”

The French commandos, attached to Dawson’s No. 4 Commando, ran into tough resistance in Ouistreham, but they managed to clear it of enemy strongpoints. One particularly knotty problem was the remains of a casino at the nearby seaside resort town of Riva Bella. The Germans had leveled the building in 1942 and turned its foundations into a bunker.

Pinned down at an antitank wall by intense enemy fire, the commandos were taking casualties and unable to move. Kieffer learned by radio that six Sherman DD tanks of the 13/18 Hussars were approaching, so he decided to go find one but was wounded in the attempt. Still, he found a tank and guided it to Riva Bella, where it proceeded to destroy the casino/bunker. The French commandos were then able to storm the wreckage and clear the town of snipers.

Kieffer’s commandos suffered 44 casualties on D-Day, including 10 killed. They had died pour la France.

By 8 am, the first wave of invaders had overcome the defenders and was pushing inland. Eighteen-year-old Bill Fitzgerald, 1st Battalion, Suffolk Regiment, recalled the boat ride in: “We were the third in on the day. We got so far in, and then we hit something underneath, so we knew we were going to get wet. The beach master was there shouting: ‘Get off this bloody beach and don’t get killed!’

“The water was full of bodies, and they were mostly all Marine Commandos, but you couldn’t take too much notice. All you were thinking of was helping each other,” he said. “Looking at the bodies, you felt sorry about it, but you had a job to get on that beach and wait for your friends.”

William Hudson Harber, in charge of an American Rhino ferry, had sailed from the Isle of Wight at dawn on D-Day. He said, “The Rhino was carrying about 20 cars and lorries [trucks]. As we approached [our beach], there were three Marine landing craft already there. I said to my crew, ‘We have an easy landing here.’

“After discharging the cargo, I went for a walk along the beach towards the other landing craft. As I was walking, a German plane came and tried to machine-gun me down. I ran towards the landing craft to escape being killed. I then dived into a Marine command barge to save my life. All of the crew were dead. I had dived onto a pile of dead bodies.

“I returned to my landing craft and took it back out to sea to the other ships, along with my crew. I worked on the beach in Normandy for about two months, bringing supplies backwards and forwards. It was a daily occurrence to see floating body parts in the sea and washed up on the beach. Many snipers tried to kill us during our time in Normandy.”

Royal Engineers Corporal Frank Mouqué, who called himself “a little cog in a big wheel,” had the dangerous job

of defusing mines and other unexploded ordnance on the beach. He said, “We approached Sword Beach in a landing craft. We had all of our gear on our backs and a rubber ring around our stomachs to help keep us afloat. Let’s face it: the landing was very gory. You didn’t have time to think. The survival instinct kicked in.

“After reaching the beach, I ran up towards a parapet and searched for mines. After 12 hours of being on the go, we were exhausted and then had to dig a foxhole to sleep in.”

A Scottish soldier, James Churm, was a medic on a landing craft. He recalled, “My overriding feeling was one of terrible trepidation. Nobody knew what was happening until we got there. The amount of shipping in the Channel was fantastic, though. Every type of vessel you could think of was there.”

Another Scotsman, Jim Glennie, who landed at Sword Beach, remembered, “We didn’t see ourselves as heroes. We were just doing a job and we did what we got told to do.” He added, “I always wonder what the French people thought that morning when they woke up and saw all of the ships.”

A few days after arriving in France, Glennie was wounded, captured, and spent the rest of the war in a POW camp, Stalag 4b.

Major R.G.H. Brocklehurst of the 1st Battalion, Ox and Bucks, recalled that as he and his company ran ashore, they were taken under fire by a machine gun in a bunker, but, “The men swore that some of the sniping was from French women, ‘collaborateurs’ during the German occupation, who were none too pleased that we had arrived to chuck their boyfriends out!

“It was now 3 pm, and the tide was low, giving a wide expanse of wet sand over which all manner of men and machines were struggling to carry out their appointed duties. As [a soldier named] Page and I were a little way up towards our destination beside the right-hand exit, we were surprised to hear the sound of planes to our left. Coming in low were the only two Messerschmitt dive-bombers that evaded the RAF that day, I believe.

“We heard the rattle of their guns and saw the spurt of bullets in the sand ahead of us, apparently doing little, if any, damage. But as they were nearly overhead, we could clearly see the two wretched little bombs they carried released from under their wings to sail in a gentle curve down towards us.

“We flopped down on our bellies, and the bombs plopped into the sand a short distance away. Fortunately, the sand and mud which the River Orne had deposited over time immemorial was far too soft to detonate them on contact, and they sank to explode after a second or two and squirt up a column of disgusting mud, which broke up and came pattering down all over our backs. We did feel that to be excessively drenched on landing and then covered in mud into the bargain was a bit much!

“We crawled forward cautiously for a while, then I got fed up, stood up and started to walk forward, whereupon I was dragged down by Page who swore the snipers would get me.”

As the struggle for the beachhead continued, the battles for the Merville battery and Orne bridges were nearly over. The 9th Parachute Battalion’s assault on the Merville battery had not gone well. In fact, it had verged on disaster. Only about 150 of the 750 paratroopers who had left England had reached the battery. The rest were scattered for miles around. When Otway realized that no more men were going to suddenly appear, he ordered his men to attack the four casemates. It was a brave and bloody affair, but in the end, Otway and his men had accomplished their mission.

By contrast, Major John Howard’s glider assault on the Orne Canal bridge that would later be named Pegasus, in tribute to the British Airborne’s sleeve insignia, had gone off with barely a hitch. Within 15 minutes, the coup de main had succeeded, and several feeble German counterattacks had been halted. All Howard had to do now was hold onto the prize until Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade, made up of the 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 45th (Marine) Commandos arrived.

After fighting their way ashore under heavy German fire, Lovat’s men reached the 6th Airborne Division glider troops that had seized two bridges over the Orne waterways—Pegasus Bridge at Bénouville and Horsa Bridge at Ranville—at about 1 pmon June 6.

Lovat’s arrival was heralded by bagpipes being played by Private Bill Millen of Glasgow, Scotland. After Millen’s death at age 88 in September 2010, a British newspaper reported, “The unarmed, 21-yr-old piper marched up and down [Sword] Beach playing ‘Highland Laddie.’ He continued to play as his friends fell around him and later moved inland to pipe the troops to Pegasus Bridge.

“‘When you’re young, you do things you wouldn’t dream of doing when you’re older,’ Millen said in an interview long after he war.

“Walking among the wounded on the beach made Mr. Millen feel ‘helpless,’ he said, but for others, his music boosted morale at a critical time. The military high command had ordered pipers not to play because of fears over the level of casualties. That decision, though, was ignored by the brigade’s commander, Lord Lovat, who ordered Mr. Millen to lead his troops ashore to the skirl of the pipes.”

Lovat, the hereditary chief of the Clan Fraser, told Millen to play “Highland Laddie,” “Blue Bonnets over the Border,” and “Road to the Isles.”

Millen, who portrayed himself in the 1961 film The Longest Day,said, “Lord Lovat was seriously wounded at Normandy a week after we landed, hit by a lump of shrapnel. After the landings, I got to know him even better, and we became very good friends after the war, as I would often go up to see him at his home in Beauly near Inverness,” he said. “And when he died a few years ago, I played at his funeral.”

His famous pipes—which were silenced four days later by a piece of shrapnel—were donated to the National War Museum of Scotland, but they have since been relocated to the Pegasus Memorial Museum adjacent to Pegasus Bridge at Bénouville, France.

By the end of D-Day, some 28,845 men had come ashore at Sword Beach. Thankfully, British casualties—630 men killed and wounded—were relatively light (compared to Omaha Beach in the U.S. sector). But what had started out as a brilliant, well-planned, and perfectly executed amphibious operation soon turned into an exasperating slog. The drive toward Caen, just 10 miles away, quickly ground to a halt as the Germans put up a stubborn defense in the villages and fields north of the city. The British and Canadians failed to take Caen within 24 hours of the landings as they had hoped and planned.

As dusk on June 6 approached, so did the tanks of the 21st Panzer Division, which had been positioned at Caen. They were soon joined by those of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. After being pounded by British artillery, naval guns, and warplanes, the Germans pulled back to Caen, where they formed a steel shield around the city. At Tilly-sur-Seulles three days later, the Panzer Lehr Division arrived and lent its armored might to the defense, effectively blunting the British advance toward Caen.

In a further attempt to take Caen, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery sent the 7th Armoured Division—the famed “Desert Rats” of the battles in Libya—toward Caen, but a detachment of Tiger tanks halted them at Villers-Bocage on June 13.

The historian Antony Beevor wrote, “If Montgomery had intended to seize [Caen] as he stated, then he failed to put in place the equipment and organization of his forces to carry out such a daring stroke.” Beevor went on to say that Monty “would have needed to send forward at least two battle groups, each with an armored regiment and an infantry battalion.”

It would not be until July 20 that the city, or what was left of it, was declared secured. An estimated 3,000 local residents died in the crossfire.

The few remaining veterans of the Normandy invasion are now in their 90s and bent with age, beset with fading eyesight and mobility issues, and battling their last remaining enemy: time. But they will always look back upon June 6, 1944, as their finest hour.

As one British veteran, George Cutterham, remembered, “Everybody was frightened. Anyone who says they weren’t frightened must be telling a few fibs. But I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.”