By Major General Michael Reynolds

Malmédy is an attractive and prosperous town situated in eastern Belgium, 15 miles from the German border. But it was not always so. In 1871, it was part of the Prussian Reich (Empire) and it was only after Germany’s defeat in World War I that, under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, it was ceded to Belgium.

Needless to say, this forced change of nationality was unpopular with most of the inhabitants who continued to speak, and consider themselves, German. Then, on May 10, 1940, Belgium was again invaded by the Germans and Malmédy found itself returned to Hitler’s Third Reich. However, this new status was again short-lived. In September 1944, following the successful Allied landings in Normandy and subsequent race across France, American troops entered the town, and Malmédy once more became part of the Kingdom of Belgium.

Just three months later, at 0700 hours on Saturday, December 16, four mammoth 310mm shells fired from German railway guns fell on the town, killing 16 civilians and causing considerable damage. Hitler had launched his last great offensive in the West and, although neither the local inhabitants nor the Americans stationed in the town knew it, they were lying directly in the path of Waffen SS General Sepp Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army!

Hitler’s basic plan for his Ardennes offensive called for three armies under the command of Field Marshal Walter Model, the commander of Army Group B, to break through the American front in the Ardennes and Luxembourg and, with the main weight on the right flank, cross the Meuse River south of Liège and then exploit to the great port of Antwerp. This, it was hoped, would cut off the British and Canadian 21st Army Group and the U.S. Ninth Army from the rest of the Allied front, causing mass surrenders and depriving the Allies of their most important port. Indeed, Hitler saw it as the basis for another Dunkirk.

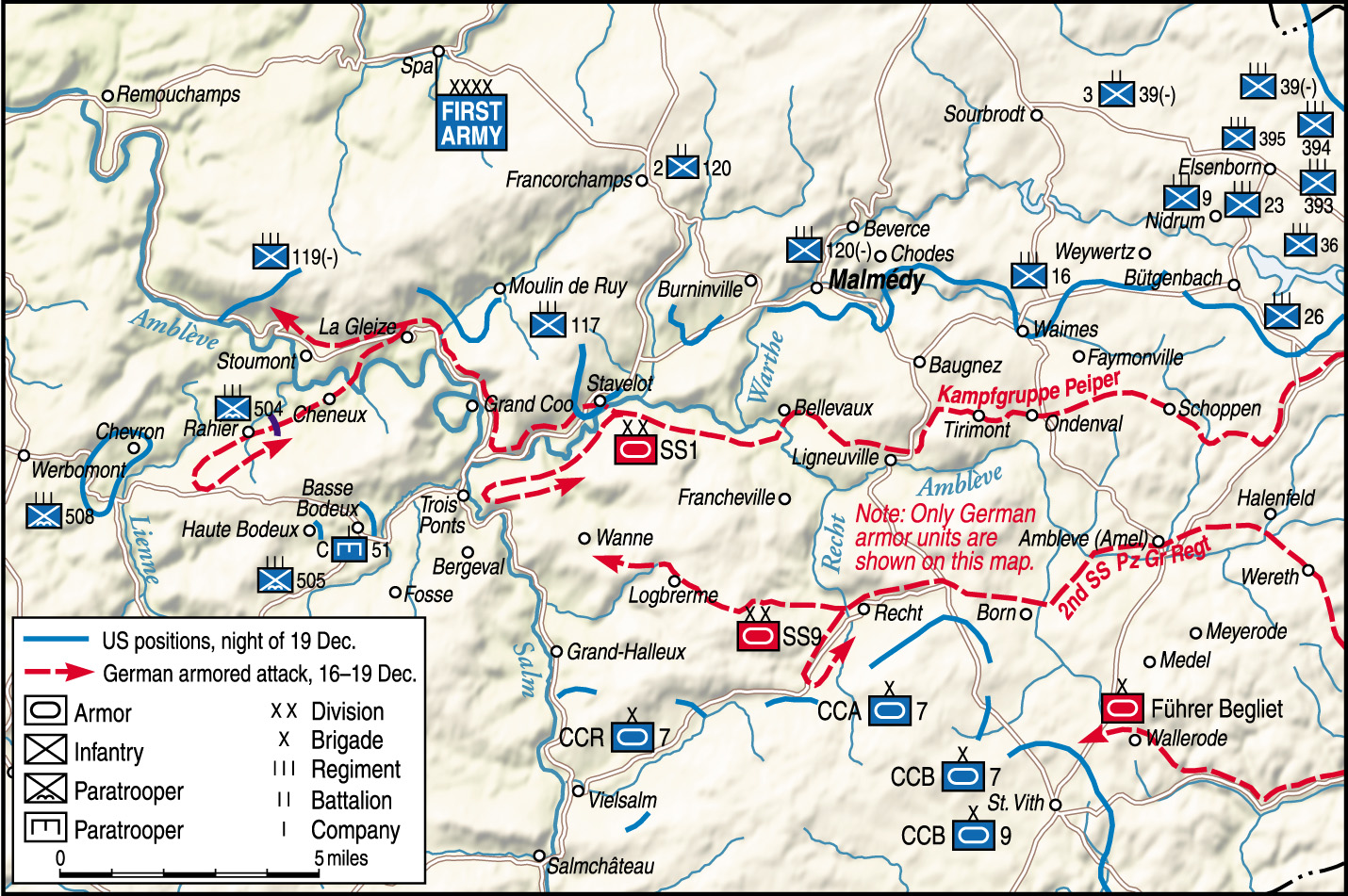

Sepp Dietrich had three corps to command: I SS Panzer Corps with the 1st and 12th SS Panzer Divisions (Leibstandarte and Hitlerjugend), plus one parachute and two Volksgrenadier divisions; II SS Panzer Corps with the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions (Hohenstaufen and Frundsberg), and the LXVII Corps with two Volksgrenadier divisions.

The plan called for the parachute and Volksgrenadier divisions to make a break in the crust of the American defense, and then form a hard shoulder on the right flank of the proposed advance. The 1st and 12th SS would then surge across the Meuse south of Liège in one all-powerful wave, followed by the II SS Panzer Corps, which would then exploit to the northwest and seize Antwerp. Malmédy was the first major objective of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend.

To aid the 1st and 12th SS Panzer Divisions in their dash for the Meuse, Hitler ordered a special operation, code-named Greif. It was commanded by SS Lt. Col. Otto Skorzeny, who had made his name in the daring rescue of Mussolini in 1943. In essence, he was to form two groups who would wear American uniforms and use captured American equipment. The task of the first group, comprising about 50 English speakers in teams of four or five, was to penetrate U.S. lines and then sabotage important installations and generally cause confusion.

The second, much larger group had the collective title of 150th Panzer Brigade; it comprised some 3,000 men and was to be equipped with armored vehicles. Its task was to move at night in three Kampfgruppen (battle groups, KGs), on parallel lines to the advancing panzer spearheads and seize bridges over the Meuse. During the event, some of Skorzeny’s four-man commando teams, using U.S. jeeps and uniforms, successfully penetrated American lines, with at least one reaching Malmédy and another getting as far as Huy on the Meuse.

After the war, Skorzeny said 44 of his men got through successfully. Whatever the exact number, there is no doubt that they achieved some success in that they made the Americans very jittery and security-conscious. Twenty-three of these commandos were captured and 18 executed by the Americans for contravening the rules of war by wearing enemy uniforms.

A number of American units were based in Malmédy in December 1944. Along with military government personnel and military police, there was a field evacuation hospital, a reinforcement depot, B Company of Lt. Col. Dave Pergrin’s 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 962nd Engineer Maintenance Company. These latter two units were part of Colonel Wallace Anderson’s 1111th Engineer Group.

Dave Pergrin, age 27, was a civil engineer by profession and a keen soldier by inclination. After graduating from Penn State College in 1940, he joined the Army and by September 1943 had risen to command the 291st. His unit landed in Normandy on June 24, 1944, and after the breakout through France reached the Ardennes the following September. By December, his companies were based in Malmédy, Stoumont, and Werbomont and were fully involved in road maintenance and an Army winterization program that saw them cutting timber in the forests and working sawmills in the local towns. Over the two months they had been there, Pergrin’s men had come to know the area and its people extremely well.

Life for these rear-based troops was really quite pleasant. After the German withdrawal in September, life in Belgium quickly reverted to normal; the Walloons (French-speaking Belgians) and Americans got on well together, and the tensions of the German occupation soon eased. However, it was not quite as relaxed in Malmédy where many of the German-speaking inhabitants treated the Americans with a sullen indifference. After all, some of the men from the town and the immediate area were still serving in the Wehrmacht!

Hitler’s Great Plan Goes Awry

Food rationing for civilians was still in force, but blackout restrictions were virtually forgotten, and by early December everyone had begun to think about Christmas. Certainly, no one thought the Germans were capable of taking any offensive action at this stage of the war, and the arrival of the four 310mm shells came as a great shock. Indeed, one of the most remarkable things about the American side on December 16 is that although the 99th Infantry Division was engaged in very heavy fighting just to the east and northeast of Malmédy throughout the day, the Americans in the town were seemingly unaware of what was happening and that they were about to be engulfed in a major German offensive. There is not a single entry in the daily log of Colonel Anderson’s 1111th Engineer Combat Group to indicate anything unusual, and Pergrin himself was certainly in the dark about what was going on.

He wrote later: “Captain John Conlin, our B Company commander in Malmédy came to see me [about the 310mm shells]… I immediately took off [for Malmédy]… and discovered great damage near the General Hospital…. After Conlin had taken over the job of taking care of the wounded and repairing craters in the road, I left Malmédy… I [did not] have the faintest idea that the spearhead of the Sixth Panzer Army would come crashing through in the next 24 hours.”

Fortunately for both the Americans and the civilians in Malmédy, Hitler’s great plan went badly wrong on the first day of his offensive. By midnight on December 16, the American 99th Division, although by then reduced to half-strength, was still holding most of its positions and the German Volksgrenadiers and paratroopers had failed to achieve any sort of breakthrough. Indeed, the Hitlerjugend’s armored KGs were still on the German side of the frontier! Similarly, the Leibstandarte’s advance was over 12 hours behind schedule, and its two leading KGs were also still in Germany.

On Sunday morning, December 17, Lieutenant Frank Rhea, a West Point officer commanding 3rd Platoon in B Company of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, decided to visit some of his men working on road maintenance between Waimes and Bütgenbach, just to the east of Malmédy. He had no idea that a major German offensive had started, but as he drove east he was puzzled by the heavy volume of U.S. traffic moving past him, heading west. He visited his work detail and then decided to go on to Bütgenbach to the 99th Division headquarters to find out what was happening.

On Sunday morning, December 17, Lieutenant Frank Rhea, a West Point officer commanding 3rd Platoon in B Company of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, decided to visit some of his men working on road maintenance between Waimes and Bütgenbach, just to the east of Malmédy. He had no idea that a major German offensive had started, but as he drove east he was puzzled by the heavy volume of U.S. traffic moving past him, heading west. He visited his work detail and then decided to go on to Bütgenbach to the 99th Division headquarters to find out what was happening.

On arrival, Rhea was told that German tanks had broken through just to the east of Bütgenbach. Needless to say, he rushed back to Malmédy to report to his company commander, Captain John Conlin. This alarming news was immediately passed on to Dave Pergrin. At about the same time, Pergrin’s superior, Colonel Wallis Anderson, heard from his liaison officer at V Corps headquarters that German tanks had been seen in the vicinity of his 629th Engineer Light Equipment Company at Bütgenbach earlier that morning but had been repelled. Although this was inaccurate information, Anderson naturally decided to take action. He ordered the 629th Engineer Light Equipment Company to pull back to Malmédy and told Pergrin to go to the town and assume command of all the engineer units there.

During his drive to Malmédy, Pergrin ran into an armored column of the 7th Armored Division moving through Trois Ponts, and on arrival in Malmédy he found another column of the same division transiting the town. Both these columns were heading south to help the battered and beleaguered 106th Division in the St. Vith area. The report of German tanks near Bütgenbach had made Pergrin very uneasy, but there was little he could do other than send out an exploratory jeep reconnaissance on the road toward Waimes, call for the machine guns and machine gunners of his A Company at Werbomont, and order roadblocks to be set up on all the major approaches to Malmédy.

At about midday, the jeep patrol brought back more disturbing news. German tanks were approaching Thirimont, only four miles southeast of Malmédy. They were part of KG Peiper, the leading element of the 1st SS Panzer Division. Pergrin realized at once that if these tanks turned northwest toward Malmédy there was virtually nothing he could do to stop them. Fortunately for Pergrin and his men, the eyes of the commander of the KG, SS Lt. Col. Jochen Peiper, were firmly set on Ligneuville to the south. As far as Peiper was concerned, Malmédy was the responsibility of the 12th SS Hitlerjugend.

The only uncommitted troops in the U.S. First Army on the morning of December 17 were the 99th Infantry Battalion (Separate); the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, less C Company, which was guarding 12th Army Group commanding general Omar Bradley’s tactical headquarters in Luxembourg City; and A Company of the 825th Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion. They were all based to the west of Spa. These three units were alerted for a possible move between 1100 and 1300 hours.

At roughly the same time, General Courtney Hodges, the First Army commander, asked for the 30th Infantry Division, part of General William H. Simpson’s Ninth U.S. Army, to be moved south to the Stavelot–Malmédy area as soon as possible. His request was granted, and units of the division received a warning order at 1140 hours. The first regiment, the 119th, was on the move at 1625 hours. The 117th and 120th Infantry Regiments were directed to the Malmédy area and the 119th farther to the west.

In Malmédy itself there had been something of a panic on that Sunday morning. Apart from Pergrin, his B Company, and the 962nd Engineer Maintenance Company, everybody else had “bugged out.” Pergrin knew that these few engineers could not possibly hold the largest town in the region without substantial reinforcements in the form of infantry, TDs, and artillery; nevertheless, he made the brave decision to stay on in the town.

At about midday, one of the serials in the 7th Armored Division column transiting Malmédy, B Battery of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, arrived outside Pergrin’s temporary headquarters in the Renz house on the St. Vith road. In the leading jeep were two officers who told Pergrin they were heading south through Ligneuville to St. Vith. Pergrin warned them that German armor had been seen just to the east of their proposed route and advised them to turn around and divert via Stavelot, Trois Ponts, and Vielsalm.

However, the two officers decided to continue the way they were heading and moved off at about 1230 hours in the direction of Ligneuville—with disastrous results. Little did they know that four miles down the road they would run into KG Peiper and become involved in the single largest massacre of U.S. troops in Europe in WWII.

As a result of this meeting with KG Peiper, 84 Americans died and 25 were wounded. Fifty-six men survived, of which seven became prisoners of war. There were no German casualties. Although the massacre took place in the hamlet of Baugnez, this tragic incident became known as The Malmédy Massacre. John Bauserman’s excellent book The Malmédy Massacre or this author’s book The Devil’s Adjutant: Jochen Peiper, Panzer Leader, describe the circumstances of the massacre in detail.

Message About a Massacre

At about 1430 hours, Dave Pergrin, having heard gunfire to the southeast, decided to make a reconnaissance in that direction. Sometime between 1515 and 1615 hours, after dismounting from his vehicle at Geromont and proceeding with one of his sergeants, Bill Crickenberger, on foot, he encountered three of the American survivors. He rushed them back to his headquarters and sent a message to his rear headquarters at Haute Bodeux stating that there had been some sort of massacre of American soldiers in the vicinity of Malmédy. At the same time, he ordered his own C Company, based 14 miles to the west at Stoumont, to reinforce him in the town.

Pergrin’s message about a massacre no doubt helped to focus minds at First Army headquarters, for at 1700 hours the 99th Infantry and 526th Armored Infantry Battalions and A Company, 825th TD Battalion, already on standby, were ordered to proceed to Malmédy at once. At about the same time, Pergrin sent a further message to his boss, Colonel Wallis Anderson, telling him that the German armored column had moved south from Baugnez toward Ligneuville. He had learned this from the B Battery survivors. This message made a major impact on Anderson. It meant that German tanks were only 16 miles from First Army headquarters at Spa and only 12 miles from his own at Trois Ponts.

By last light on the 17th, the immediate threat to Malmédy had been lifted, but there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the defenders were still in grave danger. At 2315 hours, Colonel Anderson, knowing the 629th Equipment and 962nd Maintenance Companies were of little use in an infantry role, ordered Pergrin to send them back to a location near the Meuse.

Between 0300 hours and dawn on Monday, December 18, major U.S. reinforcements reached Malmédy. Pergrin, with his 180 engineers, had bravely stayed in the town, but with only mines, demolition charges, light machine guns, and bazookas, for which they had precious little ammunition, the seven roadblocks they had set up on the major approaches into the town formed only a very primitive defense. One can only wonder what might have happened if the armored KGs of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend had broken through the stubborn American defenses at Krinkelt and Rocherath, or Jochen Peiper had been ordered to switch routes and advance through Malmédy!

The first infantry unit to arrive in Malmédy was Lt. Col. Harold Hansen’s 99th Infantry Battalion, consisting mainly of first-generation Norwegian Americans. It was completely in the town by 0300 hours. Shortly after this, the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, less two companies, and A Company of the 825th TD Battalion, less a platoon, came in and deployed on the east and south sides of the town. This group was subordinated to Hansen, and by first light a reasonable defensive posture had been adopted, absorbing Pergrin’s roadblocks.

At 1010 hours, Colonel Walter Johnson, commanding the 117th Infantry Regiment of the 30th Infantry Division, arrived in Malmédy, with his 3rd Battalion. They had been expecting to find the town in German hands and were relieved to find Hansen and Pergrin there with the situation under control. They were disgusted, however, with the scenes that met their eyes: abandoned American equipment, clothing, documents, and food wherever they looked. The 3rd Battalion immediately started to prepare positions on the southeast side of the town.

During the first daylight hours of December 18, KG Peiper, having advanced through Ligneuville the previous evening, attacked Stavelot, five miles west of Malmédy. Despite some heroic actions by the American defenders, the battle was over by 1000 hours and the town abandoned to Peiper’s column. Part of the defending force, the 1st and 2nd Platoons of A Company, 526th Armored Infantry Battalion and the one remaining TD of the 1st Platoon, 825th TD Battalion, withdrew to Malmédy, which they reached at midday.

The afternoon of the 18th saw a major strengthening of the Malmédy defenses. At 1300 hours the command post of Colonel Branner Purdue’s 120th Infantry Regiment was established in Bevercé, a mile north of the town. At this stage, the plan was for the regiment to act as a reserve. Accordingly, one battalion was deployed at Bevercé, one to the east of Malmédy at Chodes, and the other to the west of the town on the Stavelot road.

Following the deployment of the 3rd Battalion of the 117th Regiment on the southeast side of Malmédy, another battalion of the regiment, the 2nd, took up positions on the west side of the town between Burninville and Masta. The 1st Battalion of this regiment had been diverted to Stavelot where a major crisis had developed following its fall to KG Peiper.

On Tuesday, December 19, the commander of the 30th Division, Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs, decided to concentrate the whole of the 117th Infantry Regiment in the Stavelot sector and give responsibility for the defense of Malmédy to Colonel Purdue’s 120th Regiment. Accordingly, all existing units in the town were placed under Purdue’s command, Lt. Col. Ellis Williamson’s 1st Battalion of the 120th Infantry, supported by 1st Platoon, B Company, 823rd TD Battalion, and 3rd Platoon, A Company, 825th TD Battalion, relieved the 3rd Battalion of the 117th Regiment on the eastern flank, and Lt. Col. Peter Ward’s 3rd Battalion took up positions on the southwest side of Malmédy.

The 2nd Battalion was held in divisional reserve at Bevercé. Pergrin retained responsibility for the demolitions on the Warche River bridge, the large railway viaduct on the west side of the town, and the three railway underpasses on the southern side. His engineers, now relieved of responsibility for five of their original roadblocks, put out more mines, while his machine gunners thickened up the infantry on the railway embankment.

During the afternoon, K Company of the 3rd Battalion, 120th Infantry established strong positions on both sides of the Warche bridge. The other two TDs of 2nd Platoon, A Company, 825th were located near a house, now demolished, on the south side of the bridge. The four M-10s tank destroyers of 2nd Platoon, B Company, 823rd TD Battalion were held as a mobile reserve behind the railway embankment. Two 90mm, one 40mm, and two quadruple 50-caliber antiaircraft guns of the 110th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Robert Wilson, also joined the defenses and were placed on the high ground to the north of Malmédy in a position where they could dominate the southern approaches.

By last light on the 19th, the Malmédy defenses were in good shape, and the arrival of the 1st Infantry Division in the Butgenbach–Waimes sector ensured that the efforts of the 12th SS Panzer Division to break through toward the town from the east would be frustrated.

There was no fighting in the Malmédy sector on Wednesday, December 20, although intermittent artillery fire fell on the town. However, in the latter part of the day KGs X and Y of SS Lt. Col. Otto Skorzeny’s 150th Panzer Brigade assembled in the Ligneuville area for action against the town on the 21st. Kampfgruppe Z had been unable to reach the area in time for the attack but was seen as a potential reserve.

German Soldiers Moved Forward and One Yelled ‘Hey! We’re American Soldiers— Don’t Shoot!’ But They Didn’t Fool the Americans.

Kampfgruppe X was equipped with one Sherman and five Panther tanks disguised to look something like Shermans. It comprised two infantry companies of about 120 men each and a heavy company with two panzergrenadier, two heavy mortar, and two anti-tank platoons; it also had pioneer and signal platoons. Kampfgruppe Y had the same organization, but was strengthened by Sturmgeschutze (StuG, armored assault guns) instead of tanks.

Sepp Dietrich’s orders to Skorzeny were simple. On Thursday the 21st, he was to capture or at least neutralize Malmédy and, most importantly, to open up a route toward Spa for the 12th SS Panzer Division and also clear the road from Malmédy to Stavelot. This latter task was vitally important for the resupply of KG Peiper, which was now in trouble well to the west in the area of La Gleize and Stoumont.

German intelligence on Malmédy was sketchy. It was based on one of Skorzeny’s own commando patrols, which had penetrated the town on the 17th and found only Pergrin’s few engineers. The Germans had no idea that since then it had been strongly reinforced.

Skorzeny was given no artillery support for his attack, so he decided his only hope of success was to surprise the Americans. Both KGs were to attack in the dark, KG X from due south and KG Y down the main Baugnez–Malmédy road. Kampfgruppe X was targeted not on the town, but on the vital road junction south of Burninville. This initially required securing the Warche River bridge.

Unfortunately for Skorzeny, one of his men was captured near Malmédy on Wednesday afternoon and revealed, under interrogation, that the town was to be attacked at 0330 hours the following morning. By midnight, all the American units had been warned.

When Skorzeny’s men advanced down the hill toward Malmédy at 0300 hours on the 21st, Lt. Col. Ellis Williamson’s 1st Battalion of the 120th Infantry and the four TDs of 3rd Platoon, A Company, 825th TD Battalion were ready for them. The fact that this attack was launched nearly four hours before the attack by KG X on the south side of Malmédy would indicate that it was seen by Skorzeny as more of a decoy than a serious attempt to capture the town. By attacking that much earlier, he probably hoped to draw U.S. reserves to the eastern approach. The leading infantry company of KG Y ran straight into B Company, 1st Battalion, 120th Infantry near the railway crossing on the main road to the east of Malmédy.

Captain Murray Pulver, the company commander, described what happened in his book Longest Year: “Company B was given a position on the main road leading south to St. Vith… we quickly set up a road block at a small settlement called Mon Bijou… at 3 am, an American half-track came down the road followed by a column of tanks and other vehicles. The half-track hit a mine and lost its front wheels… when the half-track was disabled a group of German soldiers moved forward and one yelled ‘Hey! We’re American soldiers— don’t shoot!’ But they didn’t fool those two great soldiers. Sergeant Denaro let loose with his Browning automatic rifle and Sergeant Henderson fired and knocked out a TD following the half-track. Very soon the whole of 1st Platoon were engaged. The road was narrow with a high bank on the right and a gully on the other side making it impossible for the German tanks to advance. Barbed wire prevented foot soldiers circling us to get the mines [laid by Dave Pergrin’s men] off the road.… Very soon we began receiving heavy mortar and machine gun fire.… I think every gun in the 230th Artillery fired in our support… Things remained pretty hot until daylight. We could hear the tanks moving around but our artillery was giving them hell. Soon the tanks backed off, turned round and retreated… We lost two men killed and had four wounded.”

This was one of the first occasions when American artillery used the new and highly secret “Pozit” fuse. This caused a shell to burst above, rather than on contact with, the ground, thus showering fragments over a much wider area. This had a devastating effect on the attacking German infantry and the KG, having lost two StuGs, was stopped dead in its tracks. One of the StuGs had been abandoned practically intact after a high explosive round had caused minor damage at the rear.

Skorzeny’s main attack came at 0650 hours on the 21st, not 0400 hours as some reports say, against the American right flank. It will be remembered that the main Malmédy defense line was the railway embankment running roughly west to east on the south side of the town. B Company of the 99th Infantry Battalion, with two TDs of 2nd Platoon, A Company, 825th TD Battalion, was responsible for the Rue de Falize railway underpass. B Company, 526th Armored Infantry had its 2nd and 3rd Platoons with the other two TDs of 2nd Platoon, A Company, 825th covering the other two underpasses, while its 1st Platoon with two 57mm antitank guns was sited at the railway viaduct over the main road leading into Malmédy from the west.

Companies I and L of the 3rd Battalion of the 120th were located in the western part of the town, well inside the railway embankment, and they do not seem to have been involved to any extent in the day’s fighting. Company K, on the other hand, with a machine gun platoon of M Company and the four towed TDs of 1st Platoon, B Company, 823rd TD Battalion, sited as they were in the area of the Warche River bridge and the vital road junction just to its west, would bear the brunt of the German attack.

A large paper factory still stands just to the east of the bridge, and until a couple of years ago there was a lone house on the opposite side of the road. The headquarters of 1st Platoon, B Company, 823rd TD Battalion was located in this house with two of its TDs nearby; the other two TDs were north of the river. South of the paper mill was a large open area, now completely built over, stretching a good half-mile before the ground rises quite steeply. This area had been heavily mined and sown with trip flares by Pergrin’s engineers. Four M-10 TDs of the 2nd Platoon, B Company, 823rd TD Battalion were in reserve in a central position behind the railway embankment.

Six artillery battalions were capable of firing in support of the Malmédy defenses, and it will be recalled that the antiaircraft guns of the 110th AAA Battalion were deployed on the north side of Malmédy. In reserve, in the area of Bevercé, were the 2nd Battalion of the 120th, the rest of Hansen’s 99th Infantry, and B Company, less one platoon, of Lt. Col. George Rubel’s 740th Tank Battalion which had now arrived as part of Hobbs’s divisional reserve. Skorzeny’s men had an impossible task.

Despite all these forces there were two serious defects in the Malmédy defenses. First, the Americans had not appreciated that the road junction just to the west of the Warche River bridge was more important to the Germans than the town itself. Its capture would open up the roads to Spa and Stavelot. This misappreciation had led to only weak forces being positioned at the Warche bridge and road junction complex, and this weakness was further exacerbated by the fact that the boundary between the 117th and the 120th regiments was drawn too near to the vital road junction. As one regimental history puts it, “It must be said that the responsibilities of the two sister regiments at the vaguely defined inter-regimental boundary were none too explicit.”

The other incredible weakness was that the Warche River bridge could not be blown because the detonator for the demolition had been removed. It had always been the intention of the First Army chief engineer to withdraw Pergrin’s battalion from Malmédy as soon as it could be relieved by the 30th Division’s engineers, but Hobbs had argued for it to remain under his command, and he had won the day. In preparation for their expected withdrawal, however, Pergrin’s men had handed over responsibility for the demolitions on the Warche River bridge and the railway viaduct to the infantry. For safety reasons, the detonators had been removed.

Shortly after 0600 hours, the entire area around the paper factory was illuminated by flares set off by the attacking infantry and tanks of KG X. One part of the KG followed the Rue de Falize toward the railway underpass where the leading Panther tank “brewed up” on a mine. The 99th Infantry Battalion’s after-action report says the attacking column consisted of three U.S. jeeps, one half-track, an American M-8 armored car, a Tiger tank, and two Shermans. The 825th TD report speaks of a jeep, half-track, and Tiger being knocked out. In fact, there was only one Sherman in the whole of Skorzeny’s force, and the so-called Tiger was, of course, a Panther. For some two hours the accompanying infantry tried to breach the American defenses at the railway embankment, but B Company, 99th Infantry and the TDs of the 825th held firm and, helped by artillery using the new pozit fuse, the Germans were repulsed with, according to the 99th Infantry, 100 killed. The 825th TD section claimed to have captured two jeeps and an M8 in working order and rather magnanimously added in their report, “Company B, 99th Inf Bn also engaged the enemy at this point.” They admitted the loss of one of their TDs and to suffering four casualties.

Shermans, Tigers, and Panthers

As soon as flares illuminated the area in front of the paper mill, the main group of KG X headed straight for the Warche bridge. The fact that it could not be blown was a tragedy for the defenders. The history of the 120th Infantry Regiment says two 3rd Battalion outposts were overrun before the enemy reached the area of the paper factory. The lone house near it became the center of severe fighting. The TDs sited there took the attacking tanks under fire, but the house was soon surrounded by German infantry, and it was not long before the 823rd crews abandoned their TDs. They managed to remove or destroy the firing pins and sights on all four guns before most of them took refuge in the house along with three of Pergrin’s engineers and some members of K Company—33 men in all. By 0830 hours, one of the Panthers had crossed the bridge to the north side while others covered it from near the house.

When it began to dawn on the Americans that the Germans were focusing on the road junction and the boundary between the two regiments rather than the town, a crisis of confidence began to set in. At 0840 hours, G Company of the 2nd Battalion, 117th Infantry, on K Company’s right, was on full alert, and a section of 3rd Platoon, C Company, 823rd TD Battalion operating with it was moved to face the threat. A single gun of this section claimed to have destroyed a Tiger, a Sherman, a German manned M-10, and two more Panthers or Tigers! This claim was certainly never substantiated. Two days later, a sergeant of the 291st Engineers was told to check the whole area north of the Warche River for abandoned or knocked-out German vehicles—he found none!

Rumor then began to take over. At 1030 hours, an unconfirmed report said there were Germans in Meiz, a mile northwest of the road junction. This was untrue, but certainly by midday the Germans had driven two K Company platoons some distance to the north of the bridge and road junction area and had written down the third platoon. Survivors took shelter in the paper factory, and one of them, Pfc. Francis Currey, was to be awarded a Medal of Honor for his gallantry during this action.

Lieutenant Kenneth Nelson, commanding the machine-gun platoon with K Company, was to be awarded a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the fighting, and his platoon sergeant, John Van Der Kamp, the same medal. The situation was now considered serious enough to move the reserve 2nd Battalion of the 120th to the area of Burninville, north of the threatened road junction and to deploy two 90mm AAA battalions as far back as Francorchamps.

It is not clear how many, if indeed any, more Panthers crossed the river, but by early afternoon the situation had begun to stabilize. KG X was simply not strong enough to break through. Two Panthers had been disabled near the bridge, one by Francis Currey, and the paper mill position was holding firm. American artillery fired 3,000 rounds during this battle. Amazingly, the lone house too remained in American hands despite the fact that, believing it to be in German hands, the Americans took it under fire from the railway embankment at about 1000 hours with both artillery and machine guns.

One of the engineers and a K Company corporal eventually got out of the house in the early afternoon and managed to get back to the main U.S. position behind the railway embankment; there they reported that the house was still in U.S. hands and that only 12 men remained alive out of the original 33. Considering that tanks and infantry were fighting around the house for several hours, it is remarkable that anyone there survived at all; but this report, and similar statements that entire TD crews were killed or wounded, are not supported by the actual casualty returns.

The 30th Division report for December 21 shows B Company, 823rd TD Battalion had one man wounded and six missing; the 1st Platoon lost all four TDs (two were later recovered), two half-tracks, four jeeps, and a 1-ton truck with trailer; the 3rd Battalion of the 120th Infantry suffered seven men killed and five wounded. The 291st Engineers had one man killed and another wounded at the lone house and a third man killed by mortar fire. The 526th Armored Infantry counted four men wounded.

For Otto Skorzeny, observing the action on the high ground to the south, it was obvious that by midafternoon his attack had failed at considerable cost. His tanks had barely managed to cross the bridge, and none of his force had breached the railway embankment. The KG commander, who had personally led his men in the battle around the paper factory, came limping back on the arm of a medical officer, wounded in his rear end. By 1525 hours, the Germans were clear of the road junction, bridge, and paper factory area; at 1600 hours two M-10s of 2nd Platoon, B Company, 823rd moved through the Falize underpass.

Their after-action report noted that they fired on two German tanks concealed in buildings south of their positions. After first knocking off a corner of a building to expose the tank hiding behind it, three armor-piercing rounds sent the tank up in flames. Another tank in the vicinity was also destroyed, but it is believed that this tank might have been previously damaged by friendly artillery.

The tank behind the building was a disguised Panther later found beside the café at La Falize. The Operational Research Section of the 2nd Tactical Air Force visited the Malmédy area in early 1945. It found “Panthers all disguised as Shermans by the addition of thin sheet metal superstructures. One of these had been destroyed by the crew and the others by American artillery.”

At the end of the day, the American defenses had held and, despite all the problems, Malmédy was safe from the Germans. The 150th Panzer Brigade had lost 150 men killed, wounded, or missing. Skorzeny himself was wounded in the face by artillery shrapnel as he neared his original headquarters in Ligneuville that evening.

On Friday, December 22, Dave Pergrin was ordered, rather belatedly, to demolish the Warche River bridge, the massive railway viaduct, and the Rue de Falize underpass. It ensured that Malmédy became a fortress on its southern and western flanks, but it proved to be a waste of time and explosives. There would be no more enemy attacks on Malmédy, although intermittent German artillery fire continued to fall upon the town for the rest of December. However, it was the Americans rather than the Germans who now wreaked death and destruction on the town, its people, and its defenders.

Perhaps due to the mass evacuation of the town by all but Pergrin and his brave engineers on the 16th and 17th, there was a general misconception throughout First Army that Malmédy had fallen to the Germans. The fact that the better part of two regiments of the 30th Division, two independent battalions, and numerous subunits had moved into or through the town was virtually unknown in the chaos of the American bugout. Even the Stars and Stripes described Malmédy as being occupied by the enemy, as did the Belgian national newspaper, La Libre Belgique, and the Belgian Radio Nationale.

Even allowing for some confusion over the status of Malmédy, there can be no excuse for the bombing of the town at 1526 hours on the 23rd by six U.S. B-26 Marauders of the IXth Bombardment Division’s 322nd Bombardment Group, part of the Ninth U.S. Air Force. The flight, led by Major C.F. Watson, dropped 86 500-pound bombs on the town, in conditions the pilots described as “unlimited ceiling and visibility.”

Malmédy lies 33 miles from the intended target, Zulpich. The pilots admitted that they had failed to find their primary target and reported that they had bombed Lammersum, six miles farther on. Five of them reported excellent results. This is not surprising since much civilian property in Malmédy was damaged and many people were killed or injured. The 120th Regiment lost three killed, four wounded, and three men missing. After this raid, a First Army spokesman announced that as the Germans had entered Malmédy the town had been bombed. Peter Lawless of the British Daily Telegraph newspaper interrupted to tell him that he had just returned from the town, that there were no Germans there, and they had bombed their own troops.

Tragedy at Malmédy: 178 Civilians Killed

The following day, Christmas Eve, at 1400 hours in perfect visibility and with the snow-covered Malmédy valley looking like a Christmas card, 18 Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers of the Eighth U.S. Air Force struck again, causing massive damage. The main square and town center were leveled and many other parts of the town devastated by bombs and fires. The 120th Regiment casualty report for the day shows 98 killed, wounded, and missing, although some of these casualties occurred in the three companies of the regiment, which by then were involved in the fighting around Stavelot. The 291st Engineers, who did sterling work with their skilled manpower, had one man killed and the commanding officer of B Company, which had been in Malmédy since before the offensive started, was badly injured. No evidence to explain this bombing has been found in Air Force reports, and the unit responsible remains unknown.

On Christmas Day at about 1600 hours, there was a third and final air raid. Four B-26s of the 387th Bombardment Group dropped 64 general-purpose bombs on the town despite the ground-to-air recognition panels that had been displayed on many buildings. The intended target was St. Vith, 12 miles to the south, and aircraft-to-ground visibility was three to four miles.

The Malmédy town memorial names 178 civilians killed during the three air raids. Many more were injured. Although the IXth Bombardment Division acknowledged the mistakes made on the 23rd and 25th, the Ninth Air Force did not. The only official reference ever made to these tragic raids was when General Carl Spaatz, the ranking general of the U.S. Army Air Forces in Europe, mentioned an alleged misbombing of Malmédy during an Allied air commanders’ conference on January 4, 1945. In the postwar years, various excuses for these attacks have been offered in mitigation. The real reason why they happened is very simple and was known to those responsible within a few hours—human error.

By Christmas Day, the ground threat to Malmédy had disappeared, and the overall situation in the Ardennes had changed radically in favor of the Americans. Both the 1st and 12th SS Panzer Divisions had been pulled out of the line and were reorganizing for a new attack designed to cross the Meuse between Huy and Namur some 25 miles to the southwest. They had been replaced in the Malmédy and Stavelot areas by Volksgrenadiers in a defensive role.

On January 13, 1945, the 30th Infantry Division attacked south from the Malmédy sector as part of an offensive designed to finally eliminate the Bulge. Dave Pegrin’s 291st Engineers were with them. They had built a new Bailey bridge across the Warche at the site of the old wooden bridge which had seen so much fighting on December 21, and they cleared routes through the numerous minefields laid by the Germans to the south of Malmédy. By a strange quirk of fate, it fell to Pergrin’s C Company to uncover the bodies of the victims of The Malmédy Massacre in the field beside the Ligneuville–St. Vith road at Baugnez. A few days later, the 291st said goodbye to Malmédy forever.

The author first met Dave Pergrin in 1982 and now counts him among his close friends. He and Dave have spent many hours together in the Ardennes and in Pennsylvania, and through Dave the author has been privilaged to meet a number of veterans of the 291st Engineers. Over the years he has also met many veterans of the 30th Infantry Division, including Francis Currey, the 120th Regiment Medal of Honor recipient.

Malmédy is now a thriving town with excellent hotels, restaurants, and shops, and there are no signs of what happened more than 60 years ago—only at the memorials by the main church and at the Baugnez crossroads is one brought face to face with the tragic events of December 1944.

Michael Reynolds was a retired major general in the British Army. He was a veteran of the Korean War and the former director of NATO’s Military Plans and Policy Division.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments