By Blaine Taylor

Before the Battle of Quebec, which would ensure him immortality in British military annals, one of General James Wolfe’s captains said of him, “No man can display greater activity than he does.” Indeed, a full decade earlier, when he was a 22-year-old regimental commander in Scotland, another officer said of him, “Our acting commander here is a paragon. He neither drinks, curses, gambles, nor runs after women.” Wolfe, who was the son of a Royal Marine colonel and was devoted to his parents and late brother above all else, had only hunting and fishing as hobbies outside his martial pursuits.

Wolfe lived only to die a glorious death in battle. “All I wish for myself is that I may at all times be ready and firm to meet that fate we cannot shun, and to die gracefully and properly when the hour comes,” he wrote to his mother. “Being of the profession of arms, I’d seek all occasions to serve, and, therefore, have thrown myself in the way of the American war [against the French], though I know that the very passage [at sea] threatens my life, and that my constitution must be utterly ruined and undone,” he wrote.

Gangling and Awkward, Wolfe Was Nonetheless a Demanding Commander

Wolfe cut an odd figure. He was tall and thin, gangling and awkward. He had foregone the wig that was worn by the majority of men in his profession. Without a wig, his bright ginger locks dangled free. Although his pointed nose and weak chin made him considerably less than handsome, his blue eyes shone brightly in contrast to his pale complexion. As for his personality, he was quick to take offense, haughty, and egocentric. Yet to his credit he had great courage and exhibited unchecked bravery before and during battle.

Wolfe was both contemptuous of his own troops and supremely confident that he could defeat the French, even though he had never commanded a full army in battle before the Quebec campaign of 1759. He was known as a good training officer and battalion commander, but nothing more.

Wolfe called his men a rabble. “[They are] terrible dogs to look at,” he said. “They kill their officers through fear, and murder one another in confusion. No nation ever paid such bad soldiers at so high a rate. It is a doubt to me that there is another such collection of demons on the whole Earth!” Despite the rancor, his superior officer stated that his regiment was “the best in the whole army.”

Wolfe had utter contempt for American colonial troops, especially the Rangers. Ironically, it was the same kind of disdain that his foe in the Quebec campaign, French Lt. Gen. Marquis Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, had for the native Canadian and Indian forces serving under him.

Wolfe’s early military career included a failed raid on the French coast. He fought as an acting regimental adjutant at the Battle of Dettingen on June 27, 1741, where the British Army was engaged in a major action for the first time in 28 years. He then served as an infantry major at Falkirk Muir and Culloden in 1746 during the Jacobite Uprising that erupted the previous year. Returning to Holland, he was wounded at Lauffeld on July 2, 1747. From 1749 to 1757 Wolf was stationed in Scotland.

In September 1757 Wolfe participated in the British amphibious attack on the French Atlantic port of Rochefort. For his energy, dedication, and bravery during the expedition he was brevetted as a colonel. When King George II was preparing to send Wolfe to Canada to command a brigade under Maj. Gen. Lord Jeffrey Amherst, Prime Minister Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of Newcastle, informed the king that Wolfe was unsuited for the assignment because he was a madman. “Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals and make them mad, too,” replied the king. Wolfe subsequently participated in the successful storming of the French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island in Canada, his first action in then enemy-held North America. (Get an in-depth look at the wars that shaped the future of North America by subscribing to Military Heritage magazine.)

Life in the Military for Wolfe’s Rabble

Life in the British Georgian army for the redcoats was hard. Although King George I and his two successors opposed the system of purchasing officer commissions in the army, there was little alternative to it. During Wolfe’s day, the Georgian army was an unpopular and troubled institution. In Ireland, for example, British regiments earned no respect. The ranks were filled with all manner of thieves and scoundrels. Yet for many members of the lower classes, a career in the military was the only employment they could find.

This was particularly true for the Scots. They embraced the union with England in 1707 to form the United Kingdom with enthusiasm, to the point that by the 1760s between 20 to 30 percent of all officers in the British Army were Scotsmen. Promotion could be rapid if the situation warranted it, and captains could find themselves commanding regiments in the absence of field grade officers, but the ordinary society of private soldiers was disdained as drunken, disorderly, and vicious.

In Britain, the practice of quartering these rowdy men in private homes was a sore point just as it was in the American colonies where the Quartering Act of 1765 required colonists to give the redcoats food and lodging. Billeting them in barracks was adopted as a means of keeping the soldiers together and under eye, since the men were prone to trade their food money for alcohol when and where possible. Marriage was discouraged for common soldiers because of the sheer numbers of the women who traveled with the army in the field, all of whom had to be fed from the commissary stores.

On June 4, 1759, James Wolfe’s army, consisting of three brigades of 8,500 men, embarked from Portsmouth harbor. His force consisted of 10 regiments of the line, three companies of grenadiers, and three companies of light infantry.

The British fleet of warships and troop transports consisted of 162 vessels, and the voyage across the rough waters of the North Atlantic took just under a month. The British fleet anchored on June 26, 1759, four miles away from the heights of Quebec in the St. Lawrence River.

From that point, Wolfe gained his first view of the impregnable fortress sitting square atop sheer cliffs with daunting bluffs. Stone walls that were both high and thick made the city seem impervious to frontal assault. Wolfe immediately assessed his position in comparison with his skillful opponent. “The Marquis de Montcalm is at the head of a great number of bad soldiers, and I am at the head of a small number of good ones, who wish for nothing so much as to fight him, for the wary old fellow avoids an action, doubtful of the behavior of his army,” wrote Wolfe.

Wolfe & Montcalm

By the fifth year of the war in North America, there had never yet been the very type of set-piece battle that was so commonplace in Europe. Wolfe was determined at all costs to provoke one before winter set in, marooning his lesser force in the snow and ice of a faraway continent.

Wolfe faced another problem entirely unrelated to his land-based force. His Royal Navy ships contained 13,000 sailors who had to be fed. Moreover, the fleet had to return to the salt water of the open sea before the St. Lawrence froze over for the winter. In practical terms, that meant Quebec had to be taken before the first snowflakes fell. Wolfe therefore spent most of the summer 1759 looking for a back door through which to attack the city.

As for Montcalm, he had eight battalions at his command, five at Quebec proper with the other three dispersed elsewhere to prevent possible British landings, but all were within easy calling distance back to the fortress when needed.

Wolfe set up a battery from which to shell the city and oversaw his troops as they fought off Indian attacks that led to the scalping of sentries at night. He also worked hard to prevent an ever-mounting tide of desertions as the summer wore on without the hoped for decisive battle against the white-coated French regulars and their irregular Canadian allies. Wolfe was determined to win at all costs, asserting, “A battle gained is the highest joy mankind is capable of receiving to him who commands, a defeat is a situation next to damnable.”

A French fire ship attack against the anchored English fleet was repulsed by wary Royal Navy tars with grappling hooks. Meanwhile, Wolfe watched and waited for the opportunity to land his army in force.

An earlier landing attack on July 31, 1759, had been stopped by French fire, a heavy rainstorm, and Indian scalping parties. By the beginning of August 1759, the French estimated that 4,000 shells and 10,000 cannonballs had rained down on both the upper and lower towns of Quebec even before the main battle that was yet to come. Wolfe’s incessant activity was pushing the French to the brink of starvation and causing militia desertions. Despite all of this, Montcalm remained confident of victory. Wolfe’s guns might well destroy Quebec, but his redcoats would never take it, the French commander said. “Two months more, and they’ll be gone,” he told an aide.

Usually haughty and disdainful where his own subordinate brigadiers were concerned, Wolfe nonetheless called a council of war to present his plan of attack, which they unanimously rejected. Wolfe asked them to submit their own instead, which they did. To their astonishment, he accepted and implemented the plan to land his troops at L’Anse du Foulon. A French Catholic priest informed Wolfe that the French had left it lightly guarded.

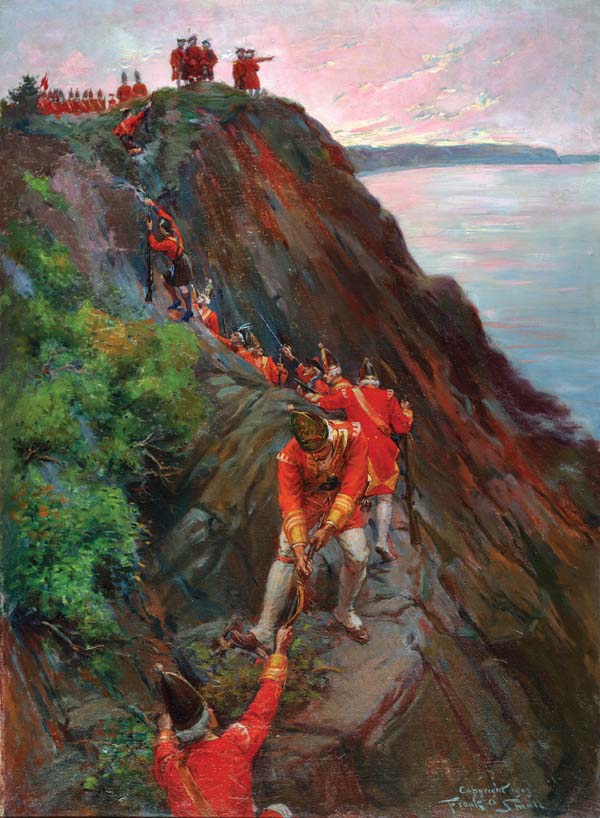

Securing the classic Royal Navy diversion to sow chaos downriver on the night of September 12, Wolfe sent ships bearing seven battalions upriver. At 11 pm the troops climbed down from the ships onto their transports. The flat-bottomed, oar-powered boats, each of which could hold 50 men, arrived at the cove at 2 am.

As the first boats headed toward the shore, they were challenged by French pickets who shouted to them to identify themselves. French-speaking British officer Captain Donald MacDonald replied that they were French marines bringing supplies to Quebec. The first troops ashore arrived at 4 am. The well-disciplined redcoats scaled the steep cliffs in silence.

Wolfe’s 4,500 British troops had formed a battle line across the plain by 7 am. Montcalm had expected the British to attack at Beauport to the east of the city. When he learned that Wolfe had managed to land his infantry at Foulon above the town, Montcalm sent an urgent dispatch to Colonel Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s 2,000-man flying column, which was stationed eight miles upriver at Cap Rouge, ordering them back to Quebec City. Leaving 1,500 troops behind as a covering force at Beauport, Montcalm rode to the city.

French Governor-General Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, had taken the initiative to send Canadian militiamen and Indians out from the city to harass the British troops. These sharpshooters took up positions in the woods on the British left and in cornfields on the British right. When Montcalm arrived at mid-morning, he was astonished to see the British formed up in two ranks for battle. He admired their cool discipline under the harassing fire, something his motley force lacked.

The Canadian sharpshooters, who had deployed on both flanks, picked off dozens of British soldiers. Among them was an English sergeant who Wolfe had reduced to the ranks for some sort of infraction. The noncommissioned officer was so angry with his commanding general that he deserted to the French before the demotion went into effect and swore revenge against Wolfe. On the eve of the battle, he specifically requested that he be allowed to join the Canadian sharpshooters so that he might have the opportunity to shoot Wolfe. The French granted his request.

Montcalm resolved at 9:30 am to attack the British for he did not want to allow them an opportunity to entrench. “If we give [the enemy] time to establish himself, we shall never be able to attack him with the sort of troops we have,” he told his chief of artillery.

Because he had so few regulars, at the outset of the campaign Montcalm had integrated the fittest of the Canadian militiamen with his regulars. These troops marched out of the city to engage the British. The French unfurled their flags 600 yards from Wolfe’s scarlet-coated infantry and grenadiers. Wolfe’s seven battalions were formed into two ranks in a half-mile-long line. Clad in his bright scarlet uniform, he walked his line to stiffen his troops. He was standing on a rise near the Louisbourg grenadiers when he was shot in the wrist. He stoically wrapped it in a handkerchief.

How General James Wolfe Died

The French attacked first, and twin volleys of coordinated fire struck the British lines at 150 yards. The renowned British discipline held firm. Wolfe himself gave the order to return fire with a single devastating volley at under 50 yards, followed by a charge of cold British steel bayonets and bloody Scottish Claymore swords.

The French line broke, and the men ran back to Quebec’s walls for shelter as fast as they could. The Highlanders dropped their muskets in favor of completing the slaughter with their broadswords.

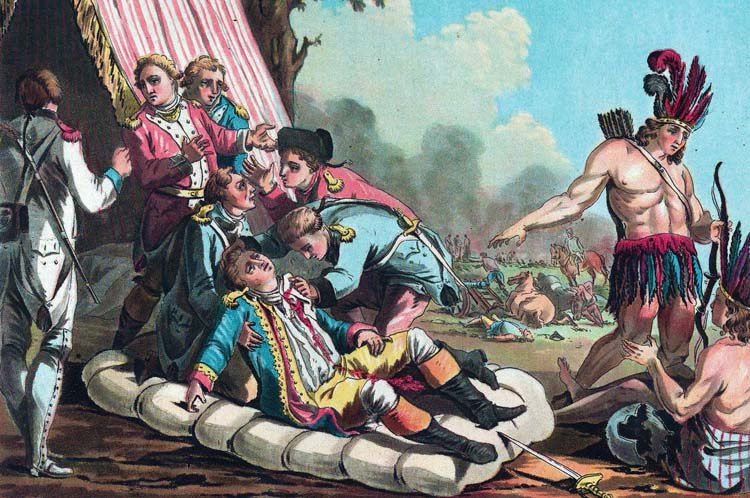

James Wolfe’s bright red uniform made him an easy target as he led the charge at the front of the Louisbourg grenadiers. He was shot a second time in the stomach and then a third time in right side of the chest. The English sergeant who deserted to the French claimed that he fired the musket ball that killed Wolfe, but there is no confirmation of it.

Wolfe sank to his knees, and a lieutenant in the grenadiers who rushed to help him initially thought that he was already dead. With blood oozing out of his mouth, Wolfe asked the lieutenant to help him get back on his feet so that his soldiers would not see him fall.

Wolfe declined a surgeon’s aid. “There’s no need now,” he said weakly, asking to be laid on the ground. “Go to Colonel Burton, one of you lads!” Wolfe said. “Tell him to march Webb’s regiment with all speed to the Charles River to cut off the retreat of the fugitives from the bridge.”

Those around him informed Wolfe of the French defeat. “God be praised,” he said. “Since I’ve conquered, I’ll die in peace.”

Wolfe’s Legacy

The battle had been won and the enemy defeated, but it was not over yet. Indeed, defeat was almost snatched from the jaws of victory as Bougainville’s reinforcements nearly arrived to reverse what had only just happened outside the city walls.

Montcalm had been driven back toward the gates of the city by the tide of retreating French and Canadian soldiers. He was mortally wounded in the leg and abdomen by grapeshot. He asked two soldiers close to him to hold him on his saddle until they were out of sight behind the walls of the town. At that point, Montcalm was taken to the house of a surgeon who informed him that the wound would prove fatal. He died the following morning.

British casualties in hour-long battle amounted to 58 men killed and approximately 600 wounded. Another 36 were slain immediately after the battle by French guns mounted on the ramparts of the city. French losses were 150 killed and 700 wounded.

The British won the battle, but what would happen next was unclear. Wolfe’s second in command, Brig. Gen. Robert Monckton, was severely wounded. Command ultimately devolved to Brig. Gen. George Townshend.

Townshend ordered the British troops to reform upon learning that Bougainville had arrived from his position upriver at Cap Rouge. But it was all for naught, for the French had no more fight left in them.

Vaudreuil had made up his mind to abandon Quebec. The survivors of the battle on the Plains of Abraham marched to Beauport where they linked up with the covering force. They then countermarched to Montreal, rendezvousing with Bougainville’s flying column along the way.

The British Army remained in Quebec on the verge of starvation during the harsh winter that followed. The return of the British fleet the following year solidified General James Wolfe’s decisive victory and the general’s legacy.