By Mike Phifer

While the soldiers and officers of the Japanese 15th Army fought fiercely to defend Mandalay in central Burma, they were alarmed to discover that British and Indian troops were dangerously close to attacking their supply depot at Meiktila, 90 miles to their rear. If this occurred, they faced certain destruction.

“Isn’t there some mistake?” asked a Japanese officer. “How can the enemy be so close in these back areas?” The officer along with three others had been ordered to remain in Meiktila after being told of two reports putting a small enemy force at Taungtha, about 40 miles to the northwest. The second report indicated Allied troops were approaching Mahlaing, not far from the airstrip at Thabutkon and only about 20 miles from Meiktila.

Just two days before, on February 23, 1945, an important meeting was held at Meiktila between the chief of staff of the Japanese Southern Army and chiefs of staff of various armies in Burma about the situation in central Burma, where the British were threatening Mandalay. Plans were made to mount an offensive against them.

The Japanese high command was not overly alarmed at the reports, choosing to believe it was a small-scale raid on Meiktila and that local defenses were substantial enough to deal with the raiders. Another report read that 200 enemy vehicles were spotted, but it should have read 2,000. For some reason the last zero was dropped from the message.

This was no raid, as the Japanese were to learn. The motorized 17th Indian Infantry Division and the 255th Indian Tank Brigade were racing toward Meiktila in a bold move that would jeopardize the Japanese hold on Burma.

During the previous year the Japanese 15th Army had suffered staggering losses in its failed attempt to capture Imphal and Kohima in northeast India. The purpose of the Japanese offensive had been to forestall a British invasion of Burma and cut the movement of supplies between India and China. Elsewhere, the Japanese 28th Army also suffered defeat at the so-called Admin Box in the Arakan region when it tried to overrun the Indian 7th Division’s administrative area. With the Japanese limping back to Burma in early July 1944, the British quickly struck before the Japanese Burma Area Army—which comprised the 15th, 28th, and 33rd Armies—could regroup.

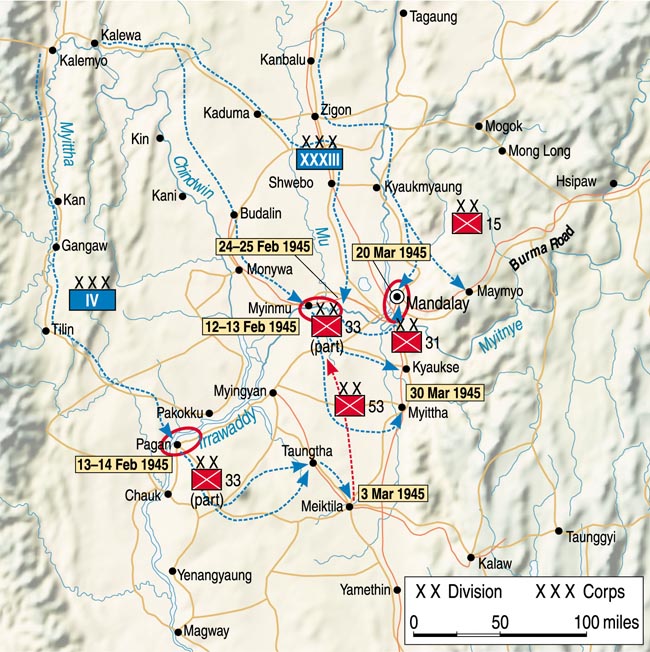

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander in South East Asia, under the operational name of Capital, ordered the British 14th Army under Lt. Gen. Sir William Slim to advance into central Burma to capture Mandalay, the link between the Japanese 15th and 33rd Armies. With this town in Allied hands, any chance the Japanese had of smashing communication between India and China had vanished like dry ground during a Burmese monsoon. While the 14th Army advanced on Mandalay, the Chinese Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC) was to push south and link up with Slim at Maymo, east of Mandalay.

Slim continued his pursuit of the retreating Japanese through the mountainous jungle toward the Chindwin River. Slim predicted that the new commander of the Burma Area Army, Lt. Gen. Kimura Hyotaro, would deploy his forces on the Shwebo Plain, which was located north of Mandalay between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, to defend the country’s ancient capital. The hard-charging British general meant to destroy the enemy in the open ground with his superiority in tanks and aircraft.

The 14th Army crossed the Chindwin and pushed southward in December. Japanese resistance was light, and it was becoming clear to Slim that Kimura had no intention of deploying his army on Shwebo Plain. Kimura had ordered his men back across the Irrawaddy, which forced Slim to come up with a new plan. Slim unveiled the revised plan on December 17 to his superior, Lt. Gen. Sir Oliver Leese, commander of Allied Land Forces South East Asia.

The success of Slim’s bold plan, named Extended Capital, depended on deception, speed, and surprise. Slim intended to deceive Kimura into believing the entire 14th Army was attempting to capture Mandalay, while in reality only one of its corps—the XXXIII Corps—was tasked with the direct assault.

While that attack was under way, the 14th Army’s other corps, Lt. Gen. Sir Frank Messervy’s IV Corps, would make a rugged journey through the Myittha (or Gangaw) Valley to the Irrawaddy River, where it would cross the wide river at Pakokku. Once across, the IV Corps would advance behind Japanese lines and capture Meiktila. This town, which was located between two lakes, was the enemy’s key supply depot through which the majority of supplies moving inland from Rangoon had to pass before being transported north.

Kimura would have no choice but to attempt to recapture Meiktila, while at the same time battling XXXIII Corps at Mandalay. Slim figured the Japanese commander would have to commit all the forces he had in central Burma, allowing the 14th Army to smash them, with IV Corps at Meiktila being the anvil while XXXIII Corps pushing south from Mandalay was the hammer. Slim was confident of victory.

The British and Indian troops that made up the 14th Army had come a long way since the dark days of 1942, when they were driven out of Burma by the Japanese. Low morale, rampant disease, lack of supplies, and a belief that the Japanese could not be beaten in the jungle plagued the troops. British high command began to change all that with better training and tactics in jungle warfare, a major reorganization, and better equipment for the army’s divisions. As for shortages of material, they were able to mitigate that weakness by relying more on air supply. Slim worked hard to restore the army’s morale and gave it a mission to destroy the Japanese Army, which was preparing to meet them under its new commander on the east side of the Irrawaddy.

The 1,350-mile-long Irrawaddy originates in the Himalayas and flows through the center of the country, cutting a swath through an open plain before fanning out in a delta that empties into the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea. Kimura intended to defend southern Burma and the valuable oilfields near Yenangyaung and the much needed rice-growing areas of the Irrawaddy Delta.

To do this, Kimura positioned the 33rd Army, which was composed of the 18th and 56th Divisions and a regiment from the 49th Division from Lashio, west to the mountains to the northeast of Mandalay. Along the Irrawaddy from Mandalay to Pakokku was the 15th Army under Lt. Gen. Shihachi Katamura, which was made up of the 15th, 31st, 33rd, and 53rd Divisions, the latter of which was held in reserve. The 28th Army, consisting of the 54th and 55th Divisions, 72 Independent Mixed Brigade, and a regiment from the 49th, held the area around the Yenangyaung oilfields to the Arakan and the Irrawaddy Delta.

In reserve Kimura placed the 2nd Division, the rest of the 49th Division, and the 24th Independent Mixed Brigade. Kimura also had under his command two divisions of the Indian National Army (INA). To protect the key supply depot at Meiktila with its surrounding airfields, the Japanese had two airfield defense battalions and an antiaircraft battalion.

Kimura believed Slim would attempt to take Mandalay by crossing the Irrawaddy both north and southwest of the key town in an attempt to envelop it. By counterattacking with the 15th Army, Kimura intended to hold the east bank of the Irrawaddy and keep Slim out of Mandalay. Once the monsoons came in early May, Kimura believed the 14th Army’s supply lines would be badly stretched, causing its troops to be unable to continue their attack and possibly forcing them to fall back to the Chindwin.

The British commander would have to use deception to make the Japanese think Mandalay was their key objective and commit their forces there, while at the same time keeping the Japanese unaware of IV Corps’ drive south from Tamu and down the Myittha River Valley. Their 328-mile journey was made more difficult as there was nothing but a dirt track to travel on, forcing IV Corps to build their own roads. If Slim was to be successful and keep his two corps fighting separate battles supplied with 750 tons a day, which was scheduled to rise to 1,200 tons in March when the fighting for Meiktila would be in full swing, he needed to depend heavily on air transport.

This became increasingly more difficult when Slim learned on December 10 that three U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) squadrons, totaling 75 aircraft, roared off to China to help Chinese forces there. “The noise of their engines was the first intimation that anyone in 14th Army had of the administrative crisis now bursting upon us,” said Slim.

To make up for the loss, the airlift operation had to be recalculated and replanned. This meant that XV Corps, which was to launch an attack in the Arakan to keep Japanese forces occupied there and capture the key islands of Akyab and Ramree with their valuable airfields, would suffer reduced airlift.

More aircraft became available when two Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons that had been resting and retraining were quickly brought back into service. Two Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons also arrived in late December. In January and February 1945, two more squadrons arrived, and two of the USAAF squadrons returned.

Although Slim was heavily relying on airlift, some supplies would be moved by road and others by water. In January, Slim ordered his chief engineer, Maj. Gen. W.F. Hasted, to construct vessels and move supplies down the Chindwin to the Irrawaddy. By the end of the campaign, the engineers had built 541 craft.

On December 18, Slim met with his two corps commanders, Lt. Gen. Sir Montague Stopford of the XXXIII Corps and Messervy of the IV Corps, to explain his plan and stress the need for speed. The corps commanders wasted no time in getting their men moving. The XXXIII Corps, consisting for the campaign of the 2nd British Division, 19th and 20th Indian Divisions, 254th Indian Tank Brigade, and 268th Indian Infantry Brigade, continued its advance toward Mandalay with the 20th Indian Division on the right, the 2nd British in the center, and the 19th Indian Division on their left flank.

Originally, the 19th Division was part of IV Corps, but it was now ordered to serve with the XXXIII Corps, which Slim hoped would deceive the Japanese into believing that IV Corps was advancing on Mandalay as well. To further deceive the enemy, a dummy IV Corps headquarters was set up at Tamu, where all radio communication between XXXIII Corps and 19th Division had to pass.

Meanwhile, IV Corps was to keep radio silence. Elements of this corps, now consisting of the 7th and 17th Indian Divisions, 255th Indian Tank Brigade, 28th East African Brigade, and the Lushai Brigade, headed south from Tamu for Pakokku. Its journey was to be a tough one as Hasted and his engineers had to construct a new road for IV Corps to move on.

Hasted figured he could build a new road in 42 days. To do this he was going to use “bithess,” which was Hessian cloth treated with bitumen, making it water resistant. The overlapped bithess strips were used to surface the newly leveled and tightly packed road. Besides building a road, the engineers would have to build rough airstrips along the way for supplies to be delivered to IV Corps.

The Lushai Brigade, made up of Lushai and Chin levies, along with Indian Army battalions, led the way of the stretched-out IV Corps, which had some of its units still in India. The Lushai Brigade was given the task of capturing the town of Gangaw held by a dug-in rear guard of the Japanese 33rd Division. Heavy rains in the first week of the month delayed the assault until January 10. To aid the attack, four squadrons from the USAAF 12th Bombardment Group blasted the Japanese positions, followed by Hawker Hurricane and Republic Thunderbolt fighter bombers conducting strafing and bombing runs. Then the Lushai Brigade attacked. The Japanese troops put up a brief, determined resistance before retreating. Gangaw was cleared the following day.

The 28th East African Brigade now took over the advance. It was impossible to prevent the Japanese from detecting troop movement down the Myittha Valley, but the 28th, operating under the pretext that it was the 11th East African Division, intended to deceive the Japanese that its objective was the Yenangyaung oilfields.

In the meantime, the XXXIII Corps continued its advance on a broad front. The 19th Indian Division advanced on the town of Shwebo, located about 50 miles northwest of Mandalay, from the north and east. Concurrently, the 2nd British Division advanced on Shwebo from the northwest. The town was finally cleared on January 10. From there, Maj. Gen. T.W. Rees ordered his 19th Indian Division to cross the Irrawaddy north of Mandalay at Thabeikkyin and Kyaukmyaung.

By nightfall on January 17, the last brigade of the 19th Division had crossed the Irrawaddy to reinforce the bridgeheads established a week before. While this was under way, the Burma Area Army was planning a counterattack into the Shwebo Plain. But with the troops of Rees’s division on the east bank of the Irrawaddy, Katamura meant to wipe them out before they became more established.

Sending part of its force to hold the bridgehead at Thabeikkyin located about 55 miles from Mandalay, the 15th Division, along with the 53rd Division of the 15th Army, concentrated on the bridgehead at Kyaukmyaung, 40 miles from Mandalay. During the last week of January, the Japanese troops bloodied themselves there by launching fierce night attacks against the entrenched British and Indian troops. Even with heavy artillery support, the night attacks could not budge them.

With the 19th Division firmly planted on the east side of the Irrawaddy, Rees consolidated his two bridgeheads and prepared to push south to Mandalay. Meanwhile, the 20th Division was preparing to cross the Irrawaddy near Myinmu and advance on Mandalay from the south and west. Before the 2nd Division crossed, it first had to clear out remaining Japanese troops on the west bank of the Irrawaddy where the mighty river bent at Sagaing. Then when boats became available, the division was to cross the Irrawaddy and join the 20th Division.

The spread out IV Corps continued its push for Pakokku with the 28th East African Brigade leading the way and the 7th Division following it. After leaving Gangaw, IV Corps soon encountered hundreds of downed trees across the track left by the retreating Japanese to slow their advance. The engineers quickly removed them. On January 28, the 89th Indian Brigade of the 7th Division took Pauk about 40 miles west of Pakokku.

As they continued their advance toward the Irrawaddy, Messervy and the 7th Division commander, Maj. Gen. G.C. Evans, had to decide where to cross the river. Shifting sandbars had created a number of channels, making a direct crossing difficult. Patrols were sent out to check possible crossing places, and aerial reconnaissance photos were studied.

Pakokku was closest to Meiktila, but it was also the most obvious crossing point. Evans wanted to cross near the village of Nyaunga where the river was at its narrowest. A crossing at Nyaunga would have to be made diagonally from about two miles upriver instead of directly across to avoid the open sandy beaches on the western bank, which would be visible to the Japanese on the east side of the Irrawaddy.

Facing Messervy on the east bank of the river was the 72nd Independent Mixed Brigade of the 28th Army and the 214th Regiment of the 15th Army along with some INA troops. As this area was the boundary between the two Japanese armies, coordinating a response from the defending units would be slower because they were under different chains of command.

To deceive the Japanese, Messervy and Evans developed a plan named Operation Cloak in which Pakokku would be captured, giving the impression this was where the main crossing would take place while a diversionary crossing was made farther downriver at Pagan. To add to the enemy’s confusion, the 28th East African Brigade was to conduct a feint at Chauk farther to the south.

Once the 7th Division was across the river, the 255th Indian Tank Brigade was to capture Meiktila and the surrounding airfields. Messervy did not believe a tank brigade was enough to hold Meiktila for any length of time and sought Slim’s permission to have the 17th Indian Division mechanized. Slim agreed, and the division, which was still in India, was given the vehicles of the 11th East Africa Brigade and the 5th Indian Division. This was enough to allow two brigades of the 17th Division to be mechanized. It was decided the remaining brigade would be flown in once an airfield near Meiktila was captured.

By February 10, the 7th Division had fought its way to the Irrawaddy after the 114th Brigade had dislodged stiff Japanese resistance at the Kanhla crossroads about eight miles from Pakokku. In the meantime, the 89th Brigade had reached the river opposite Pagan and sent across a Sikh patrol after dark. The 33rd Brigade cleared the area around Myitche and prepared to cross at nearby Nyaungu. The 28th East African Brigade secured Seikpyu on February 12 after encountering stiff resistance and prepared to cross the river to Chauk.

Farther to the north on the XXXIII Corps’ front, the 20th Division prepared to cross the Irrawaddy near Myinmu on the night of February 12. Before it did, 50 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers pounded the concentration of Japanese artillery that afternoon, followed by a squadron of Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter bombers. With the coming of darkness, the 100th Indian Brigade began crossing near Myinmu, while the 32nd Indian Brigade crossed seven miles downriver at Cheyadaw.

A lieutenant with the 1st Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment of the 32nd Indian Brigade (often an Indian brigade had one British battalion in it) recalled the crossing: “We set forth like a crocodile of rubber dinghies with an outboard motor on the front one, which kept on conking out. We were met by machine-gun and mortar fire which was not very effective.”

Overhead a noisy RAF aircraft patrolled up and down the river attempting to drown out the sound of outboard motors as the boats struggled across the fast-flowing river. Despite some motor problems and boats drifting downstream, the two brigades had established bridgeheads by daylight on the February 13.

That same day, IV Corps’ 7th Division was getting into position to cross the Irrawaddy in the early morning of February 14. At the Nyaungu crossing, a detachment from the Special Boat Section and Sea Reconnaissance Unit did a final check of the far side of the river before the lead company of the 2nd Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment, 33rd Brigade rowed out at 3:45 am on February 14. An hour and a half later the Lancashire men reached the east bank undetected and seized the high ground there.

The rest of the battalion’s crossing did not go so well. To maintain silence, the boats’ outboard motors had not been warmed up prior to the battalion setting out. This caused problems as the motors began to stall midstream. Some of the assault boats also began to leak.

The crossing fell behind schedule. Because of the strong current and motor trouble, the assault boats drifted downstream past their landing beaches. At daylight INA troops fired on them with machine guns. Within minutes two company commanders were dead, and a few boats were sunk. To aid the troops, air support was called in while the artillery and some tanks provided covering fire to the boats as they made their way back to the west bank.

The 4th Battalion of the 15th Punjab Regiment was now sent in. With no concern now for silence, the outboard motors were allowed to warm up before the boats headed across the river at 9:45 am. The assault went well, and within two hours the whole battalion was across the river. By nightfall most of the 33rd Brigade had crossed the Irrawaddy.

Farther downriver at Pagan, the 1/11th Sikh Regiment had an easier crossing when, after being initially driven back by machine-gun fire, a small boat with two INA soldiers carrying a white flag appeared, revealing that the Japanese had left Pagan. The Sikhs quickly crossed, and after some light resistance 280 INA troops surrendered while others retreated south.

But at Seikpyu things did not go well. The Japanese 153rd Regiment of the 72nd Mixed Independent Brigade launched a fierce attack on the 28th East African Brigade, driving it back about 12 miles to Letse. Despite falling back, the East Africans had drawn off enemy troops from Nyaunga.

The bridgehead near Nyaunga was made more secure on February 15 when part of the 89th Brigade crossed the Irrawaddy. With not enough troops to counterattack, the Japanese could do little. The following day Nyaunga was captured, and on February 17 the newly motorized 17th Division began to cross the river. Two days later, the 255th Indian Tank Brigade began crossing as well. The race to Meiktila was on.

Kimura did not take the reports of the crossing at Nyaunga too seriously, believing it was the East African troops. Instead, Kimura believed he faced the entire 14th Army crossing near Mandalay. He intended to attack Slim while half his forces were on either side of the Irrawaddy and defeat each component in turn. The Japanese launched fierce counterattacks against the bridgeheads established by the 20th and 19th Divisions.

Although Kimura was playing into Slim’s plan, the British commander had a problem. Slim had requested help from the 36th British Division serving with the NCAC. The request was rejected. Instead, Slim was forced to bring up his reserves, the 5th Indian Division, which caused considerable concern and risk as to whether the overstretched supply line could deal with the extra burden of another division. The matter was resolved “by juggling between formations with the limited transport available and by cruelly overworking the men who drove, flew, sailed, and maintained our transports of all kinds,” wrote Slim.

On February 21, the 17th Division and 255th Tank Brigade began their advances by two routes to Meiktila, which lay about 80 miles away. The columns met light resistance the first day. Tougher resistance was met the next day at the village of Oyin. Two companies of Japanese soldiers from the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Division held 20 bunkers dug underneath houses and screened by snipers along the village approaches. The 6/7th Rajputs supporting the tanks of the 5th Horse quickly came under machine-gun fire, which pinned them down as they advanced into the village.

Allied tanks quickly rumbled into Oyin, blasting at any spotted bunkers. Without warning a Japanese soldier with a bomb strapped to him raced toward the lead tank and threw himself underneath it, detonating the bomb. The explosion knocked out the tank and killed some of its crew. Another enemy soldier climbed aboard a second tank, but the machine gunner in another tank stitched him with bullets before he could pull the string and set off the bomb strapped to his chest. More Japanese tank killers attempted to take out tanks but were unsuccessful. Heavy fighting ensued before Oyin was captured.

On February 23, Slim got terrible news. NCAC had been ordered from northeast Burma to China. With only the 36th British Division left to protect Slim’s left flank, this would free up troops for Kimura to face the XXXIII Corps at Mandalay.

However, Slim was far more concerned with the loss of USAAF air transport needed to transfer the NCAC. Failing to change Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s mind, Mountbatten turned to the British Chiefs of Staff, who pressed the importance of continued USAAF air transport to the U.S. Joint Chiefs. In the end, the United States would not remove any air transport from Slim until June 1 or the 14th Army captured Rangoon, whichever came first. Slim had been ordered in January to take Rangoon after Meiktila had been secured.

Japanese resistance proved weak as the two mechanized brigades of 17th Division pushed on with the 255th Tank Brigade, capturing Kaing and Taungtha. On the afternoon of February 26, the vital airfield at Thabutkon 15 miles north of Meittila was captured. The following day the 17th Division’s 99th Brigade began arriving by air, which would continue until March 2. Armored cars began to probe toward Meiktila.

With news of the capture of the Thabutkon airfield, it became clear to the Japanese high command that this was no raid on Meiktila. Plans for counterattacking across the Irrawaddy were scrapped, and top priority was given to holding Meiktila. Defending Meiktila were three infantry companies made up from communication troops, four airfield defense units, some administration units, and about 500 walking wounded under the command of Maj. Gen. Tomekichi Kasuya. In total, Kasuya had about 4,500 troops to hold the key town. The men wasted no time in building bunkers and planting mines and booby traps. Kimura ordered the 49th Division, which was being held in reserve, to Meiktila. That division’s 1/168th Infantry Regiment arrived in time to help to defend the town, as did an advance party from the rest of the regiment.

The first goal of Maj. Gen. D.T. Cowan, commander of the 17th Indian Division, was to prevent reinforcements from reaching Meiktila by isolating it. On February 28, while the division’s artillery was positioned at Antu to provide supporting fire for the attacking brigades, most of the 63rd Brigade set out on foot for the western edge of Meiktila. By nightfall, the brigade stopped at Kyaukpyugon and set up a roadblock southwest of Meiktila. Meanwhile, the 48th Brigade, which was being led by the 1/7th Gurkha Rifles, reached the Mahlaing/Meiktila Road and headed south on it. At a partly demolished bridge over a watercourse, the column was held up by machine-gun fire. A patrol set out after dark to probe the heavy defenses on the edge of town.

The 255th Tank Brigade swept wide around Meiktila to be in position to attack the town from the east. Leading the way were two reconnaissance columns consisting of a squadron of tanks from the 9th Horse, a troop of armored cars, two platoons of infantry, and a detachment of Royal Engineers. One column reached its objective, the village of Kyigan a couple miles east of Meiktila, while the other column pushed across the main airfield east of town. The latter came under intense fire when it reached the railway line at Khanda, where the enemy had good cover among the trees, shrubs, and buildings. The Japanese position was made more difficult to reach by a canal that ran parallel to the railway line.

The 5th Horse and 6/7th Rajputs attempted to attack on a two-squadron, two-company front. The infantry on the left flank began to take heavy casualties, and a squadron of supporting tanks soon discovered the Japanese had set fire to surrounding fuel drums. As the squadron commander opened his tank hatch to get a better look, he was killed by a sniper. The tanks of the 9th Horse were ordered to a nearby ridgeline near Point 860 to add supporting fire, but with casualties mounting the attack was called off.

On March 1, Cowan’s brigades and the 255th Tank Brigade prepared to fight their way into Meiktila. The terrain did not favor the British tanks. The two lakes north and south of town turned some of the roads into narrow causeways, limiting the Shermans’ maneuverability. Irrigation ditches in the surrounding countryside also hindered tanks. Slim and Messervy flew in to observe the attack.

To the west of Meiktila, the 1/10th Gurkha Rifles of the 63rd Brigade along with a troop of the 5th Horse captured the village of Khanna. They then pushed on toward Meiktila, where they met fierce resistance coming from the hospital where the Japanese had built bunkers. Air strikes were called in, destroying the bunkers and setting the hospital on fire.

To the north, the 1/7th Gurkha Rifles of the 48th Brigade, supported by a couple of squadrons of tanks from the 9th Horse, headed south on the Mandalay Road. In the northern suburbs of Meiktila, it met fierce resistance coming from a monastery that was eventually cleared after hard fighting. As the Gurhkas pushed farther into town they encountered aerial bombs dug into the road and dummy minefields, which consisted of bricks with dirt thrown over them.

The advancing troops also were met with enemy machine-gun fire blazing from the houses and creating deadly crossfires. The houses had to be cleared one at a time in brutal fighting. The troops managed to fight their way to within 100 yards of the railway line that ran through town before the attack was called off and they withdrew for the night at 6 pm.

To the east, the 255th Tank Brigade took Point 860. At that point, the remaining tanks of the 9th Horse, along with 4/4th Bombay Grenadiers and a detachment of the Royal Engineers, pushed east along the railway line into Meiktila. They got within 200 yards of the railway station before being ordered to retire so as not to have any friendly fire incidents with the 48th Brigade.

During the night, the Japanese infiltrated back into the position from which they had been driven the day before. They had to be rooted out again as the 48th Brigade continued its advance into town from the north on March 2. The 4/12th Frontier Force Regiment led the advance supported by two squadrons of the 9th Horse. Overcoming stiff opposition, the troops and tanks got to within 50 yards of the railway line when a well-concealed 75mm gun knocked out three tanks before it was discovered and its crew killed by the infantry.

To the west, 63rd Brigade, which was supported by ground attack aircraft, pushed into Meiktila. Advancing down a causeway, two tanks from the 5th Horse were hit by a 75mm gun sited at the eastern end of the causeway. The attack was redirected south to clear the area along the southern lake. After an artillery barrage crashed down, the 5th Horse pushed through dense thorn thickets and stone buildings.

As the tanks rolled through a belt of thick scrub, they were soon attacked by enemy teams of tank killers throwing gasoline bombs and placing explosive charges under the tracks. Although one tank was disabled, the tank killers were put out of service, and the tanks continued blasting bunkers. Rumbling out of the scrub, the tanks gunned down many of the enemy soldiers withdrawing in front of them.

In the heavy fighting that raged through the afternoon, Naik Fazal Din of the 7/10th Baluch Regiment knocked out a bunker with grenades and then led his section against others. Despite having a ghastly sword wound, Fazal Din ripped the sword from the hands of the Japanese officer who had stabbed him and killed him with it. Then the sword-wielding, mortally wounded Fazal Din killed two other Japanese soldiers and urged his men on before collapsing. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Fighting continued the following day as the 1st Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 48th Brigade and two squadrons of tanks from the 9th Horse pushed into the southeast part of town following an artillery and aerial bombardment. The last Japanese defenders fought fanatically as each bunker, building, and machine-gun nest had to be cleared. Three tanks were knocked out by a 75mm gun in the brutal street fighting.

A badly wounded Lieutenant W.B. Weston was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for setting off a grenade, killing himself and the enemy soldiers in a bunker, thereby saving his platoon from taking casualties. By the end of the day, the last of the Japanese defenders had been killed and Meiktila was in British and Indian hands. While fighting raged in Meiktila, patrols from the 63rd Brigade and 255th Tank Brigade mopped up pockets of resistance on the outskirts of town. The Allies killed approximately 2,000 Japanese soldiers at Meiktila; the rest slipped out during the night.

With a strong enemy force occupying his supply base and blocking his lines of communication, Kimura shifted the 18th Division from the 15th Army (where it had been sent from the 33rd Army to help in the fight around Mandalay) and ordered it to recapture Meiktila. The 18th Division was further strengthened from the 15th Army with two battalions from the 214th Regiment, 33rd Division under its control.

Also heading south was much of the 15th Army’s artillery, consisting of two 150mm howitzers, 21 75mm guns, and 13 antitank guns. The 14th Tank Regiment, which had only nine tanks, was sent along as well. The 119th Regiment of the 53rd Division at Pindale was to cover the 18th Division as it assembled its forces. The 49th Division also was ordered to advance north from Toungoo and assist the 18th Division in retaking Meiktila.

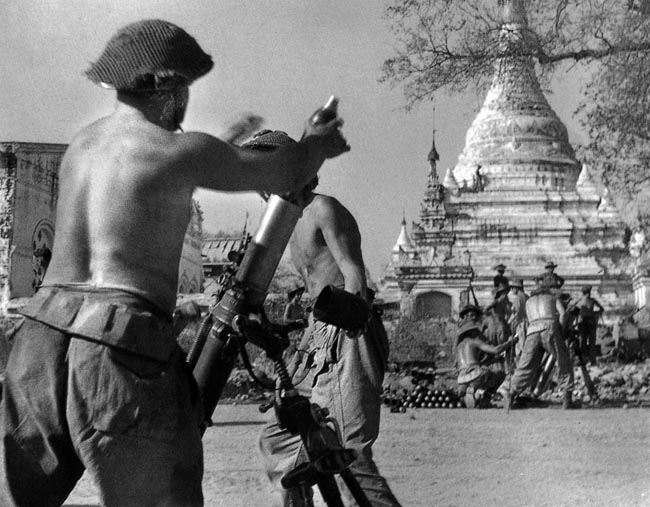

Besides the loss of Meiktila, the situation along the Irrawaddy was deteriorating for Kimura. Rees’s 19th Indian Division was pushing south and by March 8 had taken the large town of Madaya and reached Mandalay Hill. This steep hill, covered with concrete temples and pagodas, was on the outskirts of Mandalay. It was heavily fortified with deep bunkers and honeycombed with machine-gun nests. The 4/4th Gurkhas of the 98th Brigade were given the tough job of taking it. They Gurkhas were reinforced the following day by two companies from the 2nd Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment.

Fighting was fierce as the British and Gurkha soldiers fought their way to the summit of the hill. To get at the Japanese in the deep bunkers, barrels of oil, tar, and gasoline were poured into the access points and ignited with tracer bullets and grenades. On March 11, the hill was taken.

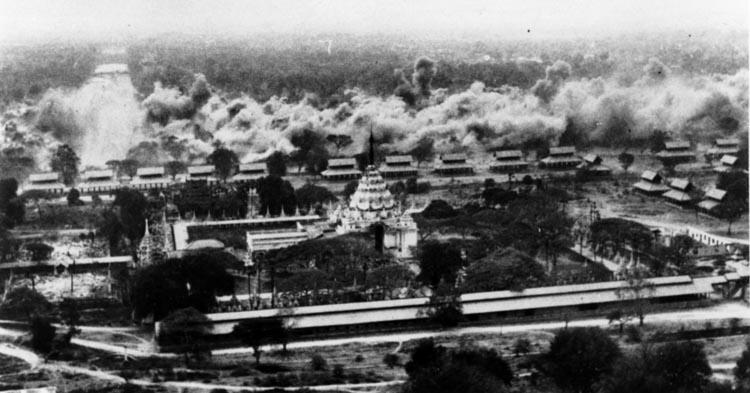

Next lay Fort Dufferin in Mandalay. Surrounded by a wide moat, this impressive fort had brick walls 30 feet wide, tapering to 12 feet at the top and enclosing about 1¼ miles of barracks, offices, and the Royal Palace of Thebaw. Pushing through Mandalay and hammering away at snipers, Rees’s force reached Fort Dufferin by March 15. Probing attacks quickly brought a fierce response from the Japanese defenders. Artillery fire hammered the fort for a couple of days but to little effect. A stealth attack conducted by the 1/15th Punjab and 8/12th Frontier Force of the 64th Brigade also ended in failure in the early morning of March 18.

The RAF hammered the fort, even using a 2,000-pound skipping bomb, which blasted a 15-foot hole in the fort’s wall. Slim, who observed the bombing, thought a direct attack through the breach would be too costly and wanted the fort bypassed. But Rees wanted to try an attack through the sewers into the fort. Neither approach was tried; a white flag and Union Jack appeared in the early afternoon of March 20. A small group of Anglo-Burmese civilian prisoners appeared with news that the Japanese had evacuated the fort through drains the night before. Mandalay was in Allied hands.

Meanwhile, the 2nd British Division, which had crossed the Irrawaddy on February 24 at Ngazun, had broken out from its bridgehead and advanced from the south to meet the 19th Indian Division. The 20th Indian Division pushed south to the Mandalay-Meiktila Road, captured Wundwin, the headquarters of the 18th Division on March 21, and then pushed on to capture Kyaukse, a supply center for the Burma Area Army. The 15th Army was beginning to crumble.

At Meiktila, Cowan ordered the 99th Brigade to defend the town and its airfield, while he sent out columns of tanks, infantry, and artillery backed by air support to disrupt the Japanese forces massing to attack his troops. For nearly a week, the columns inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese and destroyed a number of their guns.

Unable to open a route into Meiktila, the 18th Division now concentrated on the main airfield intending to stop the flow of supplies and starve out the defenders. On the night of March 14, Japanese forces began probing the 99th Brigade defense of the airfield and were beaten back. The next day Japanese artillery began shelling the airfield as the 9th Indian Brigade of the 5th Division was being flown in to reinforce Cowan. While enemy shells were slamming into the airstrip, C-47 transport aircraft were landing. One British soldier recalled the American crew telling him, “We’re not stopping, we’ll land and taxi along, and as we taxi, you lot jump out. As soon as you’re out, we’ll take off again.”

Not long after the arrival of the 9th Brigade, the Japanese shelling of the airfield caused Cowan to order it closed. He then relied on air drops to keep his men partially supplied. In hopes of reversing the situation at Meiktila, Kimura gave the 33rd Army commander, Lt. Gen. Masaki Honda, command of the 18th, 49th, and 53rd Divisions effective March 18. He also ordered the 28th Army to smash the bridgehead at Nyaungu.

Despite suffering personal loss with the death of his son in the fighting at Mandalay, Cowan kept up a steady aggressive defense of Meiktila, sending out columns to clear the nearby villages. With the 9th Brigade taking over the defense of the airfield, the 99th Brigade sent out a column to sweep the villages of Kandaingbauk and Shawbyugan north of Meiktila. The 18th Division was expecting such a move and brought up antitank guns along with three 75mm field artillery pieces and three 75 mm mountain guns to greet the British. The 119th Infantry Regiment was also sent in to reinforce the 55th Infantry Regiment in the area.

The 1st Sikh Light Infantry attacking Kandaingbauk was driven back with heavy casualties, while tanks attempting to attack Shawbyugan had one brewed up and two more knocked out as they moved into the village. A fourth tank became stuck and had to be abandoned. The column withdrew.

While the 18th Division launched heavy attacks against the main airfield, the 49th Division prepared to attack from the southeast against Meiktila. Direct radio contact between the 49th and 18th Divisions was nonexistent, which caused serious problems in coordinating attacks against the British in Meiktila.

Believing the 18th Division controlled the airfield, the 106th Infantry Regiment of the 49th Division launched a heavy attack against the 48th Brigade at Meiktila on the night of March 22. In the bloody fighting, the Japanese pushed up two 75mm guns to the southeast corner of the brigade’s perimeter wire, but to no avail. The attack was broken with almost 200 Japanese killed.

Fighting continued to rage at the airfield. On March 24, the Japanese launched a heavy night attack with infantry and tanks against the 9th Brigade. The assault was beaten back with heavy casualties. The Japanese attacks against the airfield and Meiktila ended in failure. Cowan now began to clear the area and surrounding villages of the enemy.

By that time, it was clear to Honda that he could not continue to fight with the 18th Division, which had lost a third of its troops as casualties. The 49th Division had lost two-thirds of its strength. To the west, the 28th Army had failed in its attempt to smash the bridgehead at Nyaungu. By the end of March, the British 7th Division had cleared a route to Meiktila.

With the 15th Army smashed, its divisions down to less than half strength, most of their guns and trucks lost, and their supply line cut, Kimura ordered his broken forces to retreat south to Toungoo, where he hoped to reorganize and hold southern Burma until the monsoons came. On March 28, Honda and his depleted force were ordered to Pywabe, where they could cover the 15th Army retreat.

Slim wasted no time in pursuing the battered enemy. With the capture of central Burma, Slim pushed south toward Rangoon, hoping to beat the monsoons. The Japanese were unable to stop the 14th Army, but the heavy rains did. The monsoons came two weeks early, slowing the 14th Army down near Prome, about 150 miles north of Rangoon.

Rangoon was captured in early May during a combined airborne and amphibious operation. Although the Japanese retreated to eastern Burma where they would continue to resist until mid-August, their hold on the country had been smashed by Slim between the hammer and the anvil at Mandalay and Meiktila.