By John E. Spindler

In the summer of 2018 a British father and son who were catching crabs along Reculver Beach in Kent stumbled upon a historical item of intense value. What they found was the concrete core from a World War II cylindrical test bomb. Originally encased in steel plating that had long since rusted away, the test bomb was used to hone the skills of the bomber crews who carried out the 1943 mission known as Operation Chastise.

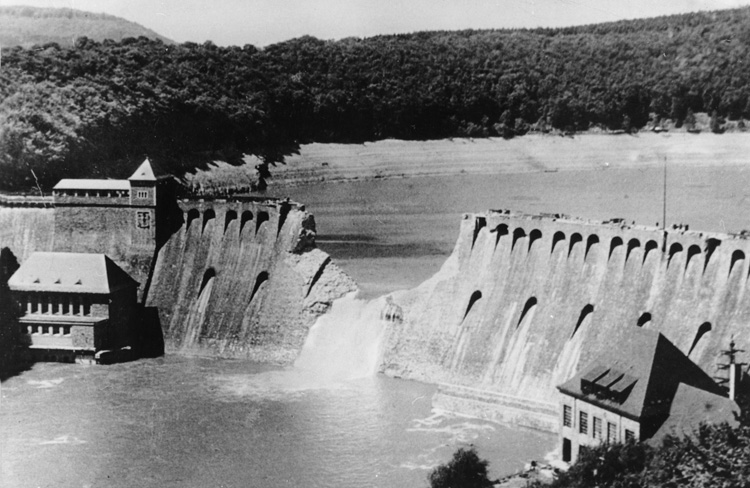

Before the outbreak of World War II, British war planners studied how they might incapacitate Germany’s industrial effort if the United Kingdom went to war again with the European nation. One suggestion was to attack dams in the Ruhr industrial region. The idea was to blow up the dams or strike them with bombs to create breaches that would cause catastrophic flooding.

Unrelated to the British war planning, aircraft designer Barnes Wallis also pondered the issue. By 1941 he calculated that a shockwave would cause the most damage, especially if the bomb detonated underwater against the dam. The problem was the Germans knew their dams were vulnerable to a torpedo attack and had installed antitorpedo nets. Wallis wanted to find a way to deliver an explosive small enough to be carried by an existing Royal Air Force plane, yet be able to evade the antitorpedo defenses and breach the dam.

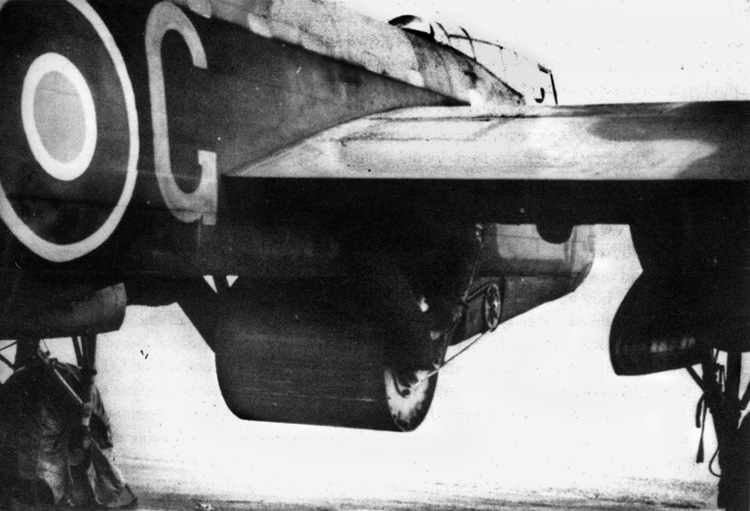

Wallis determined the following year that a bomb skipped across the water’s surface would avoid the nets. Scale tests determined that backspin was critical to ensure successful delivery. His final design consisted of a cylindrical, air-dropped bomb that was 60 inches long with a diameter of 50 inches. The bomb, codenamed Upkeep, weighed 9,250 pounds, of which 6,600 pounds was the Torpex explosive wrapped in a three-eighths-inch steel casing. Three Mark IV hydrostatic pistols were employed to make the bomb explode at a depth of 30 feet.

To prevent the bomb from falling into enemy hands, a self-destruct pistol was installed. Testing in early 1943 showed that the bomb could be carried by the four-engine Avro Lancaster heavy bomber, which by that time had become the backbone of the RAF’s bomber force.

The Lancaster, which was crewed by seven airmen, was one of the most successful bombers in history. Introduced in February 1942, the Lancaster Mark I was powered by four 1,280 horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin XX liquid-cooled V12 engines. This allowed the aircraft to cruise at 200 miles per hour and gave it a range of 2,530 miles. Armed with eight .303-inch machine guns, it could carry a maximum payload of 14,000 pounds in a long, unobstructed bomb bay.

The Lancaster was similar in some general characteristics, such as wingspan and length, and performance characteristics, such as cruise speed, to the main bombers employed by the United States: the Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress and the Consolidated B-24J Liberator. Although the Lancaster had a heavier payload capability, its 21,400-foot service ceiling was significantly less than its counterparts with the Boeing B-17G at 35,600 feet and the North American B-24J Liberator at 28,000 feet.

Once the bomb design was approved, modifications to the Lancaster were needed to carry the weapon. The RAF ordered 30 aircraft but later reduced the number to 21. Designated the Type 464 Provisioning and powered by American-built Packard Merlin 28 engines, the modifications included removal of the bomb bay doors due to the bomb’s size, installation of V-shaped caliper arms to hold the bomb, and Vickers variable-speed hydraulic gear to drive the belt and produce the desired backspin of 500 revolutions per minute. To reduce weight and drag, the mid-upper turret was removed and the hole covered.

With this order, the RAF Operation Chastise into motion on February 28, 1943. The RAF tentatively scheduled the operation between May 14 and May 16 because at that time the water levels in the targeted dam reservoirs would be at their highest. Thus, a breach during that period would cause the greatest possible flood damage.

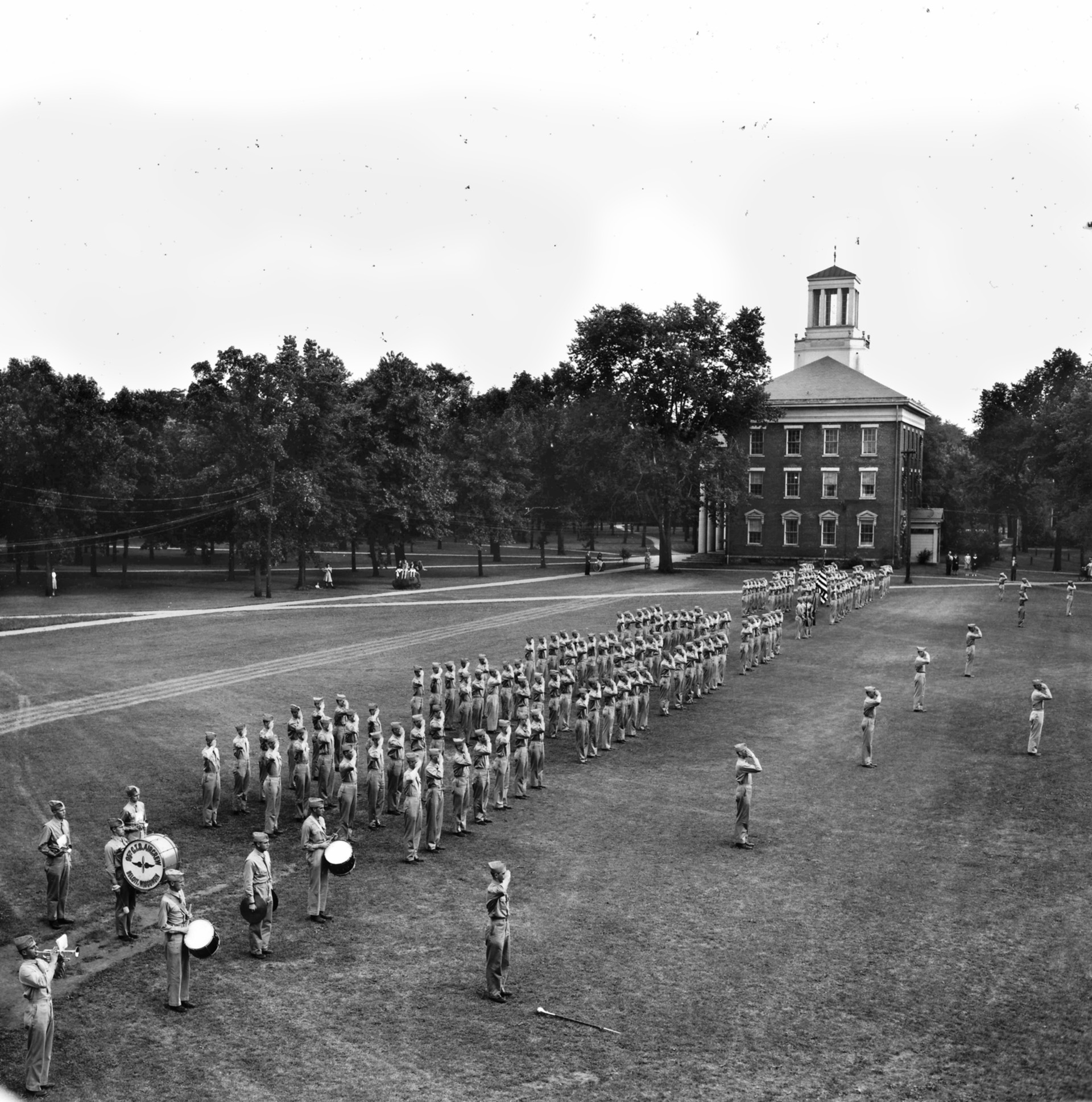

The service selected veteran Wing Commander Guy Gibson to command the new No. 617 Squadron of No. 5 Group. Gibson in turn selected 21 crews from various group squadrons to be based at Scampton in the East Midlands. Gibson informed his men that the mission would be against targets that required proficiency in low-level night flying. The RAF suspended flying regulations in order to improve aircrew efficiency.

Tests using inert bombs allowed Wallis to determine that the bomb needed to be released at a height of 60 feet while flying at 220 miles per hour. No bombsight or altimeter in use by the RAF was accurate enough for such a low-level attack.

Wing Commander Charles Dann solved the bombsight problem. He constructed a hand-held, triangular device made of wood with a sighting hole at the apex. The opposite base had nails in various points that when lined up with the dam’s two sluice towers fixed the release point for the bomb. Determining the 60-foot height took a bit more effort. The result was the employment of two Aldis spotlights. One spotlight was installed in the nose and the other behind the bomb bay. The lights were angled to create a figure eight pattern that could be seen in front of the starboard wing.

Bomb testing began on April 16 at Reculver. By month’s end, the squadron had begun flying the modified Lancasters. Gibson was debriefed in April as to the potential targets in Germany.

The extensive low-level flight-testing revealed that the standard radio sets were not reliable at low altitudes. To remedy the situation, engineers exchanged them for VHF sets. Gibson decided to use only tracer rounds for the Lancaster guns. The highly visible tracer rounds would serve to intimidate German flak gunners more than rounds they could not see. On May 11, No. 617 Squadron dropped inert bombs for the first time. Up until that point, all of the trials had been conducted with test pilots. The first and only test with a live bomb took place two days later.

The weather forecast for the target region during the proposed dates looked favorable. The RAF ultimately decided to proceed with the mission on May 16. Wallis arrived at Scampton to oversee the arming and loading of the weapons into the aircraft. A moment of sheer terror occurred when one of the bombs accidentally fell to the ground while being loaded, but it did not explode.

May 16 proved to be a busy day. Pilots, navigators, and bombardiers met with Gibson and Wallis. Wallis discussed how the bomb worked and what it was expected to accomplish. The main targets were the Mohne, Eder, and Sorpe Dams. Alternate targets were the Lister, Ennepe, and Diemel Dams.

The crews also were debriefed on the different types of dams. For example, Mohne, Eder, Lister, Ennepe, and Diemel were gravity dams constructed of masonry and concrete and held in place by their own weight. To destroy these dams, the bombers were to line up so that their attack runs occurred over the reservoir. In contrast, Sorpe was an earth dam with a central concrete core that was supported on both sides by sloping earthen ramps. To strike Sorpe, Wallis had decided that the bomb would be dropped without spin near the dam’s crest. Instead of flying over the reservoir, the pilots were to fly the length of it.

A final briefing for the crews occurred at 6 pm. The first wave consisted of three flights of three Lancasters taking a southern route. They were to strike Mohne Dam first and then proceed to Eder Dam. If any of the aircraft in the fight still had bombs left, they could strike Sorpe Dam. The commanders in the first flight were Gibson, John Hopgood, and Harold Martin. The pilots in the second flight, which would take a northern route, were Squadron Leader Henry Young, David Maltby, and Dave Shannon. The commanders in the third flight were Squadron Leader Henry Maudslay, William Astell, and Les Knight.

The second wave’s primary target was the Sorpe Dam. Five aircraft departed at one-minute intervals. The commanders were Joe McCarthy, Norman Barlow, Les Munro, Vernon Byers, and Geoff Rice.

The third wave, which was composed of five aircraft, served as a reserve. It departed 90 minutes after the previous wave. The commanders in the third wave were Warner Ottley, Lewis Burpee, Ken Brown, William Townsend, and Cyril Anderson. The RAF planned to radio them their targets during the flight.

At 9 pm on May 16, 1943, the prearranged signal went off and the crews of the first wave boarded their aircraft. McCarthy’s plane developed a mechanical failure, so the crew rushed to the sole backup, which lacked the VHF radio set and Aldis spotlights. Due to their longer route, the second wave left first at 9:28 pm. The first wave departed 11 minutes later. The third wave did not take off until 9 am. the following morning. One aircraft in the wave was downed by enemy antiaircraft fire.

After making a test run, Gibson lined up Mohne Dam and dropped his bomb. After three bounces, it sank and exploded. Unfortunately, the bomb detonated too far from the dam. No breach occurred, but the explosion destroyed the antitorpedo nets. Hopgood’s plane was hit by the dam’s flak guns on his approach, which resulted in the bomb being dropped late. It bounced over the dam and landed near the power station behind the dam. The bomb exploded destroying the power station. Hopgood’s Lancaster caught fire and blew up, but its three crewmen were able to escape. Two survived and were captured.

Martin’s bomb veered too far off center before exploding, leaving Mohne Dam still undamaged. Young’s bomb struck the dam and sank before exploding. Although the bomb hit the target, it appeared not to have caused any damage. Maltby noticed the dam was beginning to crumble when he released his ordnance. After four bounces, the bomb struck the dam and sank before detonating. The resulting explosion, as with the previous four, caused a geyser of water. After ordering Shannon to prepare for his run, Gibson noticed a large amount of water pouring off the other side of the dam. He then spotted a massive hole in the structure. Calling off Shannon, Gibson notified Group 5 that Mohne Dam had been breached. Sending Maltby and Martin home, he ordered the others to follow him to Eder Dam.

Encountering no opposition, the five aircraft reached Eder Dam. It was going to be a difficult approach for the pilots but, fortunately, Eder lacked air defenses. Shannon made a few aborted runs before dropping his bomb. Though it exploded next to the dam, the structure remained intact. Maudslay followed. The bomb was dropped so late that it struck the parapet and detonated, causing severe damage to his aircraft, which was never seen again. Only Knight remained. After an aborted run, he dropped his bomb. It bounced three times, striking the dam slightly to the right of center after which it sank and detonated. After waiting for what seemed like an eternity, Gibson watched Eder Dam break. “[It was] as if a gigantic hand had pushed a hole through cardboard,” he recalled. Gibson notified Group 5 that a breach had occurred at Eder Dam. At that point, the five aircraft turned for home. On the return leg, Young was shot down off the Dutch coast.

The second wave had a more difficult route, having to fly near the heavily defended island of Texel that bristled with antiaircraft guns. Barlow was the first to reach Germany, but his aircraft subsequently disappeared. For unknown reasons, the bomb’s self-destruct mechanism was never armed, and the Germans recovered an intact bomb to study and reverse engineer.

Munro’s Lancaster was struck by flak after crossing Vlieland in northern Holland. The aircraft lost both internal and external communications, as well as power to the tail turret. With no communications and decreased defensive capability, Munro returned to Scampton. His landing was almost disastrous when he cut in front of another returning aircraft. Group 5 lost contact with Byers shortly after takeoff. Drifting too close to Texel, he was downed by flak.

As for Rice, he was flying over the Wadden Sea, an intertidal zone along the coast of Holland, where he and his fellow crewmen were having difficulty judging their altitude. They inadvertently hit the surface of the water. The collision tore off their bomb. Having lost his bomb, Rice turned back to Scampton. McCarthy reached Sorpe but was puzzled to find that there was no sign of an attack in progress. Although visibility was good and there were no enemy air defenses present, he had to make several runs along the dam because of the lack of Aldis spotlights. On his tenth run, McCarthy dropped his bomb, without backspin, along the center of the dam on the water side. It rolled down and exploded. He observed crumbling along the top of the dam but no breach.

As it reached the Continent, the third wave received their targets by radio. Ottley led the wave. Shortly after being directed to Lister Dam, his aircraft was hit by flak. Before the Lancaster exploded, one crewmember escaped and was captured. Burpee strayed too close to the Luftwaffe’s Gilze-Rijen Airbase, and his aircraft was hit by flak. It crashed near the base.

Meanwhile, Brown received instructions to head for Sorpe Dam. After numerous aborted runs, Brown dropped his bomb near the dam’s center. Circling back to check for damage, he saw the top of the dam crumbling over a length greater than when it was struck by Maltby’s bomb.

Townsend received instructions to strike Ennepe Dam, but he had difficulty locating it. He spotted a lake with a spit of land in it. Ennepe Reservoir was supposed to have an island, but the crew concluded they had the correct dam. The bomb exploded short of the parapet without causing any damage. It was later determined that Townsend actually attacked Bever Dam.

Anderson was sent to Diemel then redirected to Sorpe. Already off course due to flak, he encountered a heavy mist across the region. Having trouble getting oriented and with daylight approaching, Anderson aborted the mission and returned to Scampton. Maltby landed the first aircraft to return to Scampton at 3:11 am, and Townsend landed the last one at 6:20 am.

A reconnaissance flight the same day showed massive flooding behind Mohne and Eder Dams. Eighty-seven percent of the water held in Mohne and 75 percent of the Eder reservoir had been released. The flight revealed that power stations, factories, roads, bridges, and pumping stations were destroyed or damaged for miles around. In addition, gas, electricity, and water supplies were severely interrupted. The casualties, the majority of which were foreign workers, totaled 1,341.

Albert Speer, Germany’s minister of armaments and munitions, arrived immediately afterward to determine the extent of the damage. With the approval of German leader Adolf Hitler, 7,000 workers were dispatched to clean up the damage and begin rebuilding the dams. Hitler also approved the transfer of an additional 20,000 workers. Many workers were transferred from Atlantic Wall projects to assist with the dam repairs.

In the aftermath of the strikes, the Germans deployed the equivalent of a division of soldiers to defend the Ruhr dams. They also installed antiaircraft guns at all of the dams.

The effect on the German war effort has been a source of debate among British military experts. Some believed that the heavy losses No. 617 Squadron incurred, which amounted to eight Lancasters and 56 casualties, were in vain given that the Germans had patched up the gaps in Mohne and Eder by October. One postwar analysis estimated that the Germans suffered as little as five percent loss of armament output in the latter half of 1943.

Other military experts hold that the strikes had a positive result largely because of the number of workers and the amount of construction materials the Germans had to commit to rebuild the dams.

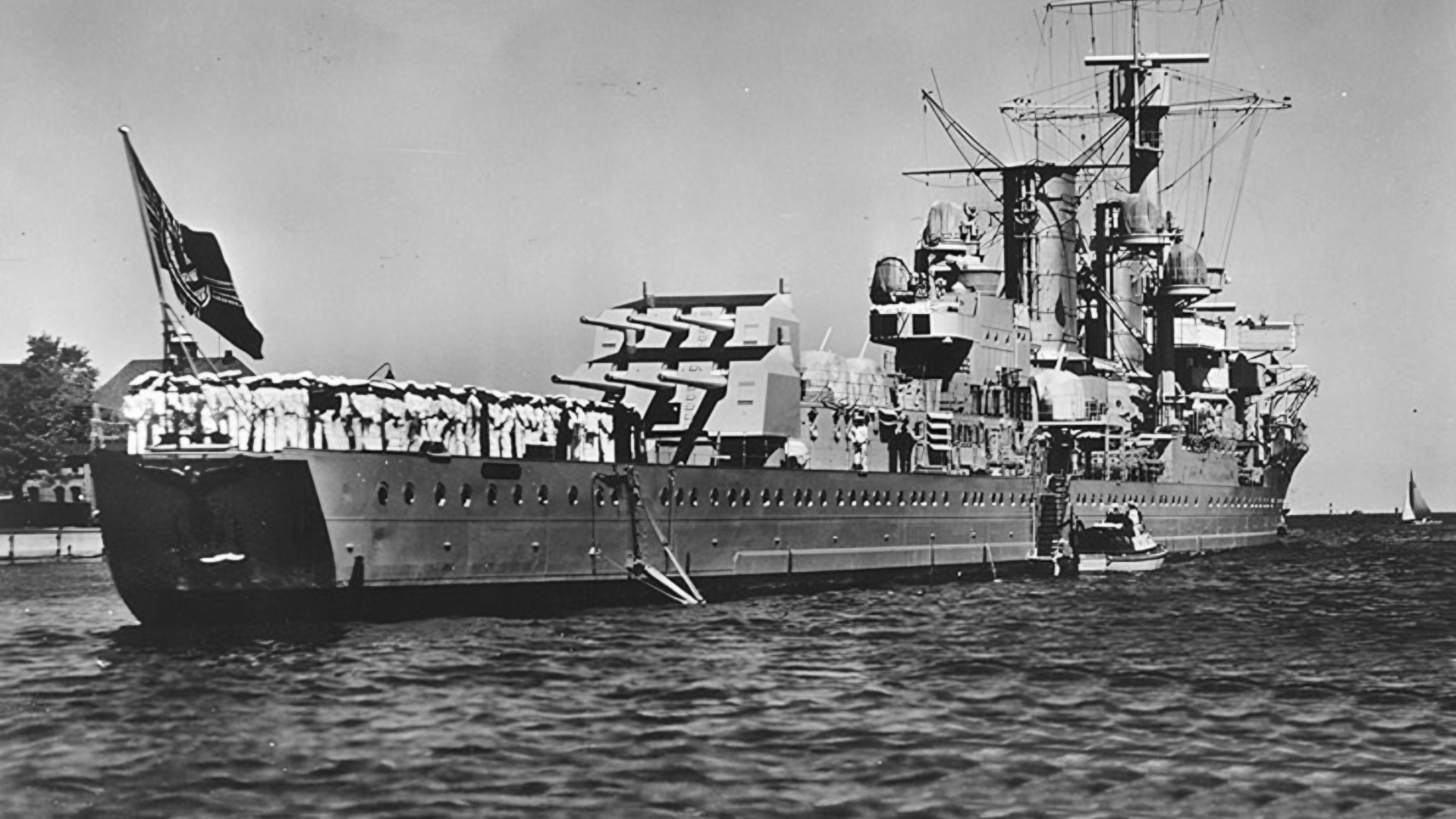

The RAF built on its achievement in Operation Chastise by employing the Lancaster in other critical strikes, such as those against V-weapons sites and the Tirpitz. Although it was a costly mission, in the final analysis Operation Chastise stands as one of the great technological achievements of World War II.