By Richard Camp (Colonel, USMC, ret.)

The island of Tinian is located in the Northern Marianas, three miles southwest of Saipan, 100 miles north of Guam, and 1,500 miles from mainland Japan. A tropical paradise of just 39 square miles, it had been ruled over the centuries by the Spanish and then the Germans. In 1914, the Japanese took it over for agricultural purposes and, in the closing stages of the war, once they realized that it had potential importance as an American air base for the long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers, they began to fortify it.

Today, Tinian is probably best known as the launching site for the American atomic aerial attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But back in July 1944, Tinian was the latest in a string of Pacific islands that formed the American stepping stones to the Japanese home islands.

With the invasion and capture of Saipan well underway, Lt. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, commander of the Expeditionary Force troops, turned his attention to the capture of Tinian.

Garrisoned by 9,000 Japanese troops, Tinian was destined to become, according to Smith, “the most perfect amphibious operation of the Pacific War.” However, the operation would not be without controversy. A long and fractious argument broke out among the senior American leaders concerning which landing beaches should be used.

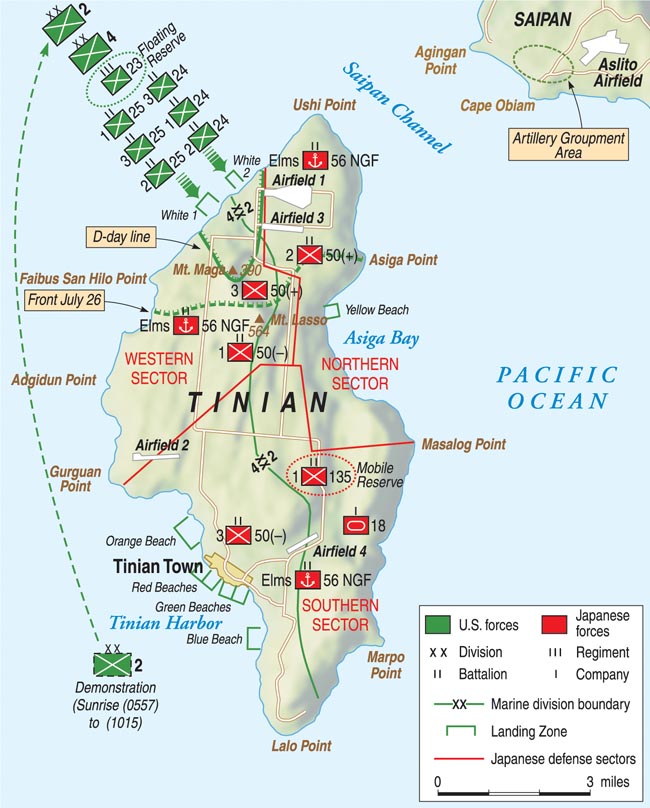

Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly “Terrible” Turner, Joint Expeditionary Force commander, favored landing on Yellow Beach, along the northeast coast. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, Rear Admiral Harry W. “Handsome Harry” Hill, head of the Northern Attack Force, and Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, commanding the Northern Troops and Landing Force, disagreed with Turner’s choice of Yellow Beach and strongly recommended instead two more lightly defended beaches (White 1 and White 2) on the northern end of the island, even though they were both less than 200 yards wide.

Amphibious doctrine called for a beach of no less than 1,000 yards wide to accommodate a division-sized landing. Planners estimated that White Beach 1 would permit eight amphibious tractors to land simultaneously, while White Beach 2 could take 16 at once.

Admiral Hill left the meeting with Turner exasperated. He wrote that Turner “simply would not listen, and again ordered me in very positive terms to stop all White Beach planning and to issue my plan for the Tinian Town landing.”

Terrible Turner’s stance set up a showdown with Howlin’ Mad Smith, who recalled, “Our session on board the [USS] Rocky Mount [ACG-3] generated considerable unprintable language.”

At the heated meeting, Turner roared, “Holland, you are not going to land on the White Beaches. I won’t land you there.”

Smith thundered back, “Oh, yes you will! You’ll land me any goddamned place I tell you to! I’m the one who makes the tactical plans around here! All you have to do is tell me whether or not you can put my troops ashore there!”

Turner was adamant: “I’m telling you now, it can’t be done. It’s absolutely impossible. You can’t possibly land two divisions on those beaches.”

“How do you know it’s impossible?” Smith shot back. “You’re just so goddamned scared that some of your boats will be hurt.”

The argument went on for hours, according to Smith, as each man tried to convince the other of the soundness of his views. Turner contended, “The only feasible beaches are at Tinian Town, and that’s where we are going to land.”

Smith countered forcefully, “If we go ashore at Tinian Town, we’ll have another Tarawa. Sure as hell! The Japs will murder us.”

Smith brought up the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion’s forthcoming recon of the landing beaches. It was like waving a red flag in front of a maddened bull. Turner responded, “They don’t know what to look for. They’re just a bunch of Marines.… People will laugh at you if you keep talking about [the idea]. They’ll think you’re a stupid old bastard.”

Just as fired up, Smith shouted back, “You know goddamned well that it’s my business and none of yours to say where we’ll land. If you say you won’t put us ashore, I’ll fight you all the way.… I’ll take it up with [Admiral Raymond A.] Spruance [commanding the Fifth Fleet], and if necessary with [Admiral Chester] Nimitz [commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet]. Now just put that down in your goddamned book!”

Hill later wrote, “I never saw Kelly [Turner] when he was so mean and cantankerous as on that occasion. He must have been a bit under the weather.”

The meeting finally ended when Smith extracted a promise from Turner to defer a decision on the landing beach until the results of the reconnaissance were in.

Despite the heated argument, Admiral Turner later remarked, “I consider Holland Smith a very fine tactical general and able administrator, and I consider him one of my very best friends.”

General Smith was not so magnanimous. “My plans were challenged by a naval officer who had never commanded troops ashore and failed to understand the principles of land warfare…. Kelly Turner is aggressive, a mass of energy and a relentless taskmaster. The punctilious exterior hides a terrific determination. He can be plain ornery. He wasn’t called ‘Terrible Turner’ without reason.”

Settling the argument would be the Amphibious Reconnaissance Company. It was formed at Camp Elliott, California, in January 1943 under the command of Captain James L. Jones, the father of the future 32nd Commandant of the Marine Corps, General James L. Jones, Jr. In August 1943, the company was redesignated Amphibious Reconnaissance Company, V Amphibious Corps (VAC), Pacific Fleet. At the instigation of Lt. Gen. Smith, the company was expanded into a two-company battalion on April 14, 1944, and designated VAC Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion, Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet.

The VAC Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion, under the command of recently promoted Major James L. Jones, in conjunction with Underwater Demolition Teams 5 and 7, was tasked with performing a night reconnaissance of the Tinian beaches. Their mission was multifaceted. They were to locate obstacles on the beach; determine the height and characteristics of the cliffs and the vegetation behind the beaches; determine the depth of the water and characteristics of the off-lying reef; determine the types of landing craft that could be landed on each particular beach; determine the types of vehicles that could cross the reef and move inland; and estimate whether the infantry could climb the cliffs without using ladders or cargo nets.

Captain Merwin H. “Silver” Silverthorn, Jr.’s Company A and a detachment of “frogmen” from Navy Underwater Demolition Team 7 were assigned to Yellow Beach while 1st Lt. Leo B. Shinn’s Company B and 12 swimmers from Underwater Demolition Team 5, led by the famed frogman Lt. Cmdr. Draper L. Kauffman, were assigned the two White Beaches.

On July 8, the battalion officers and selected noncommissioned officers (NCOs) went aboard USS Gilmer (APD-11), a converted World War I four-stack destroyer transport, and cruised along the west coast of Tinian.

“The purpose of the cruise was to enable us to study the beaches through binoculars and to become familiar with the horizontal silhouette of the island,” Shinn explained, “in order to facilitate our direction during the subsequent reconnaissance.”

The following night, both recon companies, along with swimmers from UDT 7, conducted a rehearsal off the Purple Beaches on Magicienne Bay, Saipan. Shinn said, “It was jointly decided that the UDT would accomplish the hydrographic reconnaissance while the Marines would reconnoiter and secure the information pertaining to the beach proper and the terrain.”

At midnight, the APD stood 3,000 yards offshore and launched 10 black neoprene rubber landing craft (LCRs), which were towed by the ship’s landing craft to a point 1,500 yards off the beach.

“From this point,” Shinn noted, “the LCRs were cautiously paddled to a point 500 yards from shore, at which time the swimmers went into the water.” Each swimmer was equipped with an inflatable CO2 rubber life belt, a flashlight, and a packet of aviator’s yellow emergency dye. “The rehearsal was executed as planned,” Shinn said, “and was completed at about 0500 the following morning.

“The actual reconnaissance of Tinian beaches was ordered for the night of 10-11 July,” Shinn continued. “The entire day was spent in planning the reconnaissance, familiarizing the troops with the plan, and holding debarkation drills and rehearsals. Exhaustive studies were made … of all available aerial photographs, maps, etc., of the beaches.”

The plans called for USS Gilmer and USS Stringham (APD-6) to transport the recon Marines and frogmen to the objective area some 3,000 yards off the beach where they would launch 10-man rubber boats. Ships’ landing craft, with muffled exhausts, would tow the boats approximately 500 yards off their respective beaches. At that point, the boats would be paddled to a point just outside the surf zone.

Admiral Turner was concerned about alerting the Japanese and commented, “The first series of reconnaissances were made as secretly as possible; and, in order to avoid the disclosure of landing intention, positive orders were issued that any mines and obstacles found there were under no circumstances to be disturbed.”

Captain Silverthorn selected 20 swimmers from Company A and eight from Lieutenant Richard F. Burke’s UDT-7 to make the Yellow Beach reconnaissance. At 10:45 pm, under a cloudy sky that obscured the moon, the teams started for the beach.

“When the rubber boats were approximately 500 yards off shore, two sharp reports resembling rifle fire and showing flashes were heard off the south end of the main Yellow Beach,” Major Jones said. “These were followed by two dull reports resembling the noise of mortars.” Under orders to remain covert, Jones ordered the boats to move north “and attempt to obtain hydrographic information from the reef.”

UDT-7 found floating mines in the approaches to the beach and a number of underwater boulders and potholes. On the flanks of the 125-yard-wide beach, swimmers observed almost insurmountable cliffs that were 20 to 25 feet high.

On the beach itself, Marines led by 2nd Lt. Donald F. Neff discovered that the Japanese had strung double-aproned barbed wire. Neff left his men at the high-water mark and, armed only with a knife, he worked his way through the wire to 30 yards inland to locate exit routes. As he crawled along, he could hear nearby Japanese work crews.

At one point, he saw three Japanese sentries peering down from a cliff overlooking the beach. They occasionally shined flashlights onto the beach but failed to spot the Marine officer. Neff found that the Japanese were preparing defenses sited directly at the proposed landing site. After a harrowing time ashore, he returned to his men and swam back to the rubber boat. Neff was later awarded the Silver Star for leading Company A’s recon team that night.

Based on the reconnaissance, the commander of Task Force 52 stated: “Yellow Beach was found to have fairly heavy surf, and [was] unsuitable for a large body of troops because of the steep cliffs and narrow exits.” The landing, it was decided, would come only at White Beaches 1 and 2. Shinn split his company into two teams, one for White Beach 1 (the northernmost beach) and the other team for White Beach 2.

“The beaches were about 60 yards and 160 yards,” recalled Brig. Gen. Russell E. Corey, who was a lieutenant at the time. The two were separated by 1,000 yards of rocky coast. At 11:30 pm, the two Marine teams disembarked from Gilmer.

“Debarkation went well until the LCRs were cast off from their tows,” Shinn said. A strong tidal current carried both teams north. The White Beach 1 team landed on a coral outcropping about 800 yards north of Tinian and never got ashore. If not for the coral outcrop, they would have been carried even farther into the Saipan Channel.

The White Beach 2 team landed on White Beach 1 and made a hasty reconnaissance of the beach and its approaches. Meanwhile, the UDT swimmers scanned the water offshore, but did not find anything that would interfere with a landing.

One group of frogmen, led by Lieutenant (j.g.) George Suhrland, crawled onto the beach above the high-water mark to check out a report that mines had been planted, but he found no explosives.

During the recovery, the northerly current, plus low scudding clouds and a light fog, made it extremely difficult to locate the rubber boats. Gunnery Sergeant Sam Lanford, Pfc. John Sebern, and Lt. Cmdr. Kauffman, the UDT commander, missed the recovery and were swept into the channel that separated Tinian from Saipan. They had to tread water for several hours before finally being rescued by USS Dickerson (APD-21), a picket boat patrolling the channel. Fortunately, the men had stuffed flotation bladders in their jackets, which helped keep them afloat.

With only half the mission accomplished, Jones assigned Silverthorn’s Company A to recon White Beach 2 the next night. “Arrangements were made to use the USS Stringham to land the troops and to use the USS Gilmer to pick them up,” Jones explained. “Five rubber boats with swimmers and paddlers and one drone rubber boat carrying a mounted tripod wrapped with wire mesh were towed to a point 1,900 yards off White Beach 2.”

Jones blamed “the failure on the first night to a lack of surface radar on the Gilmer to guide the boats to the beach,” thus the improvised radar reflector. Company B furnished and manned the boats while Silverthorn supplied six two-man swimmer teams of one officer and one senior staff NCO. Twelve UDT swimmers also accompanied the recon team.

“At 1,900 yards,” Jones said, “the rubber boats cast off and the ship guided them by radio. All the men in the LCRs had steel helmets and, together with the wire-mesh tripod, enabled the ship to guide the boats to a point 400 yards to seaward and 100 yards south of White Beach 2.”

At that point, all the swimmer teams slipped into the water and made their way toward the beach, using either the sidestroke or the breaststroke to keep from splashing or making noise. They were almost invisible; only their heads were above water, and they had darkened their faces and necks with camouflage paint. The water over the reef was deep enough for the men to traverse without exposing themselves to observation, although several swimmers were cut by the sharp coral.

Once ashore, the recon Marines quickly determined that there were no obstacles on the beach, nor any evidence of Japanese activity. While the Marines worked the beach, the UDT scanned the water and the reef fronting the shoreline. At one point, a Japanese sentry almost stepped on two team members as they lay exposed on the sand, but they were not discovered.

Silverthorn noted, “A very thorough reconnaissance of the surf conditions, reef, beach, and flanks was done.” The teams completed their assignments and returned to the recovery ships on time. Silverthorn then briefed Rear Admiral Hill on the results of the reconnaissance: “Admiral, the beaches are narrow [but] there are no mines, no coral heads, no boulders, no wire, no boat obstacles, and no offshore reefs. The beaches are as flat as a billiard table!”

That sold Hill. He acknowledged, “You have convinced me.” For his leadership, Silverthorn was also awarded the Silver Star.

The landing force operations officer summarized the work and results of the amphibious reconnaissance: “This was an extremely difficult operation that was almost perfectly executed, and the perfection of the execution is due both to the high competence of the reconnaissance battalion and the underwater demolition team….”

Rear Admiral Hill, having been forcefully rebuffed by Vice Admiral Turner, kicked the beach decision up to Admiral Spruance, who called a meeting of the primary commanders on the afternoon of July 12. Lt. Gen. Smith and Rear Admiral Hill strongly argued the case for the White Beaches. At the conclusion of the presentation, Turner calmly and nonchalantly announced that he would accept the plan.

A participant later wrote, “We were all surprised at the unexpected rapidity and ease with which the plan was presented and accepted.” Hill noted, “What a great relief that was for us all.” Turner remarked, “Before the reconnaissance … I had tentatively decided to accept the White Beaches unless the reconnaissance reports were decidedly unfavorable.”

July 24, 1944.

Turner shrugged off criticism of his early intransigence. “I merely insisted that full study and consideration be given, before decision, to all possible landing places … all of them difficult for more than one reason. And, in accordance with an invariable custom, I refused to give a decision until such studies had been made, and also until the main features of the landing plan had been developed.”

On July 24, the assault elements of Maj. Gen. Clifton Cates’ 4th Marine Division landed successfully across the White Beaches with minimum casualties by mid-afternoon. The next day, the 2nd Marine Division came ashore over the same beaches. Both divisions had suffered heavy casualties during the Saipan operation and were not eager for another slugging match.

The 2nd Marine Division had been especially hard hit over the last 18 months, beginning with Guadalcanal where it had suffered 1,000 casualties, while an additional 12,000 men had come down with malaria. Nine months later, the division had gone through hell at Tarawa, where it had lost 3,200 men, including nearly 1,000 dead. A third island invasion—at Saipan in June and July 1944—ended in victory but also with another 1,300 Marines killed and 5,000 wounded. About 29,000 Japanese troops died.

The 4th Marine Division was relatively new but had been blooded at Roi-Namur in the Marshall Islands in January and February 1944, where it suffered moderate casualties—fewer than 800 men. During the Battle of Saipan, it lost 6,000, including about 1,000 dead. The Tinian landing would be its third in a little over six months and would be the first under a new divisional commander—Maj. Gen. Cates.

The 4th Division’s battalions were seriously understrength; they had been depleted at Saipan, and their average strength was now down from 880 men to just 565 men—a drop of more than 35 percent.

Writing in the official history of the battle, Major Carl W. Hoffman noted, “The morale of the troops committed to the Tinian operation was generally high. This fact takes on significance only when it is recalled that the Marines involved had just survived a bitter 25-day struggle and that, with only a fortnight lapse (as distinguished from a fortnight rest), they were again to assault enemy-held shores…. [Their] spirit … was revealed more in a philosophical shrug, accompanied with a ‘here-we-go-again’ remark, than in a resentful complaint [at] being called upon again so soon.”

Admiral Turner said he wanted the Marines to secure the island in two weeks. Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, who relieved Lt. Gen. Holland Smith as V Amphibious Corps commander, said he would get it done within 10 days. It would actually take only nine.

To lessen the anxiety of the Marines going ashore and to confuse the Japanese as to the actual location of the landings, Rear Admiral Hill divided the island into five fire support sectors and ordered a heavy naval bombardment for each one.

Tinian Town was hit the hardest. Doing the damage were the battleships California, Tennessee (both damaged at Pearl Harbor), and Colorado, along with the cruisers Cleveland and Louisville and seven destroyers. The Colorado’s 16-inch guns knocked out two 6-inch coastal defense guns at Faibus San Hilo Point that could have disrupted the landing on White 1 and 2 Beaches. The Japanese fired back, hitting the Colorado 22 times and killing 43 sailors and wounding 198. The Tennessee came in later to finish off the coastal defenses.

Naval barrages were suspended three times on J-day (Jig being the equivalent of D-day for the Tinian operation) to allow American air power to pound roads, railroad junctions, pillboxes, gun emplacements, and the beaches at Tinian Town. More than 350 Navy and Army planes took part, dropping 500 bombs, 200 rockets, 42 incendiary clusters, and 34 napalm bombs.

After the softening up had ended, the 4th Marine Division transferred to 37 LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) at anchor off Saipan. They were issued rations for three days, water, medical supplies, and ammunition; vehicles and other equipment had been preloaded, beginning on July 15. As one historian wrote, “The troops were going to travel light: a spoon, a pair of socks, insect repellant, and emergency supplies in their pockets, and no pack on their backs.”

On Jig Day—July 24—the 4th Marine Division, designated the assault division, headed for Tinian. Because the beaches were not wide enough to accommodate battalions landing abreast, the assault troops would land by columns—squads, platoons, and companies.

Two regiments of Maj. Gen. Thomas E. (“Terrible Tommy”) Watson’s 2nd Marine Division made a diversionary feint against Tinian Town, hoping to tie down Japanese forces there, before it made the actual landing, along with the third regiment, on the lightly defended northwestern beaches.

The feint, made by Marines in 22 LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel) served to freeze in place around Tinian Town a whole battalion of the Japanese 50th Infantry Regiment and various elements of the 56th Naval Guard Force. The Japanese commander, Colonel Kiyochi Ogata, was convinced that he had repelled an invasion, and he sent a message to Tokyo that his forces had turned back 100 landing barges.

While he was bragging about his accomplishment, however, the 24th Marine Regiment was hitting White Beach 1 in two dozen LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked—sometimes called “amtracs” or “alligators”), while the 25th Marine Regiment was coming ashore at White Beach 2. By 8:20 am, the 24th’s entire 2nd Battalion was ashore. On the 26-minute run-in to the beaches, the troop-laden LVTs took scattered and ineffectual rifle and machine-gun fire while support craft saturated the beaches with rockets and cannon fire.

At White Beach 1, the first wave of 24th Marines to land was taken under fire by a small detachment of defenders holed up in caves and crevices, but these enemy troops were quickly silenced. Within an hour, the entire 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 24th were ashore on White 1 and were preparing to move inland. Although sporadic artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire hit the 2nd Battalion, it did not stop the advance, and the unit reached the western edge of Airfield No. 3 and cut the main road linking Airfield No. 1 with the east coast and southern Tinian by 4 pm.

On the left of the 2nd Battalion, the 1st Battalion ran into heavier resistance, with defenders firing from caves. Flame-throwing tanks were called up, but the stubborn Japanese refused to yield. To fill a gap that developed between the 1st and 2nd Battalions, the 24th’s 3rd Battalion, in reserve at the beach, was brought up.

At White Beach 2, the 25th Marine Regiment landed in the midst of a thick minefield that had gone undetected; three LVTs and a jeep were blown up. It took six hours to neutralize the mines. The defenders had also cleverly booby-trapped cases of beer and other “souvenirs” with explosives that killed or maimed unwary Marines.

As they pushed farther inland, the Marines also encountered 50th Regiment troops—well entrenched in caves, pillboxes, and ravines—who fought back with machine guns, mortars, and antitank and antiboat guns. The Marines decided to bypass them and leave them for later waves to eliminate. Harassing fire was also coming from Japanese artillery on Mount Lasso, two-and-a-half miles away, where Ogata had his headquarters.

The 3d Battalion/25th Marines’ commander, Lt. Col. Justice M. “Jumping Joe” Chambers, recalled considerable confusion on the beach, “the confusion you [always] get when you land, of getting the organization together again.”

By sundown, the two regiments had formed a crescent-shaped beachhead 3,000 yards wide at the shoreline and bulging inland 1,500 yards, digging in to see what the enemy would throw at them during the night.

The 23rd Marine Regiment, in 4th Division reserve, had the hardest time on Jig Day, but not from the enemy. After being held for most of the day on LSTs, they were finally ordered to climb into landing craft and head for shore, landing at 2 pm. The regimental commander, Colonel Louis R. Jones, ran into serious communication problems and found himself out of contact with his division and his battalions for hours. To compound his problems, the engine of the LVT in which he was riding malfunctioned, and it took him and his staff seven hours to get ashore.

Otherwise, the operation had gone off relatively smoothly. More than 15,000 Marines were ashore plus four battalions of artillery, two dozen half-tracks mounting 75mm guns, 48 medium Sherman tanks, and 15 flame-throwing tanks. Although some battalions had failed to reach their first-day objectives, the beachhead extended nearly a mile inland. Marine casualties had been light—15 dead, 225 wounded—while the Japanese had lost 438. On the whole, as one historian put it, “It had not been a bad day’s work.”

Occupying the northern half of the defensive crescent were the 24th Marines, backed up by the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines. The 25th and a battalion of the 23nd occupied the southern half, with the remainder of the 23rd in reserve. On the beaches in the rear, artillery battalions from the 10th and 14th Marines, engineer battalions, and other special troops were on alert.

And alert they needed to be. The Japanese were not known for giving up even when faced with impossible odds. The American commanders knew they were in for a fight. And it would begin after dark at the end of Jig Day.

True to form, the Japanese were preparing to strike back. Because the American bombardment had destroyed his ability to communicate with his units, Colonel Ogata counted on each unit on Tinian to be responsible for its own counterattack. In case of such an American landing, he had given an order the previous month to “destroy the enemy on the beaches with one blow, especially where time prevents quick movement of forces within the island.”

Outnumbered, and without hope of reinforcement or evacuation, Ogata’s forces probably knew they were doomed. But they vowed that they would give a good account of themselves before they were killed. The Emperor would be proud of them.

The counterattack began at 10:30 pm when the Japanese Mobile Counterattack Force, a 900-man battalion of the 135th Infantry Regiment equipped with rifles and demolition charges, began probing the center of the Marine line where the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 24th Marines were dug in.

When the presence of the advance elements was detected, the Marines called in the artillery. Lt. Col. Chambers, the 3rd Battalion/25th Marines’ commander, later wrote, “There was a big gully that ran from the southeast to northwest and right into the western edge of our area. Anybody in their right mind could have figured that if there was to be any counterattack, that gully would be used.

“During the night … my men were reporting that they were hearing a lot of Japanese chattering down in the gully…. They hit us about midnight in K Company’s area. They hauled by hand a couple of 75mm howitzers with them and when they got them up to where they could fire at us, they hit us very hard. I think K Company did a pretty damn good job but … about 150-200 Japs managed to push through [the 1,500 yards] to the beach area….

“When the Japs hit the rear areas, all the artillery and machine guns started shooting like hell. Their fire was coming from the rear and grazing right up over our heads…. In the meantime, the enemy that hit L Company was putting up a hell of a fight within 75 yards of where I was and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it.”

Chambers continued, “Over in K Company’s area was where the attack really developed. That’s where [Lieutenant] Mickey McGuire had his 37mm guns on the left flank and was firing canister [antipersonnel shells filled with large pellets for close-in fighting]. Two of my men [Corporal Alfred J. Daigle and Pfc. Orville H. Showers] were manning a machine gun…. These two lads laid out in front of their machine gun a cone of Jap bodies. There was a dead Jap officer in with them. Both of the boys were dead.”

In describing this action, a Marine combat correspondent wrote, “[Showers and Daigle] held their fire until the Japanese were 100 yards away, then opened up. The Japanese charged, screaming, ‘Banzai,’ firing light machine guns and throwing hand grenades. It seemed impossible that the two Marines—far ahead of their own lines—could hold on…. The next morning they were found slumped over their weapons, dead. No less than 251 Japanese bodies were piled in front of them.” The Navy Cross was awarded posthumously to Daigle and the Silver Star posthumously to Showers.

Just before daybreak, two tank companies, commanded by Major Robert I. Neiman, showed up, itching for a fight; Lt. Col. Chambers sent them off to an area held by Companies K and L. Neiman returned a half hour later and said, “You don’t need tanks. You need undertakers. I never saw so many dead Japs.”

The 75mm pack howitzer gunners of Battery D, 14th Marines also did their part to break up the enemy attacks, and the .50-caliber machine guns of Batteries E and F “literally tore the Japanese … to pieces,” according to one report. Altogether, about 600 Japanese were killed in their attack on the center of the Marine line.

On the left flank about 600 Special Naval Landing Force troops from the Ushi Point airfields attacked the 1st Battalion, 24th Marines at 2 am. Company A was hit so hard that it had only 30 men still capable of fighting and was forced to draw reinforcements from engineers, corpsmen, communicators, and members of the shore party. Illumination flares lit up the battlefield, allowing the Marines to mow down the attackers with 37mm canister shells, machine guns, rifles, and mortars.

Still, the fight went on until, at dawn, Shermans from the 4th Tank Battalion arrived to sweep the enemy from the field. At dawn, 476 Japanese bodies were found sprawled, most of them in front of Company A’s position. Realizing their cause was lost, many Japanese began using their grenades to commit suicide.

The Japanese had only 12 tanks on Tinian, and they used half that force in an attack beginning at 3:30 am on the 25th. Trying to dislodge the 23rd Marines north of Tinian Town, they rolled into a storm of lead and steel from massed Marine artillery, antitank guns, bazookas, machine guns, and rifles and were turned into smoldering junk.

A reporter recounted, “The three lead tanks broke through our wall of fire. One began to glow blood-red, turned crazily on its tracks, and careened into a ditch. A second, mortally wounded, turned its machine guns on its tormentors, firing into the ditches in a last desperate effort to fight its way free. One hundred yards more and it stopped dead in its tracks. The third tried frantically to turn and then retreat, but our men closed in, literally blasting it apart….

“Bazookas knocked out a fourth tank with a direct hit which killed the driver. The rest of the crew piled out of the turret screaming. The fifth tank, completely surrounded, attempted to flee. Bazookas made short work of it. Another hit set it afire and its crew was cremated.” The sixth tank was able to flee the scene.

Although their tank support was gone, elements of the 50th Regiment continued to attack the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Marines, but were torn to pieces by 37mm antitank guns using canister shot. Still, the battle raged on, with small groups continuing to desperately throw themselves against Marine positions without success.

When dawn broke on July 25, a total of 1,241 Japanese bodies carpeted the battlefield, and it is believed that hundreds more were carried away by their comrades; fewer than 100 Marines were wounded or killed. Although it was only the second day since the landings, the Japanese defense was essentially broken. Without communications, Colonel Ogata had lost control of his forces—and, hence, the battle. Now it was just a matter of time before Tinian was secured. Scattered pockets of resistance, however, would still have to be overcome.

A Marine historian wrote, “Now and again during the next seven days, small groups took advantage of the darkness to [launch night attacks], but for the most part they simply withdrew in no particular order until there remained nowhere to withdraw.”

From White Beaches 1 and 2, the two Marine divisions pressed steadily southward, crushing enemy positions, pushing the Japanese before them, and standing fast whenever a group of Ogata’s men launched a suicidal banzai attack or tried to infiltrate Marine positions in the dark.

The 4th Division’s intelligence officer, Lt. Col. Gooderham McCormick, said his division still expected a massive, coordinated counterattack: “We still believed the enemy capable of a harder fight … and from day to day during our advance expected a bitter fight that never materialized.”

Lieutenant Colonel William W. Buchanan was the assistant naval gunfire officer for the 4th Division at Tinian. He recalled, “We used the same tactics on Tinian that we did on Saipan: that is, a hand-holding, linear operation, like a bunch of brush-beaters, people shooting grouse or something, the idea being to flush out every man consistently as we go down, rather than driving down the main road…. But this was the easiest thing and the safest thing to do. And who can criticize it? It was successful. Here, again, what little resistance was left was pushed into the end of the island … and quickly collapsed.”

The “brush beating” or “grouse hunting” was anything but easy. The oppressive heat and humidity and drenching monsoon rains exhausted the Marines, and there was the ever-present danger of mines, booby traps, a sniper in a tree, or a sudden ambush from out of the jungle.

To assist the 4th Division in the mopping-up operation, Maj. Gen. Watson’s 2nd Marine Division moved in. On July 26, the 2nd captured the Ushi Point airfields in the north then turned south. Two days later the Seabees had the Ushi Point fields in operation for Army P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. Also on the 26th, the 4th Division climbed Mount Maga in the center of the island and forced Colonel Ogata and his staff to abandon their command post on Mount Lasso, which fell to the Marines with barely a shot being fired.

With the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions in a skirmish line of divisions abreast from one side of the island to the other, the sweep southward began on July 27. Little resistance was encountered, and casualties were light. The next day the Gurguan Point airfield fell to the advancing Marines’ 4th Tank Battalion.

After the battle, Maj. Gen. Cates was asked how he spurred on his 4th Division troops. He said he told them, “Now, look here men, the [Hawaiian] island of Maui is waiting for us. See those ships out there? The quicker you get this over with, the quicker we’ll be back there.’ They almost ran over that island.”

The southward drive was picking up steam. In fact, the usual preparatory artillery barrages fired from guns on Saipan were canceled to save the diminishing stocks of ammunition. It was pointless to waste ammunition on areas that had been abandoned by the enemy.

By nightfall on the 29th, the Marines controlled the northern half of the island. As the 4th Marine Division closed in on Tinian Town, more determined pockets of resistance were encountered, and torrential rain came down in sheets. Japanese mortars and artillery also rained down, accompanied by an enemy ground probe against the 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines; it was beaten back.

The next day, Colonel Franklin A. Hart’s 24th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division was given the task of taking Tinian Town. They were assisted by the division’s artillery battalions plus the offshore fire of cruisers and destroyers. When the supporting fires lifted, the 24th’s 1st Battalion moved out, only to be hit by heavy fire coming from caves along the town’s north coast. This was quickly squelched by flame-throwing tanks. Engineers then sealed the mouths of the caves with explosives.

Tinian Town was mostly a rubble-filled ghost town by the time the 24th Marine Regiment entered it shortly after 2 pm on the 30th. About this same time, the 25th Marines, after swatting away some pesky small-arms fire, were busy seizing Airfield Number 4 on the town’s eastern edge; a lone Zero fighter was found parked on the crushed coral airstrip. That night the 24th Marines were relieved by units of the 23rd Marines and the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines.

To the east, the 2nd Marine Division was making good progress until it ran into some opposition. This was soon overcome when elements of the division chased an enemy force into a large cave where, with the help of a flame-throwing tank, 89 Japanese died and four machine guns were destroyed. By 6:30 pm, the 2nd Marines had achieved their day’s objectives and buttoned up for the night. About 80 percent of the island was now in American hands. It was time for the final push.

Major General Schmidt, commander of the Marine force on Tinian, issued an order late on the afternoon of July 30 calling on the two divisions to drive all the way to the southeast coastline, seize all territory remaining in enemy hands, and “annihilate the opposing Japanese.” It was an order easier to give than execute. Waiting in caves and on rugged terrain of cliffs and a plateau were about 500 troops of the 56th Naval Guard Force and up to 1,800 troops of the 50th Infantry Regiment in the southeastern corner of the island. They were ready and willing to die for their emperor in their last redoubt.

To soften up the enemy before the assault, the Marines called upon all their artillery on the island, plus the XXIV Corps Artillery on southern Saipan, to bombard the enemy positions throughout the night of July 30-31. The next morning, the battleships Tennessee and California and the cruisers Louisville, Montpelier, and Birmingham added their voices for a 75-minute bombardment, pausing long enough to allow a 40-minute strike on the enemy’s positions by 126 P-47s, B-25 bombers, and carrier-based TBF Avenger torpedo bombers.

A Marine historian noted, “The planes dropped 69 tons of explosives before the offshore gunfire resumed for another 35 minutes. All told, the battleships and cruisers fired approximately 615 tons of shells at their targets. Artillerymen of the 10th Marines fired about 5,000 rounds during the night; 14th Marines gunners fired 2,000. The effect, one prisoner said, was ‘almost unbearable.’”

The Japanese defensive position was almost ideal. As Marines tried to scale the cliffs and steep slopes of the plateau, they were met by concentrated small-arms and mortar fire. Tanks had trouble negotiating the thick vegetation and minefields and could not climb the trackless slopes. To suppress enemy fire along the beach, the guns of armored amphibians patrolling the coastline were brought into play. At about 10 am, a platoon-sized Japanese beach unit launched a suicidal counterattack against the 1st Battalion, 24th Marines and was annihilated.

The 1st Battalion, 23rd Marines also ran into stubborn opposition, including a hidden, high-caliber weapon that forced them to ground. Sherman tanks were brought up and quickly dispatched the weapon. A well-camouflaged concrete bunker was also discovered, and the 20 troops inside were all killed.

In another section of the battlefield, the Japanese seized a disabled Sherman and used it as an armored machine-gun nest until another American tank destroyed it.

Late in the afternoon, the 1st Battalion, 23rd Marines and a company from the 2nd Battalion finally managed to reach the top of the plateau as other battalions surrounded the base and began scaling the sides. The 1st Battalion, 8th Marines made it to the top by late afternoon, followed by elements of the 2nd Battalion. There they stayed for the night.

Captain Carl W. Hoffman, a company commander, recalled his experiences on top of the plateau the night of July 31: “By the time we got up there … there wasn’t enough daylight left to get ourselves properly barbed-wired in, to get our fields of fire established, to site our interlocking bands of machine gun fire—all the things that should be done in preparing a good defense.

“By dusk, the enemy commenced a series of probing attacks. Some Japanese intruded into our positions. It was a completely black night. So, with Japanese moving around in our positions, our troops became very edgy and were challenging everybody in sight. We didn’t have any unfortunate incidents of Marines firing on Marines … [because they] were well-seasoned by this point….

“As the night wore on, the intensity of enemy attacks started to build and build and build. They finally launched a full-scale banzai attack against [our] battalion…. The strange thing the Japanese did here was that they executed one wave of attack after another against a 37mm position firing canister ammunition….

“That gun just stacked up dead Japanese…. As soon as one Marine gunner would drop, another would take his place. Soon we were nearly shoulder-high with dead Japanese in front of that weapon…. By morning we had defeated the enemy. Around us were lots of dead ones, hundreds of them as a matter of fact.”

Captain Hoffman was a trumpet player and had carried his horn with him throughout the Pacific War. When the fighting died down on top of the plateau, he took the instrument out and began playing some tunes to soothe everyone’s nerves. “My Marines were shouting in requests: ‘Oh, You Beautiful Doll’ and ‘Pretty Baby’ and others.

“While I was playing these tunes, all of a sudden we heard this scream of ‘Banzai!’ An individual Japanese soldier was charging right toward me and right toward the barbed wire. The Marines had their weapons ready and he must have been hit from 14 different directions at once. He didn’t get to throw [his] grenade…. I’ve always cited him as the individual who didn’t like my music. He was no supporter of my trumpet playing. But … I even continued my little concert after we had accounted for him.”

For the next two days, the Japanese continued to mount attacks against the Marines, and although they managed to inflict some casualties, they were slaughtered en masse in the effort. At 6:55 pm on August 1 (the day Ogata committed suicide), General Schmidt declared Tinian “secured,” but a few of the Japanese holdouts didn’t get the word. For the next few months, isolated pockets of the enemy continued to charge the American lines or refused to come out of their hiding places. In fact, the last holdout on Tinian, Murata Susumu, was not discovered until 1953. He was not a soldier but a Japanese civilian working for NKK, the largest sugar company in the Marianas.

It wasn’t only the Japanese who were hiding in caves. As many as 10,000 of the island’s civilians had also sought shelter in them to avoid the fighting and were now beginning to emerge, uncertain of what would happen to them. It is estimated that about 4,000 civilians had been killed in the battle for Tinian.

On nearby Saipan, Marines had watched in helpless horror as civilians, fearful that the Marines would torture and kill them, threw themselves off cliffs. Fortunately, such mass suicides were rare on Tinian, but some civilians were accidently shot dead when they wandered into Marine lines at night. The remaining Japanese also attached explosive charges to groups of civilians and forced them to run at the Americans. Japanese soldiers also pushed some civilians off cliffs.

Keeping his promise to his men, Maj. Gen. Cates’ entire 4th Marine Division sailed on August 14 to its base camp on Maui. During the Tinian operation, it had suffered more than 1,100 casualties, including 212 killed; its next assignment would be Iwo Jima. The 2nd Marine Division, which counted 105 killed and 655 wounded, would remain in the Marianas until the war’s end. It is estimated that virtually all of the 9,000 Japanese soldiers who had defended Tinian were killed, with fewer than 400 being taken prisoner.

Thanks to the work of the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion, 42,000 men and their equipment had been landed across the narrow White Beaches in what Admiral Spruance declared was “the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation in World War II.” Smith echoed that sentiment, calling it, “the perfect amphibious operation.”

With the capture of Tinian, the Marianas provided the bases the Army Air Forces needed for the bombing of Japan. As a historian wrote, “They were located 1,200 nautical miles from the home islands of Japan—a distance ideal for the B-29 with its range of 2,800 miles. Tinian became the home for two wings of the Twentieth Air Force. Three months after the conquest of Tinian, B-29s were hitting the Japanese mainland. Over the next year, according to numbers supplied by the Air Force … B-29s flew 29,000 missions out of the Marianas, dropped 157,000 tons of explosives which, by Japanese estimates, killed 260,000 people, left 9,200,000 homeless, and demolished or burned 2,210,000 homes.

“Tinian’s place in the history of warfare was insured by the flight of Enola Gay on 6 August 1945. It dropped a nuclear weapon on Hiroshima. Two days later a second nuclear weapon was dropped on Nagasaki. The next day, the Japanese government surrendered.”

In his official history of the 2nd Marine Division, Richard W. Johnston records the reaction when news of the surrender reached the division: “They looked at Tinian’s clean and rocky coast, at the coral boulders where they had gone ashore, and they thought of the forbidding coasts of Japan—the coasts that awaited them in the fall. ‘That Tinian was a pretty good investment, I guess,’ one Marine finally said.”