By Mark Carlson

Even in the age of ultra-sophisticated nuclear submarines, with their advanced computers, sonar, navigation, and communication systems, the hard truth is inescapable: the sea is the most hostile environment on Earth. It is totally unforgiving of human error or overconfidence. The pressures below 2,000 feet can crush a submarine like an aluminum can in seconds. For reasons that even now are a closely guarded secret, that happened in late May 1968 when the nuclear attack submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589) sank in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean as she was returning from a long deployment. Ninety-nine officers and men were on board the Scorpion.

The Scorpion was third in the revolutionary new Skipjack class of nuclear fast-attack subs. She was commissioned at the Electric Boat Shipyard in Groton, Connecticut, on July 29, 1960. The rapidly changing Cold War arena demanded that each one of the U.S. Navy’s nuclear submarines be on continual service for the purpose of locating and tracking Soviet attack and missile submarines. But time and constant service took their toll. The Navy was pushing the Scorpion to its limits; as a result, systems began to break down. There were serious oil leaks in the machinery, and sea water seeped in from the propeller shaft seal. Her depth was restricted to 300 feet, well above the 900-foot test depth. In 1967 she experienced vibration so severe it seemed that the entire boat was literally corkscrewing through the water. The cause was never determined. The crew had taken to calling their boat the “Scrapiron.”

By 1968 it was obvious to the Navy’s Bureau of Ships that the submarine was badly in need of major overhaul. Yet the demands of the Cold War made it necessary to send Scorpion and her officers and crew on one more deployment to the Mediterranean Sea to participate in joint NATO operations.

She would, however, sail with one less man. Electrician’s Mate Dan Rogers, who refused to go on the cruise, flatly stated to Lt. Cmdr. Francis Slattery that every man on Scorpion was in danger.

The crew, while enjoying the occasional liberty in Italy, Sicily, and Spain, grimly worked to keep their weary submarine operating until they reached Norfolk, Virginia, at the end of May. The Scorpion left Rota, Spain, on April 28 and headed west across the Atlantic on or about May 20. Slattery radioed on May 21 that their estimated time of arrival was 1 pm on May 27.

When the Scorpiondid not arrive at her berth at the Norfolk Navy Yard on May 27, repeated calls of Scorpion’s call sign, Brandywine, went unanswered. Even before the fearful family members dejectedly returned home not knowing what had happened to their loved ones, the Navy’s situation room in the Pentagon was full of worried officers who were trying to determine why the submarine had gone missing. On the large Atlantic Ocean wall chart a line was drawn along the Great Circle route from Gibraltar to Norfolk. Somewhere along that 3,300-mile arc the Scorpion and her crew could be struggling to survive a serious mechanical casualty. Or she could be down, a word that had grim implications to the submarine service. In any event she had to be found. One thing was reasonably certain: the Soviets had nothing to do with the disappearance.

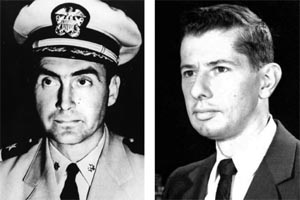

This is where Dr. John Craven, the chief civilian scientist of the special projects division and a skilled engineer, entered the picture. Craven, whose work had made him a legend in the Navy, had been instrumental in finding the lost H-bomb that had fallen into the sea off Spain when a B-52 collided with a KC-97 tanker. He had used a revolutionary method of calculating poker odds and mathematics to determine the probable location of the bomb. Despite universal scorn at his methods, Craven had led the Navy right to the missing weapon. He had been on the team that designed the Polaris missile launching system. Craven was not above unusual ideas. Upon hearing of Scorpion’s failure to arrive at Norfolk, he entered the situation room to see the grim faces staring at the vast Atlantic Ocean chart. He offered to help. Having few options, the Navy accepted his offer. The alternative was a protracted and probably futile air-sea search.

Craven knew that the newly operational sonar surveillance system would be of little help on this search. The system’s array on the sea floor filtered out all noise except that of machinery such as what was used on Soviet subs. He began by examining the readouts of underwater hydrophones located in the Canary Islands and Newfoundland. By linking the time scale of the two readouts, Craven and Naval Research Laboratory acoustic engineer Wilton Hardy found a suspicious series of five to eight underwater explosions around the time Scorpion would have been in the mid-Atlantic. The depth of the water was 11,000 feet, far deeper than any military submarine could survive. “How the hell are we going to find these poor bastards?” Craven wondered.

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Thomas Moorer appointed Craven to head a technical advisory group. The group used estimates of Scorpion’s speed and course, comparing them to the acoustic anomalies found on the hydrophone readouts. Sure enough, all of them fell right on the submarine’s track.

First, there was a single bang, followed 90 seconds later by more underwater rumbles that could only be the fatal sounds of a submarine’s compartments imploding under immense pressure. It took only three minutes and 12 seconds. Then all was quiet. Craven contacted Moorer to inform him that Scorpionwas probably lost. Moorer waited until some word had come in from the search ships and planes. But nothing was found. On June 5, the Navy announced that Scorpion and her crew were presumed lost. At that point, the Navy had to find and examine the wreck. Using the oceanographic research vessel Mizar, a systematic search of the sea floor with towed camera sleds failed to find the wreck west of the point where the first explosion had occurred. This made no sense.

Then Craven’s team noted one odd discrepancy. At the moment of the first explosion, Scorpion had not been headed west, but east. What would make a submarine suddenly change course 180 degrees? Craven asked experienced submarine commanders and in every case he was told the same answer: a so-called hot run torpedo. When a torpedo activates onboard a submarine, it is called a hot running torpedo, which is highly dangerous. A submarine skipper’s immediate response to the warning of a hot run is to order a 180-degree turn. This triggers a fail-safe device in the torpedo that shuts down the warhead.

If Scorpion had experienced a hot run torpedo while on the return voyage to Norfolk, Slattery would automatically have ordered an emergency hard left rudder to turn the boat around as fast as possible. According to the skippers Craven queried, this was drilled into every officer who conned a submarine. The Scorpion had recovered from a hot run torpedo in December 1967, and Slattery had performed exactly that maneuver. This scenario would put the wreckage east, not west of the coordinates of the initial explosion. Few officers gave this theory any credence, but Craven persisted. On October 29, Mizar found the shattered remains of Scorpion right where Craven’s team said it would be. The hull was torn apart by violent forces, the stern was telescoped into the engine room, and the bow was smashed back toward the sail. The entire underside was ripped away. Scattered bits and pieces littered the sea floor like leaves after a storm. There was no doubt—the 99 crew members were dead.

What had happened? Was the submarine sunk by her own torpedo? Like all Cold War subs, Scorpion carried warshots, that is, live torpedoes. She carried 14 Mark 37 electric torpedoes, seven steam-powered Mark 14s, and two nuclear-tipped Mark 45s. It was common practice on an American submarine to perform maintenance on all of the submarine’s equipment and weapons at the end of a patrol. With this in mind, Craven began investigating the possibility that one of Scorpion’s torpedoes had activated during a maintenance check. One of Craven’s favorite maxims was that if a piece of equipment can be installed backward, it will be. Sure enough, he discovered that there had been several instances of torpedoes being activated while undergoing routine electronic maintenance because some of the testing units had transposed wiring. It seemed more and more likely that one of Scorpion’s torpedoes had exploded inside the hull. Craven was personally convinced, but he found no acolytes among the Navy brass.

The Ordnance Systems Command (OSC), the department that oversaw the development and operation of every weapon in the Navy’s inventory, steadfastly insisted that it was impossible for a sub’s torpedoes to explode inside the hull; however, OSC did not deny that hot runs did occur. Understandably, the Navy was not anxious to accept the grim possibility that one of its boats and its crew had been killed by its own torpedo. Even more unnerving was the chance that every one of the submarine force’s torpedoes was flawed. This is the official mindset Craven faced in the fall of 1968.

Examination of the wreck, first by Mizar’s towed cameras, then in 1969 by the bathyscaphe Trieste II showed no sign of serious hull damage in the region of the torpedo room, which would be expected if a warhead had detonated inside. Yet the photos did show that the torpedo room loading and escape hatches had been sprung open. This was a perplexing paradox in Craven’s theory. Try as he might, he could not explain the contradiction.

The Navy Board of Inquiry’s final report suggested several possible reasons for the loss, but nearly all involved equipment failure, not the explosion of a weapon. That was where the matter ended, at least for the next 25 years. The families of the dead crew were left in limbo as to what had really happened.

The Chicago Tribune published a story in 1993 that the Navy had at last released the official report and videos of the wreck on the 25th anniversary of the sinking. Craven, then 69 and retired, was named as being instrumental in the search for the sub. It also mentioned his theory about the hot run torpedo. The article came to the attention of someone Craven had never met.

Charles Thorne had been the technical director of the Weapons Quality Engineering Center at the Naval Torpedo Station at Keyport, Washington, in 1968. Thorne, who was retired, had read the Tribune story and decided that he had to talk to Craven. The two men found that each was sure that Scorpion was lost from an exploding torpedo. But unlike Craven, Thorne had information that shed an entirely new light on the mystery.

The Mark 37 antisubmarine weapon acoustic torpedo, built by Westinghouse, had entered service in 1956. It was a marvel of underwater weapons technology; it weighed 1,400 pounds and was just over 11 feet long. It carried 330 pounds of HDX high-explosive in the warhead. Designed to sink enemy subs by blasting a hole in the tough outer hull, the Mark 37 was a deadly and efficient weapon.

The silver-zinc batteries were about five feet long and separated from the 330-pound warhead by a half-inch-thick partition. But there was a hidden flaw in the design that only became apparent in 1966 when the Mark 37 was already in service. Between the battery and the power cell was a tiny foil diaphragm only 1/7000th of an inch thick. This was supposed to rupture when pressure was applied by the ejection of the weapon from a torpedo tube, causing electrolytes in the power cell to fully activate the battery, which then started the motor. But this tiny part was very fragile and could easily be ruptured by a shock or vibration. The testing lab said the battery had no margin for safety and recommended the design be changed. Under pressure from the submarine fleet, the OSC refused to do so.

In April 1968 even as Scorpion was preparing to leave the Mediterranean and return home, Thorne’s team had been testing the torpedoes and key components. Tests included subjecting them to shock, heat, vibration, and other conditions that might happen aboard a submarine. They subjected one of the 250-pound batteries to strong and sustained vibration. It was mounted on a table, and just as the technicians left the room, a huge explosion made the walls shake. They reentered to find the battery engulfed in blue-green flames that shot nearly to the ceiling. Shrapnel and smoking acid were sprayed all over the room. Only after determined effort did they manage to disconnect the burning unit and extinguish the flames. The battery had been distorted and melted from the intense heat.

A written alert was immediately sent to the fleet under Thorne’s signature. The alert stated that all of the submarines in the fleet that carried Mark 37s with the flawed batteries should disconnect them immediately pending replacement. Even after the test, the OSC continued to insist that it was impossible for a battery explosion to set off a warhead. In fact, an OSC representative berated Thorne for suggesting such a thing in the alert.

The main problem the Navy faced was expediency versus caution. The submarine force needed torpedoes, and the manufacturers were hard pressed to produce the required numbers. As a result, the OSC was rushing into service torpedoes containing components that had not been fully tested. One company, subcontracted to produce the batteries, failed to manufacture even one that passed the quality control tests. But the Navy was in a bind. The service allowed that company to ship more than 200 batteries to the fleet. The unit that exploded in the testing lab was one of these. Upon hearing that Scorpion had sailed with at least one torpedo that contained a defective battery, Thorne became convinced that this was the key to the disaster. Scorpion had been sent to sea with torpedoes that were vulnerable to vibration, and the submarine had a history of serious vibration problems.

When they talked in 1993 Thorne was astounded to find that Craven had not known of the alert. He had assumed that Craven was aware of the flaws in the battery. But as things turned out, Craven was not the only one involved who had not known that the faulty batteries could overheat and explode. The board of inquiry apparently also had not been made aware of this crucial fact. After his talk with Thorne, Craven reasoned that the tiny diaphragm could easily rupture from shock or vibration. If this was the case, the foil might only partially rupture, allowing a miniscule amount of electrolyte to leak into the power cells, which was not enough to start the motor, but could cause overheating and sparking. This is what happened in the lab. But right up to the moment of the explosion there had been no outward indication that anything was amiss. If this had happened in a torpedo on board a sub, the first hint of a problem would be intense heat rapidly building up in the battery compartment until the paint on the body blistered and seared. Only then would a crew member realize the danger and call the control room to report a hot run or hot torpedo. They might have had only seconds to move the weapon into a tube to be ejected into the sea. After his talk with Thorne, Craven was sure that Scorpion did not have those precious few seconds.

Did an overheating battery sink Scorpion and did a warhead cook off? This bears some consideration. The wreck shows that the torpedo loading hatches and escape hatches leading to Scorpion’s torpedo room are open. If a 330-pound HDX warhead had detonated, it would likely have caused sympathetic explosions of nearby torpedoes. If that had been the case, the entire forward section of the submarine would have been torn apart. The wreckage, while severe, does not show any external distortion from massive internal explosions. What is more, unlike virtually every other compartment, the torpedo room was not crushed by external pressure. This is highly significant. It means that the torpedo room was probably already flooded when the submarine sank.

But it would be folly to totally rule out a warhead explosion. In normal operations, when 330 pounds of HDX detonates upon impact with an enemy ship, the force is directed straight ahead to penetrate the hull. But if a battery fire had cooked off a warhead, the resulting blast would be undirected in what is known as a low-order explosion. This might not cause other warheads to blow up, but would very likely blow off the hatches, flooding the torpedo room and dooming the submarine even if all the watertight doors had been sealed. The rest of the crew would have watched in stunned horror as the bulkheads started to wrinkle and bend as the steel was subjected to thousands of pounds of pressure per inch. One by one the compartments, starting with the bow and stern, would be shoved into the main hull, tearing the ship apart. The crew would have been immolated in microseconds as the air was compacted into incandescence. The entire sinking took three minutes and 12 seconds from the first explosion to the final collapse. The result was a long fall and immediate death for 99 American sailors.

To this day the OSC has never acknowledged that Scorpion’s loss was caused by an internal torpedo explosion or even that she had carried one of the flawed batteries. But one year after the loss, OSC did order a redesign of the battery for the next generation of torpedoes. This year marked the 50th anniversary of Scorpion’s loss without a solid answer for the crew’s families.