By Mark Carlson

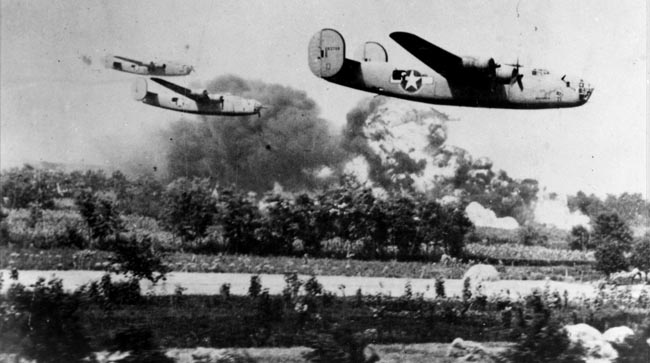

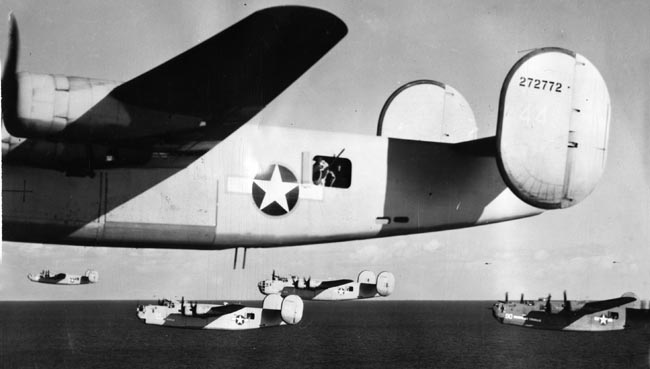

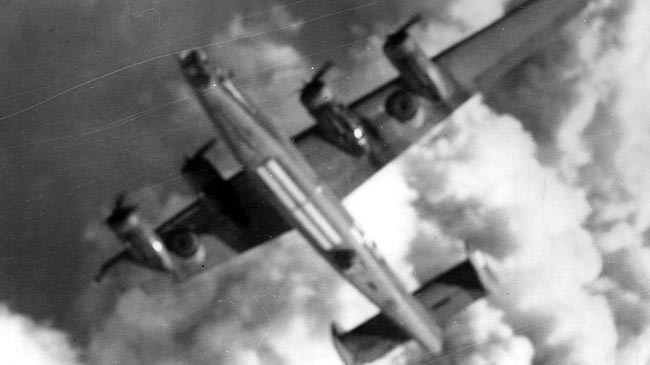

History is almost never “chiseled into stone.” The fog of time can be blown away when new information emerges. So it is with the events of August 1, 1943, in the skies over the Mediterranean and the Balkans. On that fateful day, 178 Consolidated B-24D Liberator bombers of five heavy bombardment groups, carrying more than 500 tons of bombs, left bases in Libya to undertake the longest and most audacious aerial raid in history, a raid codenamed “Tidal Wave.”

The targets were the Nazis’ vital oil refineries around the Romanian city of Ploesti north of Bucharest, near the western shore of the Black Sea.

While it had been carefully planned and tirelessly practiced, Tidal Wave became a fiasco, and a deadly one, too. To this day there have been few military operations that engender more shock and awe than the accounts of the men who participated in that lone low-level mission to Ploesti. And no one who lived through it will ever forget what they saw and heard that terrible day.

Captain Philip Ardery was a pilot in the 389th Bombardment Group, led by Colonel Jack Wood. The “Sky Scorpions” were new to combat, having arrived in England only weeks before being sent to North Africa. Ardery’s B-24 was in the third flight of ships headed for Red Target, the air over which was studded with black puffs of flak:

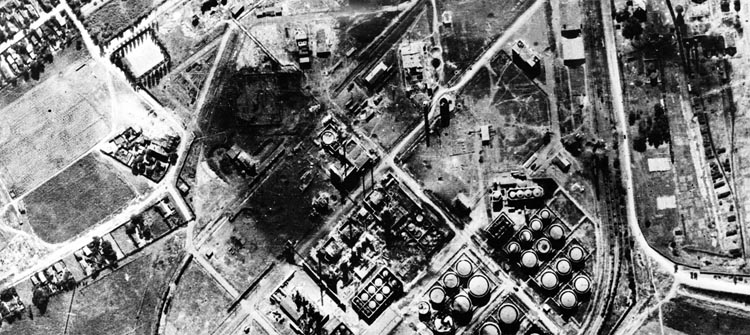

“We were very close behind the second flight of three ships,” Ardery said. “As their bombs were dropping, we began our run in. In the center of the target area was the big boiler house, just as in the briefing pictures. We could see them flying through a mass of ground fire as thick as hail. The first ships dropped their bombs squarely on the boiler house and immediately boilers were blowing up and fires touching off the volatile gases of the cracking plant. The roof of the building blew up above the tall chimneys.

“Already the fires were leaping higher than the level of our approach. Now there was a mass of flame and black smoke reaching much higher, and there were intermittent explosions lighting up the black pall.

“At that moment, running a gauntlet of tracers and cannon fire of all types made me despair of ever covering those last few hundred yards to the point where we could let the bombs go. The antiaircraft defenses were literally throwing up a curtain of steel. From the target grew flames, smoke, and explosions, and we were headed straight into it.”

Ardery recalled, “Suddenly, Sergeant WeIls, our radio operator, called out, ‘Lieutenant Hughes’s ship is leaking gas. He’s been hit hard in his left wing tank.’ I looked out to the right for a moment and saw a sheet of raw gasoline trailing Pete’s left wing. He stuck right in formation with us. He must have known he was hard hit because the gas was coming out in such volume that it blinded the waist gunners in his ship from our view.

“Poor Pete! Fine, religious, conscientious boy with a young wife waiting for him back in Texas. He was holding his ship in formation to drop his bombs on the target, knowing if he didn’t pull up he would have to fly through a solid mass of fire with gasoline gushing from his ship.

“As we were going into the furnace, I said a quick prayer. During those moments I didn’t think that I could possibly come out alive, and I knew Pete couldn’t. Bombs were away.

“Everything was black for a few seconds. We must have cleared the chimneys by inches. We must have, for we kept flying. As we passed over the boiler house, another explosion kicked our tail high and our nose down. We pulled back on the wheel and the Lib leveled out, almost clipping the tops off houses. We were through the impenetrable wall.”

Ardery then saw Hughes pull up and out of formation. “His bombs were laid squarely on the target along with ours. With his mission accomplished, he was making a valiant attempt to kill his excess speed and set the ship down in a little river valley south of the town before the whole thing blew up. Pete was too low for any of them to jump and there was no time for the airplane to climb to a sufficient altitude to permit a chute to open. The lives of the crew were in Pete’s hands, and he gave it everything he had.

“But flames were spreading furiously all over the left side of the ship. I could see it plainly. Now it would touch down—but just before it did, the left wing came off. The flames had been too much and had literally burnt the wing off. The heavy ship cartwheeled and a great shower of flame and smoke appeared. Pete had given his life and the lives of his crew to carry out his assigned task. To the very end he gave the battle every ounce he had.”

Lieutenant Lloyd “Pete” Hughes was one of the five men to receive the Medal of Honor for his courage that day. But he was only one of the 1,752 Americans who took off from Benghazi, Libya, on the most daring air raid in history.

As shocking as Ardery’s account is, it must be remembered that the attack on Red Target was one of the only two successful attacks of Tidal Wave. The rest of the mission had turned into a confused snarl of over a hundred huge bombers desperately seeking a target or escaping from airborne death. What had started out with such promise turned into a catastrophe from poor planning, bad leadership, and overconfidence.

Tidal Wave was conceived by Colonel Jacob Smart, considered one of the best planners in the Army Air Forces. He was well aware of Ploesti’s importance to Hitler’s conquest of Europe and the Soviet Union. Germany had gained control of Romania through diplomatic intimidation and political deception in 1941. While the region had tactical value to the Third Reich, it was the black gold and Ploesti’s refineries that made Romania into what Winston Churchill called the “taproot of German might.”

Together, a dozen modern refineries turned out millions of tons of high-octane aviation fuel and gasoline that kept Hitler’s tanks, trucks, trains, and planes moving in all of Germany’s theaters of operation.

Ploesti’s (pronounced Ploi-yhest) refineries were arranged like the reefs and islands around a lagoon, with the city in the center. They made a difficult target. Only by hitting and destroying specific structures like the boiler houses, cracking towers, powerhouses, and stills would a modern oil plant be put out of action. Pinpoint accuracy on a scale unheard of in high-altitude bomber operations was required.

The only solution that seemed to offer hope was daring and difficult. Colonel Smart began to consider a low-level mission. Medium bombers such as the North American B-25 or Martin B-26 were excellent for the purpose, but the extreme distance from Allied air bases in Africa meant that only long-range bombers such as the Boeing B-17 or Consolidated B-24 could make the round trip.

By the spring of 1943, Smart had found some real advantages to the low-level strike concept. Radar would not be able to detect and track the incoming force. Axis fighters would be cheated of half of their sphere of attack, and ground antiaircraft gunners would have little time to track and aim their guns at the fast-moving bombers. The air gunners on board the bombers would for the first time be able to shoot back. Damaged planes could ditch instead of having their crews bail out.

One by one, the advantages of a low-level raid outweighed the drawbacks. By early summer Smart had sold the Army Air Forces high command on his daring idea. Now they needed five groups of bombers. Two were already available in Africa, based in Benghazi, Libya, which had recently fallen to the Allies.

General Lewis H. Brereton’s Ninth Bomber Command consisted of two heavy bomb groups of B-24s, the 376th “Liberandos” under Colonel Keith K. Compton and the 98th “Pyramiders” commanded by Colonel John “Killer” Kane. The Eighth Bomber Command in England provided three more: Colonel Leon Johnson’s veteran 44th, the “Eight Balls,” and the 93rd “Traveling Circus,” commanded by Colonel Addison Baker. Colonel Jack Wood’s fledgling 389th “Sky Scorpions” filled out the huge force.

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator has entered history as one of the most innovative and important aircraft of World War II. With its boxlike fuselage and distinctive twin rudders, the four-engine Liberator could carry more bombs and fly farther and faster than its more famous predecessor, the B-17 Flying Fortress.

With a crew of four officers and five gunners—the B-24D did not yet have the ball turret—it was a huge plane to be flown at treetop level. All its pilots agreed it was a difficult plane to master, requiring much upper body strength to maneuver its 60,000-pound bulk. But it was the only plane that could manage the 2,400-mile, round-trip flight. Each plane could carry two tons of bombs along with two bomb bay tanks of additional fuel.

The bomb group commanders were awestruck by the audacious concept when they were briefed by Smart and Brereton.

Ploesti was not, strictly speaking, a virgin target. In 1942, 20 B-24s of the Halverson Detachment had been assigned to fly from the East Coast of the United States, down to Brazil, across the Atlantic to Africa, then on to India and China. Their ultimate goal was to bomb Tokyo. But the Doolittle Raid of April had closed all the China bases, and the force, led by Colonel Harry Halverson, was reassigned to bomb Ploesti.

The so-called “Halpro” mission was a hasty, improvised attempt to hit the largest oil refinery in Europe, Astro Romana. It was hoped that cutting off a vital source of fuel to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps might give the Allies the edge they needed to drive the Germans out of Africa. But bad weather and poor navigation caused the 13 ships of the Halpro force to drop their bombs far off target. Until August 1943, Halpro was the longest bombing mission attempted during the war.

For Tidal Wave, seven of the most modern and largest refineries in Europe were targeted.

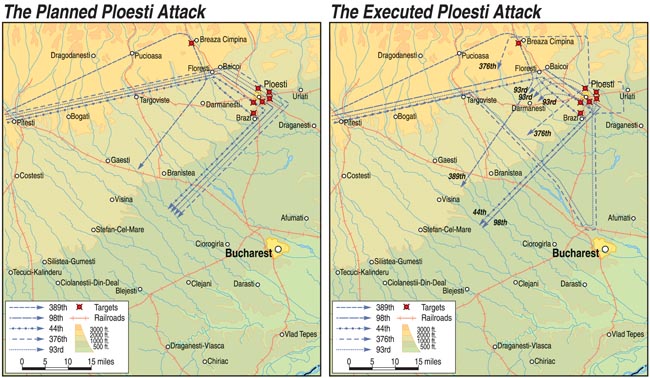

All five groups were to take off in the predawn of August 1 and form up. The 376th was to be followed in turn by the 93rd, 98th, 44th, and 389th. The bomber stream would be almost 20 miles long. They were to maintain visual contact from the start since strict radio silence was to be observed. After flying north over the eastern Mediterranean, the bombers were then to turn northeast at the island of Corfu and head over Albania and into western Romania.

They would then descend to low altitude along the southern foothills of the Transylvanian Alps to reach the third and final Initial Point (IP) at Floresti and turn southeast to the refineries. Timing and distance between groups was critical. They all had to reach the IP at exactly the right time and intervals. Smart intended that the bomber groups make simultaneous turns to their targets, which would be directly in their path.

Compton, in the lead, had White One on the far left, while Baker and the Circus would hit a target designated White Two, west of White One. Baker’s deputy, Major Ramsey Potts, was assigned to White Three, while Kane and the Pyramiders, the largest group, went southeast on the left side of the railroad directly at White Four. To his right, the Eight Balls under Johnson took White Five. Section B of the Eight Balls angled to the right to bomb Blue Target, located southwest of the city.

Meanwhile, Jack Wood’s Sky Scorpions, which included Ardery and Hughes, were to turn northeast at the second IP and attack Red Target at Campina in the valley north of the city. Each bombardier had specific targets for his bombs—the near wall of a powerhouse, for instance. The gunners were to throw out small thermite bombs to ignite fires among the heavily volatile refinery grounds.

It would literally be a tidal wave of huge bombers dropping tons of high explosives in one cataclysmic conflagration. The time from the first bombs on White One and the last on Red Target would take 20 minutes. The first bombs had a delayed-fuse setting of 45 minutes, while the last were set for only 45 seconds. This would ensure that no bombs exploded under the following Liberators.

If all went well, the massive aerial assault would cut a third of Hitler’s oil refining capacity and deal a nearly fatal blow to the Axis in a single mission.

But all did not go well. Tidal Wave only succeeded in destroying two of the refineries and damaging three others at the terrible cost of 53 Liberators. After nearly 16 hours and some of the most savage and desperate fighting ever seen in the air, 440 Americans were dead, more than 300 wounded, and 108 taken prisoner in Romania. Scores were imprisoned in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria or interned in Turkey. Far from being the smashing success planned by Smart, Tidal Wave has become an example of how no plan ever survives first contact with the enemy—or with bad luck.

What went wrong? Some of the causes are obvious when viewed with 20/20 historical hindsight. For one thing, the Germans were fully prepared and alerted long before the B-24s reached the Balkans. The ineffective Halpro raid had one unforeseen consequence: the Germans realized that Ploesti was a key target and began bringing in three fighter groups and hundreds of antiaircraft guns. Radar was constantly on the alert for any incoming raid. The Germans built thick concrete blast walls and complex rapid recovery systems to keep the refineries working even after an air raid. The U.S. Army Air Forces suspected none of this.

Among the official reasons that supposedly contributed to the disaster was the loss of the lead mission navigator on a plane that inexplicably fell into the Ionian Sea. Second, a high storm front over the mountains of Albania further degraded the integrity of the bomber stream. Third, total radio silence made it impossible to regroup without alerting the enemy.

And, finally, a disastrous wrong turn short of the final IP by Compton and Baker caused the leading groups to head for Bucharest instead of Ploesti. After that the entire mission was a shambles and failed to achieve the crippling blow that Smart had predicted. Those are the main points of what history considers the reason for Tidal Wave’s failure.

Yet history can be revised and even changed when new information becomes available. And the best source of information often comes from those who were present.

Major Robert Sternfels is a veteran of Kane’s 98th Bomb Group at Ploesti. On the drive to White Four, Sternfels was in the thick of it, at the controls of his Liberator, Sandman. Sternfels, with more than 300 hours of combat on 50 missions, admitted he had never seen anything like it before or since. He saw it all.

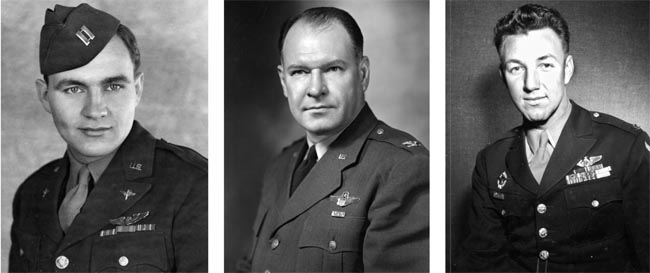

So how did such a carefully planned, rigorously practiced mission that had so much going for it turn into a horrible disaster? According to Sternfels, the root of the debacle lay at the feet of two men: the very man who had originally planned the raid from the beginning, Colonel Jacob Smart, and Colonel Keith K. Compton, commander of the 379th Bomb Group. Together these two men were predominantly responsible for the Tidal Wave calamity.

The South Carolina-born Smart had graduated from West Point in 1931 and became a flight instructor after getting his wings in the Army Air Forces. He tended to catch the eye of senior officers and was soon on the Air Force Advisory Council—under General Henry “Hap” Arnold—where he was involved in the early planning of the invasions of Europe and North Africa. As operations officer for General Lewis H. Brereton’s Ninth Bomber Command, he planned missions to Sicily and Italy. In early 1943, he was tasked to plan the most effective way to destroy the vital Ploesti oil refineries. Smart came up with the idea of hitting the targets with heavy bombers at extreme low altitude.

But as things turned out, he was out of his depth.

“Smart conceived the entire low-level concept,” the 96-year-old Sternfels said in an interview with the author in his Laguna Beach home, “the route, approach, and bomb run for each plane. The four leading groups were to turn southeast onto the bomb run in waves of several planes each, keeping formation in the turn. That was the idea, at least.”

Smart sold the idea, but the men who would actually have to carry it out didn’t think it could be done. Among those was the burly, hard-driving commander of the Pyramiders, Colonel John Riley “Killer” Kane, who never minced words in expressing himself. Sternfels noted, “During the initial mission briefing meeting Kane said, ‘What idiot armchair lawyer from Washington planned this one?’”

Sternfels related an incident that patently demonstrated how ill suited Smart was for planning Tidal Wave. “On 15 July, just two weeks before Tidal Wave, my crew and I were preparing for a mission to Foggia, Italy, when a staff car pulled up. And out stepped Smart, fully geared up in brand-new flight suit and Mae West life preserver. He came up to me and said, ‘I’d like to fly with you today as an observer.’

“Smart was on the flight deck with me, my co-pilot Barney Jackson, and our flight engineer, Sergeant Bill Stout. He was standing there between our seats watching as we went through our checklist. I asked him if he would step back to let my flight engineer come forward and call out speed and engine readings. Smart did so and we took off.”

On the way north toward Italy, Smart again came between the pilots’ seats. Then he did something virtually unheard of in any aircraft.

“He reached out to adjust the fuel mixture controls,” said Sternfels, still astonished after more than 70 years. “You just don’t do that if you’re a passenger. Even a general doesn’t do that without the pilot’s permission. I didn’t say anything but adjusted the mix to what I wanted and we flew on. A little while later Smart did it again!”

That was too much of a breach of protocol for Sternfels. “I said, ‘Colonel, please don’t touch the controls!’ He didn’t say anything. I never forgot about it, and later, after Tidal Wave, I often thought about that mission to Foggia. I wondered if it could relate to how Tidal Wave had turned out.”

“In 1993, I went to South Carolina to interview Smart,” Sternfels said. The meeting between the Tidal Wave planner and pilot was pleasant but held an astonishing revelation. “I always wanted to ask him about his actions in my plane, but I didn’t want to just come out with it. So I asked him in a roundabout way, ‘By the way, how many hours did you have in B-24s before that mission with me?’”

Smart’s answer stunned Sternfels. The man who had conceived and planned the daring and complicated raid said, “I just completed my first check-out ride a week before.”

Until just three weeks prior to the huge mission he had already planned, Colonel Jacob Smart was totally unfamiliar with the B-24 or how it handled in close formation. “I don’t know if he flew a combat mission prior to Foggia,” Sternfels said with evident disbelief.

Sternfels had also wondered about how much the Army Air Forces and Smart knew about the heavy defenses around Ploesti. He asked Smart, “Why didn’t we send some RAF Mosquitos to photograph the target?” Smart said they didn’t want to alert the Germans to the impending raid.

“As if the sudden arrival of almost 200 B-24s in Libya wouldn’t have done that,” Sternfels said laconically. “Ploesti was the only major target that would require long-range Liberators. So our briefings never mentioned the fighters, heavy flak, or barrage balloons around the refineries. We were told the few flak guns were manned by Romanians who would run to the shelters when we flew over. We had no idea how vicious the flak would really be. They knew we were coming. Maintaining radio silence was a moot point. Of course, no one could know that then, so the planners can’t be blamed for trying to keep the Germans in the dark.”

After the war it was established that German radio intercept stations in Athens had picked up the radio traffic during the takeoff. Later, radar units in the Balkans picked up the mission as it headed north from Benghazi and over the Mediterranean. By the time the lead ships passed over the Albanian coast and headed northeast, Ploesti was the obvious target. The German and Romanian gunners and fighter pilots had plenty of time to prepare a warm reception for Brereton’s bombers. They were headed directly at the most heavily defended target in Europe.

But Sternfels reserved most of the blame for the chaos that ensued over the Danubian plains on one man: Colonel Keith K. Compton, who led the mission. “I don’t like to say anything bad of a man who is no longer alive to defend himself,” Sternfels said cautiously. “But Compton was very overconfident and at times even arrogant. He was accustomed to doing things his own way. That was a primary reason for the way the mission came apart.” Sternfels’ reasoning was based on his own observations before, during, and after Tidal Wave, and postwar examination of documents and photos. He interviewed several other Tidal Wave veterans, including Compton himself, then a retired lieutenant general.

Keith Compton was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1915 and graduated from college with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1937. After earning his wings in 1939, he worked his way up the Army Air Forces ranks—first to bomber squadron command and then to the new 376th Bomb Group in North Africa. Compton was known to be ambitious and assertive in both operations and combat.

Compton’s own plane, Teggie Ann, which also carried the mission commander, Brig. Gen. Uzal Ent, took off from Benghazi at 6 am. For the next hour the sky over the airbases was filled with the roar of over 700 Pratt & Whitney radial engines as they blew choking storms of dust and sand for miles.

Berka Two and Terria, the 376th and 93rd bases, were much closer to the coast than Lete, Kane’s field. Once the 40 Liberandos were assembled, Compton put his plane on high-power settings and headed north. In a relatively short time the 376th and the 93rd were far ahead of Kane’s desert-weary ships, which stayed at lower power settings to conserve fuel.

“The gap started at takeoff and widened over the Mediterranean,” Sternfels explained. “Compton never gave a thought to the following groups.” He apparently made no attempt to determine if they were keeping up. But they were falling farther and farther behind.”

Then a curious but tragic thing happened. After a series of violent pitch oscillations, Lieutenant Brian Flavelle’s Wingo-Wangoflipped onto its back and fell into the Ionian Sea, killing all aboard. Another B-24, piloted by Lieutenant Guy Iovine, dropped out of the formation to assist Flavelle. “Iovine later said they wanted to drop life rafts,” Sternfels said, “but that makes no sense at all. There’s no way to drop life rafts from a B-24. They are in compartments on the top of the fuselage. You can’t get at them in flight.” Iovine’s heavily burdened plane was unable to climb to rejoin the mission and had to turn back.

Flavelle’s plane was supposedly carrying the mission lead navigator, Lieutenant Robert Wilson. To make matters worse, Iovine’s plane also carried the deputy mission navigator. So in one bizarre incident, the two most important—and presumably most experienced—navigators were lost to the mission. This was the reason, according to the Army Air Forces, why the leading bombers made the wrong turn at Targoviste instead of Floresti, the third and final IP.

But this, according to Sternfels, was closer to folklore than fact. As for losing the two most experienced navigators, Sternfels stated, “That’s baloney. If only two men knew the route, why did we take along 176 others? All the navigators were well trained and had very cleverly drawn low-level course charts.”

How then, could so many qualified navigators have failed to keep the force on course at the critical moment? They didn’t, according to Sternfels. “The man who made the wrong turn was not a navigator. If Flavelle had really been carrying the mission lead navigator, he would have been flying ahead of Compton, and the rest following. Compton would have seen him go down. But Compton told me when I talked to him in 2000 that he didn’t learn about Flavelle’s crash until he returned to Benghazi nearly 14 hours later. Compton admitted to me that he led the mission from takeoff to landing. I later found documentation in the Air Force archives to back it up.”

This sheds an entirely new light on the events that transpired. By the time the leading groups reached the 9,000-foot Pindus Mountains of Albania, Compton and Kane were separated by at least 30 miles. And the gap was widening with each passing hour.

Ploesti, a controversial book by James Dugan and Carroll Stewart, cites that the storm clouds over the Albanian mountains convinced Kane to begin circling in what was known as “frontal penetration,” a maneuver to prevent collisions in cloud. Frontal penetration had the planes begin flying in a huge racetrack formation until all were involved. Then in small elements of three planes, they peeled off and penetrated the cloud front. When they emerged on the far side they again resumed flying in a racetrack. When all were assembled, they resumed their original course.

This earned a strong comment from Sternfels. “We never did that. That was a fictional explanation for the wide gap between the two formations. But it never happened. In fact, I had never heard of it until long after the war. Our navigation logs show we climbed and worked our way through.”

In any event, there are other reasons to doubt the book’s account. Frontal penetration requires some radio traffic, which was not permitted. Second, the two groups following Kane would have had to do the same, so the maneuver would have taken far longer than can be accounted for by the distance that separated the Compton-Baker group from the Kane-Johnson-Wood group. The book also states that there was a strong tail wind at Compton’s altitude that was not present at Kane’s lower altitude, further widening the gap. This was also untrue, according to Sternfels after his talk with Compton.

At last the leading ships had passed over southern Yugoslavia and entered Romania, descending to the preplanned low level that would screen them from German radar and fighters. Ahead on the left were the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps, a series of ridges and valleys whose rivers and streams emptied into the Danubian plain. The rich land was a peaceful patchwork quilt of farms and pastures, quiet streams and small forests.

The towns of Pitesti, Targoviste, and Floresti were the three all-important Initial Points that guided the navigators to the bomb run. Each navigator had a set of sequentially numbered drawings that showed the details of every landmark along the route. All they had to do was follow the line on the charts as they matched up with the actual landscape.

Sternfels had more surprises in store: “I found a photo of Compton taken just prior to takeoff. In this photo, he is holding under his arm a set of charts and maps. Compton was familiar with the route and approach. But his job as the mission leader wasn’t to be looking at maps. That was Wicklund’s job,” he said, referring to Captain Harold Wicklund, one of the most experienced navigators in the Army Air Forces. Wicklund had flown to Ploesti on the Halpro raid in 1942.

Sternfels interviewed Compton’s co-pilot, Captain Ralph Thompson, who confirmed that Compton had the charts and maps on his lap during the approach to the target area. The lead pilot, the man who did things his own way, was doing the job of his navigator.

“The 376th and 93rd reached the first IP at Pitesti and continued on.” Kane and Johnson were by now almost 60 miles behind the lead force. But Kane, determined to make up the lost time and distance, was driving hard to reach the IP and make their turn.

“When Compton reached Targoviste,” Sternfels said, “which was only the second IP, he unexpectedly turned the force southeast; most of the other pilots realized it wasn’t the right place. Compton ignored their frantic radio calls that they’d turned too early. According to Sternfels, this was typical of Compton. “It would have taken only a few minutes to get back to the correct route.” Such a move would also have given the following groups time to catch up and possibly return the mission to the original plan.

But the Liberando commander, with the mission commander beside him, continued on the wrong course, followed by Lt. Col. Addison Baker and Major Potts with the 39 ships of the Traveling Circus. It is not known whether Baker accidentally made the wrong turn or had decided to follow Compton.

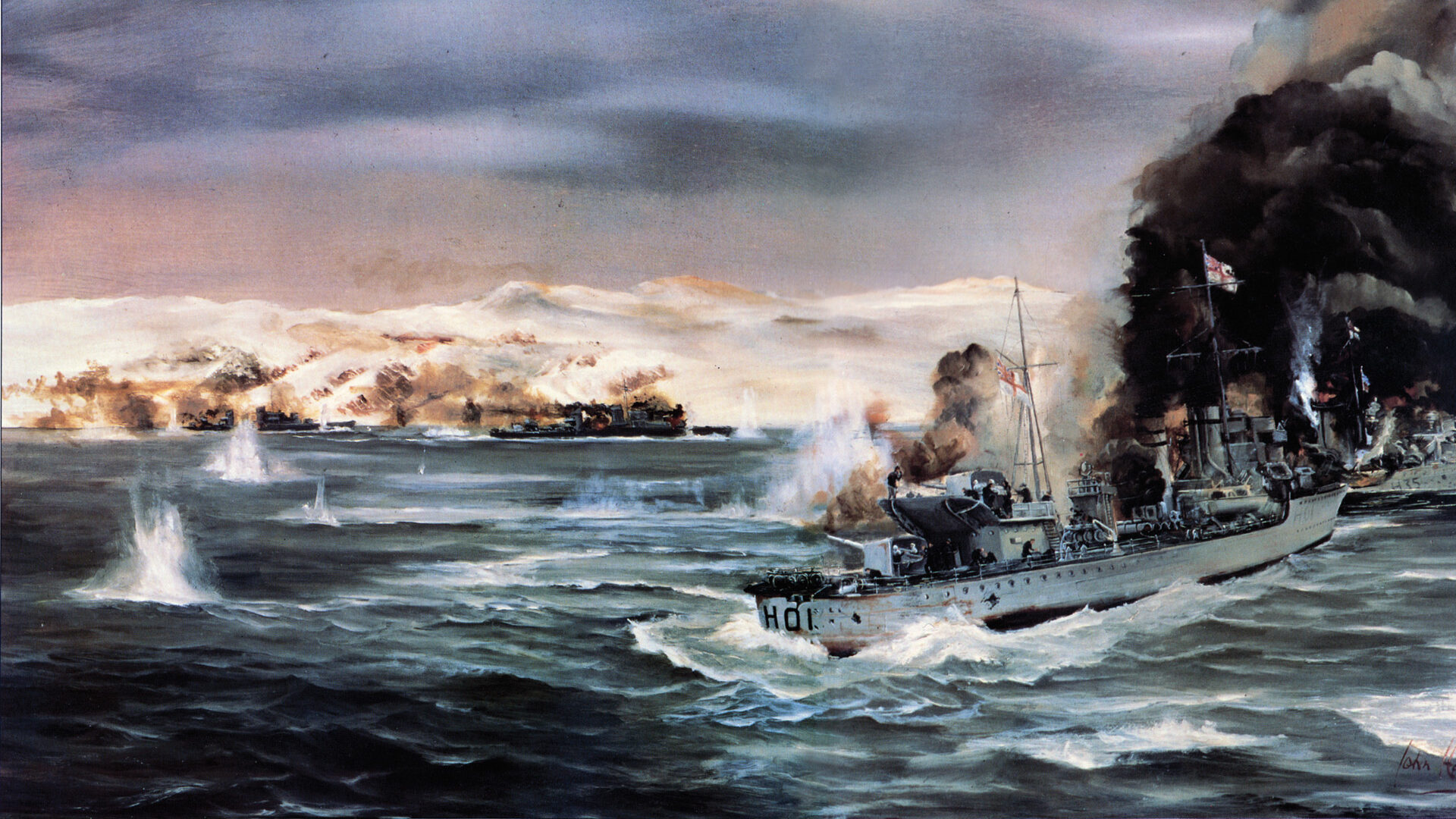

They were now headed directly to Bucharest while they passed Ploesti on the left. Baker and his co-pilot, Major John Jerstad, at the controls of Hell’s Wench,apparently realized their heading was taking them away from their target, now far to the east beyond Ploesti. They turned east to attempt an improvised attack on Kane’s target, White Four, when the Circus flew into a deadly hailstorm of flak. German gunners found easy targets at point-blank range. Huge 88mm and rapid-firing 37mm batteries fired streams of hot steel that wreaked terrible carnage on the low-flying B-24s.

Over the city, refineries, and plains they fell, burning like torches as they shed wings and bodies. Many planes and crews ended up as long, flaming smears of wreckage in the fields around the fiercely burning oil tanks.

When the Circus came out, Hell’s Wenchwasn’t among them. Baker and Jerstad had taken a hit just before reaching White Four, and the fuel-laden Liberator became a flying blowtorch.

Only 12 Circus ships returned to Benghazi.

By this time, General Ent, on board Compton’s plane, decided that the enemy defenses were too fierce to breach. He sent a radio call to the Liberando ships to break off the bomb run and hit targets of opportunity. With this, the B-24s of the 376th began pulling away from the main group.

“It still amazes me,” continued Sternfels, “that General Ent ordered the 376th to break off the bomb run. A lot of pilots just jettisoned their bombs rather than face the flak. They weren’t even under fire when he sent that order.”

Compton’s bombardier, 1st Lt. Lynn Hester, said in an interview with Sternfels, “I was told to drop the bombs but Compton pulled the lanyard on the pilot’s pedestal and dropped them right through the doors, knocking them off their tracks. I never saw the target nor did I see the bombs explode.”

In the Dugan and Stewart book, Compton stated in his debrief that he had dropped his bombs on “what looked like a powerhouse.” But the B-24’s manual reveals that a firing unit switch must be turned on or the bombs will not be armed. This was not done, so Compton’s bombs probably never exploded.

Sternfels commented, “Few of the 376th planes came close to a refinery. Otherwise, they’d have lost a lot more planes flying into that flak.” As it turned out, only five of the 29 Liberandos managed to do any substantial damage with their bombs.

“Those were led by Major Norman Appold, a very smart and excellent pilot,” said Sternfels. When the mission came apart, Appold decided to find a worthwhile target for his bombs. He called his wingmen, “Hang on to your bombs. We’re going to use them.”

He passed the briefed Liberando target, White One, which he did not recognize from this unfamiliar angle. Appold took his improvised element around the city and headed for Concordia Vega, White Two, the target assigned to Baker of the Circus. He and the other four planes approached the refinery at 10 feet of altitude. He managed to avoid the tall smokestacks and Ramsey Pott’s Circus ships coming from directly ahead. His small group destroyed 40 percent of the refinery’s capacity.

Tidal Wave was total chaos even before the three following groups at last arrived at the correct IP and made their turns.

“That turn to the southeast was conceived by Smart,” observed Sternfels, “but it proved that he had no real idea how difficult it is to fly in formation, let alone manhandle huge, overloaded bombers in a critical maneuver. It looked good on paper but that turn was totally impractical.”

This had been proven when they practiced over the desert. A full-scale mock Ploesti consisting of painted lines and poles denoting key aiming points was set up in the desert. The pilots, bombardiers, and navigators trained in the approach to the bomb run and aiming points for their specific targets.

But actually doing the turn while in a tight wingtip-to-wingtip formation proved to be nearly unmanageable. Turning a heavily laden B-24 under ideal conditions was not easy, but doing it when tucked into a 1,000-foot-wide formation was next to impossible. While the planes at the inside of the turn, the hinge, as it were, need only alter their heading, the planes stepped farther out on the line also needed to increase speed to stay in formation. The bombers farthest out would be hard pressed to remain in their assigned slot.

Kane’s ships were arranged in five waves of nine planes each, with 2,000 feet of spacing between waves. His force was on the outside of the turn that included the 44th Bomb Group, headed for White Five and Blue Target. Altogether, more than 90 huge bombers were supposed to make that turn in a swath nearly a mile wide.

“We practiced staying in formation over the desert but didn’t dare try that turn,” said Sternfels. “It was dangerous to try even once, and that was in training, without anyone shooting at us.”

But there was more to contend with that Smart had not considered. When large aircraft fly in close formation, it creates turbulence capable of tossing 30-ton bombers around like leaves in a storm. The Liberator requires a lot of effort to maintain trim, to say nothing of keeping perfect formation.

“The prop wash was fierce,” Sternfels recalled. “Both my co-pilot Barney Jackson and I had our hands full just trying to stay on the bomb run. We were in formation as we reached the correct IP, but after that turn the entire formation was scattered. It was impossible to get it back together in the few minutes we had before we reached the target. My ship was originally in the fourth wave, but we were so tossed around, to this day I can’t tell you which wave we ended up in.”

But Sternfels still has vivid memories of following Kane along the railroad line leading to the city. The Germans had put an ingenious flak train on the tracks paralleling the bomb run, and it hosed deadly point-blank fire into the low-flying B-24s, damaging nearly all the ships closest to the tracks before they reached their targets. The train was shot up by the bomber gunners, but not before German gunners on the ground shot down at least eight planes.

Kane led his 47 planes right into the fires and towering black smoke rising like a solid curtain from oil tanks and pipelines. To his right, Leon Johnson led the Eight Balls toward the untouched White Five. James Posey’s section was angling off to the right to head to Blue Target at Brazi, southwest of the city. The bellicose Kane was angered and perplexed to find his target already burning; Astro Romana had been hit by bombs from Baker’s shattered Traveling Circus. Huge oil tanks were exploding under the low-flying Liberators.

At this moment, three different bomb groups were flying over Ploesti from three different directions. The remnants of the Circus were flying east, while Appold’s small detachment was coming west after hitting their improvised target. Then Kane swept south, headed for the burning White Four. It is incredible that there were no collisions.

General Alfred Gerstenberg, the German commander for the defense of Ploesti, had come out of his headquarters at the height of the raid and watched in stunned wonder as three groups of huge Liberators flew in three directions and altitudes overhead. He was greatly impressed by the daring skill of the American pilots; he had no idea he was witnessing a fiasco.

“When we went into that black smoke,” recalled Sternfels, “I could only use instruments.” Sandmanwas immediately engulfed in total blackness. The air was roiled up from the explosions and fire below.

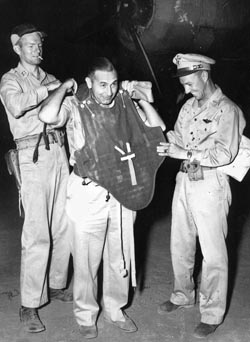

“Balloon cables were all around us,” he said, referring to the low barrage balloons with explosive-laced cables the Germans had tethered over the refineries, “but I couldn’t see them. The right wing struck one and fortunately the propeller broke it. I was more scared at that moment than I’ve ever been in combat. I don’t know what we hit with our bombs. The target was nearly impossible to see.”

A famous photo from the raid shows Sandmanemerging from the pall of black smoke. The B-24 has narrowly missed a tall smokestack. Tidal Wave had become a total debacle. Liberators fell with terrifying frequency as they attempted to get away from the hellish maelstrom of enemy fire and fighters.

At this time, Compton compounded his error. After conferring with General Ent, he sent “MS” for “Mission Successful” to Benghazi. To do this when it was obvious that Tidal Wave had gone disastrously wrong is an indication of how far Compton was willing to go to cover his many errors.

The remaining ships were hard pressed to escape Gerstenberg’s deadly web. From the plains of Romania, over the mountains of Albania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Turkey, the B-24 crews fought for their lives. Some flew all the way back alone, while others sought safety in pairs and groups.

Sixteen hours after it had begun, Tidal Wave was over. The death toll was staggering. Nearly a third of the 1,752 men who took off that morning were dead, while another 300 had been wounded. More than a hundred were in captivity from Romania to Bulgaria. Fifty-three Liberators were lost, nearly a third of the force. Less than 50 were fit to fly. Many men were so exhausted that they needed to be carried off the planes. At last the skies over the eastern Mediterranean were silent.

The pilots of Sandman did manage to bring their ship and crew back to Benghazi, one of the 25 survivors of Kane’s original 47 ships. Of Bakers’ 39 Liberators, only 12 made it home. The Traveling Circus had virtually been wiped out.

After Compton returned to Benghazi, he went into conference with Brereton and Ent. A photo found by Sternfels after the war tells a very compelling story. “It was taken only minutes after Compton’s plane landed,” Sternfels explained. The image shows the side of Compton’s plane, Teggie Ann. Just visible are the torn tracks for the bomb bay doors, a clear indication that the bombs were jettisoned right through them, as bombardier Lynn Hester said.

But there is another, far more compelling story in the photo. “If you look at Compton’s face, he doesn’t look like a man who led a successful mission, nor does he look like someone who ran into a ton of bad luck. He looks guilty.”

While Sternfels admits that this is his own interpretation, it does fit Compton’s supercilious nature. “He always did things his way,” the old pilot said.

From the moment the last propeller came to a stop, the Army Air Forces began the job of evaluating the mission. Reconnaissance photos taken a few days later revealed that only Red and Blue Targets were totally destroyed; White Two, Four, and Five had taken moderate to severe damage. White One and Three were virtually untouched.

The cost in lives and planes had scarcely been worth it. The shocking losses and meager results forced the Army Air Forces to legitimize the mission by awarding five Medals of Honor to pilots, both living and dead. Among them was Colonel John “Killer” Kane, who had the dubious distinction of being both cited for his actions and censured for them. He never again held a combat command. Every airman was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Tactically, Tidal Wave was a failure but strategically it was a moderate success. While it fell far short of the original goal, it did cut off the reserve of vital oil distillation capacity just when Hitler’s war machine needed it most to stop the relentless Red Army’s drive toward the Fatherland.

Suddenly, the Third Reich was short of fuel for combat, transportation, and training. When the Allies took Italy, the new Fifteenth Air Force was established at Foggia. From there hundreds of B-17s and B-24 ranged far into Germany and Austria.

But one goal was now within easier reach: Ploesti. Nearly a year after Tidal Wave, heavy bombers again appeared in the skies over the oil refineries. This time they flew at over 28,000 feet. They took heavy losses but continued to rain high explosives on their targets. While Ploesti never stopped producing fuel, there came a time in early 1945 when the Third Reich was forced to abandon Romania. By then, Germany was living off its rapidly diminishing hump as it used up gasoline and aviation fuel to fend off the advancing Allied armies.

Over the past seven decades Sternfels has tried to find the truth about how the mission went wrong. He scoffed at the official report and even more at what was in the Dugan and Stewart book. At reunions and interviews with fellow Tidal Wave veterans, Sternfels became more convinced that, rather than bad luck, the real reason for what happened on August 1, 1943, rested on the shoulders of Smart and Compton.

“I didn’t set out to prove that Smart and Compton were the cause of the mission failure, but that’s where my investigation eventually led me,” he said. “My talks with both men and my research into official documents and photos further confirmed my conclusions.”

While it could be argued that some of Sternfels’ conclusions are not proven, they are nonetheless compelling and should be taken seriously. They may be the answer that so many historians have sought over the last seven decades to explain why Tidal Wave failed to achieve its grand goal.

Sternfels wrote Burning Hitler’s Black Goldin 2002. The book details the points outlined in this article and contains a great deal of unknown facts about Tidal Wave. Major Robert Sternfels may well have found the long-missing key to the truth about Tidal Wave.