By Alex Zakrzewski

In late 1917, the most successful cavalry charge of World War I took place not on the muddy killing fields of the Western Front, but at the foot of the Judean Hills in southern Palestine. The sun had just begun to set over the desert town of Beersheba on the evening of October 31, 1917, when 800 bayonet-wielding Australian cavalrymen swept out of the arid wilderness like wild horsemen from a bygone age. Though they faced trenches, machine guns, artillery, and aircraft, the Australians succeeded in overrunning the garrison and taking the town, including its strategically important water wells. In the months to come, the audacious charge proved more than just the heroic finish to the epic Battle of Beersheba. It turned out to be a major contributing factor to overall British victory in the Holy Land.

World War I embroiled the Middle East in late 1914, when the Ottoman Empire entered the conflict as a Central Power. For decades the Ottoman Empire had been derided as the “sick man of Europe” because of the constant wars and political troubles that had eroded its once great power and influence. Though the sultan still reigned in Constantinople, real power lay in the hands of a triumvirate of dictators who had seized power during the wars and revolutions of the early 20th century. Militarist, authoritarian, and fervently nationalistic, the new regime was also unabashedly sympathetic to Germany from whom it received military and economic aid. In August 1914, the Ottomans shocked the world by brazenly refusing to close the Turkish Straits to the renegade German warships Goebbenand Breslau,and three months later they officially entered the war by attacking Russian ports in the Black Sea.

The Ottoman entry into the war created enormous problems for the Allies. While its power was not what it once was, the Ottoman Empire still straddled three continents and bordered the Allies where they appeared most vulnerable. Egypt, the Caucasus, and the Persian oil fields all became critical new fronts in a rapidly widening war. The Persian oil fields were particularly crucial because of the Royal Navy’s transition from coal to petrol.

With strong German encouragement, the Ottomans quickly launched two major offensives. The first was a disastrous invasion of the Russian Caucasus, which saw the Ottoman Third Army annihilated by a combination of cold, disease, and Russian forces. The second was much more concerning, particularly to the British, as it threatened the Suez Canal, which arguably was the most important Allied line of communication in the world.

Egypt had been illegally occupied by the British since 1882. Following the Ottoman declaration of war in 1914, the country was made a formal British protectorate complete with a compliant sultan who was installed to give the Egyptians an illusion of self-governance. In truth, the government, economy, and army were all strictly controlled by the British. Their main interest in the country was the Suez Canal, through which flowed the tremendous resources of the British Empire. At the outbreak of hostilities, the British closed the canal to enemy ships and flooded the country with more than 70,000 troops, mainly from India, Australia, and New Zealand. Despite these measures, to many British strategists Egypt’s enormous land area, home to a huge population of resentful, mainly Muslim subjects, appeared ripe for the Ottomans’ picking.

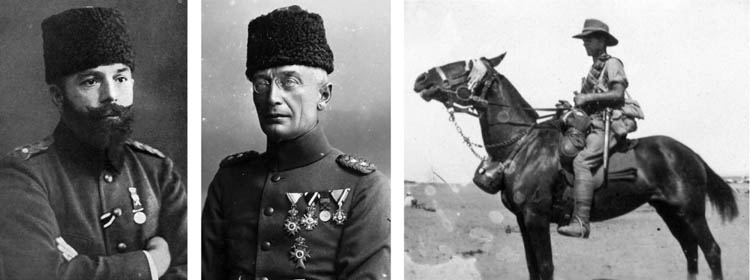

In the first few weeks of January 1915, their worst fears appeared realized when an Ottoman force of 25,000 men crossed the 100 waterless miles of the Sinai and attacked British defenses along the canal. The Ottomans brought with them not only boats and heavy artillery, but also 25 corrugated iron pontoons, prefabricated in Germany and smuggled into the empire through pro-German Bulgaria. Though the overall commander of the operation was officially Ahmed Djemal Pasha, one of the empire’s governing triumvirs, most of the logistical and tactical planning was carried out by his German chief of staff, Colonel Kress von Kressenstein, a talented and experienced officer with years of service in the Middle East.

Luckily for the British, the one thing the invaders forgot was air support, and within a few days of leaving Palestine the long columns of Ottoman troops were spotted by a French aircraft. The large numbers of Arab tribesmen that Ahmed Djemal had counted on to screen the Ottoman advance had also failed to materialize. As a result, by the time the expedition reached the canal the British were well prepared to receive them. After a week of bitter fighting, only one pontoon made it into the water, and just three boatloads of troops managed to row across. The Ottoman artillery knocked out a few of the Allied ships patrolling the canal, but that was the extent of the expedition’s successes. Outgunned and outnumbered, the Ottomans limped back across the desert, having suffered 2,000 casualties.

The Ottomans may have failed in their ultimate objective of seizing the Suez Canal and invading Egypt, but in doing so they opened up a new and costly theater of war. The British in Egypt, though their own casualties were fewer than 200, had also been taught a valuable lesson. The Ottomans were not to be underestimated. Their government may have been corrupt and oppressive and their vast empire torn by interethnic strife, but so-called Johnny Turk, the hardy and resilient Anatolian peasant who made up the bulwark of the Ottoman military, was still capable of incredible feats of courage, endurance, and ingenuity when properly led.

Unfortunately, Allied strategists in Europe did not heed this lesson, and over the course of 1915, they overconfidently blundered into disastrous campaigns against the Ottomans in the Dardanelles and Mesopotamia. Allied defeats on these distant fronts had a profound effect on events in the Sinai as they freed up thousands of battle-hardened Ottoman troops for renewed attacks on Egypt. At the same time in Europe, the fall of Serbia in 1915 and the entry into the war of Bulgaria as a Central Power had also made it easier for Berlin to send weapons and specialists to the Middle East. When the fighting resumed in the Sinai in 1916, the British faced an emboldened and reinforced enemy, more determined and dangerous than before. To meet this new threat, the War Office sent General Archibald Murray, a decorated veteran of the Boer War and former Chief of the Imperial General Staff, to the Middle East to take command of the newly organized Egyptian Expeditionary Force and secure Egypt and the Sinai once and for all.

Loose sand dunes, barren plains, jagged mountains, and sudden sandstorms combine to make the triangle-shaped Sinai Peninsula one of the most inhospitable regions in the world. Murray’s strategy for securing this desolate but strategically important region was to build a standard-gauge railway linking the few crucial desert oases in a defensive network. The railway would also provide his troops with all the supplies necessary for survival in the lifeless desert. Alongside the railway, Murray further ordered the construction of a 12-inch pipeline to provide men and beasts alike with fresh water from the Nile. It was a grueling task that largely fell on the backs of the 13,000 sometimes press-ganged workers of the Egyptian Labour Corps, who had to contend not only with the elements and enemy raids, but also the whips of their overseers.

Following in the path of an ancient caravan route, the railway’s progress was slow but steady, and by mid-April 1916, after two months of toil, it reached the oasis of Katia, roughly 25 miles from the canal. Katia was the westernmost in a series of brackish but vital water sources between Egypt and Ottoman Palestine. It was from Katia that Napoleon had launched his invasion of Palestine in 1799, and it was there that Kressenstein, who had been watching the British advance with growing consternation, sought to stop them from advancing any farther.

In the early morning hours of April 23, 1916, the first of the great Sinai battles erupted when an Ottoman force of 3,600 cavalry and infantry poured out of the desert and around the flanks of the British forces guarding Katia. With the help of an early morning fog, the attackers completely surprised the outnumbered and outgunned 5th Mounted Brigade, whose commander had failed to either reconnoiter Ottoman movements or prepare adequate defensive positions. After several hours of hard fighting, the British fled in panic, having lost almost four cavalry squadrons. It was a humiliating defeat that tremendously raised Ottoman morale and gave them the initiative in the desert war.

A few months later, after building up his forces, Kressenstein struck again, this time north of Katia at the British railhead of Romani. His plan was to pin down the British from the east, then once again swing around their right flank and attack in force from the south. Kressenstein had only 16,000 men, but in another remarkable feat of ingenuity, his troops managed to drag a number of heavy guns across the soft desert sands by creating improvised tracks made of brushwood and wooden boards. Aware that he was outnumbered, Kressenstein was nonetheless confident that his big guns and flanking attack would throw the British off. The British defenders at Romani were awakened at 1 am on August 4, 1916, by cries of “Allah, Allah!” as the Ottomans launched massed infantry assaults against their defenses.

This time, Murray anticipated the Ottoman attack from the south and positioned his troops accordingly. The crux of the British defenses was a large sand dune nicknamed Mount Meredith. The Ottoman infantry, many of them barefoot, attacked the dune with reckless determination. As they struggled to clamber up the sandy slopes, the attackers had to dodge not just the murderous fire of the defenders, but also the rolling corpses of their comrades. The Ottomans slowly drove back the defenders, but with every passing hour more and more British reinforcements poured into Romani along the newly constructed railway. By day’s end, Murray had 50,000 men at his disposal, and it was the Ottomans who were facing encirclement. Short on ammunition and water, Kressenstein had no choice but to call off the attack and retreat to the desert with the ANZAC Mounted Division in hot pursuit.

The authorities in London were now eager to destroy the Ottomans in the Sinai once and for all. Yet Murray refused to be pressured; instead, he continued the slow, methodical construction of his railway and pipeline. It was not until December 1916 that he finally reached the border of Ottoman Palestine. On December 23 his cavalry encircled and captured the town of El Arish, regarded as the gateway to the Sinai, and on January 9, 1917, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force completed its conquest of the peninsula by capturing Rafah on the Egyptian-Palestinian frontier. The loss of Rafah destroyed the Ottomans’ Egyptian aspirations, and they retreated into Palestine never again to threaten the Suez Canal. In less than a year, Murray had conquered an area roughly the size of West Virginia and seemed poised to strike into the Holy Land toward Jerusalem.

As 1917 dawned, British spirits were understandably high as both the troops and the politicians in London believed the Ottomans to be a spent force; however, the fiercest fighting in the desert war was yet to come. Kressenstein and his remaining forces had fallen back to a strong, 25-mile defensive line that ran southeast from Gaza on the Mediterranean coast to the desert town of Beersheba south of the Judean Hills. It was a formidable position protected by a network of entrenchments and fortifications and bolstered by reinforcements from other fronts. It also gave the Ottomans control of the key water sources in the area, meaning they were unhampered by a long, tenuous supply line, unlike the British, who were completely dependent on their ever-lengthening railway and pipeline.

On March 26, 1917, the British attacked Gaza for the first time. Murray hoped to encircle the town and its garrison of 4,000 in the same way that the battles of the Sinai had been won. Before dawn the cavalry was sent racing around the city from the northeast and actually succeeded in encircling the defenders. Unfortunately, the main infantry assaults had been delayed by dense fog, and despite a deafening artillery bombardment they were quickly bogged down by difficult terrain, lack of visibility, and enemy fire. Still, the attackers pressed on; even with mounting casualties, by day’s end the city was almost completely captured. Kressenstein, believing Gaza about to fall, ordered a relief column to halt. Then, inexplicably, just as the battle appeared won Murray convinced himself that the cavalry was too low on water and ammunition to continue fighting and ordered a withdrawal.

Murray’s troops were enraged at having to give up their hard-won gains. Their rage was compounded a month later when they once again assaulted Gaza only to learn why the city’s name literally meant fortress in ancient times. The Ottomans correctly presumed that after their embarrassing withdrawal the British would return in force, and they spent the weeks in between attacks fortifying the city with trenches, barbed wire, machine gun nests, and artillery emplacements. To his credit, Murray knew a hard fight lay ahead. He used every weapon in his arsenal, including 4,000 gas-tipped artillery shells and eight tanks, the latter yet to be used in the Middle Eastern Theater. Royal Navy battleships stationed offshore pulverized the Ottoman defenses ahead of the infantry assaults.

The Second Battle of Gaza, which began April 17, 1917, resembled a typical Western Front offensive—that is, an extensive artillery bombardment followed by mass infantry assaults resulting in heavy casualties for the attackers. For three days, Murray’s men attacked the Ottoman positions, and each time they were bloodily beaten back. The artillery and naval bombardment made little impact on the dug-in defenders, who responded with a devastating enfilade of machine gun and artillery fire.

Just like their comrades in France and Flanders, the British in Palestine learned the hard way that a well-armed, well-entrenched, and determined enemy was almost impossible to overcome through frontal assault. It did not help that the poison gas and tanks, the two surprise weapons on which Murray had pinned so much hope, proved useless in the desert. While the former evaporated in the scorching heat, the latter’s machinery clogged and broke down in the fine desert sand. By the time the Second Battle of Gaza was called off, the British had suffered 6,500 casualties, more than three times that inflicted on the Ottomans.

Murray desperately tried to save face, and save his job as well, by portraying the two attempts on Gaza as British victories that had cost the defenders crucial troops and resources. The press bought it, but the authorities in London were not fooled. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who had succeeded Herbert Henry Asquith in December 1916, and his War Cabinet had lost faith in Murray. The fall of Baghdad in March 1917, coupled with the Arab revolts in Jordan and Syria, convinced them that the Ottomans were on their last legs, and all that was needed to knock them out of the war entirely was one more big push. To make that push they would need an imaginative commander willing to take risks, something they could not expect from the cautious, methodical Murray. Their choice to replace him would prove one of the smartest appointments of the war.

Lieutenant General Sir Edmund Allenby was a hero of the Boer War and one of the most experienced cavalry commanders in the British Army. In 1914, he had led the Cavalry Division during the retreat from Mons before eventually assuming command of the Third Army. Regarded as a “cavalryman’s cavalryman,” Allenby was a bold and aggressive commander whose tactical instincts called for rapid movement and daring maneuver, qualities ill suited to the static trench battles of the Western Front. In the vast expanses of southern Palestine, however, he was in his element, and he brought with him a sense of purpose and determination that the demoralized Egyptian Expeditionary Force sorely needed. Unlike Murray, who preferred to command from a desk in the Savoy Hotel in Cairo, Allenby placed his headquarters on the front lines where his barrel-chested frame and explosive temper quickly earned him the nickname “the Bull.” Although his men may have lived in fear of his surprise visits and inspections, they also quickly came to appreciate their new commander’s confidence and hands-on style of leadership.

Allenby immediately recognized the futility in attacking Gaza for a third time and began to explore possibilities for an attack elsewhere along the Ottoman lines. By the summer of 1917, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force had grown to a formidable force of almost 100,000 men, including 15,000 cavalry. Organized into the XX, XI, and Desert Mounted Corps, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force greatly outnumbered the 33,000 Ottoman infantry and 1,400 cavalry they now faced. In guns and planes, Allenby held a considerable advantage as well. He could also boast a powerful ally in the rebellious Arab tribesmen of the Hejaz. Led by the mild-mannered British intelligence officer Colonel T.E. Lawrence, the Arabs had seized the Red Sea port of Aqaba and were poised to cut the Ottomans off from the Arabian Peninsula entirely. Clearly, it was not a question of force, but of where best to exert that force.

Allenby ultimately settled on a plan devised by one of his most competent officers, Lt. Gen. Philip Chetwode, which called for an attack on Beersheba at the other end of the Ottoman line. Beersheba itself was an ancient but otherwise unremarkable desert town at the foot of the Judean Hills. It had been founded by Abraham and his son Isaac, according to the Bible, and over the course of its long history it had changed hands innumerable times. In recent years, the Ottomans had built Beersheba into something resembling a prosperous town complete with an electric station, hotel, and school; however, it was not the town itself that so enticed the British, but rather the crucial water wells on which it sat. Taking Beersheba would not only pierce the hitherto unbreakable Ottoman line, but it would also give Allenby a reliable water source with which he could conceivably roll up the entire Ottoman line, outflank Gaza, and then strike north toward Jerusalem.

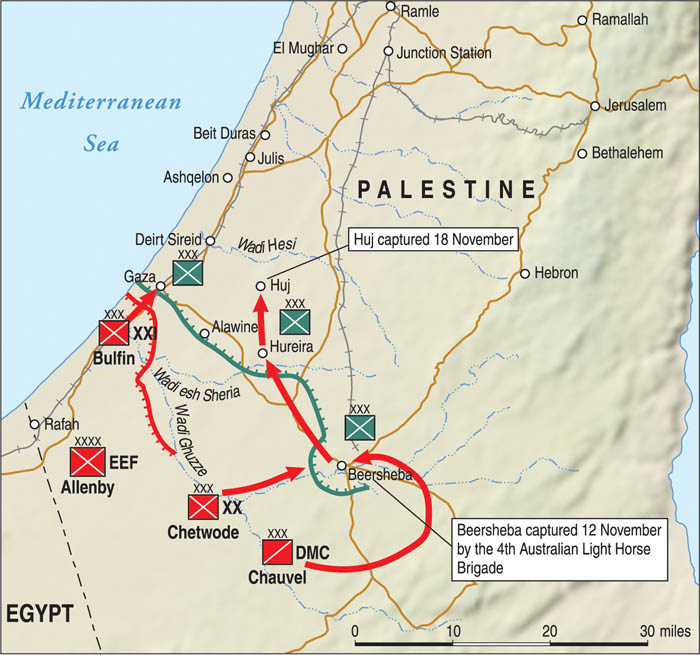

Chetwode’s plan was expanded into a major offensive against the entire length of the Ottoman line. To draw the Ottoman troops away from Beersheba, XXI Corps would launch diversionary attacks against Gaza. These attacks would be preceded by an almost week-long artillery bombardment from both land and sea to really convince the Ottoman commanders that Gaza was once again the Egyptian Expeditionary Force ’s main objective. With the Ottomans distracted in the north, XX Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps would attack Beersheba, the former from the south and west, and the latter from the northeast, where they would also cut the town off from reinforcements from the north.

The plan was sound enough in theory, but there were numerous practical realities to consider. The first was water. The area surrounding Beersheba was barren wilderness, which meant that not only would the British troops attacking Beersheba have to bring what water they needed with them, but the town would absolutely have to be taken on the first day. If the battle for Beersheba dragged on or, worse yet, if the Ottomans destroyed the town’s wells, the attack would have to be called off and the entire plan would be ruined.

There was also the question of how to move large numbers of men and animals across miles of featureless desert without the Ottomans taking notice. Kressenstein knew that a British offensive was in the works, and though Gaza seemed like the logical target he watched the British lines closely for any suspicious activity. Allenby took every precaution to keep him guessing. As his men moved closer to their deployment areas, camps and supply depots were left standing with fires and lanterns burning. A dummy railway complete with its own station was built in the north approaching Gaza, while in the south the real railway and pipeline were covered with brush during the day to hide them from enemy aircraft. The British even constructed depots and camps on Cyprus to give the impression of a pending amphibious landing behind Ottoman lines. However, it ultimately was a brilliantly simple piece of counterintelligence that, more than anything else, convinced Kressenstein that the British were still planning to strike again at Gaza.

At some point in mid-September 1917, a British intelligence officer rode out with a small party into the desert toward the Ottoman lines and deliberately attracted the attention of an enemy patrol. Sources are conflicted over whether it was Major Richard Meinertzhagen or Captain A.C.B. Neale. After a brief scuffle during which shots were exchanged, the British raced back to their own lines, leaving behind a haversack spattered with horse blood. Inside was a large sum of cash, some forged personal letters, a large map with unit locations marked, and confidential papers that outlined plans for an attack on Gaza and a diversionary attack on Beersheba. When the Ottoman patrol returned with the haversack, it was immediately sent to Kressenstein and his staff, who thanked their lucky stars for such a fortuitous twist of fate. In their minds, there was now no question where the British would attack.

Lloyd George urged Allenby to deliver Jerusalem as a Christmas present to a war-weary British nation, yet the British commander refused to move until all the pieces of his plan were in place, and it was not until October 26, 1917, that the attack on Beersheba finally began. While British guns and ships pounded Gaza in the north, in the south thousands of men, horses, and camels began creeping stealthily across the desert toward the Ottoman lines. They brought with them more than 100 artillery pieces, including 60-pounders and 6-inch howitzers. In an indication of the changing nature of warfare, alongside the plodding, camel-driven supply caravans rolled a fleet of 150 trucks and tractors that, despite their troublingly loud engines, proved invaluable for towing the cumbersome stores of artillery ammunition.

The no man’s land between the British and Ottoman lines was a wilderness of arid plains and rocky hills interspersed by numerous dry wadis. In an effort to maintain secrecy, the attackers advanced mainly at night following in the path of lanterns stealthily planted by reconnaissance patrols during the day. During the daytime hours, the men and their baggage trains hid in wadis and gullies, making sure to cover their zinc and copper water tanks with blankets to hide their glinting from the enemy planes that occasionally appeared overhead. The slow progress and bitterly cold desert nights, coupled with the constant fear of detection by the enemy, frayed the men’s nerves and created a tense atmosphere allayed only by the daily rum rations.

It was a testament to the careful planning and execution of Allenby’s plan, as well as his deceptive measures, that this enormous mass of men, animals, and machines was able to advance on Beersheba without raising alarm. Cover was almost blown a few days before the main attack when two battalions of cavalry crashed into a sizable Ottoman patrol. A fierce fight ensued in which the Ottomans brought in artillery and both sides called for reinforcements. Much to the relief of the British, the Ottomans simply dismissed the encounter as a British reconnaissance in force and retreated to their own lines, such was their conviction that the main attack was going to be at Gaza.

On the night of October 30, 1917, the attacking divisions of XX Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps moved into their attack positions. Beersheba’s defenses had been well scouted and plotted by British intelligence staff, and they had a good idea of what to expect. The town itself was fortified by a trench system that was strongest to the west and south but largely unfinished from the east and north. Three miles farther out from the town there was another line of defenses, but it too was discontinuous, particularly from the north and east. The major obstacles to the east were a series of small hills that could prove to be stubborn obstacles if properly defended. Once across these hills, however, the ground approaching Beersheba from the east was a gently sloping, featureless plain.

The town’s garrison numbered no more than 5,000 men, including cooks, clerks, and orderlies, and boasted 20 field guns and 56 machine guns. It was a paltry force, and to fill the broken lines of trenches the garrison commander, Ismet Bey, had been forced to dismount his cavalry and deploy them as infantry. To make matters worse, a good portion of his men were Arab conscripts whose loyalty to the sultan and the Ottoman war effort was suspect. During a visit from Kressenstein on October 15, just over two weeks before the British attack, Ismet had asked for more reinforcements with which to extend the two trench lines. Kressenstein assured him that such measures were unnecessary as the British were definitely planning to attack Gaza. Moreover, if there was to be an attack on Beersheba it would have to come from the west where the trenches were strongest because water sources were more plentiful in that direction.

The British plan of attack on Beersheba looked simple enough on paper but would be extremely difficult to execute given the distances and time constraints involved. Although the 60th and 74th Infantry Divisions attacked the outer ring of Ottoman trenches from the southwest, the cavalry divisions of the Desert Mounted Corps would swing around Beersheba from the east, cut the road north, and attack the town where its defenses were seemingly at their weakest. To maintain surprise, the night before the attack the infantry and its supporting artillery would have to march up to eight miles through freezing darkness to a point within 2,000 yards of the Ottoman trenches. The troopers and horses of the Desert Mounted Corps would have the hardest time. After leaving their camp about 16 miles southeast of Beersheba on the afternoon of October 30, they would have to ride all night then fight all day to achieve their objectives. Not only would men and horses be without sleep for more than a day, but the horses would have to go at least 24 hours without being watered, which was the maximum limit allowed by official regulations.

At dawn on the morning of October 31, 1917, the Battle of Beersheba began with a furious artillery bombardment of the Ottoman positions to the southwest. More than 100 guns erupted along a three-mile front. Their main target was Hill 1070, which offered a commanding view of the Ottoman trenches. After the wire-cutting parties reported the positions sufficiently pounded, the attackers quickly overwhelmed the few defenders still alive, and the rest of the 60th and 74th Divisions surged past the hill toward the main Ottoman trench line. By that point the sun had risen, exposing the attackers to a withering machine gun and artillery fire that briefly brought their advance to a halt. The pause was only temporary, however, and by noon the British guns had once again done their job, allowing the attackers to storm the trenches and in some cases advance as far as 11/2miles beyond.

In the east, the cavalry of the Desert Mounted Corps made good progress as well, and by noon the road north had been cut. The most formidable obstacle was Tel el Saba, a 1,000-foot outlier of the Judean Hills to the north that the Ottomans had fortified with strong positions for their machine guns and artillery, all of which enjoyed excellent fields of fire.

It fell to the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the 3rd Australian Light Horse to take this difficult position on which the easterly approach to Beersheba depended. By attacking in sections, some firing and others advancing, the ANZAC troops slowly scaled the rocky slopes despite a lethal hail of enemy fire whizzing above their heads. When they were within 200 yards of the Ottoman entrenchments, the New Zealanders fixed bayonets and pushed the attack home. The sight of the cold steel coming at them proved too much for the exhausted defenders, who broke and fled back to Beersheba.

It was by then 3 pm, and the outer ring of Ottoman defenses had been completely overrun by XX Corps and the Desert Mounted Corps, but the fight on Tel el Saba had taken longer than expected and the British were quickly running out of time. With dusk just two hours away and the Ottoman defenders rapidly regrouping in Beersheba itself, the next move had to be decisive. With each passing minute, the threat of the wells being blown also dangerously increased. The commander of the Desert Mounted Corps, Lt. Gen. Harry Chauvel, surveyed the open plain east of the town, and his cavalryman’s instinct immediately recognized the incredible opportunity that had presented itself. Wasting no time, he ordered the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Regiments to mount a cavalry charge to overrun the Ottoman defenses from the east and take the town.

It was an incredulous order in many respects, and it brought on a heated debate between Chauvel and his officers. The commander of the 5th Mounted Yeomanry argued that neither regiment was equipped to mount a charge as both were really mounted rifles without sabers or lances. Others argued that advancing across the open plain would expose the troopers to a galling fire from the Ottoman trenches. Both were sound arguments, but the two regiments were also in a uniquely advantageous position to carry out such a daring feat. For one, both were relatively rested, having spent the day waiting in reserve in a wadi. Moreover, though they surely would be briefly subject to a fierce fire, the Ottoman trenches on Beersheba’s eastern side were discontinuous and without wire, making them particularly vulnerable to such a sudden and overwhelming attack. These considerations settled the matter, and at about 4 pm the troopers of the two Australian Light Horse regiments received the order that would earn them a legendary place in the annals of military history: “Tighten up all your gear. In ten minutes we are going into Beersheba.”

To reach their objective, the Australians would have to cross four miles of bare, gently sloping ground. They could not see the Ottoman positions as they were completely obscured by a thick cloud of dust that the artillery had thrown up earlier that day. The troopers’ only point of reference was the town’s white-domed mosque, which stood out clearly against the dark terrain. As they crested a low hill onto the plain, they formed a long line with the 4th Regiment on the right and the 12th on the left. The squadrons formed three lines, each about 600 yards apart with approximately 15 feet between each trooper. Altogether, the two regiments numbered about 800 men, though they were further supported by two batteries of horse artillery and the 11th Australian Light Horse Regiment, which was held in reserve. Behind them trailed the horse ambulances and stretcher bearers.

The advance started with a trot, then a canter, and after covering about a mile of ground, the troopers spurred their horses into a gallop. As they did so, two German planes suddenly appeared overhead and strafed the regiments, but to surprisingly little effect. The Australians may have looked painfully vulnerable on the open plain, but their speed coupled with the great clouds of dust thrown up by their horses’ hooves made them hard targets. This did not stop the Ottomans from unleashing a devastating storm of rifle, machine-gun, and artillery fire, and soon after breaking into a gallop, men and horses began crashing to the ground with crippling force. With no cover available to them, the troopers could only crouch low behind the necks of their frothing, maddened mounts, many of whom were galloping purely out of terror and instinct.

After the charge it was revealed that the Ottomans had expected the Australians to stop and advance dismounted, and many did not bother adjusting the range on their rifles or guns. Nonetheless, the enemy’s fire only intensified the closer the horsemen got to the trenches. As shells continued to burst overhead, grenades and point-blank rifle and machine-gun fire cut holes in the attacking squadrons. It was a hellish scene, almost impossible to describe, and made all the more frightening by the thunderous pounding of hooves and great clouds of blinding dust. When the Australians were within a few hundred yards of the Ottoman trenches, they added a new element of terror by drawing their bayonets and waving them in the air as if they were sabers. The glinting of the blades in the setting sun filled many of the defenders with fear, and they began to abandon their positions and fall back on the town.

The 12th was lucky enough to approach a section of trench that was largely unfinished, and they easily sped past the defenders and onto Beersheba’s dusty streets. The 4th faced a better prepared trench system, in places three lines deep, and they were forced to dismount and fight hand to hand. Many troopers leaped off their horses directly into the trenches with bayonets and pistols in hand, some using their rifles as clubs. Others stayed mounted and simply hopped over the 10-foot-wide trenches and continued into the town. A number of troopers later reported having their horses die suddenly beneath them for no apparent reason. A gory trail revealed that their stomachs had been torn open by Ottoman bayonets as they leaped the trenches; the poor beasts had continued galloping as long as they could before collapsing.

The fighting was savage and witness to many incredible individual acts of courage. One trooper, Staff Sergeant Jack Cox, captured 40 prisoners including a machine gun crew with nothing more than a revolver and an evil look on his face. Some defenders were happy to surrender and even offered their attackers money to spare their lives. Others fought to the bitter end, including many of the derided Arab conscripts. Amid the chaos, some defenders surrendered only to return to the fight once their captors had moved on. They were shown no mercy by the supporting waves of horsemen. Despite the fierce resistance, within 10 minutes of reaching the trenches the Australians had completely overrun the town, and soon the rest of the besieging British forces were descending on Beersheba from all directions.

The attackers briefly received a terrible scare when two explosions suddenly shook the streets. A retreating German officer had taken the initiative to blow two of the wells before retreating with the remainder of the garrison. Fortunately, he was captured before he could detonate any more, and as the sun set over the town the exhausted British forces watched triumphantly as a terrified mob of Ottoman troops, including Ismet Bey and his staff, fled north into the hills, some vainly trying to drag their guns behind them. By nightfall, Beersheba and its precious water wells were firmly in British hands.

Incredibly, only 31 troopers and 70 horses died during the charge, a testament to the surprise and speed of the maneuver. The majority of the 1,250 British casualties during the battle had been suffered by the infantry in the south and around Tel el Saba in the east. Ottoman casualties are not certain, but the trenches were full of their dead, and more than 1,000 Turks were taken prisoner.

As the British consolidated their victory, they were disappointed to discover that Beersheba’s water supply was much smaller than they expected. However, the capture of the town destabilized the entire Ottoman defensive line. Over the course of the following week, further breakthroughs occurred, and one week after the taking of Beersheba Allenby marched into Gaza. Though the Ottomans continued to fight stubbornly, there was now no stopping the relentless British advance into the Holy Land. On December 9, 1917, Jerusalem surrendered to Allenby well in time for Christmas.