By David H. Lippman

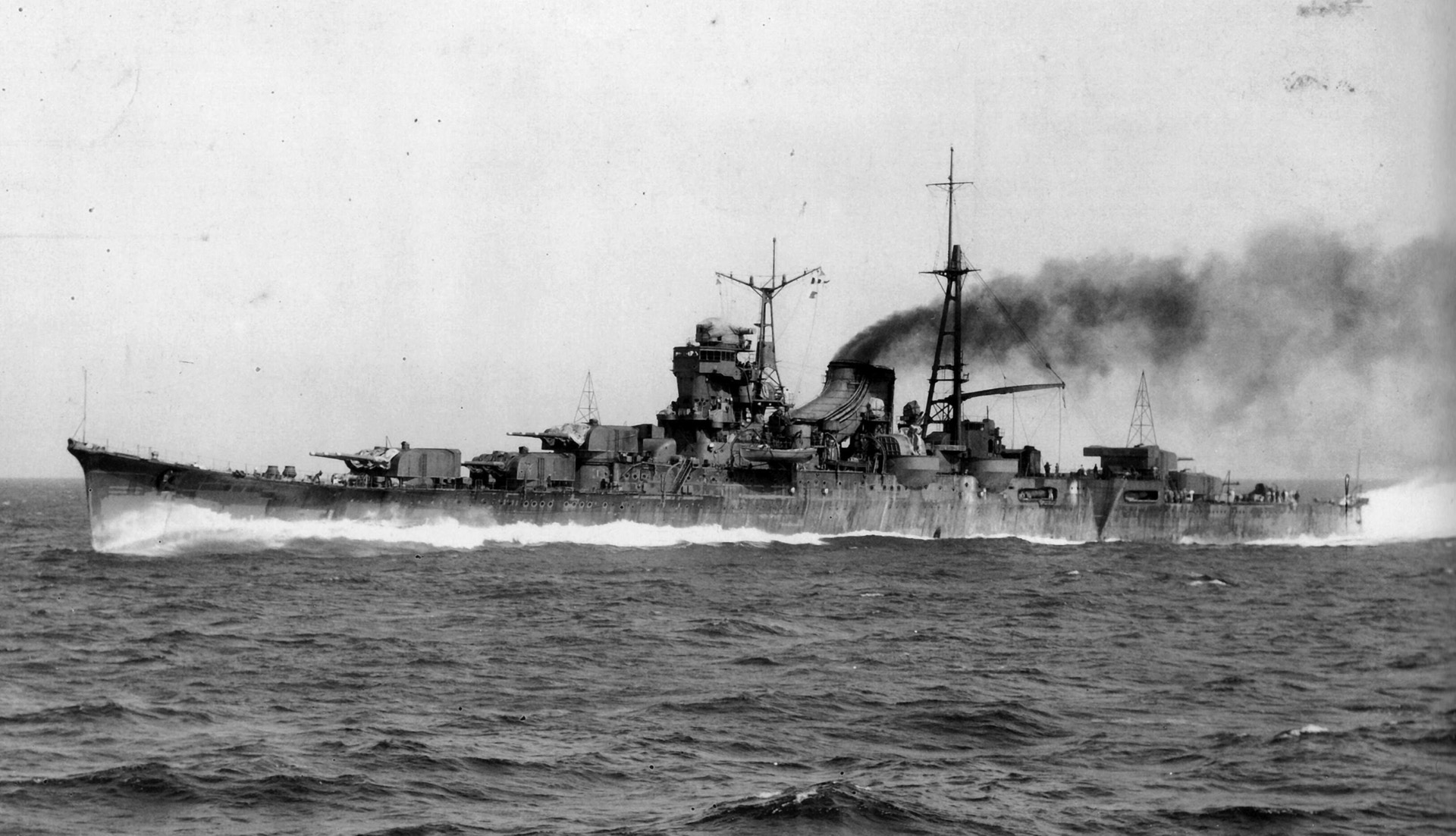

She was the lead ship of her class, built under the 1930 London Naval Treaty, which imposed limits on cruiser, destroyer, and submarine tonnage for the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. Four ships were built in the class, with Mogami slipping down the ways on March 14, 1934, at Kure Navy Yard. Mogami would go on to a lengthy but luckless career in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The Mogami, like her sisters, displaced 13,440 tons, could crack the waves at 35 knots, and packed 10 8-inch guns and 12 Long Lance torpedoes. With her bulky superstructure, she vaguely resembled a battleship and was a formidable weapon of war.

She was also a popular assignment for her 850-man crew. Mogami and her sisters were air conditioned and had steel tube bunks in place of hammocks for the seamen, cold water drinking fountains dispersed throughout the ship, and more extensive refrigeration spaces for food, which meant better chow. Like all Japanese ships, Mogami had several pickle lockers in different parts of the ship, for careful study had found that a crew that ate pickles daily was more efficient than one that did not. The air conditioners proved noisy and were not installed on future ship classes.

All four ships of the class—Mogami, Mikuma, Kumano, and Suzuya—were assigned together as Cruiser Division 7 (CruDiv 7). Bad luck began right away. In late 1935, Mogami suffered typhoon damage, her bow crumpled in her first deployment due to poor welding. The crew found the hull had warped so badly they could not train her turrets. An investigative board ordered the ship disarmed and drydocked for massive reconstruction.

By now Mogami had a reputation as an unlucky ship, but when war broke out she flew the flag of Rear Admiral Shigenoshi Inoue in the assault on Malaya and Borneo. Her 8-inch guns covered landings in these invasions.

Her next stop was the Sunda Strait battle, where she and Mikuma were covering the Japanese landing at Bantam Bay in Java. Some 50 Japanese transports of various sizes were unloading troops. The American heavy cruiser USS Houston and the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth, fleeing Java by way of the strait, came upon these targets and charged, hurling shells. The Japanese transports and their close escort, the destroyer Fubuki, called for help, and Mogami and Mikuma raced to the scene, joined by the light cruiser Natori and 10 destroyers.

Mogami fired a spread of six torpedoes at the Allied ships; the salvo scored several hits, sinking five targets. Unfortunately, they were the Japanese Army landing ship Ryujo Maru, the Army transports Sakura Maru, Tatsuno Maru, and Horai Maru, and the Navy minesweeper W-2. Also dumped unceremoniously in the drink was Lt. Gen. Hitsohi Imamura, commanding the 16th Army. He clung to a piece of driftwood for 20 minutes and was picked up by a passing boat. That vessel, overloaded with heavy equipment, listed more and cascaded its gear and the general into the sea “with a dreadful sound.” Once ashore, the soggy general sat down on a bamboo pile, and his aide “limped over to him and congratulated him on his successful landing.”

Commander Shukichi Toshikawa, who commanded the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, was later chosen to apologize to Imamura on behalf of the Imperial Navy for the incident and approached Imamura’s chief of staff to do so.

“Don’t tell General Imamura,” responded the chief of staff, in alarm. “He thinks the American cruiser Houston did it. Let her have the credit.” Houston carried no torpedoes, however.

However, Houston and Perth were soon surrounded by Mogami and other Japanese warships and subjected to a massive barrage of shells and torpedoes. Perth went down five minutes after midnight, on March 1, and Houston hung on a little longer, until 12:33 am, when Seaman William F. Stafford, standing on the sloping fantail, sounded “Abandon Ship” with his bugle. The “Ghost of the Sunda Strait” sank 12 minutes later, her battle flags still flying.

Interestingly, one of Houston’s prewar captains was Jesse Oldendorf, who avenged the destruction of his old command at Surigao Strait in 1944 by sinking her tormentor, the Mogami.

After that, Mogami joined Rear Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s cruiser force, assigned to support Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s April 1942 raid into the Indian Ocean. Nagumo took five carriers into battle, sinking a British carrier and two cruisers. Mogami joined in the April 6 sinking of two Norwegian cargo ships, the 4,434-ton Dagfred and the 1,515-ton Hermod. All of the crewmembers of both ships survived their sinkings.

Mogami’s next assignment was with CruDiv 7, under Rear Admiral Takeo Kurita, at the Battle of Midway. CruDiv 7’s job was to carry out a nighttime bombardment of the American-held atoll prior to the scheduled Japanese invasion. After the Japanese carrier force was slaughtered on June 4, the bombardment mission was ordered for the next evening anyway. Sanity prevailed, and Kurita’s ships were recalled when they were about 90 miles from Midway.

As the cruisers steamed homeward at 28 knots in the dim moonlight, escorted by the destroyers Asashio and Arashio, at 2:15 am on June 5, a lookout on Kumano spotted a surfaced submarine just off her starboard bow, the USS Tambor. Kurita blinkered a 45-degree turn to port to all his ships, Mogami last in line. Her navigator, Lt. Cmdr. Masaki Yamauchi, elbowed his officer of the deck aside and took over the tricky maneuver himself. As he turned, he thought he saw too much distance between himself and Mikuma, just ahead. He adjusted course a little to starboard—and then realized he was not looking at Mikuma at all, but Suzuya. Mikuma lay between the two cruisers, directly ahead of Mogami.

Yamauchi bellowed, “Port the helm … hard-a-port … full astern!” But it was too late. Mogami’s bow knifed into Mikuma’s port side aft of the bridge, crushing Mogami’s bow from the captain’s cabin forward and bending it to port. Mikuma suffered a ruptured fuel tank, leaving a trail of oil.

Mogami had 40 feet of her bow crumpled in. Lt. Cmdr. Masayushi Saruwatari, the cruiser’s damage control officer, dashed forward to find the fore station crew, not knowing what to do and totally disoriented. The Imperial Japanese Navy stressed combat training but was weaker on damage control procedures.

Acting quickly, Saruwatari ordered his men to patch up the holes and straighten out the compartment next to the damaged one. He ordered all possible explosives and inflammables jettisoned overboard, including depth charges and torpedoes, which irritated the skipper, Captain Arika Soji.

When the damage control team was finished, Kurita took stock—Mogami could only do 12 knots and Mikuma was leaking oil. Kurita was in a hurry to rendezvous with the main fleet. He detached Mikuma and both destroyers to escort the battered Mogami and hurried on through the night with Kumano and Suzuya.

Meanwhile, the observant Tambor’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. John W. Murphy, fired off a message to his chain of command, which topped out with Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who was commanding the U.S. fleet off Midway. Spruance took great personal interest in the messages—his son, Edward D. Spruance, was a lieutenant aboard Tambor.

The message also reached Midway, and the atoll’s commanders sortied 12 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and several patrol planes to locate the enemy. At 6:30 am, a patrol plane reported, “Sighted 2 battleships bearing 264, distance 125 miles, course 168, speed 15. Ships damaged, streaming oil.”

Midway sent a squadron of 12 Marine Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bombers under Captain Marshall Tyler to attack. They scored no hits, and on the way down Japanese flak set Captain Robert Fleming’s Vindicator on fire. He dropped his bomb and then, his plane flaming, slammed into the Mikuma’s after turret, exploding the plane.

“Very brave,” was the reaction of Mogami’s Captain Soji, whose ship suffered splinters from near misses. The crash dive started a fire on Mikuma that spread down the intake of the starboard engine room, igniting gas fumes, killing the crew, and reducing the ship’s speed.

Next, eight B-17s under Lt. Col. Brooke Allen attacked the hapless cruisers, scoring one near miss that killed two men on Mogami.

On the flag bridge of the aircraft carrier Enterprise, Spruance weighed the various reports. One of them indicated that the two cruisers were two blazing battleships and a carrier, which meant big game.

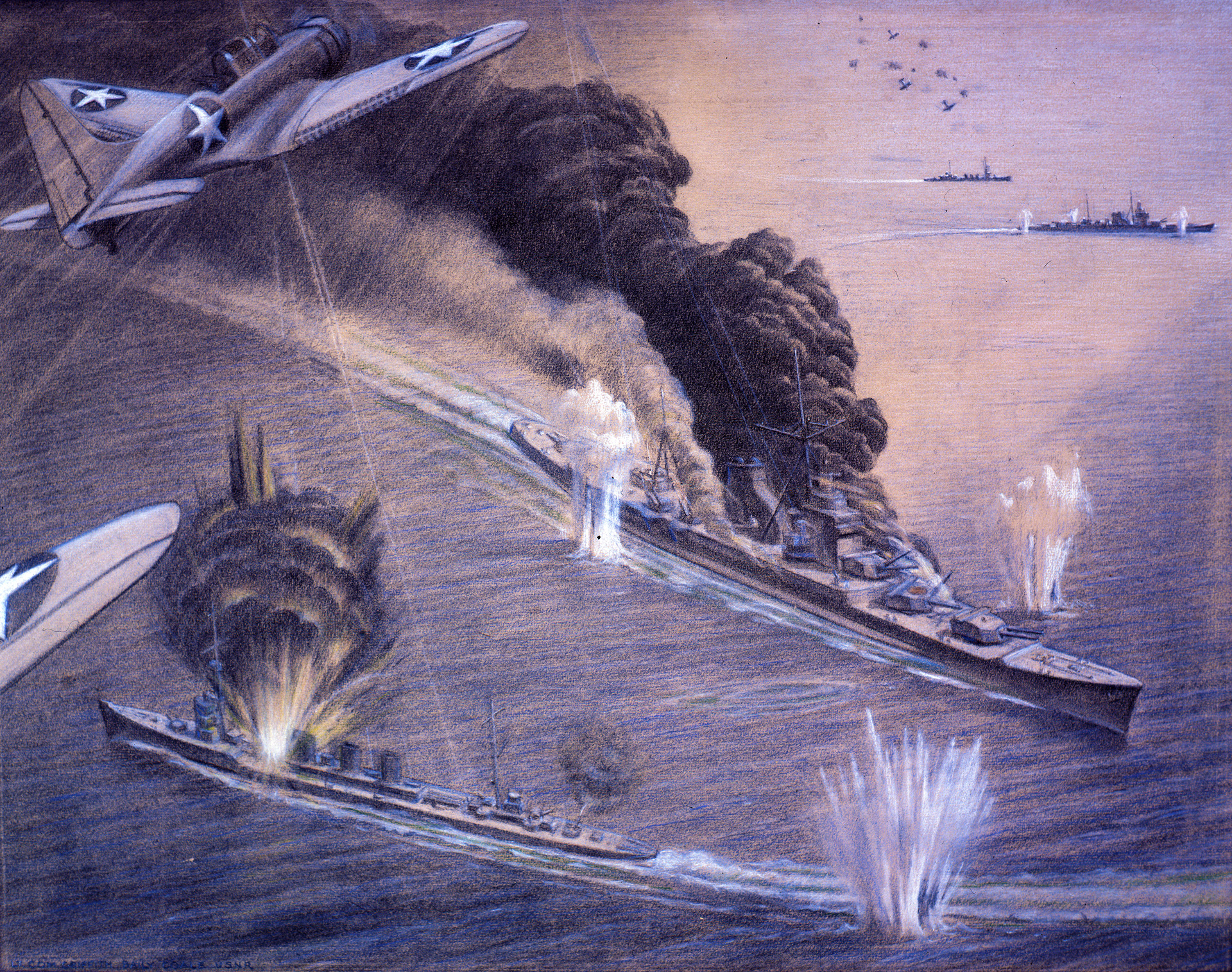

But Spruance was not able to get into position to attack until June 6, and the carriers Enterprise and Hornet hurled 57 dive bombers escorted by 20 fighters to hit the Japanese force. The American pilots reported their targets as 31,000-ton battleships, not the 12,000-ton cruisers they actually were, but were delighted to find the ships barely mobile, putting up little resistance.

American radio frequencies turned blue with excited aviator chatter as the dive bombers swooped down, dropping bombs on Mikuma and Mogami. “Boy, that’s swell. Boy, oh boy. You son of a gun, you’re going up … wish I had a camera along,” one pilot radioed.

Believing Mikuma to be a battleship, the Americans concentrated heavily on her, killing the skipper, Captain Shakao Sakayama, but bombs fell on Mogami as well, punching out her No. 5 Turret, damaging the torpedo tubes, and starting fires below decks.

Saruwatari saw the worst hit of all—a bomb that plunged through the seaplane deck and started a raging fire, incinerating the sickbay full of wounded, doctors, medics, and patients. Unable to control the fire, Saruwatari ordered the entire damaged compartment sealed off, which trapped men inside, leading to their deaths. Saruwatari saw an engineering sub-lieutenant commit hara-kiri. “I trembled with great sorrow,” said Saruwatari later.

The rain of bombs and destruction had immense impact on Mikuma. The executive officer, Commander Hideo Takashima, ordered his men to abandon ship. Despite her wounds, Mogami assisted the two destroyers in rescuing 300 men from the shattered cruiser. But the intense American attack prevented them from pulling 100 to 150 sailors out of the drink. One Mikuma sailor, Lieutenant Masao Koyama, drew his samurai sword and committed suicide on the forward turret. He became a folk hero in Japan, as historian Gordon W. Prange caustically wrote, “by thus assisting the U.S. Navy to kill off promising Japanese naval officers.”

The American attackers left behind a sickening scene of devastated cruisers covered with wreckage and smoke and helpless sailors in the water trying to avoid drowning amid pools of oil. The scene was captured for posterity when Spruance sent Lieutenant (j.g.) Edwin Kroeger in a dive bomber, with Mr. A.D. Brick of Fox Movietone News, equipped to take movies of the destruction. Joining them was Lieutenant (j.g.) Cleo Dobson, who was angry over the immense losses his carrier’s air wing had taken in the battle. Dobson planned to avenge the Japanese strafing of shipwrecked American sailors by doing the same to the Japanese.

But when Dobson arrived at the battle site, he saw that “about 400 to 500 sailors were in the water, all around the ship. After flying over those poor devils in the water, I was chicken hearted and couldn’t make myself open up on them.” Dobson later wrote in his diary, “Boy, sure would hate to be in the shoes of those fellows in the water. I shouldn’t feel so sorry for them, because I might be in their shoes some day. I’ll enjoy reading this when I’m sitting by the fireside and haven’t enough ambition to go out and repeat the performance.”

The resulting photographs were among the most memorable of the entire war, but they irritated Spruance, as he could tell that he had sent a massive force to polish off two battered heavy cruisers, not two battleships and a carrier.

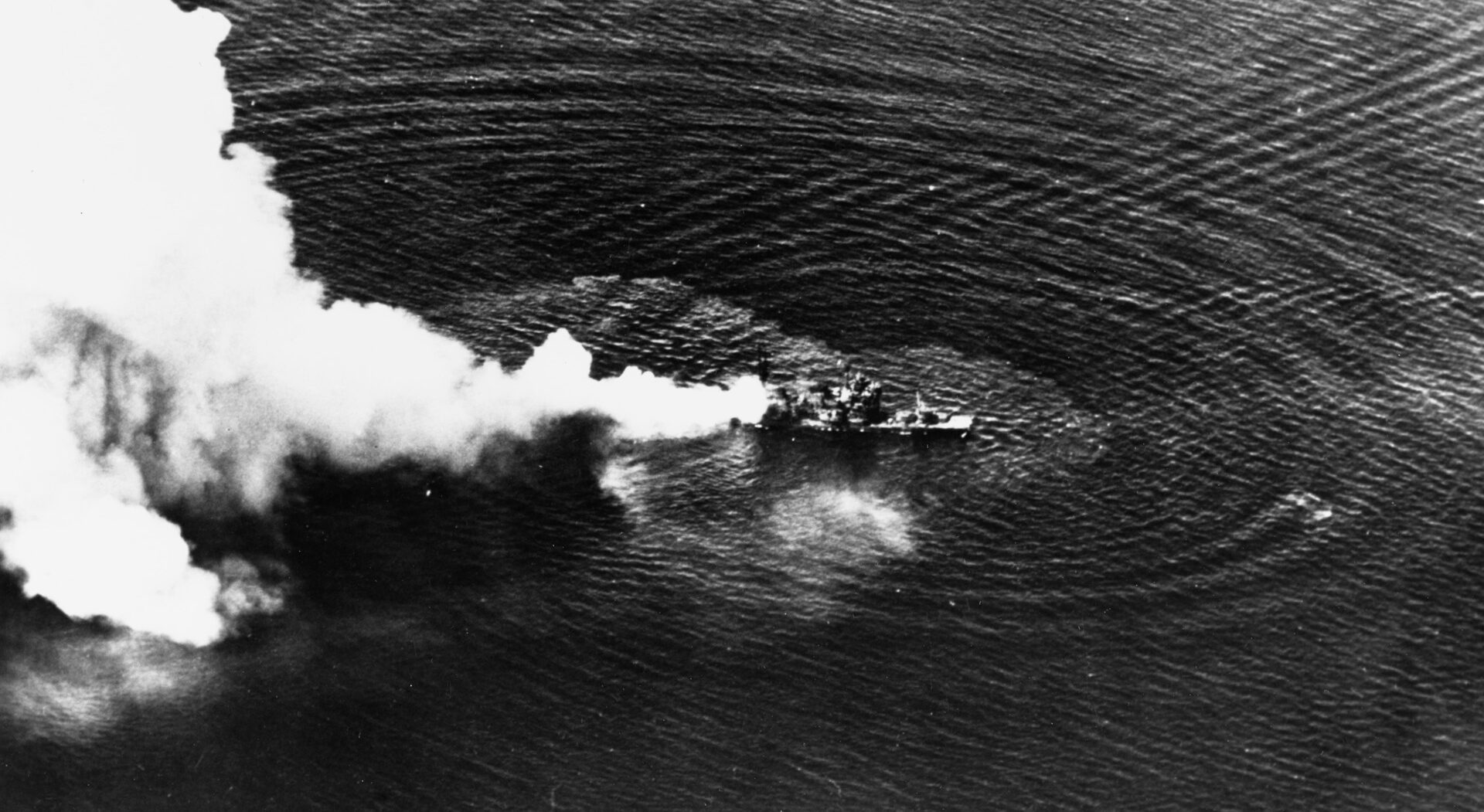

Nevertheless, Mikuma sank shortly after sunset, while Mogami staggered away, having suffered 800 holes and the loss of 90 men killed and 101 wounded. Mogami owed her survival to Saruwatari’s damage control—had he not jettisoned the torpedoes and sealed off key compartments the cruiser probably would have sunk. Battered and burned, Mogami sailed to Truk in the Caroline Islands and safety.

Five weeks of repair work there made Mogami seaworthy enough to head for Sasebo Navy Yard in Japan. The cruiser was in dockyard hands from August 1942 to April 1943, missing the Guadalcanal campaign in its entirety. Her sisters Kumano and Suzuya were assigned to escort the surviving aircraft carriers.

While in the drydock, Mogami had a major rebuild as Japan sought shortcuts to make up for the aircraft carriers lost at Midway.

Mogami’s two aft turrets, one of them destroyed at Midway, were removed, and her aircraft deck extended all the way to the stern. She was given more antiaircraft armament and new air search radar. Now she could carry 11 seaplanes, which could serve as reconnaissance aircraft or fighters. The armored barbettes under the turret rings became bomb stowage areas and gasoline tanks for the seaplanes.

In May 1943, Mogami went back to work, preparing to sail to the Aleutian Islands in response to the expected American landing on Attu. Her bad luck continued. She rammed the oiler Toa Maru on May 22. Mogami was also present in Hashirajima Bay on June 8, when the mighty battleship Mutsu suffered a magazine explosion in her No. 3 turret, sinking her. Mogami launched boats to rescue survivors but found none.

The Americans did not invade the Aleutians in April, so Mogami’s flight deck made her useful in transporting Army troops to Rabaul in July. She was back at Rabaul on November 5, 1943, when planes from the American carrier Saratoga raided the harbor. One of Saratoga’s dive bombers slammed a 500-pound bomb between Mogami’s two forward turrets, starting a severe fire. The damage control men had to flood both magazines, submerging the cruiser’s bow. Some 19 crewmen were killed.

Mogami headed for Truk for emergency repairs, which took a month. She was sent to Kure Navy Yard for full repairs, where she received more antiaircraft guns, for a total of 38. She was in Kure dockyard from December 1943 to February 17, 1944.

Mogami escorted the Japanese carrier fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea but played no role of importance in the engagement. Due to material shortages, she only carried five seaplanes. After the Philippine Sea disaster, Mogami was assigned to the battle line, under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, at Lingga Roads, close to the oil stocks in neighboring Borneo.

When the Americans invaded the Philippines on October 20, 1944, Mogami was assigned to the Third Section of Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura, which was to make up the southern jaw of a nautical pincer counterattack on the American invasion fleet off the island of Leyte. The complex Japanese plan, Sho Ichi Go, or Victory One, called for the surviving carriers to make a demonstration off the Philippines, drawing away the American carriers. Meanwhile, the battleships would slam into the unguarded American transports off Leyte, with one task force steaming through the San Bernardino Strait, the other, under Nishimura, through the Surigao Strait. Nishimura’s task force consisted of two elderly battleships, the Fuso and Yamashiro, flying his flag, Mogami, and four destroyers.

To back up Nishimura’s force, another squadron would follow behind it under Rear Admiral Kiyohide Shima, centered on two heavy cruisers and one light cruiser. The task forces were not coordinated with each other. Kurita took his battleships from Singapore to Brunei, where they refueled and split into their two sections.

Nishimura’s ships steamed for battle from Brunei Bay on October 22 and immediately ran into trouble in the form of air strikes from Mogami’s old antagonist from Midway, USS Enterprise, and the newer carrier USS Lexington. The American air strikes did not impede the Japanese advance but alerted the Americans to Nishimura’s move.

To defeat the attack, Rear Admiral Oldendorf deployed his ships in a vast gauntlet, using the Surigao Strait’s narrow geography to channel the Japanese warships. They would first meet PT boats, then destroyers, and finally a cap of six battleships, five of them Pearl Harbor survivors, four heavy cruisers, and four light cruisers. For Oldendorf, there might have been some personal thoughts in the battle. Mogami had sunk his old command. He had skippered USS Houston in the balmy peacetime years, transporting President Franklin D. Roosevelt on fleet inspections.

Oldendorf’s plan was simple: “My theory was that of the old-time gambler: Never give a sucker a chance. If my opponent is foolish enough to come at me with an inferior force, I’m certainly not going to give him an even break.”

Nishimura’s force hurtled into Surigao Strait shortly after midnight on October 25, 1944, and was immediately spotted by PT boats, which harried the Japanese, reporting their position.

The Japanese used searchlights to try to illuminate their hounds, hurling shells at the nearest pursuers. Neither side scored hits, but the scrapping frayed Japanese nerves. Nishimura was afraid that Mogami would mistake him for the enemy in the deteriorating visibility. Sure enough, at 1:05 am, Fuso lookouts saw a suspicious silhouette off the port bow. Trained to recognize enemy ships but not to distinguish Japanese vessels, they reported the silhouette as American. The battleship hurled 6-inch shells in that direction and got an angry voice-radio message back, “Cease firing, cease firing! Friendly ships!” It was Mogami. Unfortunately, just as the message got transmitted another 6-inch shell hit the perpetually ill-starred cruiser, killing three sailors who were lying in sickbay, wounded in the morning’s American air attack.

Nishimura ordered his ships to cease fire, and the entire Japanese formation regrouped and resumed heading north with the battleships in the lead and Mogami behind.

At 2:11 am, Nishimura shuffled his ships into battle formation for the dash up Surigao Strait. At 2:58 am, the Americans attacked, destroyers loosing 27 torpedoes at the advancing Japanese. The American torpedo barrage was devastating. The torpedoes tore apart Fuso and two destroyers and damaged a third destroyer.

While Fuso turned out of the battle line to sink, Nishimura, aboard Yamashiro with Mogami following him, pressed on, dodging American torpedoes.

At 3:53 am, Nishimura’s force hit the American battle line and felt the full impact of Oldendorf’s big guns. The 16-inch and 14-inch shells from the American dreadnoughts lit up the night and slammed down on the Japanese ships, joined by the cacophony of 8-inch and 6-inch guns from the American cruisers. On Mogami, the American barrage was seen as distant flashes like light rows of a switchboard turning on one after another in a dark room. The light show was followed by the whistle and hiss of incoming shells. Those shells that missed sent up huge walls of white water.

Most of the American shells detonated on Yamashiro, which enabled Mogami to unmask her torpedo tubes.

The Americans did not ignore the cruiser. Destroyers spotted Mogami, illuminated by Yamashiro’s fires, bearing down on the onrushing Hutchins. The destroyers Daly and Bache opened fire on Mogami. On the cruiser, Captain Ryo Toma wondered if he was steaming toward Japanese or American ships in the confusion. To be sure, he flashed two large searchlights and a red Verey star. The Americans answered his signals with a hail of shells. Mogami took a hit on her mainmast, and the steel structure began to sag. Other shells blasted her two radio rooms and antiaircraft mounts. Toma decided to make a wide loop away to try to launch torpedoes from his port side. But the fire and smoke drew a fusillade of 6-inch and 8-inch shells from Oldendorf’s cruisers, which added to Mogami’s pain. Hits were scored on No. 3 turret, knocking it out of action, and on the deck near the starboard after engine room’s air intake, which sent smoke into the engine room, forcing the crew to evacuate. Main lighting failed, and emergency lights clicked on, casting a dull orange glow.

On Mogami’s bridge, Toma and his officers argued over what they should do—continue the attack or withdraw? Toma wanted to withdraw, but his officers believed they could still fight their way past the Americans. Toma yielded to their Bushido spirit. Mogami turned around and headed north at 4 am.

At 4:02 am, two shells from the cruiser Portland smashed Mogami’s compass bridge, and a third tore into the air defense center, killing almost all at both positions, including Toma, his executive officer, Uroko Hashimoto, navigator Nobuyuki Nakano, torpedo officer Konji Uehara, and four more key officers. Lookout Akiyoshi Nishikawa staggered to his feet to find most of the 16 men around him dead and his pal Yoshida missing a foot. Only four signalmen who happened to be on the signaling platform were left alive and standing. Mogami was steaming along out of control, nobody in command.

Chief Petty Officer 1st Class Shuichi Yamamoto, the chief signalman, took the reins. He ran onto the smashed bridge and found the steering mechanism power had failed. He contacted the armored wheelhouse two decks below on the sound-powered phone and called for manual steering and for someone to find the ranking senior officer. Meanwhile, Yamamoto realized he had to make the decisions for the moment and did so, ordering the gutted cruiser to retire.

Shuddering from repeated hits, Mogami swung out of line just as heavy shells slammed into the cruiser’s forward engine room, sending high-pressure steam spewing in all directions, killing trapped engineers. Flames spread to the No. 9 boiler room, and choking black smoke poured out. Boiler tenders shut down the furnace.

At 4:03, another shell knocked out all lights in the port after engine room. Mogami had lost three engine rooms in as many minutes. The engineers in the port forward engine room ignored smoke and heat to provide Mogami with engine power. As the shaking cruiser rattled away, Lt. Cmdr. Giichiro Arai, the gunnery officer, was told he was in command. But with the ship’s guns firing, he could not report to the bridge. Yamamoto would have to keep the conn.

As Mogami retired from the action, American guns and torpedoes sent Yamashiro and Admiral Nishimura to the bottom, capping the last duel between dreadnoughts in history. The Japanese had failed to score a single hit, and the Americans only suffered 39 fatal casualties, 34 of them on the destroyer Albert W. Grant, which was hit by friendly fire. The Battle of Surigao Strait was one of the most one-sided naval victories in history, with Japan losing three destroyers and two battleships.

Mogami, meanwhile, was trying to survive. She and the destroyer Shigure were now the only vessels of Nishimura’s force left afloat, and both were withdrawing. Shigure took an 8-inch shell in her fantail, and her skipper logged “decided to retire.” The battered cruiser and destroyer headed south, and at 4:15 their lookouts were astonished to see a destroyer racing toward them at 30 knots. It was Shima’s lead ship, the Shiranuhi. Behind her was Shima’s flagship, the cruiser Nachi, starting the next phase of the battle.

Shima’s ships advanced through smoke screens. Oil fires blazed on the ocean. The ships passed by the badly damaged and helpless destroyer Asagumo. Then radar spotted two contacts dead ahead at 4:15 am. Figuring it was the enemy, Shima ordered, “All ships attack!” Two of Shima’s four destroyers dashed forward, unmasked their torpedo batteries, and fired their Long Lance torpedoes, which had caused so much havoc in the grueling struggles for Guadalcanal. The torpedoes had eight miles to run.

As it happened, their target was Oldendorf’s flagship, the cruiser Louisville. But the torpedoes missed. Shima and his men peered into the smoke and mist to observe results—and out of the smoke came Mogami, her No. 3 gun turret a ruin, gun barrels blackened, forecastle riddled with holes, flames smoldering from her flight deck aft.

With Chief Petty Officer Yamamoto still on the bridge, the blasted Mogami was retiring at last. Crewmen on Nachi howled banzais of encouragement as the two ships closed the range. On Nachi’s bridge, Captain Enpei Kanooka thought that he would pass Mogami a little too close, figuring that Mogami was dead in the water. But to everyone’s amazement, Mogami was actually steaming along—just barely—and right for Nachi.

Kanooka shouted, “Full reverse!” and right rudder to avoid Nachi’s sister. Too late. At 4:23, Nachi’s anchor deck converged with Mogami’s starboard at No. 1 turret, and the two ships collided with a sickening, jarring crunch. The collision added more dents to Mogami’s battered hide, wrecked Nachi’s No. 2 antiaircraft mount, and ripped a 15-meter gash in Nachi’s port bow at the waterline. Flooding alarms went off, and the two cruisers pulled themselves apart.

On Mogami’s bridge, Yamamoto bawled through a megaphone, “This is Mogami! Captain and XO killed! Gunnery officer in charge. Steering destroyed. Steering by engine. Sorry!”

Shima and Kanooka, exasperated, accepted the blame. Nachi began crawling southward at five knots. Mogami struggled to get in line behind her two sisters. Everyone listened for explosions from the 16 torpedoes fired, but there was no sound.

At 4:35, Shima signaled his destroyers, “Reverse course to the south and rejoin.” The irritated destroyer skippers did so, pulling out of American range.

On Nachi, Shima was assessing the situation. His flagship was damaged from the collision but could still do 18 knots. But it was clear disaster already reigned, as exemplified by the battered Mogami. Shima and his officers conferred. Torpedo officer Kokichi Mori said to Shima, “Admiral, up ahead the enemy must be waiting for us with open arms. Nishimura’s force is almost totally destroyed. It is obvious that we will fall into a trap. We may die anytime. In any case, it is foolish to go ahead now.” Shima got the point. Time to withdraw.

At 4:41, Shima ordered his ships to follow behind Nachi. Hobbling along at 20 knots, they were retreating at a slow speed. On the battered Mogami ammunition started cooking off, hampering repairs and endangering the crew. Because of damaged engine rooms and steam pipes, the fire pumps did not function, and firefighters had to rely on portable pumps and water buckets. Arai ordered his men to jettison torpedoes to prevent them from exploding, but four of them exploded, adding to the smoldering fires. Down in the sole operational engine room, the temperature was hitting 140 degrees Farenheit, and the “black gang” could no longer take the heat.

The crew set the main engine running and evacuated. Incredibly, the engines kept turning, and Arai used hand steering to maneuver his ship.

The Americans pursued cautiously, sinking the destroyer Asagumo. By 5:20 am, the Louisville was eight miles west of Esconchada Point, where Nachi and Mogami had collided an hour earlier. Oldendorf studied the scene through his binoculars and told his column to turn right and prepare to shell the fleeing Japanese with full broadsides.

The “open fire” gongs rang at 5:29, and the Americans hurled more shells at Mogami, scoring several direct hits. To Oldendorf, Mogami was “burning like a city block.” Yet the cruiser survived this latest bombardment, cranking up to 14 knots.

By now, Shima’s weary collection of ships was heading out of Surigao Strait into the Mindanao Sea, enduring further brushes with PT boats. First up was PT-491, which charged Mogami and fired its torpedoes. Mogami hit back with 8-inch shells, and PT-491 retreated.

More PT boats popped out from Shima’s flanks, pestering him with torpedoes, doing no damage but fraying nerves. Edgy lookouts reported bamboo poles as American submarine periscopes.

Shima’s retreating ships awaited the one certainty of the morning—American air attack. Shima radioed for fighter cover but instead received an attack of nine Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and four Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters from the escort carrier USS Santee and two Avengers and six Hellcats from USS Sangamon, launched at 5:45 am. They pounced on Shima’s battered vessels and incorrectly reported them as two battleships. That happened often—Japanese heavy cruisers had massive superstructures and looked like battleships to airmen.

The Americans swooped in to attack. Srafing killed nine and wounded 25 on the destroyer Shiranuhi, and the luckless Mogami took yet another torpedo hit.

Ten Avengers and five Grumman FM-2 Wildcats from USS Ommaney Bay came next, storming down on the smoking Mogami, scoring two more hits and starting fires and bringing the ship to a halt. The destroyer Akebono sprayed water on the cruiser. The men evacuated Mogami’s No. 2 engine room, finding the ladder and hatch red hot. Everyone but the antiaircraft crews fought the fires.

The American bombs smashed into the cruiser’s oil tanks, setting them ablaze. Gunnery officer and acting commanding officer Arai ordered the three forward 8-inch magazines flooded to prevent an explosion, but the warped bulkheads meant that the valves for No. 1 gun room would not open. The cruiser was blazing and could sink at any moment.

In tears, Arai ordered his men to abandon ship at 10:30 am. With her davits broken, Mogami could not use her cutter, so Akebono closed Mogami’s port quarter to take aboard the cruiser’s crew.

On Mogami the exhausted crew mustered topside on weather decks to abandon ship after three hours of desperate fire fighting, shuffling aboard Akebono. At 12:56, Akebono fired a Long Lance into Mogami’s port side, and the cruiser began to sink, her demise hastened by an explosion in No. 1 magazine. At 1:07, as her crew stood by on Akebono, watching and crying, Mogami slipped beneath the waves.

The cruiser had performed bravely in her final battle, enduring the loss of her skipper and senior officers, withstanding more than 100 shells of various calibers, its own torpedoes exploding, three bomb hits, and a collision. All but 20 officers, 171 enlisted men, and one civilian of Mogami’s 850-man crew were saved by Akebono.

Nachi lasted a little longer, steaming to Manila. En route, she suffered an American air attack on October 29, which did little damage but added to her indignities and pain.

At Manila, Nachi was shoved into dock No. 103 to have her flooded bow drained and damaged plates repaired. That was accomplished by November 2.

On November 5, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s Task Force 38 pounded Manila with four waves of airstrikes. With her fleet commander, Rear Admiral Shima, ashore for a conference, Nachi got underway after the second wave, but at 12:50 pm she was caught between Manila and Corregidor and immobilized by bomb hits and torpedoes in the starboard boiler rooms. A distressed Shima watched from the beach as American bombers tore apart his flagship.

Akebono sprinted to help the ailing cruiser, but the fourth wave caught both ships, and five aerial torpedo hits were scored on the cruiser. Nachi sank at 2:45 pm, taking 807 men to the bottom of Manila Bay with her, including her skipper, Captain Kanooka, and 74 members of the 5th Fleet staff. Barely 220 men survived the sinking and follow-up strafing. Akebono was hit by two bombs and set afire but was dragged to safety ashore with the loss of one officer and 23 men killed.

Nachi’s wreck, however, was of great interest to the U.S. Navy. In March 1945, after the liberation of Manila Bay, the submarine rescue ship USS Chanticleer, under the command of Lieutenant Luther Leroy Tyndall, a 39-year-old former Navy boatswain, anchored near the wreck.

Nachi had been a flagship, and that meant she was probably a major source of intelligence. From April 14 to May 7, 1945, Chanticleer conducted daily dives on the wreck, scouring the hulk for intelligence.

Chanticleer’s top diver, Joseph Sidney Karneke, made the first descent, landing on the cruiser’s mast. He headed toward the bridge and came upon an antiaircraft gun tub fully manned by Japanese skeletons. Shocked but undeterred, Karneke headed for the bridge and found stacks of charts spread out on the chart table and documents in drawers and on shelves. The Office of Naval Intelligence ordered Chanticleer to pull up everything of interest from the Nachi.

The divers found plenty, hauling up 20 mailbags full of sodden paper. They picked Nachi’s charthouse clean, including Shima’s flag plot. They found a complete set of blueprints for Nachi, which enabled divers to plot a systematic search plan. The blueprints were invaluable—one dive only succeeded because the divers followed the path created by a 1,000-pound bomb that penetrated four decks down.

There were some blunders. Karneke found a safe, and Tyndall was determined to haul it up. Karneke had coal mining experience, and he used a plastic explosive charge to crack the safe open. When they did so, it turned out the safe contained no secret documents—just packets of Japanese currency used by the Fifth Fleet to meet the payroll, as much as two million yen in bank notes and coins. Chanticleer crewmen were able to give pals 10-yen notes as souvenirs. Another locked compartment turned out to contain nothing but rice bowls, which led divers to joke that the Japanese Navy left its secret documents out but locked up the rice bowls.

Nevertheless, the haul was immense, keeping a platoon of Japanese translators working. It included copies of the directive to attack Pearl Harbor, which was used at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials as the basis for the prosecution.

Also brought up were Japanese Navy regulations, standing orders and doctrine for Japanese carrier units, the manual for Japanese destroyer antisubmarine warfare, orders from the Combined Fleet command on fleet tactical doctrine, charts of mined waters, lessons-learned reports on previous battles, vast copies of Japanese Navy fleet operations orders and plans from Pearl Harbor to Leyte, Nachi’s ship’s logs from as far back as 1937, the cruiser’s radar set, and even samples of Japanese infrared and ultraviolet signal lamps, which were unknown to American intelligence.

While the intelligence haul came very late in the war—after most of the Imperial Navy had been destroyed and before the atomic bombs—had the U.S. been required to invade Japan the information would have been extremely useful for coping with the Japanese Navy during the assault. As matters developed, they became useful to historians.

Had Mogami not collided with Nachi that morning in Surigao Strait, Nachi would not have had to turn aside to Manila Bay for repairs and been caught there by Halsey’s planes. So the intelligence coup for the Americans was yet another major millstone around Mogami’s neck. Her career of failure had ended with an even bigger failure.

Also liberated from Nachi’s hulk was Vice Admiral Shima’s flag, which drooped from her masthead just before the wreck was dynamited as an obstacle to safe navigation. It was the only case in World War II of an enemy admiral’s flag being taken from a warship at sea, and because Nachi’s demise was a direct result of the collision with Mogami it added one final embarrassment to Mogami’s ill-starred career.

New Jersey-based author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written on numerous topics, including other battles of the Pacific War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments