By Kevin M. Hymel

“You’re crazy to go out there!” a paratrooper shouted to medic Al Mampre as he bolted from a trench outside of the Dutch town of Eindhoven. But Mampre had his mission, and he knew what needed to be done.

When he reached Lieutenant Bob Brewer, who was sprawled out in a field, he sat down next to him. “I’ll take care of you,” he told the wounded officer. A sniper’s bullet had gone through Brewer’s neck below his chin. He was unresponsive and jaundiced. Despite the severity of the wound, it did not bleed much. Mampre sprinkled sulfa powder on the wound and covered it with a bandage. After struggling to find a good vein in Brewer’s arm, he injected a plasma needle and held the IV bottle aloft.

Another medic sprinted out to join Mampre. Then shots rang out. The German sniper, occupying one of four houses across the field, had targeted the three Americans. Mampre heard what sounded like a bottle breaking and looked up at the IV, but it was still whole. Then another bullet clipped the other medic’s heel, and he took off for the safety of the trench. Bullets kicked up dust around Mampre and Brewer. Three other paratroopers dropped around them, victims of the sniper’s aim.

Then Mampre felt like a mule had kicked him in his left leg. “My leg was opened up like a roast beef,” he said, but, like Brewer’s neck, his leg did not bleed badly. “I could see the bone.”

Mampre gave himself a shot of morphine and then lay down next to Brewer and in his best bedside manner asked, “Lieutenant, are you dead? ‘Cause if you’re dead, I’m leaving.” “No,” Brewer whispered, “but I don’t know why not.” As bullets stitched the ground, Mampre told Brewer he would stay with him.

The two men were in desperate straits. It was their second day of combat in the Netherlands. They had parachuted into the area the day before, September 17, 1944, as part of Operation Market Garden, the Allied attempt to cross the Rhine River with a combined armored and airborne force. Mampre had once been a part of Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, but had been promoted to battalion medic before departing for Europe. Now, on his second day in combat, he found himself a casualty treating another casualty.

The war started for 19-year-old Mampre when he heard that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, while he was listening to the Redskins-Giants football game on the radio. “I didn’t really realize the impact,” he said. Mampre, from Oak Park, Illinois, was a ministerial student at Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas. A few days later, his church minister told him his studies would prevent him from being drafted. “That didn’t sound right to me,” he said.

In the spring of 1942, Mampre enlisted in the U.S. Army in Dallas but soon discovered he was not a rule follower. He liked wearing his overseas cap straight on his head. When his drill sergeant would shout, “Tilt that hat sideways!” Mampre did so, but straightened it out when the sergeant walked away. He often found himself scrubbing pots or handing out ice cream. This was not the Army he imagined. “I want to do something,” he told himself. “I want to be a paratrooper.” So he volunteered for the paratroopers and soon found himself on a train headed to Toccoa, Georgia.

Mampre joined the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which had just been formed. Its commander, Colonel Robert Sink, proved to be a no nonsense soldier who wanted his regiment to be the best in the Army. When Mampre scored in one of the regiment’s top three on a test, Sink told Mampre his standing, but added, “I have other news for you: you’re not going to leave this outfit until you die.”

On his first day at camp, Mampre and fellow private Edwin Pepping came across a 35-foot jump tower. They decided to test their skills, so they climbed the tower and threw themselves off. Both landed unhurt despite hard landings. Just then a lieutenant walked up and explained that the tower still needed the cables for paratroopers to slide down safely because the tower was designed for practicing door exits, not landings. “Dumb, dumb, dumb,” said Mampre about the jump. “I thought they got handed all the dumbest guys, and they put them in the same regiment.”

Mampre was soon assigned to Captain Herbert Sobel’s Easy Company. Sobel, like Sink, wanted his company to be the best in the regiment. To achieve that goal, Sobel trained his men constantly, even when other company commanders gave their men time off. “The only trouble with Sobel,” said Mampre, “was he couldn’t read a map and couldn’t find his way out of a paper bag.”

Mampre took to the hard training immediately. Paratrooper candidates were required to run a three-mile route up Currahee Mountain and back. The first time Mampre did it, he went up with 90 other soldiers and came back with just six. At 5-6 and a wiry 122 pounds, he considered himself a tough son of a gun. “You don’t worry about the little guys,” he liked to say.

Mampre’s training included tear gas drills, target practices, and foot marches. On one march, Sobel ordered the men to crawl over pig entrails. “We slept in that stuff that night,” he said.

One day at the firing range, Mampre bet another private a candy bar he couldn’t hit the target. The soldier took aim with his rifle and hit it. Mampre made the same offer, and he again hit the target. They kept going. “I figured sooner or later he’d miss,” said Mampre. He didn’t. By the end, Mampre owed the soldier eight candy bars. The soldier turned out to be Private Darrell “Shifty” Powers, considered by many to be the best shot in the company.

When the regiment formed a medical detachment, Colonel Sink asked Mampre if he would like to be a medic. Mampre said yes and joined with Pepping. The two developed a knack for obtaining anything they needed without going through proper channels, calling themselves the “Band-Aid Bandits.” Both men considered medical training similar to what they learned in the Boy Scouts. The main difference: the medic candidates practiced giving shots to oranges. “I never ran into an orange in combat,” Mampre mused.

After Mampre and Pepping received their medical certifications, the regiment assigned a new lieutenant to toughen up the medics. He started off by teaching them to properly salute. In retaliation for the senseless exercise, Mampre lit a can of photo film on fire in his barracks. As smoke filled the room, Mampre ran outside to the lieutenant, shouting, “They’re trying to kill us!” The lieutenant went into the barrack and threw the burning can outside, telling Mampre, “I don’t think you’re gonna get killed.”

The next day the lieutenant asked Mampre what the paratroopers did. Mampre told him, “Run the mountain.” The lieutenant agreed and joined the medics for the seven-mile run (it was a half mile to the base of the mountain). Mampre was charging up the slope when he noticed the lieutenant running out of steam. “Check the rear!” the lieutenant ordered. “Don’t need to!” Mampre shot back. The lieutenant decided he would. “See you at the obstacle course,” said Mampre, hinting at more exercise later. Eventually, the lieutenant made it up Currahee. “He turned out to be very nice,” Mampre recalled.

While the training honed the men’s physical skills, it stimulated voracious appetites. One day, Mampre and his fellow medics caught the smell of fresh muffins wafting from the cook house. They found the tray of muffins and grabbed it, but not before the cooks grabbed the other end. The tug of war ended when the Military Police showed up and took down everyone’s names. “One guy said his name was ‘John Smith,’” explained Mampre, “another said ‘Terpin Hydrate,’ which means cough syrup.” Later, Mampre and his comrades snatched a line of milk bottles laid out for the battalion’s officers. “We were growing boys,” he defended, “we needed them.”

The medics drank more than milk. They often drove to local watering holes in an ambulance. Mampre would sit up front with the driver and Captain Samuel “Shifty” Feiler, the dentist, between them. When they reached the bar, someone would shout, “Last one out buys!” and everyone poured out. Mampre and the driver made sure they opened their doors last, ensuring Feiler, stuck in the middle, paid.

Before leaving Toccoa for more training, Colonel Sink picked Major Robert Strayer’s 2nd Battalion, composed of Dog, Easy, and Fox Companies, to march 115 miles to Atlanta in three days on December 1, 1942. The battalion marched mostly through back roads, eating cheese sandwiches from food stations.

Mampre spent most of the march treating foot problems and running to catch up with Easy. He recalled that water froze in the canteens, and men relieved themselves without stopping. When the three-day march was complete, he became the noncommissioned officer medic for the entire battalion, and he took part in a second march with Major Oliver Horton’s 3rd Battalion from Atlanta to Fort Benning. Mampre was in excellent shape.

After the marches, the regiment moved to Fort Benning for parachute training. Once Mampre completed his ground training, he and 23 other candidates parachuted out of a Douglas C-47 Skytrain. While he had no problems, one or two other candidates got sick in the plane. The hardest jump was the last, a night jump. “You couldn’t tell the difference between the Chattahoochee River and the highway,” said Mampre. “One guy who jumped,” he recalled, “didn’t remember jumping.” Mampre never feared and felt that he would never die. He completed the required five jumps to receive his jump wings.

With his initial five jumps completed, Mampre and the rest of regiment transferred to Camp Mackall in North Carolina to continue training. There he perfected his jump technique: turning on his back so he could look up at the plane to see if the equipment had been released from the fuselage. He also perfected coming down fast by pulling down hard on his risers, four straps that extended from the parachute down to the harness strapped around his torso. By pulling all four risers he reduced the amount of parachute catching air, accelerating his descent. At the last second, before hitting the ground, he let up on the risers, fully inflating his parachute and breaking his descent. “I always landed standing up.”

On one windy jump, Mampre landed and quickly collapsed his chute to keep from getting dragged across the drop zone. Another paratrooper was not so lucky. “There was another guy being dragged in a full-blown chute and making dust.” Mampre jumped on the man’s chute and began chewing him out for not collapsing it quickly enough. Mampre was in the middle of his curse-filled tirade when he wiped the dirt off the man’s face, revealing Major Oliver Horton. “He just grumbled,” said Mampre.

In June 1943, Sink’s 506th headed to Tennessee for large-scale maneuvers, where Mampre and his medical crew had some fun. During a night exercise, one of the regiment’s doctors declared Captain Sobel—who most of the men considered a martinet—a casualty. Mampre and some other medics carried him back to a makeshift operating area while Sobel declared to anyone in earshot, “Look at me! I’m a casualty!” On the operating table, the doctor put Sobel under and then painted his abdomen red, scraped him with a scalpel, put in superficial stitches, and covered the spot with a pressure bandage.

The medics then brought in Lieutenant Jerre Grosse, a mustachioed officer who was scheduled to be married. After putting him under, they put his arm in a cast and shaved off half his mustache.

The medics put both Sobel and Grosse under a truck to recover. Mampre laid down between them to ensure their safety. Sobel woke up first and felt his pressure bandage. Then he looked down at his red abdomen. Shocked, he screamed out repeatedly to the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Strayer, “They operated on me!” Strayer simply laughed.

Sobel quickly recovered from the prank. The next day at a regimental review, he led Easy Company in mass formation while he counted cadence and hollered, “Hi-ho Silver!” Grosse also recovered. He simply broke off his cast and shaved off the other half of his mustache. His fiancée preferred him without it.

After additional training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Mampre and the rest of the regiment headed north to New York and boarded the RMS Samaria.After an uneventful trip across the Atlantic, the ship pulled into Blackpool, north of Liverpool, on September 15, 1943. As Mampre and the other troopers crowded the ship’s deck, a flight of British Supermarine Spitfire fighter planes flew in low to greet the Americans. “It was a terrific sight,” he recalled.

The regiment headed by train and truck to Aldbourne, west of London. Along the way the men heard Axis Sally on the radio welcoming the 101st Airborne Division—whose trans-Atlantic journey was supposed to have been secret—to England.

Once in Aldbourne, the unit continued to train and conduct air drops. At one training range, where men walked through pop-up targets, crows started landing in the trees. The paratroopers opened fire without hitting a single one. The scene made Mampre think, “We’re going into combat and we’re in trouble.”

Despite the intense training, the medics managed small rebellions. One medic, a cook, smuggled some local girls into a stable. Mampre and Lieutenant (Dr.) Jackson Neavles, the battalion surgeon, went to the stable where Neavles ordered the cook out. When he didn’t respond, they threw in colored smoke grenades. The girls ran out crying, their faces streaked with colors. “Those girls had to walk back to Swindon [about five miles away] like that,” said Mampre. The cook, on the other hand, refused to come out.

Other medics had their own way of doing things. They dyed their hair with medicinal peroxide, turning them all blond or shades of red. When their hair grew back, leaving them with dual hair color, their British hosts did a double take. “They thought it was all the rage back in the U.S.,” said Mampre.

From time to time during the war, Mampre received letters from Virginia Jobul, a girl he knew while growing up. She lived in Evanston, Illinois, and they had dated a few times before he left for college. He enjoyed her letters but that was all. “Most of us didn’t think we should burden a girl with that,” he said.

Possibly the most memorable incident at Aldbourne was the clash between Captain Sobel and Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Winters, the company’s executive officer. On October 30, Sobel accused Winters of ignoring an order, and Winters requested a court-martial due to the fact that he never received the order. As tensions mounted, Lt. Col. Strayer transferred Winters to the battalion mess. Sobel’s actions infuriated most of the NCOs, who jointly wrote letters to Sink demanding he either replace Sobel or they would turn in their stripes. “They thought we were gonna mutiny,” Mampre said of the battalion staff’s overreaction. “The regiment posted a machine gunner on the street. That made me mad.”

Sink ended up transferring Sobel out of the company and replacing him with Lieutenant Thomas Meehan, and Winters returned to Easy Company to lead 1st Platoon. “Winters was firm but fair,” Mampre said of the man who would eventually command Easy Company in its initial combat.

On March 23, 1944, Mampre jumped with the regiment’s 2nd and 3rd Battalions for General Dwight D. Eisenhower, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley. Mampre boarded a C-47 with a calico cat and a homemade parachute. He tucked the cat and chute into his musette bag. When the green light went on, he charged out. Once his parachute inflated, he pulled the cat out of his bag, but the parachute slipped off and floated away. He quickly stuffed the cat back into the bag. After he landed, he went to pull out the cat, but, as he remembered, “the cat was all claws.”

About 10 days before the June 6 D-Day drop, Mampre developed a painful cyst that almost circled his neck. A major ordered him to the hospital where surgeons removed it. While the surgery was successful, Mampre missed the invasion of France. When he learned about the airborne assault, he felt terrible. “All that training for nothing!” he lamented.

Mampre recovered and returned to an empty Aldbourne, but he was not alone for long. His brother Edward, with the Eighth Air Force, showed up, and the two brothers enjoyed a reunion. Edward gave Al a flight jacket, which he cherished.

One night they were out together when Mampre spotted a colonel and said, “Let’s see if this guy’s on the ball.” Mampre gave the colonel a sharp salute with his left hand. The colonel immediately called him back, then pulled Mampre’s left hand and poked it with his finger. “That’s your left hand,” he declared before poking his right hand, “and that’s your right! That’s the one you salute with.” The colonel was evidently on the ball.

Finally, after almost a month of fighting in France, the regiment returned to Aldbourne. The men continued to train for their next combat jump, which never seemed to come. The Allied armies in France were driving too quickly and planned drops were canceled.

One day a request came in for volunteers to jump into Poland, where the Poles were liberating Warsaw before the Soviet Red Army arrived. “We were gonna jump into the woods,” said Mampre. Unfortunately, the Soviets halted at the Vistula River, allowing the Germans to crush the Warsaw rebellion. The mission never happened.

But the next one did. The entire division was alerted for Operation Market Garden, the Allied effort to jump the Rhine River in Holland, where it became the Neder Rhine. The 101st Airborne had been slated to capture the cities of Eindhoven, Son, Veghel, and Grave, ensuring the bridges in all locations were intact for advancing British armored forces. The daylight drop was scheduled for September 17.

Although Mampre did not pack a weapon, he weighed himself down with surgical equipment, including two canteens of ethyl alcohol. Being bowlegged, he strapped equipment between his legs. Once loaded up, he had trouble moving under his burden. “I had to be pushed up into the plane,” he recalled. His C-47 took off and headed to its drop zone, while Mampre napped for part of the flight. As the plane reached the drop zone, Mampre saw Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter planes strafing the field.

Then the order came: “Stand up and hook up!” barked the jumpmaster at the door. When a green light by the door lit up, Mampre charged out with the rest of the men. As he jumped, he saw a blue sky before him and a freshly plowed field beneath him. “It was a nice clean jump,” he said. But it did not last long.

Mampre was about 75 feet from the ground when a fellow paratrooper fell into his parachute and collapsed it. Mampre dropped like a missile and landed hard. The paratrooper landed on top of him, jamming his rifle butt into Mampre’s chin. “Where’s the enemy?” the paratrooper called out once he got his bearings. An irritated Mampre responded, “You’re standing on him!” It was the first time Mampre did not land on his feet.

Mampre had volunteered to jump with a center-release chute button on his chest. He hit it, and his parachute straps fell off. Men hustled off the field while clouds of colored smoke designated the different assembly areas. Mampre soon heard another paratrooper call out, “I can’t walk!” He painfully walked over to the man, shot painkiller into his leg, gave him a swig from his medicinal canteen, and told him to follow the blue smoke to his group.

As the paratroopers headed to Son, Mampre noticed well-dressed locals waving flags. Suddenly, an enemy machine gun opened up, and Mampre quickly took cover in a doorway. He noticed a woman’s hand out of the corner of his eye. “This woman was feeding me cherries,” he recalled. When the machine gun stopped, he took off, never having seen the woman or thanking her.

As Mampre raced through the town, he heard a vehicle engine failing to start. He hustled over to a backyard and spotted a German jumping over a fence, leaving a small pickup truck. Mampre found Easy Company’s medic, Private Moore. “He could fix anything,” said Mampre. Sure enough, Moore started the vehicle, which was used by the paratroopers throughout the Netherlands.

The Germans had destroyed the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal, the 506th’s objective, forcing the regiment’s engineers to improvise a footbridge. By the time Mampre crossed, it was getting dark. He bedded down in a barn. When he woke the next morning, he realized he was next to a huge pig. “If the pig had rolled over me, I would have been flattened,” he said.

The 2nd Battalion paratroopers headed to Eindhoven through a lightly wooded area that ended at an open field. Across the field stood four houses. Mampre watched as Easy Company riflemen walked ahead of him. Someone called out, “Medic!” and he asked the battalion surgeon, Lieutenant Neavles, “Why are they calling for a medic? They have four medics in Easy Company.”

He hurried forward to the wood’s edge where several paratroopers occupied a trench. They pointed to an officer sprawled in a field. It was Easy’s 1st Platoon leader, Lieutenant Bob Brewer. Mampre went out to help him. That’s when a German bullet hit him in the leg and wounded the three other paratroopers.

As the five men lay in the field with bullets popping all around, a group of Dutch civilians ran to them carrying a ladder. They pulled Brewer onto the ladder while others treated the four Americans. Mampre gave them his bandages and sulfa powder to treat his leg. One of the civilians picked up Brewer’s M-1 carbine and emptied the entire magazine at the house bearing the German sniper. The civilians helped the wounded to their feet.

Mampre worried when the civilians led the small group toward the same houses as the German sniper fire. As they neared the second house from the left, a woman standing nearby shouted, “Tote!”—the Dutch word for “dead.” Mampre didn’t know if she was talking about the German sniper or a relative of hers. Then Easy Company’s Sergeant Myron Rainey called out to Mampre, who was hobbling on his own, “We got ‘em!” The sniper, who had been in the fourth house, was dead.

The civilians brought the Americans into the house, where Mampre was first struck by its clean, immaculate floors. Then he was struck by the urge to throw up, a common reaction to morphine. He quickly made eye contact with a woman, made a circle with his hands, and pointed at his mouth with the expression that he was going to get sick. She understood and got him a bowl. “I’m not going to dirty her floor,” he recalled.

Once everyone was treated, they brought the Americans outside and put them in a cart. Some of the Dutch did not want the Americans to leave, but Mampre wanted to get back to his unit. A Dutch doctor wanted to go to Eindhoven, but Mampre wanted to head to Son where he knew there was a division aid station. The discussion ended when the Germans opened fire on the group. The Dutch hauled the cart toward Son, while Mampre dropped headfirst into a German foxhole. Some Dutchmen pulled him out and threw him onto the wheelbarrow, delivering him to Son.

Mampre arrived in time to see the tanks, trucks, and infantry from the British XXX Corps streaming thought the streets, bumper to bumper. Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery passed by in his staff car, waving to the crowds, but Mampre was not impressed. “He looked like death warmed over,” he recalled. At exactly 4:30 pm, the British stopped to brew tea. Mampre was shocked. “What are you doing!?!” he shouted at the Tommies. “There are Germans all over here!”

Mampre was brought to a hospital where, surprisingly, he gave a pint of blood. He was then sent to a mobile hospital in Belgium, where he complained of a constant stinging pain in his inner right thigh, which no amount of scratching cured. Then he noticed two holes in his pants. The doctors found a bullet hole in his right groin. They cleaned it, operated, and sewed him up.

Next, Mampre was sent to a hospital in England. There, he returned to his rebellious ways, sneaking out a window, on crutches, to play golf on a course where red- and blue-painted sheep were grazing, trimming the lawn. Mampre tried unsuccessfully to hit them with his golf ball. Whenever he finished a round, the course owners treated him to a glass of scotch.

Mampre, as a qualified paratrooper, thought he would be returned to his regiment but instead was sent to a replacement depot, known to the GIs as a Repple Depple. “They hated paratroopers,” he said of the officers there. One staff sergeant had put an 82nd Airborne Division paratrooper on kitchen patrol (KP) duty every morning. Mampre told him not to go and went to the officer in charge, a Colonel Killian, to end the matter. “You’re sending this guy to the kitchen all the time,” Mampe demanded, “use another guy.” Mampre later learned that Killian had been court-martialed.

Life at the Repple Depple was not all bad. Mampre was put in charge of the other replacements and would take them on five-mile marches. After leading the soldiers around a bend out of sight of the officers, he stopped them, then ordered two men to buy tickets to the camp movie house. The men would then take in a show.

Mampre finally made it to Mourmelon, France, near Reims, on November 29, 1944, where the 101st had set up camp. While there, he and his comrades took advantage of the regional ambrosia. The owners of Pommery’s Champagne House in Reims told him they had champagne but no bottles, so he explored some old World War I trenches and found more than 100 empty bottles. He had his fellow paratroopers hook up a trailer to a jeep before driving it to Pommery’s. “I had enough champagne for the rest of my life,” he recalled.

Mampre also returned to his Band-Aid Bandit ways. He and some medics decided to steal an armoire from the upper story of an officers’ barracks. Mampre attached ropes to the armoire and was lowering it out a window when a lieutenant walked up and asked, “What are you doing?” Mampre told him he was trying to haul the armoire up to the room. Seeing that Mampre was about to be yanked out the window, the lieutenant told him to lower it and departed. Mampre and his buddies had a new armoire.

In need of a shower, Mampre went into the officers’ shower but, while he was showering, an officer came in and asked, “Lieutenant?” When Mampre didn’t answer, the officer asked, “Captain?” Mampre finished, wrapped himself in a towel, and as he left said, “No. Staff Sergeant, but I’m clean.”

While there he saw some washing machines in crates. He “borrowed” one and had his fellow medics dig a square into the ground to hide it. The medics looked cleaner than the rest of the regiment. “Colonel Sink was wondering what was going on,” he said.

Mampre enjoyed his time in Mourmelon until December 18, when the entire division was put on alert. Two days earlier, the Germans had broken through the lines in Belgium and Luxembourg and were pressing west—the Battle of the Bulge. The paratroopers gathered what equipment they could and loaded onto trucks for a day-long journey east. Before Mampre climbed on board his truck, he reported to the hospital. “We found a washing machine in our area,” he told someone in charge. “Good,” the man replied. “We’ve been looking for it.”

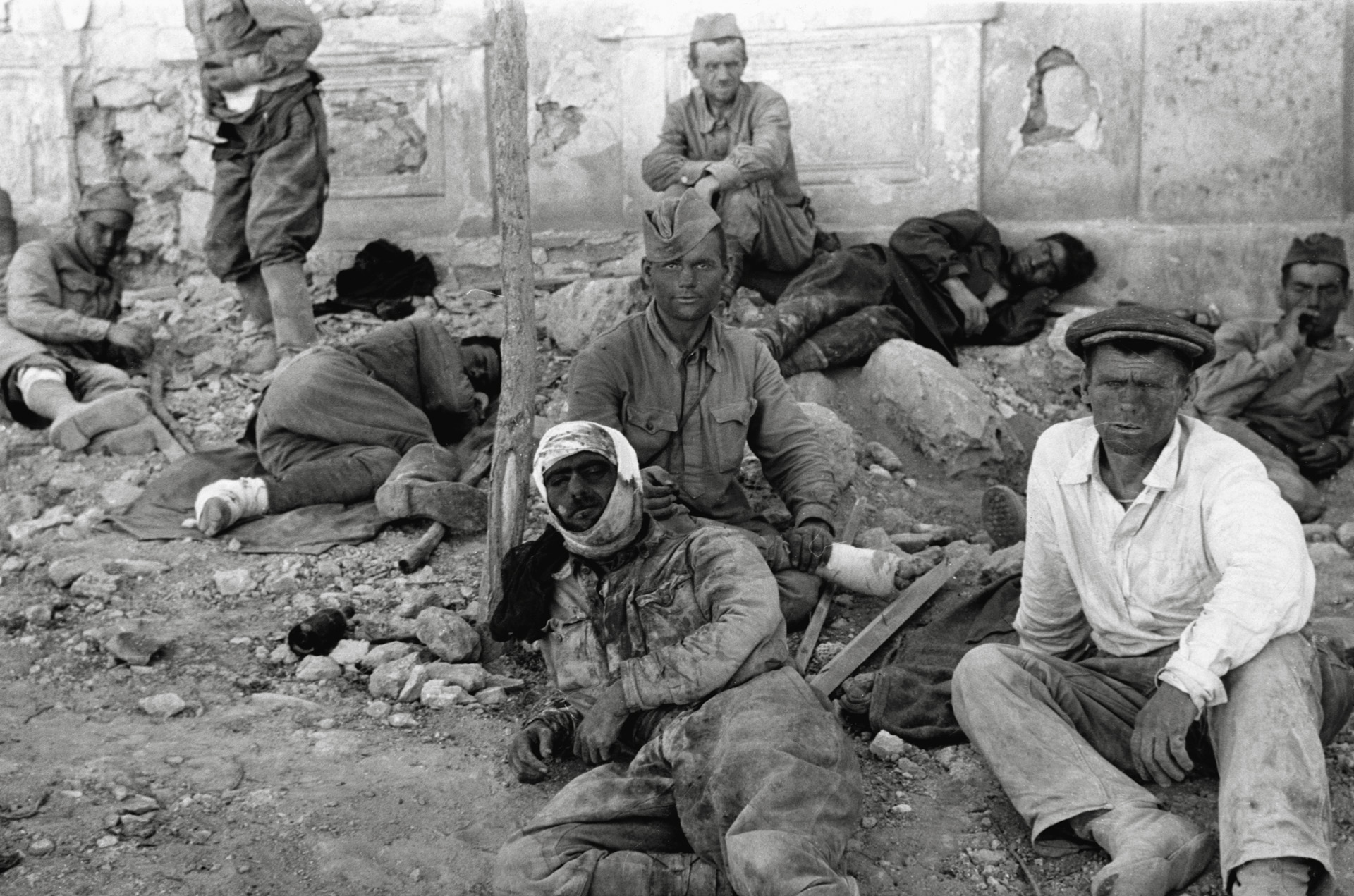

A long caravan of trucks took Mampre and the rest of the division to Bastogne, Belgium, where elements of the 10th Armored Division, as well as scratch forces of the 9th Armored and 28th Infantry Divisions, desperately held the north, east, and southeast approaches to the town. As Mampre’s truck made its way into the town, he was shocked to see haggard American soldiers staggering to the rear. “It still haunts me,” he said, “seeing files of Americans going the other way, telling us not to go there—and we’re going in there.”

Once in Bastogne, Mampre saw MPs directing traffic through the town’s center as artillery shells rained down. Mampre arrived at an Army barracks where Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the acting division commander, had set up headquarters. Mampre was assigned to the regimental aid station located across from McAuliffe and began receiving wounded.

As Mampre worked on badly wounded men in Bastogne, time became a blur. He remembered men bringing in a young paratrooper named King, who had been killed accidentally by a strafing P-51 Mustang fighter plane. “A .50-caliber bullet was still in his chest,” he said.

Another paratrooper with his arm torn off all the way to his shoulder lamented losing his watch. Yet another paratrooper had been shot in the head, but the bullet entered his helmet, tore through his helmet liner and exited the back without injuring him. One soldier had been hit in the helmet by a mortar shell that exploded. Again, it did not injure him.

Mampre experienced the same kind of luck when an artillery shell landed in front of him outside his makeshift hospital. It hit the ground and broke apart without exploding. Mampre simply looked at it and thought, “That’s a really big shell.” Yet the incident had little effect on him. “I never thought I could have been killed,” he later said.

Mampre was often impressed with the medical staff as well as the paratroopers around him. Captain “Shifty” Feiler, the dentist who often had to pay for drinks back in Toccoa, treated 1,000 wounded and frostbitten men by himself, the most in the regiment. “Winters wouldn’t go near him,” Mampre recalled. Feiler had tried to repair Winters’ teeth and ended up making them worse.

One day, Captain Feiler ran into the hospital and breathlessly explained that he had almost been captured. He had been driving a truck full of soldiers when he saw Germans in front of him. He jumped out of the cab and threw a captured German Luger pistol into the woods. When Captain Buck Ryan, who had lent Feiler the Luger, asked him why he had done that, Feiler explained, “Do you know what would have happened if the Germans would have caught a Jewish boy with a Luger?” An unimpressed Ryan asked, “What do you think I’m gonna do to you?”

Mampre survived on cold C-rations and rarely slept. He guarded his brother’s flight jacket. “If I was hit,” Mampre explained, “that jacket would have been off me so fast,” taken by others who prized the jacket. He noticed that, unlike the Americans, the wounded Germans hollered for relief. He discovered decades later that the German Army provided amphetamines to its soldiers.

When the Germans bombed or shelled the barracks, Mampre and his comrades fled to the basement. During one shelling, Mampre gave his blanket and a chocolate D-bar to a man in his underwear sitting next to him. When it got light out, Mampre realized the man was a German. “Hey!” he shouted upstairs, “There’s a kraut down here!” Mampre took back his blanket.

In another instance, Mampre joked with a 17-year-old English-speaking German prisoner about exchanging uniforms. Mampre would be sent back to the United States as a prisoner, he explained to the kid, and the German could return home by following the American Army into Germany. The young man thought about the offer, and then said, “Ah, the hell with you. I want to go the United States. You go to Germany.”

No matter how desperate the situation became, Mampre did not worry. “I never thought we were in trouble.” When he heard that General McAuliffe responded to a German surrender demand with one word: “Nuts!” Mampre simply called it “pretty interesting.”

Mampre knew the campaign had swung in the 101st’s favor on December 23 when the skies cleared. Mustang fighters strafed the Germans, and C-47s dropped supplies. “That was a welcome sight,” he said. “I have such a tremendous respect for those pilots.”

Mampre did his duty and survived the siege of Bastogne, but after Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s 4th Armored Division broke the siege the day after Christmas, he was sent to a hospital on January 9, 1945. He does not remember why.

Mampre rejoined the 101st in Berchtesgaden, Germany. On his way, he passed through Baden-Baden, where he saw thousands of German prisoners in an enclosed camp. Once with the division, he gave a 3rd Battalion medic a ride in a jeep that kept jumping out of gear and into neutral. Mampre lost control of the vehicle and bounced it off some huge rocks. The other medic cut his leg badly but refused to go to a hospital, so Mampre sewed him up with some German medical supplies.

When the 101st occupied the town of Berchtesgaden in southern Germany, which included Adolf Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest mountaintop retreat, Mampre was assigned to the division medical group and occupied the Berchtesgadener Hof, one of the nicest hotels in town, which was going to be converted to a visitors’ center for dignitaries. The division surgeon sent Mampre to find out what medical personnel were needed at the hotel. Mampre returned to report to the colonel that all was taken care of. The surgeon then asked Mampre if he had moved into the hotel as medic, and he said he had. That made him the house physician.

Life at Berchtesgaden was good. Every morning Mampre ate speckled trout for breakfast, which British Air Marshal Arthur Tedder, Eisenhower’s deputy commander, caught in the mountain streams. For drink, Mampre found a stash of 1,000 liquor bottles from all over the world, including a dozen bottles of pink champagne. He took what he wanted and turned the rest over to the hotel’s bar. “I don’t know who got the money for that stuff,” he said.

Mampre did well for himself. He ended up with Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop’s watch, which was later stolen. He almost came into another fortune when a friend gave him a civilian pillow. Mampre kept it on his desk chair until two MPs and a woman showed up at his office. The woman pointed at the pillow, and MPs opened it up. It was filled with jewels.

While Mampre had just gone to Paris on leave, Nazi Germany surrendered. It was May 9, 1945. “The streets were a mob scene,” he recalled. “I was happy as a lark.” He spent the day riding around Paris and mixing with the crowds.

When it came time to go home, Mampre took a train to Marseilles, in southern France. Once there, Colonel Sink offered to allow him to fly home or go home with the whole unit. Mampre chose the plane, but before he left he reminded Sink of his comment about staying with the outfit until he died. “Well, I’m alive and I’m going to go home, and I’ll be home and a civilian before you leave Marseilles—goodbye, Colonel.” Mampre stressed the last words with a salute. Sink’s eyes popped, but he didn’t say anything.

Mampre’s plane touched down in New York, and he took a train to Chicago, and then traveled to Fort Sheridan, Illinois, where he separated from the Army. Soon after he returned to Skokie, Illinois, he married Virginia on November 17, 1945—before the regiment made it home. Mampre and Virginia had three children, Virginia, Susan, and Elizabeth. The Mampres were married for 63 years until Virginia’s death in 2009.

Al Mampre attended the University of Southern California. Instead of staying with ministry studies, he dual-majored in psychology and sociology. “My attitude was: ‘Maybe I should work on the people side of it.’” He received his bachelor’s degree from Pepperdine University and was earning a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1950 when he was offered a research fellowship with International Harvester at the old McCormick Works on the outskirts of Chicago. He stayed with the company until 1978, working in management development and as a public relations manager. He also did pro bono work for college students, lecturing at different schools. “I loved teaching,” he said.

Mampre thought the 2001 HBO series Band of Brothers,based on the Stephen Ambrose book, was rather accurate, but he had a few problems with the scene pertaining to him. In Episode 4, “Replacements,” members of Easy Company, sitting on British tanks, pointed out that Lieutenant Brewer (played by Brandon Firla), standing in the middle of the road, looked like General George S. Patton right before he was shot in the neck.

In actuality, said Mampre, “He was nowhere near a highway, and there were no tanks.” He recalled that Brewer was tall and handsome. “He looked like Ted Danson.” The episode also portrayed the incident as happening outside Nuenen, not Eindhoven.

Mampre was impressed, however, with actor Shane Taylor’s portrayal of medic Eugene Roe. Throughout the series, Taylor squatted on his heels whenever he sat down, just like the real Roe.

Over the years, Mampre’s back pain from the paratrooper landing on him in Holland became worse. Today, at 94, Mampre appreciates people’s interest in World War II, but he does not consider himself or his comrades heroes. “People say, ‘I couldn’t do what you did,’” but he disagrees. “We were ordinary people.”

Mampre uses a paratrooper in Bastogne as an example. Mampre watched a man climb a wall to string some communications wire between division and one of the regiments. An artillery blast knocked him down, but he climbed back up and resumed his work. Another shell knocked him down, and again he climbed back up. A third shell knocked him down, and he climbed back up to finish the job.

“Was he a hero?” Mampre asked. “No. He was mission oriented.” To Mampre, that’s how the Americans won the war. “We didn’t wait for orders. We saw what needed to be done, and we did it.”