By Blaine Taylor

Leningrad was the sacred city of Soviet Communism. The port city on the Neva River, 400 miles northwest of Moscow, began life in 1703 as Petrograd, or St. Petersburg, after its founder, Czar Peter the Great. For two centuries (1712-1918) it was the capital of the Russian Empire—a place of stunning architectural beauty and historical significance, a city of czars and czarinas, of gold-domed cathedrals, breathtaking Baroque palaces, and rich political intrigue.

Petrograd was also the scene of a major history-changing event: the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that overthrew the old order and ushered in a radical new style of government and economy ruled by a group of some of the most evil, power-hungry cutthroats who ever wrapped themselves in the blood-red banner of Communism.

The chief architect of the revolution was the leader of the Bolshevik Party, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, who changed his name to Vladimir Lenin. With his followers murdering their way to power, Lenin surrounded himself with brutal henchmen, such as Josef Stalin, Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, and others.

Five days after Lenin’s death on January 26, 1924, Petrograd’s name was changed to “Leningrad” to honor the late Marxist leader.

Because of his fear and hatred of Communism, Nazi Germany’s leader (Führer) Adolf Hitler decided that, when he invaded the Soviet Union, one of his first orders of business would be to wipe Leningrad off the face of the Earth. And Hitler was confident he would do just that.

After all, the Soviet Red Army had suffered a humiliating defeat (not to mention a million casualties) when it invaded its northwestern neighbor Finland in December 1939. This defeat, along with the fact that Stalin had gutted his officer corps in the 1930s, led Hitler to believe that the Soviets would be unable to stand up to his own invasion force of three million men.

In addition to the symbolism of the city’s name, by 1939 Leningrad was also an important Soviet industrial center, responsible for 11 percent of the USSR’s industrial production. Thus, Leningrad became German Army Group North’s major objective from the start of the massive surprise Nazi sneak attack on June 22, 1941. In fact, Leningrad’s fall was the key to all of Nazidom’s vast, projected Northern Theater of Operations’ goals during August 1941-January 1944.

Poised to attack was Germany’s Army Group North. On June 22, the German onslaught—codenamed Operation Barbarossa (after the red-bearded Frederick I, the king of Germany and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire)—would begin. Leningrad was AG North’s assigned objective.

The man Hitler had handpicked to take the former czarist capital was one of his most illustrious warlords, the 65-year-old, slim, bald, ascetic-looking Bavarian Army Field Marshal Wilhelm Josef Franz Ritter (Knight) von Leeb.

Leeb joined the Imperial Army in 1895. During World War I, he was awarded the Austrian Order of Max Josef that brought with it the automatic ennobling title of “von,” making him Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb. He rose quickly through the ranks, even during the interwar period.

In 1940, during Hitler’s invasion of France, it had been Leeb’s men who had pierced the vaunted Maginot Line. For this, Hitler personally handed him a jewel-encrusted Army field marshal’s baton on July 19, 1940, plus the prized Ritterkreuz (Knight’s Cross) of the Iron Cross.

Under Leeb’s command this June day were two armies (the 16th, with eight divisions, and the 18th, with seven) and one panzer group (the 4th, with eight divisions). Additional divisions were held in reserve. Leeb’s orders were to advance from East Prussia through Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, destroy Soviet forces in the Baltic area as it went, and capture Leningrad from the south.

The city’s leaders felt that Leningrad was about as prepared as it could be. Encompassed in the overall defensive area was the mega-command of the Leningrad Fortified Region, the municipal garrison, the Baltic Fleet, the Koporye, Southern, and Slutsk-Kolpino Groups, and the Mga Position as well.

In addition, the 23rd Red Army was stationed in the north between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, the 48th Red Army was deployed in the west, the 67th Army in the eastern sector, and the 55th in the southern sector, the Volkhov “Front” being commanded by Lt. Gen. Kyril Meretskov, recently released from an NKVD (secret police) prison. (A “Front” is the Russian equivalent of a U.S. Army Group.)

On June 27, 1941, just days after Barbarossa began, first-response civilian groups were established within Leningrad, with over one million people building fortifications on the city’s northern and southern perimeters that they fervently hoped would halt the Germans.

Red Army Col. Gen. Georgi K. Zhukov recalled 30 years after the war, “Leningrad is a large industrial center and seaport…. Before the war, Leningrad had a population of 3,103,000—3,385,000 counting the suburbs…. Had Leningrad fallen, the Red Army would have had to establish a new Northern Front to protect Moscow, and it would have meant the loss of our strong Baltic Fleet. Ten volunteer divisions were formed in Leningrad during June-August 1941, as well as 16 separate artillery and volunteer machine-gun battalions.”

The Southern Luga River Line of June 1941 connected that waterway with the Chudovo-Gatchina-Uritsk-Pulkovo posts, extending to the Neva River. Another linked the Peterhof-Gatchina-Koltuszk positions. The Northern Defense Line existed pre-1941 against the Finns in the Karelian Fortified Region.

Statistically, 190 miles of wooden barricades made from sawn timber joined 395 miles of barbed wire, 430 miles of antitank ditches, more than 5,000 mud and timber emplacements, weapons bunkers built of reinforced concrete, and 25,000 miles of entrenchments, all either built or dug by civilians. But could it hold against the mighty, seemingly unstoppable Germans?

Assisting Army Group North in this endeavor were the Finns. After the Winter War of 1939-1940 between Finland and the USSR (in which the Red Army was thoroughly embarassed by itsr small neighbor) ended with an armistice, Hitler made a pact with Finland; if the small, Nordic nation would join with the German Army in his invasion of the Soviet Union, he would provide the Finnish Army with modern weapons to defend against any future Soviet attacks. Finland, caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place, made a bargain with the devil.

Another figure the Führer expected to be present in fallen Leningrad was the legendary commander in chief of the hardy Finnish Army, Field Marshal Carl Baron Gustav Emil Mannerheim, whom he venerated.

On June 22—under the austere baron’s patriotic leadership—Finland joined the march on Leningrad. From June to September 1941, the Finnish Army actually outnumbered the Germans in the Northern Theater by 530,000 to 220,000, fielding 475,000 combat-effective troops—more than it had during the Winter War. The Finnish force included a strong artillery segment but only a sole tank battalion and little motorization for its infantry in contrast to the highly armored and motorized German forces.

Leeb’s next martial goal was to link up with the combat forces of the Finnish Army on the Svir River east of Leningrad. The German high command’s earnest expectation was that their Finnish allies would march around Lake Ladoga to effect juncture with the Nazis, but that was never to be.

There lurked a hidden trait in Mannerheim’s character—one that would prove fatal to the grim desires of Hitler and Leeb. Mannerheim, who had fought in the Russian Army during the 1905 war against Japan, remained to the end loyal to the Russian people and their culture, no matter how much and how often he might war against their Red leaders and politics.

Hitler’s campaign Directive #21 sought to delineate Finland’s projected role in Operation Barbarossa thus: “The mass of the Finnish Army will have the task—in accordance with the advance made by the Northern wing of the German armies—of tying up maximum Russian strength by attacking to the West, or, on both sides of Lake Ladoga.”

But Mannerheim would have nothing to do with razing Mother Russia’s holy city, much less with exterminating its population via Nazi starvation plans. Finnish President Risto Ryti agreed with the baron that Finland would not attack the city directly, no matter what the Germans demanded or offered.

From the very outset of their tenuous alliance, Mannerheim refused Hitler’s offer of command of an 80,000-man German corps. He also would not cooperate fully in the encirclement of the city. Thus, he stopped Hitler cold in his tracks, a hindrance that Leeb could never get around.

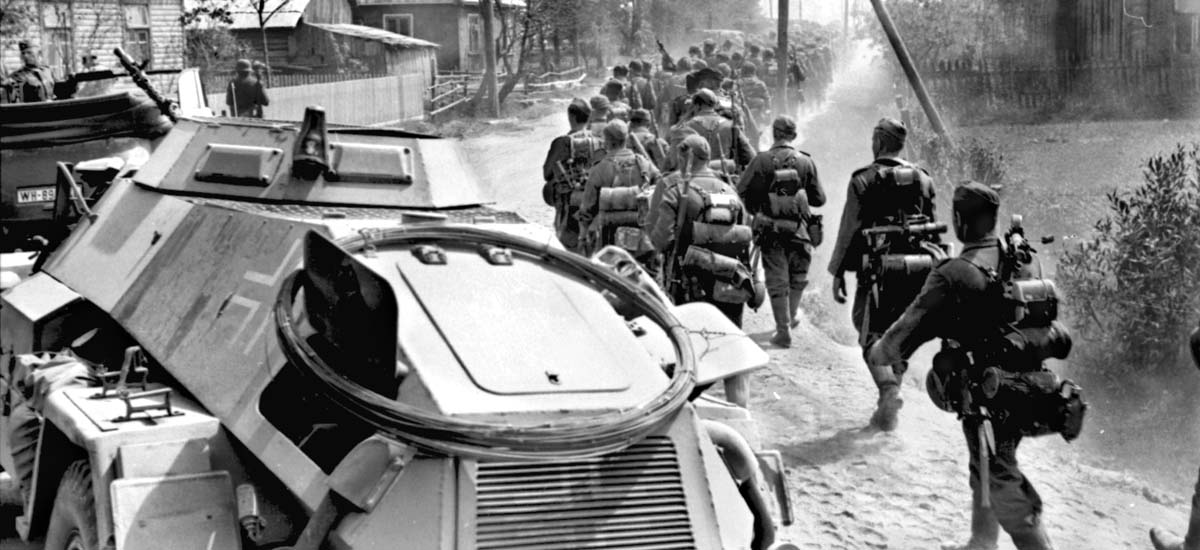

Early on June 22, the signal to begin Barbarossa was given. Leeb had designated as his spearhead the 4th Panzer Corps, led by 55-year-old Col. Gen. Erich Hoepner, a veteran of the Great War. In a message to his troops at the start of the operation, Hoepner said, “The war with Russia is a vital part of the German people’s fight for existence. It is the old fight of German against Slav, the defense of German culture against the Muscovite-Asiatic flood, and the repulse of Jewish Bolshevism. This war must have as its goal the destruction of today’s Russia—and for this reason it must be conducted with unheard-of harshness…. There is to be no mercy….”

Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group consisted of two panzer corps—the XXXXI, commanded by General Georg-Hans Reinhardt, who had breached Warsaw’s defenses in 1939, and the LVI, under the famed cavalryman, General Erich von Manstein, whose panzers had burst out of the Ardennes to overrun Belgium and northern France in 1940. Few other armored forces had commanders who were more capable than Reinhardt and Manstein.

At dawn, Hoepner’s group slammed into the 8th Red Army guarding the border, sending the Russians reeling. At first, the operation went spectacularly well. Soviet units that stood in Leeb’s way were pushed aside, overrun, turned into a bloody mash. Army Group North continued rolling, overcoming whatever obstacles the Soviets were foolish enough to place in their way.

Trailing in AG North’s wake were the murderous killing squads of the dreaded SS Einsatzgruppen (Special Purpose Groups), whose mission was to rid whole villages of their Jewish inhabitants. Leeb’s men also committed war crimes of their own against the rival populations.

In Moscow, Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov announced over the state-run radio, “Today at 4 am, without any declaration of war, German troops attacked our country … and bombed Zhitomir, Kiev, Sevastopol, Kaunas, and others from the air. The government calls upon you, citizens of the Soviet Union, to rally still more closely around our glorious Bolshevist party, around our Soviet government, around our great leader and comrade Stalin. Ours is a righteous cause. The enemy will be defeated. Victory will be ours.”

On its bloody way to Leningrad, the 4th Panzer Group won the Battle of Raseiniai (June 23-27) in Lithuania against Soviet armor, inflicting a reported 90,000 casualties on the Red Army. Before reaching the breached defensive Stalin Line, Hoepner had allegedly destroyed a thousand Soviet tanks.

As it powered its way forward, the 4th Panzer Group came to a major natural barrier, the Dvina River, which flowed into the Gulf of Riga. German engineers overcame this obstacle by quickly installing bridges across the water.

The Soviet 3rd Mechanized Corps was moved up to try and stop Manstein’s drive, but it was futile; the 3rd ended up losing 70 tanks, and survivors were sent fleeing from the battlefield.

The two panzer corps continued roaring toward Leningrad at breakneck speed, and the excitement of being part of such a momentous event buoyed the spirits of every German soldier. On June 24, General Christian Hansen’s X Corps took Kaunas and fought off counterattacks by the 23rd Rifle Division.

Meanwhile, the 18th Army, headed by General Georg von Küchler, was advancing along the coast while the 16th Army, under General Ernst Busch, was heading for the Memet River and driving a wedge between the Soviet 8th and 11th Armies. Luftwaffe planes were bombing enemy formations.

Everywhere the news was bad for the Red Army. On the 25th, the 21st Mechanized Corps attempted to block LVI Panzer Corps west of the Dvina River but failed. The 12th Mechanized Corps sent KV-1 and T-34 tanks against XXXXI Corps at Rasainiai, but these attacks, too, failed to halt the German drive, and the 12th Mechanized Corps was destroyed.

While the 16th Army was mopping up behind the 4th Panzer Group, Semyon Timoshenko, chairman of Stavka, the Soviet Armed Forces Supreme Command, ordered all available forces to the Dvina River in an attempt to seal off the XXXXI and LVI Corps bridgehead. Farther to the north, Küchler’s 18th Army was hit by strong counterattacks.

A hundred miles southeast of Riga, Latvia, on June 28, German troops entered Daugavpils and began clearing out the city’s Jewish ghetto, assisted by a segment of the population; more than 1,000 Jews would die during the first week of the German occupation.

On the same day, the Soviet Air Force unsuccessfully attacked the German bridgehead over the Dvina, and much of Leeb’s army group continued to pour through. It seemed as though the German juggernaut was unstoppable.

On July 1, the city of Riga, Latvia, fell to General Albert Wodrig’s German XXVI Corps, while farther to the north Finnish Army units made good progress against their Russian foes. Three days later, Manstein’s LVI Panzer Corps was at the Latvian-Russian border, while Reinhardt’s men had taken Ostrov. When the Soviets brought up tanks to halt Reinhardt, the Germans responded by destroying 140 of them with heavy artillery.

Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, was ecstatic when he got the news. “No one now doubts that we shall be victorious in Russia,” he said. “Of Bolshevism, nothing will be allowed to remain.”

As so it went, with one city, town, and village after another captured, and one Red Army counterattack after another thrown back with devastating losses. By July 6, German forces had occupied all of Lithuania and Latvia and were moving against Estonia.

The German high command, on July 8, sent a new order to Leeb. AG North was now to move XXXXI Panzer Corps to the Luga River before mounting an assault on Leningrad while LVI Panzer Corp was to make an attack toward Lake Il’men, more than 140 miles south-southeast of the city. On the 10th, Manstein’s corps captured the town of Porkhov, but Reinhardt’s XXXXI Corps had failed to take its objective at the Luga. It was the first time the German thrust had been blunted since Barbarossa began, and suddenly the Germans began to get worried.

The Soviet 8th Army brought Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group nearly to a halt, so Hoepner formed a kampfgruppe (battle group) from the 6th Panzer Division in XXXXI Corps and sent it north, hoping to find a way around the resistance. What it found, instead, were poor roads, soft sand, swamps, swarms of mosquitoes, numerous streams and rivers, and old wooden bridges that collapsed under the weight of the tanks and had to be repaired before the column could continue.

Whenever a tank or half-track got stuck in the mud or deep sand, the whole column halted and waited for recovery vehicles to come to the front to haul out the immobilized vehicle. The going was slow and exhausting, and after several days on the march, the battle group had gone only a few miles; at this rate, they would never get to Leningrad before winter.

As the column pushed ahead, the troops saw plumes of black smoke on the horizon; the Soviets were burning farms and villages so that the Germans would find nothing of value.

As if that weren’t bad enough, the clouds of dust raised by the tracks and wheels and boots of the kampfgruppe were a red flag to Soviet airmen who, thus alerted to their presence, swooped down with bullets and bombs flying.

In mid-July, food rationing was instituted in Leningrad, and prices skyrocketed as supplies dwindled. The priceless paintings in the Hermitage were crated up and trucked out of the city or hidden in deep cellars. Plans to evacuate 400,000 women and children were drawn up. German reconnaissance flights over the city increased, but there was no bombing—yet. Sandbags and protective scaffolding started to go up around monuments and public buildings.

On July 19, Hitler issued Directive #33 to all his invading forces, giving them specific orders as to what they must accomplish. To AG North, he said, “The advance on Leningrad will be resumed only when 18th Army has made contact with 4th Panzer Group and the extensive flank in the east is adequately protected by 16th Army.

“At the same time, Army Group North must endeavor to prevent Russian forces still in action in Estonia from withdrawing to Leningrad.” The directive also noted that Leeb’s army group was to advance to Lake Ladoga, north of Leningrad.

In Lithuania, meanwhile, the local militia, with German encouragement, murdered some 3,800 Jews. German soldiers—whether in the Einsatzgruppen or not—were also encouraged to engage in “ethnic cleansing” as they moved forward, wiping out Jews, Soviet commissars, prominent businessmen, and the Russian intelligensia.

At the end of July, an angry Hitler flew to his commander’s field headquarters, demanding that Leningrad must fall by December 1941, before the Russian winter set in. Leeb brought in more men, tanks, artillery, and aircraft for his next attempt. Surely now the city must fall.

On July 31, the Finnish Southeastern Army continued advancing toward Leningrad, giving the Soviet 23rd Army a bloody nose. The Finns also enjoyed having air superiority. On that day, Hansen’s X Corps reached the southern shore of huge Lake Ladoga. The German advance had come at a tremendous cost; at the end of July, the total of all German casualties since Barbarossa began stood at 213,000 men.

The Finns deployed north of Leningrad with the Germans holding down the southern approaches. It was the Finnish Army that severed the last Russian railway connection north of the city and at several spots in Lapland.

German Army elite Alpenkorps troops moved down from German-occupied Norway but obeyed the baron’s dictum that no attacks were to be made by German soldiers operating on Finnish soil. By August 31, his soldiers were a mere 20 kilometers from the city’s northern suburbs, at the 1939 Finnish-Russian frontier posts to Leningrad’s north, advancing also via Eastern Karelia.

After having taken Red Army salients at both Beloostrov and Kirjasalo on the Karelian Isthmus, the Finns deployed along the length of the former frontier on the shores of Lake Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland.

On August 6, Hitler announced his triad of main Russian campaign goals: “Leningrad first, Donetz Basin second, Moscow third.” Hitler was certain that he would take Leningrad within six weeks, and then Moscow. In eight weeks, Stalin would sue for peace and the Eastern Front war would be over by Christmas 1941.

Then the excitable Führer suddenly appeared to change his mind regarding the taking of Moscow, according to his own chief of the German general staff during 1938-1942, Col. Gen. Franz Halder: “When Army Group Central had reached its first objective, Hitler wanted it reduced to a weak holding force, and the bulk of its troops diverted to the north, so as to hasten the capture of Leningrad.

“It was an absurd idea to think of wheeling around a million or so men—and countless vehicles—in almost trackless country, just as though they were a battalion on the parade ground! It was an idea that didn’t derive from Hitler’s military thinking, but from his political fanaticism that had set itself on the destruction of Leningrad!

“When Army Group North—without any reinforcement from the Center—had approached Leningrad so closely that it was ready to move forward to its capture, it was Hitler himself who’d intervened, and forbade the attack! Now, he was suddenly disposed to content himself with [just] surrounding the city!”

On August 21, Hitler’s Directive #34 ordered Leeb to continue to press his attack between Lake Il’men and the town of Narva to link up with Finnish forces in order to encircle Leningrad. He also insisted that only after Estonia had been cleared of all Soviet forces was the final advance on Leningrad to be attempted. He projected the “encirclement of Leningrad in conjunction with the Finns,” followed during the next week by the blockage of railway evacuation of the city’s civilian population through the use of Luftwaffe bombings as well as via artillery bombardment of other exit points. There would be no escape or mercy for the city’s inhabitants.

The bloodbath ran into August, with the Germans continuing to decimate Red Army formations sent against them while, at the same time, losing more men than they could afford.

By August 16, Hoepner and his 4th Panzer Group had reached Soviet Novgorod, blitzing down the road to Leningrad’s Luga River Line. This established the Germans’ initial, future siege locations extending from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, the ultimate goal being to encircle the city.

Like his superior Leeb, Hoepner also practiced a scorched-earth advance against the hated Bolsheviks, fully implementing Hitler’s illegal and criminal shoot-on-sight “Kommissar Order.” Hoepner cooperated well with the murderous SS Einsatzgruppen in the killing of Jews, too.

Hoepner was the very man whom Adolf Hitler expected to lead his victory parade down the boulevards of subjugated Leningrad, making his boss, Field Marshal von Leeb, its celebrated conqueror as well.

Finland’s Marshal Mannerheim, with no desire to attack Leningrad, shocked the Germans by declaring on August 27 that his Finns would no longer act in direct cooperation with Leeb’s AG North; he was only interested in reclaiming for Finland the territory lost to the Soviets in 1940. Two days later, after realizing the Finns would not be helping him capture Leningrad, Leeb reorganized his AG North and prepared for a siege of the city without their aid.

On August 30, Army Group North’s advance into the Soviet Union reached Leningrad’s suburbs and severed Russia’s last railway connection at the Neva River. Now the encircled city was in a near vise-like death grip on both land and water. A German victory was at hand.

Finally, on September 1, German units came within artillery range of Leningrad, and the Krupp guns fired on the city for the first time. A few days later, Hitler, looking at the mounting casualty lists, decided that sending his troops into the city would be too costly and demanded that, instead, the city be starved into submission.

Also on that day, Mannerheim’s IV Corps defeated everything the Soviet 23rd Army troops could throw at him in the Battle of Porlampi. On the 7th, the victorious baron established his new, occupied Eastern Karelian Svir River field headquarters, and there he remained for most of the rest of the war. The Finnish Army had become, therefore, Germany’s ally in place only.

On September 8, Leeb’s forces took the Red Army position with the Germanic name of Mga-Schlissel’burg 10 miles to the east, cutting the last of its overland roadway communication lines.

That evening, the first major air attack on Leningrad was made with two waves of bombers hitting the city. They were aim-ing for the city’s food warehouses. One resident, Elena Skrjabina, watched the buildings go up in flames. “The Badaev warehouses are completely destroyed,” she wrote. “All the supplies of the city were concentrated there…. The destruction of the storehouse threatens Leningrad with inevitable starvation.”

The city was, in effect, almost totally blockaded. Thereafter would come the historic, protracted siege of 872 days and nights.

For the Soviet supreme command— Stavka—it was imperative that Lenin’s city not fall under any circumstances. The Soviet 54th Army tried to relieve the pressure on the city, and intense fighting took place at Sinyavino, about 10 miles east of Leningrad on the southwestern shore of Lake Ladoga.

Heavy fighting for the southern suburbs of Krasnoye Selo and Pushkin, the location of the Catherine Summer Palace where the priceless Amber Room was installed, also broke out. The palace was badly damaged in the fighting, and the panels that made up the Amber Room were removed and hauled back to Königsburg in East Prussia.

With the Finns declining to participate in the attack on Leningrad, Maj. Gen. Augustin Grandes’ 250th “Blue” Division, made up of Spanish volunteers, arrived and was thrown into battle against the Red Army in the sector between Lake Il’men and the west bank of the Volkhov. Elements of the XXXIV Panzer and XXXVIII Corps were added to bolster the Blue Division’s attacks.

On September 17, the Leningrad fighting reached its peak with six AG North divisions advancing from the south. To stop them, “The guns of the Baltic Fleet rained down shells,” Zhukov recalled, joined by both Soviet naval and air force squadrons. “Much depended on the Navy and its coastal artillery, that became more and more relevant as the battlefield moved closer to the seashore.”

Also participating in the shelling of the Germans were the guns of the historic 1917 Russian Revolution cruiser Aurora. Her big guns had been removed, transported inland, and repositioned south on the city’s Pulkovo Heights.

The Soviet Navy helped to supervise the city’s massive civilian evacuation efforts, the fleet commanded by Admiral Vladimir Tributs with Admiral Ivan S. Isikov activating six separate Marine and sailor brigades. Despite heavy losses, they attacked again and again, their commander himself being slain, and the Germans repulsing them repeatedly.

On October 16 came an ominous harbinger of winter—snowflakes. As the snowfall became heavier and the termperatures dropped, the German soldiers at the front realized that they had only their summer uniforms. No plans had been made to properly equip them because Hitler and the high command had made the catastrophic miscalculation that the war would be won before winter.

The Russians knew that they’d won the battle when field reports arrived stating that Leeb’s forces were “building dugouts, fitting out bunkers and pillboxes…and laying mines and other obstacles to protect their battlefields,” Zhukov remembered. “The enemy was preparing for winter, and prisoners confirmed this.”

Now returning to the fore was an issue that Hitler had earlier foolishly pushed into the background, winter clothing for his overextended armies in Russia. Recalled Col. Gen. Halder in 1949, “When the Army Commander-in-Chief [Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch] asked for immediate preparations to be made for the provision of specialized winter clothing, he received a curt refusal, with the remark that, by the beginning of winter, the fighting would have long since been over.

“For the German troops who’d still have to remain in the East as an occupying force, the Army’s normal winter equipment would suffice and that, of course, would be available.” It wasn’t, and the men froze, many to death.

The Soviets attempted to break the encirclement of Leningrad on October 20, when they prepared to launch the “Second Sinyavino Offensive”—63,000 troops, 97 tanks, and 474 artillery pieces against the Germans’ 54,000 soldiers.

As temperatures dropped, the battle around Leningrad continued to heat up. In Moscow, Marshal Zhukov studied the casualty figures for the front and was shocked to see that these troops, which had numbered a million men on October 1, were now down to 250,000. To the south, the Soviet leadership noted with alarm that the Germans were now just 30 miles north of Moscow.

To the west, in German-occupied Lithuania, the commander of Einsatzkommando 3 reported, “I can confirm today that Einsatzkommando 3 has achieved the goal of solving the Jewish problem in Lithuania. There are no more Jews in Lithuania.” He was overstating the situation, but the message was clear. Wherever the German troops advanced, they left thousands of dead Jews in their wake.

Winter now came on with a vengeance. The Germans’ motorized vehicles stopped running, guns froze, draft horses went to sleep and never awoke. Neither did many men. The Soviets, better equipped with proper winter gear, thanked their faithful comrade, General Winter. He had stopped Napoleon over a century earlier; perhaps he would do the same now.

Corporal Wilhelm Lubbeck, an artillery forward observer in the 58th Division, recalled, “We began to confront bitterly freezing temperatures of minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. This was far colder than any conditions we had ever experienced in Germany. In the harsh months that followed, the wounded on both sides sometimes froze to death where they fell before they could be transported back behind the lines for medical care.

“The temperatures dropped so low that it actually caused the grease in our weapons to freeze unless we fired them regularly or took measures to protect them from the cold. Other soldiers told me that they witnessed entire steam engines that had been frozen solid down to the grease in their wheels.”

On November 27, Hitler dangled a carrot in front of Finnish Foreign Minister Rolf Witting. He promised that Leningrad would, indeed, be razed and then handed over to Finland, with the new, postwar Finnish-German frontier demarcation line being the Neva River. Despite the offer of this gift, the Finns would stay put into summer 1944.

Leeb now found himself in a martial quandary, as his own forces could not attack the Red stronghold from the north.

Still, the restored current Finnish frontier was but a mere 22 miles northeast of downtown Leningrad, with the threat of a possible future attack from the Finns being a military factor that any defending Soviet commander from then on had to take into account.

Commanding both the 7th Red Army and Leningrad’s Volkhov Front during the siege was Kyril Meretskov. He was named commander of the Leningrad Military District and assigned to the Leningrad Front to command the 4th Red Army at the Battle of Tikhvin. After prolonged heavy fighting in deep snow at Tikhvin, 110 miles east of Leningrad, the Red Army finally defeated Georg von Küchler’s 18th Army on December 9, throwing the frozen survivors back westward to the Volkhov River. Meretskov’s victory at Tikhvin was hailed as the first large-scale, successful Soviet counterattack of World War II.

On December 20, in response to requests by his field commanders to pull their men back when success was hopeless, Hitler issued his “no retreat” order: “The will to hold out,” he told Franz Halder, “must be brought home to every unit. The troops are to be forced to put up fanatical resistance in their lines, regardless of any enemy breakthrough on their flanks or rear. Only this kind of fighting will win the time we need to move up the reinforcements I have ordered from the home country and the west.”

Starvation was beginning to grip the citizens of Leningrad. The average daily death toll was 1,500, but on Christmas Day 1941 3,700 people starved to death. With the supply of bread completely inadequate to keep the population alive, people ate anything they could find. Some gnawed wood, dug up and ate tulip bulbs, or downed wallpaper paste. Dogs and cats disappeared. Soon cannibalism would become commonplace.

A woman recalled with horror seeing the partially eaten body of a young girl half hidden under an apartment stairwell. A city official admitted that Leningrad was a city “overrun with cannibals.”

Resident Alexander Boldyrev wrote in early January, “The death rate is astronomical…. I saw with my own eyes a caravan of sledges, loaded with coffins, boxes, or simply corpses in sacks, making its way to the cemetery. There I saw corpses left just as they were, dumped at the entrance, turning black in the snow…. Are we nearing the end? We are a city of the dead, shrouded in snow.”

Adding to the citizenry’s misery was the fact that the city’s central heating system was shut down due to a lack of fuel.

With all roads and railroads in and out of the city cut off by the siege, there was only one way to bring vital supplies into it and take starving civilians out—the “Road of Life.” Lake Ladoga, the huge body of water north of Leningrad, freezes solidly in the winter, so a plan was devised to bring long convoys of trucks full of foodstuffs over the ice.

The Luftwaffe tried bombing and strafing the convoys—sometimes seven or eight air raids a day—and was to some degree successful. Yet, despite the danger, the trucks continued to run night and day. And people in the city continued to die; in February 1942 an assessment reported that at least 8,000 died every day.

On January 8, 1942, a week into the new year, Meretskov’s Volkhov Front opened the Demyansk Offensive (sometimes called the Lyuban Offensive) with the 2nd Shock and 59th Armies in their white camouflage smocks violently attacking the German I and XXXVIII Corps but without accomplishing much. The Northwestern Front, on the other hand, attacked the SS Totenkopf, 30th, and 299th Infantry Divisions south of Lake Il’men, inflicting heavy casualties. Combat around Leningrad continued to be savage. Never before or since had such huge numbers of soldiers fought with such ferocity.

Throughout the month, the Soviets battered away at their enemy, making only slight dents. For the next few weeks, the exhausted Red Army paused, using that time to gather reinforcements, replenish its stocks of ammunition and artillery shells, and plan for a new offensive.

In the Demyansk Pocket, 90,000 German soldiers representing five divisions were trapped; only air drops of food and ammunition enabled them to keep fighting. In March, relief columns would try to break through the Soviet encirclement to free their comrades.

For the soldiers in the pocket, life was terrible. Personal hygiene was almost impossible; baths and showers were a dim memory, and shaving was done every couple of weeks, if at all. Lice invaded every seam of every piece of uniform. Dysentery and frostbite were rampant.

March 19 saw Küchler’s 18th Army attack the 2nd Shock Army on the Volkhov River and inflict heavy casualties while surrounding 130,000 Red Army soldiers. A five-division relief force then prepared to come to the rescue of their comrades who had been trapped in the Demyansk Pocket.

Wilhelm Lubbeck, 58th Division, recalled his days fighting at the Volkhov: “When the spring thaw arrived in early April, it swiftly turned the Volkhov battlefield into a muddy bog. The warmer weather was initially welcomed, but we would soon discover that conducting combat operations in the steamy heat of a swamp was even worse.”

One day, Red Army troops charged Lubbeck’s position that he was sharing with a machine gunner. Firing furiously, the MG-42 gunner frequently had to change barrels, tossing the red-hot ones into a puddle of water to cool them. Lubbeck had an MP-40 machine pistol, and he, too, was going through ammunition at a fast rate. As he bent down to load another magazine, he noticed that the machine gun beside him had gone silent, so he “assumed that the gunner was also reloading or again switching the barrel of his weapon.

“A glance to my right revealed the gunner crumpled on the ground beside me. A second later I spotted blood running from a hole in his temple just under the rim of his helmet. The shot that killed him had not been audible in the din of combat, but its precision made it instantly obvious to me that it came from a sniper’s rifle.”

He chillingly realized that, had he not bent down to reload his weapon when he did, the bullet might have been meant for him.

In April 1942, Hitler issued another directive, this one ordering AG North to once again capture Leningrad and link up with the Finns.

On April 20, perhaps as a birthday present to their Führer, the German relief force finally cracked through the Soviet ring around the Demyansk Pocket and linked up with the SS Totenkopf Division on the Lovat River.

Ten days later, the Soviets called off their disastrous Demyansk/Lyuban Offensive, which had cost them more than 95,000 men killed and missing and more than 213,000 wounded. On May 30, a German counterattack encircled and destroyed the 2nd Shock Army in a series of attacks lasting until June 25. Meanwhile, in Leningrad as many as 100,000 people a month were now dying of starvation.

Fighting in the north reached a stalemate over the summer with both sides too exhausted to defeat the other, while Germany’s Army Group Centerl and Army Group South continued to battle as desperately as ever.

In Leningrad on August 9, 1942, a special concert was held at the Philharmonic Hall. The orchestra was to perform Dmitry Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, which the composer, who had remained in the city throughout its siege, had written for the occasion. It would also be broadcast over the radio.

The hall was packed with people—gaunt, starving people and wounded soldiers who needed something uplifting for their souls. The conductor, Karl Eliasberg, announced, “Comrades, a great event in the cultural history of our city is about the take place. In a few minutes, you will hear for the first time from our fellow citizen, Dmitry Shostakovich. He began his great composition here in Leningrad, when the enemy—insane with hatred—first tried to break into our city. When the fascist swine were bombing and shelling us, everyone believed that the days of Leningrad were over. But this performance is proof of our spirit, courage, and readiness to resist!”

When the concert was concluded, many left the hall with tears in their eyes—but a new spirit in their hearts. They would need it, for the siege of their beautiful city would go on for many more months. The Sinyavino Offensive was launched on August 27 in another attempt to break the encirclement; like the others, it too failed.

On January 12, 1943, the resurgent Red Army struck again with 12 divisions, reestablishing at last the resupply road to the besieged metropolis that still remained under continuous German bombardment.

Two days later, the Soviets made one of the most important technological finds of the war, between two Red Army frontline posts, with Zhukov himself present. “Our gunners had hit a panzer that looked different from the types of tanks we knew,” he said. “The Nazis … were trying very hard to drag it away…. We had a special group formed of an infantry platoon and four tanks to capture the enemy tank, and tow it to our positions … supported by a powerful gun and mortar shelling.

“It was the first experimental specimen of a new, heavy panzer called Tiger, that the Nazi command was testing on the Volkhov Front…. [Our] experiments revealed its most vulnerable points …. at once circulated among all Soviet troops. That is why our tank men and gunners didn’t falter when the Germans first used the Tigers en masse in the Stalingrad and Kursk battles later.”

Another attempt to break the siege was made on that same day—January 12, 1943—called Operation Iskra (Spark). This was more successful, and a land corridor was forced open, allowing supplies to be brought in and civilians to be evacuated.

It took another year—until January 27, 1944—before the Leningrad-Novgorod Strategic Offensive finally ended the Germans’ iron grip on the city. Some estimates say that as many as 1,500,000 citizens of Leningrad died of starvation, disease, and German bombardment during the 872 days of siege.

Boasted Marshal Zhukov proudly 30 years after the battle, “Leningraders, soldiers, and seamen preferred to die rather than surrender their city. Between July 1941 and the end of the year, the factories produced 713 tanks, 480 armored vehicles, 59 armored trains, and more than 3,000 regimental and antitank guns; nearly 10,000 mortars, over three million shells and mines, and more than 80,000 rocket projectiles and bombs. The munitions output increased 10 times over in the latter half of 1941, as compared with the first six months” of peace.

In all, 725,000 troops of Nazi Germany, Finland, Fascist Spain, Romania, Hungary, and Italy confronted 930,000 Reds. By siege’s end in 1944, the Axis had lost 579,985 men killed, wounded, and missing in action.

Soviet Northern Front losses comprised 1,017,881 killed, captured, or missing, or 3,436,066 including wounded and sick, with 400,000 more perishing during the evacuations.

Still, Marshal Zhukov had reason to remain jubilant in 1974: “For the first time in the history of modern wars, the besieger who’d blockaded a large city for a long time was routed by a simultaneous strike from outside and inside the beleaguered region.… The enemy had failed to dampen the fighting spirit of the city’s inhabitants or paralyze the work of its industries!”

When one visits the renamed St. Petersburg today, one finds the city completely rebuilt and restored to its prewar glory, with monuments and museums dedicated to the sacrifice and heroism of the city’s residents and defenders. But any traces of the terrible damage are long gone. It is once again beautiful.