By Eric Niderost

The high command of the Imperial Russian Army, known as Stavka, met on April 14, 1916, at Mogilev in Belarus to discuss possible offensive action against the Germans and their Austro-Hungarian allies on the Eastern Front. Stavka Chief of the General Staff General Mikhail Alekseyev was the main speaker at the gathering. Among the other high-ranking officials attending the meeting were General Dmitri Shuvaev, the Russian war minister; Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich, inspector general of the artillery; and Admiral A.I Ruskin, chief of the naval staff.

Nicholas II was also present, not only as czar and autocrat, but also as supreme commander of all Russian armed forces. Many privately thought his self-appointment to supreme command was an unmitigated disaster, coming as it did after a string of Russian defeats at the hands of the Germans. Nicholas had no military experience or training in war, and his martial exploits were confined to wearing elaborate uniforms and taking the salute in parades and reviews.

Nicholas presided at this meeting but said little and remained so passive he must have seemed a mere cipher. The most important people at the meeting were the three front commanders, because they were the ones who would be tasked with making Stavka’s orders a reality. General Aleksei Kuropatkin commanded the Northern Front, General Aleksei Evert commanded the Northwestern Front, and General Aleksei Brusilov commanded the Southwestern Front.

The atmosphere in the room was one of pessimism and gloom, although no one was willing to have Russia capitulate to Germany. Since the outbreak of war in 1914 Russia had willingly assumed the role of sacrificial lamb, slaughtered on the altar of Allied solidarity. In August 1914 Russia had attacked Germany prematurely before it had had an opportunity to fully mobilize when the French were hard pressed on the Western Front. Their Gallic allies had all but begged them to do so, and the Russians complied with a hasty invasion of East Prussia.

As a result, the Germans were forced to transfer troops to the East, a major factor when they were defeated at the Marne and their offensive ground to a halt. Russia had helped save France, but at a terrible cost. The Russians were utterly defeated at Tannenberg in August, and by some estimates sustained as many as 100,000 casualties.

Worse was to follow. The Germans launched the Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive in 1915, forcing the Russians into what later was termed the “Great Retreat.” Warsaw fell, and Russian Poland was occupied by German troops. As the weeks went on, and defeat piled upon defeat, it seemed nothing could slow the German juggernaut, save topography.

The troops of the Imperial Russian Army, bloodied and battered, were nevertheless optimistic as they trudged ever eastward. Many of them—even the illiterate peasant soldiers who filled the ranks—took comfort in the traditional Russian tactic of trading space for time. In 1812 Napoleon had been lured into the vast Russian hinterland, a movement that planted the seeds of his later destruction.

“The retreat will continue as far—and as long—as necessary,” Nicholas told the French ambassador. “The Russian people are unanimous in their will to conquer as they were in 1812.” A Russian joke said that the czar’s army would retreat to the Urals, on the boundary of Europe and Asia. By that time, distance and attrition would wear enemy armies down to one man each. The Austrian would surrender, according to custom, and the German would be killed.

Nevertheless, a sense of war weariness and futility began to seep into the Russian psyche. This was not 1812; indeed, it would take far more than the Russian winter to dispose of the Germans and their junior partners the Austrians. The Central Powers had inflicted two million casualties on the Russian armies, even though Russia was not yet knocked out of the war. “The Russian bear had escaped our clutches, bleeding no doubt from more than one wound, but still not stricken to death,” said German Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg.

The meeting at Mogilev was colored by the events of this recent past. The mood was somber, and there was probably a sense of déjà vu when General Alekseyev said that Russia had agreed to a spring offensive, largely to support a British drive on the Somme scheduled for the summer of 1916. It would be limited and involve the North and Northwestern Fronts.

Stavka envisioned a two-pronged attack along the Divna River, but Generals Evert and Kuropatkin, who would execute the proposal, vehemently objected. They pointed out that scarcely a month before an offensive in the vicinity of Lake Narotch had been a fiasco. No fewer than 300,000 Russians had been unable to get the better of 50,000 Germans, and the effort collapsed in a sea of mud, blood, and freezing temperatures. The Russians suffered upward of 100,000 casualties, including 10,000 who died from exposure.

Alekseyev brushed aside their objections. While conceding that Russian losses had been great, he observed that as many as 800,000 fresh troops would fill the depleted ranks. This gave the Russians more than enough troops to launch a new offensive. Evert and Kuropatkin were not convinced, but they grudgingly agreed to a limited attack.

General Aleksei Brusilov then spoke. The balding sexagenarian, with his intense eyes and a long, thin mustache, still looked like the dashing cavalryman he had once been. He had last seen active duty in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 where he had served with distinction. Four decades is a long time to have been absent from the battlefield, but he made up for it by an open, enquiring mind that displayed brilliance if not genius. Brusilov studied Western European military techniques and knew how to adapt them to a different climate, geography, and even culture.

“I propose that we should launch an offensive on the Southwestern Front to support the plan,” said Brusilov. “We have numerical superiority over the Central Powers; why not use it to our advantage, and attack on all fronts simultaneously? I ask only the express permission to attack on my front at the same time as my colleagues.”

After Brusilov finished there was a stunned silence. He was proposing an attack that would stretch for hundreds of miles, and the majority of the officers around the room had little confidence that the Imperial Russian Army could mount such a large-scale attack. Brusilov had another opinion. With meticulous preparation, enough armaments, and a change of tactics, he was sure the Russians could achieve a breakthrough and at the very least knock Austria-Hungary out of the war.

Brusilov knew that the terrible defeats Russia had suffered at the hands of the Germans were not the fault of the common Russian soldier. The Russian Army was composed mainly of conscripted peasants, whose immediate ancestors had been downtrodden serfs. They were stoic, stubbornly brave, and could endure hardships and wounds that might wear down or kill a Western soldier. Granted the peasants were illiterate, but they did not need to read and write to pull off a successful attack. For the millions of men who filled the ranks, a deep and abiding faith in Orthodox Christianity was all they needed. And after God, their faith was in the czar, who would lead them to victory against the Teutonic invaders.

Alekseyev tried to dissuade Brusilov, saying he could expect no artillery support and certainly no reinforcements. Brusilov said he accepted those conditions and still wanted to go ahead. Alekseyev, bowing to the inevitable, gave Brusilov’s plan his conditional approval.

After the meeting, General Nicolai Ivanov, the former commander of the Southwestern Front and at that time an adjutant to Czar Nicholas, made a last-ditch effort to stop the Brusilov by appealing directly to the czar. Nicholas, usually indecisive on such matters, refused to intervene. “I don’t think it is proper for me to alter the War Council’s decisions,” Nicholas said. “Take it up with Alekseyev.”

Russia had begun the war in 1914 ill equipped for a modern conflict. The country was still developing, with its industrial revolution in its adolescent phase, and modern war demands mass production. At that time, Russian factories were producing only 1,300 shells a day, which amounted to 35,000 a month, while Russian artillery was using 45,000 shells a day. The Russian Army outfitted its infantry with the 1891 model Mosin 7.62 mm rifle. It was an adequate weapon, but production lagged the first year. Some recruits literally were sent to the front without weapons under the assumption that they might be able to pick up a weapon from a dead or wounded comrade.

By early 1916 the situation had improved. Russian factories were producing 100,000 rifles a month. Additional arms were obtained from the Allies. Although there were still shortages, Brusilov was confident that precise planning could neutralize the problem. For one thing, artillery barrages just before an offensive tended to be very long. This enabled the enemy to know precisely where the blow would fall. With such knowledge, the enemy could shift reserves to the threatened spot.

Brusilov intended to order shorter barrages to baffle the enemy. Austrian commanders would be kept guessing as to what the brief bombardments really meant. On the one hand, it might mean that a major offensive was planned. On the other hand, it might simply be a diversion to distract from a major assault at some other point.

Offensive action in World War I was understandingly obsessed by the concept of puncturing an enemy’s line in order to bring about a breakthrough that would lead to victory. Conventionally, that meant a sledgehammer blow on one specific, narrow point on the enemy’s trench line, and then pouring in as many reserves as you could once that breakthrough was achieved.

Brusilov did not entirely abandon the narrow, overwhelming thrust concept, just modified and expanded it. There would be not one push, but four—one for each Russian army under his command. What is more, the attacks would be launched simultaneously. “I considered it absolutely vital to develop an attack at many different points,” said Brusilov.

Brusilov was nothing if not thorough. He was blessed with a meticulous attention to detail. Nothing seemed to escape his notice. Russian artillery units were assigned specific objectives that they were to achieve. Light guns would first blast holes in the prickly barbed wire entanglements that fronted Austrian positions. Brusilov required that there be at least two holes, both measuring about 14 feet.

With that task accomplished, the artillery would switch to neutralizing any Austrian guns in the enemy forward positions. The Russians knew exactly where Hapsburg gun emplacements were from a combination of prisoner interrogation and aerial reconnaissance.

Brusilov stipulated that attacks were to consist of at least four waves. The first wave would be armed with rifles and hand grenades. Its task was to take the Austrians’ first trench line and neutralize any Austrian guns that escaped Russian bombardment. The second wave would follow the first, advancing 200 paces behind. The second wave was entrusted with the most important assignment of all, which was the capture of the second line of Austrian trenches.

“We have to consider that our opponent normally places the strength of his defense in the second line, and therefore troops halting in the first line serve only to concentrate the enemy’s fire,” said Brusilov. Thus, it was of vital importance that the second line to taken as rapidly as possible. The second line was the backbone of the Austrian defense system. Once the second line was carried, Brusilov believed the remaining lines would fall more easily.

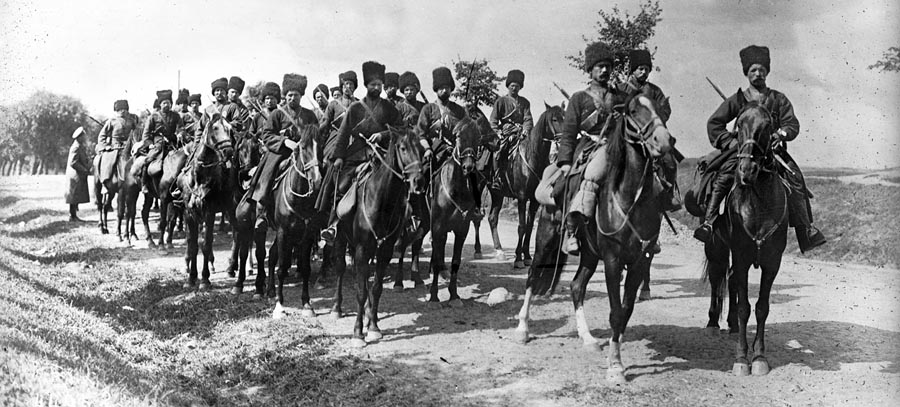

At that point, a Russian third wave would fan out and exploit the success. The troops would bring forward their machine guns to prevent any attempt by enemy forces to repair the breech in their lines. A fourth wave would consist of light cavalry, such as the dreaded Cossacks. These expert horsemen would ride deep into the enemy’s rear.

Brusilov issued a directive to his subordinate commanders on April 19, 1916, that detailed his concepts and methods and how they would be carried out. He planned to launch the offensive along the entire 250-mile length of the Russian Southwestern Front, which stretched from the Romanian border in the south to the Styr River in the north. It was an ambitious undertaking.

The attacking troops had two key objectives: Lutsk and Kovel, both important railroad junctions. In addition, his four army commanders would be free to choose which segment of the front they wished to attack. Brusilov stipulated that the segment chosen ideally would be from nine to 12 miles wide; however, it could be a minimum of six miles wide or a maximum of 18 miles wide.

There was another factor in Brusilov’s favor. It was something that could not be measured by lists of men and armaments. This was the sheer contempt the Germans and Austrians held for their Russian foes. Just two days before Brusilov launched his offensive, Colonel Paulus von Stoltzmann, General Alexander von Linsingen’s chief of staff, dismissed any notion of a Russian attack. “The Russians lacked sufficient numbers, relied on stupid tactics, and thus had absolutely no chance of success,” he said.

Austrian preoccupation with Italy and the Italian Front also played a role in Vienna’s complacency. General Conrad von Hotzendorff, chief of the Austrian general staff, considered Russia a broken reed, still capable of some fighting but no longer a viable threat. Instead, he focused his attention on the frontier between Northern Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire where the Italians and Austrians were locked in a bloody, high-altitude struggle in Alpine mountains and valleys.

Italy had been an ally of Austria, but when the war broke out the country declared its neutrality. After a series of complex negotiations Italy joined the Allies in 1915, hoping in the end to be rewarded with parts of the Tyrol and territory on the Dalmatian coast. This sudden about face enraged Hotzendorff and most other Austrians. To him, as to other Austrians, this was betrayal, and he was obsessed with punishing a country that in his eyes showed so much deceit.

This Italian obsession was to bear bitter fruit for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The combination of contempt for the Russians and desire for revenge against the Italians created an environment that was likely to bring Austria-Hungary to the brink of total collapse. Hotzendorff compounded the problem by transferring battle-tested units from the Eastern Front to the Tyrolean (Italian) Front and replacing them with battalions that were mediocre at best. What is more, he transferred nearly all of the Austrian heavy artillery, approximately 15 batteries, to the Tyrol.

The Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army was a reflection of the empire at large, a polyglot force in which as many as 15 languages were spoken. The lingua franca of the empire’s armed forces was German; otherwise, the average Hapsburg soldier spoke his native tongue. By 1916 the Austro-Hungarian officer corps had been reduced by 50 percent as a result of casualties incurred since the beginning of the war. Many of these were prewar officers who had taken it upon themselves to learn the language of their ethnic commands, yet by mid-war they were gone.

The Austrians were pleased, even complacent, about their defensive arrangements on the Eastern Front. They had constructed a formidable layered defense in the region around Lutsk that serves as a good example of what the Russians would be up against. The layered defense in this sector consisted of three lines of heavily fortified trenches. A 40-foot-wide belt of barbed wire fronted the Austrian position. The Austrian generals had placed the bulk of their infantry in the rear trenches where they were protected in huge concrete-reinforced dugouts. These steps were taken to ensure that the Russian artillery would not inflict serious casualties on the vulnerable infantry.

The Austrians positioned their field artillery behind the first line of trenches. The first trench line, which bordered the no-man’s land between the armies, was protected with earthen berms punctuated by concrete-reinforced positions for machine guns placed to deliver enfilade fire. The field artillery was situated behind the first line of trenches. The field artillery had to be within 3,000 yards of the first line of Russian trenches to be effective.

The Austrian troops lived a pleasant life at the front, with all the proverbial comforts of home nearby. The soldiers had at their disposal bakeries, sausage factories, and equipment for pickling and smoking meat. They even planted vegetable gardens and grew their own grain. To minimize the strain of hauling equipment, they used dogs to pull sleighs on which they put weapons and supplies.

Thus, the Austrian Eastern Front defenses were well planned and designed. “They were beautifully constructed of great timbers, concrete, and earth,” noted one observer. “In some places, steel rails had ben cemented into place as protection against shell fire.”

The Russian Southwestern Front comprised four armies: General Alexsei Kaledin’s Eighth Army, General Vladimir Sakharov’s Eleventh Army, General Dmitri Scherbatschev’s Seventh Army, and General Platon Letschitski’s Ninth Army.

The Central Powers had two major army groups on the Eastern Front: Army Group Linsingen and Army Group Bohm-Ermolli. Archduke Joseph Ferdinand’s Fourth Army, which technically was part of Group Linsingen, held the ground just south of the Pripet Marshes. In the coming offensive, the Russians would mount some of their heaviest attacks against this army.

Army Group Bohm-Ermilli consisted of two armies: the First and the Second. General Paul Puhallo von Brlog’s First Army held the position to the immediate right of the Fourth Army. By contrast, the Second Austro-Hungarian Army held the front between Dubno and a point north of the Tarnopol-Lemberg railway. The Central Powers front was rounded out by General Karl von Pfanzer-Baltin’s Seventh Army and General Karl von Bothmer’s South Army, the latter predictably the Central Powers’ anchor to the far south.

The great Brusilov Offensive began at 4 am on June 4, 1916. General Kaledin’s Russian Eighth Army on Brusilov’s right wing at Volhynia offers a good impression of the opening stages of the attack. The Eighth Army comprised the Eighth, Thirty-Ninth, and Fortieth Corps. The three corps fielded a combined strength of 100 battalions. The Eighth Army was deployed on a front about 30 miles long for its advance toward Lutsk, which was its main objective. Their opponents were Archduke Ferdinand’s Fourth Army.

Kaledin’s artillery opened up at the appointed time. No fewer than 420 heavy guns and howitzers pummeled the Austrian trench lines with uncanny accuracy. The rain of shells tore apart trenches and eviscerated Austrians unlucky enough to be in the vicinity, transforming a formerly quiet sector into a nightmarish scene. Other shells gouged out large craters, sending fine particles of sandy soil skyward in great clouds. After five hours, the guns fell silent.

At that point, the brown-uniformed Russian infantry began a steady advance forward. The Russian Eighth Army’s main thrust was led by the 102nd Reserve Infantry Division and the 2nd Rifle Division. The troops were eager to engage the enemy after weeks of practice and training.

When the dazed Austrian troops moved into the first trench following the shelling, and peered ahead into no-man’s land, they expected to see a typical attack unfold similar to those that had occurred throughout the first two years of the war. Long skeins of Russian infantry would advance from a distance, indistinct brown streaks on the horizon that would gradually morph into lines of Russian soldiers, bayonets fixed, advancing at the run. Thousands of Russians shouting “Urrah!” above the din of battle would be mowed down by Austrian machine guns. During their long and dangerous advance, the Russian infantry would be in range of the enemy machine guns the entire time.

But this time, as if by magic, the Russian soldiers were much closer. It was here that meticulous Russian planning started to produce results. Unseen by the Austrians in the previous weeks, the Russians had tunneled close to the enemy. The Russians poured out of vast, man-made caves that held as many as 1,000 men. Some of the tunnel entrances were as close as 50 paces from the Austrian first trench.

Worse still, the Austrians discovered that the fine-grained sandy soil that had been kicked up by the previous bombardment had clogged their machine guns, rending them inoperable. Much of the Austrian artillery was similarly clogged, and its crews desperately tried to limber the guns and escape before being engulfed by the Russian tide.

As they emerged from their underground bunkers, Russian soldiers were met by bearded Orthodox priests carrying icons and religious banners. The blessings bolstered the already deep religious faith the average Russian soldier had in God and the czar. The spirit of “Bozhe, Tsarya Kharani” (“God Save the Czar”) pervaded all ranks.

The Austrian Fourth Army headquarters was located at Stavok, a small town near the front lines. Seeing what was happening, the headquarters staff jumped in their vehicles and sped off to avoid capture. Abandoning his royal dignity, Archduke Joseph Ferdinand fled the sector when the Russians drew close to Lutsk.

In a curious throwback to another era, someone produced the Fourth Army regimental standard. This colorful flag was emblazoned with the black double-headed eagle of the Hapsburg dynasty. The individual waved it back and forth as a rallying point. Amazingly, it did rally a handful of Austrians, and they fought hand to hand until they were swept away by the Russian advance.

The Russians had overrun all three Austrian trench lines by nightfall. The demoralized Hapsburg defenders were in full retreat. In the first two trenches, three quarters of Hapsburg casualties had been from gun or artillery fire; in the third trench line, the defenders simply surrendered.

By June 6 the Austrians had been pushed behind the Styr River, and a few days later Lutsk, one of the main objectives of the Russian effort, had fallen to the czar’s troops. In the first two days the Russians had captured 77 guns and 50,000 men.

But Brusilov’s successes could only go so far. Indeed, his success was dependent on actions taken by his colleagues in the Northern and Northwestern Fronts. General Evert of the Northwestern Front, never an enthusiastic supporter of Brusilov’s plan, dragged his heels and refused to launch his own attack. The delay compromised the Russian offensive, but nothing seemed to get Evert to move more rapidly. He finally launched a tardy attack on June 18, an incredible two weeks after Brusilov’s opening moves.

It was almost as if Evert was working for the Central Powers, because the delays allowed the German high command to send reinforcements to the threatened areas. German Chief of Staff Erick von Falkenhayn talked his Austrian counterpart, Conrad von Hotzendorff, into transferring troops from the Italian Front to the Eastern Front. The Germans might have been caught napping, but the somnolent mood was quickly dispelled. Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who commanded the Eastern Front forces, used more efficient railways to speed German reinforcements to the threatened front.

The Germans on the Eastern Front were also proving much harder to overcome than their Austrian allies. The German Army was probably the best in Europe when the conflict began in 1914, and in spite of heavy casualties on the Eastern and Western Fronts it was still a formidable adversary. The Germans were well trained, disciplined, and led by professionals imbued with a tradition of excellence that stretched back to the 18th century and Frederick the Great. The German Army was also ethnically homogeneous, sharing fundamentally the same basic language and culture. The German commanders did not have to worry about ethnic minorities trying to desert as soon as they had an opportunity.

German General Felix Ludwig Von Bothmer’s South Army slowed Brusilov’s advance, as did General Alexander von Linsingen’s troops on the Russian right in the vicinity of Kovel. The Germans fought well. When they did have to retreat, they did so with discipline. Their morale was far better than that of the disintegrating Hapsburg forces.

By mid-July, the Austrian Army had become so disrupted by Brusilov’s Offensive that they conceded strategic planning to the Germans. From that point forward, all strategical decisions on the Eastern Front came from the Germans.

The Russians had made enormous gains, and at that point it would have been wise to consolidate their territorial gains and brace themselves for the inevitable German counterthrusts. As it was, the Russian advance in the sector south of Kovel had ground to a halt. But Brusilov’s superiors pressured him to continue his advance. They believed that if Brusilov continued to press his attack he just might succeed in knocking Austria-Hungary out the war. It was a matter of human nature. The Russians believed that one more push might achieve victory over the Austrians.

The second phase of the Brusilov Offensive began on July 28 and continued into September. Once again the Russian Army enjoyed an initial period of success. By early September Brusilov’s troops had advanced an average of 60 miles into enemy territory. In some locations they succeeded in advancing up to 100 miles. Almost all of Bukovina was taken, as well as sizable chucks of Galicia. During this impressive advance the Russians had captured 350,000 Austrian prisoners, 400 artillery pieces, and 1,300 machine guns.

Eventually, however, the Russian offensive wound down. German resistance had gradually been stiffening, and keeping up the momentum made it increasingly difficult for the Russian armies to stay supplied so deep in enemy territory. This was because the railroads in Eastern Europe were not as developed as those in Western Europe. Basically, the Russians used transport methods from the Napoleonic Era.

Stanley Washburn, a war correspondent covering the Brusilov Offensive, gave a graphic picture of the logistics involved. “Miles and miles of peasants’ carts bearing food, provender, huge loaves of bread, were succeeded by four-horse wagons piled high with regimental and staff baggage,” wrote Washburn. “These, in turn, turned aside to let the field telegraph outfit pass… Perhaps behind them a long column of two-wheeled, two-horse carts holding small arms ammunition passed tumultuously over rough cobbled stones.”

Yet this rattling, axle-groaning procession had to give way to long columns of brown-clad troops marching to the front. The wagons had to pull over to the side of the road to let the infantry go past, battalion after battalion of men whose scissoring legs kicked up great billowing clouds of dust. Indeed, Washburn noted that the soldiers tanned faces had become “gray with the fine, white dust of the road.”

Those dry conditions were bad enough, but the roads turned into a viscous soup when pummeled by sudden thunderstorms. Washburn was lucky in that he was riding in that rarity of rarities on the Eastern Front, an automobile, but even a car could get into trouble. During a nocturnal thunderstorm, the reporter had an almost surreal experience.

“In two minutes we were wallowing in mud six inches deep, with wheels spinning and smoking tires filling the air with the smell of superheated rubber,” he recalled. “One instant the entire landscape would be thrown into vivid relief by the flash of lightning, and the next, half blinded by the glare, we would be staring into blackness.”

Encouraged by Russian successes, Romania entered the war that same August. But joining the Allies proved to be a debacle for both the Romanians and the Russians. Romania hoped to have a share of spoils when Austria collapsed, particularly the region of Transylvania. Unfortunately for the Romanians, the Germans had long anticipated such a move and had planned accordingly. The Romanians initially invaded Transylvania, occupying almost all of the territory, but their triumph was brief. In a series of deft strokes the Germans sent the ill-prepared Romanian Army back over its own border; the Romanian soldiers hardly knew what hit them.

Having sown the wind, the Romanians reaped the whirlwind. The Germans invaded Romania proper, defeating its army and occupying the whole country. A remnant of the Romanian forces managed to retreat to Moldavia, but few countries had been vanquished as quickly as Romania. The catastrophe also gave Russia additional woes. From that point forward, Russia’s front with the Central Powers was considerably lengthened.

In the meantime, Stavka added two new armies to Brusilov’s command. These were the Russian Third Army and Guards Army. The Guards were among the most elite in the Imperial Russian Army. The Preobazhensky and Semenovsky Guards had impressive pedigrees that stretched back to their formation by Czar Peter the Great in the 17th century.

The Guards were ordered to capture Kovel. On paper, at least, it seemed as if these elite warriors, of whom there were 60,000, would be able to fulfill their assignment. Unfortunately, it was a tradition for Guards units to be officered by aristocrats; indeed, even Romanov royalty usually had a stint in the Guards. Nicholas had served in the Guards when he was heir to the throne two decades earlier. But most of these bluebloods took little interest in real soldiering, although there were notable exceptions.

To many Guards officers, life in the military was mainly a time to drink, socialize, and womanize. General Vladimir Bezobrazov, an old comrade from the czar’s own military stint, declared that the Guards should only be “commanded by people of class.” He also was on record saying that the Guards never retreated.

This kind of romantic attitude might have worked in the preceding centuries, but it was a wrong-headed anachronism in the fire and blood of World War I. The Germans harbored no romantic illusions at Kovel, and they knew how to use the terrain to their best advantage. The low-lying area was one vast swamp.

There were three causeways across the swampy land, each dotted with German machine-gun nests. Attacking troops would have to run a gauntlet of fire—a storm of lead so intense that nothing would likely survive. Although the Russians might have undertaken a flank attack, such a maneuver was a time-consuming process; besides, it was deemed too cowardly for the upper-class Guards. Grand Duke Paul Romanov, the czar’s uncle and the Guards’ commander, gave his approval for the assault.

The Guards would attack along each of the three causeways. The results were predictably horrific. The very cream of the Russian Imperial Army was sacrificed uselessly in a series of costly, headlong attacks. Some of the Guardsmen jumped off the raised paths and into the swamps, seeking shelter from the hail of bullets. But many who chose that option were quickly sucked under water by the quicksand-like muck. Some managed to wade through the muck only to be picked off by German rifle fire.

The surviving Guards somehow managed to get across and establish a bridgehead on the Kovel side. An attempt to send the cavalry across to enlarge their toehold failed because the troopers, who were unnerved by the slaughter, flatly refused to advance. Without support the bridgehead was doomed to failure. The survivors were forced to abandon their hard-won gains and retreat back over the causeways to their starting points.

These elite soldiers had suffered dreadfully. For all intents and purposes, the Guards regiments were so decimated they practically ceased to exist. They suffered a casualty rate of 70 percent. Even Czar Nicholas was shocked out of his usual apathetic stupor. Bezobrazov “ordered an advance across bogs known to be impregnable,” Nicholas wrote to his wife. “His rashness … let the Guards be slaughtered.”

Bezobrazov was relieved of his command, but the damage was done. The Guards were the “praetorians” of the monarchy who would defend the Romanovs in times of trouble. But now the defenders had been uselessly slaughtered. Those who survived the ordeal were bitter and resentful. When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, the Guards mutinied and joined the revolution.

The Russian offensive began to lose steam, and it did not help that there was no real commander in chief to coordinate the army’s moves and furnish direction by keeping close watch on strategic and tactical developments. Czar Nicholas, the nominal commander in chief, was completely unqualified for the high post he occupied. He had assumed control at the urging of Czarina Alexandra, who had unrealistic fantasies of her husband as a “war lord.”

Nicholas did approve of the offensive, but he then retreated into a kind of apathetic trance. The czar, who had taken on more than he could handle, was exhausted and, some believed, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He was increasingly incoherent. “Brusilov is firm and calm,” said Nicholas, adding, “Yesterday I discovered two acacia in the garden.” It probably did not help that he was taking a mixture of henbane and hashish in tea to calm his nerves.

Worse still, at least from the viewpoint of the Romanov dynasty, Nicholas was at Stavka headquarters, roughly 500 miles from the capital at St. Petersburg. That meant that Alexandra ruled in his place, and her unofficial appointment was an unmitigated disaster. She was emotionally unstable, picking ministers on advice from the disreputable mystic Rasputin.

By September 20 the Brusilov offensive had exhausted its momentum. The Russians had achieved some tremendous successes, yet at a horrific cost in lives. In the Brusilov Offensive, the Russians suffered at least 500,000 killed, wounded, or captured. Some sources put Russian losses as high as one million men. In comparison, the Austrians lost upward of 1.5 million men.

In three years of war on the Eastern Front, Russian losses had been catastrophic. Both the Russian military and the Russian people had reached the limit of what they could endure. The following year they would cast off the chains of autocracy and rise up in rebellion against the Romanovs.