By Joshua Shepherd

As their landing craft plunged through heavy surf on the morning of June 6, 1944, it was obvious to the men of Company A, 116th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 29th Infantry Division that the coming hour would be the gravest test of their lives. Assigned to the first wave of assault troops landing on Omaha Beach’s Dog Green sector, the troops were the spearhead of a massive Allied invasion aimed at breaking Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

As the landing craft approached the beach, the soldiers inside could hear the telltale sound of machine-gun rounds striking the raised ramps. Private George Roach recalled that he and his fellow soldiers were well aware that their assignment to the first wave would result in heavy casualties. “We figured the chances of our survival were very slim,” recalled Roach.

At 6:30 am the landing craft carrying Company A quickly closed the distance to the beach. When it was about 30 yards offshore, the flat-bottomed vessel struck a sandbar. As the ramps were lowered, the troops were fully exposed to the fury of the German machine guns. Many of the first men who exited the landing craft were slain by machine guns positioned to have interlocking fields of fire. Their lifeless bodies toppled into the water. Some men chose in their desperation to jump overboard instead of exiting the front of the craft. Once in the water where they were weighed down with their equipment, they faced a life-and-death struggle to keep their heads above water. They thrashed about while strapped to heavy loads. Those who could not get free of the loads drowned.

Struggling forward through a hail of machine-gun and shellfire, the survivors desperately sought cover behind tank obstacles placed by the Germans. Enemy positions were well concealed, and the hapless riflemen of Company A, unable to effectively fight back, fell in mangled heaps. Terrified and demoralized, the green troops of Company A had entered the worst killing zone on Omaha Beach. “They’re leaving us here to die like rats!” screamed Private Henry Witt above the steady roar of enemy fire.

Since Germany’s declaration of war on the United States on December 11, 1941, an Allied assault against continental Europe was inevitable. Beginning with Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, the Allies maintained their momentum against the Third Reich with landings in Sicily and Italy in 1943. In this way, Anglo-American forces battered away at the edges of an overextended Nazi empire.

But perhaps the greatest prize of the war remained occupied France. If the Allies could establish a beachhead, they would have an ideal path to the Ruhr industrial region of western Germany. In March 1943 the Allies selected British Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick Morgan to serve as chief of staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, or COSSAC. Morgan and his staff immediately set to work developing preliminary plans for an invasion of France.

Formulating a workable scheme for what promised to be the largest invasion in military history was a herculean logistical endeavor. Morgan’s staff performed the unheralded but vital task of number crunching that would be done on a monumental scale. Allied planners determined the number of troops, tanks, and aircraft needed for such an operation. They tabulated men and matériel in excruciating detail. Individual supplies numbering in the millions, ranging from ammunition, rations, medicine, tires, and boots, would enable a modern army to carry the war to occupied France.

Morgan further assessed the suitability of landing sites in the far reaches of Western Europe. Although an intuitive guess would place an Allied landing somewhere on the north coast of France, Allied planners explored the possibility of launching an invasion anywhere from Denmark to the Spanish border. From a practical standpoint, though, Allied planners focused on northern France, which possessed suitable beaches on the Pas-de-Calais and Normandy coasts.

The Pas-de-Calais region, situated a mere 20 miles from Britain, was a superficially inviting target. Any invasion there would promise a quick crossing of the English Channel, could be well supported by Allied air forces, and would find beaches suitable for an amphibious landing. Yet it became alarmingly clear from Allied reconnaissance flights that the enemy expected an attack on the Pas-de-Calais. Because of this the Germans had constructed superb fortifications in the region, making it the most heavily defended sector in occupied France.

Allied planners, therefore, chose the coast of Normandy for the landings. Although reaching Normandy would require a 100-mile crossing of the choppy and unpredictable English Channel, a series of beaches stretching west of Caen would afford ideal sites for initial landings. Furthermore, Allied planners believed that the port of Cherbourg, situated just west of the proposed landing sites, could be seized in short order and provide the Allies a deep-water port for the resupply of invasion forces. Just as important, the Normandy coast appeared to be lightly defended by second-rate German conscripts.

Morgan’s staff set in motion in late 1943 an epic and irreversible course of events for what became known as Operation Overlord. Although the massive buildup of men and supplies proved to be a frustratingly slow process, the Russians were loudly clamoring for the Allies to open a second front against Nazi Germany. The leaders of the three primary Allied powers—the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union—held a series of strategy meetings beginning November 28 in Teheran, Iran. At the meetings the three leaders hammered out a strategy to open a new front and assist the hard-pressed Russians.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was deeply suspicious of the intentions of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The Germans had badly mauled Russian forces on the Eastern Front in the two years following the launch of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1942. In particular, Stalin was annoyed that the Allies had not yet named a supreme commander to oversee the planned Anglo-American invasion of France. To show good faith, Roosevelt announced in the wake of the conference that U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower would serve as the supreme commander for Operation Overlord.

While the Allies planned the Normandy landings the high command of the German Army, known as Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, put its talented military engineers to work hardening the coastal defenses of northern France. Legions of German and French laborers worked tirelessly with pick and shovel to construct one of the most imposing defensive lines in history.

Stretching from the tip of Jutland to the border of neutral Spain, the Germans erected a series of fortifications known collectively as the Atlantic Wall. They used millions of cubic yards of steel-reinforced concrete to build fortresses, bunkers, and pillboxes. Defended by nearly a million men, the Atlantic Wall by mid-1944 bristled with heavy artillery, mortars, and machine guns.

The Germans had great difficulty, however, finalizing their strategy for defending against Operation Overlord. While the Atlantic Wall was being built, a major disagreement arose between Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the supreme commander of German forces in Western Europe, and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the commanding officer of Army Group B overseeing the German forces in northern France.

Rundstedt favored a measured approach to confronting a possible invasion. The senior commander believed that the powerful guns on Allied warships would furnish a protective umbrella for the Allied units coming ashore. When the Allies had moved inland beyond the protective cover of the naval guns, the German panzer formations could maneuver in such a way that they would achieve a decisive victory over the Allies.

For his part, Rommel believed it was imperative to contain the Allies on the beaches. He believed that the Allies’ clear advantage in tactical air power would make it impossible for the German panzer formations to maneuver as set forth in Rundstedt’s strategy. If the Allies were allowed to establish a firm foothold on the beaches, Rommel feared they would win the war in France because of their overwhelming advantage in men and matériel. “The high-water line must be the main fighting line,” said Rommel.

The disagreement was compounded by meddling by German leader Adolf Hitler. He insisted on retaining direct control of Germany’s armored and mechanized reserves in France. This meant that Rommel would need Hitler’s authorization to commit the four armored divisions that constituted the Wehrmacht’s strategic reserve in France. The armored divisions were billeted hundreds of miles from the coast.

Eisenhower did not have a strategic conflict similar to that the German generals faced because he had been given greater strategic authority than his German counterparts. He was well suited for the job at hand because of his tireless devotion to duty and his exemplary strategic and administrative skills.

Born in Texas, but raised in Kansas, Eisenhower graduated from West Point in 1915. Although he lacked combat experience in World War I, he was an accomplished staff officer who earned high praise from his superiors. Many of his contemporaries, including General Douglas MacArthur, considered Eisenhower to be the best officer in the U.S. Army at the time. “When the next war comes, he should go right to the top,” said MacArthur.

MacArthur was right. Eisenhower led Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942. After that, he commanded the subsequent Allied forces during the invasion of Sicily and southern Italy in 1943. Eisenhower was popular with U.S. officers and enlisted men and with his counterparts in the British Army. After being appointed supreme commander, he tackled Operation Overlord with an inspiring blend of confidence and eagerness.

The Allies steadily built up their forces in England in the months leading up to the invasion of France. The invasion was possible in large part because of the industrial might of the United States. Factories and shipyards churned out ships, tanks, and trucks, while logistics personnel stockpiled mountains of matériel and rations needed to sustain the troops. Fields and farm lanes throughout England were used as temporary storage sites. Security throughout England was tight, even though it was impossible to completely shield the preparations from German reconnaissance planes.

Allied technological innovation also was on full display. One of the most vital recent inventions was the Landing Craft, Vehicle Personnel (LCVP). Built by Higgins Industries, the landing craft was more commonly known as the Higgins boat. The Higgins boat was a shallow-draft, plywood vessel designed for amphibious landings. Capable of carrying 30 assault troops and their gear, the Higgins boat played a crucial role in the Normandy landings.

The U.S. Army intended to use a curious apparatus to get its armor ashore. First developed for British forces, the duplex drive (DD) amphibious tank consisted of a collapsible canvas shroud that transformed a 33-ton M4 Sherman tank into an amphibious vehicle. By raising the canvas shroud and using the tank’s engine to power twin propellers, the DD system would give the infantrymen close armor support on the Normandy beaches. To ensure that it performed as intended, the Allies put the DD through rigorous amphibious exercises off the English coast. Although the DD system performed flawlessly in the tests, they were conducted in relatively calm waters. Whether they would perform as well in rough waters was unknown.

Final plans called for crushing firepower to be brought to bear directly on enemy positions before the landings. The U.S. Army Air Corps intended to conduct saturation bombing of German coastal positions in Normandy in the hope that the daunting fortifications of the Atlantic Wall might be softened up before the infantry hit the beaches. Once the bomber crews had done their job, Allied surface ships would swing into action, pounding coastal defenses into submission. Landing Craft Tank (Rocket) platforms would then contribute their firepower in the form of rocket salvos intended to keep the enemy hunkered down while the landing craft sped to shore. With any luck, the shell-shocked German defenders would be quickly overrun.

All told, the Allies would land simultaneously on five beaches, forever immortalized by their iconic code names. To the east, British and Canadian troops would strike three landing sites. From left to right, the British 3rd Division would attack Sword Beach, troops of the 3rd Canadian Division would assault Juno Beach, and the British 50th Division would seize Gold Beach.

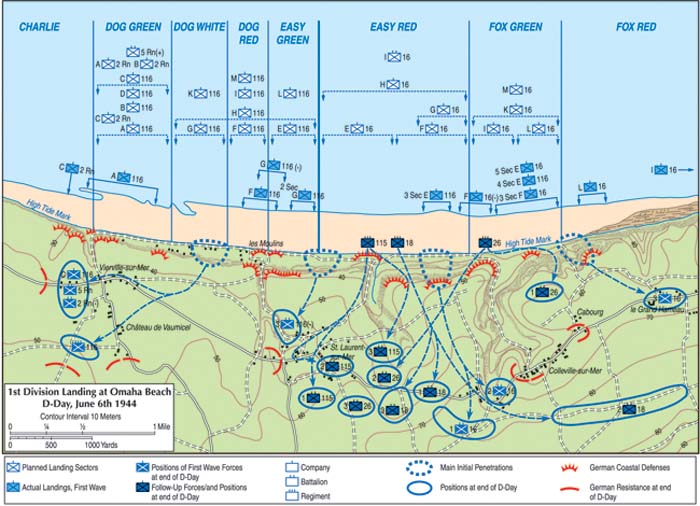

In the American sector to the west, the 1st U.S. Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley was assigned two landings sites. On the Allied far right, the 4th Infantry Division would attack at Utah Beach, where it would be in a position to cut across the neck of the Cotentin Peninsula and isolate the vital port city of Cherbourg. To its left, elements of the 29th and 1st Infantry Divisions would strike a six-mile-long stretch of sand flats known as Omaha Beach. Each assault company on Omaha Beach was assigned to one of eight sectors: Charlie, Dog Green, Dog White, Dog Red, Easy Green, Easy Red, Fox Green, and Fox Red.

Allied planners expected Omaha Beach would prove to be the most difficult landing of the Normandy invasion. Landing at low tide, assault troops would face a dizzying maze of German obstacles before they reached dry ground. The shallows bristled with wooden stakes tipped with mines and steel hedgehogs. The so-called Czech hedgehogs were antitank obstacles made of metal angle beams or I-beams designed to tear the bottom of boats at high tide. As the men moved forward, the only cover available would be a thin natural bank of stones called shingle. Washed ashore for millennia by the waves of the English Channel, the shingle embankment was no more than three feet high. Beyond the shingle lay a daunting no-man’s land of bleak sand, which was 300 to 400 yards deep with no protection. The Germans had 85 machine-gun positions to sweep Omaha Beach.

Once the sand flats were successfully negotiated, troops would encounter a five-foot seawall topped by a nearly impassable barrier of tangled barbed wire. Sheer bluffs rising 100 feet commanded the entire beach. The bluffs were sewn with mines and crowned by some of the most formidable concrete bunkers of the Atlantic Wall. Allied planners had instructed the infantry assaulting Omaha Beach to secure five “draws,” which were passages through the bluffs. The only way the armor could get off the beach was through the draws.

The troops were cautiously optimistic that they would face relatively weak resistance at Omaha. Allied intelligence indicated that the German 716th Division, an inexperienced second-rate unit composed of conscripts from occupied parts of Poland and Russia whose morale was believed to be poor, would put up only token resistance.

Allied planners assured the attacking troops that the enemy positions would be pulverized before they made their assault. “The battleships would blow everything off the map—pillboxes, artillery, mortars, and the barbed-wire entanglements,” Lieutenant William Dillon of the 26th Infantry said the troops had been told. “Everything would be blasted to smithereens—a pushover.”

Despite such optimism, the English Channel’s violently erratic weather patterns would complicate matters for the high command. Due to the need for suitable tides, the attack had to occur during the first week of June or be delayed a minimum of two weeks. The attack was initially scheduled to take place on June 5, but high winds and rough seas forced a postponement. Eisenhower and his senior officers met to discuss their options late in the evening on June 4. Given the unfortunate run of hideous weather, a number of the officers considered an immediate invasion too much of a gamble. But when intelligence officers announced a window of clear weather for June 6, Eisenhower decided to go forward with the invasion.

The Western Naval Task Force, which was composed of 931 vessels, supported the American infantry regiments that would assault Omaha and Utah Beaches. The bigger ships steamed out on June 3 and were joined by the rest of the task force over the succeeding days. For the assault on Omaha, the task force planned to use a wide range of surface vessels, including battleships. Although battleships were becoming increasingly obsolete by 1944, they were perfectly suited for coastal bombardment.

Three Allied paratroop divisions, the U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne and the British 6th Airborne, conducted parachute drops on the night of June 5 behind German lines in Normandy. The paratroopers were tasked with seizing bridges, crossroads, and road hubs behind the landing sites. They suffered heavy casualties in their quest to deny the Germans the ability to reinforce their frontline troops defending the targeted beaches.

At first light on June 6, a massive air armada that included B-17 bombers roared over the Normandy coastline. The bombers pounded German positions on the bluffs overlooking the landing sites for two hours. German soldiers huddled in bunkers or trenches as deafening explosions shook the ground.

When the invasion fleet was within a dozen miles of the beaches, the ships began sending landing craft to shore. U.S. Army officers had hoped to get closer to shore before launching the craft, but the top brass chose to launch them well back from the shore in order to protect the fleet from German fire. This resulted in 10 landing craft swamping in the rough seas. Allied rescue craft did their best to retrieve the water-logged infantrymen. Meanwhile, the rest of the landing craft headed for shore.

The surface ships also opened fire at dawn. Targeting German positions along the bluffs that commanded Omaha Beach, the battleships Texasand Arkansas, supported by an escort of cruisers and destroyers, unleashed a deafening barrage that thundered across the surface of the English Channel.

The battleships possessed fearsome firepower in the form of 10 14-inch guns on the Texas and 12 12-inch guns on the Arkansas. As the big guns belched great clouds of smoke and flame, infantry in nearby landing craft were heartened by the show. Lobbing explosive shells that weighed as much as 1,400 pounds, the ships pounded the bluffs above Omaha Beach, which were soon wreathed in dense clouds of smoke and dust. As the landing craft approached the beach, the battleships ceased fire. At that point, the rocket ships unleashed an estimated 14,000 rockets in a matter of minutes.

When the Allied naval bombardment and aerial bombing stopped, dazed German troops emerged from deep within bunkers to man their fighting positions. Although the assault troops had been led to believe that they would face second-rate troops, Allied intelligence had discerned, albeit too late, that the beach was defended by the more resilient troops of the newly formed 352nd Division.

The 352nd contained a core of veterans who had gained combat experience on the Eastern Front. After the formation of the division in the autumn of 1943, the troops expected to be sent to fight the Russians but soon learned that they would be sent to Normandy. They mistakenly believed it would be a relatively quiet assignment.

The men of the 352nd Division realized by early summer that the chance for an Allied invasion in Normandy was likely. High-ranking German officers grew anxious that the heights overlooking Omaha Beach were vulnerable to capture by the Allies. By the morning of June 6, the beach was defended by elements of Colonel Ernst Goth’s Grenadier Regiment 916, one of the toughest German units on the coast, as well as gunners from the 352nd Artillery Regiment.

When the smoke from the bombers and naval guns lifted, it revealed the complete failure of the Allies to soften up the German positions. The B-17s, which had been designed for high-level bombing of strategic targets, had largely missed the mark and dropped most of their ordnance behind the German positions. As for the naval artillery, it had failed to do serious damage to the well-engineered German fortifications. The bulk of the noisy rocket salvo fell harmlessly in the shallows in front of Omaha. Despite the unparalleled display of firepower, German defenses were largely unscathed. It was an unexpected and ominous development.

Outright bad luck did not help matters. When the DD tanks began launching, affairs quickly degenerated into a fiasco. Set afloat in violent breakers, the Shermans foundered in high waves and sank to the bottom of the sea. Lucky crew members climbed out of the tanks before they went under; however, those who remained trapped inside the 33-ton behemoths perished. Only a relative handful of Sherman tanks, taken closer to shore by quick-thinking officers, succeeded in landing on the beach. For the grim task of assaulting Omaha, the infantry was largely on its own.

As the assault boats plunged through the surf, the men crammed aboard suffered immensely. The choppy seas ensured that the GIs were drenched to the bone and violently seasick. Many of the Higgins boats were leaking badly, and in an effort to stay afloat the troops frantically bailed seawater with their helmets.

Near the western end of the beach, Company A was right on target as it neared its assigned landing zone at Dog Green. But adjacent companies, whose landing craft were pushed off course by strong currents, were badly out of position. As the men of Company A prepared to go ashore, they did so without adequate flank support. Germans in the heavily defended Vierville draw concentrated their fire on the isolated company.

The entire operation began to unravel. Before the craft made landfall, they were taken under heavy fire. One unlucky landing craft inexplicably sank 1,000 yards offshore, while the troops onboard activated their life vests and tried desperately to stay afloat. Another ill-fated craft abruptly disappeared in a violent fireball, the apparent victim of an enemy shell.

When the Higgins boats made landfall and dropped their ramps, the horrific realities of combat manifested in seconds. German machine-gun fire swept through the craft. Scores of men were killed and wounded in a matter of minutes. Those still on their feet struggled forward through the water; as they did so, they endured a steady hail of machine-gun fire. Those who survived the enemy fire crouched behind German antitank obstacles. Pinned down in a deadly interlaced field of enemy machine-gun fire, Company A was out of action.

To its left, Companies G and F, which had been forced off target by the waves, came into the beach together, an inviting mass of targets for the German defenders of Les Moulins draw. As the companies waded ashore, they ran a terrifying gauntlet of enemy fire. Sergeant Henry Bare remembered the carnage as sickening. “My radio man had his head blown off three yards from me … the beach was covered with bodies, men with no legs, no arms,” said Bare. “God it was awful.”

The remnants of the two companies inched their way forward across the beach to the seawall, which offered a measure of cover from German machine-gun fire, but little protection from mortar and artillery fire. When they ran into a coiled mass of barbed wire, the men were helplessly stalled. In the chaos of the landings, they had lost their Bangalore torpedoes and were left with no means of forcing their way through the concertina.

Because getting off the beach quickly was a paramount tactical objective, the men had been instructed to simply keep moving and leave the wounded to the medics. Obeying those orders would leave deep scars for survivors. Badly wounded men “would just lay out there and scream until they died,” recalled Sergeant John Robert Slaughter of Company D. Army medics who braved enemy fire to tend the wounded were universally regarded by their fellow soldiers as heroic saints. But the Germans paid no attention to the red crosses emblazoned on the medics’ helmets. They fired at anyone moving on the beach.

The muddled landings played havoc with unit cohesion. Heavy currents nudged Company E off course, and it came in with elements of the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry. The beach was littered with dead and dying American soldiers. Those fortunate enough to make it to the shingle were trapped by a horrific maelstrom of enemy fire. Mortar rounds continued to fall on their position, and officers desperately tried to get the men out of the killing zone. Company E’s Captain Lawrence Madill, his left arm nearly torn off, stayed on his feet and shouted orders for the men to keep moving. As he sprinted across the beach to retrieve ammunition, Madill was shot down. Just before he succumbed to his wounds, his final thoughts were for the safety of his men. Madill gasped, “Senior noncom, take the men off the beach.”

Without further reinforcement and firepower, simply surviving the ordeal was unlikely. As subsequent waves approached the beach, it was obvious that the entire assault on Omaha had turned into a nightmare, and nearly no one arrived at their assigned sector. When Company B hit the beach, it was greeted with a scene of surreal horrors that survivors would never forget. Private Harold Baumgarten witnessed a fellow soldier with a ghastly wound in his forehead. “He was walking crazily in the water,” said Baumgarten. “Then I saw him get down on his knees and start praying with his rosary beads. At this moment, the Germans cut him in half with their deadly crossfire.”

When Company K came ashore, it was accompanied by Brig. Gen. Norman Cota, the second in command of the 29th Division, and Colonel Charles Canham, the commanding officer of the 116th Infantry. Canham was keen to kill Germans personally. When he charged ashore with his Browning Automatic Rifle, he received a nasty wound to his hand. Refusing medical treatment, he drew his sidearm and stormed ahead.

On the eastern half of Omaha Beach, which was assigned to the 16th Infantry, the landings had gone no better. Private H.W. Shroeder was horrified by what he saw as the ramp on his landing craft dropped. He and his fellow soldiers slowly worked their way across the beach, using the massive hedgehogs for cover. When they finally reached the seawall, there was little room for more panicked men. “There were GIs piled two deep,” recalled Shroeder.

The disorganized companies of the 16th Infantry were badly mauled as they struggled forward. Crouching behind the seawall, the survivors of Company F had lost most of their weapons in their effort to get out of the water. As for Company I, one-third of its men had been killed. When Captain Joe Dawson of Company G came ashore, he was appalled by the sight. “As I landed, I found nothing but men and bodies lying on the shore,” he recalled.

The assault troops also experienced a traffic jam with their vehicles. Demolition teams, which also had been decimated by enemy fire, had been able to blow only a half-dozen paths through the beach obstacles. The tanks, trucks, and bulldozers that had come ashore were trapped on the beach, easy targets for the Germans. The beachmasters halted further vehicle landings at 8:30 am until more paths could be opened.

For the Germans situated on the heights, the beach below presented a target-rich mass of men. At the German bunker known as Widerstandsnest 62, Private Franz Gockel, whose machine gun had been destroyed by an artillery shell, grabbed a rifle and resumed firing on the Americans scrambling for cover on the beach below. When the GIs crowded behind the seawall, German mortar teams targeted them. “They had waited for this moment and began to lay deadly fire on preset coordinates along the sea wall,” said Gockel. As American landing craft began turning away from the beach, Gockel and his comrades thought the Americans were beginning to withdraw.

Despite the one-sided fight on the sand flats of Omaha Beach, German troops along the rest of the Normandy coast were hard pressed. General of Artillery Erich Marcks, who commanded the LXXXIV Corps, found himself overwhelmed by simultaneous landings on five beaches in his front. He had always regarded Omaha as the weakest sector in his line, and it was obvious that he could expect no immediate armor support. German air cover was virtually nonexistent. Marcks threw forward just a portion of his infantry reserves; it seemed that the attack on Omaha was being handily repulsed.

On the deck of the cruiser Augusta,Lt. Gen. Bradley, shocked by initial reports, was of much the same opinion. Although the American landings on Utah had gone miraculously well and the British and Canadian troops were making good headway in their sector, the assault on Omaha Beach seemed to have degenerated into a disastrous and bloody nightmare. Hardly any of the units had landed where they were supposed to land. What is more, the initial casualty estimates were appalling and it appeared doubtful if the disorganized survivors would be able to push inland.

Bradley was giving serious consideration at mid-morning to pulling the plug on the entire operation at Omaha Beach and transferring subsequent waves to the British landing zones. The tactical solution to the bloody impasse on Omaha Beach came not from the top brass, but from intrepid officers, non-commissioned officers, and grunts; for example, when Colonel Canham arrived at the stalled line of GIs on the beach, he was a storm of energy. He shouted, cursed, and threatened the men to get them moving. Canham knew that if the assault troops remained paralyzed behind the seawall, they would make easy targets for enemy machine-gun and mortar teams, which had presighted every inch of Omaha Beach. Despite the high casualties that were sure to result if the attack was pressed forward, there was simply no other choice. “Get the hell off this damn beach and go kill some Germans!” he bellowed.

The captains of the U.S. destroyers stationed offshore were exasperated at the sight of the mauling experienced by the infantry. They took the initiative to move their vessels closer to shore to furnish badly needed fire support. About a dozen destroyers risked grounding on the sandbars and delivered a punishing fire to German positions on the bluff.

Brigadier General Cota was equally conspicuous, rallying the demoralized Americans for a final push up the bluffs. Cota personally directed the placement of Bangalore torpedoes that blew a hole in the barbed wire above the seawall. He was one of the first men who charged through the gap. Rushing forward through a storm of enemy mortar fire, Cota miraculously remained on his feet after five men fell beside him. Realizing that the beach draws were too heavily defended to take by frontal attack, Cota ordered his men to storm the steep bluffs.

Junior officers and non-coms had already reached the same conclusion and began leading small groups of men in a desperate bid to climb the heights above the beach. The momentum of the fight finally shifted when the troops, gripped with a powerful mix of fury, adrenaline, and the sheer will to survive, rushed forward in small groups and punched through the defenses behind the seawall.

The hillside was heavily mined, and advancing infantry would pay dearly for every inch of ground. The minefields would come to be littered with mangled GIs who had fallen victim to the hidden killers. But as the Americans began locating and marking safe passages, the German grip on the bluff began to weaken. GIs rousted Germans from pillboxes, bunkers, and trenches by wildly shooting at any defender brave enough to make a run for it. With a measure of vengeful irony, American troops turned captured machine guns on the backs of Germans who had made Omaha Beach a veritable slaughter pen.

Sergeant Warner Hamlett of the 116th and a squad of men from Company D hit the German positions with an assault that would be repeated all across the bluffs. The men inched their way between German pillboxes, attacked the connecting trenches, and then worked their way to the rear of the pillboxes. The troops tossed hand grenades through apertures and then rushed inside to kill the survivors. “The bravery and gallantry of the soldiers was beyond belief,” said Hamlett.

That morning and into the afternoon, average soldiers fought their way up the bluffs and pried the German defenders loose. “Troops formerly pinned down on beaches Easy Red, Easy Green, Fox Red advancing up heights behind beaches,” Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, the commander of the 29th Division, reported at 1 pm.

Considerable tough fighting remained, but Omaha had finally been secured. By mid-afternoon, troops from various units, including the 116th Infantry and elements of the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions, were driving German troops from the coastal villages south of Omaha Beach.

The dearly bought landing site resembled a frightful charnel house. Hundreds of lifeless corpses rocked in the incoming tide and carpeted the beach. Sergeant Hamlett, after being wounded on the bluffs, limped for the shoreline to find a medic. “As I painfully walked back to the beach, thousands of parts of bodies lined it,” he said. “There were floating heads, arms, legs.” Meanwhile, exhausted Navy surgeons on ships at sea worked feverishly to save the wounded, calm the shell shocked, and amputate shattered limbs.

The Americans suffered 4,700 casualties at Omaha Beach. The ill-fated Company A of the 116th, which was virtually destroyed in the assault, suffered 96 percent overall casualties. Of the total Allied losses on D-Day, one-third had been sustained on the flats and bluffs of Omaha Beach.

But such appalling personal sacrifice had secured a permanent lodgment into Nazi-occupied Europe. While American and Allied troops continued to press the attack into Normandy, landing craft ferried supplies from the fleet, eventually depositing a veritable mountain of matériel on the five landing beaches. In the week following Operation Overlord, the Allies had landed more than 300,000 men and 2,000 tanks in coastal France.

The epic struggle on Omaha Beach proved to be one of the costliest battles of World War II, but it helped set in motion an inexorable chain of events that would lead to the collapse of the Third Reich. Rommel had been correct when he said that the war would be won or lost on the beaches.

For the American citizen soldiers who stormed the Atlantic Wall, D-Day left scarred bodies and seared memories. Those who survived the ordeal then had to endure the 11-month drive from Normandy to the Elbe River that ended with Nazi Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945. Bob Slaughter, who had seen his fellow soldiers in Company D of the 116th Infantry killed wholesale on the fateful morning of June 6, gave credit for victory to the American infantrymen who paid the ultimate sacrifice on Omaha Beach. “They laid it all on the line, and they won the war,” he said.