By Richard Z. Freemann, Jr.

“War is mainly a catalogue of blunders.”

—Winston Churchill (1950)

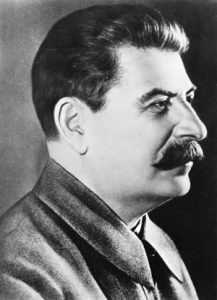

On Sunday, June 22, 1941, as the sun slumbered, 3.6 million soldiers, 2,000 warplane pilots, and 3,350 tank commanders under skilled German command crouched at the border of Soviet-occupied Poland ready to invade the Communist nation Joseph Stalin had ruled with steel-fisted brutality for years.

Shortly after 3 am, in an operation Adolf Hitler called “Barbarossa,” a three-million-man Axis force struck Soviet positions along a 900-mile-long front. German aircraft bombed military bases, supply depots and cities, including Sevastopol on the Black Sea, Brest in Belarus, and others up and down the frontier. The night before, German commandos had snuck into Soviet territory and destroyed Red Army communications networks in the West, making it difficult for those under attack to obtain direction from Moscow.

By the end of the first day of combat, some 1,200 Soviet aircraft had been destroyed, two-thirds while parked on the ground. The poorly led Soviet troops who were not killed or captured buckled under the German onslaught.

Stalin was staggered by the German ambush. Germany’s unannounced act of war violated the nonaggression pact that Hitler and Stalin had signed less than two years earlier and placed at risk the very survival of the Soviet Union.

At first, Stalin insisted that it was just a provocation triggered by some rogue German generals and refused to order a counterattack until he heard officially from Berlin. The German declaration of war finally arrived four hours later.

Hitler justified Barbarossa on the basis that the Soviet Union was “about to attack Germany from the rear.” Eventually, after much dithering, Stalin ordered the Red Army to “use all their strength and means to come down on the enemy’s forces and destroy them where they have violated the Soviet border,” but oddly directed that until further orders “ground troops were not to cross the border.”

The Soviet dictator lacked the heart to inform the Russian people that the Germans had invaded. That bitter task fell to Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, who reported the assault in a radio broadcast more than eight hours after the conflict began. Sadly, Axis bombs and bullets had already alerted millions to the disaster.

Despite the urging of his military officers, Stalin, fearing he would be blamed for the losses, declined to take on the title of commander in chief of the Red Army. He did not even meet with the Politburo until 2 pm on that traumatic day.

Lacking sufficient skilled military leadership, the shocked Red Army reacted slowly and fearfully. As the Germans stormed east and mauled the Soviet troops, Stalin’s generals asked for permission to retreat to reduce casualties, move to defensive positions, and prepare for a counterattack. Stalin refused. His poorly equipped, trained, and led soldiers were ordered to stand their ground regardless of the consequences.

In the first 10 days of combat, the Germans thrust some 300 miles into Soviet territory and captured Minsk and more than 400,000 Red Army troops. At least 40,000 Russian soldiers died each day. Axis forces gained almost total air control and destroyed 90 percent of Stalin’s mechanized forces. Twenty million people who had been living under Soviet control were suddenly living in Axis territory. Many of those in areas previously invaded by Stalin (e.g., Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland) initially welcomed the Germans as liberators.

Stalin seemed close to a nervous breakdown. The losses were so humiliating that, despite being the head of government, he retreated to his summer home and, during several gloomy June days of heavy drinking, refused to answer his phone or play any role in his nation’s affairs, leaving the ship of state to flounder helplessly. On June 28, he muttered, “Lenin left us a great legacy, but we, his heirs, have ****ed it up.”

Senior Soviet leaders mustered the courage to visit Stalin’s dacha on June 30. Upon arrival, they found him despondent and disheveled. He nervously asked, “Why have you come?” Stalin apparently thought that his underlings were there to arrest him. But they, long cowed by the dictator’s brutal intimidation, simply beseeched him to return to work at the Kremlin. He eventually did so.

Certainly, Operation Barbarossa was spawned by Hitler’s hatred of communism and dream of world domination. But Stalin’s many missteps in the previous two years enticed Hitler to attack and contributed significantly to Barbarossa’s early successes. Stalin’s blunders included purging the Soviet military of its leaders, entering into a treaty with Hitler that triggered a world war that subsequently ravaged Russia, launching a bumbling attack on Finland in late 1939, misreading Hitler, adopting a flawed plan of attack on Germany, and ignoring warnings of Hitler’s forthcoming Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.

In furtherance of Lenin’s goal of provoking a worldwide communist revolution, Stalin sought to undermine capitalist governments across Europe. He sought to destroy anyone abroad or at home who might stand in the way of his brand of communism. According to Stalin, “As long as the capitalist encirclement exists there will continue to be present among us wreckers, spies, saboteurs and murderers.”

In a 1937 speech, the “man of steel” (which is what “Stalin” means in Russian) made his brutal stance clear: “Anyone who tries to destroy the unity of the socialist state, who aims to separate any of its parts or nationalities from it, is an enemy, a sworn enemy of the state and of the peoples of the USSR. And we will exterminate each and every one of these enemies, whether they are old Bolsheviks or not. We will exterminate their kin and entire family. We will mercilessly exterminate anyone, who with deeds or thoughts threatens the unity of the socialist state.”

This thinking gave rise to the Great Terror in which Stalin had millions of Soviet citizens arrested for “counterrevolutionary crimes” or “anti-Soviet agitation.” In 1937 and 1938, at least 1.3 million people were convicted of being “anti-Soviet elements.” More than half were executed—on average 1,500 people shot dead each day.

Stalin used the Great Terror to eliminate potential threats within the Soviet military. He removed some 34,000 Red Army officers from service. Of those, 22,705 were shot or went “missing.” Out of 101 members of the Red Army’s supreme leadership, Stalin had 91 arrested and 80 shot. Eight of nine senior admirals in the Soviet navy were put to death. By 1939, he had essentially decapitated the military forces responsible for protecting the Soviet Union from invasion.

In Hitler’s 1925 autobiography, Mein Kampf,he declared both his fierce opposition to Marxism and Germany’s need to acquire more territory to provide “living space” for its people. Hitler made clear that one source of such lands would be “Russia and her vassal border states.”

Following Hitler’s 1933 rise to power in Germany, the fascist policies he implemented were directly targeted against Stalin’s communism. Over the next half-dozen years, in contravention of the Versailles Treaty that basically forbade Germany from rearming, Germany’s military might and expansionist aspirations grew at a fearsome rate. Hitler added to Germany’s territory by absorbing Austria in 1938 and large parts of Czechoslovakia in early 1939. His gaze then fell upon neighboring Poland.

Stalin was right to fret about Hitler’s goal of seizing fertile lands to the east of Germany, including Ukraine. Stalin recognized that the Soviet Union and its Red Army in the late 1930s were not ready for war. He could buy time and seek to retard Hitler’s appetite either by forming an alliance with Germany’s traditional foes, Great Britain and France, or by pursuing a nonaggression treaty with Hitler.

In early 1939, Stalin began negotiations with France and Great Britain aimed at a treaty that would leave Hitler facing opponents to the east and west of Germany. These efforts, however, were impeded by the reluctance of both France and Great Britain to enter into a treaty with a communist nation bent on undermining capitalist democracies and especially one led by an unpredictable and ruthless dictator like Stalin. The negotiations proceeded fitfully.

Several months later, seeking to thwart a treaty among Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, Hitler secretly invited Stalin to discuss a nonaggression pact (the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, named after the two countries’ foreign ministers). Hitler’s covert plan for a late summer attack on Poland, which both France and Great Britain had promised to defend, motivated him to strike a deal with Stalin so that Germany would not face a hostile military to the east.

In late August 1939, Hitler and Stalin stunned the world by announcing that their two nations had agreed to a trade and nonaggression pact. This came about only after Stalin obtained Hitler’s secret promise that the two nations would invade and carve up Poland between them, and Germany would facilitate Stalin’s desire to take over Latvia, Estonia, Bessarabia, and parts of Finland.

On August 19, Stalin justified his unlikely deal with Hitler to the Politburo: “The question of war and peace has entered a critical phase for us. Its solution depends entirely on the position which will be taken by the Soviet Union. We are absolutely convinced that if we conclude a mutual assistance pact with France and Great Britain, Germany will back off from Poland and seek a modus vivendi with the Western Powers. War would be avoided, but further events could prove dangerous for the USSR.

“On the other hand, if we accept Germany’s proposal … and conclude a non-aggression pact with her, she will certainly invade Poland, and the intervention of France and England is then unavoidable. Western Europe would be subjected to serious upheavals and disorder. In this case we will have a great opportunity to stay out of the conflict, and we could plan the opportune time for us to enter the war.

“The experience of the last 20 years has shown that in peacetime the Communist movement is never strong enough for the Bolshevik Party to seize power. The dictatorship of such party will only become possible as the result of a major war.”

Stalin continued: “Comrades, I have presented my considerations to you. I repeat that it is in the interest of the USSR, the workers’ homeland, that a war breaks out between the Reich and the capitalist Anglo-French bloc. Everything should be done so that it drags out as long as possible with the goal of weakening both sides. For this reason, it is imperative that we agree to conclude the pact proposed by Germany, and then work in such a way that this war, once it is declared, will be prolonged maximally. We must strengthen our propaganda work in the belligerent countries in order to be prepared when the war ends.”

So, on August 23, 1939, the cold-blooded, anticapitalist leader who aimed to “Sovietize” the world climbed into bed with the cold-blooded, anti-Bolshevik leader who dreamed of fascist world rule.

On September 1, 1939, more than a million German warriors invaded Poland from the west. Sixteen days later, in accord with the secret August pact between Stalin and Hitler, half a million Soviet troops invaded Poland from the east. Within weeks the Polish nation simply vanished and, having pocketed its territory, Germany and the Soviet Union now shared a common border and responsibility for starting World War II.

In late November 1939, Stalin ordered about one million Red Army soldiers to invade neighboring Finland, a nation of just 3.6 million residents. (Finland had been ruled by Russia until 1918, when anti-Bolsheviks prevailed in a Finnish civil war.) During four months of harsh winter fighting against brave and defiant resistance, more than 200,000 Red Army soldiers died (Nikita Khrushchev said in his memoirs that the figure was closer to a million)—dwarfing the Finns’ military fatalities.

Embarrassed, Stalin entered into an armistice under which Finland surrendered some territory, but the modest Soviet land gain was disproportionate to such vast human losses. Because of its unprovoked attack on Finland, the Soviet Union was expelled from the League of Nations.

Stalin’s earlier purge of his military leaders and the Red Army’s woeful showing in Finland persuaded Hitler that Soviet forces were weak and encouraged him to consider a surprise attack on the USSR. Stalin was painfully aware by 1940 that the Red Army was lacking in leadership, weapons, manpower, infrastructure, training, and war planning. He ordered a massive upgrade of the military to be carried out at top speed. But this would take time, and in the interim care would have to be taken not to provoke Hitler into attacking Russia.

To Stalin’s amazement and discomfort, during the first half of 1940, German military forces stormed through Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and France and drove the humbled British forces back to their island from the European mainland. These rapid victories did not comport with the Soviet leader’s strategic concept that the Western European countries would, to communism’s ultimate advantage, exhaust each other in a protracted war.

Under their trade agreements, the Soviet Union supplied Germany with huge quantities of foodstuffs, raw materials, and oil and acquired from international markets goods Hitler needed but could not otherwise obtain due to Great Britain’s naval blockade of German ports. Ironically, by mid-1940, the Soviet Union was Germany’s most important trading partner.

Stalin’s view at this time was that Hitler’s desire to seize land to the east was motivated mainly by Germany’s need for additional food and natural resources. Thus, Stalin hoped that if the Soviet Union satisfied much of Hitler’s hunger for essential goods the risk of a near-term German attack would be tempered.

Stalin appreciated that a German attack on the Soviet Union was likely to come eventually. He assumed, however, that Hitler would not strike until after Great Britain had surrendered. He believed the British could hold out until at least mid-1942. He also assumed that before attacking the USSR Hitler would demand from Stalin land and resources and that the Führer’s ultimatum would afford the Soviets some time to react with a concession, a preemptive attack, or at least a move to defensive military positions.

During the summer of 1940, Stalin secretly contemplated having the Red Army launch a surprise attack on Germany in 1942. He hoped that by then the Red Army would be stronger as its officers gained experience and it was modernized, and Germany would be weaker from her ongoing battles against Great Britain.

Consistent with his August 1939 remarks to the Politburo, Stalin reasoned that if Germany fell the Red Army would have a clear path to sweep into capitalist Europe and implant communism there. He directed a few top generals to covertly draft battle plans. In October 1940, after reviewing several proposals, Stalin wavered over when—or whether—to launch a preemptive strike, but planning for such an attack continued.

Coincidentally, in July 1940, Hitler asked his generals to develop secret plans for a German surprise attack on the Soviet Union. The Führer’s objectives were to eradicate “Jewish” Bolshevism, gain territory and natural resources to the east, exterminate the Stalinist threat, and eliminate the chance that the USSR would provide aid to Great Britain.

In November 1940, Hitler invited the Soviet Union to join with Germany, Italy, and Japan as a member of the Tripartite Pact, which committed all signatories to align in the event of war with the United States. The German dictator also sought to persuade the Soviet dictator to focus his territorial expansion efforts on the Middle East rather than Eastern Europe.

Because Stalin coveted lands in Europe and wanted Hitler to withdraw Axis troops from Finland, the negotiations failed. These differences convinced Hitler that conflict between his nation and Stalin’s was inevitable.

By December 18, 1940, Hitler’s mind was made up. He ordered his generals to complete detailed war plans “to crush Soviet Russia in a rapid campaign”—code named Operation Barbarossa—to begin in May 1941.

At about the same time, Stalin ordered the Red Army to construct armed fortifications close to the German/Soviet border. When completed, these would be an asset in a preemptive Soviet attack but a liability in a defensive contest triggered by a German blitzkreig. Military convention called for such fortifications to be set a distance inland from the border to protect troops, artillery, and weapons from prompt destruction or capture in the event of a surprise attack and to give the defending military forces room to maneuver.

As spring arrived in 1941, Stalin still had not decided whether or when to launch a preemptive assault on Germany. His generals, however, continued to prepare for such an attack.

In 1941, Hitler took steps to guard his southern flank against a hostile attack in the coming war on Soviet Russia and convinced Bulgaria and Yugoslavia to join the Tripartite Pact. When in early April civil war broke out in Yugoslavia, he sent troops to quell the uprising. His forces also invaded Greece that month to salvage a failed Italian operation there. These relatively brief military operations, however, forced Hitler to delay the start of Operation Barbarossa. It was reset for June 22.

In April 1941, Stalin proudly announced that the Soviet Union had entered into a nonaggression pact with Japan. This significantly reduced the threat of military action against the USSR from the east and allowed Stalin to focus on Germany.

On May 10, Hitler’s Deputy Führer, Rudolph Hess, flew solo to the British Isles and parachuted into Scotland with the objective of negotiating peace between Germany and Great Britain. The British arrested Hess, who had made his flight without Hitler’s knowledge or consent. But Stalin’s suspicious and conspiratorial mind worried that if Hess were indeed on a secret peace mission and Germany ended its conflict with the British, the threat of a German attack on the USSR would balloon.

On May 15, Stalin’s top generals gave him an updated preemptive attack plan declaring that “it is necessary to deprive the German command of all initiative, to preempt the adversary and to attack.” The generals proposed sending troops, planes, and other equipment to the western border in the guise of “training exercises.”

With the risk of a Japanese invasion apparently neutralized, nervous about what Hess was up to in England, aware that Germany was massing troops at his border, and believing that the first nation to attack would likely prevail, Stalin felt the urge to be proactive. According to some historians, he decided to move the Soviet preemptive attack up from 1942 to the coming summer.

Just a few days earlier, in a speech to Red Army military school graduates, Stalin had declared, “Our military policy must change from defense to waging offensive actions.” He then ramped up production of planes and other military equipment, drafted almost a million more men into the armed forces, and began moving millions of Red Army soldiers and their supplies west to be in place by July 10.

Still wary of giving Hitler an excuse to strike first, Stalin sought to conceal his massive military expansion near the German/Soviet border. Soviet propaganda derided rumors of a Russian buildup as “totally fantastic”—the troops were merely training. Yet, out of fear of inciting Germany to attack, Stalin repeatedly refused his generals’ requests to place those western Red Army soldiers on combat alert. He told them, “You must understand that Germany will never on its own move to attack Russia…. If you provoke the Germans on the border, if you move forces without our permission, then bear in mind that heads will roll.”

Stalin’s vulnerability to a preemptive Axis attack in 1941 was increased by the fact that after moving into Poland in 1939, the Soviets had taken down their defensive fortifications near their old border but had not yet completed new ones at the more westerly frontier.

Another problem was that the military supplies and warplanes Stalin had ordered moved to the new border in advance of the planned preemptive strike were now exposed to capture or destruction in a surprise Axis assault.

Moreover, his military communications systems were rudimentary, and his ability to quickly move troops and equipment by road or rail was limited. Additionally, many of his weapons were outmoded. Finally, Stalin had no backup plan addressing how the USSR would defend if Germany struck first.

During the first half of 1941, the United States, Great Britain, and other foreign nations had gotten wind of Germany’s secret plan to attack the USSR. In April, Winston Churchill, no fan of communism, sent an invasion warning to Stalin. President Franklin Roosevelt delivered a similar alert. Stalin also received invasion signals from Soviet spies abroad, the increase of Axis troops on the border, repeated German aircraft incursions into Soviet territory, and the fact that many German diplomats and their families began to leave Moscow.

But Stalin, ever cynical of the motives of others, discredited all of these alarms. The Soviet leader remained convinced that Hitler would not be foolish enough to initiate a two-front war during the first half of 1941, even though by then the only powerful nation Germany was fighting was the beleaguered Great Britain.

Stalin knew that the fall “mud season” and harsh Russian winter dictated that any German blitzkrieg likely to succeed would have to be launched by mid-summer. Thus, he reasoned that if Russia could avoid an immediate attack he would be in position to strike first.

In early June, Stalin’s anxiety about internal threats and traitors bubbled up anew. He once again purged the Red Army leadership, this time of 300 officers, including more than 20 who had received the nation’s highest military honor. As a result, about three-quarters of his field officers had no more than two years of experience in their posts.

In a peculiar June 14, 1941, radio broadcast reflecting Stalin’s paranoia and unwillingness to acknowledge the imminent threat, the Kremlin announced that British rumors of a German attack on the USSR were an “obvious absurdity” and “a clumsy propaganda manoeuvre of the forces arrayed against the Soviet Union and Germany.” This statement troubled Stalin’s surviving generals, for it was inconsistent with their efforts to gear up for the war brewing at the border.

On June 19, 25 German ships abruptly left a port controlled by the USSR, and Stalin grew more nervous. He ordered that his planes on the western frontier be camouflaged within a month but continued to deny permission to place his troops on combat alert.

Seeking some assurance that his nonaggression pact with Hitler would hold, on June 21 (the day before the scheduled blitzkrieg) Stalin instructed his diplomats to contact Germany’s foreign minister to ask why so many German troops had gathered on the Soviet border. Ribbentrop’s staff stubbornly maintained throughout the day that the German diplomat was unavailable. Late that evening, when questioned about rumors of an impending Axis attack, Germany’s ambassador to the USSR simply said he was unable to supply an answer.

Also that evening, a German defector informed a Red Army officer that the blitzkrieg would come the next morning. Stalin panicked. Hitler might actually strike first! But the Soviet dictator reacted inconsistently. He alerted his field generals that a German attack could come on June 22 or 23 and told them to move their troops closer to the border and be on high alert. At the same time, Stalin warned them to prudently prevent “big complications”—war—and “not to yield to any provocation” from the Germans. Did this mean they were to accept an Axis blow and not counterattack? With no further explanation, Stalin went home for the evening.

Operation Barbarossa was launched several hours later with devastating impact on the Soviets. As both sides were gearing up for a preemptive attack, Hitler struck first and caught the Soviets flatfooted. A massive force of nearly four million Axis troops (from Germany, Italy, Hungary, Romania, Finland, Slovakia, and Croatia), 3,350 tanks, 7,200 pieces of artillery, 2,770 warplanes, and 700,000 wagon-pulling horses crashed across a front that stretched 1,800 miles—from the East Prussia-Lithuania border on the Baltic Sea to the border of Romania and Ukraine on the Black Sea.

The Axis attack was astonishing in its speed, scope, and savagery. Soviet divisions, hopelessly outnumbered and outgeneraled, were torn to shreds by the advancing Axis troops. Some five million Red Army troops would be taken prisoner; most would not survive the war. Nazi death squads, known as Einsatzgruppen (“Operational Groups”), swept across the conquered lands in the wake of the combat troops to round up Jews in the towns and villages and kill them.

Stalin’s many errors invited the devastation. Stalin’s target date for his attack on Hitler was tardy by at least two weeks. The Soviet dictator had failed to heed multiple warnings of a German blitzkrieg. Before that, he had rejected a pact with France and Great Britain that, as he acknowledged to the Politburo, would have prevented World War II and probably the June 1941 attack.

Stalin had positioned his combat supplies and undisguised warplanes too near the German border, neglected to develop an adequate military transportation system, and taken down his fortifications at the old Soviet boundary without completing new ones. The Red Army lacked sound defensive plans in the event of a surprise enemy attack.

Stalin failed to order an immediate and comprehensive counterattack early on June 22 and then refused to permit a strategic retreat. His decision to decapitate the Red Army had left him with meek and inexperienced combat leadership. The German attack achieved shocking results during its opening stages, leaving Stalin depressed, disheveled, and drunk.

However, good fortune continued to follow Stalin personally. Despite ruthlessly eliminating all opposition within the Communist Party, killing and starving millions of Soviets in the 1930s and imprisoning millions more, bungling preparations for war with Hitler, and going into depressed hiding for several days after Hitler’s stunning attack, Stalin’s weak subordinates did not do to him in late June what he surely would have done to them had the roles been reversed; he was not arrested, tortured, imprisoned, or shot dead by firing squad.

Stalin was also fortunate in late June that bellicose Japan rejected Hitler’s urgings and chose not to attack the Soviet Union from the east as Barbarossa advanced from the west.

And, although Stalin’s conspiracy with Hitler led to the start of World War II and years of vital communist aid to Axis forces, in the summer of 1941, when Stalin was most vulnerable, two capitalist nations opposed to communism came to his rescue. Great Britain and the United States sent lifesaving military supplies and food to the besieged Soviet leader—something that Stalin was loath to acknowledge.

Stalin was also lucky that Hitler had decided to postpone his Soviet invasion by five weeks to put down uprisings in Yugoslavia and Greece. The resulting belated Axis march on Moscow was thwarted by the snow and bone-cold December weather just a few miles from the Russian capital. An earlier start could have yielded a far different outcome.

Barbarossa was eventually defeated, but not until four years had passed and tens of millions had died. Lacking Stalin’s good luck, the people of the Soviet Union paid a frightful price in death and destruction for his catalogue of blunders.