By David A. Norris

Lieutenant William B. Cushing’s Union Navy steam launch chugged up the dark Roanoke River late in 1864. Any moment, her hand-picked crew expected to hear gunshots putting their mission and their lives at risk. But on that rainy night Cushing’s crew passed one enemy picket post after another and heard nothing. They pushed on to the river town of Plymouth, North Carolina, in search of their target, the ironclad CSS Albemarle. As they closed in on the enemy gunboat, a barking dog shattered the quiet. Jolted awake, sentries hastily fired their muskets at the intruders. Ignoring the musket balls, Cushing steered straight for the enemy gunboat. Fastened to the bow of his launch was an explosive device that his commanders hoped would tip the balance of power in eastern North Carolina back to the Union.

With the exception of the heavily guarded port of Wilmington, the Union took the major coastal towns of North Carolina in early 1862. By the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army had not been able to eject Union troops from their strongholds of New Bern, Washington, Beaufort, and Plymouth. Union success at holding on was not due solely to the Army. Every North Carolina town held by the Union was within the range of U.S. Navy gunboats. Mobile and heavily armed, these floating steam-powered fortresses backed up the army against land attacks.

To break the stalemate, the Confederates placed their hopes in new ironclad gunboats. Union ironclads drew too much water to pass through the shallow inlets along the North Carolina sounds, limiting the North to wooden vessels. The Confederate Navy began building ironclads in 1862 at inland shipyards along the Roanoke, Tar, and Neuse Rivers. Cavalry raiders burned the partially built Tar River vessel in 1863, and construction delays hindered completion of the CSS Neuse. But, in a former cornfield by the Roanoke River at Edwards Ferry, the CSS Albemarle neared completion in early 1864. Union army commanders felt Edwards Ferry was too far inland for a cavalry raid and never ordered a strike on the shipyard. They would come to regret their decision.

Lieutenant Gilbert Elliott of the Confederate Navy was 19 years old when he was given the task of managing the construction of the Albemarle. A law student by profession, Elliott had absorbed considerable knowledge of shipbuilding; his mother’s family owned a shipyard, and as a law clerk in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, he worked for the owner of a shipyard.

After allowing a few months for seasoning the cut timbers, construction began in the spring of 1863. Using designs by John L. Porter, who was famous for his design work on the CSS Virginia, Elliott built a 158-foot-long gunboat. Her 60-foot casemate was octagonal in shape, with the port and starboard sides by far the greatest in length. Two layers of iron plate, two inches thick and seven inches across, were rolled at the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond and brought to the shipyard.

Elliott struggled with the supply and machinery shortages that plagued all Confederate shipbuilders. He scrounged up three portable sawmills, keeping one at the yard and shifting the other two wherever he could find suitable timber. Oakum was practically unavailable, so they caulked the gunboat’s seams with local cotton. There was only one painfully slow drill to make river holes in the iron plating. Fortunately, Peter D. Smith, who owned the cornfield where the Albemarle was under construction, was also a talented inventor. Smith devised a drill that pierced the armor plates in four minutes rather than 20.

Elliott installed two 6.4-inch Brooke rifles onboard. The guns could rotate to fire through a porthole at the end of the casemate or an opening on either side. The vessel’s third weapon was a heavy oak prow intended to serve as a ram. The ram jutted 18 feet forward from the bow and was covered with iron.

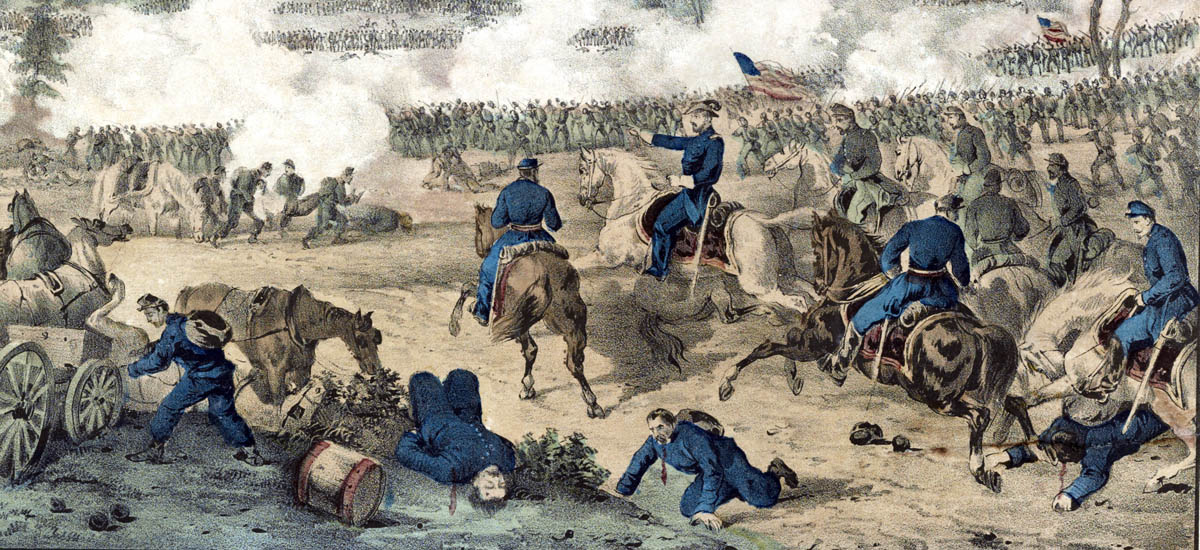

Elliott was desperate to finish the vessel in time to aid Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s siege of the river port of Plymouth, North Carolina. Hoke’s three brigades, detached from the Army of Northern Virginia during the wintertime lull in the Virginia campaigns, bogged down before Plymouth’s land defenses. Aiding the defense of Plymouth were four Union Navy gunboats under Lt. Cmdr. Charles W. Flusser: the USS Southfield, Ceres, Whitehead, and his own Miami. Hoke had little chance of success with the gunboats adding their firepower to the forts guarding the town.

When the Albemarle headed down the Roanoke River, carpenters and blacksmiths rushed to finish their work as portable forges smoldered on the deck. Unable to steer in the narrow river, the ram floated downstream stern first, dragging chains from the bow to steady the hull. Cooke lost 10 hours when the engines broke down.

There was much worry about the obstructions placed in the river by the defenders of Plymouth. But the Roanoke was running unusually high. Ten feet of water flowed over the obstructions; the water level was just enough to get the Albemarle with her 9-foot draft over them.

Arriving at Plymouth at 2:30 am on April 19, 1864, Cooke came under fire from a Union outwork, Fort Gray. He ignored the firing from shore and steered for the Union vessels.

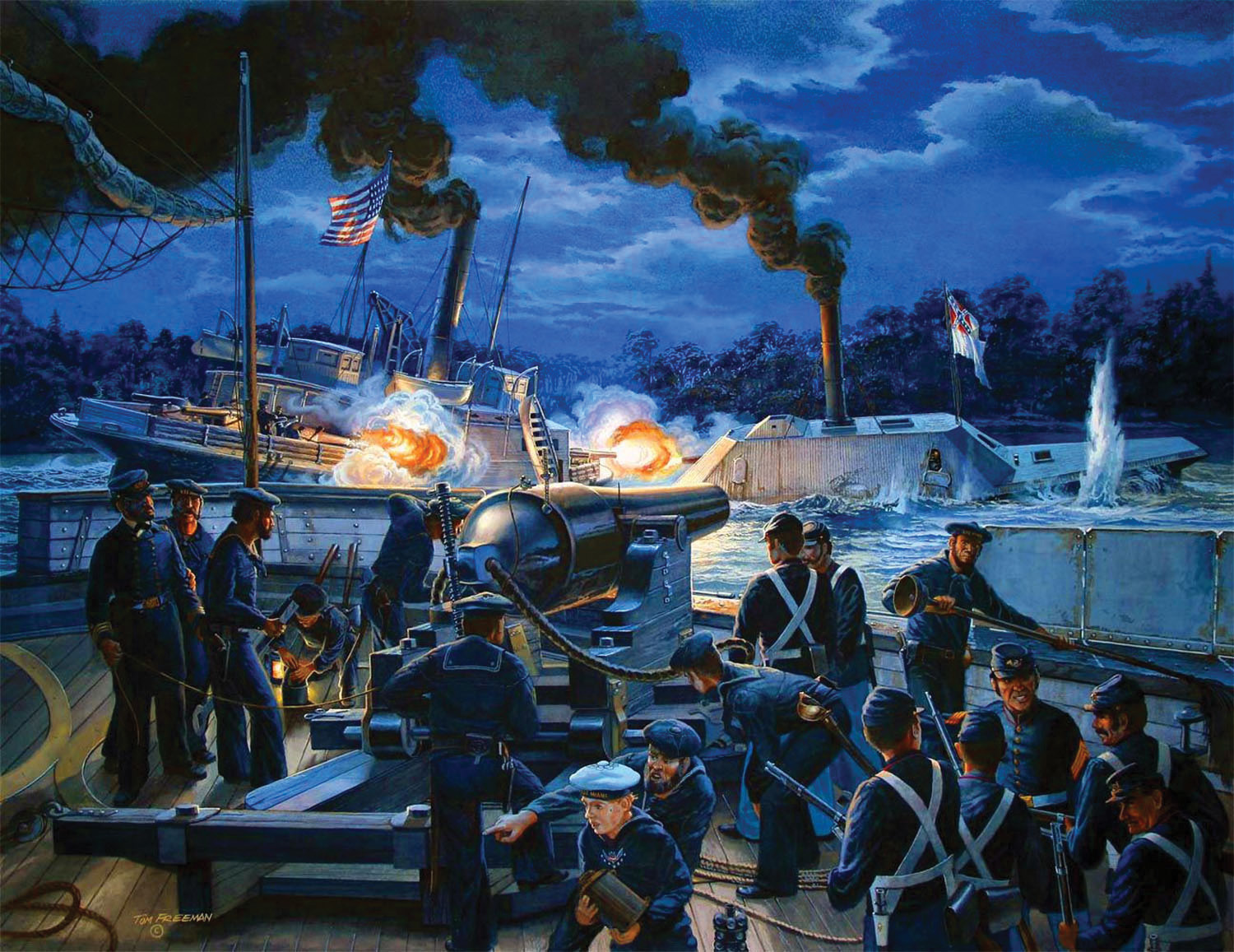

Flusser’s two largest steamers, the USS Southfield and the USS Miami, confronted the oncoming ironclad. At that point, the Roanoke River was about 500 feet wide. The Union gunboats, each about 200 feet long, were linked together with spars and chains. Flusser’s flotilla carried 11 nine-inch Dahlgren guns, a pair of 100-pounder rifles, and a large array of 20-pounder Parrotts and howitzers. If they could clamp the Albemarle between the two largest gunboats, their combined batteries might score decisive hits through the enemy gun ports, or even crack the Rebel ship’s armor.

Cooke charged directly at the enemy. The Albemarle rammed the Southfield, crushing the hull and piercing the boiler of the converted New York City ferryboat. Water rushed into the doomed Southfield, but the bow of the Albemarle remained trapped. The sinking gunboat threatened to pull the Albemarle down as well, but the Southfield lodged on the river bottom and rolled over, releasing the Confederate vessel.

Flusser personally fired the Miami’s big guns until a 100-pounder shell bounced off the armor plating. The shell hurtled back toward the Miami and burst, killing Flusser in the explosion. After the blast, the damaged Miami and other gunboats slipped away.

Shorn of naval cover, and with the Brooke rifles of the Albemarle turned against them, the garrison surrendered on the morning of April 20. The Confederates captured 2,500 prisoners and a great haul of heavy guns and supplies. The capture of Plymouth was the South’s greatest victory in North Carolina. Union commanders in North Carolina reeled with shock. Twenty-five miles southwest of Plymouth, the Union garrison abandoned the town of Washington and fled to safety at New Bern. Panic and looting resulted in fires that destroyed much of Washington.

Hoping to build on their success, Hoke and Cooke planned for the Albemarle to aid a Confederate attack on Union-held New Bern. The fuel tender Bombshell and the river steamer Cotton Plant, which was towing troop boats, followed the armored gunboat when the force steamed from the Roanoke into the Albemarle Sound on May 5, 1864.

Just off Sandy Point a few miles east of the mouth of the Roanoke waited eight Union gunboats: the Mattabesett, Sassacus, Miami, Ceres, Commodore Hull, Wyalusing, Whitehead, and Isaac N. Seymour, under the command of Captain Melancton Smith. Although Smith had only wooden gunboats, his vessels had about 60 heavy guns deal with this “second Merrimac” that rapidly closed with them.

Cooke opened the battle late in the afternoon. His guns cut up the rigging, wrecked the launch, and wounded six men aboard Smith’s steamer, the Mattabesett. Next, Cooke tried to ram the Mattabesett, but her captain avoided the collision.

Lieutenant Commander Francis A. Roe of the Sassacus saw that the Albemarle, after attacking the Mattabesett, was broadside to his steamer and only 400 yards away. Roe ordered, “Crowd waste and oil in the fires…. Give her all the steam she can carry!” Acting Master Charles A. Boutelle steered for “the junction of the casemate and the hull.” Surgeon Edgar Holden felt that the Sassacus “sprang forward like a living thing” until “came the order, ‘All hands lie down!’ and with a crash that shook the ship like an earthquake, we struck full and square.”

Boutelle landed the bow right where the aft end of the Albemarle’s casemate met the deck. Cooke’s men were thrown off their feet by the impact, which shoved the ironclad sideways to port. Both ships remained underway, locked together, with the side-wheel paddles of the Sassacus splashing as the engines drove them at full speed. Under the weight of the Union steamer and the force of her engines, the Albemarle’s after deck was pushed under the surface. “Stand to your guns, and if we must sink let us go down like brave men,” shouted Cooke as water rushed in through the aft ports.

Roe’s men threw grenades at the Albemarle’s hatches and tried to lob bags of gunpowder down into the smokestack. At point-blank range, Rebel guns fired into the Sassacus. One shot punched through its the starboard boiler, slashing steam pipes and machinery. “Steam filled every portion of the ship, from the hurricane deck to the fire-rooms, killing some, stifling some, and rendering all movement for a time impossible,” recalled Roe. So many tons of water poured from the boiler that the Sassacus suddenly keeled to port and broke away from the Albemarle.

From the Wyalusing, nothing was seen of the Sassacus but a cloud of smoke and steam, and it appeared the gunboat had sunk. Indeed, Roe thought the situation so dire he threw his signal books overboard to prevent their capture. After some anxious moments, flashes of cannon fire stabbed through the clouds, revealing to the Union fleet that the Sassacus was afloat and some of her gunners had returned to their posts. “The maintenance of the fight with their guns after the frightful disaster of the boiler was worthy of the proudest day of our naval history,” said Roe. Unable to make any headway, the Sassacus floated downstream, her guns blasting the Albemarle until she finally drifted out of range.

Captain Smith’s flotilla had other stratagems ready. The Mattabesett and the Commodore Hull dropped a large fishing net in front of the enemy gunboat. Their captains hoped to entangle the Albemarle’s propellers and rudder, but the net had no effect on their armored adversary. The Miami attempted to run close to Cooke’s vessel with a torpedo fixed on the end of a long spar, but the device would not detonate.

By 7:30 pm, Smith’s combined fleet had inflicted considerable damage to the Albemarle. An enemy shot broke off the muzzle of the aft Brooke rifle, leaving only one serviceable gun. Her funnel was torn by shot and was unable to provide sufficient draft for the fires. Additionally, Cooke was out of coal.

The the Albemarle’s fireboxes flared anew, as the Rebel stokers threw in the ship’s supplies of bacon, lard, and butter. Steam pressure climbed enough the get the vessel underway, and Cooke set a course back toward Plymouth. The battered Union flotilla did not attempt to pursue, but they had at least stopped the Confederate Navy from pushing farther into Union waters.

In the Battles of Plymouth and the Albemarle Sound, the fire from several dozen heavy guns did not hurt a single Rebel sailor in either action. Elliott wrote that only one sailor aboard the Albemarle was killed during the two battles: a sailor who peeked out of a porthole at the Miami was shot dead by a pistol bullet.

After the Battle of the Albemarle Sound, the ironclad remained tied up at Plymouth. General Robert E. Lee urgently needed Hoke’s troops to defend the Rapidan line at the outset of the Wilderness Campaign in the spring of 1864. Cooke was promoted to command the inland waters of North Carolina. Lieutenant Alexander F. Warley took over for him at Plymouth.

Warley worried over the vulnerability of his command, and he pleaded with local Army officers for extra guards to keep watch for Union moves. There was some cooperation. A few soldiers were stationed here and there downstream from Plymouth to keep an eye on the river. And a major outpost was established on a schooner anchored next to the wreck of the Southfield. According to Warley, aboard the schooner were an Army lieutenant and 25 soldiers with a field piece and a supply of signal rockets. But the protection was not as secure as it seemed. One of Warley’s petty officers later complained that the Southfield pickets had more than once been found sleeping.

As long as she remained afloat, the Rebel ironclad and her guns remained a dire threat to Union control of eastern North Carolina. To find a way to destroy the Albemarle, Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee turned to Lieutenant Cushing. The young lieutenant had made a name for himself with two bold forays to gather intelligence on the Cape Fear River around Wilmington. Cushing proposed two ideas. Lee rejected a plan to bring 100 men to the swamps across the Roanoke from Plymouth, launch inflatable rubber boats, and storm the Albemarle. Instead, he authorized Cushing’s second plan: a swift attack by two steam launches. Armed with boat howitzers and spar torpedoes, the launches would rush the Albemarle and detonate their charges against the unarmored wooden hull.

One of the steam launches was captured on its way to the Albemarle Sound, but the mission went ahead with the remaining 30-foot launch, known simply as Picket Boat No. 1. Cushing headed up the Roanoke with 25 men on the rainy night of October 27-28, 1864. His force included a party towed behind in a small cutter; these men were to prevent the guards aboard the Southfield from firing any signal rockets.

Aboard the Albemarle, Master’s Mate Lorenzo D. Pitt was officer of the deck. Lieutenant Warley had doubled the watch aboard the ironclad that night from three to six men. Most of the 60-man crew slept on board, and the rest bedded down nearby on the wharf.

A mile and a half downstream from Plymouth, Cushing passed unseen by any Army pickets on the bank. Ahead was the hulk of the Southfield, with the guard schooner tied next to it. Cushing passed within 30 yards of the schooner, but no one challenged them. Half a mile or so ahead lay the Albemarle at her moorings. They cast off the cutter to capture the guards on the Southfield.

The first warning the Rebels had was the sound of a barking dog. Awakened by the dog, a sleepy picket fired his musket. Pitt said he hailed from the deck of the Albemarle after spotting the boat 200-300 yards upriver. Receiving no answer, Pitt sprang the alarm rattle. His watchmen opened fire with half a dozen muskets. Awakened by the gunshots, Warley’s crew rushed to their battle stations.

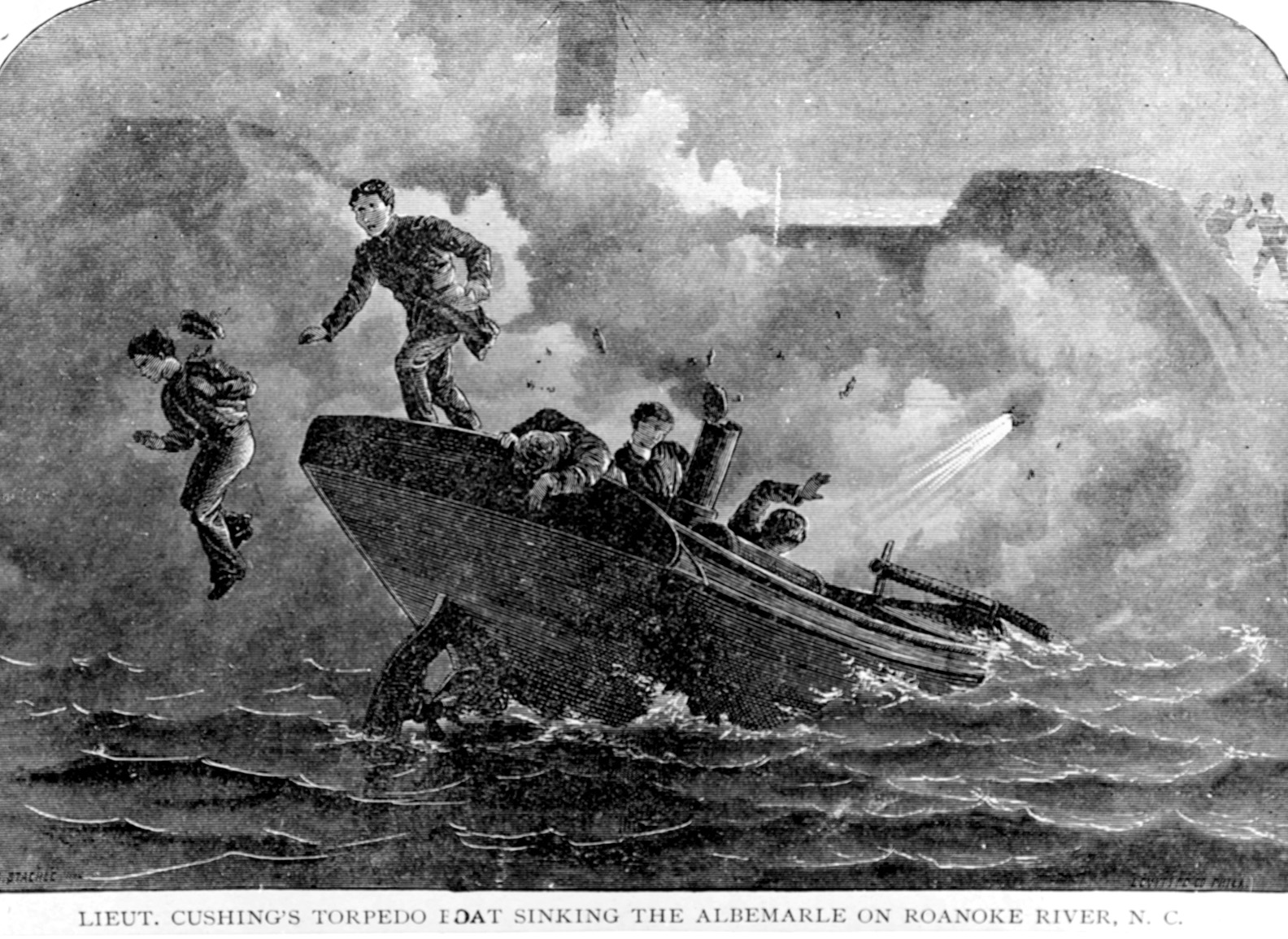

On the shore, soldiers lit a prepared bonfire. The flaring light revealed to Cushing something that he had feared: a log boom on the water that fenced in the gunboat. There was nothing to do but hope the logs were slimy with long exposure to the river water. Picket Boat No. 1 turned away in a circular path to gather as much speed as possible, then steered full steam ahead. Just after Cushing fired a blast of canister from the boat howitzer, the little engine generated enough momentum to jump the launch over the slippery log barrier.

Scarcely 10 feet from the muzzle of a Brooke rifle aboard the Albemarle, the raiders could hear the commands as the gunners readied the big cannon. Bullets nicked Cushing’s jacket as he used both hands to lower the torpedo. First pulling the right line to release the device, he tugged the left cord to detonate the powder. At the same instant the Rebels’ Brooke rifle fired a blast of grapeshot over the heads of the raiders, the Yankee torpedo exploded.

As water thrown outward by the blast rushed over them, Cushing ordered his crew to abandon the launch. Musket balls splashed into the cold river as the Union sailors tried to swim downstream. Safety was with the nearest U.S. gunboat, which was 12 miles away.

Warley sent his carpenter below to check the damage. He quickly returned and told the captain there was “a hole in her bottom big enough to drive a wagon through.” Working the ship’s pumps and a donkey engine did nothing to prevent the keel from settling into the mud and sand of the Roanoke, with only part of the casemate remaining above the surface.

After hiding at the edge of Plymouth, Cushing stole a skiff the next afternoon. For hours that night, he rowed toward a light in the distance. It was the USS Valley City, which did not pick him up for some time. Everyone on board believed Cushing had died in the blast that sank the Albemarle, and the Yankee tars thought the little boat contained a Rebel saboteur with an explosive device. Of the steam launch crew, one other man escaped, two drowned, and the rest were rounded up by the Rebels. The cutter’s crew took four Confederate prisoners off the Southfield and returned to the fleet.

Shorn of naval protection, Plymouth fell to a Union force on October 31. For the remainder of the war, Union control of eastern North Carolina was assured.

Cushing and his crew were voted the thanks of Congress. A prize court awarded the raiders $77,298.70 for the destruction of the vessel. Seven surviving enlisted men were awarded the Medal of Honor. Cushing, like the other officers on the mission, was ineligible. Even the commander of the Albemarle, Lieutenant Warley, acknowledged of the daring raid, “A more gallant thing was not done during the war.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments