By Pat McTaggart

The smell of victory was in the air as the forces of Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center continued to drive deep into the Ukraine during the final week of June 1941. To most of the young soldiers of the army group it seemed that this would be another unstoppable blitzkrieg. Their commander, however, saw things differently.

Von Bock was one of several higher commanders who were against the entire notion of invading the Soviet Union. His contemporaries described him as vain, irritating, cold, and humorless. On the occasion of his 60th birthday in December 1940, von Bock had a personal visit from Hitler. He bluntly told the Führer that he was concerned about the Russian undertaking, citing the lack of knowledge about the strength of the Red Army and the vast area that the Wehrmacht would have to fight in. Hitler met the comment with silence. Nevertheless, von Bock became commander of the most powerful of the three army groups poised to invade the Soviet Union.

At 0315 on June 22, 1941, the early morning silence was shattered by a thunderous barrage. The western sky lit up as thousands of German shells streaked overhead to hit identified Soviet targets. Operation Barbarossa had begun.

The German attack caused unbelievable panic at General Dmitrii Grigorevich Pavlov’s soon to be Western Front headquarters. Overhead, the Luftwaffe decimated the Red Air Force in Pavlov’s sector of the front on the first day, and the communications between Pavlov and his subordinate units were utterly disrupted, resulting in an almost complete lapse in command and control.

Soviet counterattacks during the first two days of the invasion were easily brushed aside. On June 24, Pavlov ordered his deputy, Lt. Gen. Ivan Vasilevich Boldin, to counterattack with the 6th and 11th Mechanized Corps, supported by the 6th Cavalry Corps, to stop the growing threat of a German encirclement of Soviet forces around Bialystok.

The attack was doomed from the start. Mechanical breakdowns plagued the Soviet tanks, and the Luftwaffe’s total control of the air proved disastrous for the Russian columns trying to move to their assembly areas. General Wolfram von Richtofen’s VIII Air Corps caused massive casualties even before the counterattack got started.

Among von Richtofen’s units was Lt. Col. Günther Freiherr von Maltzahn’s Jagdgeschwa-der (Fighter Wing) 53. Hermann Neuhoff, a pilot in Captain Wolf-Dietrich Wilcke’s III Group, described the scene: “We found the main roads in the area congested with Russian vehicles of all kinds, but no fighter opposition and very little flak. We made one firing pass after another and caused terrible destruction on the ground. Literally everything was ablaze by the time we turned for home.”

The commander of the 6th Mechanized, Maj. Gen. Mikhail Gregorevich Khatskilevich, was killed on the 24th. Of the more than 1,200 tanks in his command, approximately 200 made it to their assembly area. Low on fuel, the survivors were easy marks for the Germans.

June 25 saw more disaster for the Russians. A mere 243 tanks from Maj. Gen. Dmitrii Karpovich Mostovenko’s 11th Mechanized Corps made it to the front. Most of those were destroyed the same day while making piecemeal attacks on German forces. The accompanying 6th Cavalry Corps suffered more than 50 percent casualties, and its commander, Maj. Gen. Ivan Semeiotic Nikitin, was captured and later executed by the Germans.

On June 27, the 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups linked up near Minsk, trapping the Soviet 3rd and 10th Armies in the Bialystock area. Most of the 13th Army and part of the 4th Army were also inside the pocket. While German armored and infantry units fought to destroy the encircled Russians, other panzer forces continued to drive east. Bobruysk fell to General Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg’s XXIV (motorized) Army Corps on June 30, securing a crossing over the Berezina River. The battle for the frontier was basically over by July 3 with the elimination of the Russians inside the Bialystock pocket.

In Moscow, Premier Josef Stalin was furious. He had Pavlov relieved and arrested. The unlucky front commander was executed on July 22. Lt. Gen. Andrei Ivanovich Eremenko took over command of the Western Front until the new commander, Marshal Semen Konstantinovich Timoshenko, arrived in Smolensk on July 2.

Timoshenko’s main objective was to stop the German panzers at the Dnieper River. The odds of that happening looked pretty slim. Upon his arrival in Smolensk, Timoshenko found the front command in total disarray. His armored forces had been decimated, leaving him with about 200 tanks. About 400 aircraft were still operational, but they were being hunted down by the Luftwaffe and were largely ineffective.

Nevertheless, Timoshenko ordered his subordinates to make an orderly withdrawal to the river while using combat groups to strike at enemy spearheads. On July 5, the XXIV Panzer Corps reached the western bank of the Dneiper. Von Schweppenburg met heavy opposition from the remnants of Lt. Gen. Fedor Nikitich Rezmezov’s 13th Army that had escaped the Bialystock pocket. General Adolf Kuntzen’s XXXIX (motorized) Corps ran into the same thing as it confronted Lt. Gen. Pavel Alekseevich Kurochkin’s retreating 20th Army. Throughout the next few days, the Germans continued their advance at a moderate rate despite several intense counterattacks from the Russians.

By July 9, another major battle of encirclement ended as the Minsk pocket was crushed. The defeat cost the Western Front 290,000 prisoners and as many as 100,000 dead. Timoshenko was able to make good some of those losses as Stavka (the Soviet High Command) continued to pump reinforcements into the area.

The next week saw more German advances. Von Schweppenburg’s corps gained a bridgehead across the Dneiper on July 10. More German units expanded the bridgehead the next day, forcing the 13th Army to retreat once again. As the Soviets retreated the inexperienced conscripts that were arriving made fruitless counterattacks to try and stem the German advance.

summer of 1941. During those long days, the Red Army won its first major victory of the “Great Patriotic War” around Yelnya.

Another great battle of encirclement ensued, this time around Smolensk. General Heinz Guderian’s Panzer Group 2 struck across the Dneiper, and by July 13 his 29th (motorized) Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Walter von Boltenstern, was within 18 kilometers of the city. Meanwhile, General Hermann Hoth’s Panzer Group 3 attacked on a parallel course. By July 18, the two panzer groups were within 18 kilometers of each other, but strong Soviet counterattacks kept a gap open, allowing some Russian forces to escape.

At the head of Guderian’s spearhead was Brig. Gen. Ferdinand Schaal’s 10th Panzer Division. Guderian order Schaal to head toward Yelnya, a town of about 15,000 located on the banks of the Desna River 82 kilometers southeast of Smolensk. With an eye toward the future, Guderian saw the heights surrounding the town as the perfect spot for the continuation of the drive toward Moscow after the Smolensk pocket was eliminated.

Schaal moved out during the early hours of July 18. Upon reaching the Khmara River his lead elements found that the bridge crossing the river had been damaged by the Russians. At 0545 a single panzer from Lt. Col. Theodor Keyser’s 7th Panzer Regiment tried to cross the bridge but ended up crashing through it. Schaal was forced to postpone his advance until the following day so that the bridge and another one a few kilometers away could be repaired.

Yelnya, which means spruce grove, was defended by Maj. Gen. Iakov Georgievich Kotelnikov’s 19th Rifle Division of Maj. Gen. Konstantin Ivanovich Rakutin’s 24th Army. Upon hearing of the enemy’s approach, Kotelnikov used the time lost by 10th Panzer to good purpose. An antitank ditch that engineers had dug across the road to Yelnya was fortified, and some heavy artillery was allotted to bombard the road once the Germans attacked.

The Duna River, which began on the Smolensk Heights northest of the town, was about 60 meters wide and three meters deep in the area. Kotelnikov ordered that the eastern bank be fortified and had service troops and civilians begin digging trenches and creating strongpoints on the heights east of the town.

To Schall’s left, SS Maj. Gen. Paul Hausser’s 2nd SS (motorized) Division “Reich” was ordered to advance to Dorogobuzh, some 40 kilometers north of Yelnya, and capture the heights in that area. SS Major Otto Kumm, commander of the division’s “Der Führer” (DF) Regiment, was to lead the assault. Kumm had his doubts about the mission. An overcast sky with intermittent showers prevented him from having hard air reconnaissance on enemy dispositions. Nevertheless, Kumm started out on his 100-kilometer march with SS Captain Johannes Mühlenkamp’s reconnaissance battalion in the lead.

“The road conditions were very bad,” Mühlenkamp recalled. “Bridges that crossed small streams in the area were worthless. The Ivans were dug in west of Dorogobuzh, and we launched an attack in the area to drive them out. However, [enemy] reinforcements arrived and counterattacked, forcing us to retreat. The fighting continued throughout the day [July 19].”

In the Yelnya sector, 10th Panzer came under artillery fire as it neared the enemy antitank ditch, which stretched about two kilometers on either side the of the Yelnya road. The Russians were dug in and refused to budge, so Schall split his spearhead into two combat groups to outflank the enemy. Lt. Col. Karl Mauss led the left group, consisting of the II/Panzer Regiment 7, II/Rifle Regiment (motorized) 69, and the 3/Anti-Tank Detachment 90. On the right Lt. Col. Keyser had the I/Panzer. Regiment 7 and Motorcycle Battalion 10.

While other elements of the 10th kept the Russians manning the ditch busy, the two combat groups made their way around the enemy position. The Soviets, realizing their position was flanked, retreated while taking many casualties. Lead elements of 10th Panzer entered Yelnya around 1430 and soon found themselves heavily engaged with two of Kotelnikov’s regiments. The fighting was savage, with the Germans having to clear each house individually.

As his men fought to take Yelnya, Schaal received an order from General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, commanding the XLVI Panzer Corps, to send a combat group to the Dorogobuzh sector to support the Reich Division, which had also run into fierce resistance. Schall protested, stating that he was embroiled in combat at Yelnya and weakening his division would only prolong the matter, but von Vietinghoff would have none of it. The I/Rifle Regiment (motorized) 69 with Artillery Regiment 90’s 4th Battery and a tank destroyer unit were detached to help the SS.

Kotelnikov’s men were fighting to the death. The dismounted Motorcycle Battalion 10 had taken heavy casualties, but it had cleared the eastern half of Yelnya by 1800. Schaal committed his II/Rifle Regiment (motorized) 69 to support the motorcyclists and sent the 86th Rifle Regiment (motorized) to form a defensive line northwest of the town.

As the infantry moved into the western part of the town, they came up against strong Russian positions along a railway embankment west of the Yelnya train station. At 1825 the Soviets launched a strong counterattack. With Red Army artillery pounding the German line, the situation was confused for a while, and Schaal was heard to comment, “It is questionable whether we can take and hold Yelnya.”

The Soviet attack lasted nearly four hours, but the Germans were able to hold on. Supported by panzers from Panzer Regiment 7, the infantry cracked the rail embankment defenses and pushed the depleted Russian forces back. By 2300 the entire town was in German hands. Both sides had had enough for the day, and the weary troops settled in with dead and wounded littering the town. The II/Rifle Regiment (motorized) 69 lost a total of 60 men during the fighting, and losses in the motorcycle battalion had also been high.

In the Dorogobuzh sector, Hausser’s Reich was not as successful. Although the Russians lost five airfields in the area, which would benefit the Luftwaffe later on, the Reich’s advance was slowed to a crawl. Taking advantage of low cloud cover, the Red Air Force launched several bombing attacks that wreaked havoc on the division’s spearheads. Soviet counterattacks further hampered the division’s advance. “Division dispersed over a great area—enemy everywhere,” Hausser wrote in his personal notes.

July 19 was the first day of what would become weeks of horror in the Yelnya salient. The German blitzkrieg would mean nothing, and veterans of World War I stated that the fighting there was a throwback to the bloody trench battles of that war. Neither side recognized that on the first day, but the men that fought there would soon find themselves inside a living nightmare.

July 20 found Schaal’s division stalled in front of dense enemy positions on the hills west, north, and south of Yelnya. His mechanized vehicles were in trouble—literally out of oil. The lightning advance through Belarus had taken its toll on the vehicles’ engines as they raced along the dusty roads that were the primary supply and communications routes. The dust destroyed air filters, and the engines were using twice as much oil as normal. Breakdowns and the lack of oil virtually immobilized the division.

With the 86th Rifle Regiment protecting the northern flank of the salient and the combat group sent to help the Reich still absent, the remaining units of the 69th Regiment did not have the strength to overcome the Russian defenses. Soviet artillery units were in well camouflaged reinforced positions a good way behind the line and peppered the area, and Russian reinforcements were on the way to replace the dead and wounded.

To Schaal’s north, Hausser’s Reich was still having problems. His Deutschland Regiment tried to make headway west of the previously captured airfields, but Soviet defenses were strong. With heavy enemy artillery fire stalling the attack, Soviet forces were pushing around the division’s flanks. Brig. Gen. Wilhelm-Hunold von Stockhausen’s Infantry Regiment (motorized) “Grossdeutschland” (GD) had arrived to take over from Reich security forces guarding the airfields, freeing them up for use at the front, but even with those added troops Hausser was hard pressed to hold his division’s positions.

Von Vietinghoff, worried that his corps might be split in two, discussed the situation with Guderian. When the two were finished, it was decided that the Dorogobuzh mission had to be secondary to clearing the Yelnya bend. Therefore, Hausser was ordered to disengage and head south to occupy the northern flank of the Yelnya salient, releasing the 86th Infantry Regiment.

With the Reich pulling out, the positions west of the airfields were also occupied by the GD. An account in the divisional history describes the first perceptions of the new positions: “The fields are fallow, the villages gloomy. The landscape is wide, gray, and ugly, the sky appears larger than at home. In the terrain in front of us flows a small brook. Over in the direction of the enemy lay a series of interconnected woods.”

Red Army artillery gave the GD a warm welcome. Heavy fire of all calibers raked the area as the men dug in. A member of the unit described the barrage: “Most of the men are sitting in a slit trench. It is narrow and deep. While under artillery fire there are only three possibilities; either one is not hit at all, or one is temporarily buried, or there is a direct hit. Then it’s all over in any case. In artillery fire one must remain in one place. Many have died while searching for another place.”

After the initial bombardment an uneasy peace fell upon the area. The regiment used the time to strengthen its positions knowing that the lull would not last long. Reconnaissance patrols were already reporting the sounds of motorized equipment in the distance. It was clear that the Soviets were bringing reinforcements to the front and that a new attack would soon take place.

While the forces at Yelnya continued to slug it out, Timoshenko was in Moscow. In a series of meetings with Stalin and Red Army Chief of Staff General Georgii Konstantinovich Zhukov, the three men discussed the possibility of an offensive in the Yelnya area aimed at blunting any enemy thrust on Moscow. Before Timoshenko returned to his headquarters on the 21st, plans had been worked out and reinforcements were underway for the operation.

As Timoshenko was returning, the Germans were planning an attack of their own with the combined force of the Reich and 10th Panzer, augmented by assault guns. Rakutin’s 24th Army was ready. New units were already arriving for the impending Soviet assault, and positions on the heights around the Yelnya salient had been further strengthened with additional heavy artillery.

German reconnaissance had noticed the movement of new enemy troops, and von Vietinghoff’s orders for his own attack were short and to the point. “Enemy defending in fortified positions in the Desna-Usha sector east of Yelnya. Enemy reinforcements approaching Yelnya from the south and southeast.

“The XLVI Panzer Corps will attack south, possibly southeast of Yelnya before noon on 22 July with the 10th Panzer Division on the right and the SS Division Reich on the left.

“Objective: Destroy newly arrived enemy forces and capture ground easily defended by minuscule forces.”

Schaal’s 10th Panzer objectives were to break through the Russian positions south of Yelnya and roll up the entire Desna defense position in the sector.

Deploying in an area northeast of Yelnya, Hausser’s Reich would attack Pronino and Hill 125.6, some eight kilometers east of Yelnya. Once that was accomplished the division was to attack and secure the heights around Kostyuki, eight kilometers southeast of Pronino.

At 1445 the artillery of 10th Panzer opened up a murderous fire on the entrenched enemy. The targeting was helped by two aircraft from the divisional reconnaissance squadron. The other aircraft of the squadron were grounded due either to the lack of fuel or mechanical difficulties.

As the final rounds struck the first line of Russian positions, the infantry attacked across a road embankment and headed for the Soviet defenses. The Red Army soldiers met the attack with heavy fire. Individual positions held out to the last and had to be taken in hand-to-hand combat. A bunker line was secured as Rifle Regiments 69 and 86 reached their first objectives, but several Soviet positions still held out while the first wave of Germans passed them by.

Colonel Wolfgang Fischer, commander of Rifle Brigade 10, was forced to halt his regiments north of the village of Lipnaya, about 10 kilometers south of Yelnya, due to nightfall. Without the benefit of reconnaissance aircraft, his infantry would be groping in the darkness in the midst of strong enemy defenses. The clearing of the Desna positions would have to wait another day.

As evening fell, the few serviceable tanks of Panzer Regiment 7 were withdrawn to an area 12 kilometers west of Yelnya. Mechanics were working around the clock to repair the overused vehicles, but parts were still practically nonexistent. At the end of the day, the division had only five Panzer IIs and four Panzer IIIs fit for combat. Exactly one month before, as the division began its drive into Russia, the complement was 45 Panzer IIs, 105 Panzer IIIs, and 20 Panzer IVs.

The attack began earliern Schaal’s left flank. Because of ammunition shortages, there was no preliminary artillery barrage. The I and II Battalions of SS Colonel Wilhelm Bittrich’s “Deutschland” (“D”) Regiment were the first to advance. Soviet units opened fire from their entrenched positions on the heights, causing heavy casualties. The battalions halted to regroup and struck out again, only to be driven to ground.

Arnold Hoffmann, a member of I/“D”, described the attack: “The 3rd [company], the spearhead company, suffered heavy losses. All the 1st Platoon squad leaders died. The company had to dig in…. We dug in next to the 1st [company] command post. Several officers had dug in directly at the embankment, near the I/“D” command post. They had carbines in their hands and were prepared to defend against attacks together with their men.”

The Soviets did indeed counterattack, hoping to drive the SS infantry back. Russian artillery crashed into the German positions as the attack began. Overhead, the Luftwaffe tried to identify the enemy battery positions, and several guns were destroyed, but most of the masterfully camouflaged positions escaped detection.

Hoffmann recalled a particular part of the action as the Russians closed with the Germans: “I can still see my friend, SS Private Paul Holzapfel from the 3rd Company’s 3rd Platoon, standing next to a Russian antitank gun without sights, peering over the gun tube and firing at the attacking Russians….”

Meanwhile, Kumm’s DF Regiment had moved forward. The combined force of the two regiments kept the Russian counterattacks at bay, and the division was able to push forward to engage the strong enemy positions on the heights. Men on both sides fought and died in the burning heat of the afternoon while artillery rained down on friend and foe alike.

Finally, Kumm sent SS Captain Hahn’s III/DF to assault the Russians’ left flank. After a bitter fight the flank was finally turned, forcing the Soviets to retreat. Around 2100 the exhausted men of the Reich took control of Hill 125.6. They could go no farther.

It had been a costly fight for both sides, and neither the Germans nor the Russians seemed to have the will to continue. As the men lay in their positions, only occasional artillery fire and the cries of the wounded pierced the silence of the night.

The Soviet units holding the heights around the Yelnya salient had suffered heavy casualties, especially among the regiments of Kotelnikov’s 19th Rifle Division. However, Rakutin was funneling more and more replacements and reinforcements into the area to make good those losses. Maj. Gen. Ivan Nikitch Russiianov’s 100th Rifle Division and the 103rd Rifle Division moved to take positions on the 19th’s right flank, taking some of the pressure off Kotelnikov’s men. Other units moved in on the left flank of the division. New artillery units were also placed behind the line. Included in those units were Katyusha rocket launchers, which would provide a very unpleasant surprise for the Germans.

On July 23 at 0400, the Russians attacked all along the front of the “D” Regiment’s line. By 0600 the entire front of the Reich Division was under heavy artillery fire and tank-supported infantry attacks. It was clear that the Soviets were aiming to regain the high ground lost on the previous day.

Hidden by the dense grain fields in the area, the Russians were able to close with the Germans. In the scorching heat, they advanced on the heels of their artillery, but they were met with devastating defensive fire from the SS infantry and heavy weapons companies. The fire proved too much for the Russians, and they retreated in disorder.

Soviet forces also hit 10th Panzer. Most of the Russian units were on the division’s south and southwestern flank, and it was there that the attacks were heaviest. Luckily, the division had the added firepower of the 817th Mortar Detachment and Cannon Detachment 268, which were corps units. Combined with the divisional artillery of the 10th, the Russians were kept at bay while suffering heavy losses.

The division was forced to strengthen its left flank when it received a communication from Mühlenkamp’s Reconnaissance Battalion, which was occupying positions about 20 kilometers west of Yelnya near the Glinka Railroad Station. Mühlenkamp reported that he was under heavy artillery fire and infantry attack. If he was forced to retreat, it would threaten Schaal’s left. In response to the information, some artillery was shifted to help with Mühlenkamp’s defense. Losses piled up for the SS, but they managed to hold their position with the added support.

In the midst of the battle, Guderian showed up at Schaal’s headquarters. Schaal informed his superior about the attempt to expand the salient. At the same time, he told Guderian about the wretched shape that his tanks and vehicles were in. Oil, parts, fuel, and artillery ammunition were in short supply, and Schaal bluntly stated that it would most likely not be possible to make any great gains in the area without resupply. The speed of the initial German advance into Russia meant that supply columns would have to travel about 450 kilometers to reach Yelnya—a daunting task for any army at that time.

Guderian also visited the Reich Division and received a similar report. Guderian wanted to see the front for himself, so he visited the positions of SS Captain Fritz Klingenberg’s Motorcycle Infantry Battalion, which was the farthest unit occupying the eastern point of the salient. Klingenberg gave Guerin a no-nonsense junior officer’s view of the capabilities of his men. They had suffered many casualties, and they were tired from days of battle. They could fight, but the enemy positions facing them were just too strong to overcome without more supplies and more support.

Returning to his own headquarters, Guderian ordered von Vietinghoff to put his corps on the defensive until supplies could reach the front. He also ordered von Stockhausen’s GD to move into the Yelnya salient as soon as it could be relieved.

The arrival of the GD would be a welcome addition to the German forces defending the Yelnya area, but it would have to wait. The division scheduled to relieve von Stockhausen was still part of the forces trying to eliminate the Smolensk pocket. Heavy fighting was still going on, and the German lines were not strong enough to seal its perimeter.

Guderian steadfastly refused to yield his planned jumping off points for his future drive on Moscow, and in doing so the ring around the Russian troops at Smolensk remained porous. Historian Brian I. Fugate wrote: “It is true that the Wehrmacht was overburdened, but the Smolensk pocket could have been sealed effectively if Guderian had been willing to give up his position at Yelnya. In his eyes, however, forfeiting Yelnya would have been giving up Moscow, and that is something he would not do.”

At Smolensk the Russians threw everything they had against the German perimeter, but the attacks were poorly coordinated. Smolensk was a time-consuming operation for the Germans. The trap would finally be closed on July 27, sealing the fate of most of the 16th, 19th, and 20th Armies. More days of fighting lay ahead before the pocket was finally eliminated. An estimated 309,000 prisoners were taken, and thousands more soldiers lay dead on the battlefield, but many troops were able to escape through the thin German lines.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring estimated that more than 100,000 Red Army soldiers managed to escape the pocket. Returning to their own lines, they would be used to form new divisions that would continue the fight against the German invaders.

As it awaited relief, the GD was going through the same hellish fighting that was occurring at Yelnya. Well-entrenched Soviet artillery rained death on the German positions before each Russian attack. A member of I/GD described the opening of one such assault: “From 0100 to 0300 the fire was weaker. Then it thundered down with renewed vigor…. Right at the beginning they brought in my old Oberfeldwebel [sergeant] Herold; he had lost his hearing and his wide eyes stared into space.”

As the bombardment relented, the commentary continued: “They’re coming! Great masses of men were climbing down into the bottom land. Mounted officers circled round them. Everything ahead of us was brown with Russians…. A sustained fire opened up from 12 [German] machine guns at once…. The Russians came ever closer. Their fire sang, crackled, and whistled everywhere….”

That attack, like many others, was finally beaten back. Once the Russians retreated, the artillery renewed its bombardment. The cycle would repeat itself day after day until the GD was finally relieved.

At Yelnya the fighting continued unabated. The Russians made another attempt to take Hill 125.6 with a combined armor-infantry attack. With his own antitank guns damaged or destroyed, Kumm called on 10th Panzer for assistance. Schaal sent most of his Anti-Tank Detachment 90 to back up the SS.

Fighting raged throughout the morning and early afternoon as the Russians tried to press their numerical advantage in the sector. In response to another request, Schaal sent the few combat-ready panzers of 7/Panzer Regiment 7 to assist in the defense. Their timely arrival on the scene stopped a Russian penetration that had taken place a few minutes earlier. Well-placed shots from the panzers destroyed all seven of the Soviet tanks that had broken through.

In another sector, SS Sergeant Erich Rossner was defending a ravine with his 50mm antitank gun. A group of eight Russian tanks appeared, and Rossner ordered his gunner to wait until they came within 50 meters of his position before he opened fire. After the first tank in the column was destroyed, the second tank, equipped with a flamethrower, set off a jet of flame toward the German position. Rossner’s men jumped away just in time to avoid the flames.

As the crew of the tank dismounted to inspect the position, Rossner and his men opened fire, killing the curious Russians. They quickly returned to their gun and destroyed the seven remaining Russian tanks. The 23-year-old Rossner was wounded by shrapnel the following day and died on July 30. He was posthumously awarded the Knight’s Cross for his actions.

The Russians pressed their attack along the entire division’s front, with particularly heavy fighting taking place in the northeast sector. Soviet troops were able to move down the main road from Dorogobuzh quickly, making it easy to replace battle casualties and keep the attack going. A breakthrough there would threaten von Vietinghoff’s entire corps.

While the Soviets fired their artillery with impunity, the Reich artillery continued to be plagued with shortages. On July 24, the Russians managed to take the village of Uschavkova on the Dorogobuzh road about 38 kilometers northeast of Yelnya. The village changed hands three more times before the Germans finally regained it, but a Russian counterattack was able to cut off the defending troops.

On the 25th the Reich’s chief of staff, SS Lt. Col. Werner Ostendorff, arrived in the area with a depleted panzer company from the corps reserve. Carrying out a personal reconnaissance, Ostendorff placed his meager forces in the most advantageous avenue of attack and led them through the encircling Soviets, restoring the main line.

Other attacks hit the junction of the Reich and 10th Panzer. Schaal deployed some 88mm antiaircraft guns on the front line, and together with accurate fire from his few combat ready panzers they destroyed 13 of 27 Russian tanks threatening to break through.

The Russians still had not mastered the intricacy of a combined infantry-armored assault, which showed as the tanks outran the infantry and fell prey to German infantry. A German corps order of the day mentioned some of the actions that took place on the 25th.

“SS 2nd Lt. Weise and SS 2nd Lt. Ehm, who jumped onto heavy tanks, fought the crews through the vision ports and set the tanks on fire with explosives or gasoline when neither 37mm antitank guns nor heavy infantry guns could knock them out. The 11/“D”, under its company commander SS 1st Lt. Kumpf, independently counterattacked, inflicting bloody losses on the enemy. It destroyed three tanks, five antitank guns, two heavy mortars, six heavy machine guns, five light machine guns, and a large number of rifles.”

Captain Mühlenkamp recalled, “We had never experienced such fighting before. There was confusion everywhere, and the Russians fought to the death, as did our men. No quarter was asked or given.”

On July 26, a German patrol found the position of a depleted squad led by SS Sergeant Förster, which had defended the left flank of SS Captain Klempt’s 1st Motorcycle Infantry Company. Förster and his men, SS Privates Klaiber, Buschner, Oldenbuerhuis, Schwenk, and Schyma, were all dead. Around their position lay 60 to 70 dead Russian soldiers.

Guderian had told both Hausser and Schaal that infantry divisions would soon arrive to relieve their two divisions, and word soon spread to the frontline units. However, the elation of the troops faded as the fighting at Smolensk continued and Soviet attacks stepped up, looking for a weak place in the line.

At 1050 on July 26, another Russian attack hit the junction of the two divisions. Klingenberg’s motorcycle battalion was hit by different enemy forces at 1105, followed by another attack against Bittrich’s “D” and SS Colonel Jürger Wagner’s SS Infantry Regiment 11. The attacks were beaten off, but casualties were heavy. At 1345, Hausser sent the following message to von Vietinghoff:

“Artillery fire upon Regiment Der Führer becoming more unbearable. Wounded can no longer be brought to the rear. Decisive measures are necessary immediately. If not, the division is in danger of being pounded to pieces.”

It was a stark admission, especially for an SS division that had experienced nothing but victory during the war. Von Vietinghoff could offer nothing. The much needed fuel and artillery ammunition were still making their way to the front, and the Luftwaffe was dealing with Red Air Force units that were bent on destroying their newly won airfields.

On the front line, both sides had constructed a maze of slit trenches, foxholes, and bunkers to protect themselves from enemy artillery and air attacks. “When I was young I talked to veterans from World War I who had served on the Western Front,” Mühlenkamp recalled. “They described the positional warfare and life in the trenches, but I could not fathom what they had really experienced. At Yelnya I found out what they had gone through, although our ordeal lasted only a few weeks, not years, thank God.”

July 27 brought another hope of relief for the men of the 10th Panzer and Reich Divisions. The Smolensk battle was finally showing signs of success, and Guderian thought, rightly or wrongly, that some of the German units manning the pocket perimeter could start moving toward Yelnya.

Brigadier General Erich Straube, commander of the 268th Infantry Division, radioed von Vietinghoff to discuss the movement of his division. He suggested that von Vietinghoff send all his available corps vehicles to transport as much of his infantry as possible to the pocket. In the end, Straube was able to pack two regiments into the vehicles and send them toward Yelnya, saving at least one or two days of forced marching. Straube’s third regiment, along with the horse-drawn elements of his division, would make their way on foot.

Elements of Maj. Gen. Friedrich Bergmann’s 137th were also moving to relieve von Stockhausen’s GD. By July 28 the III/GD was able to disengage and move into the salient, where it was held as a reserve unit. The 41st and 85th Engineer Battalions, units attached to higher headquarters, were also moving into the Reich and 10th Panzer sectors. The new units came under fire immediately, even as elements of 10th Panzer and Reich strove to disengage and move back.

Relieving a friendly unit that is disengaging from the enemy is a hazardous maneuver at best, and the Russians took full advantage of the action. The new German units trying to move forward to occupy frontline positions were slowed by the enemy fire, while the SS and panzer troops in the front line came under more assaults. Estimates from the Reich’s intelligence officer placed five enemy rifle divisions and two mechanized regiments in front of the division’s lines.

Although elements of the 268th and the engineer battalions were able to man the line, the units being relieved were just shifted to other parts of their division’s front. Casualties had been so high that they could not afford to be rotated to the rear. An estimated 2,000 Russian infantry, supported by tanks, attacked Klingenberg’s battalion at 1630 on the 28th. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the motorcyclists repulsed the enemy, but Klingenberg’s men were worn out. At 1820 Kumm’s “D” came under heavy artillery fire, causing more casualties before a flight of Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers appeared to silence the enemy.

The 10th Panzer was also hit hard, even as Bergmann’s 499th Infantry Regiment was moving into the line. On the 29th the division’s operations officer, Major Görhardt, was on his way to brigade headquarters when the wagon he was riding on struck a mine. Gerhardt was horribly burned and was on his way to a hospital in Germany a day later. The division had lost a key member of its headquarters just when it needed him most.

With the Smolensk pocket finally destroyed, Guderian was ready to move on Moscow. The Yelnya salient was still a thorn in his side, but it had become a matter of prestige for it to be held. If he could not use Yelnya, he planned to move his panzer group north to find a new area for his planned offensive. The gradual relief of the troops in the salient would continue while the rest of the panzer group took time to refit as best it could.

More infantry units were finally able to begin moving toward Yelnya to occupy the salient. The infantry would be charged with holding and enlarging it. However, when Guderian was finally ready to move his panzer group he would take his attached army artillery units with him. The Luftwaffe units supporting the salient would also move with him. The move would leave just corps and divisional artillery units to continue to support the infantry.

Things were about to change on the Soviet side. General Zhukov was one of the few Soviet generals and politicians who had the nerve to stand up to Stalin. As early as June 29, he had sent the Soviet leader an analysis of the situation after one week of war. He pointed out the threats of encirclement for the Southwest and Central Fronts and advocated evacuating Kiev and retreating to defensive positions on the eastern bank of the Dneiper River.

Stalin was enraged when he read the report. Even as the events Zhukov predicted were unfolding, he summoned the general to his war room. When he entered the room, Zhukov found Stalin flanked by two of the most dangerous men in the Soviet Union: Lavrentii Pavlovich Beria, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), and Commissar Lev Zakharovich Meklis, the head of the Main Political Propaganda Directorate.

Zhukov recalled Stalin “cursing me in crude terms for suggesting that we lose Kiev which, like Leningrad, he counted on holding at all costs.” The general was not cowed as Stalin and his two companions glared at him.

“If you think the Chief of the General Staff talks nonsense, then I suggest you relieve me of my post and send me to the front,” he replied.

During the coming weeks Zhukov sent a steady stream of reports concerning the worsening conditions at the front. In one of them he drew attention to the Yelnya salient, which marked the easternmost advance of the German Army in Russia, and pointed out the necessity of destroying it to eliminate its threat to Moscow.

Remembering their previous turbulent meeting, on July 30 Stalin decided to name Zhukov as the commander of the Reserve Army. The army was formed to control the training of newly formed units. Located in the rear, the army’s divisions could be used as a reserve to counter any German penetrations on the front east of Yelnya. Zhukov sped up the combat training of his divisions so that he could use them—not defensively but offensively. Within a month the Germans inside the Yelnya salient would learn just what an effective commander Zhukov was.

Meanwhile, the battle that was Yelnya continued. At 0200 on July 30, a section of 10th Panzer’s line came under heavy artillery fire, followed by a mass infantry attack at 0345. The Russians hit the positions of the II/Rifle Regiment 86, II/Rifle Regiment 69, and the 10th Motorcycle Battalion. After intense fighting, the attack was beaten off.

As the sun rose, another massive bombardment hit the line at 0700. The positions of the motorcycle battalion were penetrated by a tank-infantry force, and the situation was quickly becoming critical. Schaal committed his last reserves, a company from Panzer Engineer Battalion 49, to the area. He also called the commander of Straube’s Artillery Regiment 268 and requested aid. The 268th sent two battalions forward and had artillery observers sent to the front line. With their help, the Soviets were forced to retreat, and the line was restored.

July 31 brought more carnage. In the GD sector the Russians used their Katyusha rockets for the first time. “There was little we could do, and nothing could prevent the enemy from placing his masses of artillery wherever he liked,” the divisional history states. “There were no pauses between impacts. We pressed close together in the semi-darkness of the slit trench … for the first time, the so-called “Stalin Organ,” which was a salvo of 36 rockets, was used. Its greatest effect lay in the large amount of shrapnel it spread horizontally over a wide area. The new weapon’s effect on morale was alarming.”

More of Straube’s 268th was arriving, but once again the relieved units were just shifted to other areas of the line. One of Straube’s regiments, which had just taken over a section of the Reich’s line, was promptly attacked by Russian infantry supported by tanks. In close combat, Straube’s men destroyed two tanks, two antitank guns, 12 heavy machine guns, and several light machine guns.

A Soviet officer and several enlisted men were also captured. The regiment had received its first taste of the Yelnya salient only an hour after it had arrived at the front. In its first battle it had lost 12 officers and 28 men killed and 52 men wounded.

The salient now extended along the Dneiper bend from Stradino, about 48 kilometers northwest of Yelnya, to Shmakovo, 30 kilometers south-southwest of the town. It was an extremely long front to cover. Battalions covered an average of 4-5 kilometers, whereas German military doctrine set a limit of two kilometers at the most.

An enemy attack on August 2 broke through a gap between the 41st Engineer Battalion and the 11/SS RGT 11. With artillery ammunition still almost nonexistent, the Russians were pushed back by a desperate counterattack that resulted in heavy casualties. A divisional report to von Vietinghoff emphasized the critical situation: “If the division [(Reich] must remain in this position for several more days, everything will be crushed. The present strength of an infantry company is 60-70 men. III/SS RGT 11 is holding a five-kilometer front with 11 officers, 32 NCOs, and 232 men. Engineer battalion only has six platoons remaining in the unit. Reserve presently consists of only parts of the reconnaissance and motorcycle battalions.”

After repelling another attack, this time aimed at the II/DF, the artillery unit supporting the battalion sent Hausser the following message: “The batteries must withdraw if no more ammunition arrives. Occupying positions without firing will cause unnecessarily large losses.”

The battle raged throughout the first week of August. The Soviet pressure on the salient grew steadily as new divisions were fed into the Russian line. Attacks on the northeast portion of the salient were successful in breaching the line in the GD sector. The regiment sent an ominous message to corps headquarters, stating: “Could not hold the positions reached this morning. Some companies only have 20 men remaining. Two officers have been killed in action. Cannot obtain reinforcements from the right flank. Enemy still making continuous tank attacks. It is questionable whether we will make it through the coming night.”

Von Vietinghoff responded by attaching the GD to the Reich. Counterattacks to restore the line failed, and the GD was forced to establish new positions farther south. The casualty tally continued to grow as the XLVI (motorized) Corps reported losses of 3,616 officers, NCOs, and men for the period of July 22 to August 3. Straube’s 268th, which had only been in the line for a short time, contributed 456 men to that total.

On August 5, Colonel Gustav-Adolf von Zangen, commander of Infantry Regiment 86 of Maj. Gen. Ernst-Eberhard Hell’s 15th Infantry Division, arrived at von Vietinghoff’s headquarters and received a detailed briefing on the situation inside the salient. His orders were to relieve the 11th SS Infantry Regiment as soon as possible. Meanwhile, corps transport units would be sent to bring up the 81st and 106th Regiments of the 15th to relieve the GD and form a corps reserve. Maj. Gen. Martin Dehmel’s 292nd Infantry Division was also scheduled to arrive within the next two or three days.

By August 6, some of the bloodied units at the front were turning their positions over to the arriving infantry. The 11th SS pulled out of the line as the 15th Infantry took its place. The 81st and 106th Infantry Regiments were due to move into the GD sector the following day, and vehicles from the Reich were sent to pick up Colonel Horst Christiani’s Infantry Regiment 508 from Dehmel’s 292nd.

By the end of August 10, most of the Reich and GD were finally out of the salient, assembling west of Yelnya, beyond the range of Soviet artillery. From July 20-August 9 the 10th Panzer, Reich, and GD had lost a total of 924 officers and men killed, 3,228 wounded (many of them seriously), and 100 missing.

“The men were happy to get out of the hell of Yelnya,” Mühlenkamp recalled. “We didn’t care where we were going. It was just a relief to get out alive.”

As the infantry units began manning the line, the defense of the salient passed temporarily to the control of General Friedrich Materna’s XX Army Corps, which would still be under the overall command of Guderian’s Panzer Group 2. Rakutin took advantage of the minor chaos caused by the change of command and the redistribution of troops to launch battalion- and regiment-sized attacks with his 24th Army at the junction of the 15th Infantry Division and the remaining elements of the Reich that were still in the line.

The Russians hit German positions on the heights near the village of Klematina, about 16 kilometers northeast of Yelnya. Pounded by the Red Air Force, which had been reinforced in the area, and artillery, the Germans fell back in the face of another combined tank-infantry attack. The Russians then shifted their assault and retook a smaller village near Klematina.

Running short of artillery shells (a problem the Russians never seemed to have), Hell put in a call to Materna, who sent 3,000 precious 105mm shells to the division’s Artillery Regiment 15. For the moment, the wall of divisional artillery fire could make up for deficiencies in the line, but Guderian had already taken two artillery regiments for his next move over Materna’s protests. Materna later said that the move was a “significant weakening of our defensive strength.”

The German positions along the Uzha River now came under attack. Losses on both sides were considerable, with the 15th losing 20 officers during the night of August 10-11. Dehmel’s 292nd, which had sent a reinforced combat group to another area, fell back from the hills south of Klematina in the face of heavy Russian attacks. As the situation grew more critical, part of the Reich was sent back to the front to help restore the situation.

Mid-August brought a new series of Russian attacks. Fortunately, they came mostly in battalion strength, but they struck at specific sectors of the thinly held German line and were supported by heavy artillery fire. The men occupying the foxholes and dugouts on the front line had little contact with anyone except their immediate neighbors on either side, and it was up to those small groups to fend off enemy attacks.

With the final exit of the Reich, the three divisions of Materna’s corps were stretched out in the rough, hilly region of the salient where, in most places, the enemy could approach to within 50-75 meters without being spotted. Hell’s 15th held a front of 22 kilometers, Straube’s 268th, 25 kilometers, and Dehmel’s 292nd had 14 kilometers to defend. The three divisions had already lost 97 officers and 2,157 NCOs and men after being in the salient for only one week.

To strengthen the salient, Guderian ordered General Hermann Geyer’s IX Army Corps (Bergmann’s 137th and Brig. Gen. Ernst Haeckel’s 263rd Infantry Divisions) into the northeast sector of the salient on August 15. Maj. Gen. Curt Gallenkamp’s 78th Infantry Division was also ordered to relieve the 15th on August 16 to give that beleaguered division some rest behind the lines.

In Berlin the generals at Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH, the German Army High Command) were taking a larger interest in Yelnya. Field Marshal Fedor von Bock was getting impatient as more German divisions became bogged down in the fighting with little to show for it. Guderian still wanted the salient held, and he lobbied the field marshal to remain steadfast, but von Bock had his doubts about hanging on. Indecisive for the moment, he let the battle continue.

On August 22, the command of the salient passed from Panzer Group 2 to Field Marshal Günther von Kluge’s 4th Army. At the time von Kluge was ill, so Guderian still had control of the area until he recovered.

The Yelnya salient resembled the head of a mushroom, with its stem only 22 kilometers wide. Stalin was determined to see it wiped out and was also getting impatient with the losses and lack of progress in obtaining that objective. Zhukov, who was still getting the divisions of his Reserve Army ready for battle, had been given orders to destroy the salient, but he would not act until he was ready, adding to Stalin’s frustration.

Meanwhile, Rakutin’s attacks increased, testing the German line. Haeckel’s 263rd felt the brunt of the blows. Located on the northeast sector of the salient, it guarded the northern flank of its “stem.” It was a particularly dangerous position, and the Russians knew it. They shelled the division throughout August 23 and launched an attack on a height known as Chimborasso. Although the attack was repulsed, the German division lost 150 men. Other strong attacks followed, and by the next day the average strength of the infantry companies was 30 to 40 men.

On the 25th the division lost another 200 men as the Soviets penetrated its line south of the village of Chuvashi. This time the division had nothing left to seal the breach. A counterattack that tried to recapture the lost positions cost Haeckel another 150 men.

Under pressure from both Geyer and Materna, the now recovered von Kluge visited the salient on August 27 to see for himself what their men were facing. He was appalled at what he encountered. In Haeckel’s sector, the 263rd had made another attempt to seal the breach in the Chuvashi area. This time it succeeded, but the division was worn out. Von Kluge immediately ordered Hell’s 15th to return to the line and relieve the 163rd.

While visiting Gallenkamp’s 78th, von Kluge was informed that the division had lost about 400 men in four days. Gallenkamp estimated that on average about 2,000 enemy artillery shells hit the division every day—most of them heavy caliber. He also stated that his division would be all but useless in a few days.

The other divisions in the salient basically gave the field marshal the same situation report. Returning to his headquarters, von Kluge contacted von Bock. He told his superior that, in his opinion, the salient should either be evacuated immediately or that the Moscow offensive should resume in the next few days to take pressure off the German units fighting there. Unfortunately, neither option was immediately possible.

Hitler, like Stalin, saw the battle at Yelnya as a matter of prestige and was not willing to give up the salient. Guderian, instead of resuming his Moscow offensive, was ordered to move his panzer group south to take part in another battle of encirclement—this time at Kiev.

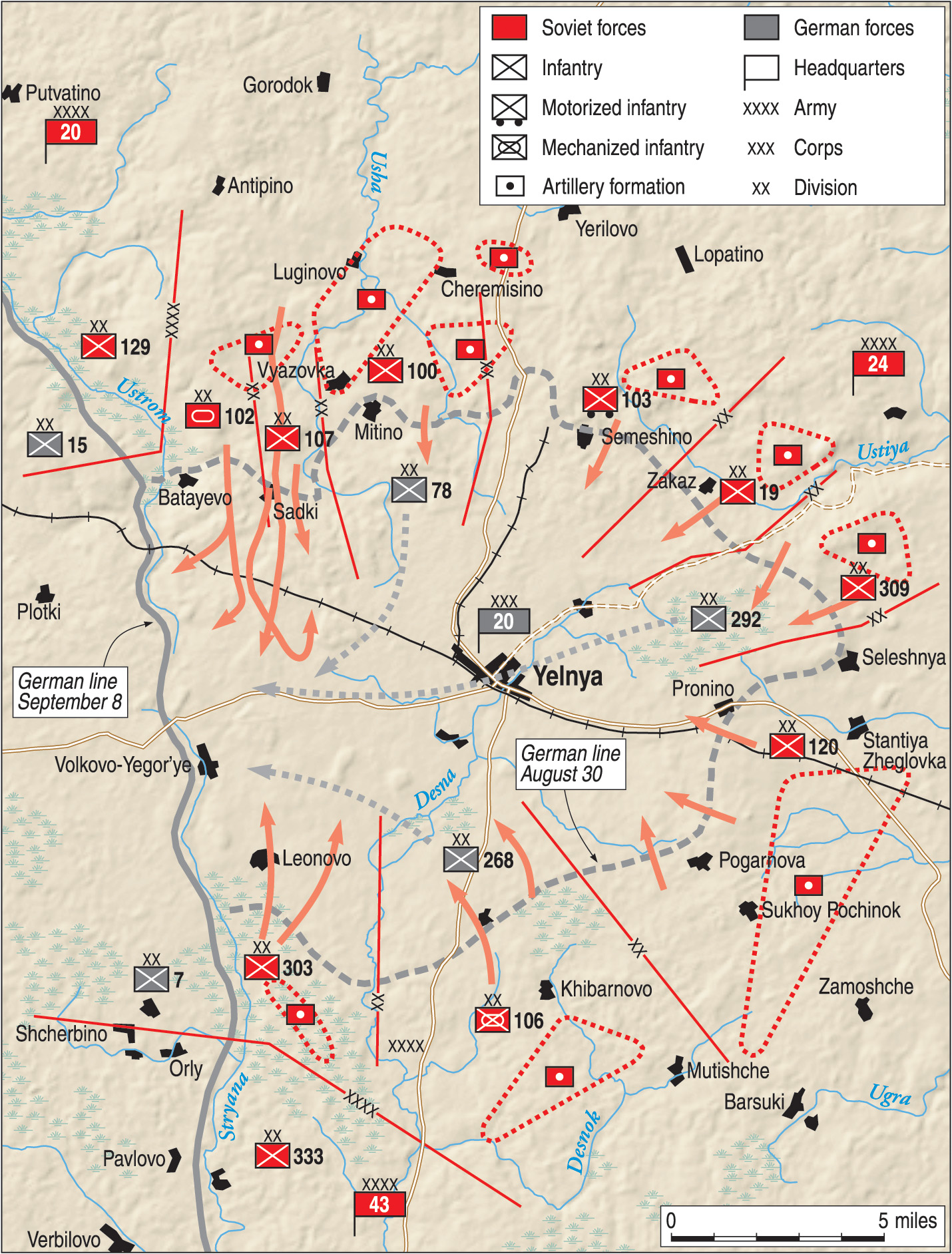

By August 30, Zhukov was ready. The Germans had become used to the violent battalion- and regiment-sized Soviet attacks that had hit them for the past weeks, but this time the attacks would take place on a divisional level with nine of 24th Army’s 13 divisions taking part. Although the Russians would be outnumbered 70,000 to 60,000, they had the advantage of being able to concentrate their forces while the Germans were strung along a 70-kilometer front. Rakutin had received replacements for his divisions, and Zhukov’s Reserve Army would provide more as the battle progressed.

With Zhukov in overall command, Rakutin ordered his artillery, which consisted of about 800 field pieces augmented by dozens of heavy mortars and some Katyushas, to open fire at 0730. Zhukov hoped to cut the stem of the salient with a pincer attack from the north and south. At the same time, two divisions would strike the eastern sector of the salient and drive toward Yelnya, splitting the German forces in two. As the thunderous barrage swept the German line, Zhukov gave the order to attack.

In the north, Russiianov’s 100th Rifle and Colonel Pavel Vasilevich Mironov’s 107th Rifle Divisions, supported by the 102nd Tank Division, struck the 137th on a four-kilometer front in the Sadki area, about 15 kilometers northwest of Yelnya. Soviet forces were able to penetrate the German line, and the tanks of the 102nd, supported by more infantry, widened the breach, pushing back the 483rd and 485th Regiments.

The southern sector of the stem, defended by the 268th, was hit by Aleksei Nikolaevich Pervushin’s 106th Motorized Rifle Division, supported by the 303rd Rifle Division. The attack took place on an eight-kilometer front in the Leonova area, some 16 kilometers southwest of Yelnya. With the greater width of the frontal attack, the Russians made slower progress. However, the Soviet artillery continued to cause rising losses among the German defenders.

On the 31st Zhukov pushed more tanks into the Sadki gap, allowing the Russians to advance another two kilometers. At the same time Russian infantry, supported by heavy artillery, slammed into Gallenkamp’s 78th north of Guryevo. The lead elements of the northern spearhead were now about six kilometers from Yelnya.

September 1 saw a continuation of the battle around Sadki. The southern attack around Leonova, although making little headway, prevented Materna from committing his meager reserves until he was certain where the main attack was coming.

At Sadki a regiment of Mironov’s 107th was able to move forward and cut the Yelnya-Smolensk rail line. The regiment was surrounded after a German counterattack, but it held out for three days until rescued by other Russian units.

Materna was almost ready to commit his reserves to the Sadki sector when a new crisis arose. Maj. Gen. Iakov Georgievich Koletnikov’s 19th Rifle Division, supported by the 309th Rifle Division, hit the junction of the 78th and 292nd Infantry Divisions, creating another gap in the line. With Maj. Gen. Konstantin Ivanovich Petrov’s 120th Rifle Division, which occupied positions south of the breakthrough, still uncommitted, Dehmel could not weaken other areas of his sector to help seal the breakthrough.

A meeting between von Bock, Halder, and Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, commander-in-chief of the Army, took place at Army Group Center’s headquarters on September 2. The consensus was that no one really knew when the Moscow offensive could be renewed. The best estimate would be late September, but it was only a guess. It was decided at the meeting that the Yelnya salient was serving no useful purpose and, with heavy fighting continuing there, it should be evacuated as soon as possible.

The withdrawal would be done in stages—something that the Germans became more and more adept at as the war went on. On September 4, service and supply personnel moved out undetected during the night. The following night, the divisions at the far eastern point of the salient retreated, covered by strong rear guards that fended off Soviet probing attacks. Heavy rain and fog masked the final stage of the withdrawal.

As the weather cleared, Rakutin attempted to catch the Germans, but it was too late. Soviet units entered Yelnya on September 6, but a new German defensive line several kilometers west of the town prevented any further advance. War correspondent Alexander Werth was allowed to visit the town a few days later. He described the scene in his book Russia at War: “Yelnya had been totally destroyed. On both sides of the road to the center of town, all the houses had been burned and all that was left was a pile of ashes and chimney stacks. The only building that still stood was a large stone church.”

The human cost at Yelnya was high on both sides. In his memoirs, Zhukhov estimated that the Germans sustained 45,000 to 47,000 killed or wounded, which is probably fairly accurate. The 24th Army, which bore the brunt of the fighting, suffered about 10,700 dead and 21,000 wounded of the 131,000 men committed to the battle from August 30 to September 9 alone.

With so little actual good news to report, the Soviet propaganda machine went into overdrive in reporting the victory at Yelnya. Press reports blew it all out of proportion, but there were some truths nestled in the writing. Although it was a minor battle compared to other actions in those first months of Barbarossa, it was the first real victory for the Red Army since the war began. It was also the first piece of Soviet territory wrested from the Wehrmacht.

The infantry divisions of the IX and XX Army Corps had been drained at Yelnya. Their depleted battalions would need several months to recoup, making them fairly ineffective once the drive for Moscow continued.

For conspicuous gallantry the elite status of Guards was introduced into the Red Army. On September 18th, Russiianov’s 100th and the 127th Rifle Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Timofei Gavrilovich Korneev and later by Colonel Andrian Zakharovich Akimenko, were reformed as the 1st and 2nd Guards Rifle Divisions for their performance at Yelnya. Mirinov’s 107th and Petrov’s 120th became the 5th and 6th Guards Rifle Divisions on September 26.

Although Yelnya became nothing more than a footnote in the history of the war on the Eastern Front, it showed what a determined Red Army could accomplish, even in the opening months of the war. For the men on both sides who fought and survived, it would be burned into their memories for the rest of their lives.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments